Monte Albán

| Prehistoric city Monte Albán |

|

|---|---|

|

UNESCO world heritage |

|

|

|

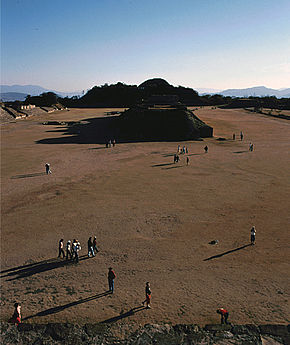

| Monte Albán with the central pyramid in the main square |

|

| National territory: |

|

| Type: | Culture |

| Criteria : | i, ii, iii, iv |

| Reference No .: | 415 |

| UNESCO region : | Latin America and the Caribbean |

| History of enrollment | |

| Enrollment: | 1987 (session 11) |

Coordinates: 17 ° 2 ′ 38 ″ N , 96 ° 46 ′ 6 ″ W.

Monte Albán ( Spanish: white mountain) was the capital of the Zapotecs and is 10 km away from the city of Oaxaca de Juárez in the state of Oaxaca ( Mexico ) of the same name . Monte Albán is located 2000 m above sea level on an artificially flattened hilltop and was the religious center of the Zapotecs, later the Mixtecs . Its heyday is between 300 and 900 AD. According to previous knowledge, the beginning of the settlement of Monte Albán was in the 8th century BC. Extensive remains of residential and cult buildings, an observatory, burial chambers with sculptures and wall paintings have been preserved. In 1987 Monte Albán was included in the UNESCO World Heritage Site . On March 30, 2015, the memorial was included in the International Register of Cultural Property under the special protection of the Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict .

history

The first settlement of the fertile Oaxaca Valley, a plateau with numerous caves, is believed to have occurred between 800 and 300 BC. Adopted by Olmec settlers. Writing and numerical representation are known from this first period (600–300 BC). From 300 BC New settlers migrated to the valley and mingled with the ancestral population. On the basis of figure vessels with depictions of gods, between 300 and 500 AD, cultural relationships with Teotihuacán can be clearly demonstrated.

In the 5th and 6th centuries, Monte Albán reached the height of its power. Up to 30,000 people lived on the slopes of the mountain during this time. From 700 the city then lost its importance radically and was finally completely abandoned around 950. After that it was only used as a burial place. The additions found in the tombs show a clear Mixtec influence since the 14th century . The famous grave number 7 with its unique accumulation of precious additions made of gold, silver and jade also dates from this time .

In its last phase before the Spanish conquest, the old burial grounds in Monte Albán were used by the Mixtecs for burials for their elite from around 1250. The necropolis expanded while the Zapotec culture developed in Mitla and smaller towns in the Oaxaca Valley during the Monte Albán IV period. In 1458 the Aztecs occupied the Oaxaca Valley including Monte Albán.

Timetable

| year | event |

|---|---|

| around 800-300 BC Chr. | first settlement by Olmecs |

| 300 BC Chr. - Chr | Resettlement of Monte Albán |

| Chr. Born-900 | Construction of the step pyramids on terraces by the Zapotecs |

| 900-1250 | Planting the graves; Zapotecs give up Monte Albán |

| 1250-1521 | Mixtec immigrate |

| 1458 | Aztecs under Moctezuma I (1440–69) occupy Monte Albán |

| 1521 | Spanish conquerors take Oaxaca |

| 1987 | Monte Alban is the UNESCO - World Heritage Site |

Discovery story

The impressive ruins of Monte Albán, visible from all sides of the Oaxaca Valley, have attracted visitors and researchers since colonial times. Among them, Guillermo Dupaix explored the place from the early 19th century. JM Arcía published a description in 1859 and AF Bandelier also visited and published further descriptions in the 1890s. The first intensive archaeological research was undertaken in 1902 by Leopoldo Batres, General Inspector of Monuments, on behalf of the government of the Mexican dictator Porfirio Diaz . Nevertheless, large-scale scientific excavations did not take place until 1931 under the direction of the Mexican archaeologist Alfonso Caso . For the next eighteen years, Caso and his colleagues Ignacio Bernal and Jorge Acosta dug inside the monumental center. Much of what is now open to the public was reconstructed at that time.

In addition to numerous excavations of residential and ceremonial buildings and structures and hundreds of graves and burial mounds, the creation of a ceramic chronology of the phases Monte Albán I to V - and thus the period between 500 BC - remains. And the end of the post-classical period in 1521 AD - a lasting achievement.

