Pawnee

The Pawnee (formerly also called Paneassa or Pani ) were a once militarily powerful Indian - tribe of the Central Plains , whose traditional settlement area - called Pâriru ' ("among the [in the middle of] the Pawnee") - along the tributaries since the end of the 15th century the Missouri River in Nebraska and northern Kansas . In the early 18th and early 19th centuries, they dominated trade along the Platte River , Loup River, and Republican Rivers on the Great Plains . As a semi-sedentary Plains Indians they operated arable farming along the river valleys of the prairie and supplemented this by seasonal hunting (especially on the Bison ), so they were part of the cultural area of the Prairies and Plains . They maintained particularly close contacts with the linguistically and culturally closely related powerful Arikara (Astárahi / Astaráhi) (also known as the "Northern Pawnee") in the north, who, together with the Sioux peoples of the Mandan and Hidatsa, dominated trade along the Upper Missouri River .

The Pawnee called themselves Cahriksicahriks / Cahiksicahiks ("Many Persons", sometimes rendered as "Men of Men" or "True Men"), reflecting both their population size and their power, and later called Paári . Their tribal name probably derives from Paahúkasa or Pákspasaasi ( "Osage haircut") from the name given to the popular among Pawnee warriors hairstyle that falsely as a mohawk or "haircut Mohawk" is known. Another version derives the tribal name from Paarika ("horn", but literally: "to be horned [mostly related to animals]") or Arika ("horn", the origin of the tribal name for the Arikara), which refers to the shape of their upright coiffed scalp lock .

Already weakened by diseases brought in by Europeans as well as military conflicts with the Apache and Comanche (Raaríhta sowie) as well as with the colonial powers, they later had to face the warlike Osage (Pasâsi '/ Pasâsi) advancing from the east and the numerically more powerful nomadic Lakota (Páhriksukat. Paahíksukat ) ("cut (s) the throat" - "cutthroat", "murderer"), Cheyenne (Sáhe / Sáhi) and Arapaho (Sáriʾitihka) ("dog meat eater") - collectively by the Pawnee as Cárarat ("hostile tribe") ) or Cahriksuupiíruʾ ("enemy") denotes a - to fight back who aggressively penetrated further and further into former Pawnee land. In addition, the feared Kiowa (Káʾiwa) and Plains Apache (Kátahka / Kátahkaʾ) (“foreign tribe living west of the Pawnee”) were among their bitter enemies. Due to the American Indian policy and the advancing frontier , tribes displaced westward (Delaware, Sauk, Fox, Kansa, etc.) also tried to find a new home - and if necessary by force. Around 1860 , the Pawnee population was reduced from around 12,000 to around 4,000. After repeated epidemics, a lack of harvests and wars, the Pawnee was estimated at around 2,400 people. A once established reservation along the Loup River in their tribal area, however, offered no protection against the ongoing raids of the Lakota (the Pawnee, however, were an easy target for robbery); therefore in 1873 they were forced to relocate to a new reservation in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma).

Many Pawnee warriors served as scouts in the U.S. Army during the wars against the Plains Indians (1865-1890) to track down and fight their traditional enemies who resisted the advance of the settler frontier on the Great Plains. In addition to the Apache Scouts and Crow Scouts, the Pawnee Scouts are the most famous Indian scouts .

Political organization

The chiefdom of the Pawnee, inherited through the female line, consisted of four bands (ákitaaruʾ) who spoke two mutually difficult to understand dialects : In the north, the centrally organized Skidi / Skiri federation spoke the so-called Skidi / Skiri dialect (SK dialect) (which was very similar to the language of the Arikara or Northern Pawnee) and the so-called South Bands dialect (SB dialect) was spoken by the three southern bands living further south , they did not form a central political unit, but consisted of three dominant bands (groups): the Chaui / Chawi, Kitkehakhi and Pitahawirata . Each of the four Pawnee bands was divided into several village groups that lived along the rivers. Although the Skidi / Skiri Federation was the most populous group of the Pawnee, the Chaui / Chawi of the southern bands were generally considered to be the politically leading group within the Pawnee, whose leading chief (reesaahkitáwiʾuʾ / riísaahkitawiʾuʾ) was generally considered to be outsiders (Indians and Europeans) Spokesman for all Pawnee bands appeared (but he had no political "power" to impose controversial issues or decisions on the other three bands). Disputes and violence between the four individual bands was not uncommon in history, especially between the Skidi / Skiri Federation (allies of the Arikara) and the Chaui / Chawi (Grand Pawnee) .

