jade

| This article was entered on the quality assurance page of the WikiProject Minerals due to formal deficiencies in design or form and / or deficiencies in content . This is done in order to bring the quality of the articles on the subject of mineralogy to an acceptable level. It can also happen that articles are deleted that cannot be significantly improved (see also Wikipedia: What Wikipedia is not ). Be brave and help to remedy the shortcomings in this article.

|

Jade ( der or die ; from Chinese玉Yù ) is the name of various minerals, especially nephrite and jadeite , which must have certain optical properties in order to be considered the gemstone jade.

In China , jade has been used and valued for at least 8,000 years; Over time, a real jade culture even developed. Jade was also processed thousands of years ago in Europe , the Pacific , the Eastern Mediterranean and especially in Central America .

In the course of the colonial power politics of the major European powers towards the end of the 19th century, jade found its way increasingly into the jewelry culture of the West, after the Spaniards "rediscovered" it for Europe during the colonization of Central America. In the 1920s, jade even became a coveted fashion accessory . In the hippie culture of the 1960s and 1970s, jade was refined as a magical attribute and esoteric "philosopher's stone".

etymology

The term jade goes back to the Spanish piedra de ijada (roughly "loin stone" or "kidney stone"). In the co-mineral nephrite (from Greek νεφρός nephros "kidney") this meaning is also preserved linguistically. The term was adopted in French as l'éjade and incorrectly transformed to le jade around the 17th century .

The Spaniards first got to know jade in Central America , where it was processed by the indigenous people into healing stones and amulets against kidney disease. The term was then expanded in Europe to include jade of Chinese or Asian origin. Chinese is called Jade Yu (pronounced “Ü”).

The European definition of the term “jade” differs from the Chinese one, however, in that the noble serpentine has been revered and valued in China as the stone of the gods for thousands of years , and that the Chinese use this mineral called “Yu” in China as the original and genuine jade since the foreign term "jade" was known in China. In contrast, the term “jade” was defined in international commissions to the effect that noble serpentine was excluded from the group of minerals that may be called “jade” in the western world. In the western world, jade is a group of minerals that differs from the Chinese definition. In China, however, the jadeite and nephrite, which are known as jade in the western world, are also referred to as a type of jade, with the word "Fei-Tsui". On the photos shown within the article, therefore, you can probably see both nephrite, jadeite and noble serpentine.

Mineralogical definition and other varieties

The term "jade" is not a mineral name recognized by the International Mineralogical Association (IMA) and is mainly used for " nephrite " ( mixed crystals of the tremolite - actinolite series ) and the mineral jadeite , which belongs to the Na-Pyroxene group , but often also for far used cheaper, more or less similar looking minerals. In order to bear the name "Jade", the components must as microscopic aggregates are present, that is in microcrystalline form as the smallest, toothed, only with the microscope recognizable grains or matted fibers. Unlike the more often transparent to opaque nephrite, jadeite only very rarely forms real large crystals , is chemically white (this is also its line color ) and gets its color (mostly green, brown, reddish, yellow to purple) through other chemical compounds, with whom he almost always appears together. The green comes from small admixtures of chromium , chlorine and other ions . But white jade is also highly valued, especially in Chinese and Indian art.

The most sought-after and most expensive jade variety is the so-called "Imperial Jade" or "Kaiser Jade", a jadeite from Myanmar that is colored emerald green and has transparent edges due to the addition of chrome .

Other well-known varieties of jade or jade-like rocks are the greenish-black spotted, iron-rich and chromium-containing "chloromelanite" (mixture of jadeite, diopside and aegirine ); the light to dark green spotted "Jadealbit" (also albite jadeite or Maw Sit Sit , mixture of albite and jadeite from Myanmar) and the "magnetite jade" (trade name for gold-plated jade).

Education and Locations

Jadeite and nephrite are formed in the earth's crust due to pressure and / or heat through metamorphic transformation in the course of volcanic processes in subduction zones such as the Pacific Ring of Fire ( New Zealand , Guatemala , California , Japan , etc.). They also arise in tectonically highly active regions such as north of the Himalayas and the highlands of Tibet . Here the geological structure is strongly compressed by folding processes and by the pressure with which the non- subducting Indian continental plate presses against the Eurasian plate. This situation is particularly the case for the regions of Mongolia to the north and east of the highlands of Tibet, western India (Burma) and Xinjiang . The richest sites are therefore located in such regions. In the valleys of mountain rivers, the jade is transported down into the valley as rubble from its actual areas of origin, the orogenetic rift and folding zones.

For a long time Jade is also mined mined and collected not only on the surface. Jade occurs preferentially in crystalline slates . Main sites were and are the Santa Rita Mountains between Santa Maria and Santa Barbara as well as in other parts of California, which generally - probably due to its geological situation at the San Andreas Fissure - has rich jade deposits and where crystals can also be found. A classic site is Tharrawaw in western Myanmar (Burma), from where jade (jadeite) has been imported since the late 18th century. There are other larger sites in Canada , Silesia , Itoigawa , Japan , in Guatemala (Valley of the Río Motagua ), Mexico (especially on the southern Gulf coast of the Yucatan ), on New Guinea and the South Island of New Zealand , in Italy and on Sulawesi (Celebes).

Most of the jades processed in China came from Xinjiang before the 18th century. At that time, jade was mainly recovered as superficial rubble from the Hotan and Yarkant rivers , both located on the southern arm of the Silk Road. In their tributaries Karakash and those of the Yurungkash, blocks weighing up to 30 t occurred. White and green jade was found in Khotan, mainly as pebbles and rubble in the waters flowing north from the Kuen-Lun Mountains into the Takla-Makan Desert. The river jade was found mainly in the area of the Yarkant, the white jade was found especially in the Yurungkash, the black in the Karakash river. From there, from the Kingdom of Khotan on the southern branch of the Silk Road, most of the jade came to China as part of tribute payments. However, recent research suggests that nephrite deposits once existed in Manchuria , in Lantian and Shanxi and on the lower reaches of the Yangtze River. However, it is debatable whether jade was already brought over these enormous distances (approx. 2000 to 3000 km through deserts and high mountains) in the Neolithic . The Silk Road (see map below) in any case only reached its eastern dimension during the reign of the Han dynasty shortly before the turn of the century, when it grew in size under the Han emperor Han Wudi (141-87 BC) in defense of the constant border threats of the Han Empire almost doubled and the victory over the Xiongnu equestrian nomads finally brought control of Central Asia. Linked to this was control of the jade deposits there.

Varieties of lesser value consisting of other minerals can be found in South Africa (Transvaal jade) and Greece , among others . Yunnan, which is often mentioned in the literature , is not a site of jadeite, because it was only the jade imported from Burma since the late 18th century, on which the Chinese had a monopoly for a long time and which was traded there on a large scale as an export good , whereby there may have been factory-like manufacturing processes.

The annual production in Burma in 1993 was 300 tons of material and today (2009) has decreased to approx. 150 tons due to poor mining conditions and the political market situation there (military dictatorship).

History and cultural history

Jade is regarded both as a gemstone and because of its cultural-historical importance up to the belief in its healing properties, as one of the most remarkable minerals of all. It is not even a mineral in the strict sense. Jade is too valuable and difficult to work with to be used as a raw material for tools. Even making a simple amulet can take days. Therefore only ceremonial weapons and tools were made from them, such as the jade axes found in Central Europe , France , Switzerland and England . Otherwise, jade was and is often processed into jewelry, used in handicrafts and, due to the magical qualities that are sometimes attributed to the material - in the broadest sense - used for corresponding cultic or magical rituals.

In the following, therefore, the cultural zones and periods are first presented in more detail, in which jade was either of independent artistic importance and the processing of jade developed its own styles or where a spiritual-religious world of ideas arose that had jade as its subject. Jade as a coveted and valuable commodity was sporadically present in other cultural zones than those shown below, but mostly did not acquire any special or only secondary importance, such as in Egypt, where it was possibly used for amulets and rings. It was also a rare luxury item throughout the ancient Mediterranean. Jade was used for various purposes, mostly decorative and status, because it was particularly rare, valuable and difficult to work with. However, there is no verifiable world of ideas of a religious-philosophical kind associated with it in these cultural areas, at most possibly in Rome from the first century AD as a fashionable, eclectic takeover from other cultures.

