Chichén Itzá

| Pre-Columbian city of Chichén Itzá |

|

|---|---|

|

UNESCO world heritage |

|

|

|

|

Kukulcán pyramid |

|

| National territory: |

|

| Type: | Culture |

| Criteria : | i, ii, iii |

| Reference No .: | 483 |

| UNESCO region : | Latin America and the Caribbean |

| History of enrollment | |

| Enrollment: | 1988 (session 12) |

Coordinates: 20 ° 41 ′ 3 ″ N , 88 ° 34 ′ 7 ″ W.

Chichén Itzá is one of the most important ruins on the Mexican Yucatán Peninsula . It is located about 120 kilometers east of Mérida in the state of Yucatán . Its ruins date from the late Mayan period. With an area of 1547 hectares, Chichén Itzá is one of the most extensive sites in the Yucatán. The center is occupied by numerous monumental representative buildings with a religious and political background, from which a large, largely preserved step pyramid protrudes. In the immediate vicinity there are ruins of houses of the upper class.

Between the 8th and 11th centuries , this city must have played an important national role. How exactly this looked like, however, has not yet been clarified. It is unique how different architectural styles appear side by side in Chichén Itzá. In addition to buildings in a modified Puuc style, there are designs that have Toltec features. In the past, this was often attributed to the direct influence of emigrants from central Mexico or conquerors from Tula . Today one starts out more from diffusionistic models and assumes a large degree of simultaneity of different styles in the monumental buildings.

The tourist development of the Yucatán has made Chichén Itzá the archaeological site that attracts the most visitors in Mexico after Teotihuacán . From the UNESCO Chichen Itza was created in 1988 to World Heritage declared. On March 30, 2015, the memorial was included in the International Register of Cultural Property under the special protection of the Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict .

etymology

The name of the city comes from the Yucatec Maya and means "At the edge of the fountain of the Itzá". It is composed of the three words chi ' ("mouth, edge, bank"), ch'e'en ("fountain" or "cave with water") and itzá (the people's own name).

The “fountain” in the name of the city meant the water-bearing sinkhole ( cenote ), which is now known as the Cenote Sagrado . Chichén Itzá is located in a very uneven karst terrain with generally but only slight differences in altitude, which is littered with many collapsing dolines (locally referred to as rejolladas ); these usually do not extend to the groundwater horizon , but offer favorable conditions for planting for microclimatic reasons. A water-bearing sinkhole is located north (Cenote Sagrado) and south ( Cenote Xtoloc, next to the small temple of the same name) of the center. It is certainly no coincidence that the ceremonial center lies exactly between these two cenotes.

In the Chilam-Balam book of Chumayel, another name is mentioned that the city had before the arrival of the Itzá. How this name - Uuc Yabnal - is to be understood has not yet been satisfactorily clarified.

Research history

Colonial reports

In 1533 - almost ten years before the Spaniards had completed their conquest of the Yucatán - Francisco de Montejo the Younger built a small settlement under the name Ciudad Real in the ruins of Chichén Itzá . So far, no archaeological traces of the simple dwellings built at that time have been secured. The settlement was besieged by Indians and could not be held. Diego de Landa (who was not there himself at the time) reports that the pressure was so strong that the Spaniards could only secretly retreat at night. Landa, who came to Yucatán in 1549, gives a very detailed description of some buildings in the center of Chichén Itzá - namely the Castillo and the two small platforms - as well as of the wide road to the Sacred Cenote and of objects that he found there. Antonio de Ciudad Real left a brief note about his visit to the ruins on July 26, 1588 .

Early modern descriptions and research

One of the earliest modern visitors in 1840 was Baron Emanuel von Friedrichsthal , then the first secretary of the Austrian legacy in Mexico. He also took on daguerreotypes , but could no longer publish his report. In 1841, John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick Catherwood spent a long time in Chichén Itzá, making detailed descriptions and drawings. The reports written by Stephens made the Central American ruins, including Chichén Itzá, known to those interested in North America and Europe. Among other things, they inspired the French Désiré Charnay to go on research trips. He visited Chichén Itzá in 1860 and took numerous photographs there.

Modern research

The New York amateur archaeologist Augustus Le Plongeon undertook the first excavations from 1875 onwards. However, the historical representations that he developed in detail in his works belong in the realm of the imagination. He was followed in quick succession by Teoberto Maler , who left only sparse notes besides photographs, and the Englishman Alfred Percival Maudslay , who devoted half a year to the ruined city. The American diplomat Edward Thompson bought the hacienda on the site of Chichén Itzá in 1894 and did research there until the 1920s. Among other things, he excavated the deposits in the Holy Cenote from 1904, where he also undertook diving expeditions. He was charged with illegally taking numerous valuable objects out of the country, but these charges were later dropped as unfounded.

From 1924, the Carnegie Institution of Washington under the direction of Sylvanus Griswold Morley and Mexican government agencies carried out excavations and reconstructions. The archaeologists of the Carnegie Institution (including Eric Thompson ) worked on ruins on the large platform (especially the Warrior Temple), the Caracol, the Monjas and the Mercado, as well as the Temple of the Three Doors, located far south. The archaeologists of the Mexican Antiquities Authority carried out restoration work on the Castillo, the large ball playground , the Tzompantli, the platform of the eagles and jaguars and the platform of Venus. The extensive excavations of the Carnegie Institution in Chichén Itzá laid the foundation stone for the chronology of the entire northern Yucatán based on the pottery found. Scientists from the Carnegie Institution also developed the view that in Chichén Itzá the culture of indigenous Maya and immigrant Toltecs met, which can be recognized by different architectural styles. The Carnegie Institution and later the Mexican INAH ( Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia ) also carried out an exact mapping of Chichén Itzá, which covers many times the area that is now accessible to tourists.

More recent excavations and restorations by the INAH since the 1980s (mostly under the direction of the German Peter J. Schmidt) have concentrated on follow-up examinations and consolidations in the center of Chichén Itzá (completion of the Castillo, the temple of the great sacrificial table, the eastern part of the Thousand Column complex, Osarios) and new excavations in the south (entire Grupo de la Fecha). In 2009 new excavations began in the area around the Castillo under Rafael Cobos.

Current problems

The history of Chichén Itzá's property is unusual and has a not inconsiderable influence on research and conservation: after Edward Thompson's death in 1935, his heirs sold the hacienda to the Yucatec Barbachano family, who had been influential since the 19th century and who now run two hotels there . Although the area of Chichén Itzá was officially declared an archaeological site and is therefore actually a federal territory (zona federal) , this did not have any consequences under private law. In March 2010, the last owner, Hans Jürgen Thies Barbachano, sold a part of the Chichén Itzá site with an area of 80 hectares, which includes the most important buildings of the old city, to the government of Yucatán for 220 million pesos (around 13 million euros ). On the site of the old city there are not only several hotels, but also settlements of the local population.

History sources

There are three different types of information sources available for the history of Chichén Itzá, each illuminating different subject areas:

- the archaeological findings from excavations and recording of surface finds as well as measurements

- The inscription texts in the Maya hieroglyphic writing

- The written reports from the time after the Spanish conquest

It is not uncommon for the information from the three types of sources to be inconsistent and, to a considerable extent, contradicting one another, because it was generated in different situations. Archaeological findings are the unintended outcome of human life and are therefore not consciously altered or focused. However, the uneven chances that traces from different areas of life are reflected in material finds and the preservation conditions in the soil act as a filter through which only parts of the past reality of life can be recognized. Contemporary written monuments, on the other hand, are subject to a different thematic selection: here it was the local rulers who had themselves and their dynasties and their deeds carved in stone for their own glorification. The third group of sources, which were written centuries after the events described, are shaped by the perspective of their authors and the intentions pursued with the writing. Here the texts of Spanish clerics and those of Indian village scribes differ fundamentally. In addition, the different access of the authors to the information and the inevitable distortions to which they were already subjected play a decisive role.