Skidi / Skiri Federation (from Ckirir / Tski'ki - "wolf" or Tskirirara - "wolf standing in the water", for example: "wolf people"), self-name Ckírihki Kuuruúriki ("people who resemble wolves, like Wolves behaves ”, based on the character and bravery of the animals, hence referred to by the French as Loup Pawnee and later by the Americans as Wolf Pawnee ), were among the southern bands also as Atatkipaasikasa (" Feces Lying In The Shade ", literally : "Excrement is in the shade") known

- Akapaxtsawa ('Tipi painted with a buffalo skull')

- Arikarariki ('Where there is an elk with small antlers')

- Arikararikutsu ( 'As where an elk with a large antler is')

- Kitkehaxpakuxtu ('Old Earth Village' or 'Old Earth Village')

- Tuhawukasa ('village that stretches over a hill')

- Tuhitspiat or Tuhricpiiʾat (SB dialect) ('village that spreads out into the plains')

- Tuhutsaku ('village within a ravine')

- Tukitskita ('village along an arm of the river')

- Turawiu (was just part of a village)

- Turikaku ('Central Village', 'Main Village')

- Tuwarakaku ('village within a dense forest')

- Tskisarikus ('Osprey')

- Tstikskaatit ('Black-Ear-of-Corn', i.e. 'Black Corn ')

Politically independent, but due to their dialect and their tribal areas, the following bands within the Pawnee were counted as part of the Skidi Federation:

- Tskirirara ('wolf standing in the water', were eponymous for the Skidi Federation)

- Páhukstaatuʾ (Sk dialect), Páhukstaatuʾ (SB dialect) or Pahukstatu ('Pumpkin-Vine-Village')

- Panismaha (also Panimaha , about 1770 this group split off from the Skidi, migrated south to the Texas-Arkansas border area, where they allied with the Taovayas / Tawehash (a tribe of the Wichita ), Tonkawa , Yojuanes and other Texan tribes first against Lipan Apache , then against the Comanche )

Southern bands - referred to by the Skidi / Skiri Federation as Tuhaáwit ("East Village People", i.e .: "People in the East")

- Cáwiiʾi (SB dialect), Cawií (Sk dialect), also: Tsawi , today mostly Chaui (official spelling of the Pawnee Nation) or Chawi (because of the location of their tribal area called "People in the Middle" - "people in the middle"; sometimes the name is also called "Those who beg for meat" reproduced), due to their political leadership by Europeans as Grand Pawnee referred

-

Kítkehahki (SB dialect), Kítkahaahki (Sk dialect), also: Kitkahaki or Kitkehaxki (literally: "Those who live in small earth huts" or "Those who live in small villages with muddy ground"), due to their dominance of the Middle Republican River as Republican Pawnee referred

- Kitkehahkisúraariksisuʾ (SB dialect) or Kítkahaahkisuraariksisuʾ (Sk dialect) (actually Kitkahahki Band, literally "true Kitkahahki" '; in the late 19th century, Kitkahahki split into two bands, this was the larger of the two)

- Kitkehahkiripacki (SB dialect) or Kítkahaahkiripacki (Sk dialect) (literally "Little Kitkahahki", a small splinter group that broke away from the main group in the late 19th century)

-

Piitahawiraata (SB dialect), Piítahaawìraata (Sk dialect), also: Pitahauirata , Pitahaureat , today mostly: Pitahawirata (official spelling of the Pawnee Nation) (literally: "Those who go downstream, ie to the east"), from the French also as Tapage Pawnee ("Screaming, howling Pawnee") and therefore later also called Noisy Pawnee ("Loud, noisy Pawnee") by the Americans (both foreign names are based on the translation of Piíta (SB dialect) and Piíta (Sk dialect) as "man, human" and Rata as "scream")

