Asa Gray

Asa Gray (born November 18, 1810 in Paris , New York , † January 30, 1888 in Cambridge , Massachusetts ) was an American botanist . Its official botanical author's abbreviation is " A.Gray ".

Live and act

Youth and education

Asa Gray was born in Paris in the Sauquoit Valley, New York State , in 1810 . The family's ancestors were of Scottish-Irish descent and had come to the Sauquoit Valley from Massachusetts and Vermont. He was the eldest of the eight children of the married couple Moses Wiley and Roxana Howard Gray. His father was a farmer and also works as a tanner.

Like his siblings, Asa Gray was first homeschooled and then attended school in Sauquoit. At the age of twelve, he moved to high school in Clinton County, New York, and then attended Fairfield Academy in Fairfield, Herkimer County for four years .

His interest in science was sparked by teaching with James Hadley, a professor of medicine and chemistry at Fairfield Medical School, who also taught at Fairfield Academy. That's why Gray attended lectures at Fairfield Medical School again and again during his time at the Academy. At first he was mainly interested in mineral studies , but he only became aware of botany as his later field of activity in the winter of 1827/28 through the corresponding article in the Edinburgh Encyclopædia by David Brewster . After he had succeeded in identifying the first plants independently with the help of Amos Eaton's botanical handbook, he became an enthusiastic plant collector. He used the long summer vacation for botanical and mineralogical excursions to various areas of New York State.

His father recognized Asa's natural science talent and lack of interest in the profession of a farmer and enabled him to attend Fairfield Medical School from 1829. During his time as a medical student, Gray put on an extensive herbarium and a collection of minerals. Already during this time there was close contact with the doctor and botanist Lewis Caleb Beck from Albany and the botanist and chemist John Torrey from New York, who in turn introduced him to other botanists. In February 1831, he graduated from Medical School as a Doctor of Medicine, but never practiced as a doctor.

Professional background

After graduating from medical school, Gray initially taught chemistry, mineralogy, geology, and botany at Bartlett's High School in Utica . In June 1832 he gave his first botany lecture at Fairfield Medical School, shortly thereafter he gave seminars in botany and mineralogy at Hamilton College. The fees for his teaching activities enabled him to go on botanical excursions to Niagara Falls and other locations in the states of New York and New Jersey .

In the fall of 1833 he accepted John Torrey's offer to work as his assistant at the New York College of Physicians and Surgeons. Since Torrey was a professor of chemistry, Gray had to work in his chemical laboratory, but the real interest of the two scientists was botany. In 1834, Gray's first scientific publication appeared, dealing with mineralogy. His first purely botanical work was published in 1835 together with Torrey Monograph of the North American Species of Rhynchospora.

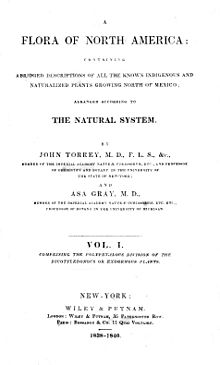

Torrey was only able to employ Gray as an assistant until the spring of 1834 because he lacked the necessary financial means. Gray therefore initially taught again at Bartlett's High School, with plans to return to New York at Torrey's chair after the summer break. Torrey had to refuse him again because he still lacked funding for an assistant position, but in 1836 gave him a position as curator and librarian at the Lyceum of Natural History . In his spare time he worked on his first textbook, the Elements of Botany , which he published in 1816. He also worked with Torrey on the Flora of North America. In the summer of 1836 he took a position as a botanist on the planned United States Exploring Expedition to the South Pacific under the direction of Charles Wilkes . Since the start of the expedition was delayed again and again, he used the time to do initial work on the botanical plant North American Flora, which Torrey had planned for a long time . When Wilkes' expedition finally left in 1838, Gray resigned from his position as a botanist and instead resumed a position as a research assistant with John Torreys in New York.