In this cultural-historical context, however, the definition of jade must be understood further than the mineralogically modern one described above and includes not only nephrite, but also jadeite and the serpentine, which is also referred to, from which the sporadic seals of Mesopotamia and precious vessels of Crete were made, but also various objects such as Olmec , Maya and Māori art - quite apart from the fact that what the Egyptians and other Mediterranean cultures called "green stone" was certainly not jade.

Meaning in history

Jade has achieved great importance as jewelry in several ancient cultures, but especially in the Chinese, where even one of the great mythical heroes of culture bears the title of jade emperor and jade plays an important role in poetry and philosophy. Jade was also extremely valued in Mesoamerica , primarily because of its hardness, toughness and rarity. The emerald green jade, which was more valuable than gold, was considered particularly valuable.

Although jade occurs in practically all parts of the world, the peoples of the Pacific and especially the Chinese, who wove a real ethic and mythology around it, as well as the Olmec and Maya of Central America and the Māori of New Zealand, who used jade not only for decorative purposes. Why this is so and why jade is largely absent in other cultures is still controversial in research today. In fact, if one consults a map of the world, one could speak of a veritable “jade zone” that stretches from early ancient Europe with its jade axes and the shamanic North Asia to this day, via Central Asia to China, Korea and Japan, touching New Zealand and ending in Mesoamerica . Whether these geographic contexts are also based on ethnic and cultural factors (e.g. in the case of the settlement of America and Oceania), especially if one also takes into account the regional temporal gradations, is open and highly speculative.

Paleo- and Neolithic, early history

Old Stone Age

The oldest jade objects are dated to the end of the Paleolithic . For example, cut nephrite stones were found near Buret in the Siberian Irkutsk region. They can be assigned to the late Upper Paleolithic , as female statuettes of the Venus type were found here, which are at most 29,000 years old and typologically belong to the Gravettian .

Neolithic and recent indigenous cultures

For the Neolithic , the use of jade can be proven archaeologically in northern, eastern and western Europe, in large parts of Asia and in Central America, and there was obviously already then a far-reaching trade in this coveted and relatively easy to transport, thus also as a barter suitable material, which one gradually learned to refine more and more by grinding and carving. In addition to jade axes, jewelry and amulets made of jade, vessels, small sculptures and reliefs are often found . Most of these objects come from graves and were partly made especially for burials or were ceremonial and status symbols.

Asia

China was probably the center here because of its rich and easily accessible deposits, and jade objects up to 8,000 years old have been discovered here in many places. In total there are about 10,000 jade finds from the Chinese Neolithic in over 100 sites. Jade must have been so important in Chinese culture early on that Chinese historians 2000 years ago, in addition to the Stone, Bronze and Iron Ages (they knew these terms, which were first used in Europe around 1830 by the Danish antiquarian Christian Jürgensen Thomsen and others introduced a jade time (yuqi shidai) , which was the starting point for the later Chinese jade culture.

In addition to its easier availability, two reasons are assumed for this prehistorically high appreciation of jade:

- The formation of stratified societies in the transition from primitive tribal society to statehood brought with it the need for status symbols for the leaders.

- The main duties of these leaders were sacrifice and warfare. Jade was seen as magical matter (shenwu) .

Around the time of the mythical "yellow emperor" Huangdi (a title that means something like "exalted ruler", roughly comparable to the Roman "Augustus", and which the Qui rulers already adopted as a title) people began to do so Collection of legends of the Yuyueshu of the Eastern Han period reports that weapons that were previously made of stone were also made from jade, which was believed to give them magical power. Under the Jade Emperor Yu Di , the weapons were allegedly made from bronze again.

Neolithic beliefs and ritual practices decisively promoted the development of ritual jade , especially in the Chinese coastal regions. The earliest forms of this culture emerged in the crescent-shaped jade belt there (which strongly suggests that there must have been corresponding sites there, presumably of rubble jade on the Yangtze, for example ). Early centers of a jade culture were above all the north Chinese Hongshan culture (approx. 4000-3000 BC) and the southeast Chinese Liangzhu culture (approx. 3300 to 2200 BC). The Liangzhu jade culture was the last Neolithic jade culture in the Yangtze Delta. The jade art of this time shaped large ritual vessels and ritual objects of unclear meaning such as Cong tubes and Bi disks , which are believed to symbolize earth and sky, as well as ritual Yue, probably intended for human and / or animal sacrifices. Axes and pendants and amulets in the form of birds, turtles or fish. The Liangzhu jade was milky white. It is uncertain whether this preference has a ritual, symbolic background or was simply due to the better local availability of white jade. Jade was primarily used to worship the gods. For the culturally possibly related phenomena of Siberian shamanism, in particular the toli mirror of the Buryats, and the parallels to the burial ground of Jinggangshan, see the section on Shamanism of Siberia and the Ainu .

Outside of China, jade objects can also be found in Korea and Japan (Magatamas), in the Indus culture , where they were apparently imported via the Himalayas from Central Asia and the jade sites there, because there were and are no jade sites in India itself. In the Middle East , the Caucasus , India and Pakistan , club heads made of jade can be found as status symbols, as well as in the Philippines (a finely crafted ax), where they probably came on early trade routes, because southern China and Vietnam were also flat in winter with the help of the northeast monsoon Easy access to boats along the coast.

Europe and the Mediterranean region

During the fifth and fourth millennium BC, axes were made from alpine jade, which were then mainly found in Switzerland. Representative of the late Neolithic of the third millennium BC in Europe are the jade axes, which were particularly widespread in the Rhine area between Hesse and the Netherlands and were also found in Brittany and on the British Isles (Somerset). In the large deposit found in Mainz-Gonsenheim , they are attributed to the so-called bell beaker culture (2500–2200 BC). There they are up to 35 cm long, flat and carefully sanded. Because of their fragility, these can only have been ceremonial weapons for high dignitaries.

In the rest of Central Europe as well as in Southern and Eastern Europe, however, jade objects are missing (with the exception of Crete, see below ).

Egypt Ceremonial clubs were also found

in pre- and early dynastic Egypt. However, jade was only used relatively rarely in art and religion there, but it may be known as a gemstone and ascribed magical qualities to it, like other gemstones . For example, one of Tutankhamun's 15 rings is made of nephrite (but the material is uncertain) and contains a not very artistic bas-relief representation of the king and the god of fertility, Min , who is always depicted with an erect penis. The fact that the Egyptians developed their own jade technology is rather unlikely due to the sparse finds, and as far as is known, Egypt did not and does not have any jade deposits (which would be geologically unlikely). Presumably they imported jade objects that the Phoenicians traded in, which they knew from Crete and Canaan , received them from other peoples as part of tribute payments, or brought them with them from their conquests of Canaan and Nubia down to the legendary Punt .

Mesoamerica, North and South America

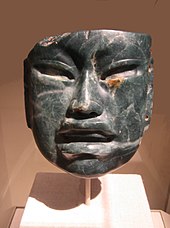

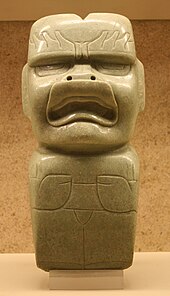

The late Neolithic culture of the Olmecs, which is considered to be the mother culture of Mesoamerica, used jade for ceremonial objects and sculptures like the Mayans later, except for medicinal and magical purposes.

However, since the pre-Columbian Mesoamerican advanced cultures learned metalworking very late (around AD 900, when the Toltecs presumably took them over from South America for gold and copper, but never learned how to make bronze) and then the objects preferably made from soft copper Only used for ceremonial purposes or for jewelry, the classic division into stone and metal ages is not used here (one subdivides into archaic, formative, classical and post-classical). For the Mesoamerican jade art as such, see the corresponding section .

In South America, especially in the Andean cultures, where gold and turquoise were particularly popular, in the Caribbean and the Amazon region, however, there is hardly any jade art, and what little comes from imports from Central America, especially since both the Caribbean and northern South America are at times in the cultural area of the Mesoamerican cultures and also shared certain mythological concepts with them. This is especially true for the occasional use of jade for mostly ritual purposes in Colombia and Ecuador , for example in the Tairona culture .

The situation is similar in North America. At best, traces can be found in the area of the Pueblo Indians , which is adjacent to the Mesoamerican cultural area . But here too, turquoise was particularly preferred as it was apparently readily available and much easier to work with.

China - the jade culture

Jade was most important in Chinese culture, where it was not only important artistically as a material, but also ideally as a symbol in religion, philosophy, literature and even in statecraft. Even today, people in China believe that jade has healing powers. It is therefore wrong and practically impossible to exclude the aspect of philosophy and religion from a representation of the art of jade, especially in China.

