cubism

Cubism is a style in art history . It emerged from a movement of the avant-garde in painting from 1906 in France. Its main founders are Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque . Other representatives are Juan Gris and the Puteaux group , in particular Fernand Léger , Marcel Duchamp and Robert Delaunay , to whom Orphism goes back.

Analytical and synthetic cubism emerged from what is known as early cubism. Cubism replaced Fauvism in France . Cubism did not have its own theory or manifesto . Cubism introduced Classical Modernism with Fauvism . At the beginning of World War I in 1914, the movement began to disintegrate.

From today's perspective, cubism represents the most revolutionary innovation in the art of the 20th century. Cubism created a new order of thought in painting. The bibliography on Cubism is more extensive than any other style in modern art . The influence of cubist works on the subsequent styles was very great.

Cubism also spread to sculpture , and this is how cubist sculpture came about . The artists found further fields of activity in architecture and music as well as in film .

Concept and point of view

The word cubism is derived from the French cube or Latin cubus for cube . Charles Morice used the term in an April 16, 1909 article in the Mercure de France about Braque's pictures from the Salon des Indépendants . Louis Vauxcelles then established the term cubisme in his report on Braque's work in the Salon of 1909. From then on, the most recent paintings by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braques were assigned to the newly created style . According to Guillaume Apollinaire , Henri Matisse was the first to speak of “petits cubes” when looking at a landscape painting by Braque in the autumn of 1908 .

The gallery owner and art historian Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler wrote in his book Der Weg zum Kubismus , published in 1920, that one should not take the name as a program, because otherwise one would “reach wrong conclusions”. The name and the designation as geometric style , which was widespread in France at the beginning of the movement , arose from the impression of the first viewer who saw geometric shapes in the paintings. The vision desired by Picasso and Braque, however, does not consist in geometric shapes, but in the representation of the objects reproduced and the structure of the painting.

However, the early images and the term itself gave the impression that Cubism was oriented towards the geometrical abstraction of form. This view was supported by the work of the Puteaux group . The audience was presented with this more catchy idea in the 1912 publication Du cubisme .

characterization

Regardless of where the origin of Cubism is found, Pablo Picasso laid the foundation for Cubist thinking with his large-format painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1906–1907). The Demoiselles d'Avignon changed the nature and concept of painting itself. Before that, the aim was to create an illusion that showed the objects spatially and plastically. This representation has now changed.

Cubism broke away from the foundations of previous painting. It can be read in two ways:

- as a final break. The cubist image no longer wants to represent the (apparent) world. Instead, it is primarily about structuring the space of a painting formally and harmonizing the resulting distributions of values and forces.

- or it is seen as a conceptual break with the rules that have prevailed since the Renaissance : the elimination of traditional chiaroscuro , perspective and the skillful, handcrafted brushstroke.

The development of Cubism is described in the art historical reviews as the greatest adventure of the 20th century. As a result of the dynamic development and concatenation of insights and discoveries that emerged in Cubism, a visual dialectic gradually emerged for the art of the 20th century. The important legacy for the following generations lies in the implementation of the definition of Leonardo's painting as cosa mental - a matter of the spirit - in the 20th century.

Art historical introduction

painting

Since the Renaissance (approx. 16th / 17th century) the purpose and task of painting was to convey something pictorially. Painting should imitate nature and illustrate its appearances . In the middle of the 18th century, however, the tasks of painting began to be rethought and pure depiction came to the fore. Then around 1800 there was also doubt that painting could depict the (apparent) world, because it only succeeded in doing this with illusions, with mechanisms that are basically purely technical and also unreliable. The means of painting, drawing and color were released from their previous tasks and recognized as something independent. The aesthetic effect of the picture was now the primary concern.

Previously, content and form, message and appearance had to match, now the form was important. Form became content. The philosophy of the time taught that intuition, concept and knowledge belong together. Building on this, painting as a pure form of intuition should acquire its spiritual content. Both the French art of the 19th century and the Nordic art that has not run parallel to it since the German Romanticism pushed for an ever greater independence of the image.