In 1838 he was appointed professor of botany at the newly founded State University of Michigan. Gray negotiated that he could spend an academic year abroad first before taking up the position. First, together with Torrey, he completed work on the Flora of North America , the first volume of which appeared in two parts in July and October 1838. In November he went on a trip to Europe to visit the important herbaria in which he wanted to study the extensive collections of American plants. He traveled to England, Scotland, France, Germany, Switzerland, Italy and Austria and studied, among other things, the herbaria in Padua, Berlin and Glasgow. On the trip he met some of Europe's leading botanists personally, including Archibald Menzies , Augustin de Saint-Hilaire , Robert Brown , William Jackson Hooker and Augustin-Pyrame de Candolle . He also made first contacts with numerous younger colleagues such as Alphonse Pyrame de Candolle , Joseph Dalton Hooker and Joseph Decaisne , which he maintained throughout his life.

In November 1839 he returned to America, but did not take up the professorship in Michigan because of disagreements with the university. Instead, he continued to work in New York at Torrey to publish the third and fourth parts of the first volume of the Flora of North America in June 1840 . The second volume was completed in 1843. The first part of the second volume appeared in May 1841 and the second in April 1842.

Work at Harvard

During a visit to Benjamin Daniel Greene (1793-1862) in Cambridge in 1843 , his father-in-law Josiah Quincy , President of Harvard College, Asa Gray offered the newly established Fisher Professorship in Natural History at Harvard. Gray agreed and took up the professorship that same year.

Gray had to build up the botanical department from the ground up; when he arrived Harvard had neither a botanical library nor a herbarium. The botanical garden was founded in 1805; the first director was the botany professor William Dandridge Peck. After his death in 1822, a new director could not be appointed for financial reasons, so that Thomas Nuttall, a lecturer in botany, was appointed as curator. He quit the position in 1833, since then the garden had only been looked after by a gardener, but no longer had a scientific director.

Gray moved into a small house in the botanical garden. After his arrival, Gray first set about building a library and laying out a herbarium. Although he received only a modest salary, he was able to build up an extensive literature collection within a short period of time, which he initially kept in his own house.

Since Gray feared that the herbarium and his library could be destroyed in a fire in his house, he offered to hand them over to Harvard University in 1864 if the latter agreed to build a separate building for it. The Harvard board of directors accepted the offer and had a small extension built on the house where Gray lived, a little later this was also expanded to include a small library. When it was handed over to the university in 1865, the library contained around 2,200 titles, the herbarium contained around 200,000 plant samples. By his death in 1888, Gray had nearly doubled the number of samples in the herbarium. It was the largest herbarium in the USA, and there were only a few larger herbaria in Europe.

Relationship with Charles Darwin

In contrast to his zoologist colleague at Harvard Louis Agassiz , Gray supported Charles Darwin's theory of evolution from the start , with whom he later became a lifelong friend. They first met in Kew ; they had introduced each other to Joseph Dalton Hooker . When Darwin read Alfred Russel Wallace 's thoughts on natural selection, he exchanged ideas with Gray about Wallace and his own ideas. Gray organized the first publication of Darwin's major work On the Origin of Species and administered its royalties in the United States. Darwin dedicated his book Forms of Flowers (1877) to Gray . Gray, however, was not a complete supporter of Darwin's theory of evolution, but rather saw the work of higher powers in nature in accordance with his religiosity .

Late life and death

After 30 years of activity, Gray withdrew from teaching and in the herbarium in 1873, but retained his professorship for botany. From then on he devoted himself even more intensively to the writing of botanical publications and began to work on a continuation of the Flora of Northern America . In doing so, he wanted to complete the work on the one hand, but also to update the thirty-year-old part on the other.

In October 1887 Gray returned from a trip to Europe, on which he had studied the herbaria of the Kew Gardens in London and the Lamarck Herbarium of the Jardin des Plantes in Paris. After his return he continued to work on the flora . From November 28, 1887, Gray suddenly suffered from paralysis and was only temporarily conscious in the weeks that followed. He died on January 30, 1888 and was buried on February 2, 1888 in Mount Auburn Cemetery , Massachusetts.

Honors

The plant genus Grayia Hook is named after Asa Gray . & Arn. from the Amaranth family (Amaranthaceae) and Asagraea Lindl. from the Germer family (Melanthiaceae).