For purely art-historical details, see the article on Chinese art .

Historical development

For the chronological list of the dynasties, see the China chronological table and the detailed history of China .

With the beginning of the Xia dynasty founded by the legendary Jade Emperor Yu Di around 2200 BC. The manufacture of jade devices reached a new technical level through the use of bronze devices to process them. In the subsequent Shang dynasty from 1700 BC Ancestor worship began to expand, especially among the ruling classes, and the cult of the supreme god Huangdi gained in importance. The use of jade objects, especially sacrificial tiles and carvings, for the sacrificial rituals expanded considerably, because jade was considered indestructible and it was believed that it preserved life force. This now applies even to the graves of the common people. Obviously, certain rituals related to jade were already observed.

This ritual system was already fully developed in the Shang Dynasty (16th – 11th centuries BC) and the Western Zhou period (11th century - 771 BC) . The largest part of this time no longer make up the jewelry jades, but the ritual jades. However, these went back massively in the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (720-256 BC). However, jade carving was already highly developed in the Shang period within the scope of the technical possibilities at that time. In addition to ritual devices such as heaven and earth symbols (jade disks pierced in the middle: bi ) and sceptres for the various degrees of nobility, there were also ornamental jade, i.e. figurative sculptures (tiger, bear, rabbit, deer, etc.); even musical instruments (sound stone game). Articles of daily use such as belt clasps, dress decorations etc. were now also made from jade. The Bi disks in particular also seemed to have served astronomical purposes, especially to determine the north, as the circumpolar stars formed a perfect circle when looking through the edge of the disk and could thus replace the North Star, which was not clearly visible in China at that time, for determining direction. This could well have resulted in an increasingly magical geomantic use of such disks, if, for example, as is still common in China's Feng Shui today, the optimal locations for buildings, graves, etc. were determined. The step to the magic and holiness of jade and as a heavenly symbol was then no longer too great and, as in many such cases, soon made us forget the secular cause. Other such ritual jade symbols were the disk kuei for the north, chang for the south, the tiger for the west and the huang for the east. During burials, the nine body openings were closed with jade plates. There were ritual jades for all sorts of other purposes, the six most important rui jades signaling the social rank of the bearers: bi, cong, gui, zhang, huang and hu , to which there were also secondary axes like the yue axes mentioned above . Overall, the frequency of the dragon symbolism in the objects is noticeable through almost all periods (images on the left) .

The emergence of iron processing during the spring and autumn annals and the Warring States 720 to 221 BC. BC reformed the production of jade again. A new era of jade production began. Some of the most precious finds of all date from this time of the Golden Jade Period . Jade was now massively used by the senior class and worn all over the body. However, even now the largest known jade figure was no higher than 18 cm.

However, as early as the first millennium BC, the material jade was in competition with other materials and processing techniques. Another negative effect was that jade, due to its ideal and partly metaphysical meaning, was not particularly suitable for certain purely secular purposes and also seemed to be of little use for larger art objects such as large sculptures or in architecture. Preferred materials, because they could be used more flexibly and were easier to produce or process, were now porcelain and ceramics, lacquer, silk and bronze and precious metals, which, however, like ceramics, silk and lacquer, have also long been in use, as well as the traditional ivory as a derivative of archaic bone carvings the oracle bone , which, however, only gained greater importance from around the 18th century. In the meantime, techniques emerged or were greatly refined: woodcuts, painting, ink drawings, calligraphy and letterpress printing, which in China was never used with movable type. After the second high point of Confucian jade art during the Song Dynasty (960–1279), jade played during the Ming, which was mainly famous for its lacquer, painting, especially porcelain and ceramics, but also restoratively oriented towards the Tang Dynasty (618–907) -Dynasty 1368-1644 only a rather subordinate role. It was mainly used as an ornament on clothing in the form of pearls, buckles, as draping of precious silk garments and for the production of fine bowls, with the white jade being particularly valued as the most precious variant.

In fact, the following as Manchu known Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) it came finally to that fateful spiritual torpor and isolation, the artistic found expression in an ever more eclectic, formalism and overloaded Mannerism with a lack of originality, as is generally common as a late cultural phenomenon. Ultimately, this spiritual tendency led to China becoming a victim of the American and European, and later also of the Japanese, colonial powers economically and politically in the 18th and especially in the 19th century ( First Opium War , Second Opium War , Boxer Uprising , Hong Kong , etc.). Jade, like porcelain, silk and lacquer work as well as painting, was and had been produced in large quantities for export as chinoiserie, which is valued in Europe (the majority of the jade objects available today in Europe and the USA dates from the 19th century) almost completely lost their ideal character. The very individually processed jade was also completely unsuitable for such large series, and the jade objects of that time are therefore rather cheap artisan products or made from jade substitutes, a characteristic that they mainly use today with many "art products" made for tourists and esotericists Third world countries.

In the modern age , jade officially hardly plays a role in Chinese art (except for export and often as a substitute for jade), especially since in the People's Republic of China, at least until its economic-capitalist reorientation in the 1980s and 1990s, it was considered an elitist and thus "bourgeois" art “Material was viewed rather negligently and was considered reactionary during the Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1970 and 1973 to 1976 and, like other art labeled in this way, was often destroyed by the Red Guards . Only after its end (the arrest of the Gang of Four ) did jade carving flourish again with increased tourism and the privatization of life that developed in the course of Deng Xiaoping's capitalist economic reforms .

Nevertheless, the people who, despite communism, have always maintained Confucian, Buddhist and Taoist (and regionally also Muslim and Lamaist) customs and attitudes, still enjoy great esteem among the people, and the Chinese still today rate the quality of jade by its color. The green color of a jade is a symbol of good luck. The (very rare) discoloration of jade jewelry is considered a sign of bad luck. The (also rare) breaking of a jade object brings bad luck. A jade gift is also a proof of love.

Jade in philosophy, religion, language and literature

It was in the period shortly before and during the emergence of Confucianism that a comprehensive and highly complex system of rites developed around the jade. The symbolic connection of jade with the male principle yang of the yin-yang system, which later became so important for the connection between ruler and jade (the emperor's seal was made of jade, not gold), arose against the background of religious beliefs and philosophical debates. Already in between 1050 and 256 BC I Ching , which originated in the 4th century and contains Taoist and Confucian thoughts, says: "The Qian diagram stands for heaven, for the round, for the ruler, for the father, for gold, for jade ..."

Simultaneously, philosophers like Mozi and the legalists like Han Feizi began to condemn this fashion, while Confucius again defended Jade. The rite system Li, which consisted of five basic rites (joyful, mourning, reception, military and holiday rites) later solidified into a code of rites, from now on formed an essential part of the social structure in ancient China. In the following centuries it was mainly cultivated by Confucianism , especially as it was after the unification of the empire around 221 BC. By Qin Shihuangdi , the first historical emperor of China (he became world famous for the discovery of his terracotta army ) and founder of the Qin dynasty , under the emperor Han Wudi (ruled 140-87 BC, Western Han dynasty ) rose to state doctrine.

This gave the Confucian jade ethics central importance, which was now closely related to the ritual jade system. Jade was given philosophical and ethical-moral terms, linked to the yin-yang doctrine and finally linked to the now rigid ranks of the nobility, for which it had previously had a purely ritual meaning, and thus also politicized as a symbol of power. This ritual jade system determined, for example, which layers of higher society were allowed to use and wear which ceremonial jads and thus put them at the service of a society structure based on moral and ethical norms, based on the patriarchal system and strictly hierarchical, since this wearing of ritual jads is no longer possible as was previously the case, for example in contact with higher or lower placed up to the emperor, but froze into a formalism signaling social barriers with a philosophical superstructure. The system gradually became extremely complex and had such an impact on the design of jewelry jades, for example, that its interpretation is impossible without precise knowledge of the social and philosophical-ethical background. The result was a real ethics of the jewelry jades , the core principle of which was: “The noble one compares his virtue with jade.” This development had already started early during the Zhou period and was laid down in the Zhouli (around 300 BC). According to another Confucian classic, the Book of Rites , the real value of jade is not in its external beauty, but in its virtue. It says in it:

“Tse-Gung said to Confucius, 'Allow me to ask why jade is so valued and alabaster is not. Is it because jade is so rare while alabaster is more common? ' Confucius replied: 'If the wise men of old cared little about alabaster but valued jade, it has nothing to do with the fact that alabaster or jade is common or rare, but is because the wise men used jade to practice their virtue compared: It stands for humanity because it feels mild and soft. It stands for knowledge, as its grain is fine, dense and resistant. It stands for righteousness because while it hangs on the body, it does not hurt it. It stands for appropriate behavior, as it - hanging from the belt - seems to bend down to the floor. It stands for music because it makes clear and long-lasting sublime sounds that end abruptly. It stands for loyalty, as its shine neither conceals imperfections, nor is it itself veiled by imperfection. It stands for trust because its good inner qualities are visible from the outside. It represents the sky in that it resembles a white rainbow. It stands for the earth as it embodies the forces inherent in mountains and rivers. It stands for virtue, as do the ritual jade objects used in audiences. It stands for the path of virtue because there is no one on earth who does not appreciate it. '"

Even with pure jewelry pendants, this originally purely philosophical thought finally came to the fore. During the Han dynasty, this even affected the funerary robes, the so-called jade armor (玉 甲yù jiǎ ), which were extremely expensive and reserved only for the highest dignitaries. In one of the rock tombs in Mancheng, for example, two funeral robes made of jade were found, each made of more than 2000 pieces of jade fastened with gold wire. The purpose was to magically protect the corpse from decay. A slightly cheaper burial method was the Jademumifizierung to sew onto which goes back to the already testified during the Spring and Autumn Annals custom shrouds with Jadeplättchen and seal the nine orifices with them. Overall, the Western Han period of jade culture is a high point that has never been surpassed at any time in Chinese history, because the level of craftsmanship and the breadth of artistic representation now overshadowed everything previously. But even the collapse of the Han Empire and the decline of Confucianism between the 3rd and 6th centuries did not mean the end of the Chinese jade culture, rather it was further developed by a Taoist undercurrent with its funeral jades and its magical devices. After the reunification of the Chinese Empire between 581 and 907, Confucianism, which had now also adopted Taoist and Buddhist ideas, gained new power and renewed the Chinese jade culture, even leading it to its last climax, which is marked by the "appointment" from the cultural hero Yu Di (玉帝yù dì ) to the legendary jade emperor at the time of the Song dynasty by the emperor Zhenzong in 1015.

Most of the literature on jade deals with its philosophical and religious-ritual character, as shown above. For example, an inscription on a bronze vessel from the Zhou period says:

“There is no ancestral spirit to whom we have not made sacrifices,

nor have we reluctantly slaughtered the sacrificial animals.

We have all offered our jaden ritual vessels.

Why are we not heard by the ancestral spirits? "

Already early and in the Neolithic it was believed that jade made it possible for people to come into contact with the gods and used it in the still shamanic spiritual-religious context as a medium between the earthly and the supernatural sphere, because it was considered to be " Essence of the Power of the Mountains ”from which it was carried by the rivers. Beyond this magical aspect, the idea of purity, beauty and sublimity was connected, and from observations on natural stone one inferred two main characteristics of jade: beauty and virtue, which up to the outer aspect of unobtrusive harmony, the most important principle of East Asian thought today, with the internal, the toughness and resistance to coercion and violence combine. Jade was also later, as mentioned, the embodiment of the lighter, male Yang principle within the Yin-Yang duality, and it was the symbol for life force. Because of such symbolism, jade also played an important role in poetry, especially in poetry, and in literature jade not only meant the noble material, the gemstone itself with its coolness, hardness, and smoothness, but at the same time refinement and beauty, in particular in women. This highly metaphorical principle is already contained in the oldest comprehensive dictionary of the Chinese language Shuowen jiezi by the author Xu Shen from the 2nd century AD, where the character for jade is paraphrased as follows:

"Jade is beauty in stone [shi zi mei] with five virtues: its warm luster stands for humanity, its flawless purity for moral integrity, its pleasant sound for wisdom, its hardness for justice and its constancy for endurance and bravery."

The Chinese written language has accordingly developed over five hundred characters under the term jade, and there are innumerable combinations with the character for jade (yu). The jade imagery is extraordinarily diverse. One speaks, for example, of “jade heart” meaning “pure heart”, of “jade face” and “jade face” for a beautiful woman. Jade is also common in proverbs. “Making jade devices with the stones of another mountain” means that you work on your own perfecting with outside forces. The noble disposition of a person is described as "with precious jade in the heart and in the hand". “Burning jade and stone to ashes” means senseless destruction. “Better a broken jade than an intact brick” corresponds to the German “Better to die honestly than shamefully spoiled”. It is also significant that the poetry of the Confucian period was mainly borne by the state officials and was massively influenced by their use of language. At times, “dense” was even part of the entrance exam for the civil service.

As epithet refined jade in Chinese terms. The Jade Pagoda west of Beijing - it stands on the hill of the jade spring - is of course not made of jade, but venerable like jade, the same applies to the Jade Buddha Temple in Shanghai, founded in 1882 , which, however, contains two jade Buddhas from Burma: a seated (1.95 m high, 3 t) and a smaller reclining one depicting the death of the Buddha. There is also a jade pagoda in Ho Chi Minh City (formerly Saigon) (it dates from the beginning of the 20th century and is Cantonese). If the sound stones of the ancient sound stone game are made of jade, the music produced with them takes on the noble character of jade, as Confucius testified. The idea of the precious can even be found in a book by the Chinese mathematician Zhu Shijie , the Siyuan yujian, ie the " Jade Mirror of the Four Unknowns", and one of the highest orders in the People's Republic of China is the Jade Order. The examples could be multiplied at will, for example around the Jade Dragon Snow Mountain near Lijiang; and even today the epithet is linguistically highly effective when, for example, Chinese youth groups call themselves the “jade dragons”, as many examples on the Internet show. In general, the connection between “jade” and “dragon”, which in Chinese mythology is considered a lucky male symbol, which was and is often the subject of portrayal and contemplation in art, philosophy and poetry, is perceived as particularly noble.

Mesoamerica

Timeframe

For the geographical localization of the individual Mesoamerican cultural regions see Commons. See also the detailed table in Chronology of Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica .

There are roughly 5 cultural areas in Central America:

- The central highlands with the valley of Mexico

- The Gulf coast with the Veracruz region as the Olmec heartland

- The Oaxaca Valley and the Tetihuacán Valley

- North and West Mexico with the Pacific coast

- Campeche / Yucatan.

It should be noted here the relatively complex sequence of individual cultures, which were often only decisive as urban cultures for a smaller area of Mexico and Guatemala and sometimes existed parallel to one another, and occasionally war:

- Approx. around 2000 to 1650 BC The earliest forerunners of the Olmecs can be found on the Gulf coast in San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan , the culture there ended around 1150 BC. Chr.

- Approx. around 1600 and 1500 BC The Barra culture and the Ocós culture can be found on the Pacific coast as further forerunners of the Olmecs.

- The actual Olmec culture lasted from about 1200 to 200 BC. With the climax of the La Venta culture around 400 BC. The Olmec probably invented and developed writing and calendars.

- They were made around 200 BC. Chr. Replaced by the Izapa culture, which passed into the Maya culture, which collapsed around 800 AD. The cities of Tikal , Palenque , Chichen Itza and Copán were important centers of the Maya .

- Smaller Epi-Olmec cultural groups such as the Veracruz culture with Tres Zapotes and Cerro de las Mesas as centers and the as yet hardly investigated Remojadas culture formed in the following centuries all the way down to Guatemala.

- At the same time, there was the culture of Teotihuacán from the turn of the ages to around the middle of the 7th century AD

- and the Zapotec culture of Monte Alban between 400 and 800 AD.

- as well as the culture of Huaxtecs (Tajin I) and Totonac (Tajin II and III) of El Tajin between 500 and 900 n. Chr. There was also the Chichimecs and Tarascan 700-1200, which were less cultural than linguistic and ethnic groups and are.

- The Toltec culture lasted from 900 to 1200 AD.

- The culture of Oaxaca flourished in the 13th century,

- that of the Mixtecs in the 14th to mid-15th centuries.