Archaeological sources

According to the types of pottery found, Chichén Itzá has a settlement history of approximately two thousand years. However, buildings can only be verified for the late classical period around 750 AD, which corresponds to the cultural development in the Puuc style further south-west. This was followed by different designs in the end classic, which were associated with a Toltec influence or even the presence of emigrants or conquerors from Tula until the 1970s . During this time, the buildings on the large terrace with the ball playground, the castillo, the warrior temple and the thousand-column complex up to the so-called mercado, but also in other parts of the now enormously grown city. Today one assumes a large simultaneity of the “Toltec” and a modified Puuc style associated monumental buildings. How the sometimes striking stylistic similarities between Tula and Chichén Itzá can be explained historically has not yet been resolved.

Chichén Itzá ruled directly over a smaller area, as the inscriptions in nearby places show. Isla Cerritos is believed to have served as the port for trading activities evident in materials from the north and central Mexican highlands, Guatemala , Costa Rica, and western Panama . In the post-classical period, the city was slowly depopulated and only visited by pilgrims who made offerings in the ruins, as has been proven in many other places.

Hieroglyphic inscriptions with dates

The following overview of the data in hieroglyphic inscriptions from Chichén Itzá and the nearby places Halakal and Yula is based on a list by Nikolai Grube and has been updated. It shows that hieroglyphic inscriptions (with two exceptions) only exist for a very short period of around 60 years.

| Long count | to do | k'atun ... ajaw | Calendar round | monument | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [10.0.2.7.13] | 9 Ben 1 Sak |

4.8.832

|

Templo de las Jambas Jeroglíficas | ||

| [10.1.15.3.6] | 11 Kimi 14 pax |

11/17/864

|

So-called Ballcourt Stone (reading unclear) | ||

| [10.1.17.5.13] | 11 Ben 11 Kumk'u |

9.7.867

|

Hacienda, so-called door bar of the water trough | ||

| [10.2.0.11.8] | 10 Lamat 6 sec |

2.4.870

|

Halakal door beam | ||

| [10.2.0.1.9] | 6 Muluk 12 Mak |

5.9.869

|

Casa Colorada, HG Band | ||

| [10.2.0.15.3] | 1 | 1 | 7 Ak'b'al 1 Ch'en |

6.6.870

|

Casa Colorada, HG Band |

| [10.2.1.0.0] | 1 | 1 |

870

|

Akab Dzib door beam | |

| [10.2.4.2.1] | 2 Imix 4 Mak |

874

|

Yula door beam 2 | ||

| [10.2.4.8.4] | 8 K'an 2 Pop |

7.1.874

|

Yula door beam 1 | ||

| [10.2.4.8.12] | 3 Eb 10 Pop |

12.1.874

|

Yula door beam 2 | ||

| 10.2.9.1.9 | 9 Muluk 7 Sak |

7/30/878

|

So-called door bar of the initial series | ||

| [10.2.10.0.0] | 10 | 1 |

879

|

Templo de los Tres Dinteles, door beam 1 | |

| [10.2.10.0.0] | 10 | 1 |

879

|

Templo de los Tres Dinteles, door beam 2 | |

| [10.2.10.0.0] | 10 | 1 |

879

|

Templo de los Tres Dinteles, door beam 3 | |

| [10.2.10.11.7] | 8 manik 15 weeks |

8.2.880

|

Monja's door beam 1 | ||

| [10.2.10.11.7] | 8 manik 15 weeks |

8.2.880

|

Monja's door beam 2 | ||

| [10.2.10.11.7] | 8 manik 15 weeks |

8.2.880

|

Monja's door beam 3 | ||

| [10.2.10.11.7] | 8 manik 15 weeks |

8.2.880

|

Monja's door beam 4 | ||

| [10.2.10.11.7] | 8 manik 15 weeks |

8.2.880

|

Monja's door beam 5 | ||

| [10.2.10.11.7] | 8 manik 15 weeks |

8.2.880

|

Monja's door beam 6 | ||

| [10.2.10.11.7] | 8 manik 15 weeks |

8.2.880

|

Monja's door beam 7 | ||

| [10.2.11.0.0] | 11 | 1 |

880

|

Akab Dzib | |

| [10.2.12.1.8] | 9 Lamat 11 Yax |

13.7.881

|

Templo de los Cuatro Dinteles, door bar 1 | ||

| [10.2.12.2.4] | 12 K'an 7 Sak |

29.7.881

|

Templo de los Cuatro Dinteles, door beam 2 | ||

| [10.2.12.1.8] | 9 Lamat 11 Yax |

13.7.881

|

Templo de los Cuatro Dinteles, door beam 3 | ||

| [10.2.12.1.8] | 9 Lamat 11 Yax |

13.7.881

|

Templo de los Cuatro Dinteles, door beam 4 | ||

| [10.2.13.13.1] | 4 Imix 14 Sip |

26.2.883

|

Monjas, eastern cultivation, vaulted capstone | ||

| [10.2.17.0.0] | 17th | 1 |

886

|

Caracol stele 1 | |

| [10.3.1.0.0] | 1 | 12 |

890

|

Stele 2 | |

| [10.8.10.6.4] | 10 K'an 2 Sotz ' |

998

|

Osario, pillar | ||

| [10.8.10.11.0] | 2 ajaw 18 moles |

998

|

Osario, pillar |

All data of the long count in square brackets are calculated. The spelling of the dates on the monuments is either exclusively as a calendar round or exclusively or additionally in the spelling “ do [number] in k'atun which ends with the day [number] ajaw ”. The k'atun 1 ajaw is expressed in the long count as 10.2.0.0.0.

Colonial and later texts

Chilam Balam books

Of the Yucatán village books from the 17th and 18th centuries, known under the collective name of Chilam-Balam books, three (those named after the places where they were found, Tizimín and Chumayel, and the Codex Pérez) contain chronicle-like lists of years in the form of k'atun [Number] ajaw. These annual data include brief, often not very clear statements about events. Since the 13 possible names of the k'atun, which lasts almost 20 years , are repeated after around 256.27 years, it is not possible to make clear statements about the time within a longer period of time. In order to determine European dates, other aspects must therefore also be used, which change as research progresses. The contradictions between the chronological order in the various sections of the Chilam Balam texts lead to further problems of interpretation. The Chilam Balam books also contain prophecies in which events are linked again with k'atun data. These events are partly reflections of historical events and can possibly be used to illuminate them.

Spanish writings of the 16th century

The most important source is the report of the Franciscan and later Bishop Diego de Landa (only preserved in a later, probably heavily edited copy) . In addition, information is given by the 50 Relaciones [geográficas] de Yucatán, reports from the years 1577 to 1581, which were drawn up on the basis of an official questionnaire on all aspects of the country by local administrative officials with the help of Indian informants. For parts of the Yucatán, many of the reports are based on information from the Maya chronicler Gaspar Antonio Chi and are therefore not to be regarded as independent of one another. Works by other mostly Spanish authors contain only individual information.

Historical reconstruction

The reconstructed history differs fundamentally depending on the source used. While the hieroglyphic texts offer the self-portrayal of a small excerpt from a ruling dynasty, the colonial and later written texts consist of largely unconnected, brief individual messages that can only be combined to form questionable depictions. Overall, most of the history of Chichén Itzá is still (and probably forever) unknown.

History according to hieroglyphic inscriptions

The inscriptions cover only a relatively short period in the history of Chichén Itzá, essentially a ruling family, especially its important exponents.

According to the inscriptions, Ek Balam , which was clearly oriented towards the core area of the Classical Maya culture far to the south, held the predominance in the northern Yucatán. Chichén Itzá also seems to have been subordinate to Ek Balam at first. The series of inscriptions in Chichén Itzá, which are reliably dated with Mayan dates, begins with a long horizontal band in the front room of the Red House (Casa Colorada). In this inscription, its authors clearly set themselves apart from the inscriptions by Ek Balam by using a local language form that later appears as Yucatec Maya .

