Diego Rivera

Diego María de la Concepción Juan Nepomuceno Estanislao de la Rivera y Barrientos Acosta y Rodríguez (born December 8 or December 13, 1886 in Guanajuato , † November 24, 1957 in Mexico City ) was a Mexican painter . Alongside David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco, he is considered the most important modern painter in Mexico. Together they were known as Los Tres Grandes (The Big Three) .

Diego Rivera worked in Europe from 1907 to 1921, and in the United States in the early and late 1930s. In his panel paintings Rivera adapted many different styles in quick succession and occupied himself with Cubism for a long time . During his time in Europe he was in contact with leading representatives of modern art such as Picasso , Braque and Gris . After his return to Mexico, Diego Rivera mainly worked on his large mural projects, which he painted in the Palacio Nacional , the Palacio de Bellas Artes , the Secretaría de Educación Pública and in various institutions in the United States. These murals , which he understood as a contribution to popular education, contributed to a large extent to Rivera's fame and success. The other facets of his oeuvre took a back seat behind them.

The exact number of his panel paintings is not known, so far unknown oil paintings by Rivera are still being found. Many of them were portraits and self-portraits, a large number also showed Mexican motifs. The latter, as well as variations of his murals motifs, were particularly popular with American tourists. In addition, Rivera made drawings and illustrations and designed costumes and sets for a theater production. These aspects of his oeuvre have not yet been dealt with in detail in the Rivera literature.

Rivera joined the Communist Party of Mexico in 1922 and served on its executive committee for a while. In 1927 he traveled to the Soviet Union on the occasion of the anniversary of the October Revolution and wanted to contribute to artistic development there; because of his criticism of Stalinist politics, however, he was advised to return to Mexico. Due to his critical position on Josef Stalin and the government contracts accepted by Rivera, the Communist Party of Mexico excluded him in 1929, but in 1954 accepted one of his requests for resumption.

In the 1930s Rivera turned to the ideas of Trotskyism . He campaigned for Leon Trotsky to be exiled in Mexico and temporarily sheltered him in his home. After political and personal conflicts with Trotsky, the Mexican artist broke off ties in 1939. Diego Rivera's political convictions are also reflected in his works, in which he propagated communist ideas and immortalized leading figures of socialism and communism. In connection with his political activities, Rivera also published articles and was involved in the editing of left-wing magazines. Rivera married the artist Frida Kahlo in 1929 , who shared his political convictions.

Life

childhood and education

Diego Rivera and his twin brother José Carlos María were born in Guanajuato on December 8th or 13th, 1886 as the first sons of the teacher couple María del Pilar Barrientos and Diego Rivera . The family background of Diego Rivera remains uncertain, as it is mostly rumored by himself. The paternal grandfather, Don Anastasio de Rivera, was born there as the son of the great-grandfather of Italian origin, who was in the Spanish diplomatic service in Russia, and the unknown Russian mother died in childbirth. Don Anastasio later emigrated to Mexico, bought a silver mine and married Ynez Acosta. Allegedly he fought for Benito Juárez against the French intervention . The maternal grandmother, nemesis Rodriguez Valpuesta, is said to have been of half-Indian descent. With his non-verifiable statements, Rivera contributed to the creation of legends about his person and located himself in the history of Mexico, which is a central aspect of his overall work.

Diego Rivera's twin brother died in 1888; his mother gave birth to a daughter named María in 1891. The left-leaning articles of the father, author and co-editor of the liberal magazine El Demócrata , so outraged his colleagues and the conservative part of the readers that even his family was attacked. After he had speculated in the mining business, they moved to Mexico City in 1892 , where Diego sen. got a job in the civil service. However, the father took care of the son's education from an early age: Diego junior had already learned to read at the age of four. From 1894 he attended the Colegio Católico Carpantier . His drawing talent was encouraged from the third grade onwards through additional evening courses at the Academia de San Carlos . In 1898 he enrolled there as a regular student after receiving a scholarship.

As a result, Diego Rivera came into contact with very different conceptions of art. He mentions Félix Parra , José María Velasco and Santiago Rebull as his main teachers at the Academy (in that order) . Rebull, who recognized the boy's talent and may have preferred him to the annoyance of his fellow students, was a student of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and a supporter of the Nazarenes , while Parra was a naturalist with an interest in pre-Hispanic Mexico. The course followed the European model with technical training, rational research and positivistic ideals.

Rivera worked both in the studio and in the landscape, orienting himself strongly on Velasco, from whose perspective teaching he benefited. He followed his teacher especially in depicting the special colors of a typical Mexican landscape. In addition, Rivera met the landscape painter Gerardo Murillo at the academy , who had recently been to Europe. Murillo influenced the art student through his appreciation of Native American art and Mexican culture, which came to fruition in Rivera's later work. In addition, Murillo Rivera taught about contemporary art in Europe, which made him want to travel to Europe himself.

In his autobiography Rivera expresses admiration for José Guadalupe Posada , whom he got to know and appreciate at this time. In 1905 he left the academy. In 1906 he exhibited 26 of his works for the first time, mostly landscapes and portraits, at the Academia de San Carlos' annual art exhibition organized by Murillo and was also able to sell his first works.

First stay in Europe

In January 1907, Diego Rivera was able to travel to Spain thanks to a scholarship from Teodoro A. Dehesa , the governor of the state of Veracruz , and his reserves from the sales. On the recommendation of Murillo, he joined the workshop of Eduardo Chicharro y Agüeras , one of the leading Spanish realists . The painter also advised Rivera to travel through Spain in 1907 and 1908 to get to know different influences and currents. In the years that followed, Rivera tried different styles in his works. In the Museo del Prado he copied and studied paintings by El Greco , Francisco de Goya , Diego Velázquez and Flemish painters. Rivera was introduced to the Spanish avant-garde in Madrid by the Dadaist writer and critic Ramón Gómez de la Serna . In 1908 Rivera also exhibited in the second exhibition of Chicharro students.

Encouraged by his avant-garde friends, Rivera traveled on to France in 1909 and attended museums, exhibitions and lectures. He also worked in the schools of Montparnasse and on the banks of the Seine . In the summer of 1909 he traveled on to Brussels. Here he met the Russian painter Angelina Beloff , who was six years his senior . She became his first partner and accompanied him to London. There he studied the works of William Hogarth , William Blakes and William Turner . At the end of the year, Rivera, accompanied by Beloff, returned to Paris and in 1910 presented works for the first time in an exhibition of the Société des Artistes Indépendants . As his scholarship expired, Rivera returned to Mexico via Madrid in the middle of the year, where he arrived in August 1910.

In November he showed some of his works at the Academia de San Carlos as part of an art exhibition on the occasion of the centenary of Mexico's independence . During his stay the Mexican Revolution broke out. No evidence can be found for the assertion, made by Rivera himself, that he fought at the side of Emiliano Zapata at the beginning of the revolution , so that it is very likely a legend that emerged later. Despite the political turmoil, the exhibition for Rivera was an artistic and financial success, seven of the paintings were purchased by the Mexican government. With the proceeds he was able to return to Europe in June 1911.

Second stay in Europe

In June 1911 Diego Rivera returned to Paris, where he moved into an apartment with Angelina Beloff. In the spring of 1912 the two drove to Castile . During a stay in Toledo , Rivera met several Latin American artists living in Europe. He had particularly close contact with his compatriot Angel Zárraga . In Spain Rivera experimented with pointillism . After their return to Paris in the autumn of 1912, he and Angelina Beloff moved to the Rue du Départ. The artists Piet Mondrian , Lodewijk Schelfhout and the painter Conrad Kickert - at the time a correspondent for the Dutch weekly magazine De Groene Amsterdammer - whose work was influenced by Paul Cézanne , lived in the neighborhood . At this time, the first Cubist influences made themselves felt in Rivera's painting . He developed his own understanding of Cubism, which was more colorful with him than with other Cubists. After he became friends with Juan Gris in 1914 , his works also showed influences from the work of the Spaniard.