The prehistoric and human ecological excavation campaign initiated by Kent Flannery of the University of Michigan in the late 1960s focused on exploring the periods that followed the founding of Monte Albán. During the following two decades, the campaign documented the development of socio-political complexity in the Oaxaca Valley, beginning with the first Archaic period (approx. 8000–2000 BC) to the Rosario phase (700–500 BC). ), which followed Monte Albán and set the stage for the later founding and development. In this context, the special abilities of Flannery's work in Oaxaca lie in his extensive excavations of the important formative center of San José Mogote in the Etla branch of the valley, an excavation campaign that he carried out jointly with Joyce Marcus of the University of Michigan (Flannery and Marcus 1983 , 1996).

Another important step in understanding the history of the settlement of Monte Albán was achieved with the prehistoric settlement patterns in the Oaxaca Valley excavation campaign started by Richard Blanton and some colleagues in the early 1970s. Thanks to their intensive research and mapping of the entire area, the real extent and size of Monte Albán beyond the limited area explored by Caso (Blanton 1978) became known. In the years that followed, the research campaign, led by Blanton, Gary Feinman, Steve Kowalewski, Linda Nicholas, and others, was extended to nearly the entire valley, providing an invaluable wealth of data on the region's changing settlement patterns from the early days to the arrival of the Spanish in 1521 (Blanton et al. 1982, Kowalewski et al. 1989) unearthed.

buildings

Several pyramids , temples and tombs as well as significant reliefs and sculptures were uncovered in Monte Albán . A Mesoamerican ball game is regularly performed on the large square in the middle of the facility .

The monumental center of Monte Albán is the main square, which measures around 300 × 200 m. The main ceremonial and residential structures are around it or in its immediate vicinity and most have been researched and restored by Alfonso Caso and his colleagues. In the north and south, the main square is bounded by large platforms that can be accessed from the square via monumental stairs. On its eastern and western sides, the square is bounded by a number of smaller hill platforms on which there are temples and houses of the elite, as well as one of two well-known ball courts. Ball playground, most of the reliefs and painted burial chambers date from the Monte Albán III period (200-900 AD). During this period, themes from Teotihuacán were combined in frescoes with hieroglyphics and symbols from the Zapotecs. The center of the square is taken up by a north-south backbone of hills and also served as platforms for cult structures.

A characteristic of Monte Albán is the large number of monuments made of worked stones that one encounters in the square. The earliest examples are the so-called Danzantes (Spanish = dancers), found mainly in the vicinity of Building L, showing naked men in crooked and twisted poses, some of them genitally mutilated. The nineteenth century view of them portraying dancers is largely discredited today. These relief plates , which are among the earliest of the Monte Albán I period (approx. 600-100 BC), clearly show tortured , sacrificed prisoners of war , some of them identified by name and some depicted chiefs of the rival settlement centers and villages, those of Monte Albán were occupied. Over 300 Danzantes steles, which are reminiscent of Olmec representations and show the oldest hieroglyphs in Mesoamerica, have been recorded to this day and some of the better preserved can be viewed in the museum on site.

Another type of stone was found near building J in the center of the main square, a building that is characterized by an unusual, arrow-like outline and differs in its orientation from most of the other structures in the place. Set in the walls of the building are over 40 large chiseled slabs, which are dated to the Monte Albán II phase and represent place names, occasionally accompanied by additional characters and in many cases characterized by heads hanging upside down. Alfonso Caso was the first to identify these rocks as signs of conquest, which probably enumerate places that the elite of Monte Albán claimed to have been conquered and / or controlled. Some of the locations listed on the panels in Building J have been tentatively identified and in one case (the Cañada de Cuicatlán region in the northern Oaxaca Valley) the Zapotec conquest has been confirmed by archaeological research and excavations (Redmond 1983; Spencer 1982 ).

Archaeological site

The Monte Albán Ceremonial Center is located on an approximately 250 by 750 meter large, rectangular, artificially created plateau , which rises approximately 400 m above the valley floor to 1940 m above sea level. In addition to the monumental religious center, the place is characterized by several hundred artificial terraces and dozens of piles of burial mounds along the entire ridge and its surrounding flanks. The archaeological ruins on the nearby Atzompa and El Gallo hills to the north are also counted as parts of the ancient city.

The importance of Monte Albán, one of the oldest cities in Mesoamerica, is based on its role as the socio-political and economic center of the towering Zapotecs for almost a millennium. Founded at the end of the middle formative period (approx. 500-100 BC), Monte Albán experienced its heyday as the capital of a far-reaching, expansionist state during the late formative period (approx. 100 BC - 200 AD) when it ruled the highlands of Oaxaca and had relations with other regional states in Mesoamerica, such as Teotihuacán in the north (Paddock 1983, Marcus 1983). The city lost its political importance at the end of the late classical period (approx. 500 - 700 AD) and was largely abandoned shortly afterwards. Small-scale resettlement and use of earlier structures and graves as well as ritual pilgrimages characterize the archaeological history of the place during the colonial period.