Art trade

In the 19th century it was almost exclusively the official salons that decided on the recognition of artists. In the further course, from around 1884 onwards, discussions about salon and anti-salon art sparked . From around 1900 it was mainly the art trade in association with a more or less independent journalism that steered the development. Most of the important overviews of avant-garde art took place in the galleries. They also acted as intermediaries between the studios and the public. Certain artists were built up and marketed exclusively: an early indication of a commercialization of art that was emerging with bourgeois society .

Birth and Origin of Cubism (1906–1908)

Picasso's studies from 1906 and Cézanne retrospective (1907)

The cubist development began in Picasso's work in 1906. It found its first expression in works such as a portrait of a woman with clasped hands . This period of Picasso is called the protocubist phase .

He dealt not only with the works of Paolo Uccello , Piero della Francesca , El Greco , Nicolas Poussin , Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Paul Cézanne , but also with "primitive" art . At the end of this journey, there was a breakthrough in the reformulation of painting. His advances made during these years came to a preliminary conclusion in the summer of 1907 with the famous painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon . Josep Palau i Fabre sees a kind of superfauvism in the work , so the Demoiselles were also motivated by the painting Le bonheur de vivre (1905/06) by Henri Matisse . With the Les Demoiselles d'Avignon , the young Spaniard initiated the discussion about modernity alongside Matisse and Derain .

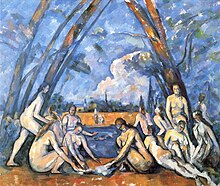

The extensive retrospective of Paul Cézanne's work in the autumn salon in 1907 occupied the young painters of the time, especially Picasso, Braque and Derain. Cézanne's freer handling of the natural model, form and color perspective and its formal and analytical approach became the point of reference for the upheaval of 1907. About Cézanne's influence in this period, Braque later said: “It was more than an influence, it was an initiation. Cézanne was the first to turn away from the learned mechanical perspective . "

Kahnweiler, the gallery owner of Picasso and Braques, noted that Derain had grasped Cézanne's teaching and conveyed his new thoughts to them. There is a direct line from Cézanne's bathers to Matisse ' Nu bleu: souvenir de Biskra ( Blue Nude (memory of Biskra) ) and Derains Baigneuses (bathers) to finally Les Demoiselles d'Avignon .

Picasso, Braque and Derain (1906–1908)

According to reports by the writer Guillaume Apollinaire , Cubism emerged from Picasso's encounter and confrontation with Derain in 1906. The art-historical review relates the birth of Cubism to the six-year dialogue (1908–1914) Picasso and Georges Braques , who previously painted in Fauvist style .

At the end of 1907, Braque saw the Demoiselles d'Avignon in Picasso's studio in the Bateau-Lavoir . His first reaction was negative: "With your pictures you apparently want to make us feel like swallowing ropes and drinking kerosene." Henri Matisse and André Derain were also negative. From now on, Picasso's studio discussed his other works and the Braques from the fishing village L'Estaque , which were created in the summer of 1907.

While Picasso rarely showed his work in public, Braque and Derain presented their new works in March 1908 at the Salon des Indépendants. The writer and art collector Gertrude Stein reported: “We […] saw […] two large pictures that looked pretty similar. One is from Braque, the other from Derain, [...] The pictures seemed strange to us, with oddly shaped figures like blocks of wood. "

If Picasso suspected Braque in the spring of wanting to exploit his work without identifying the connection with the author, in autumn 1908 they compared the works they had created in the summer. The images were strangely similar, like Picasso's Maisonette dans un jardin and Houses in L'Estaque by Braque.

Braque's pictures, which were rejected in the Autumn Salon (Salon d'Automne) in 1908, were shown in the Kahnweiler Gallery. The exhibition opened on November 9, 1908, the day after the autumn salon closed. It caused a stir in artistic circles. In his review in Gil Blas of November 14, 1908, Louis Vauxcelles was the first to associate the works with the term "cubes": "He despises shapes, reduces everything [...] to basic geometric shapes, to cubes." he used this style as “cubist” and by the end of 1909 this expression was used by all painters and critics.