In 1913 he exhibited his first cubist paintings in the Salon d'Automne . In that year he also took part in group exhibitions in Munich and Vienna, and in 1914 in Prague, Amsterdam and Brussels. At that time, Diego Rivera was very actively involved in the theoretical discussions of the Cubists. One of his most important interlocutors was Pablo Picasso . In April 1914, the Berthe Weill gallery organized Rivera's first solo exhibition, in which 25 of his Cubist works were shown. He was able to sell some of the works, so that his financial situation improved. This enabled Rivera and Beloff to travel to Mallorca with other artists in July , where Rivera learned of the outbreak of the First World War . Due to the war, her stay on the island lasted longer than planned. They traveled on to Madrid via Barcelona, where Rivera met various Spanish and Latin American intellectuals. There he took part in 1915 in the exhibition Los pintores íntegris organized by Gómez de la Serna , in which Cubist works were exhibited for the first time in Spain and sparked heated discussions.

In the summer of 1915, Rivera returned to Paris, where his mother visited him. From her and the Mexican intellectuals in Spain he received information about the political and social situation in his home country. Rivera followed the development of the revolution in his home country with benevolence and also addressed this in his work. In 1915 Rivera began an affair with the Russian artist Marevna Vorobev-Stebelska , which lasted until his return to Mexico. With his painting he achieved increasing success. In 1916, Diego Rivera participated in two group exhibitions of Post-Impressionist and Cubist art at Marius de Zayas' Modern Gallery in New York . In October of that year he had the solo exhibition Exhibition of Paintings by Diego M. Rivera and Mexican Pre-Conquest Art there . In addition, his first son named Diego was born this year from the relationship with Angelina Beloff.

In 1917 the director of the Galerie L'Effort moderne, Léonce Rosenberg , signed Diego Rivera for two years. He was introduced by Angelina Beloff to a discussion group organized by Henri Matisse for artists and Russian emigrants and took part in the metaphysical discussions there. These influenced Rivera's work through a more unadorned style and simplified compositions. In the spring, Rivera came into conflict with the art critic Pierre Reverdy , who had risen to become one of the leading theorists of Cubism and who had badly discussed Diego Rivera's works. There was a fight between the two of them. As a result, Diego Rivera turned away from Cubism and returned to figurative painting. He also broke with Rosenberg and Picasso, which led to Braque, Gris, Léger and his friends Jacques Lipchitz and Gino Severini also turning away from him. In the winter of 1917 his first son died of complications from the flu.

Together with Angelina Beloff, Rivera moved into an apartment near the Champ de Mars in 1918 . The influence of Cézanne was noticeable in his paintings, in some still lifes and portraits also that of Ingres. Rivera took up Fauvist elements, as well as the style and color scheme of Renoir. This return to figurative painting found the support of the art writer Élie Faure , in whose exhibition Les Constructeurs the Mexican painter had already participated in 1917. Faure had a great influence on Rivera's further development because he was interested in the art of the Italian Renaissance and discussed with him about the social status of art. As a result, Diego Rivera considered wall painting as a form of representation.

Diego Rivera first met David Alfaro Siqueiros in 1919 . Together they discussed necessary changes in Mexican art. They shared common views on the task of a Mexican art and the place it should have in society. On November 13th, Rivera's lover Vorobev-Stebelska gave birth to his daughter Marika . Rivera painted two portraits of the Mexican ambassador in Paris and his wife. The ambassador spoke to José Vasconcelos , the new university director in Mexico City, for Diego Rivera and asked that the painter finance a study visit to Italy. This scholarship enabled Diego Rivera to travel to Italy in February 1920. During the following 17 months he studied Etruscan , Byzantine and Renaissance works of art there. He made sketches of the Italian landscape and architecture as well as the masterpieces of Italian art. Most of them are missing.

Rivera studied Giotto's frescoes and Michelangelo's wall and ceiling paintings in the Sistine Chapel . So Rivera got to know the fresco technique and the expressive possibilities of monumental painting. Attracted by the social and political developments in his homeland, Rivera traveled alone back to Mexico via Paris in March 1921.

Rivera as a political artist in Mexico

While Diego Rivera was in Italy, José Vasconcelos was appointed Minister of Education by President Alvaro Obregón in 1920. Vasconcelos introduced a comprehensive popular education program that also provided for educational and instructive murals on and in public buildings. With them he wanted to realize the ideals of a comprehensive cultural reform movement following the revolution, which provided for ethnic and social equality for the indigenous population and the establishment of a separate Mexican national culture.

Shortly after Rivera's arrival in Paris in March 1921, he returned to Mexico, as the political and social developments there seemed attractive to him. He took a step back from his time in Europe by developing his own style instead of continuing to follow the stylistic developments of modernity, leaving behind his partner, his lover and his daughter. Only his daughter Marika received maintenance payments through friends, although Rivera never officially recognized paternity. Shortly after his return in June 1921, the Minister of Education accepted Rivera into the government's cultural program. In 1921 Vasconcelos invited Diego Rivera and other artists and intellectuals who had returned from Europe on a trip to the Yucatán . You should familiarize yourself with Mexico's cultural and national heritage so that you can incorporate it into your future work. Rivera saw the archaeological sites Uxmal and Chichén Itzá on this trip . Inspired by the impressions gathered there, Rivera developed his ideas of an art in the service of the people, which should convey the story through murals.

Diego Rivera began painting his first mural at the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria in January 1922 . This project was the prelude and test of the government's mural program. While several painters were working in the courtyard, Rivera made the painting The Creation in the auditorium . The work, in which he largely followed the traditional methods of fresco technique, lasted a year. His first mural took up a traditionally Christian and European motif, even if he contrasted this with typical Mexican colors and figures of this kind. In the panel paintings after his return, however, everyday Mexican life was in the foreground. Rivera married Guadelupe Marín in June 1922 , who was a model for one of the figures in the mural after he had already had relationships with some models. The two moved into a house on Mixcalco Street.

In the autumn of 1922, Diego Rivera helped found the Sindicato Revolucionario de Trabajadores Técnicos, Pintores y Escultores , the revolutionary union of technical workers, painters and sculptors, and got to know communist ideas there. In the union, Rivera was associated with David Alfaro Siqueiros , Carlos Mérida , Xavier Guerrero , Amado de la Cueva , Fernando Leal , Ramón Alva Guadarrama , Fermín Revueltas , Germán Cueto and José Clemente Orozco . In late 1922, Diego Rivera joined the Mexican Communist Party . Together with Siqueiros and Xavier Guerrero, he formed their executive committee.

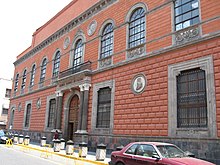

In March 1922 Rivera was commissioned to design the Secretaría de Educación Pública with frescoes. From September 1922 he worked on this project, which he led at the same time. It was the largest commission in the first decade of muralism . The work in the Ministry of Education dragged on for years. Since he was only making two dollars a day doing this, Diego Rivera sold paintings, drawings, and watercolors to collectors mostly from North America. Rivera's daughter Guadelupe was born in 1924. This year there were significant conflicts over the wall painting project in the Ministry of Education. Conservative groups rejected the wall painting, Minister of Education Vasconcelos resigned and work on the project was suspended. After the dismissal of the majority of the painters, Rivera was able to convince the new Minister of Education José María Puig Casaurac of the importance of the murales and then kept his job to complete the paintings. At the end of 1924, in addition to his work in the Ministry of Education, he was commissioned to paint wall paintings in the Escuela Nacional de Agricultura in Chapingo . There he created decorative murals for the entrance hall, the staircase and the reception hall on the first floor and in 1926 the walls of the auditorium. Both his pregnant wife and Tina Modotti modeled Rivera on this project. With Modotti he entered into a relationship, which led to the temporary separation from Guadalupe Marín. After the birth of his daughter Ruth, Diego Rivera left his wife in 1927.