- Piitahawiraata or Piítahaawìraata (aka Pitahawirata, leading group)

- Kawaraakis (SB dialect), today mostly Kawarakis (possibly derived from the Arikara word Kawarusha - "horse" and the Pawnee word Kish - "people"), but the name could also come from the sacred bundle associated with this group called " Kawaraáʾa " , other Pawnee claimed that the Kawarakis spoke like the Arikara from the north , so they may have belonged to the Arikara who were expelled from their villages by the Lakota in 1794–1795 and then joined their Pawnee relatives in the south)

Traditional tribal area

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries (and before 1833) the four Pawnee Bands settled in clusters of settlements along major tributaries of the Missouri River (kícpaarukstiʾ / kicpaárukstiʾ) (literally: "holy water") in central and northern Nebraska Kansas. At the time of their first contact with the Europeans (Spaniards and later French), they formed one of the largest and best-known semi-sedentary prairie tribes with an estimated population of ten to twelve thousand people and dominated them militarily and politically for trade as well as for agriculture (later horse breeding and animal husbandry ) favorable region of the prairie (húraahkatuusuʾ / kuúhaaruʾ) ("flat land").

In the northwest and north lived the Skidi / Skiri Federation , historically also known as Loup Pawnee or Wolf Pawnee ; their tribal area stretched from the south bank of the Niobrara River (kíckatariʾ) (literally: "fast flowing water") south to the north bank of the Platte River (kíckatus / kíckatus) (literally: "shallow river"); their villages (once at least thirteen) were concentrated along the course of the Elkhorn River (kicita) and the many tributaries of the Loup River (ickariʾ / ickáriʾ) (literally: "[river where] many Indian potatoes [ grow] "), but since the early 19th century the Skidi / Skiri only lived in a village along the north bank of the Loup River.

South of them along both banks of the Platte River and south to both sides of the Republican River (with hunting grounds south to the Solomon River (kiicawiicaku) (literally: "Spring on the riverbank") and Smoky Hill River (aahkáwirarahkata) (literally: "yellow cliffs The three South Bands Pawnee lived in Kansas: the Kitkehahki (Republican Pawnee) in the west, the Chaui / Chawi (Grand Pawnee) in the center and the Pitahawirata (Tappage Pawnee / Noisy Pawnee) in the east.

The Kitkehahki Pawnee , historically mostly known as the Republican Pawnee , and their settlements dominated the central reaches of the Republican River named after them by the French , their tribal area was bordered in the north by the Platte River and in the south included the Prairie Dog Creek , a tributary of the Republican River in northern Kansas. Under pressure from the Kansa (árahuʾ / árahuʾ) , however, they had given up their original tribal area and had been resident along the Loup River since around 1811 to find protection from the Skidi / Skiri Federation .

The Chaui / Chawi Pawnee , called Grand Pawnee because of their political leadership role by the French (and later Americans) , settled in several villages south of the Platte River and on both sides of the Republican River; their tribal area was almost "central" between the Kitkehahki Pawnee living upstream (west) , the Pitahawirata (Tappage Pawnee / Noisy Pawnee) living downstream (east ) and the Skidi / Skiri Federation directly in the north. From the late 18th century, the Chaui / Chawi Pawnee moved into two large settlements south of the Platte River in order to be able to take military and organizational action against tribes advancing westward on their former tribal land (which, however, were themselves on the run from the advancing frontier).

The Pitahawirata Pawnee , historically also known as Tappage Pawnee or Noisy Pawnee , were the easternmost and at the same time smallest band of the Pawnee and lived in several villages south of the Platte River and on both sides of the Republican River. From the late 18th century they only inhabited a single settlement, which was mostly located near the Chaui / Chawi Pawnee ; In the middle of the 19th century they probably lived in a village together with the Chaui / Chawi Pawnee (since no separate name or location is given for a Pitahawirata settlement).

