Cochineal scale insect

| Cochineal scale insect | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

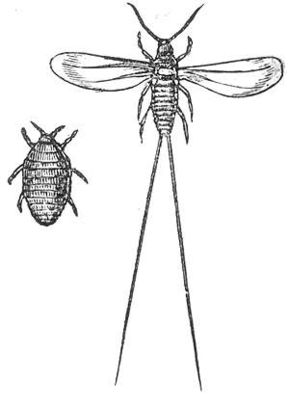

female (left) and male cochineal scale insects. |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Dactylopius coccus | ||||||||||||

| Costa , 1835 |

The cochineal scale , cochineal or cochineal ( Dactylopius coccus ) is a species of insect that is originally found in Central and South America as a pathogen on opuntia . The pigment carmine , the main component of which is carminic acid, is obtained from the female animals .

features

The females of the cochineal scale insect are wingless, broadly ovoid to round and about 6 to 7 mm long. Due to the high concentration of carminic acid, which is stored in the fat body and which is probably used to ward off predators and parasites, they appear dark purple. When crushed, they are bright red. The body is covered with white, floury wax , but the body is partially visible under the secretions. The males are hardly distinguishable from the females in the early nymph stages. In the penultimate stage they form dummy pupae in which they develop into two-winged adults . The eggs are pale red.

The cochineal scale insect differs from other species of the genus by the combination of the following features: The dorsal setae are thin and all roughly the same size. The five pore groups around the anal ring have only a few tracheal ducts , which are completely absent on the body. There are no thin pores on the belly side. The anal ring itself is only hardened in a thin area in the front area and has no setae. The posterior femurs have large, translucent pores and the antennae have seven limbs.

Way of life

Female cochineal whiteflies are only mobile in the first nymph stage . Like the adult phase, they spend a second nymph stage sessile on opuntia plants , with several generations forming common colonies . The host range includes the species Opuntia atropes , Opuntia cochenillifera , Opuntia ficus-indica , Opuntia hyptiacantha , Opuntia jaliscana , Opuntia megacantha , Opuntia pilifera and Opuntia tomentosa . After pupation, the flightable males spread and find the females via pheromones released by them . In contrast to most other scale insects, cochineal scale insects reproduce exclusively sexually . The males die shortly after mating. It is estimated that up to five generations are produced each year.

Important natural enemies of the species are a number of ladybird species , the gloss beetle Cybocephalus nigritulus , the aphid fly Leucopis bellula , the borer Laetilia coccidivora and Salambona intrusus, and the Taghaft Sympherobius amiculus .

distribution

In America the cochineal scale insect has a disjoint distribution area with a southern occurrence in Argentina and Peru and a northern occurrence in Mexico . Phylogenetic studies indicate that the animals came to Central America by sea trade, starting from their original occurrence in South America in pre-Columbian times. The species was also established by humans in the Canaries , Madagascar and South Africa .

Systematics

The cochineal scale was described as Coccus sativus by Lancry in 1791 , as Coccus maximus by Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck in 1801 and as Dactylopius coccus by Oronzio Gabriele Costa in 1835 . In the specialist literature, the species was falsely equated with the species Coccus cacti described by Carl von Linné in 1758 , which is now known as Protortonia cacti . The Latin name of the cochineal scale , which is valid today according to the International Rules for Zoological Nomenclature, is Dactylopius coccus , which was given preference over the older synonyms of Lancry and Lamarck due to its popularity. Phylogenetic analyzes indicate that the closest related species are Dactylopius zimmermanni and Dactylopius confertus , which are found in South America and live on cacti.

history

Use during the pre-Columbian period

It is not known when people in South America first used cochineal whiteflies to obtain red dye. The oldest textile remains that have been found so far, which have been dyed with cochineal shield insects, were found in a necropolis from pre-Christian times in Peru. This has led to speculation that ancient Peruvian cultures first discovered the use of this type of scale insect and that the technique became known from there in Central America. Other scientists argue that pre-Columbian Central American cultures were the discoverers of this dye or discovered it independently of the Peruvian cultures. The fact that predators of this scale louse species are common in Mexico, but relatively rare in Peru, speaks for an origin in Mexico. This suggests that the scale insect was originally only found in Mexico. Phylogenetic studies indicate that the animals came to Central America by sea trade, starting from their original occurrence in South America in pre-Columbian times.