The inscription first tells of a ceremony for the year 869 that K'ak'upakal K'awiil ("Fire is the shield of K'awiil ") performed, the outstanding figure in the inscriptions of Chichén Itzá. Almost a year later, fire ceremonies took place in which K'ak'upakal and K'inich Jun Pik To'ok ', rulers of Ek Balam, were involved, as well as an apparently equal member of the Kokom family known from colonial times . K'ak'upakal is mentioned for the last time in an inscription from 890. The name of his brother, the second important figure in Chichén Itzá, is tentatively read as K'inil Kopol. Like his brother, he bears a ruler title that does not occur elsewhere, but is only mentioned in inscriptions between 878 and 881. Her mother was Ms. K'ayam, while the father, with a name that was not read satisfactorily, remains indistinct, which should correspond to an emphasis on maternal descent in Chichén Itzá.

K'ak'upakal and K'inich Jun Pik To'ok 'also appear on a monument in nearby Halakal, presumably together with an as yet unidentified local ruler. K'ak'upakal also appears in neighboring Yula, along with the local ruler To'k 'Yaas Ajaw K'uhul Um and other people in connection with fire ceremonies. In the building of Chichén Itzá known today as Akab Dzib , Yahawal Cho 'K'ak', a member of the Kokom family, describes himself as the owner. But other inscriptions from unidentified buildings also relate them to the Kokom.

The dates given in the inscriptions on buildings reveal three construction periods. The oldest, which lies before the rise of the K'ak'upakal, includes the buildings Akab Dzib and Casa Colorada, the next includes the construction of the Monjas complex . The last include the buildings of the Grupo de la Fecha and the temples of the three and four lintels, all built on behalf of K'inil Kopol. This also ends the dense series of dated inscriptions. There are no inscriptions that could provide information about the exact time of construction and the people involved for the later period in which the buildings known as Toltec were built. It can be concluded from this that the ability to write inscriptions either no longer existed or was no longer valued.

Numerous names that were seen in earlier research as members of a relatively egalitarian system of rule under the Mayan name multepal are now recognized as names of gods, which means that the supposed peculiar political structure can no longer be assumed. The initial misunderstanding stems from the fact that gods and rulers, possibly only after their death, appear in the same context, especially as owners of buildings.

Hypothetical story based on written sources

Sylvanus Griswold Morley developed a time scheme based on a literal adoption of the statements of (certain) Chilam Balam texts. Due to the calendar correlation used, the times are sometimes around 256 years too late.

| 948 | The Itzá leave Chakán Putum and move to the northern Yucatán |

| 987 | Repopulation of Chichén Itza by the Itzá, dominance of Chichén Itza in the northern Yucatán |

| 1224 | Conquest of Chichén Itza by Hunac Ceel , the Itzá are expelled, the Cocom dominated the Yucatán from Ich Paa |

| 1441 | Ah Xupan Xiu leads the uprising as a result of which Ich Paa was destroyed, almost all of the Cocom members are killed |

In the 1950s, Alfred M. Tozzer in particular tried to interpret the statements of the sources more reliably against the background of the archaeological results available at the time. Although this reconstruction is viewed critically today, it can be found in many general representations.

The settlement (the Chilam Balam texts speak of the "discovery") is set to 692 (Chilam Balam of Tizimin), 711 or 731 (two sections in the Chilam Balam of Chumayel), according to the Codex Pérez to the period between 475 and 514, however, Tozzer does not consider any of these dates to be historical. The colonial sources also speak of a Great Descent (from the East) and a Small Descent (from the West), where the size refers to the number of people. There is even a long list of places (in Chumayel) for the big descend, starting with the port of Polé on the east coast.

Several texts refer to an obscure event involving a person named Hunac Ceel, which can perhaps be dated to 1194. According to the Codex Pérez, the head of Chichén Itzá, Chac Xib Chac, was expelled because of the deviousness of Huac Ceel, ruler of Mayapan. He was driven out by several people with Náhuatl -like names. This eviction was connected with a banquet given by Ulil the lord of Izamal . The strangers were later called Cupul , and they were met by Francisco de Montejo during the Spanish conquest at Chichén Itza. The story is portrayed somewhat differently in the Tizimin text: Chac Xib Chac was invited to the wedding feast of Ah Ulil von Izamal, as was Hunac Ceel. His underhandedness consisted of the fact that he gave the Chac Xib Chac a love charm to smell, whereupon he desired the bride of Ah Ulil. The war broke out and Chac Xib Chac was expelled from Chichén Itzá.

At some point, Landa says, between 1224 and 1444 a Kukulcán arrived with the Itzá in Chichén Itzá, and a little later founded Mayapan.

Hunac Ceel was later thrown into the sacred cenote of Chichén Itzá, but he survived and came back with the prophecies and became chief chief. The ruler was Ah Mex Cuc. In 1461 Chichén Itzá came to an end, some of its residents moved to the island town of Tayasal in the far south of Lake Petén, where they were able to maintain their independence until March 13, 1697.

A later view sees the Itzá as a group of immigrants who came from a more Mexican-influenced area. They reached Yucatán in the aforementioned Little Descent from the West. It is said of them, among other things, that they had only a broken command of the Maya language. As their leader appears Kukulcán (whom the older research connected with Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl from Tula with the same name in Náhuatl ), who is said to have left his country in the direction of the Gulf of Mexico. This is put in the year 987. However, historical analysis of the historical information cannot clarify what role (if any) Toltec immigrants, warriors or religious leaders played in Chichén Itzá.

Structure and infrastructure

According to the official archaeological delimitation, the area of Chichén Itzá covers around 15 square kilometers and extends to the outskirts of the small town of Pisté in the west. The density of development in this area is uneven: Areas with buildings made of stone masonry of different construction techniques that were relatively close together were on platforms that were more or less elevated above the surrounding area, some of which were surrounded by low walls. These are always surrounded by zones that are virtually undeveloped. They will have been used for cultivation to supply the population, but this cannot be proven in detail.

The level platforms with a stucco surface were the primary traffic areas within each group. For the connection between the built-up areas and the center, more than 70 sacbeob , stone streets, have been verified in Chichén Itza .

The numerous funnel-shaped collapse dolines (known locally as “rejolladas”), which did not reach the groundwater level, were particularly important. Because of the sheltered location and the special temperature conditions, plants (such as cocoa ) could be grown in them that would not thrive on the more or less flat terrain, as is still the case today.

The water supply was based mainly on the two water-bearing sinkholes (the "Holy Cenote", which may not have been used for secular water supply, and the Xtoloc located near the center) and on a few cisterns (chultun). In a collapse doline near the Chichen Viejo group , a broad masonry well from ancient times was archaeologically uncovered, which should have ensured the water supply in the area.

Chichén Itzá architecture

Despite attempts to reconstruct a story, Chichén Itzá is mainly famous for its architecture. The different building types and styles are still one of the most important sources of information about the history of the place. Here, different types of buildings catch the eye, which can be distinguished according to their floor plan. In addition, there are construction details and shapes and techniques of the facade decoration that are characteristic of the respective building type. The distinction between buildings in three successive phases, namely Maya, Toltec and Maya-Toltec, introduced by the researchers at the Carnegie Institution based on these criteria, is no longer maintained today. The function of many buildings has only been partially clarified.

As examples of building types, only well-preserved and mostly restored buildings are mentioned here (numerous others are hidden in the dense forest and not exposed):

- Pyramid buildings with stairs on one or four sides, at the top temple buildings partly with a hall-like interior. Examples: Castillo, Osario. The function was mainly religious.

- Temple with hall-like interior on a multi-level high platform. Examples: Warrior Temple (Templo de los Guerreros), the two temples of the large and small sacrificial table, Templo de la Fecha.