- In turn, it overlaps with the Aztec culture , which lasted from the mid-14th to the first few years of the 16th century and became famous for its excessive sacrificial rituals with massive human sacrifices, which also existed in other Mesoamerican cultures.

use

Olmecs

In the pre-Columbian civilizations of Central America, it was mainly the Olmecs and Mayans who used jade. In Uaxactún, for example, a 25 cm high and 5 kg heavy jade statuette with typical Olmec facial features was found. A large deposit with 780 jade figures comes from Cerro de las Mesas. Already between 400 and 300 BC When Olmec destroyed La Venta in the vicinity of which several large deposits of jade had been discovered - they were the main source of wealth there even after the Conquista - serpentine was apparently also used for architectural purposes. Within a huge ritual area with graves, temples and a pyramid, there were also three mosaic floors, later ritually covered with earth, made up of over 485 serpentine blocks each, which represent stylized Werjaguarmmasks. The jaguar man (Werjaguar), whose figure combines features of a human and a jaguar, was a powerful myth and a symbol of the sun and gods in many pre-Columbian cultures. The famous Las Limas Monument 1 contains this idea in a nephrite sculpture, which depicts a youngster who is holding a slender Werjaguar baby in his arms. The statuette was found in the Mexican state of Veracruz, the Olmec heartland. The statuette is so famous primarily because it shows the Olmec notions of the supernatural so clearly, and it is therefore occasionally called the "Rosetta Stone of the Olmec religion". She is also known as the "Las Limas figure" and as the "Señor de las Limas" (see picture above left) . Numerous jade votive offerings such as jade axes were also found. Particularly in the case of the Olmecs, the stylistic similarity of the small figures, presumably representing devotional objects, with the often meter-high large stone sculptures is striking, although it is now assumed that the jade objects belong to a younger Olmec epoch.

Mayans

Excellent jade objects come from Teotihuacán , the Mayan and Zapotec times. Jade mosaic masks were found in Monte Albán II (a bat mask made of 25 stones), in Palenque and particularly often in Calakmul . The origin of the jade was then, as it was later, the large site in the Montagua Valley (now Guatemala) and the Gulf Coast. Serpentine and nephrite were also used. In the so-called "Holy Well" of Chichén Itzá , a large Mayan center in the Yucatan, thousands of objects were found, including numerous ornate jade objects that had been thrown into the well as offerings, an unparalleled archaeological treasure found in one of these on the Yucatan found the widespread underground cenote , as those huge karst cave systems are called, hundreds of which run through the whole underground there over many kilometers and whose exploration has only just begun, especially since they were apparently often used for ritual purposes or even underworld temples (wells and caves were considered worldwide in religions as access to the underworld). The death mask of the Maya king Pacal II ("the great"), discovered in 1952, became particularly famous around 700 AD in Palenque.

Intangible interpretation of jade

In contrast to China, for example, the languages and scripts of the Mesoamerican cultures are only known in part. But this means that little is known about the intangible content of their culture (the Popol Vuh is one of the few exceptions), because the ideograms have not yet been fully deciphered ( however, great progress has been made with the hieroglyphs of Maya writing ). This means that it is often only possible to draw indirect conclusions about the potential significance of jade among the peoples of Mesoamerica . These conclusions are based partly on the objects shown, partly on the locations, partly indirectly on the evaluation of the material in terms of preciousness, workability, etc. With some Olmec jade figures, however, one has the assumption that they could be related to the rain god, but whether that is has a direct connection to the material is questionable. The decisive factor here, as in other non-Chinese cultures, was its rarity and preciousness, which here could have been linked to the fertility symbolism of the color green. The light green jade is occasionally identified with the young corn god Centéotl as a representative of the young corn cob Xilonon, from which one differentiates Tlamatecuhtli "woman with the old skirt", i.e. the dried-up cob surrounded by wrinkled leaves. ( Maize was of fundamental economic and therefore cultural-symbolic importance in all pre-Columbian cultures.) The blue jade from Guatemala, on the other hand, seems to have been associated with water and its springs in the Olmecs and their rituals.

A possibly more complex, systematized and not only optically oriented symbolic content, as it exists in China, for example, is speculative, especially since one often does not know exactly who or what is actually represented in the figures or busts and for what purpose. After all, the goddess of the sea, lakes and rivers as well as fertility is called Chalchiuhtlicue ( Nahua ), "Die-mit-dem-Jaderock", or Matlalcueye, "Blaurock", and among the Mayans there were numerous often finely crafted sacrificial wells Jade relief tiles, so that at least a religious reference cannot be ruled out with the jade. At least it seems to be certain that there was also an intangible value of jade in the Mesoamerican cultures that lay beyond their material value. Possibly this was actually due to the color, which could have been perceived as a reflection of water and flora and was thus associated with life with the corresponding religious and spiritual consequences. In any case, the Mayans put pieces of jade in the mouths of the dead, which reflected their idea of living on in what they thought was a very comfortable afterlife, which corresponded to the respective status of the dead in this world and the type of death (there were four regions of the hereafter, one for each direction) .

But the Mayans probably also associated jade with sun and wind, because many Mayan jade sculptures have been found that could represent the wind god, but also breath and wind symbols as well as the wind directions. And a large jade sculpture of the Mayans found in Altun Ha , it weighs 4.42 kg, shows the head of the Mayan sun god. Still, the meaning of jade in Mesoamerican religions remains controversial.

A religious reference of jade would not be surprising among the peoples of Mesoamerica, because jade was after all, as we know, the most precious material of those Central American cultures, even before gold and the popular turquoise and onyx or quetzal feathers, and its preferred use in ceremonial or ritual objects such as parts of rulers' ornaments, death masks, cult axes, statuettes of gods or offerings is actually almost proving. However, since metal tools were missing and the copper, which was introduced late, was too soft, great difficulties arose during processing, and the representation was so limited, although one can certainly find works of art that are on a par with the Chinese, such as small Olmec busts and astonishingly finely crafted , mostly only a few centimeters tall figures, especially from the La Venta culture , which seems to have been an Olmec center of jade art at all. But you can also find finely honed ceremonial axes, similar to those found in the European Neolithic and the Māori. Most of the work was done by sanding, drilling and carving. Thin platelets were produced which were put together with turquoise on wood to form a mask. Pearls could also be made in this way. Probably by carving with the help of other pieces of jade or hard wood, small sculptures can also be made. Larger figures like the one mentioned above are likely to have been the exception.

From the final phase of the Aztec empire, the Nahuatl poetry, which was once transcribed into Latin letters by missionaries, is a moving swan song for the Aztec culture after the arrival of the Spaniards. The verses are attributed to the poet king Nezahualcóyotl ("Fasting Coyote") and also refer to jade:

Even jade is shattered,

even gold is destroyed,

even quetzal feathers are torn ...

One does not live forever on this earth:

we only linger for a moment.

Other cultural areas

Jade has only achieved such a central spiritual meaning in China and, provided with traditional ambiguities, in Mesoamerica, where it appears frequently in offerings and as an attribute of gods. However, artistically significant works of jade were also created in other cultural areas. This is especially true of Mughal India and Korea. In shamanism in North Asia and also in the Ainu, jade seems to have had a religious meaning, as it did in the early days of Japan and Korea, and in some cases still has it, also in New Zealand of the Māoris, where it also had a socially determined ceremonial value as a status symbol for the chiefs.

India and back India

One of the oldest examples of jade art in India is the Jain temple of Kolanpak or Kolanupaka, which is dedicated to the founder of the religion Mahavira , 80 km from Haiderabad (Andhra Pradesh). It is about 2000 years old and contains a carved jade sculpture more than 1.50 m high, depicting Mahavira, the largest free-standing jade sculpture in the world. The material jade, perhaps even the whole plastic, may have been introduced, because South India (the Deccan ), which was ruled by the Shatavahanas at that time, was at that time the center of a worldwide trade network that reached as far as Rome, Central Asia and China. And since Jainism, which was concentrated in South India, did not compete with Hinduism and was firmly anchored in the high ranks of society, it certainly had the means for such costly undertakings, as its numerous magnificent temples show. This jade statue was not an autochthonous Indian art, but imported and probably for that reason did not find any successors. (You can compare this with the Statue of Liberty designed and manufactured in France.)

In India, however, jade was not used again until the Mughal Empire between 1526 and 1858 to decorate valuable vessels and for sword and dagger handles and scabbards. Many such objects have survived, particularly from the 18th and 19th centuries. However, their quality cannot be classified with certainty in the larger art-historical context of a specific regional jade art.

The most important period of jade carving, however, was the 17th century. There are some unique pieces here, especially from the reign of the Mughal emperor Jahangir (1569–1627), such as his white jade wine bowl, and Shah Jahan (1592–1666), who built the Taj Mahal and in its time also the art of inlay with jade experienced a boom, which from then on formed the special characteristic of Indian jade art. The Mughals probably brought the art of jade carving from their Central Asian Timurid homeland of Turkestan and eastern Iran to India, where it was previously unknown.