Traditionally, the cultures in the southern highlands of Mexico, in what is now the Mexican state of Oaxaca , a very early development of the cochineal attitude. It developed domesticated lines of cochineal scale insect, which were more than twice as large as their wild cousins and many more carminic produced. While wild cochineal whiteflies thrived in locations over 2,500 meters above sea level, the domesticated lines are much more sensitive. They thrive best in the warm, dry climate of the southern Mexican highlands at temperatures between 10 and 30 degrees Celsius. Frost and premature summer rain can lead to the death of entire populations. Even with ideal climatic conditions, however, these domesticated lines had to be supplied with extensive care. During the summer rains, the farmers kept fertilized scale insects in a corner of their homes. Some also carried them in baskets lined with leaves to higher altitudes, where the summer months were drier.

The opuntia on which the scale insects were raised were also expensive to maintain. The preferred forage plant for cochineal whitefish was Opuntia ficus-indica , but other types of opuntia were also used. Each of the opuntia used were sensitive to frost and were susceptible to a range of plant diseases and pests. Since the scale insects grew best on young sprouts, the farmers regularly pruned the opuntia to encourage new growth. The farmers also created real opuntia plantations from cuttings. One and a half to three years after planting, the first scale insects could be applied to the young plants. In a labor-intensive process, the scale insects were then harvested from the opuntia. It was considered improper to touch the scale insects with your fingers. They were brushed by the Opuntia in wooden or clay bowls with sticks, feathers and small brushes. The lice were then dried. They were either spread out on mats and left in the sun for four or five days or dried in ovens. During the drying process, the scale insects lost about a third of their weight.

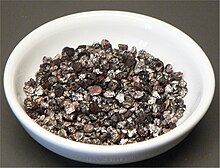

To extract the carminic acid , the animals are boiled, the dye is then precipitated , filtered and dried. About 70,000 animals are needed to make one pound of cochineal . A wide trade network already existed in pre-Columbian times for the trade in cochineal scale insects. Merchants from Nochixtlán traded in cochineal shield insects as far as what is now Nicaragua .

Some surviving documents from the beginning of the 16th century suggest that villages in the Oaxaca and Mixteca region paid over a hundred sacks of cochineal annually as tribute to the Aztec rulers. According to modern estimates, this would have corresponded to around nine tons of cochineal. Other villages paid their tribute in fabrics dyed with cochineal.

Similar to their European contemporaries, the Aztecs attached particular importance to the color red. The Aztecs associated red with sun, blood and death. There were several dyestuffs available to them for the production of red textiles, including plants that are similar to the European madder . The most intense red, however, could be produced with cochineal scale insects - similar to how the use of the Kermeslaus in Europe led to the most intense red tones. The use of the cochineal scale insect was very diverse. Mixed with vinegar, powdered cochineal lice were used to treat wounds. They were used to color dishes and women used it to color cheeks, necks, hands and breasts red. Carminic acid was also used to dye pots, baskets, statues, and even parts of houses red, and was one of the dyes Aztec scribes used to decorate their writings. The carminic acid obtained from the cochineal scale insects was of particular importance in the coloring of textiles and feathers that were used for Aztec clothing. The carminic acid obtained from scale insects had the greatest effect on animal fibers. Feathers and rabbit fur turned intensely red, while cotton fibers became a little more dull.

Use in modern times

It is not known how the Spanish King Charles V found out that the Spaniards encountered an intense red dye in South America. It is possible that he became aware of the codes and materials that the Spanish conquistadors sent to the Spanish royal court.