Trip to the Soviet Union and successes in Mexico

In the fall of 1927, after completing the work in Chapingo, Diego Rivera traveled to the Soviet Union on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution as a member of the official delegation of the Communist Party of Mexico . Rivera wanted to visit the USSR as early as his Parisian years, now he hoped to benefit from the development of art there and wanted to make a contribution to Soviet art with his own mural. The trip led via Berlin, where he met intellectuals and artists, to Moscow, where he stayed for nine months. There he gave lectures and taught monumental painting at the School of Fine Arts. Rivera was in contact with the October artist group , who advocated public art that followed folk traditions. During the celebrations on May 1, 1928, he made sketches for a mural planned for the Red Army Club , which, however, was not executed due to intrigues and disagreements. Due to differing political and artistic views, the Stalinist government suggested that Diego Rivera return to Mexico.

In 1928 he returned from the Soviet Union and finally separated from Guadelupe Marín. He finished the murals in the Ministry of Education and Chapingo that year. While he was finishing his work in the Ministry of Education, he received a visit from Frida Kahlo , who showed him her first attempts at painting and asked for his opinion. Due to Rivera's positive reaction, she decided to devote herself entirely to painting. On August 21, 1929, Diego Rivera married the painter, who was almost 21 years his junior. Shortly before that, Rivera had been elected director by the students of the Academia de San Carlos art school . However, his concepts came under heavy criticism from the media and conservative forces. He worked out a new timetable and gave the students great opportunities to have a say in the choice of teachers, staff and methods. Rivera's reforms were mainly criticized by teachers and students of the architecture school housed in the same building, they were joined by conservative artists and members of the communist party, from which Diego Rivera was expelled in September 1929. Eventually the administration of the academy gave in to the protests and dismissed Diego Rivera in the middle of 1930. The expulsion from the Communist Party was the result of Rivera's critical position towards Josef Stalin and his politics as well as the acceptance of government orders under President Plutarco Elías Calles .

In 1929 Rivera was commissioned to paint the staircase of the Palacio Nacional in Mexico City, and he also painted a mural for the Secretaría de Salud . While the work was still going on at the seat of government, which would keep Rivera busy for several years, the US ambassador to Mexico, Dwight W. Morrow , commissioned Diego Rivera to do a mural in the Palacio de Cortés in Cuernavaca . For this assignment he received his highest fee to date, at $ 12,000. After completing this contract in the fall of 1930, Rivera accepted an offer to do murals in the United States. This decision was sharply criticized by the communist press in Mexico.

Stay in the USA

In the fall of 1930, Diego Rivera traveled to San Francisco with Frida Kahlo . In the United States, the art of Mexican wall painters had been known through newspaper articles and travelogues since the 1920s. Travelers had already brought Rivera's panel paintings to the United States, and now he was also to do murals there. The Californian sculptor Ralph Stackpole had known Rivera since his time in Paris and collected his paintings, one of which he gave away to William Gerstle , president of the San Francisco Art Commission . Gerstle wanted Rivera to paint a wall at the California School of Fine Arts , and the latter accepted the assignment. When Stackpole and other artists were commissioned to decorate the new building of the San Francisco Pacific Stock Exchange in 1929 , he also managed to reserve a wall for Diego Rivera. Rivera was initially denied entry to the United States because of his communist sentiments. Only after the advocacy of Albert M. Benders , an influential insurance agent and art collector, did he get a visa. This was criticized both by anti-communist media and by artists from San Francisco, who saw themselves at a disadvantage in the award of contracts. The fact that 120 works by Rivera were exhibited at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor at the end of 1930 also met with criticism . After completing the mural projects and due to the couple's personal appearance, the mood changed for the better.

From December 1930 to February 1931, Diego Rivera painted the mural Allegory of California in the Luncheon Club of the San Francisco Pacific Stock Exchange in San Francisco. The mural was officially inaugurated together with the stock exchange building in March 1931. From April to June 1931 Diego Rivera then made the mural The Realization of a Fresco in the California School of Fine Arts. Immediately after completion of the project, he returned to Mexico to complete the unfinished mural in the Palacio Nacional at the request of the President. Shortly afterwards, Diego Rivera was invited to exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. After a retrospective by Henri Matisse, it was the second major solo exhibition in the museum, which opened in 1929, and remained the most important exhibition of Rivera's works in the USA until 1986. Because of this invitation, Rivera broke off work in the Palacio Nacional again after the main wall had been completed. He traveled by ship to New York with his wife and the art dealer Frances Flynn Paine , who had proposed to him for this retrospective. He arrived in November 1931 and worked on eight portable frescoes by the time the exhibition opened on December 23rd. The retrospective showed a total of 150 works by Rivera and was visited by 57,000 people. The exhibition also received positive feedback.

Through tennis world champion Helen Wills Moody , Diego Rivera met William R. Valentiner and Edgar P. Richardson, the two directors of the Detroit Institute of Arts . They invited him to exhibit in Detroit in February and March 1931 , and proposed to the city's art commission to hire Diego Rivera for a mural in the museum's Garden Court. With the help of Edsel B. Ford , chairman of the city's art committee, Diego Rivera was able to begin preparing his work for Detroit after his New York exhibition in early 1932. Ford made $ 10,000 available for the execution of the frescoes, a fee of $ 100 per square meter painted was planned. When Rivera visited the site, however, he decided to paint the whole courtyard for the same fee instead of the two planned paintings. Rivera depicted Detroit's industry in the frescoes. His industrial painting was criticized for showing pornographic , blasphemous, and communist content, and the safety of the works appeared at times to be jeopardized. Edsel B. Ford, however, stood behind the artist and his work and so calmed the situation.

Still working in Detroit, Rivera was commissioned to paint a mural in the lobby of the Rockefeller Center, which was still under construction . In the course of 1933 he worked on this picture, the subject of which was Man at the Crossroads, hoping for a better future, which had been given by a commission. In this picture Rivera depicts his negative view of capitalism and shows Lenin , who has not yet appeared in the approved preliminary drawing, as a representative of the new society. This led to heavy criticism from the conservative press, whereas progressive groups showed solidarity with the artist. The Rockefellers as clients did not stand behind the artist like Ford, but asked Rivera to paint over Lenin. When the artist refused, the painting was covered in early May, and Rivera was disbursed and fired. As a result, Diego Rivera returned to Mexico. In February 1934, the mural in the Rockefeller Center was finally destroyed.

Return to Mexico

Diego Rivera returned to Mexico in 1933 disappointed because he was unable to freely implement his political works in the United States. He had become one of the most famous artists in the United States, adored by other artists and left-wing intellectuals, and attacked by industrialists and conservatives. After the fresco in the Rockefeller Center was destroyed in February 1934, Diego Rivera was given the opportunity to realize his work in the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City that same year . As a result, the state again awarded public contracts to the great representatives of muralism.

After his return, Rivera and Frida Kahlo moved into the studio house in San Angel, which he had commissioned from Juan O'Gorman in 1931 . Kahlo lived in the smaller, blue cube of the Bauhaus- style building, and Rivera lived in the larger, pink cube. In November 1934, Diego Rivera resumed work in the Palacio Nacional, which he completed in 1935. He completed the ensemble Epos of the Mexican People, consisting of the pictures Pre-Hispanic Mexico - The Ancient Indian World from 1929 and History of Mexico from the Conquest to 1930 from 1929 to 1931 with the picture Mexico Today and Tomorrow . In November 1935, Rivera ended this project. Since there were no further large wall painting projects to come, he devoted himself more to panel painting in the following time, his motifs were often Indian children and mothers. The technical execution of these pictures in the second half of the 1930s was often not particularly good, as Rivera produced them in series and sold them to tourists in order to use the proceeds to finance his collection of pre-Columbian art .