Culture

Each of these bands (groups) was divided into several village communities ( ituúruʾ - "village", or kítkahaaruʾ - "village made of earth huts"), which formed the basic social unit of the Pawneevolks. They lived in large, dome-shaped, earth-covered huts, but used the tipi (karacaape / káracapiʾ) (“skins draped from top to bottom”) for collective buffalo hunting (rahkátahuuruʾ) (“train on the high plains ”). The earth huts (ákaraarataaʾuʾ) of the Pawnee had an oval shape, were supported by a frame of 10–15 poles, which was covered with willow branches, earth and turf. At the apex of the hut there was an opening that served as a smoke outlet (called iriírasaakaratawi or iriíraacusaakaratawi) and a window. The floor of the hut was about 3 feet (about one meter) below the ground and the door (called íwatuuruʾ) could be locked by a bison skin at night. 30 to 50 people lived in large huts, a village had between 300 and 500 inhabitants and 10 to 15 households. Each hut was divided into a north and a south half or two sections, each led by a chief, and each section consisted of three families. Membership in a hut community was handled flexibly. When families returned from buffalo hunting in summer or winter, they could choose a new hut, although they usually stayed in the same village. The buffalo hunt was undertaken by the whole village community and the Pawnee left their permanent settlements during this time and lived in teepees; These several weeks of hunting expeditions on the plains west of the Pawnee territory were known as kataʾat ("to go on the hunt", but literally: "to undertake a campaign"), since the hunting grounds are in the tribal areas of the hostile nomadic Plains tribes (Comanche , Kiowa, Plains Apache, Cheyenne and Arapaho).

The women used mixed culture as a farming method . They cultivated the three main Indian crops (also known as three sisters ): several types of maize (ríkiisuʾ) (including preferably dark blue and mixed-colored maize varieties, but also red-colored hard maize ( kiceérit ) and yellow hard maize ( kiceeriktahkata ) as well as sweet corn (rikiistákarus / ríkistakarus) ) ), several types of squash (páhuks) and different types of beans (átit / atiik) (including garden bean (/ átiktariiʾus) , lima bean (átikatus) ), they also traded with neighboring tribes in order to obtain other coveted foods (e.g. B. special maize varieties: ríkiisastarahi / rikiisástarahi - "Arikara maize" and ríkispasaasi / rikiispasaasi - red-colored "Osage maize").

They were also very skilled in the art of pottery.

The Pawnee had a matrilineal culture, that is, parentage was defined by the mother. A young couple traditionally moved into the hut of the bride's parents ( matrilocality ). The woman-centered residence ( residence rule ) strengthened the close relationships between the wife, her sisters, her mother and their sisters ( aunts ), while the husband's family was not viewed as related. All relationships were related to only one maternal line; all sons married out ( exogamy ) and moved in with their future wives, daughters brought in husbands from other ethnic groups. Husbands remained part of their own families and therefore could not acquire any succession, property or inheritance rights within their wives' family.

Within the hut sections, the women were divided into three groups:

- married younger women who carried the brunt of the daily work,

- young, single women who got to know their job, and

- older women who were responsible for the upbringing and care of the young children.

Chiefs ( káhiiki / kahiíki or reesaáruʾ / riisaáruʾ ) of a band or a village group, priests and medicine men (kaahuúruʾ) ("powerful man") were favored by class differences, so the daughter of a chief was called Ctiisaáruʾ ("female chief") and the A chief's family can be traced back to a long lineage from previous chiefs. Each chief of a village or a band owned a sacred bundle (English: “Sacred bundle”, cuháriipiiruʾ or caátki called); so had z. B. the Kawarakis village group of the Pitahawirata Band a sacred bundle known as Kawaraáʾa , the Skidi / Skiri federation one called Cáhikspaaruksti „(" Holy Person "). Necromancers were given special powers against illness, enemy attacks and lack of food. Priests (kúrahus) were given the task of performing rituals and sacred chants. In addition to medicine man and hunting societies, the Pawnee also had warrior societies.