- Ball courts. Examples: large ball playground, ball playground east of Casa Colorada, ball playgrounds in the thousand-column complex. The symbolic function of the ball game is controversial.

- Porticoes. Example: Numerous columned halls in a thousand-column complex. Function: According to the relief representations, they served the gathering of large numbers of people of equal rank, especially the warriors.

- Courtyard galleries with courtyard with colonnade and portico. Example: Mercado, more, etc. a. in the Grupo de la Fecha. Function uncertain.

- Buildings with rows of interiors, according to the Puuc tradition. The rooms are arranged in one or two parallel rows, transverse rooms at the ends are common. Example: Casa Colorada, Casa del Venado, Akab Dzib, Las Monjas, Temple of the Three Lintels. Function: administrative center or official residence of a noble line.

- Buildings with numerous interiors with complex floor plans and enclosed courtyards. Example: Casa de los Caracoles in the Grupo de la Fecha, buildings immediately east of the Monjas. Function: Official residence of a noble line.

- Low square platforms with four flights of stairs. Example: Platform of the eagles and jaguars and Venus platform, platform in front of the Osario. A ritual function is to be assumed.

- Large platforms with surrounding low walls and gateways. Example: Large platform, Grupo de la Fecha. The function of the walling is not military, but serves to demarcate zones that were not or only partially accessible to the public.

- Sacbes (brick streets) connecting the different groups of buildings, about 70 have been located so far. Function: As vehicles were not known and could not have been used because of the interposed stairs, the streets were used for processions and symbolically expressed relationships between the connected zones.

Some of the buildings have names from colonial times, but most are of more recent origin and describe a distinctive architectural feature. German names are only given here if they are established. Most buildings, however, do not have such a name, many are only designated with the quadrant (according to the map of the Carnegie institution) and in these with a serial number.

The big platform

Only a small part of Chichén Itzá is accessible to tourists, where most of the buildings have been excavated and partially reconstructed. This part lies on a large terraced area and is surrounded by a wall that has been erected again in individual places (for example at the beginning of the path to the sacred cenote). The different parts of Chichén Itzá were connected by stone paths, sacbé .

El Castillo

In the center of the temple complexes of Chichén Itzá is the large step pyramid known as Castillo ( Spanish for “the castle”) . The thirty meter high structure has four staircases on all sides for access. It is speculated that the length of the Mayan year is coded in the steps: if all four side staircases had 91 steps (the ones that exist today are the result of reconstructions, so this number is not certain; besides, the terrain is not completely flat, which is why the stairs should actually have been of unequal length), this multiplied by four (number of stairs on four sides of the pyramid) and the step in front of the temple - actually the base of the building - is added, this would result in the number of days in the year of the Maya.

The side surfaces of the pyramid on both sides of the stairs are 9-fold. The (almost) vertical side surfaces of the steps are connected at the top by a horizontal band, the larger part consists of a pattern of four rectangular surfaces that appear to be hanging down over a smooth outer surface of the steps that is slightly set back. The rectangular areas get smaller from step to step for reasons of space, the number of the last two steps is also reduced. The corners of the steps are slightly rounded.

The top of the castillo bears the temple of Kukulcán , the Maya snake deity, whose name corresponds to the Toltec Quetzalcoatl . The six meter high temple on top of the pyramid has a main entrance to the north supported by two serpentine columns. This leads into a narrow room that takes up the entire width of the square temple, from which one reaches the central room, the roof of which is supported by two pillars. An aisle-like room runs around this central space on three sides, to which entrances lead from the remaining three sides. The door reveals show Toltec warriors in bas-relief.

Inside the pyramid there is another, smaller (side length about half of the later) pyramid, which also has nine steps. However, it has only one staircase on the north side, which is accessible through a short tunnel dug by archaeologists from the side of the later staircase (closed to visitors). The earlier temple is more simply designed than the later one. It only has two rooms of the same size, one behind the other, of which the rear one can be entered through the front one. There the explorers found a stone jaguar that was painted red and designed as a seat with jade eyes and may have once served as a throne. The upper facade of this temple has been partially exposed and shows dominating jaguars in procession.

The Castillo is the undisputed crowd puller in Chichén Itzá. It has this rank not only because of its impressive construction and size, but also for another reason: Twice a year, at the equinox and some time before and after, one side of the pyramid sinks almost completely into shadow at sunset. Then only the stairs are illuminated by the sun and the steps of the pyramid are projected onto them. This band of light finally unites for a short time with a snake's head at the foot of the pyramid and thus represents a feathered snake. It is not provable that this impressive effect was interpreted in the same way by the Maya and even less that it was when the Pyramid was intended is part of the opinions. Other sources say that the effect was calculated.

The same applies to an echo with which tour guides tend to impress tourists: If you stand in front of one side of the pyramid, the sound is thrown back many hundreds of meters and amplified. Clapping hands sounds like a pistol shot. The echo inevitably arises with a sufficiently large smooth reflection surface.

Templo de los Guerreros - The warrior temple

The so-called warrior temple because of its reliefs (which can also be found in other places in Chichén Itzá) is a construction that dominates the large platform on its east side. The building consists of a pyramid base with four steps and a large upper surface, about half of which is taken up by the actual temple building. This is moved all the way to the rear edge, so that a larger free space is created in front of it.

The top platform of the temple can be reached via a staircase that was originally reached from the pillared hall in front of the temple pyramid . Two slightly elevated pillars and wall approaches on the sides show that the roof of the columned hall reached a little higher up the stairs. The stairs are closed to visitors. The outer walls of the pyramid-like substructure are adorned with continuously repeating relief representations, they show eagles, jaguars and, between them, warriors in a semi-recumbent posture. Their costume is typically Toltec: the large horizontal nasal stake, the glasses-like jewelry in front of the eyes, the knee bands and sandals tied with large bows, as well as the spear thrower.

In the open space in front of the actual temple, one of the figures known as Chak Mo'ol stands in the characteristic half-lying pose. The name chacmool passes to the New York amateur archaeologists Augustus Le Plongeon from the second half of the 19th century, which saw the image of a suspected him of Mayan prince in him, he has nothing to do with the rain god Chac do .

The roof of the halls and the temple interior carried pillars made of square stone blocks. They depict warriors as well as eagles that devour human hearts. The entrance to the temple interior was supported by two feathered serpentine pillars. The protruding parts of the tail held the monumental wooden door beam. These snake pillars are largely identical in Tula and are therefore regarded as Toltec.

Inside the temple area, several rows of square pillars with reliefs on all sides supported the vaulted roof, nothing of which has survived. On the back wall is a low table made of stone slabs, which is held by several dwarf-like atlantic figures on their heads and arms. The outer wall of the temple mostly has cascades of masks of the rain god Chac at the corners. In the wall surfaces, large fields are filled with a flat relief of feather tendrils, in the middle of which the human-bird hybrid, also known from Tula, protrudes fully from the wall.

On the north side of the pyramidal substructure is an access created by archaeologists to the earlier construction phase of the temple (sometimes referred to as the temple of Chak Mo'ol), the structure of which largely corresponds to the later one, but is slightly shifted to the north. For the construction of the later temple, it was filled with rubble to support the weight of the new building. The pillars of the earlier temple, which once supported the roof that was removed when the later temple was built, are decorated with reliefs, similar to those of the later temple. It was uncovered during excavations in the 1930s. The colored painting of the relief pillars is still completely preserved here because the interior was completely filled with rubble during the construction of the later temple and was therefore preserved. It shows how all the pillars must have looked originally.

In front of and along the south wall of the temple pyramid runs a magnificent portico that extends further to the east and surrounds a large courtyard on three sides. It is considered part of the Grupo de las Mil Columnas, "Hall of 1000 Columns" (see below).