An affair with Frida Kahlo's younger sister Christina led to a temporary marital crisis that Rivera had in 1935. But the common political interests brought the couple back together. Rivera continued to face hostility from the Mexican Communist Party, which accused him of supporting the government's conservative positions. Rivera repeatedly came into conflict with Siqueiros in particular, and the two even faced each other armed at a political meeting. Diego Rivera turned to the Trotskyists as a result of his contacts with the Communist League of America in New York in 1933 and in 1936 became a member of the International Trotskyist-Communist League . Together with Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera worked with President Lázaro Cárdenas del Río to ensure that Leon Trotsky should receive political asylum in Mexico. Provided that the Russian would not be politically active, the president agreed to the asylum application. In January 1937, Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo received Leon Trotsky and his wife Natalia Sedova in Kahlo's blue house in Coyoacán. In 1938 Rivera also hosted the surrealist thought leader André Breton and his wife Jacqueline . The two artists signed a manifesto written by Trotsky for a revolutionary art. The befriended couple traveled together through the Mexican provinces, and under the influence of Breton Diego Rivera made a few surrealistic pictures.

Rivera broke up with Trotsky in 1939 after personal and political strife. In the fall of the same year, Frida Kahlo divorced Rivera. In 1940 he exhibited in the International Surrealism Exhibition organized by André Breton , Wolfgang Paalen and César Moro in the Galería de Arte Mexicano by Inés Amor . In addition, Rivera returned to San Francisco that year, where he had received another mural assignment after a long time. After the Soviet Union made a pact with the German Reich , the artist softened his negative attitude towards the United States and accepted the invitation. He subsequently stood up for the solidarity of American countries against fascism . Under the title Pan American Unity, he painted ten blackboards for the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco. There he and Frida Kahlo remarried on December 8, 1940, as both had suffered from the separation.

After his return to Mexico, Diego Rivera moved to Kahlo's blue house in February 1941. In the following years he only used the house in San Angel Inn as a retreat and studio. In 1941 and 1942 Diego Rivera mainly painted at the easel. He was also commissioned to do the frescoes on the upper floor of the inner courtyard of the Palacio Nacional . He also began building the Anahuacalli in 1942 , where he wanted to present his collection of pre-colonial objects. The building was initially designed as a residential building, but ultimately only housed the 60,000-item collection to which Rivera dedicated himself until the end of his life.

From the early 1940s, Rivera was increasingly receiving national recognition. The Colegio Nacional was founded in 1943 and Rivera was among the first 15 members appointed by President Manuel Ávila Camacho . In the same year, the La Esmeralda art academy, founded the year before, appointed him professor with the aim of reforming art teaching. He sent his students to the country and the streets to paint according to Mexican reality. Rivera also made drawings, watercolors and paintings in this context. After recovering from pneumonia, Rivera painted a large mural in 1947 in the newly built Hotel del Prado on Almeda Park. The dream of a Sunday afternoon in Almeda Park shows a representation of Mexican history through a string of historical figures. In 1943 he was elected an honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters .

Last years of life and death

Together with David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera formed the commission for wall painting of the Instituto de Bellas Artes from 1947 . In 1949 the institute organized a large exhibition on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Rivera's work in the Palacio de Bellas Artes .

In 1950, when Frida Kahlo had to stay in the hospital for nine months because of several operations on the spine, Rivera also took a room in the hospital to be with his wife. This year Diego Rivera illustrated the limited edition of Pablo Neruda's Canto General together with David Alfaro Siqueiros and also designed the book cover. He also designed the set for El cuadrante de la soledad by José Revueltas and continued his work in the Palacio Nacional. Diego Rivera was together with Orozco, Siqueiros and Tamayo the honor of Mexico on the Biennale of 1950 in Venice to represent. He was also awarded the Premio Nacional de Artes Plásticas . In 1951 Rivera realized an underwater mural in the water shaft of the Cárcamo del río Lerma in Chapultepec Park in Mexico City and designed a fountain at the entrance of the building. For the paintings in the basin into which the water is pumped, he experimented with polystyrene in a rubber solution to make the painting possible under the water's surface. In 1951 and 1952 Rivera also worked at the stadium of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México , where he was supposed to depict the history of sport in Mexico in a mosaic. Of this work of art, however, he only completed the center piece of the front picture, as there was insufficient funding.

In 1952, Rivera painted a portable blackboard for the exhibition Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art, planned in Europe . His portraits of Stalin and Mao in this work led to the exclusion of his work. Overall, Rivera turned against the increasingly Western capitalism-oriented policies that had begun under Aleman's presidency. From 1946 Rivera repeatedly applied for re-admission to the Communist Party, while Frida Kahlo was re-accepted into the party in 1949. In 1954 the two took part in a rally in Guatemala to support the government of Jacobo Arbenz . It was the last public appearance of Frida Kahlo, who died on July 13, 1954. Rivera agreed to allow the communist flag to be placed over her coffin during her wake at the Palacio de Bellas Artes, and in return the Mexican Communist Party accepted him back as a member. Thereupon Rivera painted the painting Glorious Victory , in which he showed the fall of Arbenz. The picture was sent through various communist countries and has been lost since the last exhibition in Poland.

Rivera's age and health made it difficult to work on monumental wall paintings, so that in the last years of his life the panel painting became his preferred medium. On July 29, 1955, he married the publisher Emma Hurtado , who had been his gallery owner since 1946. He bequeathed Frida Kahlo's blue house and the Anahuacalli with his collection of pre-Columbian art to the Mexican people. Rivera, suffering from a cancerous ulcer, went to the Soviet Union for medical treatment in 1955. His return journey took him via Czechoslovakia and Poland to the GDR, where he became a corresponding member of the Academy of Arts in East Berlin . Back in Mexico, he moved into the house of his friend Dolores Olmedo in Acapulco , where he was supposed to relax and make a number of seascapes.

On November 24, 1957, Diego Rivera died of a heart attack in his San Angel Inn studio . Hundreds of Mexicans gave him final escort . Instead of combining his ashes with those of Frida Kahlo in her blue house, he was buried in the Rotonda de los Hombres Ilustres in the Panteón Civil de Dolores .

plant

Diego Rivera's complete oeuvre includes panel paintings, wall paintings, mosaics and drawings. The murales in particular are a key to understanding his work and shaped his reception as the most important and influential contemporary Mexican artist. Rivera's works have often been associated with socialist realism as they frequently expressed his political point of view. In fact, there were hardly any stylistic points of contact. Rivera's style and aesthetics, particularly expressed in the large wall paintings, were based on the frescoes of the Italian Renaissance , the Cubist conception of space, classical proportions, the representation of movement in Futurism and pre-Columbian art . His topics were not limited to the observation of social conditions, he also devoted himself to complex historical and allegorical narratives. In doing so, he developed his own expressions.

Panel paintings

The exact number of panels by Diego Rivera is not known. New, previously unknown works keep appearing. They often take a back seat to the murals, but they are of great importance for tracking Rivera's artistic development and as a reference for his further works. In the works of the apprenticeship period in Mexico from 1897 to 1907 and the period in Europe from 1907 to 1921, the development of an artist can be traced, who in a short period of time adapted and further developed various artistic currents and schools in his works. Rivera continued this learning process throughout his life.

In his first paintings, Diego Rivera sought to meet the tastes of the Mexican bourgeoisie at the beginning of the 20th century and thus to become the most successful painter in Mexico. That is why he mainly painted social themes, based on the style of his Madrid teacher Eduardo Chicharro and Ignacio Zulaogas '. He also used extensive symbolism with decadent motifs from the landscapes of Flanders that he traveled to .