At the end of 1908, Braque and Picasso began a lively dialogue, often with Derain's participation. Braque later recalled: “It did not take long and I exchanged ideas with Picasso every day; we discussed and examined each other's ideas […] and compared our respective works. ”The joint creative period of the two artists that was now beginning became famous with the expression “ la cordée ” (the rope team). Their collaboration was so close and cooperative that they compared themselves to the Wright brothers , the flight pioneers, and dressed like mechanics. Derain moved away from the aspirations of Cubism in 1911.

Early Cubism around 1908 - Picasso and Braque

“They tried to explain cubism mathematically, geometrically, psychoanalytically. This is pure literature. Cubism has plastic goals. We see in it only a means of expressing what we perceive with the eye and the mind, using all the possibilities that lie in the essential properties of drawing and color. That became a source of unexpected joys, a source of discovery. "

The starting point of Cubism was to eliminate the “ancient” conflict of a painting: the illustration of the form - the representation of the three-dimensional and its position in space - on the two-dimensional surface while preserving the unity of the work. A lyricism of forms developed or, to put it in Picasso's words: “Cubism has never been anything other than this: painting for the sake of painting, excluding all concepts of non-essential reality. Color plays a role in the sense that it helps to represent the volume. ”Braque and Picasso thus abandoned the path of preserving the greatest possible natural probability - the“ real ”form and the“ real ”color - of what is being represented.

| The dryad |

|---|

| Pablo Picasso , spring – autumn 1908 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 185 × 108 cm |

| Hermitage, St. Petersburg

Link to the picture |

Braque's first works provide a decisive structural model for the false relief of early Cubism. With the scale-setting picture Violin and Jug , completed in early 1910, the quality of his work fully corresponds to his ingenuity. A work by Picasso from the early Cubist phase is Die Dryade (Nude in the Forest) from spring-autumn 1908.

Braque joined after the XXV. Exhibition of the Salon des Indépendants in 1909 of Picasso's decision to no longer exhibit in the Salon. The works of Picasso, which had rarely been seen in public before, and Braques were only present in the gallery exhibitions at Kahnweiler and Ambroise Vollard . Between 1908 and 1913, Picasso and Braque either did not sign their pictures at all or afterwards on the back. They were guided by the desire to eliminate the character of the personal.

Analytical Cubism (1909–1912) - Picasso and Braque

"Deform the senses, but the mind forms."

The term analytical cubism goes back to the writing The way to cubism by Kahnweiler from the year 1920. In analytical cubism, the closed form of the depicted body was broken up in favor of the rhythm of forms. The physicality of things and their position in space could be represented in this way without faking them through illusionistic means.

| The pond of Horta |

|---|

| Pablo Picasso , 1909 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 60 × 50 cm |

| Private collection, New York

Link to the picture |

In the main phase of cubism that was now beginning, there was a change in painting. Since the Renaissance , people had sought to paint light as color on the surface of the body in order to simulate the shape on the picture surface. The color - as light that had become visible - was responsible as chiaroscuro to shape the shape. It could not be applied as a local color at the same time , nor could it even be used as a “color”, but rather as objectified light. The direction of light now played a subordinate role in the works of the analytical cubism of Picasso and Braque. In the paintings it was not specified which side the light comes from.

The necessary “deformation” of the bodies in the picture also disturbed the two painters in their early works, for example in Picasso's The Dryad . It was tormenting to many onlookers. The conflict arose in them between the deformation of the “real object” as a result of the “rhythm of forms”, in contrast to the memory images of the same object. This, however, was inevitable as long as even a distant “natural similarity” of the work of art triggered this conflict.

| Violin and pitcher |

|---|

| Georges Braque , 1910 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 117 × 73 cm |

| Art Museum, Basel

Link to the picture |

Picasso and Braque no longer proceeded from an assumed foreground, but from a fixed and represented background. Starting from this background, they now painted forward, in which the position of each body was clearly represented by its relationship to the fixed background and the other bodies. In this way, the traditional division of an image into foreground, middle and background has been eliminated.

