Mesoamerican ball game

The Mesoamerican ball game was both a game and a ritual for the Mesoamerican peoples ( Aztec , Maya , Mixtec , Toltec , Totonac and Zapotec ) in the pre-Columbian period. For a long time the Olmecs were considered to be the inventors of the ball game, but in view of a ball playground from around 1400 BC that was discovered at the end of the 20th century in Paso de la Amada on the Pacific coast . BC (cf. Mokaya culture ) - much again uncertain. The close connection between cultic ritual, arbitration and play / sport played an important role until the Europeans conquered the continent (from 1519) and the widespread cultural destruction. It is reported that Emperor Charles V was shown an Aztec ball game team by Hernán Cortés . The Mesoamerican ball game thus became a not unimportant factor in the development of European ball games. Variants of the Mesoamerican ball game are still played today. In the Pacific coastal regions of Mexico, Sinaloa and Nayarit , this is the ulama, for example .

It is interesting to note that neither in Teotihuacán , one of the largest and most important cities in Mesoamerica, nor in the diverse cultural sites of North and South America were ball playgrounds found. In Teotihuacán, however, some ball players can be seen in the mural of the “ Paradise of Tlaloc ”, although the subject is treated here as a leisure activity.

Spelling

It was only since the last quarter of the 20th century that it became possible to read various Mesoamerican scriptures . That is not yet certain knowledge, so that there are always re-evaluations of individual characters. This applies in particular to the grammar, so that the presentation here may only be regarded as provisional.

Aztecs

In the Aztec script, the glyph tlachtli stands for a ball playground. The ball is called olli (sometimes inaccurately spelled ulli ) just like its material, which is where the Spanish word for rubber hule comes from. It is a natural product, which was probably produced by the Panama rubber tree ( Castilla elastica ) . The game is called ollamaliztli , a combination of olli and tlama (“to hunt”, “to take prisoners”) with suffixes that make up nouns.

Maya

| Maya | translation | used glyph |

|---|---|---|

| pitzah- | To play ball ( intr. Verb ) | pi-tza-ha |

| pitzal | Ball player | pi-tzi-la |

| pitzil | ball-playing ( adj. ) | pi-tzi-li |

| pitzil | beautiful, admiring ( adj. ) | pi-tzi-li |

| pitzi | Ball game ( sub. ) | pi-tzi |

| alaw, halab ', halaw | Place to play ball | 'a-la-wa |

| kab'al pitzal | Title: "Earth-like Ballplayer" | ka-b'a-la-pi-tzi-la |

The glyph pi-tzi-li (purely syllabic notation) is used, as is typical for Maya , both for the adjective "ball playing" and for "beautiful", "admiring". The rather sacred character of the game is shown in the fact that the noun pi-tzi-la occurs in titles and the ball game of the divine twins Hunahpú and Ixbalanqué against the powers of the underworld ( xibalba ) in the mystical book of the Quiché -Maya, the Popol Vuh , has great importance.

architecture

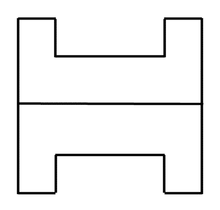

So far, more than 1500 ball courts have been discovered in the Mesoamerican ruined cities; even smaller towns sometimes had several ball courts. The best preserved or restored buildings are now in Copán , Iximché , Monte Albán , Uxmal , Zaculeu and Chichén Itzá , the latter being the largest with a length of 166 m and a width of 68 m in the side wings. According to some researchers, the aim of the game was to push a ball through a ring placed in the middle of the central area of the playing field at a certain height (2.50 to 3.50 m) or through a certain ring - not ring-shaped, but mostly full round - to hit markers that probably symbolized the sun. In central Mexico one often finds elongated, narrow and laterally open playing fields (e.g. Yohualichan ), whereas in the south and on the Yucatán peninsula, playing fields in "H" shape predominate, with the two end pieces of which the ring or the Marking stone could not or only with difficulty be reached, possibly other rules applied. In most of the ball playgrounds in the south, the middle playing field is accompanied by sloping sides, from which the ball could jump back into the field; Entering this incline was probably taboo for players and spectators.

game

regulate

During the three millennia in which the game was played, the rules - also depending on the location - changed again and again: The number of participating players varied, as did the parts of the body with which the ball could be touched, and the consequences of a lost game - For a long time it was believed that the plaything associated with the sun should not touch the ground. It is an open question whether it was a game between two opposing teams in classical times, or whether all players worked together on the common goal of keeping the ball in the air, because in all depictions of ball players it is noticeable that the Ball never lies on the ground.