Cubist works

| • Sailor at breakfast , 1914 117 × 72 cm, oil on canvas Museo Casa Diego Rivera |

| • Zapatista landscape , 1915 144 × 123 cm, oil on canvas Museo Nacional de Arte |

| • The Mathematician , 1918 Oil on canvas Museo Dolores Olmedo |

| (External links, please note copyrights ) |

In Paris, Rivera made contact with post-impressionism , which had become a reference for modern painting, during his first stay in Europe , which is why he returned to this city in 1911 after a short stay in Mexico. During his second stay in Paris, he created around 200 Cubist works and at times belonged to the group of Cubists until he broke the dispute with this style. Diego Rivera came to Cubism through studying Mannerist painting and El Greco's landscape paintings . In addition, Ángel Zárraga showed him the compositional and optical distortions of modernity. As a result, Rivera created a number of precubist works before he actually painted Cubist from 1913 to 1918, not only adapting the geometrical appearance, but also being aware of the revolutionary content of cubism for the design of time and space. Rivera not only followed the theories of Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso , but developed his own point of view. One of the works typical of Rivera's Cubism is Sailors at Breakfast from 1914. Diego Rivera used a kind of compositional grid with the painting, with which he tried to create simultaneity. The picture shows a man whose blue and white striped shirt and pompom cap with the word Patrie identify him as a French sailor. He sits behind a table and is integrated into the compositional grid. In using this compositional method, Diego Rivera followed Juan Gris , who designed a different object in each field in a consistently maintained perspective, as Rivera did here with the glass and the fish.

Another outstanding work of Rivera's cubist phase is Zapatista Landscape - The Guerrillero , in which the artist expressed his sympathy for the revolutionary developments in his homeland and his admiration for Emiliano Zapata . This iconographic portrait of the revolutionary leader with his symbols referring to the Mexican Revolution such as the zapatista hat, serape , rifle and cartridge belt were viewed as too revealing by some orthodox representatives of Cubism. The resulting dispute led to Rivera's departure from Cubism. He turned to a landscape painting inspired by Paul Cézanne and created the paintings The Mathematician and Still Life with Flowers in 1918 , which were linked to academic painting .

Portraits and self-portraits

| • Portrait of Lupe Marín , 1938 171.3 × 122.3 cm, oil on canvas Museo de Arte Moderno |

| • Tlazolteotl Pre-Columbian / 19. Century? 8 "x 12.07" x 14.92 cm, Aplit Dumbarton-Oaks Collection |

| • Portrait of Ruth Rivera , 1949 199 × 100.5 cm, oil on canvas Rafael Coronel Collection |

| • Portrait of Natasha Zakólkowa Gelman , 1943 115 × 153 cm, oil on canvas Collection Jacques and Natasha Gelman |

| • The sons of my godfather (portrait of Modesto and Jesús Sánchez) , 1930 42.5 × 34 cm, oil on canvas Fomento Cultural Banamex |

| (External links, please note copyrights ) |

The vast majority of Rivera's panel paintings are portraits. In these he went beyond the simple representation of the person and expanded this classic genre through psychological and symbolic references to the person represented. One of the works that exemplifies this genre in Rivera's work is the portrait of Lupe Marín from 1938. It shows Guadalupe Marín , whom Rivera had previously immortalized in paintings and murals. The painting shows the model sitting on a chair in the center of the composition. Your back is reflected in a mirror. In terms of color, brown tones and the white of her dress dominate. Rivera refers to various artistic models in his portrayal. The exaggerated proportions and pose are borrowed from El Greco , the reflection refers to Velázquez , Manet and Ingres . The complex structure of the composition, however, with its overlapping and interconnected planes and axes, shows parallels to Paul Cézanne . In this portrait, Diego Rivera also made direct reference to his fresco in the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria , where he depicted the model as Tlazolteotl , the goddess of purification. In his portrait of Marín Rivera refers to the most famous depiction of this goddess, which is in the Dumbarton Oaks collection in Washington DC and shows her giving birth to a person. The facial expression of Marín is clearly borrowed from this statue.

Rivera also used the mirror motif in the portrait of Ruth Rivera from 1949. It shows his daughter from behind with her face turned towards the viewer. She holds a mirror that shows her face in profile and is framed in sunny yellow, wears strap sandals and a white tunic , which reminds her of a figure of classical antiquity. This representation of family members and caregivers, as in the case of his daughter Ruth or Lupe Marín, was still the exception in Diego Rivera's work. Most of the portraits were commissioned, such as Natasha Zakólkowa Gelman from 1946. It shows the wife of the film producer Jacques Gelman in a white evening dress on a couch. White callas are draped behind her upper body and head and parallel to her lower body . The body position of the sitter refers to the shape of the flower, while the flower, conversely, refers to the essence of the elegant woman. In other portraits, Rivera used clothes that alluded to Mexico in their colors. In addition to this commissioned work, he also made numerous portraits of Indian children such as The Sons of My Gevatters (Portrait of Modesto and Jesús Sánchez) from 1930. These paintings were especially popular with tourists as souvenirs.

Diego Rivera painted numerous self-portraits throughout his career. These mostly showed him as a chest piece, shoulder piece or head picture . His main interest was his face, while the background was mostly just done. In contrast to the commissioned portraits, in which he idealized the sitter, Rivera presented himself extremely realistically in his self-portraits. He was aware that, especially with increasing age, he did not correspond to the ideal of beauty. In the picture Der Zahn der Zeit from 1949, Rivera presented himself as a gray-haired man with a furrowed face. In the background of the picture he showed various scenes from his life. In caricatures Diego Rivera depicted himself several times as a frog or toad . He also used this as an attribute in some of his portraits.

Mexico

| • The threshing floor , 1904 100 × 114.6 cm, oil on canvas Museo Casa Diego Rivera |

| • The Festival of Flowers , 1925 147.3 × 120.7 cm, oil on canvas Los Angeles County Museum of Art |

| • The children ask for accommodation , 1953–54 24.6 × 49.8 cm, oil on canvas, Francisco Gómez Children's Hospital Collection, Mexico City |

| • Dusk in Acapulco , 1956 30 × 40 cm, oil on canvas series, various locations |

| (External links, please note copyrights ) |

Another central theme of Rivera's paintings was Mexico. Already during his apprenticeship, Diego Rivera painted the landscape Die Tenne from 1904, inspired by his teacher José María Velasco . It shows a farmer and a horse-drawn plow in the central foreground. On the right edge of the picture there is a barn, to the left and in the background the picture opens through a gate into the landscape that ends in the background at the Popocatépetl volcano . Following Velasco, Rivera tried to depict the typical colors of the Mexican landscape in the picture. The use of light also goes back to the teacher.

One motif that appeared several times in Rivera's work is the flower sellers, which he painted from 1925 and which were popular with the public. The flowers were not decorative elements but had an emblematic meaning. Diego Rivera knew the flower symbolism from the time before the conquests by the Spaniards. Rivera won an acquisition price at a Pan-American exhibition in Los Angeles in 1925 with a painting showing sellers of Calla ; the painting was acquired by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art . It showed a religious celebration on the Santa Anita Canal, which was part of the disappeared network of canals in and around Mexico City. In addition, Rivera presented customs on his boards, such as in the series Christmas Customs from 1953 and 1954. The second board is entitled The children ask for shelter (Los niños pidiendo posada) . It shows Indian children and their parents with candles during a nightly procession. In the background there is a surface of water in which the moon is reflected and at the front border of which Mary and Joseph can be seen with the donkey on the journey to Bethlehem. Diego Rivera devoted himself to the topic of popular piety .

In 1956 Diego Rivera made a series of small-format seascapes under the title Dusk in Acapulco while on vacation on the coast . Rivera painted the sunsets in bright, emotionally charged colors. These color experiments were an exception in Rivera's oeuvre. The sea in these seascapes is peaceful. The pictures represent Diego Rivera's need for harmony and peace at the end of his life.

Murales

The Mexican muralism between 1921 and 1974 was the first independent American contribution to the art of the 20th century. Diego Rivera was not the first painter of murales, nor was he the undisputed leading figure or the most important theoretician of the muralists, but alongside David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco he was undisputedly one of the most important representatives of this group. His murals also occupy a prominent position in Diego Rivera's work and attracted more attention than his panel paintings, drawings and illustrations. After returning from France in 1921, Diego Rivera, still under the impression of the frescoes he had previously seen in Italy, turned to wall painting, proposed by the Minister of Education José Vasconcelos as a means of spreading the ideals of the revolution and education understood by the people. He made his first mural in January 1922 in the Bolívar Amphitheater of the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria ; it was the touchstone and prelude to his career as a muralist and muralism in general. Large and prestigious assignments followed for Rivera at the Secretaría de Educación Pública , the Palacio Nacional and the Palacio de Bellas Artes . He also made some murals in the United States.