Red was one of the most valued colors in Europe; The high value assigned to textiles dyed in red was also due to the fact that it was still very difficult in the 16th century to dye textiles intensely red over the long term. The rarity of suitable dyes also contributed to this. Kermeslaus , which occurs mainly in Central Europe , is one of the starting materials for dyeing textiles red. The dyeing process was labor-intensive and time-consuming and required specific specialist knowledge, which dyers learned in a course lasting several years. However, not all dye guilds had this specific knowledge; Among the European dye guilds, those of Lucca and Venice in particular had a reputation for dyeing fabrics intensely and permanently red.

The Spanish conquistadors initially overlooked the commercial value associated with the cochineal scale. They made no effort to export dried cochineal whale to Europe. Some even refused to accept the cochineal deliveries that were offered to them as tribute payments. In the 1520s and 1530s, trade in cochineal scale insects remained almost entirely limited to the South American ethnic groups. The trade in cochineal required experience and market knowledge, which the conquistadors lacked. Spaniards who settled permanently in the new colonies grew plants such as wheat, sugar cane, wine, flax and the like or raised cattle and sheep, as they were familiar with from Europe. Hernán Cortés , whose estates were in the traditional cochineal area of Oaxaca, overlooked the commercial value of the cochineal scale insect and instead had his Mexican and African slaves dig for silver and grow sugar cane. From the mid-1530s, however, more and more Spanish merchants came to South America, who, unlike the conquistadors, recognized the business opportunities associated with the cochineal insects. From around the beginning of the 1540s, they began exporting cochineal to Europe in small quantities.

Cochineal in Europe

The Spaniards were the first Europeans to trade in the dye from the cochineal whale. In Segovia , Granada and Toledo at that time high-quality textiles were produced, but the market for this dye was limited. Later, dried cochineal whiteflies came mainly to Italy via trade.

The Tuscan Lapo da Diacceto was one of the first Italian dyers who worked with the cochineal dye in the early 1540s; he was assisted in his experiments by Cosimo I de 'Medici . In Venice, too, which dominated Europe in the trade in red dyes, people began to deal with the dye from 1543. In terms of color intensity, the cochineal dye was comparable with others - from scale insects such as Kermeslaus . However, compared to these, cochineal whiteflies contained fewer lipids , which made the coloring process easier. Cochineal was also much more productive than the coloring agents known in Europe up to now. Because of this, cochineal caught on very quickly as a dye and dyers in cities like Venice, Milan , Florence , Lucca and Antwerp , all known for their excellent fabrics, began working with cochineal as early as 1550. Markets where cochineal was regularly traded were not only established in the Spanish city of Seville by 1570, but also in Rouen , Lyon , Genoa , Nantes , Florence, Marseille and Antwerp, and cochineal was the most important export commodity from the Spanish colonies after silver in South America. The authorities of Seville estimated the value of cochineal exports at around 250,000 pesos annually, of which almost a quarter went to the state treasury as income.

Production in South America in the post-Columbian period

The breeding of cochineal scale insects remained predominantly in the hands of South American ethnic groups. The Tlaxcaltecs played a special role . During the conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards , the Tlaxcalteks entered into an alliance with Hernán Cortés and his conquistadors after initial resistance . They played a key role in the conquest of the Aztec capital Tenochtitlán , as they aided the Spaniards in reaching the Valley of Mexico and formed the main part of the attacking force. Due to this alliance with the Spanish crown during the conquest of Mexico, the Tlaxcaltecs enjoyed many privileges under Spanish colonial rule over other indigenous peoples , such as the permission to carry weapons, ride horses, hold nobility titles and largely autonomous administration of theirs Settlements. They dominated the cochineal trade until the 1570s. In the decades that followed, their Mixtec neighbors and the indigenous peoples in the Oaxaca valley began to breed cochineal fish again. In the early 17th century the center of cochineal production shifted to Oaxaca and towards the end of that century Oaxaca dominated the trade like a monopoly. The magnificent old town of Oaxaca de Juárez still testifies to the importance that the city gained during this period. In her history of the dye cochineal, Anne Butler Greenfield points out that the Spanish supremacy did not succeed in increasing cochineal production through coercive measures such as cultivation obligations. On the other hand, a futures market for cochineal insects was established as early as the end of the 16th century , with Spanish merchants and government employees granting loans to South American Indians , who repaid them with a previously fixed amount of cochineal. Accordingly, it was predominantly Spaniards who profited from the overseas business with cochineal insects. The willingness of South American Indians to sign these loan agreements and the large number of Indians who complained that they had received no or too little credit are a strong indication that the cultivation was also viewed by the Indians as economically attractive . Most of the cochineal bugs imported into Europe were used for dyeing textiles, and trade expanded to Southeast Asia as early as the 16th century. Similar to South and Central America, however, cochineal soon found use in cosmetics and in the course of the 17th century it was increasingly found on the color palettes of artists such as the Tintorettos , Jan Vermeer , Peter Paul Rubens and Diego Velázquez . The Spanish doctor Francisco Hernandez de Toledo recommended it in his De materia medica as a component of medicines.