Before making a decision, each chief of a band always had to consult the tribal council ( kaawiitik or reesaarakaaruʾ / reesaaruʾ-rarahkaawi - “meeting, advising the chiefs”), consisting of several chiefs (called káhiiki / kahiíki or reesaáruʾ / riisaáruáʾ ), their advisers / assistants (. Sawaáruáhakuáh) called), war chiefs ( réhkita / ríhkita or raáwiirakuhkitawiʾuʾ ) , medicine men and priests convened, the meeting usually took place in the chief's house ( riisaárakaaru „-" house of the chief ").

Traditional religion

The ethnic religion of the Pawnee knew a great pantheon of natural deities. In particular, the stars in the sky - the morning star (warrior and god advisor), evening star (wife of morning star, fertility goddess of nature and women), sun, moon, black meteor star, red star, north star, wolf star (Sirius) and some Pawnee constellations - formed the highest gods and were implored in rituals for presence. They also used astronomy for practical things, such as determining the best time to plant corn. Mais was seen as the symbolic mother (of Atira , the wife of Tirawahat) through whom the sun god showed his grace.

An exception for the North American tribal religions is the pronounced high god figure Tirawahat (“the vast expanse”), who functioned as the creator god and as a personified but unrecognizable “our father above”. It did not intervene in people's everyday life and manifested itself in 16 manifestations (e.g. wind, clouds, light, storm, rain, etc.). His omnipotence was worshiped, but other gods were considered much closer to humans. In addition to the gods of the sky, the Pawnee also believed in other gods of nature such as water monsters and mother cedar (gods of "biology") or grebes and bears (gods of "medicine")

The morning star ritual

Until the 1840s there was an in Skidi human sacrifice - ritual , which was dedicated to the morning star. The victim was usually a virgin girl captured by another tribe. At first the girl was treated well and an elaborate scaffold was built for the sacrifice. Before the morning star rose on the day of the sacrifice, the girl was led onto the scaffold. When the star appeared on the horizon, medicine men opened the girl's chest and pierced the body with arrows. In her book The Lost Universe, author Gene Weltfish describes how a young Lakota Indian was captured and killed by the Pawnee. It is believed that it was the last human sacrifice of the Pawnees, whose cruel ritual is said to have descended from the Aztecs in Mexico .

history

Battle against Apaches and Spaniards (approx. 1650 – approx. 1740)

Francisco Vásquez de Coronado visited the neighboring Wichita in 1541 and met a Pawnee chief from the village of Harahey. During the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries mounted Plains Apaches ( Jicarilla , Lipan , Mescalero ) and Navajo ( Diné ) began raiding and robbing villages of the Pawnee, Wichita, and the Caddo . They burned down the villages, killed as many warriors as possible and dragged the children and women into slavery. The Apaches and Navajo sold their slaves to the Spanish and Pueblo Indians in New Mexico and to the French in the east. The slave trade became so lively that the name Pawnee became a synonym for slave in the 17th and 18th centuries . These Apache raids and slave hunts (and the French and Spanish slave market) forced the Pawnee (as well as the Wichita and Caddo) to abandon their once sprawling and open villages and to establish centralized, palisade and guarded settlements. In 1720 the Pawnee defeated the expedition of Pedro de Villasur , who tried to keep the Pawnee away from French traders and their influence with 40 Spanish soldiers and 20 Pueblo warriors, and was killed in the process. The Pawnee had recently begun to trade with the French, and from 1750 onwards they won them as their allies against their enemies. With the help of French weapons and ammunition, the Pawnee were now able to defend themselves against the incessant raids and slaves of the Apaches .

Alliance with the French and Comanche, displacement of the Apaches from the Plains (approx. 1740 – approx. 1775)

In 1746, the Pawnee also served as an intermediary between the Comanches and the French, which enabled their traders to penetrate into Spanish territory to Santa Fe and to supply the Comanche with rifles and ammunition. This enabled the already mounted Comanche (together with their allies, the Wichita, Tonkawa , Caddo and groups of the Pawnee) to successfully wage war against the Apaches, who were also mounted but did not have rifles, and finally to the mountains of New Mexico and Mexico as well as in to displace the outskirts of the Southern Plains in southern Texas.