One of the main themes that has run through the mural projects in Rivera's career is creation . In addition, he often addressed his political point of view, perpetuated communist ideas and personalities, in some cases he also expressed the idea of Pan-Americanism . In a large number of depictions, he addressed Mexican history , especially with a view to its pre-Columbian period. At the beginning of his work as a wall painter, Diego Rivera was still strongly influenced by European art. Over time, however, he increasingly developed his own style in which he incorporated Mexican elements.

Escuela Nacional Preparatoria

| • The Creation , (La Creación) 1921–23 fresco |

| (External links, please note copyrights ) |

Diego Rivera made his first mural in the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria . There is the picture The Creation in the Simón Bolívar Auditorium . From the artist's point of view, the work remained unfinished. Instead of painting individual walls, Rivera originally planned the design of the entire ballroom with the work The Fundamental History of Mankind . The first ideas for this work of art came up early on. After the opening of the new ballroom in September 1910, the idea for a mural came up, for the execution of which Rivera was also considered, but whose plans were not carried out due to the course of the Mexican Revolution . Rivera probably visited the room in late 1910, and during his second visit to Europe he had blueprints of the auditorium.

The first sketch for this mural project was made during Rivera's stay in Italy. A reference to Perugia is noted on it. There he could see a two-part fresco in the church of San Severo, the upper part of which had been painted by Raphael and the lower part by Perugino . The three vertically divided pictures influenced Rivera's wall paintings in terms of form and composition. In the first segment, Raphael showed the Holy Spirit as the energy of creation, while Rivera represented a cosmic force. In the middle segment, Raffael showed Christ as Ecce homo , Rivera the first person. In the last segment, the Mexican artist refers to Perugino in the design of the figures. Both the fresco in Perugino and the wall painting by Rivera have an opening in the middle. The former served as a site of a saint, while an organ was installed in the auditorium . Rivera's design was based on basic geometric shapes and followed the golden ratio .

In November 1921, Diego Rivera began designing the 109.64-square-meter mural, which he completed in 1923. He combined Mexican and European elements in it according to his claim to transfer the Mexican tradition into the modern art of the 20th century. For example, he showed a typical Mexican forest with a heron and an ocelot , while giving the figures the physique and skin color of the mestizo . The niche is defined by a large male figure with outstretched arms. On the axis of the picture above her lies a blue semicircle, which is surrounded by a rainbow and three pairs of hands that create humans and distribute the primal energy. In the figures, apart from the two figures of the original couple on the left and right lower edge of the picture, the human virtues and abilities are shown. The semicircle in the upper center of the picture is divided into four equilateral triangles in which numbers are indicated by asterisks: In the first triangle it is three, in the second four, in the third ten and in the fourth two. This refers to the number symbolism of the Pythagoreans , whose special significance of the number ten emphasizes the meaning of the third triangle. The first and fourth triangles refer to the original pair, which is embodied by the naked woman on the left and the naked man on the right side of the wall. The number of stars in both triangles corresponds to five, which was also part of the Pythagorean number mysticism. The four stars of the second triangle refer to the four mathemata , geometry , arithmetic , astronomy and musicology . The four is also repeated in the pairs of hands, three of which surround the circle and one of which belongs to the great figure that represents humanity as a whole. This symbolism used by Rivera refers to the education and the pursuit of virtue, which should be propagated in this picture.

Rivera used the encaustic technique for his fresco . He drew on the dry plaster and applied the color pigments dissolved in wax. These were then burned in with a welding torch.

Secretaría de Educación Pública

In March 1922, Diego Rivera was commissioned by José Vasconcelos to work with a group of young painters to paint the three arcaded floors of the two courtyards in the Secretaría de Educación Pública , while other artists were to decorate the interior of the ministry. The two courtyards are referred to as the courtyard of work and the courtyard of the festivals according to the thematic design of Rivera's mural cycles and together form the work Political Dream Image of the Mexican People . Rivera's work lasted from 1923 to 1928, the project stalled at times when Vasconcelos gave up the post of Minister of Education as a result of political disputes. The work was a political work of art. In the years in which the paintings were created, both the politics of Mexico and the political position of the artist changed significantly. At the beginning of the work Rivera was a leading member of the Communist Party of Mexico , by the end of the work he was critical of Josef Stalin and met with increasing criticism even within the party. A year after its completion, Rivera was even expelled from it. Politically, the victorious revolutionary forces at the beginning of the 1920s were only able to maintain their power with difficulty and were attacked by conservative forces; the government was allied with the Communist Party. Over time, the government managed to stabilize, and by the end of the 1920s, the communists had almost been pushed underground. The murals are a work of art in which these developments are expressed. They combine a wide variety of elements that can be described as realistic , revolutionary , classic , socialist and nationalist . Rivera turned to Mexico as a theme and developed his own style in which he incorporated Mexican elements.

Diego Rivera made more than 100 murals to decorate the courtyards of the Ministry of Education. In them he presented many ideas, some of which were contradicting one another. They cannot be summarized under any overarching metaphysical theme. Rivera negotiated incompatible, resistance and differences in them. He stepped back behind the work himself by instead of immortalizing himself in the pictures, taking up abstract and eclectic European painting, film, politics and anthropology . He made use of a very direct form of rendering his motifs and showed the people in their actual places, with the emblems corresponding to the meaning of the symbols shown. In the yard of work , Diego Rivera developed an allegory on the understanding of the elite, in the yard of the festivals he showed the crowds.

The murals in the courtyard of the work form a related cycle. The central picture of this cycle is in the middle wall field on the second floor. It is the 3.93 meters high and 6.48 meters wide fresco The Brotherhood (La fraternidad) , which shows the alliance of farmers and workers under the care of a sun god . The deity, who is Apollon , spreads her arms cross-shaped over the two men in a cave. These two stand for the workers and peasants as carriers of the revolution. This alliance is the Bolshevik ideal, even if it had a different sign in Mexico, since the main bearers of the revolution were not the workers, but it came from the peasants. But it also symbolizes the connection between man and woman, which is also expressed in the attributes hammer and sickle , which refer to Demeter and Hephaestus . Next to Apollo are the three apotheoses The Preserver , The Herald and The Distributor , which are repeated on the opposite wall. It is an allegorical representation of the Eucharist . Rivera thus integrated religious symbolism into the symbol canon of a secular state. It also echoes Plato's allegory of the cave . Rivera's idealism is expressed in the figure of Apollo, because instead of martyrdom or passion, redemption lies in the rational, pure and radiant male figure. Other motifs in the courtyard of the work are, for example, the liberation of the unfree worker (La liberación del péon) and the teacher in the country (La maestra rural) , which are crowned by the over- port landscape (paisaje) , or various activities such as the foundry (La fundición) , The Mining (La minería) , Potters (Alfareros) , Entrance to the Mine (Entrada a la mina) and The Sugar Cane Factory (La zafara) . There are also some grisaille , which were made mainly on the mezzanine and have esoteric meanings.