It was Nicolas Hartsoeker who first published an enlarged illustration of a cochineal scale insect in Essai de dioptrique in 1694 . Ten years later, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek studied the scale insects responsible for color production very carefully and was thus able to finally clarify that it is not the opuntia but the insects that live on them that are necessary for the production of the dye. In 1776, Nicolas Joseph Thiéry de Ménonville traveled to Mexico on behalf of the French government to spy out the details of dye production. He succeeded in executing opuntia shoots with cochineal whiteflies, which he was able to reproduce successfully in Port-au-Prince in Haiti.

In addition to production in Mexico, the Spaniards also brought the cochineal scale to Guatemala , Honduras and the Canary Islands , while the English brought them to India and Africa. Attempts to breed the animals in Georgia and South Carolina were not very successful. From around 1860 the demand fell sharply due to the increasing availability of tar colors , in the 20th century the demand for cochineal as a non-toxic cosmetic or food color increased again. However, it can occasionally lead to allergic reactions . Today it is made in Peru, Mexico, the Canary Islands, Chile and Bolivia.

Cochineal whiteflies have also been used in Australia and Africa to control opuntia that have been dragged outside their natural range and appear as weeds.

Usage today

Carmine is relatively light and heat resistant. It is the most resistant to oxidation of all natural dyes and is even more stable than many synthetic dyes. Carmine with the E 120 label is approved as a food coloring . It is used for meat and sausage products, as well as for surimi , marinades, sauces, canned goods, cheese and other dairy products, pastries, glazes, pie fillings, jams, desserts, sweets, fruit juices, spirits and other beverages. The average consumer ingests one to two drops of carminic acid with their food each year. Carmine is also used as a cosmetic dye and for paints . The pharmaceutical industry uses it for oral dosage forms (dragees, film-coated tablets, capsules) and ointments.

Several cases of allergies to the dye have been documented, ranging from mild hives to anaphylactic shock . Carmine can cause asthma when inhaled. It is recommended by the Hyperactive Children's Support Group to avoid this dye in the diet of hyperactive children. A new regulation by the US Food and Drug Administration requires that from January 5, 2011, all foods and cosmetics that contain this dye are mentioned in the list of ingredients.

Food and other products containing carmine derived from scale insects are unacceptable to vegetarians and vegans . Many Muslims consider carmine-containing foods to be forbidden ( haram ) because the dye is obtained from insects. Many Jews also avoid foods that contain this additive. However, some Jewish authorities allow its use because the insect is dried and ground into powder.

Exhibitions

- 2017/2018: Rojo Mexicano. La grana Cochinilla en el arte . Palacio de Bellas Artes , Mexico City, DF, Mexico.

literature

- Amy Butler Greenfield: A Perfect Red - Empire, Espionage and the Qest for the Color of Desire . HarperCollins Publisher, New York 2004, ISBN 0-06-052275-5 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search).

- Helmut Schweppe: "Handbook of Natural Colorants", ecomed Verlagsgesellschaft, Landsberg, 1993, ISBN 3-609-65130-X

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Hans Strümpel, Willy Georg Kükenthal, Maximilian Fischer: Homoptera (plant teat) . Walter de Gruyter, 1983, ISBN 978-3-11-008856-4 , p. 81 .