The origin of today's place name is unclear. The suggestions range from a suspected corruption of the original Zapotec name Dani Baá , Danibaan or Danipaguache (Zapotec = holy mountain) to a reference to a Spanish soldier named Montalbán in the colonial period to the Italian Alban Mountains . The ancient Zapotec place name is unknown because the Zapotecs abandoned the city centuries before the first available ethno-historical record. The Mixtec gave the place the name Yúcu-cúi (Mixtec = Green Mountain). The Aztecs called Monte Albán Ocelotepec or Jaguar Mountain .

According to Blanton's investigation of the archaeological site, Monte Albán appears to have existed before 500 BC. BC, the end of the Rosario pottery phase, to have been uninhabited. At that time, the main settlement area of the valley was San José Mogote , which served as the center of the chiefdom in the northern Etla tributary valley (Marcus and Flannery 1996). Possibly three or four smaller chiefs' centers controlled other sub-regions of the valley including Tilcajete in the southern Valle Grande and Yegüih in the Tlaco lula in the eastern side valley. Competition and war appear to characterize the Rosario phase, and regional exploration data suggest the existence of an unpopulated buffer zone between the San José Mogote chiefdom and those to the south and east (Marcus and Flannery 1996). Within this no man's land, Monte Albán was founded at the end of the Rosario period. It quickly reached an estimated population of about 5200 people at the end of the subsequent Monte Albán Ia phase (approx. 300 BC). This remarkable increase in population was accompanied by a parallel population decline in San José Mogote and its neighboring satellite settlements, which make it likely that the chief elite were directly involved in the founding of the future Zapotec capital. The rapid increase in population and the change in settlement from a scattered settlement to a central city in a previously unpopulated area was described by Marcus and Flannery (Marcus and Flannery 1996, pp. 140-146) as Monte Alban synoicism in allusion to a comparable phenomenon Mediterranean called during ancient times. Although it was initially assumed (Blanton 1978) that a comparable process of giving up in large numbers and the consequent participation in the founding of Monte Albán would also have to be observed in the other chiefs' seats such as Yegüih and Tilcajete, it now seems unlikely in the case of the latter . One of the most recent excavation campaigns, led by Charles Spencer and Elsa Redmond of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City , showed that the place was not abandoned, but that it was populated during the early Monte Albán I period (approx. 500- 300 BC) and the late Monte Albán I period (approx. 300-100 BC) even grew significantly and possibly actively resisted inclusion in the increasingly powerful Monte Albán state (Spencer and Redmond 2001).

At the beginning of the last formative period (Monte Albán II phase, approx. 100 BC - 200 AD), Monte Albán was one of the largest with an estimated population (Marcus and Flannery 1996, p. 139) of 17,200 inhabitants Cities of Mesoamerica at that time. With growing political power, Monte Albán expanded militarily through occupation and colonization in various areas outside the Oaxaca Valley including the Cañada de Cuicatlán in the north and the Ejutla and Sola de Vega side valleys in the south (Balkansky 2002; Spencer 1982; Redmond 1983; Feinman and Nicholas 1990). During this period and the following Early Classical period (Monte Albán IIIA phase, approx. 200 - 500 BC), Monte Albán was the capital of the most important regional polis , which exerted a dominant influence in the Oaxaca Valley and over large parts of the Oaxaca highlands. As previously mentioned, there is evidence of high-level contacts between the elites of Monte Albán and the powerful city of Teotihuacán in central Mexico, where archaeologists identified a neighborhood of ethnic Zapotecs from the Oaxaca Valley (Paddock 1983). During the late classical period (Monte Albán IIIB / IV, approx. 500 - 1000 AD) the influence of the place inside and outside the valley decreased, with former members of the elite of Monte Albán exercising their autonomy in individual other places such as Cuilapan and Zaachila in the Valle Grande and Lambityeco, Mitla and El Palmillo in the eastern Tlacolula side valley, secured. The latter is the subject of an excavation campaign by Gary Feinman and Linda Nicholas of the Chicago Field Museum of Natural History (Feinman and Nicholas 2002). At the end of this period (900-1000 AD), the old capital was largely abandoned and the once powerful state of Monte Albán was replaced by dozens of competing polis such as Zaachila, Yagul , Lambityeco, and Tehuantepec - a development that began with the Spanish conquest found its end.