- Yard of work

Symbol (agriculture) , grisaille

The Hof der Feste is discussing the project of setting up a new calendar . On the ground floor on the south, north and west walls are the central murals The allocation of community pastures , the street market and gathering , which show secular festivals. They are large, cross-door compositions, while the side wall panels show religious celebrations. The images show the mass of people and point to reality, while the yard of the work also has a metaphysical reference. The allocation of community pastures relates to one of the central demands of the Mexican Revolution . Rivera presented the handover of the expropriated property to the community as a new social contract. In the center of the murals, an officer leads the meeting with a sweeping gesture. While the men are on the streets, the women are on the rooftops. In addition, the deceased are shown, such as Emiliano Zapata , who is sitting on a horse on the right edge of the picture. Diego Rivera's murales are reminiscent of the representations of angel choirs in the Renaissance, such as in paintings by Fra Angelico . This strictly ordered composition reflects the strong ritualization of village politics. With the gathering , Rivera made a doctrinal fresco in which he consciously worked with left and right as a principle of order. On the left, in Bolshevism on the side of the progressive and revolutionary class, the painter depicted the workers in the form of two injured figures teaching children. The worker leader with his fist raised speaks to the workers on the left side of the wall. On the right side the people are shown in shadow, while on the left side they lie in the light. With this lighting, Rivera demonstrated the difference between left and right. On the right edge of the picture in the foreground are Zapta and Felipe Carillo Puerto , the governor of Yucatán, two of the slain heroes of the revolution. The street market portrays the government's attempt to strengthen agriculture and revitalize pre- capitalist trade . In this mural, Rivera did not try so much for compositional order, but instead made the multitude of people appear in waves and deliberately showed the chaos on the market square. In contrast to the first two, this large mural ties in with old traditions instead of breaking with them. In addition, other festivals and events related to the course of the year were shown in the courtyard, such as Day of the Dead , The Corn Festival and The Harvest . On the first floor Rivera painted the coats of arms of the states, on the second floor the ballad of the peasant revolution . In one of the central frescoes of this cycle, Im Arsenal (en el arsenal) , Rivera depicted the young Frida Kahlo , whom he had met shortly before, handing out rifles to the revolting workers.

- Courtyard of the festivals

The murales in the Ministry of Education were supposed to represent the new reality after the revolution. As a result of the upheavals, an extensive interdisciplinary study was carried out under the direction of Manuel Gamio , which was published in 1921 as The Population of the Teotihuacán Valley . She took up older racial theories about the mestizo and understood evolution as a development towards the complex, while the mestizo were propagated as an ideal. Diego Rivera used photographs from the publication and depicted dark-skinned, squat peasants and workers with pointed and blunt noses who were clad in white. In doing so, he gave social legitimacy to the studies and theories that were spread in The People of the Teotihuacán Valley .

Palacio Nacional

Diego Rivera's main work of muralism are the wall paintings in the Palacio Nacional , the parliament building and government seat of Mexico. Between 1929 and 1935 he painted the epic of the Mexican people in the main staircase; between 1941 and 1952, pre-colonial and colonial Mexico followed in a corridor on the first floor.

The epic of the Mexican people comprises a total of 277 square meters of wall space in the central stairwell. The north wall shows the mural Old Mexico , on the west wall Rivera painted the fresco From the Conquest to 1930 and on the south wall he completed the cycle with Mexico today and tomorrow . In a circle they form a homogeneous whole. The first phase of work in the Palacio Nacional was started by Diego Rivera in May 1929 and lasted 18 months until it was completed on October 15, 1930 with the painting of the signature on the fresco The Ancient Mexico . While this work was still in progress, Rivera sketched the other murals. In November of that year he traveled to the United States and left the mural unfinished. In June 1931, Diego Rivera returned to Mexico City to paint the main wall. He worked on it for the five months from June 9th to November 10th, 1931, before traveling again to the USA to paint. Rivera concluded his cycle of frescoes in the stairwell of the Palacio Nacional with Mexico Today and Tomorrow , painted between November 1934 and November 20, 1935 . With the signature of this fresco the 25th anniversary of the Mexican Revolution was celebrated.

In the center of the composition of the fresco Ancient Mexico is Quetzalcoatl in front of the Sun and Moon pyramids of Teotihuacán , with which the Lord of the Mesoamerican cultures and the largest pre-Columbian metropolis are integrated into the picture. The volcanoes refer to the Anáhuac Valley , from which the Toltecs had established their rule. The feathered snake rises from the volcano in the upper left corner of the picture as the animal embodiment of the Quetzalcoatl. It is repeated in the upper right half of the picture, where it bears its human counterpart. In the right half of the picture Diego Rivera depicted handicraft and agricultural activities, in the left half he showed a warrior on a pyramid, to whom tribute is being made. In the lower left corner there is an armed conflict between Aztec warriors and the peoples they rule.

From the conquest to 1930 , the story traces after the conquest in episodes that merge into one another. The fresco is divided into three horizontal zones. The lower one shows the Spanish conquest of Mexico , the middle episodes of colonization and the upper one, in the arched fields, the interventions of the 19th century as well as various actors in the politics and history of Mexico in the late 19th century and the Mexican Revolution. In the lower center of the fresco, Rivera painted a battle scene between Spaniards and Aztecs, with the central figure, Hernán Cortés, sitting on a horse. From the right side, Spanish soldiers fire with muskets and a cannon , showing Rivera her technological superiority. In the middle of the picture the colonial period is shown, so that the destruction of the Indian culture and the Christianization through the representation of clergy and Cortéz with his Indian wife Malinche are shown. In the middle of this zone, Mexican independence is shown. In the upper zone on the right you can see the American intervention from 1846 to 1848 and the French intervention in Mexico from 1861 to 1867. Numerous historical figures from the reign of Porfirio Díaz and the Mexican Revolution are depicted in the three central arches . In the center of the fresco, the heraldic animal of Mexico , the eagle , is depicted on the opuntia , with Indian standards in its claws instead of the cactus.

The cycle in the stairwell of the seat of government was completed by Diego Rivera with the fresco Mexico Today and Tomorrow . In it he devoted himself to the post-revolutionary situation and gave a utopian outlook. On the right edge of the picture the struggle of the workers with the conservative forces is shown, with Rivera also showing a hanged worker and peasant. In the top right corner of the picture, a worker is agitating and calling for a fight. In the center of the fresco there are box-shaped spatial structures in which, for example, capitalists are shown around a stock market ticker , President Plutarco Elías Calles with evil advisers and the church in a state of debauchery. In the foreground Rivera painted his wife Frida Kahlo and her sister Cristina as village teachers and, towards the left edge of the picture, workers. The central figure at the top middle of the picture is Karl Marx , who is holding a sheet of paper with an extract from the Communist Manifesto and pointing with his right arm to the top left corner of the picture, where Rivera painted the utopia of a socialist future.

Between 1941 and 1952 Diego Rivera painted the cycle Pre-Colonial and Colonial Mexico in a corridor on the first floor of the government palace . The frescoes cover a total of 198.92 square meters. Originally, 31 transportable frescoes were planned to be placed on the four sides of the inner courtyard. Ultimately, Rivera only made eleven frescoes and interrupted the project several times. Its theme is a synthetic representation of the history of Mexico from the pre-Columbian period to the constitution of 1917. The reference to the indigenous cultures of Mexico, their customs, activities, art and products aimed at the consolidation of the national identity. Rivera chose colorful and grisaille frescos as a form of representation . The great fresco The great Tenochtitlan (view from Tlatelolco market) shows Diego Rivera's vision of the ancient Aztec capital , Tenochtitlan . In front of the panorama of the urban architecture around the Templo Mayor , the market activities such as the animal trade, the trade in food and handicraft products as well as representatives of the various social classes such as traders, officials, medicine men, warriors and courtesans are depicted. In other wall panels, for example, arable farming with crops unknown to Europeans and individual handicraft activities are shown. Another large fresco shows festivals and ceremonies of the Totonaks and the culture of El Tajín such as the worship of the goddess Chicomecoatl . In the foreground you can see visitors to the site making sacrifices. In the last fresco of this cycle, Rivera is dedicated to the Spanish conquest of Mexico and the colonial era. Above all, he wanted to show the subjugation and exploitation of the Indians and portrayed Hernán Cortés in a grotesque way. In this last fresco of the ultimately unfinished project it becomes clear that Diego Rivera contrasts the idealized splendor of the pre-Columbian era with his negative judgment of the conquest and conquistadors wanted to.