- ↑ John L. Capinera: Encyclopedia of Entomology . 2nd Edition. Springer, 2008, ISBN 978-1-4020-6242-1 , pp. 2112 .

- ↑ a b Dactylopius coccus in "Scale Insects" (Systematic Entomology Laboratory, United States Department of Agriculture) ( Memento from June 17, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b c d e Yair Ben-Dov, Douglass R. Miller, Gary AP Gibson: A systematic catalog of eight scale insect families (Hemiptera: Coccoidea) of the world: Aclerdidae, Asterolecaniidae, Beesoniidae, Carayonemidae, Conchaspididae, Dactylopiidae, Kerriidae and Lecanodiaspididae . Elsevier, 2006, ISBN 978-0-444-52836-0 , pp. 215-218 .

- ↑ Luis C. Rodriguez, Eric H. Faundez, Hermann M. Niemeyer: Mate searching in the scale insect, Dactylopius coccus (Hemiptera: Coccoidea: Dactylopiidae) . In: European Journal of Entomology . tape 102 , 2005, pp. 305-306 (English, PDF ).

- ↑ a b c d Luis C. Rodriguez, Marco A. Mendez, Hermann M. Niemeyer: Direction of dispersal of cochineal (Dactylopius coccus. Costa) within the Americas . In: Antiquity . tape 75 , 2001, p. 73-77 (English, PDF ).

- ↑ a b c d e f g Amy Butler Greenfield: A Perfect Red - Empire, Espionage and the Qest for the Color of Desire . HarperCollins Publisher, New York 2004, ISBN 0-06-052275-5 , pp. 36 ff . (English).

- ↑ a b Rita J. Adrosko, Margaret Smith Furry: Natural dyes and home dyeing . Courier Dover Publications, 1971, ISBN 978-0-486-22688-0 , pp. 24-25 .

- ^ Amy Butler Greenfield, A Perfect Red - Empire, Espionage and the Qest for the Color of Desire . HarperCollins Publisher, New York 2004, ISBN 0-06-052275-5 , pp. 1–33 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ a b c d e f Amy Butler Greenfield: A Perfect Red - Empire, Espionage and the Qest for the Color of Desire . HarperCollins Publisher, New York 2004, ISBN 0-06-052275-5 , pp. 56 ff . (English).

- ^ Bernal Diaz Del Castillo: The Discovery and Conquest of Mexico 1517-1521 . Routledge Shorton , London, New York 1928, ISBN 0-415-34478-6 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Manuel Orozco y Berra, Historia antigua y de la conquista de México , 1880

- ^ A b c Amy Butler Greenfield: A Perfect Red - Empire, Espionage and the Qest for the Color of Desire . HarperCollins Publisher, New York 2004, ISBN 0-06-052275-5 , pp. 81 ff . (English).

- ^ A b Lucía E. Claps, María E. de Haro: Coccoidea (Insecta: Hemiptera) Associated With Cactaceae in Argentina . In: Journal of the Professional Association for Cactus Development . 2001, p. 77-83 (English, PDF ).

- ↑ John L. Capinera: Encyclopedia of Entomology . 2nd Edition. Springer, 2008, ISBN 978-1-4020-6242-1 , pp. 2112-2114 .

- ↑ a b Wild Flavors, Inc: [ E120 Cochineal ( Memento from October 22, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) E120 Cochineal] . In: The wild world of solutions . Retrieved July 19, 2005.

- ↑ COCHINEAL (also known as Carmine Red) ( Memento from July 31, 2012 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ Bug-Based Food Dye Should Be ... Exterminated, Says CSPI ~ Newsroom ~ News from CSPI . Cspinet.org. May 1, 2006. Retrieved November 13, 2009.

- ^ Joint FAO / WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA), Monograph for COCHINEAL EXTRACT, CARMINE, AND CARMINIC ACID , accessed December 8, 2014.

- ↑ Federal Register Vol. 74, No. 46 ( Memento June 6, 2011 in the Internet Archive ), FDA

- ↑ Pischei Teshuvah Yoreh Deah 87-20