The method of representation makes it possible to view the objects in the picture simultaneously (simultaneously) from different angles (polyvalent perspective). The concept of simultaneity has thus grown into a motto of Cubism in the art historical review. Often some parts of the image appear transparent, which means that several levels are visible simultaneously. This creates the effect of a “crystalline” structure.

The two artists expanded the level of the use of signs in the picture, processed symbols and set content-free color structures on the other hand. This mechanism was taken to the limit of pure abstraction in 1910, as in The Guitar Player or The Clarinet . They made the process of creating and designing images the subject of their pictures.

Puteaux group from 1910

"It took me three years to get rid of Cézanne's influence [...] The bias was so strong that I had to go to abstraction to get rid of it."

When confronted with the cubist images, some artists felt aesthetically touched. Very soon they came up with theories of what Cubism was and what it should be.

They include the painters Fernand Léger , Robert Delaunay , Marcel Duchamp , Jacques Villon , Francis Picabia , Roger de La Fresnaye , Henri Le Fauconnier , Albert Gleizes , Jean Metzinger , for a while Raoul Dufy and Othon Friesz , André Lhote , Moise Kisling , Auguste Herbin , Léopold Survage , Louis Marcoussis , Diego Rivera , Piet Mondrian and the sculptors Alexander Archipenko , Constantin Brâncuși , Jacques Lipchitz and Raymond Duchamp-Villon . Several of these artists merged with Apollinaire in 1910 to form the Groupe de Puteaux , in which the American Walter Pach also moved. Your meeting point was the house of Jacques Villon in Puteaux . They called themselves Cubists and had their public breakthrough in the spring of 1911 in the Salon des Indépendants . The exhibited images are based on the geometrical abstraction of the form, as suggested by the conceptualization derived from the cube. Almost all paintings can be understood as "pleasing" variants of Picasso's and Braque's early phase around 1908.

Jacques Villon described himself as an impressionist cubist. Works from 1911 are The Tea Hour by Jean Metzinger, The Lake by Henri Le Fauconnier and The Chartres Cathedral by Albert Gleizes from 1912.

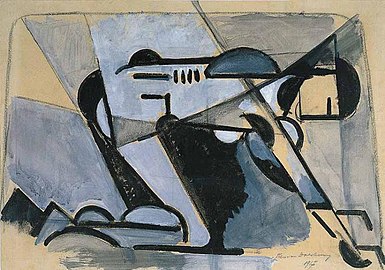

An exception was the picture Nus dans la forêt (Nus dans la forêt) exhibited by Fernand Léger . It prompted the art critic Louis Vauxcelles to no longer speak of Cubism in connection with Léger's art, but of Tubism (tube art) . Léger's later use of color is seen as an isolated phenomenon within Cubism, for example Der Rauch from 1912. It occupies a separate position and expanded the pictorial themes of Cubism with a new and topical subject: the relationship between man, machine and technology .

Robert Delaunay began a series of images on the Eiffel Tower from 1909 to 1912. The picture Looking through the Eiffel Tower from 1910 shows the Eiffel Tower seen through a window. When pure color became an essential part of his paintings, Apollinaire christened this style Orphism in 1912 .

Marcel Duchamp integrated the movement into the cubist image. In 1912 he submitted his painting Nu descendant un escalier no. 2 (Nude, descending a flight of stairs no. 2) to the Salon des Indépendants, where it was rejected by the other members of the group. In the history of art it is counted among the key works of painting of the 20th century, as it contains the aspirations of futurism , the representation of movement in the picture .

From the point of view of art theory, the works of the late Cubists are associated with an increasing humanization of Cubism. In the course of time, many artists in the Puteaux group completely gave up the object and with it any relation to reality. Her pictures became completely abstract. In contrast to the Groupe de Puteaux , Picasso and Braque rejected the path to pure abstraction. From their point of view, one misunderstood and falsified the structure of a work of art, which they call Cézanne's greatest merit, if one believes that one has arrived at it by simply dividing the surface of a painting into pleasant proportions. Such a tendency only paves the way to the deepest degradation of painting to pure ornamentation, to ornamentation .