- Templo de los Guerreros (Warrior Temple)

Templo de las Mesas - Temple of the great sacrificial table

To the north of the warrior temple is a temple excavated in the 1990s (first excavation attempts go back to Teoberto Maler , who also coined the German name), which is very similar to the warrior temple in its shape including its temple building, but somewhat smaller. An earlier temple building with well-preserved, colorfully painted relief pillars was also found inside this pyramid base, which is not accessible. There is no colonnade in front of the temple, it extends in smaller dimensions to the north at its side.

Juego de pelota - The large ball playground

At least twelve ball courts have been found in Chichén Itzá. The juego de pelota on the large platform is the largest and most important of more than 520 ball courts of the Mayan culture. It is located about a hundred meters northwest of the pyramid of Kukulcán. The playing field is 168 m long and 38 m wide. The shape of the playing surface is reminiscent of two “T” placed one against the other, it is flanked by eight meter high walls from which the ball bounced back into the playing field. The walls are unusually thick. From the outside, almost the entire length of the stairs led to the surface of the walls; they have not been reconstructed. Because of the limited space on the walls, the ball game could only be watched by a limited number of people. The walls were preceded by a wide plinth over the entire length and slightly beyond, the front edge of which was bevelled. Long relief scenes are attached here in 6 places.

The “Great Ball Court” in Chichén Itzá was (due to its size and the height of the target ring) hardly really usable for ball games, but rather intended for ceremonial purposes and probably served to represent political and probably also religious power.

When playing ball , the ball had to be played without the help of the hands and legs; only shoulders, chest and hips were allowed. The ball was made of rubber, was massive and weighed about 3 to 4 kg. The images show the protective clothing worn by the players. It was made of hardened leather, and wooden reinforcements were also attached. In addition, some of the players wore two different shoes. One of them had protection for the ankle so that the player would not injure himself when throwing the ball to the ground (to reach the ball running on the floor with his hip). An iron-shaped object made of wood served as support and protection for the hands. Colonial reports about the Aztecs show that a game seldom ended without major injuries; bruises in particular were extensive and treated surgically.

The object of the game in its late classical and post-classical versions was to shoot the ball through one of the two rings attached to the reflex walls. Since the openings were not much larger than the ball, this would only rarely have been possible. In the case of the “Great Ball Court” in Chichén Itzá, the height at which the rings were attached was another problem.

Many of the ball courts in Chichén Itza have reliefs. The ones at the “Great Ball Court”, which are repeated six times, show that someone was beheaded. The blood pouring out of the body of the beheaded is represented in the form of seven snakes, which the Mayans regarded as a symbol of fertility. The “tree of life” grows out of the blood that flows on the ground. This representation is based on a myth of the Mayans, which describes the origin of the game. According to the current state of knowledge, the representation does not allow any conclusions to be drawn as to whether winners or losers lost their heads, or whether the representations should not be understood more symbolically.

Many details of the ball game are no longer known today, some are inferred from analogies with the better known conditions among the Aztecs. Because of this lack, there are many nonsensical ideas about the ball game. For example, tour guides in Chichén Itzá demonstrate that if you clap your hands somewhere in the square, you get multiple echoes, which is inevitable with large flat areas. It springs from the imagination of the tour guides that the reason for this echo is the construction of the side walls made of seven different types of limestone and sandstone, because the building material is basically uniform and sandstone is nowhere to be found in the Yucatan. In addition, the material of the surfaces has no effect on echo effects.

Temple at the ball court

The religious and symbolic importance of the large ball playground is underlined by the temples located within its walls.

Temple of the Jaguars

The most important and striking is the temple of the jaguars, which stands on the southern end of the eastern side wall of the ball court, which is expanded at this point to a pyramid base. Only a narrow side staircase leads up to the temple (closed today). The temple is oriented towards the inside of the ball court. The entire construction shows the Maya's struggle with the cramped space conditions for the temple: The building platform that supports the temple is only a little smaller than the base of the pyramid. As a result, only a narrow strip of flat space remains in front of the building platform. This strip stands in strange contrast to the access stairs, which take up almost the entire width of the temple.

Access to the interior of the temple is through a wide entrance supported by two extremely thick serpentine pillars. The tongues of the snakes protrude far from their mouths. The vertically standing serpent's body is bent twice forwards and then upwards and surrounds the door beam with the snake rattle. The temple has two parallel rooms one behind the other. Its walls are now heavily faded with murals. Early copies show battles between large numbers of warriors on the outskirts of a village, where people still seem to go about their daily activities undisturbed.

The design of the facade is the most complex and richest in Chichén Itzá: the lower wall surface, which consists of several recessed fields, in which there is no decoration, follows on a sloping base. This is followed from bottom to top by four broad bands with the following motifs: The bottom band is smooth, the one above and the fourth shows two intertwined feathered snakes. Most impressive is the third band, which depicts a continuous procession of jaguars. Between every two jaguars there is an image of a shield, the feather curtain of which falls over the two lower bands. Towards the top, after a smooth band, there is a zone with angular coiled feather snakes. Between the windings there are three concentric discs in the lower row and three hourglass-shaped columns in the upper groups. Above that follow for the third time the intertwined snakes of feathers. The facade, which reaches a height of eight meters, is closed at the top by the usual large, slightly inclined stone slabs.

The entrance side of the temple has been reconstructed, only the base of the wall and the lower parts of the serpent pillars were in situ.

- Views of the Jaguar Temple

Lower temple of the Jaguar temple

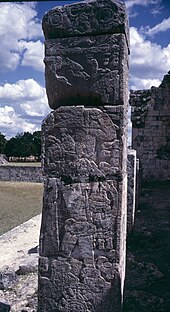

The lower temple of the Jaguar Temple consists of a rectangular room. It stands below the jaguar temple on the outer wall of the pyramid base. The entrance is formed by two pillars and therefore has three openings. The pillars and the side wall pieces next to the passageways have bas-reliefs . There is a jaguar throne in the middle entrance .

This temple (like the north temple) also has a bas-relief covering all the walls in several registers, which was originally painted in color (remains are still preserved in the corners). The painting for better recognition with a red background is modern (by the archaeologist Erosa Peniche). The content of the relief evidently shows historically thought scenes in which important, magnificently dressed individuals are connected with hieroglyphic symbols that do not belong to the canon of Mayan script.

The facade design is a combination of the Puuc style (upper half of the wall with three-fold horizontal bands) and the sloping lower part of the lower wall surfaces, as they are characteristic in central Mexico. The front part of the vault and the corresponding facade have been reconstructed.

North Temple

The North Temple, also known as the Temple of the Bearded, is a small building on the northern wall of the ball court. It consists of a single room, to which an entrance with two pillars leads. The stringers of the access staircase show a tree, the roots of which emerge from the earth monster. The interior walls of the room, including the only partially preserved vault, are decorated with a roughly executed bas-relief similar to that of the lower temple of the jaguars. Here, too, the colored contouring is modern.

South temple

The south temple is actually a single 25 meter long room that is open to the ball playground with a row of 6 sculpted pillars. The pillars show the usual theme of warriors in Toltec warrior gear, who stand on the depiction of a bird man. The figures are identified by characters that are outside the hieroglyphic tradition of the Maya. The building is poorly preserved, the side walls have been partially reconstructed.

Tzompantli

Not far from the eastern side of the Great Ball Court is a platform that was given the Náhuatl term Tzompantli in modern times because of its decoration in bas-relief . This word designates platforms on which a wooden frame was erected, to which the skulls of sacrificed people were attached, as it has been described in detail for Tenochtitlán and depicted at the time.

The Tzompantli of Chichén Itzá is a large platform a little over 1.5 meters high with a T-shaped floor plan. The vertical outer walls of the platform are covered in three registers with four rows of skulls, with the wooden posts also shown. The square part protruding to the east from the building block of the actual Tzompantli is similar in many details to the two platforms described below. The central motif of the décor here shows a sequence of warriors between eagles, which are represented as oversized and hold human hearts in their claws in order to devour them. In the two frieze bands an uninterrupted sequence of relatively short snakes is shown, while the top band shows large feather snakes whose heads protrude fully at the corners.