Although there are large jade deposits in the Burmese rear of India, no actual jade art has survived for this region. This may be due to the fact that these sites were only known since the 18th century, but most of all because they were apparently used immediately by the Chinese, especially since very high quality jade came from there (e.g. "Emperor Jade") ). In addition, the principle applies here again that jade art could only emerge autochthonously where an undisturbed development of jade craft was possible to some extent, i.e. not in ethnically or religiously heterogeneous (Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, Christianity), of overlapping Indian-Chinese-Malay Power influences shaped rear India with its warlike convulsions that continue to this day, for example from the Khmer , Thai or the mountain peoples .

Japan and Korea

The most famous jade objects in both cultural areas include the jade ornaments called Magatama in Japan , which are shaped like a comma with a small perforation at the thicker end, which originally served to pull a string through. They were sometimes made of gold or silver and were worn as pendants, and their shape may have been derived from the predatory animal's teeth worn as pendants in prehistoric times. In fact, the Magatamas were the predominant, almost the only form of jewelry in Japan between 1000 BC and 600 AD. For the potential relationship of these Magatamas to the Siberian toli levels of the Buryats, see the section on Siberian Shamanism .

Magatamas have been in Japan since the Neolithic, especially around 300 BC. Ending Jōmon time BC can be proven. However, they are particularly common in the Kofun period of the 3rd to 6th centuries. AD century with their characteristic barrows. Together with the mirror and sword, they apparently played a central role in Shintoism and later in the imperial cult that was probably beginning at that time, after they had acquired a new meaning for the path of kami , in contrast to Buddhism . However, the material jade does not seem to have the actual symbolism (there are Magatamas also made of other materials), but rather the form inherited from the Neolithic ancestor cult that is still central to Shintoism today , which is remarkably also found in the yin-yang symbolism and which can certainly be described as two magatamas that fit on top of each other. In later periods, jade is a relatively rare material; This even applies to the nineteenth-century cabaret known as netsuke , whose miniature carvings were mostly made of wood and ivory, more rarely of horn, metal or lacquer. The classic, holy material of Japan was anyway bronze. The extensive lack of jade in Japan may be due to several factors:

- Long lack of deposits (they were only found in one place in Japan), which may have made jade extremely expensive.

- It is difficult to work with, which could have made it a second choice material given the tendency of Japanese art to adopt delicate and complex shapes. A separate art of jade carving, which is completely different from other carving techniques, apparently did not develop in Japan.

- But competition with China may also have played a role at the end of the first millennium AD. At that time, people increasingly closed themselves off from China and avoided everything Chinese or viewed it with contempt (an attitude that ultimately reached its gruesome climax in the 1937 Nanking massacre ). But jade was something very Chinese because of the cult that was woven around it in China. However, jade magatamas are still part of the emperor's insignia on the throne and are still often worn as an amulet, which is then seldom made of jade, so that the connection between jade and magatama can now be regarded as rather coincidental.

In Korea, too, the Magatamas can be found here and there in prehistoric places from the middle Mumun Pottery period 1500–300 BC. In the meantime, researchers have agreed that the Magatamas were brought from Japan to the south of Korea, where they are most commonly found (850–550 BC). They were particularly popular there at about the same time as in Japan during the Silla Kingdom (57 BC to 935 AD). They were worn on earrings and necklaces, but in particular they were used to decorate royal crowns, and in the area around Gyeongju one can find jade objects in the burial mounds of the Silla kings, especially on their ten crowns that have survived to this day (see Korean Art ). However, as in Japan, there is no longer any explicit cultic meaning of jade in Korea, which, as in Japan, was evidently avoided as a difficult-to-work material, especially since there was hardly any occurrence.

Shamanism of Siberia and the Ainu

The fact that there are mirrors of jade in shamanism in the Buryats of Siberia, which also occur in Buddhist practice, which influenced Siberian shamanism so intensely that one even speaks of lama shamans , possibly points to a North and East Asian Neolithic cultural continuum. The mirrors of the Buryats, called toli , are a symbol of the illusion of sensual perception and were also widespread among the other Turkic-Mongolian peoples . For the Buryats, however, they were an indispensable shaman attribute. Their symbolism includes, on the one hand, the ice hole through which the nomad fishes, but on the other hand, the gate through which the shaman can enter another world. The symbolism is possibly closely related to that of the torii gates of Japanese Shintoism, as well as to the mirror, which is the basic symbol of the kami alongside the magatama, whose comma form could have developed from it in a reductionist manner, and the sword.

The origin of the Siberian toli, on the other hand, possibly points to China, as bronze mirrors of a similar type often came from there. The complex symbolism of the mirror with a hole in the middle also resembles ancient Chinese cosmogonic ideas, such as those that appear in the yin-yang symbol, especially since the twelve-year cycle of the zodiac signs is present as an engraving on both the Chinese and the Buryat variants the animal symbolism was partially replaced. In the ancient Chinese burial ground of Jinggangshan near Nanking, which dates from around 3000 BC. Comes from the Hongshan culture , z. For example, over 600 individual objects were recovered, 47% of which were made of jade, many of them semicircular huang disks and round leaves with a hole, which anticipate the shape of the objects of the Liangzhu culture, which later became impressive as bi disks .

The strongly shamanic Ainu of Northern Japan (Hokkaido) made jade objects, such as bear sculptures as part of their old bear cult. The origin of this people is unclear, but there seems to be a connection to the Urals tribes in Siberia. This bear cult (it also existed in the Upper Paleolithic in Europe, as cave finds in France show) exist in a similar way among the Eskimos and the Aleutian people , and the small sculptures made there to this day are amazingly similar to those of the Ainu.

Pacific: Māori of New Zealand

The Māori developed a culture that differs from that of the rest of Polynesia and is similar to that of Melanesia . Nephrite occurs only on the west coast of the South Island of New Zealand on the edge of the andesite line. In the Maori language (reo māori) the area is also called Te Wai Pounamu - "The land of green stone water", or Te Wahi Pounamu - "The green stone place".

Jade (pounamu) includes a whole range of green minerals among the Māori, including nephrite, bowenite (in Māori: tangiwai ) and others. Greenstone was used by the Māori of New Zealand to make weapons, amulets and ornaments. Green stone carving is still a handicraft there, which often uses traditional forms of the Māori culture (māoritanga).

Typical objects of Māori art, besides ritual axes and amulets, are above all the tiki figures carved from nephrite , which were skillfully cut and passed on in the chief families. Such a Hei-tiki (too hot to tie around the neck and tiki first person) is a small, relief-like, embryonic-looking figure made of wood or stone with a sloping head and often large, penetrating eyes made of mother-of-pearl, which occasionally also, if larger and made of wood, used as a gable ornament or totem pole . It symbolizes either the first man or the crafty cultural hero Maui, which can be found in many Polynesian cultures, as an embryo. Thus, the jade , which is otherwise not used except for ceremonial purposes such as chiefs' axes (including the New Hebrides in New Caledonia, north of New Zealand ) seems to represent a very old cultic relationship to ancestor worship, similar to early Japan, Korea and China as well as in Siberian shamanism , possibly even to the Dema deity , because Maui not only created the land, but also brought fire to the people and typically dies trying to overcome the goddess of death. The Hei-Tiki gives its wearer mana , the power that is associated with fertility and creation, and which is also connected with the tapu (taboo), which prescribes certain social rules, as well as with the pure power of the universe.

The apparently cultic use of jade axes in ancient Europe (they were found in graves, see above ) and in other places around the world could represent a cultural-historical parallel based on similar spiritual ideas. The role of jade objects in the ritual Melanesian kula exchange network , which also includes New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and New Caledonia , must also be pointed out .

Other occurrences

Occasionally jade objects can also be found in other parts of the world. This applies above all to the ancient Orient, where gemstones were generally ascribed magical qualities, but less to the rarely available and often unknown jade, but to the "classic" stones such as sapphire, amethyst, lapis lazuli, chalcedony, rock crystal and so on. (Rubies were only known in the eastern Mediterranean after the 3rd century AD, samaragds were extremely rare, as were diamonds, which were hardly workable until the Middle Ages.)