In 1835 Gray was elected a member of the Leopoldina . In 1848 he was accepted into the American Philosophical Society . From 1855 he was a corresponding member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences and from 1862 of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Saint Petersburg . The Bavarian Academy of Sciences accepted him as a foreign member in 1859. In 1863 he was a founding member of the National Academy of Sciences . In 1868 he was elected a corresponding member of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences . In 1873 he was accepted as a foreign member of the Royal Society and in 1878 as a corresponding member of the Académie des Sciences . In 1879 he became an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh . The magazine Asa Gray Bulletin (1893-1901, 1952-1961) is named after him, as well as the Gray Herbarium and Grays Peak , a mountain in the US state of Colorado . Since 1984, the Asa Gray Award , the highest award of the American Society of Plant Taxonomists , has been given to deserving botanists.

In 2011, the US Postal Service issued a stamp with a portrait of Asa Gray as part of a series of stamps honoring Honorable Scientists. The stamp also shows the winter leaf ( Shortia galacifolia ). Gray discovered this plant, which occurs only in the states of North Carolina , South Carolina and Georgia , on his first trip to Europe in a herbarium in Paris and described it botanically together with Torrey. Gray had failed to find a living plant of this species for nearly 40 years. It was not until 1877 that a youth from North Carolina sent him a copy.

Fonts (selection)

A complete overview of Asa Gray's scientific publications can be found in the appendix to the American Journal of Science , volume 1888.

- Elements of botany. 1836

- A Natural System of Botany. , 1937

- with John Torrey: A Flora of North America . 2 volumes, Wiley & Putnam, New York 1838– [1843], (online) .

- Plantae Lindheimerianae: An Enumeration of the Plants collected in Texas, and distributed to Subscribers, by F. Lindheimer, with Remarks, and Descriptions of new Species, & c. In: Boston Journal of Natural History . Volume 5, 1845, pp. 210-264, (online) - with George Engelmann .

- Plantae Lindheimerianae, Part II. An Account of a Collection of Plants made by F. Lindheimer in the Western part of Texas, in the Years 1845-6, and 1847-8, with Critical remarks, Descriptions of new Species, & c. In: Boston Journal of Natural History . Volume 6, 1850, pp. 141-240, (online) .

- Contributions to North American Botany . In: Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences . Vol. 1-23, 1846-1888.

- with William Starling Sullivant : A Manual of the Botany of the Northern United States. James Munroe and Company, Boston 1848

- Genera florae Americae boreali-orientalis illustrata . 1848-1849.

- Plantae Fendlerianae Novi-Mexicanae: An Account of a Collection of Plants made chiefly in the Vicinity of Santa Fé, New Mexico, by Augustus Fendler; with Descriptions of the New Species, Critical Remarks, and Characters of other undescribed or little known Plants from surrounding Regions . Boston 1848, (online) .

- Plantae Wrightianae Texano-Neo-mexicanae: An account of a collection of plants made by Charles Wright . Smithsonian Institution, Washington 1852-1853, (online) .

- Botany of the United States Expedition during the years 1838–1842 under the command of Charles Wilkes , Phanerogamia , 1854

- Statistics of the Flora of the Northern United States. 1856

- First Lessons in Botany and Vegetable Physiology. Ivison and Phinney, New York 1857

- How Plants Grow: A Simple Introduction to Structural Botany. American Book Company, New York 1858

- Memoir on the Botany of Japan, in its relations to that of North America, and of other Parts of the Northern Temperate Zone. In: memoirs of the American Academy of Arts and Science. New series, VI, 1859

- Introduction to Structural and Systematic Botany and Vegetable Physiology. Phinney & Company, New York 1862

- How Plants Behave. Ivison, Blakeman, Taylor & Co., New York 1872

- Darwiniana: Essays and Reviews Pertaining to Darwinism. D. Appleton & Company, New York 1876 and 1889

- Synoptical Flora of North America. American Book Company, New York 1878–1897, completed by Benjamin Lincoln Robinson

- Gray's Botanical Text-book. volume I & II. American Book Company, New York 1879

- with Joseph Dalton Hooker: The Vegetation of the Rocky Mountain Region, and A Comparison With That of Other Parts of the World. In: Bulletin of the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories. United States Government Printing Office, Volume VI (1), Washington DC 1880, pp. 1-77

- Gray's School and Field Book of Botany. American Book Company, New York 1887

- Charles Sprague Sargent (Ed.): Scientific papers of Asa Gray . 2 volumes, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston / New York 1889 ( online) .

literature

- Jane Loring Gray (Ed.): Letters of Asa Gray . Houghton, Mifflin & Co., Boston / New York 1894, (online) .