Venus platform

The Venus platform is located north not far from the great pyramid. Like the platform of eagles and jaguars, the construction consists of a block of wall with a square base, to which stairs lead up in the middle of all four sides.

The bas-relief, visible in raised and recessed fields on the side surfaces, depicts, among other things, the human-bird hybrid being en face . In addition, there is the symbol of the planet Venus, tied to a bundle of rods, from which the so-called Mixtec symbol of the year stands out as a reference to a calendar function can be recognized. The stairs of the platform are flanked by one of the snakeheads. These snake heads are the plastic ends of a band of snake bodies that are drawn around the platform in the uppermost register. A platform with an almost identical image program is located immediately east of the Osario.

Platform of eagles and jaguars

The smaller of the two structurally identical platforms is located directly on the southeast corner of the Tzompantli. The themes of the bas-reliefs are similar, but not the same, the depictions of the Venus sign are missing. Instead, eagles and jaguars are repeatedly depicted holding human hearts to eat them. Eagles and jaguars were names for warrior associations among the peoples of Central Mexico. One can assume that the same ideas existed behind the depictions on the Toltec-inspired buildings in Chichén Itzá. The stairs on the four sides end at the top in fully plastic snake heads, the snake body covered with feathers is indicated in a very flat relief on the stair stringers.

The great wall

The path to the Cenote Sagrade cuts through the wall that surrounds the northern district, which is very high compared to the surrounding area due to the height of the platform. Columns were discovered on the inside of the wall when entering the cenote, which may have supported a roof leaning against the wall. The function is unclear, it has been assumed that they were market stalls. The wall is broken through at eight places by a gate construction that ends on a sacbe leading to the outside .

Cenote Sagrado - the sacred "well"

About four hundred meters to the north of the pyramid of Kukulcán is the impressive Cenote Sagrado, in English the “sacred sinkhole ” (natural “well”) with an almost circular shape and vertical walls. Chichén Itza takes its name from him, namely fountain of the Itzá. Here, Edward H. Thompson made from 1904 to 1910 underwater investigations. More recent investigations took place around 1960, which brought many thousands of finds to light. Large quantities of objects were found on its land, including jewelry, jade , gold and various ceramics. In addition, over fifty skeletons were found. According to the report from the 16th century, known under the name of the Bishop of Yucatán Diego de Landa, these are interpreted as human sacrifice, which is also supported by the entire constellation of finds. At the edge of the sinkhole is a small temple building.

Group of a thousand pillars

To the south and east of the warrior temple runs a colonnaded hall originally covered with Mayan vaults. It collapsed everywhere because the wooden beams that spanned the spaces between the pillars had rotten. The pillars that originally supported the roof are made of square stone blocks and are mostly sculpted on all sides. They show warriors in Toltec costume and equipment, and in the lower and upper registers depictions of snakes and bird men. A stone bench runs along the back walls of the former columned halls, which is interrupted at various points by a slightly raised and protruding platform, the outer wall of which is decorated with bas-reliefs of a warrior procession. The portico are divided into four arms:

- West arm, south of the warrior temple. At the southern end, the western arm bends west and leads to a small temple.

- East arm. It begins immediately south of the warrior temple and runs east from there until it comes to the edge of a karst doline. There are various buildings with smaller porticoed halls.

- South arm. Not really a continuous columned hall, but smaller sections of halls that are in front of other buildings. They start at the end of the eastern arm and run south.

- North arm. This is the portico that is in front of the warrior temple and a portico north of the Templo de las Mesas, they are oriented north-south.

It is noticeable that columned halls of this density and size cannot be found anywhere else in Chichén Itzá. The spatial organization and the image program on the masonry platforms and the sides of the pillars indicate the function of the halls. Because there was a lot of space of the same symbolic quality in them, large numbers of people of largely equal rank gathered in the halls. The representations of rows of warriors on the raised platforms identify those gathered as warriors.

The themes on the pillars, namely warriors and the hybrid bird-human being, confirm this assignment and give an ideological reference. Similar (smaller) halls are also known from Tula and the main temple district of Tenochtitlán .

Palacio de las Columnas Esculpidas

The building is located in the northern part of the southern arm of the Thousand Columns. A two-row columned hall is in front of it in the west. This building (technical nomenclature 3D5) has undergone several redesigns. Originally it consisted of two rows of rooms at right angles to each other. The facade is unusually well preserved because the first building was walled on on all sides at a later date in order to build a small temple on a higher level, to which a staircase led up from the east (i.e. not from the Courtyard of the Thousand Columns). For the columned hall to the west, the front row of rooms was torn down and the remains were filled with stone masonry.

The facade of this early building is characterized by a high beveled plinth, a smooth lower wall surface and a central frieze band made up of three sections, with the middle one having a continuous decoration. Snake heads protrude from it at greater distances. The upper facade surface shows masks (in the form of two-part cascades) and in between fields with either three rosettes one above the other or one large rosette. The upper cornice also consisted of three bands, of which the middle one was decorated in bas-relief.

The building is a good example of a Chichén Itzá style of architecture that is earlier than what was known as Toltec and has ties to the Puuc style.

To the east is a long hall (3D6), which is formed by six rows of square pillars. At a later time, intermediate walls were drawn in between the pillars at the eastern end, either to ensure greater stability or to separate a small space.

To the south of this building is the actual palace of sculpted columns. The building is somewhat complex: facing the courtyard is a portico consisting of two rows of sculpted columns all around. In the middle there is an entrance into a narrow room, the access is to a rectangular room behind it with two rows of columns. From there you can reach square rooms with nine columns in both the south and north.

Templo de las Mesitas - Temple of the Small Sacrificial Table

To the south of the building just described is this previously unexcavated and restored temple (3D8), the first description of which (and the German name) goes back to Teobert Maler. Structurally, the building is very similar to the warrior temple and the temple of the great sacrificial table.

Here, too, there are two rooms, one behind the other, on a raised platform with a central staircase on the west side. The roof was supported by sculpted pillars. Here, too, the entrance was formed by two monumental pillars in the shape of a snake.

In the row of buildings on the eastern side of the courtyard, there are several buildings that have not yet been excavated. 3D9 has a pillared hall, behind which there is a two-room temple structure. Building 3D10 consists of several connected porticoed halls with a considerable internal area. Numerous walls were drawn in between the columns.

Small buildings behind the east colonnade

Behind the buildings described here lie several smaller constructions. The unusually large and lavishly built sweat bath (Temazcal) is particularly important , as several smaller sweat baths in the courtyard of the Thousand Pillars are tiny in comparison. The building has a small portico made up of four columns with benches on the back wall at different heights. From there, a low hatch leads into the actual sweat bath, a rectangular room with a low stone vault and a niche on the back.

To the north of the sweat bath is a medium-sized ball playground (3E2), of which only the side walls of the reflective surfaces have been exposed. They show warriors or ball players with large feather headdresses in a poorly executed bas-relief that was previously over-modeled with stucco.

Mercado - the "market"

The falsely so-called market of the temple city of Chichén Itzá is an example of courtyard galleries that emerged after the heyday of the Maya. The building consists of a long portico in an east-west direction, which can be reached via a staircase from the open area in front of it. The back wall of the portico is lined with a brick bench, which is interrupted by protruding “throne seats” with sculpted sides (depictions of warriors in processions).

The portico was covered with the Mayan vault that rested on wooden beams. In the middle of the rear wall, a wide doorway, the sides of which also show depictions of warriors, leads into the square courtyard. This was surrounded on all four sides by a high outer wall. A series of pillars ran parallel to the outer wall, on which a wooden roof structure was supported, extending from the outer wall. The interior of the courtyard was somewhat deepened and not roofed over. The function of the courtyard galleries and thus also that of the “market” has not been clarified.