The Puteaux group appeared from 1912 under the name Section d'Or , an exhibition community to which Juan Gris also belonged.

Synthetic Cubism (1912–1914) - Picasso, Braque and Gris

"If what was called cubism was only a certain aspect, then cubism has disappeared, if it is an aesthetic, then it has united with painting."

Synthetic Cubism is essentially based on the collage technique practiced by Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and later also by Juan Gris , the paper collé . For the papier collés , which can be seen as the basis of all subsequent collage techniques up to the ready-made , Braque and Picasso were inspired by their previously created three-dimensional constructions, the paper sculptures, which they made from paper and cardboard, Picasso later from sheet metal , made.

With Braque's picture Compotier, bouteille et verre (fruit bowl, bottle and glass) (1912), the first paper collé was created . From then on, paper, newspaper, wallpaper, imitation wood grain, sawdust, sand and similar materials appeared in her pictures. The boundaries between the painted and real object and the object flow into one another. The images processed in this way acquire a tangible, material character that creates a new reality for the image.

Alongside Picasso and Braque, Juan Gris is considered to be the main representative of synthetic cubism. Gris had lived in Bateau-Lavoir since 1908 and met Picasso there. They were studio neighbors. In 1911, Gris began to grapple with Cubism. His first works such as Maisons à Paris (Houses in Paris) are created .

Gris was a theorist and incorporated the new design principles into a rational system. Throughout his career he tried to convey his artistic approach theoretically. Picasso, in turn, completely rejected a theoretical approach to Cubism. Neither Picasso nor Braque had the intention of starting a school. They were concerned with an intelligence whose realm is neither the domain of science nor of the verbal, but only of the pictorial.

End of cubism after 1914

With the outbreak of the First World War , the situation changed suddenly for the artists. Many of them were called up for military service. The Puteaux group disbanded after 1914. The exchange of information between the artists almost completely came to a standstill. Cubism as a movement went down in the turmoil of the First World War. However, its survival as a style has not diminished in art production up to our days.

On August 2, 1914, Picasso accompanied Braque and Derain, who had received their position orders, to the train station in Avignon. Braque suffered a serious head injury in 1915 and after surviving an operation, it took more than a year to recover. The war broke the deep friendship between Picasso and Braque, whose personality had changed as a result of the serious head injuries.

Picasso remembered his departure from Cubism: “One wanted to make a kind of physical culture out of Cubism. [...] From this an artificial art has emerged, without any real relation to the logical work that I try to do. "

Publications on Cubism from 1912

First public discussion (1911)

The Puteaux Group's official exhibitions from 1911 onwards led to a public discussion of Cubism, which made the works of Picasso and Braque widely known. Since the Salon des Indépendants of 1911, the cubists have been divided into two groups. The so-called Salonkubisten were the Galeriekubisten against Braque and Picasso. An exception was Fernand Léger, whose works were shown in the Kahnweiler Gallery from 1912. The Salon Cubists were denied access to the studios of Braque and Picasso . A series of press reports even led to heated discussions in political bodies. The second exhibition of the Puteaux Cubists in the Salon des Indépendants in 1912, the group of which had grown in the meantime, led to a scandal that can only be compared with the fuss about the appearance of the Fauves in 1905.

The controversy was already evident when the artists of the Puteaux group called themselves Cubists in 1910-11. In a review of the Picasso exhibition at Galerie Vollard from December 20, 1910 to February 1911 by André Salmon , the Paris Journal read: “Picasso has no followers, and we have to endure the audacity of those who make public statements in manifestos to be his followers and to mislead other frivolous souls. "

First publications from 1912

In collaboration with Gleizes, who was active as a painter, illustrator and art writer, Metzinger wrote the theoretical treatise Du cubisme (On Cubism) , which was published in 1912 by Figuière in Paris. In this collection of easily understandable formulas based on the Cézanne model, the statements refer to an analytical approach to creating an image that was not conducive to understanding Cubism. Her pictures clearly show that the cubist artists had found very different means. Regardless of all criticism of the publication, the publication played a special role as a social multiplier due to the few exhibitions.