With the appearance of the Comanche on the Great Plains and their warlike incursions into the eastern Apacheria , the Comanche came into possession of large herds of horses through robbery and trade; they also developed into the first successful horse breeders and the best riders among the Plains Indians . Soon the Comanche possessed a surplus of horses of approx. 90,000 to 120,000 animals, brokered the horses by trade and barter north to tribes such as the Crow and were considered far and wide to be the horse-richest tribe on the plains. This inevitably led to frequent conflicts, since the Pawnee, Kansa and Osage, poor on horses, armed with French rifles , often simply shot their trading partners and took the horses with them instead of conducting lengthy negotiations. While the Pawnee and Osage now owned horses (mostly stolen Comanche horses), the conflict escalated in 1746 in a great war between the Pawnee and Comanche. After the main fighting was over, the Pawnee, as already mentioned, even acted as mediators between the French and the Comanche. In 1750 the Wichita forged peace between Pawnee and Comanche, and the following year the now allied tribes jointly defeated their enemy, the Osage.

Horse raids against Comanche (from approx. 1780) and wars against Osage (from approx. 1750)

Although many Comanche had moved to the area south of the Arkansas River in 1750 , the Yaparuhka and Jupe stayed north of the river, fighting Lakota and Cheyenne in the Black Hills until 1775, and robbing the Arikara villages along the Missouri (until 1805 was the North Platte River , the northern headwaters of the Platte River, also known as the Padouca / Comanche Fork). The peace between Pawnee and Comanche did not last, and the Pawnee traveled great distances to steal the horses of the Comanche, Kiowa, and Kiowa Apaches (and occasionally the Apaches) in New Mexico and Texas . Usually 10 to 30 warriors set out on foot to robbery and, if successful, returned mounted and with scalps, goods and prisoners. Because of this tactic, the mounted Kiowa contemptuously called the Pawnee and Osage hikers or walkers . This in turn led to fierce clashes and fighting (1790–1793 and 1803).

Despite being defeated by the Pawnee-Comanche Alliance in 1751, the Osage expanded and expanded their tribal territory significantly north, west and south at the expense of the Pawnee and Comanche. The Pawnee therefore left their territories in Kansas despite their victory and moved north to the Platte Valley in Nebraska, the Comanche oriented themselves further west and south. In addition, the Pawnee suffered from the attacks of the British armed Sioux (Lakota, Nakota ) and Osage, since the French gave up Louisiana in the Peace of Paris in 1763 and the Pawnee thus lost their most important allies and arms suppliers.

Conflicts with Plains tribes, loss of dominance (from approx. 1790 - approx. 1879)

Already severely weakened by several epidemics and by the constant wars against Blackfoot , Lakota, Comanche, Osage, etc. a. decimated, the Pawnee could no longer maintain their power and got more and more on the defensive. If by 1720 they were still the dominant tribe in Nebraska and Kansas, now their enemies had gained the upper hand. As a result, several groups of the Pawnee migrated south and joined their already severely decimated Wichita relatives along the Red River . When about 300 northern Pawnees settled with the Wichita after a trade visit in 1771, they mixed with the Wichita and became known as Asidahesh .

The departure of the Pawnee and Comanche from the Central Plains suddenly created a power vacuum into which pillaging raiders of the Cheyenne and Arapaho advanced. They successfully asserted themselves against all the tribes that still lay claim to the area (Comanche, Kiowa, Kiowa-Apaches, Pawnee and Ute ), became the most important traders on the plains and, from 1840, allies of the Comanche and Kiowa. The Pawnee, however, had to suffer from constant raids and horse thefts of the allied tribes until the defeat of the Arapaho and Cheyenne by the Americans in 1877–1879 .