The group of the high priest's tomb

This group lies outside the perimeter wall of the great platform and the group of the Thousand Columns, and is connected to the former by a brick path that started from a gate opening in the perimeter wall.

Osario - high priest's tomb

At the edge of the central area of Chichén Itzá stands the so-called grave of the high priest. The fanciful name goes back to the American diplomat and archaeologist Edward H. Thompson , who undertook the first excavations and discovered a deep vertical shaft inside, which led to a grave in a natural cave below the terrain level. In the 1990s, the pyramid and the temple area were excavated and reconstructed under the direction of Peter J. Schmidt.

The Osario is a four-sided pyramid whose structure corresponds to the Castillo with stepped outer walls and stairs on the four sides that end in snake heads at the bottom. The stair stringers are designed as a serpent's body. The almost vertical surfaces of the seven pyramid levels show one or two elongated recessed fields, in each of which two fantastic birds with human decorations face each other in bas-relief.

The temple area is more like that of the warrior temple with stone pillars in relief and a sacrificial table carried by dwarf-like atlases. The entrance is formed by two large columns in the shape of erect snakes. Two of the stone pillars in the temple area bear inscriptions that also contain dates, corresponding to February 5 and May 12, 998 AD (converted to the Gregorian calendar).

The outer facade of the temple is in the Puuc style, but for the most part no longer preserved in place. From the rubble, unusually high cascades of four masks could be reconstructed for the corners of the temple area.

Buildings near the Osario

In front of the pyramid in an easterly direction there are three smaller constructions on a line which then continues in a sacbé that leads to the small Xtoloc temple: a round platform, a platform in which brick graves were found. In the middle is the (southern) Venus platform, which has the almost identical image program (and therefore probably also the function) of the northern Venus platform. Here, too, the bird-people appear en face , looking out of a deepened field, and on their side stands the tied bundle of sticks, crowned by the Mixtec year bearer symbol. Next to it the great sign of Venus. However, the quality of the reliefs is far worse than those on the large platform.

Xtoloc temple

Of the three small constructions described, a sacbé, which has partially collapsed and reconstructed because of cavities underneath, leads to the small Xtoloc temple, which stands on the edge of the cenote of the same name . This temple has an entrance supported by four columns, which leads to a long, rectangular portico with six columns. Two steps higher is the entrance made of two square, sculptured pillars. The quality of the relief is unusually poor, both in the drawing and in the execution. The entrance leads to a small room, from which a narrow door in the middle gives access to a small chamber behind it with a high stone bench. This floor plan is a modification of a type common to small temples in Chichén Itza.

Casa Colorada - Red House

Not far from the high priest's grave lies the Red House (Casa Colorada) on a high plinth with a wide central staircase , which got its name from the red painting on its interior, which has been preserved in small remnants. A long ribbon with hieroglyphic inscriptions runs in the front room over the entrances to the rear rooms. The building also bears the Mayan name Chichánchob (small openings), which can be seen in the facade. The temple has three entrances on the front side, the facade is designed simply and is structured by two overlying cornices and decorated battlements. The building is dated to around 850 AD and is one of the oldest buildings in Chichén Itzá.

At the rear of the building, a ball playground was later added to the high base. The ball playground visible today is a later overbuilding of an earlier similar but smaller construction. On the eastern side of the ball court there is a badly damaged building with a portico entrance. The restoration took place in 2009 and 2010.

Casa del Venado - House of the Deer

Next to the Casa Colorada , also on a high terrace with a monumental staircase, is the similarly designed Deer House (Casa del Venado). It also had three entrances on the front, of which the right and the corresponding part of the room behind and the right rear room collapsed. The facade was smooth, only in the uppermost part were decorations of a roof ridge, which are difficult to see due to the destruction.

The southern group or group of Las Monjas

Without any clear demarcation, the southern group, which consists of numerous buildings, connects to the south. The Caracol and the large Las Monjas building with numerous buildings on the east side are outstanding .

Caracol - The snail tower

The Caracol is an observatory in its final expansion phase. The name Caracol refers to the winding, narrow staircase inside that leads to the upper structure of the building (span: escalera de caracol = spiral staircase). The building, which was excavated and restored in the 1930s under the direction of Karl Ruppert , was erected in several construction phases and was given its final shape with the characteristic structure late. At the beginning a large, rectangular platform with rounded corners was created, to which the preserved staircase on its west side led up. The stair stringers are adorned with the intertwined bodies of snakes and end in a serpent's head that protrudes over the stairs. During the excavations, around 60 incense burners in the form of human heads were recovered from the rubble, which were probably originally placed on the edge of the platform.

On top of this first platform, another, circular 11 meters in diameter was built. Another, higher, circular platform with a diameter of 16 meters was then built around it. Then there was an extension and elevation on the west side, which was then added on the east side. Both together resulted in a not completely rectangular shape with a side length of about 24 meters. This includes a staircase on the west side, also with intertwined snakes. A stele with 132 hieroglyphic blocks was found in a niche in this staircase, the date of which is not certain.

The round tower was finally erected on the surface of the last platform. It consists of two concentric aisle-shaped rooms that are covered with Mayan vaults. There are four entrances to the outer and inner corridors, but they are offset from one another. In the center of the second circular corridor there is a round block of wall, which has a low and narrow doorway at a height of about three meters, from which a very narrow and difficult to pass winding staircase leads up to the observation room on the roof level.

The upper structure, which contained an observation chamber, had several deep and narrow window openings to the outside. By sighting diagonally over the inner and outer edges of the windows, positions on the horizon could be observed with sufficient precision. The three window openings obtained provide the orientations given below. Other interpretations have also been suggested.

|

|

The lower wall surface of the building is smooth, but at 3.3 meters it is unusually high. The frieze consists of five simple elements. Above it rises the largely destroyed upper wall surface, which had one of the typical masks above each of the four entrances, as well as a seated figure. The building is built in the Puuc style.

A round stone disc also comes from the Caracol , showing a ceremonial act in two registers: In the upper half, three men stand in front of a lavishly dressed seated person, and two other people behind him. In the lower half, three men face two others, the two in the middle appearing to be shaking hands. At the edge of the scene birds can be seen above and two dogs below.

- Caracol - snail tower

Las Monjas

The Las Monjas building is on a platform that it shares with the Caracol and numerous smaller buildings. It has undergone a large number of structural changes, making it one of the most complex in Chichén Itzá. A very extensive excavation by the Carnegie Institution of Washington took place in 1933 and 1934 under the direction of John S. Bolles.

The building seems to consist of two parts that do not belong together: the eastern part, which is usually referred to as the annex , and a high platform with a staircase in front from the north, which leads to a building on the second floor, above which the remains of another floor are visible with the staircase in front.

The actual building history is different: In the beginning there was a simple platform with rounded corners, a little over two meters high, with a protruding staircase from the south. This platform is only visible today in the large opening in the western part of the complex that was created by the collapse. This platform was then raised to about twice the size and a one-room building with three north-facing gateways was built on its surface. The wing, which is known as the annex, has now been built to the south of the platform. It originally consisted of 13 rooms, made up of three parallel rows and a final, transverse room in the east. The middle row of rooms could be entered from the rooms in the south. The end room had passages to the adjoining rooms of the outer rooms, as well as a small side entrance to the outside.

The room layout with the end room and the facade decor make it clear that the focus of the building had shifted to the courtyard to the east. While the lower wall surface of the north and south facades are kept simple, with fields of different widths with cross stones forming the only decoration between the doors, the corner of the building and the entire facade in the east are fully decorated. The upper wall surface of the north and south sides have differently designed Chaak masks, as well as fields with diagonally placed saw stones and rosettes. The friezes on these pages are also kept relatively simple.