- A serpentine stele is documented for the city of Ugarit in the Syrian-Canaanite region , which shows the king of the gods as a "gracious bull" receiving a libation from the king and thus represents the ancient Mediterranean bull cult as it was in the Anatolian Göbekli Tepe around 9500 BC. Is to be proven.

- In Crete , during the heyday of the Cretan-Minoan culture in the Second Palace Period between 1700 and 1450 BC, Vessels made of serpentine decorated with religious and sporting scenes are proven. Since this culture was central in the eastern Mediterranean and above all in the Aegean, the occurrence of jade objects in this large area cannot be ruled out. Trade connections with Egypt are proven.

- Abbot Suger's famous jade bowl, now in the Paris National Library, is believed to have come from Iran and is probably a product of the Persian Sassanids (AD 224-642 ), whose works of art can be found in museums all over the world. Since the Silk Road ran across this empire at that time, an import is the most likely source of this object, as jade art is otherwise not proven here and the perfection of this work requires a long craft tradition with a corresponding number of works that have emerged from it, but which it is known as far as possible not there.

- Central Asia, with the ancient Timurid rulership between the Chinese border, Mongolia and Iran and all the way down to Afghanistan, has one of the richest deposits of jade in its area, especially easily accessible rubble jade, and has accordingly developed rich jade carving. However, as far as can be ascertained, no forms and directions relevant to art or intellectual history or even rituals and philosophies, as in China, emerged, but only works of folk and small art used magically such as amulets, etc., in view of the strongly nomadic, still Sometimes the shamanic way of life of the local population is not surprising either. The Chinese soon began to source most of their jade from here along the Silk Road until the discovery of the rich deposits of Burma in the 18th century. However, it can be assumed that the jade art radiated from here to the outskirts of Iran, for example, but also to the India of the Mughals ( see above ) , without, however, ever assuming the prominent spiritual-religious value outside of shamanistic practices as in China or possibly also in Mesoamerica.

- Jade is not explicitly documented for the Byzantine Empire between 395 and 1453, but it could have been used occasionally because it came here via the Silk Road like other East Asian treasures such as silk, precious woods, tea, bronze, gold, pearls, etc. western branches in Constantinople, Palestine and Cairo ended. The same is certainly true for the later Islamic empires on the former Byzantine territory, such as the Ottoman Empire or the empire of the Mamelukes . However, it is questionable whether jade, the processing of which is very different from that of other gemstones and which requires great experience and special craftsmanship, arrived here as a raw product and not already as an artistic finished product on rings, bracelets, chains, etc.

Use as a gem stone

The most valuable jade variant is the so-called Imperial Jade or Kaiser Jade . It's extremely expensive, costing anywhere from $ 5,000 to $ 8,000 per carat in Hong Kong. One carat is 200 milligrams, one gram costs up to $ 40,000, roughly the same as a flawless, intensely blue-colored diamond of 1 carat (36,000 euros). For comparison: 1 g of gold costs around US $ 37.50 (as of February 1, 2013). The slightly transparent emerald green is typical of the imperial jade.

Processing and maintenance

Although apparently only slightly above medium-hard ( hardness scale 6.5–7), jade is difficult to work with because of its delicate consistency, but especially because of its great toughness (tenacity), mainly because its cleavage cannot be recognized beforehand and it breaks like a shell. It is therefore said of the jade craftsmen in China that they first felt a piece of jade for years and explored its consistency before they began to carve and grind it (with sand). Jade cannot simply be carved with a knife like wood, but has to be brought into the desired shape in time-consuming work steps using disc saws, contour drilling and grinding with simple tools that, apart from the material, have basically not changed until today. Earlier and as early as the Neolithic Age, massive drill heads made of stone or hardwood, but also tubular drill bits made of bone and the very hard bamboo, which even replaced stone tools east of the Movius line in East Asia, were used as drills . They were rotated with the help of a bowstring looped around them. Quartz sand (hardness 7) was often used as an abrasive, which was then poured into the drilling joint with water and grease. The harder the abrasive, the more precise the hole was.

Jadeite is sensitive to heat. This stone is rather insensitive to acids, but becomes highly sensitive if it has come into contact with heat beforehand. This means that all acids, acid mixtures (brew), galvanic baths, etc. must be strictly avoided. Exposed jadeite must be protected from spotlighting or strong sunlight. It must not be cleaned with ultrasound. Some silver dips leave stains on the stone surface. For silver frames with jadeite, silver cleaning cloths are more advisable.

Imitations and manipulations

For economic reasons, attempts have always been made to incorporate new minerals and rocks under the term jade. Probably the best known and most interesting case of an unintended formation of an imitation today is probably the noble serpentine (“China jade”, “new jade”). For mineralogical morphogenesis see under the individual minerals.

Serpentine not only looks similar to jade, it even occurs in the same deposits as jadeite and nephrite. However, the material is significantly softer (hardness 4) and has a much lower toughness than jade. As serpentine is much easier to work with it, it has become the preferred jade substitute in recent years. This “noble serpentine” is also mined and processed in Austria , for example (in the town of Bernstein in Burgenland). The use of noble serpentine in China can also be proven over a period of 8000 years. The term "new jade" is therefore a trick and not due to an alleged rediscovery of noble serpentine. However, this trick seems originally to be based on a translation error: What is now called “new jade” is a type of noble serpentine, which is mined in Xiu Yan in northeast China. That is why this mineral is called Xiu-Yu in China (after the city of Xiu-Yan ). In some catalogs and mineral lists, the “new jade” is therefore referred to as Xin-Yu - xin is the Chinese word for “new”. The u in Xiu became an n , so that Xiu-Yu erroneously resulted in Xīn-Yù (新 玉), which in turn was correctly translated as “new jade”. Perhaps it was also because Xiu is not really translatable, since it is part of a city name.

Other jade imitations include:

- Prasem or "African Jade"

- various chlorites under the trade names "Marble Bar Jade" or "Pilbara Jade"

- Since 1998 hydrofluorite has been offered under the trade name Lavender Jade as Smithsonite and jade imitations.

- the green beam Stone ( Smaragdite -Jade)

- green grossular from South Africa (Transvaal jade)

- brown Vesuvian from California ( Vesuvian jade , californite )

- Serpentine from China (Serpentine Jade)

- Ophicalcite , a type of serpentine marble with a breccia structure, which comes from Greece among others , is often sold under the name “Connemara” or “Verde antique”.

- greenish sillimanite from Burma and Sri Lanka (sillimanite jade).

Yellow aragonite is used as a substitute for the rare yellow jadeite . Colored chalcedony and artificial products made of colored glass (trade name "Siberian jade") are also used as imitations. They all differ from real jadeite in hardness, specific weight and light refraction (and above all in price).

See also

Sources and literature

reference books

- Wilhelm Karl Arnold , Hans Jürgen Eysenck , Richard Meili (Hrsg.): Lexicon of Psychology. 3 volumes. 11th edition. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1993, ISBN 3-451-23129-8 .

- Gerhard J. Bellinger : Lexicon of Mythology: over 3000 keywords to the myths of all peoples. Nikol, Hamburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-86820-138-3 . (formerly: Knaurs Lexikon Mythologie )

- Brockhaus encyclopedia . 24 volumes. 19th edition. Brockhaus, Mannheim 1986–1994, ISBN 3-7653-1100-6 .

- Encyclopedia Britannica . 32 volumes. 15th edition. 1993, ISBN 0-85229-571-5 (English).

- Walter Jens (ed.): Kindlers new literature lexicon . Volume 19: Anonyma, Essays. Kindler, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-463-43200-5 .

- Kurt Hennig (Ed.): Jerusalem Bibellexikon . 4th edition. Hänssler, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-7751-2367-9 .

- Thomas Patrick Hughes: Lexicon of Islam . Orbis, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-925037-61-6 / ISBN 3-572-01016-0 .

- A. Th. Khoury, L. Hagemann, P. Heine (Eds.): Islam-Lexikon. History - ideas - design. (= Herder Spectrum. Volume 4036). 3 volumes. Herder, Freiburg 1991, ISBN 3-451-04036-0 .

- Kluge: Etymological dictionary of the German language . Edited by E. Seebold. 24th edition. de Gruyter, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-11-017472-3 .

- K. Koch, E. Otto, J. Roloff, H. Schmoldt (eds.): The Lexicon for the Bible. Old and New Testament. Tosa, Stuttgart 2004.

- Lexicon of Art. 7 volumes. 2nd Edition. Seemann, Leipzig 2004, ISBN 3-86502-084-4 .