- Pre-colonial and colonial Mexico

Detroit Institute of Arts

Diego Rivera's outstanding work from his time in the United States is his murales at the Detroit Institute of Arts . They are considered the best work by Mexican muralists in the United States. The theme of these frescoes was Detroit's industry . The frescoes cover 433.68 square feet and have received various titles such as Detroit Industry , Dynamic Detroit, and Man and Machine . Rivera visited the Ford River Rouge Complex in Dearborn , a facility where all automobile manufacturing took place. He arrived in Detroit when the Michigan auto industry was in crisis, but did not depict it in his factories, but told a development of the industry and glorified technical progress. During his exploration of the Ford factory, which lasted about a month, he made numerous sketches. He and Frida Kahlo were also accompanied by William J. Stettler , who took the photographs that Rivera used in his work and made film material. In addition to these impressions of industrial work, Rivera also resorted to earlier works of his work. In addition, he was so fascinated by the industry that instead of the two wall surfaces he had ordered, he wanted to paint the whole courtyard. For this he received the approval of the responsible commission on June 10, 1932. On July 25th of that year Rivera began painting.

In the courtyard of the Detroit Institute of Arts, Rivera produced a closed cycle in which he represented the entire process of automobile production. He showed the different steps in raw material processing and the different activities of the workers during the day. The cycle begins on the east wall of the courtyard with the depiction of the origin of life. This is symbolized by a human fetus . To the left and right below him plowshares can be seen as symbols of human industrial activity. On the wall there are also women with grain and fruits. On the west wall, air, water and energy are symbolized by the aviation industry, shipping and electricity production. Rivera painted civil aviation as opposed to its military use. This juxtaposition was taken up again in the symbols of the dove and the eagle for peace and war. In addition, the painter was referring to a branch of Ford's company with this depiction. The north wall and south wall are crowned by two guardian figures representing the four races represented in the American workforce and holding coal, iron, lime and sand as mineral resources in their hands . These elements were the raw materials for automobile production. Rivera painted the production of the Ford V-8 in the two main areas of the north and south walls . Some of the workers are portraits of Ford employees and Rivera's assistants.

The murales that Diego Rivera painted for the Detroit Institute of Arts have faced criticism for a variety of reasons. On the one hand, American painters who were not commissioned during the Great Depression criticized the fact that Rivera was a lucrative Mexican commissioner; on the other hand, the content of the frescoes, which was supposed to advertise Ford, was criticized. Diego Rivera was defended by the director of the museum, particularly in relation to the latter allegation. Edsel B. Ford knew what Rivera would paint when he agreed to support the project. His support and Rivera's visits to the Ford plant were also based on the fact that Ford was the only automaker with an interest in modern art . Another critic was Paul Cret , architect of the Detroit Institute of Arts, who saw the painting of the walls as an affront to his architecture. In addition, some of Rivera's motifs met with criticism from ecclesiastical and religious sides and were described as pornographic . The press took a stand against the murales, other artists and art experts such as museum directors, to whom the director had turned, defended the pictures. Ultimately, Ford stood behind the artist and the work, the reception of the frescoes by the workers was positive and the tenor of national reporting also changed for the better.

Palacio de Bellas Artes

Diego Riveras Murales Man at the Crossroads / Man Controls the Universe (El hombre en el cruce de caminos / El hombre controlador del universo) for the Rockefeller Center , where the picture was destroyed, and the Palacio de Bellas Artes , where it ultimately executed deal with the social, political and economic issues of the mid-1930s. The composition of the mural is very dense and also visually tightly structured. The central figure is a worker with his head, shoulders, arms, and gloved hands positioned where two large ellipses intersect. One ellipse shows a telescope image of the sun , the moon and a star nebula , the other a microscope image of a cell . The worker controls a large machine with a joystick and a control panel, which controls the irrigation system of the plants at the bottom of the screen, thus increasing their yield. Overall, it stands for the fact that people master science, medicine, industry and agriculture with modern technology. The worker has a scowl on his face, indicating that Rivera has made a fundamental decision. To the right and left of him, the two choices are represented by elements that Rivera saw as typical of the Soviet and American social systems. In the left half of the picture, to the right of the worker, there are war scenes with fighter planes, tanks and soldiers wearing gas masks with rifles and a flamethrower. Beneath it, Rivera showed how mounted police beat up demonstrating unemployed people on the corner of Wall Street and Second Avenue. He also portrayed the financial magnate John D. Rockefeller, Jr. together with people playing, flirting and drinking. To the left of the worker, on the right side of the fresco, you can see a worker and a soldier shaking hands in front of Lenin . In front of the Kremlin and the Lenin mausoleum , male and female workers gather peacefully on Red Square . In addition, female athletes can be seen running. The decision of the worker in the middle of the composition for one of the two options has not yet been made. Diego Rivera made this clear by giving both the same area.

Originally, this fresco was to be painted in the newly built Rockefeller Center, where it was to be titled The Man at the Crossroads, Insecure, but Looking Hopefully and with the Great Vision of a New and Better Future . Rivera had been invited to a competition alongside Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso , but turned it down. In the end, however, he received the commission because Picasso did not respond to the invitation and Matisse saw no appropriate place for his art in the busy entrance hall. Rockefeller's advisor, Hartley Burr Alexander , suggested an explicitly political motif for the proposed mural. Rockefeller pursued a socio-political line that provided for works councils and a balance between industrialists and workers, but the appointment of a well-known communist artist like Rivera was a surprise. A role in this may have been the support of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller , who had previously collected works of art by Diego Rivera. Added to this was his high international reputation and his fame for murals in Mexico and the United States.

In late March 1933, Diego Rivera arrived in New York to begin the fresco. During this time, the political situation had worsened as a result of Franklin D. Roosevelt's policies within the framework of the New Deal and Hitler's appointment as Chancellor . This prompted Rivera to change his design. He now placed the individual worker at the center of his composition and he chose drastic images to contrast the situation in the USA and the Soviet Union. He also added the portrait of Lenin. The Rockefellers felt increasingly provoked by this ideological development of the image. In December 1933, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. considered moving the unfinished fresco to the Museum of Modern Art . However, this idea was discarded. It was finally destroyed on February 9, 1934. After the fresco was destroyed in New York, Rivera asked the Mexican government for an area where he could paint this picture again. Eventually he was commissioned to do this in the Palacio de Bellas Artes. Rivera completed the fresco in 1934.

Judgment and importance

Alongside David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera is considered the most important modern painter in Mexico. Together they were known as Los Tres Grandes (The Big Three) . Rivera contributed to the development of an independent Mexican art after the revolution and to the establishment of muralism , the first non-European contribution to modern art. Rivera's murals occupy a prominent position in the art of Mexico. They attracted more attention than his panel paintings, drawings and illustrations and have partly suppressed and superimposed the appreciation for his further, multifaceted work. Rivera was controversial outside of Mexico, but still became the most cited Hispanic American artist.

Rivera's oeuvre cannot be assigned to a uniform style. Rivera received a classical education based on the European model in Mexico, whereby he was already sensitized to typical Mexican elements by some of his professors. In Europe, his panel painting went through various styles in a short time. At times he belonged to the group of Cubists , in which he was not only a follower, but also developed his own theoretical positions and represented them without fear of conflict. Even in later times, Diego Rivera anticipated different styles in his panel painting, for example he took up surrealism in two paintings in the mid-1930s . In his murals, Rivera finally developed his very own style, which he also adopted in his paintings. He combined the fresco technique he had studied in Italy with Indian elements, communist and socialist statements and the representation of history. He had a formative effect and achieved fame and fame. The Mexican Nobel Prize for Literature, Octavio Paz, described Rivera as a materialist . He stated: “Rivera adores and paints above all matter. And he sees her as a mother: as a large womb, a large mouth and a large grave. As a mother, as a magna mater, who devours and gives birth to everything, matter is a female form that is always at rest, sleepy and secretly active, constantly giving life like all great fertility goddesses. ”Diego Rivera grasped the image of the fertility goddess and creation directly in many of him Works on. Paz also described the abundance of Rivera's images and their “dynamic of a dialectical understanding of history, consisting of opposites and reconciliations. That is why Rivera also slips into the illustration when he tries to get at the story. ”According to Paz, this representation of the story corresponds to an allegory shaped by Marxism , which shows either the forces of progress or reaction or both in opposition to one another in all works.