Social relevance

The social significance of the game also changed - reliefs in Chichen Itza and El Tajin suggest that it ended in human sacrifice , but such depictions are absent on most ball courts . The four steles of Bilbao rather suggest that through the game a connection between this world and the other world could be established. In addition, there are reports from Spanish times, according to which the outcome of wars was decided by a game, prisoners of war played for their survival, wagered on great values or that - probably only in the late period - it was the focus of popular festivals. The Dominican Diego Durán gives a very detailed description of the game in the post-classical period .

Yoke stones

In Mexico and Mesoamerica, a large number of extremely richly reliefed “U” -shaped yoke stones (yugos) were found, the connection with which the ball game was only recognized late. They were placed around the hips of the ball players and tied with ribbons on the open side. It is possible that the stones, which weigh about 15-20 kg, were only used for ceremonial purposes and were exchanged for lighter girdles made of fur, deerskin or wrapped fabric for the actual game. However, some researchers are of the opinion that the hip stones - perhaps wrapped with padding - were also worn during the game.

dress

The ball players wear a cloth tied up between their legs under the hip belt or hip stone, sometimes also a jaguar skin . The feet are in high sandals. The hands are sometimes protected by a kind of glove ( El Baúl , stele 5); only elbows and shoulders, which were probably essential for playing the ball, remained unprotected. An elaborate headdress can often be seen on the depictions of ball players - it is unclear whether this was also worn during the game.

spectator

The often, but not always, inclines on both sides of the central playing area are reminiscent of spectator bleachers, but one must assume that they were only used to roll the ball back and were taboo for both players and spectators. Only the platforms on the surrounding walls, which were accessible via ladders, not stairs, and which were not very large, remained for the spectators, on which - depending on the size of the ball court - about 100 to a maximum of 500 (Chichén Itzá) people could be seated. From this one must draw the conclusion that the Mesoamerican ball game - at least in classical times - was not a popular spectacle, but primarily an elitist ritual and ceremonial event reserved for a small class of nobles. On a few small ceramics from the post-classical period, one can see that the walls of very few ball playgrounds on both long sides were extended to a few meters deep seating for spectators.

Others

As part of the art and culture program for the 2006 Soccer World Cup , Pok-ta-Pok games were performed in several German cities by the Mexican government in traditional clothing in recreated sports facilities based on the Mesoamerican ball game.

literature

- Gerard W. van Bussel: The ball from Xibalba. The Mesoamerican ball game . Art History Museum with Museum of Ethnology and Austrian Theater Museum, Vienna 2002.

- Michael D. Coe : The Secret of the Maya Script . Reinbek 1995, ISBN 3-499-60346-2 .

- Heidi Linden: The ball game in cult and mythology of the Mesoamerican peoples . Weidmann, Hildesheim 1993. ISBN 3-615-00076-5

- V. Scarborough, D. Wilcox: The Mesoamerican Ballgame . University of Arizona Press, 1993, ISBN 0-8165-1360-0 .

Web links

- Olmec sculpture from 800–400 BC. Chr., Which could represent a ball player.

- Antje Baumann: The ball game in pre-Columbian America

- Ruth Hardinger: Rubbings from the site of Dainzu Artistic interpretation of the depiction of ball players in the ruins of Dainzú

- Ballgame.org : Nice flash site (with distinction), which clearly prepares the topic for school lessons (English)

- [1] : Pre-Hispanic ball game in Mesoamerica (Spanish)

Individual evidence

- ↑ http://www.motecuhzoma.de/cort-karl.html

- ↑ Ballgame.org A very nice flash page (with distinction), which clearly prepares the topic for school lessons (English).

- ↑ Popol Vuh. The book of the council. Diederichs, Munich 1990, p. 78ff, ISBN 3-424-00578-9

- ↑ Diego Durán: Historia de las Indias de la Nueva España e islas de la Tierra Firme ed. by Angel María Garibay K. México, Porrúa 1967. pp. 205-210