The image program on the display side around the eastern entrance combines motifs from the entire northern Maya area: the teeth of a snake-mouth entrance are arranged around the entrance door. But it's just an eclectic quote - for a complete snake mouth, the eyes are missing over the door and the noses and nasal stake are missing on the sides. In their place, flat Chaak masks are arranged in a double cascade. The identical masks can also be found on the upper wall surface. The same corner-shaped masks appear at the corners, so a total of 12 masks can be seen on this side. This type of ornament is a very vivid example of the Chenes style . The interior of the building is also decorated with Chaak motifs. Above the door sits the figure of a ruler with a large feather headdress in an oval frame from which square volutes emerge. It may be the ruler who was immortalized in this building on seven stone door beams under the date of February 8, 880.

The building rests on an unusually high base, which is closed off by a simple feather-shaped cornice. The middle strip of cornice, which jumps up over it in an angular shape to leave space for the pseudo-snake-mouth entrance, has five horizontal bands: a braided band, a band that reproduces a differently designed braided band, a smooth element, and one above Row of ik characters that appear to be hanging from another smooth, narrow ribbon. The upper frieze has only four elements: two smooth protruding ones that frame a recessed field with inclined saw stones, and above that the usual diagonally protruding end stones, in which another braided motif is inserted at intervals, reminiscent of the Mixtec year bearer symbol.

If the mentioned dates of the year 880 indicate the completion of this wing, then in the beginning of the 10th century the high platform was extended so that a wide platform was created in front of the building. This extension covered the three western rooms of the building on the ground floor, which for this purpose were either largely demolished or filled with rubble masonry. However, this extended platform did not leave enough space for an extension of the building on the first floor, which made it necessary to enlarge the platform again. The next three rooms (seen from the east) that came to lie under the platform were lost. For structural reasons, they too were filled with rubble. The top platform, which was now clearly visible on the outside, was provided all around with alternating stone mosaic decoration.

This provided the prerequisites for the final design of the upper part of the building: the originally single-room building was expanded to eight rooms, six of which were parallel to each other (a large, central one with three entrances and two smaller rooms on the sides), while the eastern and there was a transverse space at each western end. The facade shows large, slightly recessed fields with diagonally set saw stones on the narrow sides and with four meandering steps on the long sides. The upper wall surface slopes slightly inwards. A staircase was put in front of the north facade, which led to a small building on the next level. The staircase does not jump over the facade with a Mayan vault, but with a flat ceiling made of stone blocks. The top building was unadorned and had only one room, whereas relief ornaments can be found on the last steps.

In an unclear connection with the expansion of the high platforms, the remaining two interior rooms were also filled with rubble, with parts of the vault being removed. However, as an extension of the entrances to the central rooms, narrow, blind-ending corridors were left free, which later became points of attack for robbery graves.

Iglesia - The "Church"

The so-called Iglesia ("Church") is located in the immediate vicinity of the Las Monjas building. It is a very small building with only one room and a single entrance from the east. The design of the facade shows a clear contrast between the lower wall surfaces, which consist of little worked stones in irregular rows, and the stone mosaic above. It seems that a kind of curtain made of cloth has been used here instead of the usual stone cladding, because there are numerous holes on the lower edge of the central cornice that served to fix it. This is a form of variable facade design that is otherwise not known in the Maya area.

The lower cornice has five horizontal bands, the middle of which consists of a step band worked in relief. The cornice goes around the whole building. The wall surface above shows three large Chaak masks on the front side (two of them at the corners), between which two sitting animal-human figures can be seen in two small square niches. They represent (from north to south) an armadillo, a snail, a turtle and a crab. Their bodies are set deep into the wall with pegs. The heads, which were fully sculpted, were cut off in all cases. They are interpreted as figures of the Bacabs, mythical figures who carry the sky.

On the back of the building there are also three masks, between which flat meander motifs are inserted, which are also found identically on the narrow sides. The upper cornice also stretches identically around the whole building and consists of four bands, with the second from below consisting of saw stones placed diagonally against one another. Snake heads protruded from this band at the corners, which are only partially preserved.

A roof ridge rises above the facade and rests on a band of meandering steps. Above that there is a wall area with three masks that are only directed towards the front and a simple top end. On the back, the roof ridge is decorated with diagonally placed stones. The function of the building is unclear, and the frequent appearance of the Chaak masks does not necessarily give any indication.

Associated Buildings

To the east and south of the Monjas annex are two small and relatively closed courtyards, which are among the last construction activities in this area. A change or expansion of the use of the complex could be connected with this. The south courtyard has only two narrow entrances from the outside: the one in the northeast runs along the corner of the annex, while the entrance from the west was made narrower by two pieces of wall. The western building is peculiar: when construction began on this building, which is based on the later structure of the Monjas , four entrances were planned, as can be seen from the bottom stones of the door jamb. However, only two doors were continued, while the soffits of the remaining two consist of raw masonry. That the doors were not completed can also be seen from the lack of lintels.

The east courtyard is a little more open. To the north is a small columned hall, followed by an angled network of rooms, whose narrow entrance in the corner is viewed as a measure to control and limit access. The eastern building has similar characteristics, even if the portico access initially appears open. These buildings are obviously a “private” area that should not be accessible to the general public.

Templo de los Paneles Esculpidos

The temple of sculpted wall surfaces, which also appears under other names with similar content (technical name 3C16) is located a little south of the platform of Caracol and thus northeast of Las Monjas. Originally there was only a platform measuring 17 × 12 meters, on the upper surface of which there was a temple with two parallel rooms. The first room forms a portico with only two columns, the one behind it can be reached through a central entrance.

A columned hall covering the entire width of the platform was later placed in front of the building. For this purpose, the original staircase was demolished and replaced by a staircase placed in front of the portico, which led up to the roof level of the portico, from where the uppermost part of the original staircase was reached. Under this later staircase there is a passage covered with a small vault in front of the actual portico. Even later, the side walls of the stairs were reinforced with an additional wall. The name of the building is given by two slightly sunken fields on the walls of the narrow sides of the portico. They show scenes with numerous people in bas-relief with a very rough execution. The bas-reliefs were originally covered with finely modeled stucco and brightly painted.

Akab Dzib

The Akab Dzib located about 150 meters east of Las Monjas hidden in the forest, close to a Yucatán as Rejoyada designated Einbruchsdoline that does not reach the ground water level. It is a complex building that owes its name, which means "dark writing", to a hieroglyphic inscription on the lower and front of the door beam at the south end.

The building consists of a stylistically early building with two west-facing rooms of unequal size, to which three entrances lead. These two rooms also form the oldest part of the building in terms of architectural stratigraphy. On both sides, to the north and south of this small building, two mirror-image blocks of eight rooms each with access from three sides were added. Their connection to the older building can be clearly seen from the different heights of the decorative strips on the facade (picture). The depth of the two blocks made it necessary and made it possible for another room of roughly the same size to be built behind most of the outer rooms, which, as usual, was one step higher. With this arrangement, models of the early Puuc style are taken up and modified. The building's facades are simple, as are the tripartite friezes. Behind (to the east) of the older component lies a massive core made of bulk masonry, on which a second floor was presumably supposed to be built, but this did not happen. Access to this floor would then have been via a "flying staircase" over the facade of the older component.

In the hieroglyphic inscription, Yahawal Cho 'K'ak', a member of the Kokom family, says that he owned this building. The construction of an apparently planned second floor on the core of bulk masonry did not come about.

Grupo de la Fecha

In the south at a distance of around 1.2 kilometers from the Castillo, near the sacbe 7, is the Grupo de la Fecha ("Group of the Date") or Grupo de la Serie Inicial, a wall surrounded by a large and a small one Archway to enter complex of large buildings.

The central and eponymous building is the relatively small temple, which was built in at least four different phases. The lintel bears an inscription with the only date of Chichén Itzá in the Long Count, which corresponds to July 30, 878. It was taken from an older building and originally had a different function; therefore he does not date the current building.