Artifacts

Many of the artefacts excavated in Monte Albán from more than a century of archaeological research can be viewed in the Mexican National Museum of Anthropology and the Regional Museum of Oaxaca in the former Santo Domingo de Guzmán convent in Oaxaca. These museums own many of the objects that were discovered by Alfonso Caso in Monte Albán in 1932 in grave 7, a Zapotec grave of the classical period, which was used in the post-classical period for burials of members of the Mixtec elite. Her burial was accompanied by some of the most spectacular offerings ever found in America (Caso 1932). As the Mixtecs mastered advanced metalworking , there were silver and gold objects, pieces of jewelry with gemstones and bone carvings with hieroglyphs and calendar inscriptions among the offerings. Their multicolored ceramics in the style of their illuminated manuscripts prove the change of power on Monte Albán, which was not settled by the Mixtecs.

Monte Albán is now a popular tourist destination in Oaxaca and has a small on-site museum that exhibits mostly chiseled stones.

See also

literature

- Andrew K Balkansky: The Sola Valley and the Monte Albán State. A Study of Zapotec Imperial Expansion. (= Memoirs No. 36, Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan ). Ann Arbor 2002, ISBN 0-915703-53-X .

- Leopoldo Batres: Exploraciones en Monte Albán. Casa Editorial Gante, México 1902.

- Richard E Blanton: Monte Albán: Settlement Patterns at the Ancient Zapotec Capital. Academic Press, New York City 1978, ISBN 0-12-104250-2 .

- Richard E. Blanton, Gary M. Feinman, Stephen A. Kowalewski, Linda M. Nicholas: Ancient Oaxaca: the Monte Albán State. Cambridge University Press, London 1999, ISBN 0-521-57787-X .

- Richard E. Blanton, Stephen A. Kowalewski, Gary M. Feinman, Jill Appel: Monte Albán's Hinterland, Part I: Prehispanic Settlement Patterns of the Central and Southern Parts of the Valley of Oaxaca, Mexico. (= Memoir 15, Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan ). Ann Arbor 1982, ISBN 0-932206-91-3 .

- Alfonso Caso: Monte Albán, richest archaeological find in the Americas. In: National Geographic Magazine. LXII, 1932, pp. 487-512.

- Michael D. Coe, Dean Snow, Elizabeth Benson: Atlas of Ancient America. Facts on File, New York City 1986, ISBN 0-8160-1199-0 .

- Gary M. Feinman, Linda M. Nicholas: At the Margins of the Monte Albán State: Settlement Patterns in the Ejutla Valley, Oaxaca, Mexico. In: Latin American Antiquity. 1, 1990, pp. 216-246.

- Gary M. Feinman, Linda M. Nicholas: Houses on a Hill: Classic Period Life at El Palmillo, Oaxaca, Mexico. In: Latin American Antiquity. 13, 2002, pp. 251-277.

- Stephen A. Kowalewski, G. Feinman, L. Finsten, R. Blanton, L. Nicholas: Monte Albán's Hinterland, Part II: The Prehispanic Settlement Patterns in Tlacolula, Etla and Ocotlán, the Valley of Oaxaca, Mexico. (= Memoir 23, Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan ). Ann Arbor 1989, ISBN 0-915703-18-1 .

- Joyce Marcus: Teotihuacan Visitors on Monte Alban Monuments and Murals. In: KV Flannery, J. Marcus (Eds.): The Cloud People. Academic Press, New York City 1983, ISBN 0-12-259860-1 , pp. 175-181.

- Joyce Marcus, Kent V. Flannery: Zapotec Civilization: How Urban Society Evolved in Mexico's Oaxaca Valley. Thames and Hudson Publishers, London 1996, ISBN 0-500-05078-3 .

- John Paddock: The Oaxaca Barrio at Teotihuacan. In: KV Flannery, J. Marcus (Eds.): The Cloud People. Academic Press, New York City, 1983, ISBN 0-12-259860-1 , pp. 170-175.

- Elsa M. Redmond: A Fuego y Sangre: Early Zapotec Imperialism in the Cuicatlán Cañada. (= Memoir 16, Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan ). Ann Arbor 1983, ISBN 0-932206-97-2 .

- Charles S. Spencer: The Cuicatlán Cañada and Monte Albán: A Study of Primary State Formation. Academic Press, New York City / London 1982, ISBN 0-12-656680-1 .

- Charles S. Spencer, Elsa M. Redmond: Multilevel Selection and Political Evolution in the Valley of Oaxaca, 500-100 BC In: Journal of Anthropological Archeology. 20, 2001, pp. 195-229.

Web links

- Entry on the UNESCO World Heritage Center website ( English and French ).

- Map with views of ruins ( Memento from September 28, 2008 in the web archive archive.today )

- Treasures of the World ( Memento from August 28, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

Individual evidence

- ↑ International Register of Cultural Property under Special Protection. (PDF) UNESCO, July 23, 2015, accessed on June 2, 2016 .

- ↑ a b c Glyn E. Daniel: Encyclopedia of Archeology. Bergisch Gladbach 1996, ISBN 3-930656-37-X , p. 336.