- A. Negev: Archaeological Bible Dictionary. 2nd Edition. Hänssler, Stuttgart 1991, ISBN 3-7751-1685-0 .

- Pschyrembel Dictionary Naturopathy . de Gruyter, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-11-014276-7 .

Monographs and compilations

Unless stated in the individual references, the exact page numbers were mostly not reproduced because all these works, as far as secondary literature, have very precise subject indexes and the page numbers are also different in different editions and editions. Primary works such as those by Anna Freud, Max Weber or Ad. E. Jensen, on the other hand, are important as a whole and not just page by page.

- Al-Kaswini (Al-Qazwînî Zakariyyâ 'ibn Muhammad ibn Mahmud Abu Yahyâ): The wonders of heaven and earth. (= Library of Arabic Classics. Volume 11). Edition Erdmann, Thienemann Verlag, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-522-62110-7 , pp. 94-143. (OA publ. 1276/77)

- J. Baines, J. Málek: World Atlas of Ancient Cultures: Egypt. History, art, forms of life. Christian Verlag, Munich 1980, ISBN 3-88472-040-6 .

- Caroline Blunden, Mark Elvin: World Atlas of Ancient Cultures: China. History, art, forms of life. Christian Verlag, Munich 1989, ISBN 3-88472-151-8 .

- R. Cavendish, TO Ling: Mythology. An illustrated world history of mythical-religious thought. Christian Verlag, Munich 1981, ISBN 3-88472-061-9 .

- Chen Lie: The ancestor cult in ancient China. In: Ancient China. P. 36ff.

- MD Coe (eds.), D. Snow, Elizabeth Benson: World Atlas of Ancient Cultures: America Before Columbus. History, art, forms of life. 2nd Edition. Christian Verlag, Munich 1985, ISBN 3-88472-091-0 .

- M. Collcutt, M. Jansen, Isao Kumakura: World Atlas of Ancient Cultures: Japan. History, art, forms of life. Christian Verlag, Munich 1989, ISBN 3-88472-151-8 .

- F. Comte: Myths of the World. WBG, Darmstadt 2008, ISBN 978-3-534-20863-0 .

- T. Cornell, J. Matthews: World Atlas of Ancient Cultures: Rome. History, art, forms of life. Christian Verlag, Munich 1982, ISBN 3-88472-075-9 .

- B. Cunliffe (Ed.): Illustrated pre- and early history of Europe. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-593-35562-0 .

- On the road to the afterlife. In: Der Spiegel. 48/2008.

- IES Edwards: Tutankhamun. The grave and its treasures. Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 1978, ISBN 3-7857-0211-6 , p. 145.

- Anna Freud: The ego and the defense mechanisms. Kindler Verlag, Munich 1964.

- S. Freud: Totem and Taboo. Some similarities in the soul life of savages and neurotics. 9th edition. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt 2005, ISBN 3-596-10451-3 . (OA 1912/13)

- Sir Allan Gardiner: Egyptian Grammar - Being an Introduction in the Study of Hieroglyphs. 2nd Edition. Oxford University Press, London 1950.

- B. Gascoigne: The Mughals. Splendor and greatness of Mohammedan princes in India. Prisma Verlag, Gütersloh 1973, ISBN 3-570-09930-X .

- Valentina Gorbatcheva, Marina Federova: The peoples of the far north. Art and culture of Siberia. Parkstone Press, New York 2000, ISBN 1-85995-484-7 .

- W. Haberland: American archeology. History, theory, cultural development. BBG, Darmstadt 1991, ISBN 3-534-07839-X .

- R. Hochleitner: Photo Atlas of Minerals and Rocks. 2nd Edition. Gräfe and Unzer, Munich 1981, ISBN 3-7742-2423-4 .

- Ad. E. Jensen: Myth and cult among primitive peoples. Religious studies. 2nd Edition. dtv, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-423-04567-1 .

- G. Johnson: World Atlas of Ancient Cultures: India and Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka. History, art, forms of life. Christian Verlag, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-88472-271-9 .

- E. Kasten (Ed.): Shamans of Siberia. Mage - Mediator - Healer. Reimer, Berlin / Lindenmuseum Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-496-02812-3 .

- Andrea Keller: Cosmos and Cultural Order in Early Chinese Mythology. In: Ancient China. P. 136ff.

- D. Kuhn: Dead rituals and burials in ancient Chinese. In: Ancient China. P. 45ff.

- Kulturstiftung Ruhr Essen Villa Hügel (ed.): The old China. People and gods in the Middle Kingdom 5000 BC Chr. - 220 AD. Exhibition catalog. Hirmer Verlag, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-7774-6640-9 , catalog part no. 11, 16-20, 34-36, 48-50, 53-56, 69-71, 80.

- Elsy Leusinger (ed.): Ropylänen art history. Suppl .: Art of the primitive peoples. Ullstein, Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-549-05666-4 .

- P. Levi: World Atlas of Ancient Cultures: Greece. History, art, forms of life. Christian Verlag, Munich 1980, ISBN 3-88472-041-4 .

- D. Matthew: World Atlas of Ancient Cultures: Africa. History, art, forms of life. Christian Verlag, Munich 1983, ISBN 3-88472-042-2 .

- Machteld Mellink, J. Filip: Early stages of art. (= Propylaea art history. Volume 14). Propylaeen Verlag, Berlin 1985, ISBN 3-549-05666-4 .

- H. Müller-Karpe: Handbook of Prehistory. First volume: Paleolithic. 2nd Edition. CH Beck, Munich 1977, ISBN 3-406-02008-9 .

- H. Müller-Karpe: Basics of early human history. Volume 1-5. Theiss Verl, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-8062-1309-7 .

- R. Nile, Ch. Clerk: World Atlas of Ancient Cultures: Australia, New Zealand and the South Pacific. History, art, forms of life. Christian Verlag, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-88472-291-3 .

- M. Okrusch, S. Matthes: Mineralogy. 7th edition. Springer, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-540-23812-3 .

- E. Probst: Germany in the Stone Age. Hunters, fishermen and farmers between the North Sea coast and the Alps. Bertelsmann, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-570-02669-8 .

- R. Riedl: Culture - late ignition of evolution. Answers to questions about evolution and epistemology. Piper Verlag, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-492-03114-5 .

- F. Robinson: World Atlas of Ancient Cultures: Islam. History, art, forms of life. Christian Verlag, Munich 1982, ISBN 3-88472-079-1 .

- W. Rodzinski: China. The Middle Kingdom and its history. Busse Seewald, Herford 1987, ISBN 3-512-00745-7 .

- Roemer and Pelizaeus Museum Hildesheim (ed.): Splendor and fall of ancient Mexico. The Aztecs and their predecessors. With contributions by W. Haberland, EM Moctezuma, Viola König, Emily Umberger, W.-G. Thieme, Eva Eggebrecht, Ch.F. Feest and HB Nicholson. Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1986, ISBN 3-8053-0908-2 .

- Roemer and Pelizaeus Museum Hildesheim (ed.): Splendor and fall of ancient Mexico. The Aztecs and their predecessors. Exhibition catalog. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1986, ISBN 3-8053-0908-2 , cat. Nos. 3–9, 126, 156, 196, 207, 223, 257, 275, 318, 344, 345, 349, 355.

- K. Schmidt: You built the first temple. The enigmatic sanctuary of the Stone Age hunters. The archaeological discovery at Göbekli Tepe. CH Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-53500-3 .

- H. Schmökel (ed.): Cultural history of the ancient Orient. Mesopotamia. Hittite Empire, Syria - Palestine, Urartu. Weltbild Verlag, Augsburg 1995, ISBN 3-89350-747-7 .

- W. Schumann: Precious stones and gemstones. 13th edition. BLV Verlag, 1976/1989, ISBN 3-405-16332-3 .

- A. Sherratt (Ed.): The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Archeology. Christian Verlag, Munich 1980, ISBN 3-88472-035-X .

- T. Ju Sem, MV Fedorova: Shamanism and Buddhism among the peoples of Siberia. In: Box: Shamans of Siberia. P. 164ff.

- Brunhild Staiger (Ed.): China. Nature, history, society, politics, state, economy, culture. Erdmann, Tübingen 1980, ISBN 3-7711-0330-4 .

- St. M. Stanley: Historical Geology. 2nd Edition. From the American by Volker Schweizer. Spektrum Akad. Verlag, Heidelberg 2001, ISBN 3-8274-0569-6 .