Mesoamerican writings

On the American continent, writing systems were only developed in Mesoamerica in pre-Columbian times . This makes Mesoamerica one of the few regions in the world where the development of a script was not stimulated or influenced from outside. The Mesoamerican scriptures undoubtedly have common roots, without it always being possible to speak of a closer relationship.

The number of Mesoamerican scripts depends on the definition used: With the current state of knowledge, only the Maya script met the requirement that a spoken text can be reproduced simply by means of its graphic representation without the presence of the original speaker. Other graphic systems are able to record content independently of language, which is why it can also be reproduced in every conceivable language.

The spelling of calendar dates is one of the common features of many Mesoamerican scriptures. The characters for calendar periods or day names are usually written in a rectangular cartridge with or without rounded corners. The number signs consist either of points (discs) and bars or just of points.

Pre-Classical Fonts

It has not yet been decided which of the early writings from the area of the Olmec culture are to be considered the earliest. The reason for this is the difficult dating of stone monuments - the only witnesses to these early writings. The nature of the characters on the Cascajal stone is still controversial.

Olmec scriptures

see Olmec script

The oldest word signs ( logograms ) appear between 400 and 500 BC. BC, while earlier examples of cylinder seals with individual characters cannot yet be addressed as writing.

Monte Albán script

On Monte Albán there are numerous monuments that are assigned to the first two phases and that contain characters. Forerunners of this document have not yet become known. Similar characters have also been found in a larger room. The characters of phase I are arranged in vertical columns, a number of the characters are framed by rectangular cartridges with rounded corners. The numerals consist of undecorated bars (for the numerical value 5) and undecorated discs (for the numerical value 1), which were combined in such a way that the discs lay over the bar. A reading has not been attempted successfully for either the calendar or the other characters (in which logograms are suspected). The characters for the names of years are identified by distinguishing signs. It is not known what language was spoken by the builders of Monte Albán at the time.

The numerous stone slabs with graphical incisions on the outside of building J are assigned to phase II . Joyce Marcus suspects reports of conquests in these plates, the inscriptions of which are usually identical and which consist of a place symbol, a human head that “hangs down” underneath and one or more columns of symbols. In these character columns there are always at least two calendar characters, which together presumably indicate a date.

Isthmus script

The evidence for the isthmus or Epi-Olmec script can be found in a wide area north, east and northwest of the isthmus of Tehuantepec , but there are only a few finds with widely differing lengths of the texts. The Cerro de las Mesas site near Piedras Negras in Veracruz is a center with several columns of signs that are usually no longer clearly recognizable because of their weathering . Several of the monuments carry dates in a system that structurally corresponds to the Long Count of Mayan inscriptions and which, converted according to this system, date from the second to the sixth century. Attempts to decipher one of the longest inscriptions, the La Mojarra Stele 1, on the basis of a presumed belonging to a Mixe-Zoque , are still controversial.

Izapa script

Little evidence of the Izapa script has come to light, so it is uncertain whether it is a separate script. The longest text comes from Kaminaljuyú in Guatemala . A characteristic of some of the inscriptions is the use of the long calculation for the calendar record, which results in dates in the first century when the conversion established for the Mayan calendar is used.

Classical writings

Mayan script

see Mayan script

The script of the classical Maya culture is without a doubt the most powerful that was ever developed and used in the New World. As far as is currently known, it was the only one that was able to record a linguistically given text precisely, that is, aurally exactly reproducible. The script uses logograms and syllables in a variable combination , which makes it easier to confirm readings for deciphering. The Maya script makes intensive use of calendar information, not only in the Long Count, but also in other, mostly astronomical-based cycles.

Zapotec script

The writing of phases IIIA and IIB of Monte Albán differs significantly from that of the phases preceding it. The difference in the arrangement of the characters, which is no longer so precise, and in the execution is particularly noticeable. There are also changes in the character treasure, only a few characters seem to have been taken directly from the previous period. In contrast to before, there are no more numerical values above 13, from which it can be concluded that other calendar information was given.

Late Classical / Early Post Classical Fonts

Central Mexican writings

In the late classical period monuments with characters appeared in a number of places: in Xochicalco , Teotenango , Maltrata , as well as in Cacaxtla and occasionally in Tula . These are usually characters that are not related to the text, very often associated with numerals (bars and discs). There are also clearly designed characters that presumably express the names of places and people. Since the underlying language is not known, a reading is likely to be hopeless. Similar signs can also be found isolated, but embedded in scenes in bas-relief in Chichén Itzá , for example in the temple of Chac Mool.

ñuiñe font

In a small area around the town of Tequixtepec , mostly relatively small monuments from fortified hilltop settlements have been preserved. They show individual calendar signs (with circular cartouches) and presumably place symbols, which are reminiscent of the Mixtec symbols.

Cotzumalhuapa script

A number of monuments are known from the area of Cotzumalhuapa with simple representations of human figures (mostly in connection with the ritual Mesoamerican ball game ) in a field surrounded by a clearly raised frame. In this field peculiar calendar information is arranged at the edge: instead of a calendar symbol for a day and a separate number, the calendar symbols (in circular cartridges) are multiplied according to the intended number.

Late post-classical typefaces

In the post-classical period , a wide area from Central Mexico to the Caribbean coast spread across Mesoamerica, encompassing art and culture styles. This also included a form of written record in connection with a certain style of detailed narrative (narrative) visual representation. What this style had in common was a broad convention in the graphical realization of the themes to be reproduced.

Mixtec script

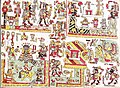

The evidence for the Mixtec script comes partly from stucco reliefs in archaeological sites. The largest part, however, can be found in the dozen or so illustrated manuscripts that have been preserved as originals from the Mixtec cultural area. The Mixtec pictorial writing combines the narrative representation, in which the content to be conveyed is reproduced by clear visual images, with characters for calendar dates, names of persons and places.

Mixtec manuscript Codex Nuttall , page 16

Aztec script

see Aztec script

The Aztec script is mainly known from a small number of stone monuments with a few characters for dates (years in a rectangular frame) and names of people and places. The convention of the representation is less strictly regulated than in the Mixtec script - however, this conclusion is perhaps inaccurate insofar as no illustrated manuscript from pre-Hispanic times has survived. The numerous copies and processing from the colonial period are each shaped to a different degree by the influence of European images during the colonial period, which obscures the view of the pre-Hispanic models.

literature

- Stephen D. Houston: Writing systems - overview and early development . In: The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican cultures . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-19-510815-9 . Vol. 3, pp. 338-340

- David Stuart: Writing systems - Maya systems . In: The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican cultures . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-19-510815-9 . Vol. 3, pp. 340-343

- Javier Urcid Serrano: Writing systems - Zapotec . In: The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican cultures . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-19-510815-9 . Vol. 3, pp. 343-344

- Maarten ERGN Jansen: Writing systems - Mixtec systems . In: The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican cultures . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-19-510815-9 . Vol. 3, pp. 344-346

- Hanns J. Prem : Writing systems - Central Mexican systems . In: The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican cultures . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2001. ISBN 0-19-510815-9 . Vol. 3, pp. 346-347

- Hanns J. Prem: Calendrics and writing . In: Contributions of the University of California Archaeological Research Facility, No. 11, 1971. pp. 112-132.

Individual evidence

- ^ Joyce Marcus: The iconography of militarism at Monte Albán and neighboring sites in the Valley of Oaxaca . In: Henry B. Nicholson (Ed.): Origins of religious art and iconography in preclassic Mesoamerica . UCLA Latin American Studies Series, Los Angeles 1976, ISBN 0-87903-031-3 . Pp. 125-139