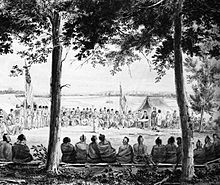

Assignment of the tribal areas and move to the reservation (1818-1892)

In 1795 a group of Pawnee and Wichita in San Antonio reported to the Spaniards the insults and injustices they had received from the Americans and showed an interest in strengthening friendship with the Spaniards. Despite the interest on the part of the Spaniards, the meeting did not result in an alliance. Later a delegation of tribal chiefs visited President Thomas Jefferson , and in 1806 Lieutenant Zebulon Pike , Major GC Sibley, and Major SH Long came to the Pawnee villages. In several treaties, the Pawnee ceded their land to the United States between 1818 and 1892 and moved to a reservation on the Loup River in Nebraska. Permanent raids by the Lakota from the north culminated in a massacre on August 5, 1873. The Massacre Canyon Monument was built in 1930 to commemorate him . In addition, the penetration of white settlers from the east and south in 1875 forced them to leave their reservation and move to the Indian territory. Many young Pawnee preferred to join the U.S. Army Cavalry as scouts rather than endure the desolation of reservation life.

In the 20th century, most Pawnee turned to Christianity. However, there are still followers of the traditional religion, many practice both side by side, some profess the peyote religion .

Demographics

In the 19th century, the Pawnee were from smallpox and cholera - epidemic almost wiped out. Their population was reduced to an estimated 600 tribe members in 1900. At the 2000 census, there were 2,486 Pawnee living on or near their Oklahoma reservation. In 1996 only four older Pawnee spoke their traditional language. In 1964, the Pawnee received a back payment of $ 7,316,096.55 for undervalued land sales from the previous century. Today the Pawnee strive to revive their ancient culture and meet their Wichita relatives twice a year .

Designations

The counties of Pawnee County in Kansas, Pawnee County in Nebraska, and Pawnee County in Oklahoma are named after the tribe.

See also

List of North American Indian tribes

literature

- John R. Swanton: The Indian Tribes of North America . Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 145, Smithsonian Press, Washington DC, 1969, ISBN 0-87474-092-4

- Raymond J. DeMallie: Handbook of North American Indians . Volume 13: Plains. Smithsonian Institution (Ed.), Washington, 2001, ISBN 0-16-050400-7

- Gene Weltfish: The Lost Universe - Pawnee Life and Culture . University of Nebraska Press, 1990, ISBN 978-0-8032-5871-6

Web links

- Homepage of the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma

- Pawnee Indian Tribe

- Pawnee Indian History in Kansas

- Pawnee Indians

Individual evidence

- ^ Barry M. Pritzker: A Native American Encyclopedia, History, Culture and Peoples. Oxford Univ. Press, 2000, ISBN 0-19-513877-5 . P. 351.

- ^ Gene Weltfish: The Lost Universe, Pawnee Life and Culture , p. 5, University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 0-8032-5871-2

- ^ Gene Weltfish: The Lost Universe: Pawnee Life and Culture , p. 463

- ↑ Nicknames were common among Indians, especially between neighboring groups - be they related or not, allied or enemies - these terms often had a derogatory or friendly, funny reference to special behavior or appearance

- ^ Georg E. Hyde, Savoie Lottinville: The Pawnee Indians , University of Oklahoma Press, 2007, p. 361, ISBN 978-0806120942

- ↑ a b Christian F. Feest : Animated Worlds - The Religions of the Indians of North America. In: Small Library of Religions , Vol. 9, Herder, Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 1998, ISBN 3-451-23849-7 . Pp. 90-92.

- ↑ Steven Charleston et al. Elaine A. Robinson (Ed.): Coming Full Circle: Constructing Native Christian Theology. Augsburg Fortress Publishers, Minneapolis (USA) 2015, ISBN 978-1-4514-8798-5 . P. 32.

- ^ Gene Weltfish (1965): The lost universe: Pawnee life and culture. New York: Basic Books, pp. 448–462 (preview at google books)

- ↑ a b Handbook of Texas Online - The Pawnee Indians

- ^ Gene Weltfish: The Lost Universe: Pawnee Life and Culture , p. 471

- ^ Anna Lee Walters: The Pawnee Nation. Capstone, Mankato (USA) 2000, ISBN 0-7368-0501-X . P. 17.