- AH Dupree, Asa Gray 1810-1888 . Cambridge, Mass .: Belknap Press, 1959.

Web links

- Author entry and list of the described plant names for Asa Gray at the IPNI

- Literature by and about Asa Gray in the catalog of the Virtual Library of Biology (vifabio)

- Papers of Asa Gray, 1830–1953 (inclusive), 1830–1888 - Archives, Gray Herbarium Library, Harvard University Herbaria. With short bio and "A chronology of Gray's life"

- Asa Gray papers, 1840-1859 in the Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m W. G. Farlow: A Memoir of Asa Gray - Read before the National Academy, April 17, 1889 In: National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoirs (3) pp. 161-175, accessed June 18, 2016

- ↑ a b c d e f g Walter Deane: Asa Gray. In: Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club. Volume 15, No. 3 (March 2, 1888), pp. 59-72.

- ↑ Amos Eaton: A manual of botany for the northern states - comprising generic descriptions of all phenongamous and cryptogamous plants to the North of Virginia, hitherto described Webster and Skinners, Albany, Webster and Skinners 1817

- ↑ Asa Gray, JB Crawe: Sketch of the Mineralogy of a Portion of Jefferson and St. Lawrence Counties, NY In: American Journal of Science, 1834

- ^ Monograph of the North American Species of Cyperaceae. by John Torrey MD to which is appendend A Monograph of the North American Species of Rhynchospora. by Asa Gray, MD extracted from the Third Volume of the Annels of the Lyceum of Natural History, New York. George P. Scott & Cp. Printers, New York 1836

- ↑ David B. Williams, A Wrangle over Darwin, Harvard Magazine, 1998

- ↑ Letter 11330 -Darwin, C. to Gray, A. Jan. 21, 1878

- ^ The Darwin-Wallace Paper (complete) ( Memento from July 5, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Letter from Darwin to Gray - Comment 3 ( Memento of the original of July 28, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ David B. Williams, Harvard Magazine 1998

- ↑ Lotte Burkhardt: Directory of eponymous plant names . Extended Edition. Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin, Free University Berlin Berlin 2018. [1]

- ^ Member History: Asa Gray. American Philosophical Society, accessed August 27, 2018 .

- ^ Foreign members of the Russian Academy of Sciences since 1724. Asa Gray. Russian Academy of Sciences, accessed August 21, 2015 .

- ↑ Holger Krahnke: The members of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen 1751-2001 (= Treatises of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen, Philological-Historical Class. Volume 3, Vol. 246 = Treatises of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen, Mathematical-Physical Class. Episode 3, vol. 50). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2001, ISBN 3-525-82516-1 , p. 96.

- ^ Entry on Gray, Asa (1810 - 1888) in the archives of the Royal Society , London

- ^ List of members since 1666: Letter G. Académie des sciences, accessed on November 19, 2019 (French).

- ^ Fellows Directory. Biographical Index: Former RSE Fellows 1783–2002. (PDF) Royal Society of Edinburgh, accessed December 11, 2019 .

- ^ Alvin Powell: Gray gets stamp of approval - Postal Service honors Harvard's famed 'closet botanist. ' In: Harvard Gazette, June 30, 2011, accessed June 22, 2016

- ^ List of the Writings of Dr. Asa Gray - chronologically arranged. In: Appendix I. of the American Journal of Science. Third Series, Vol. XXXVI. - XXXXVI., No. 211-216, July-December 1888, James D. & Edward S. Dana, New Haven, pp. 1-42.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Gray, Asa |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American botanist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 18, 1810 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Paris , New York , USA |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 30, 1888 |

| Place of death | Cambridge , Massachusetts , USA |