The numerous publications from the Puteaux group were opposed by just as many of the writers of the Picasso group. In 1912 André Salmon published two books that are still considered to be sources on the art of classical modernism: the anecdotal history of cubism (Histoire anecdotique du cubisme) and a treatise on new painting in France (La jeune peinture française) . Salmon was the first to draw attention to the key role Picasso and his painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon played in the founding of Cubism.

In March 1913 published Apollinaire with Les peintres cubistes: Médiations esthétiques a collection of essays on Cubism and the Cubists. Attempts have already been made in this publication to classify and characterize the different groups in this direction. Braque and Picasso are seen as "scientific cubists". Picasso let his gallery owner and confidante Kahnweiler know: “Your news about the discussions about painting is really sad. I received Apollinaire's book on Cubism. I'm really depressed by all of this chatter. "

In 1928 another Gleize publication on Cubism appeared in the series of Bauhaus books . In this pamphlet, the author again emphasizes the conflict with the authors: "Braque and Picasso only exhibited in the Kahnweiler Gallery, where we ignored them." Gleizes further describes that the term Cubism was not yet in circulation in 1910 and only became public when the works of the Puteaux group were presented in the Salon des Indépendants in March 1911.

The way to cubism (1920) - Kahnweiler, the gallery owner

As a scientific author and exhibition curator, the gallery owner Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler was largely responsible for the spread of Cubism as an art style. He was one of the first to view the Demoiselles d'Avignon and signed his first exclusive contracts with Derain, Braque and Vlaminck in 1907 . He signed Picasso for the first time in 1911, Juan Gris the following year and Fernand Léger in 1913.

In his publication Der Weg zum Kubismus , published by Delphin Verlag, Munich, in 1920 , Kahnweiler describes the thoughts and the chronological course of Cubism from the point of view of the gallery cubists . The main parts of the text were written between 1914 and 1915, first published in 1916 in Die Weißen Blätter in Zurich, and due to the war it appeared in 1920.

The script is divided into five main parts: The essence of the new painting. The lyricism of forms. The conflict between representation and structure - The forerunners: Cézanne and Derain - Cubism. First stage: the problem of form. Picasso and Braque - Cubism. Second stage: breaking through the closed form. The problem of color. Viewing categories. Picasso and Braque in Joint Work - The Classical Perfection of Cubism. Juan Gris.

After the end of the war, Kahnweiler added another section to the publication: The image as an effective end in itself. Léger .

Exhibitions of cubist works

In the period between 1908 and 1914 there were only a few gallery presentations at Kahnweiler or Vollard. The Salon Cubists showed their works in the salons in spring and autumn. Since 1910, the gallery owner Kahnweiler has been sending works by the artists he represents to avant-garde exhibitions abroad, for example to the Sonderbund exhibitions that alternate between Düsseldorf and Cologne . Pictures by Braque and Picasso were shown in these in 1910, 1911 and 1912.

In September 1910, the Thannhauser Gallery showed works by Braque and Picasso in Munich. The 1910 exhibition of the Jack of Diamonds in Moscow showed works by the salon cubists Gleizes, Le Fauconnier and Lhote. In 1911 only works by Gleizes were exhibited, in 1912 by Gleizes, Léger, Picasso and Le Fauconnier, and in 1913 by Picasso and Braque. Delaunay participated in the first exhibition of the Blue Rider in Munich in 1911 with four paintings .

From October to November 1912, the Modern Art Kring exhibition in Amsterdam presented works by Braque, Gleizes, Léger, Metzinger and Picasso. The Gallery 291 of Alfred Stieglitz in New York showed March-April 1911 drawings and watercolors by Picasso. Stieglitz previously visited the studios of Matisse , Rodin and Picasso in Paris and remembered a "tremendous experience".

From February 17 to March 15, 1913 , works by Picasso, Braque, Picabia, Léger, Gleizes, Duchamp-Villon, Villon were presented at the first Armory Show , the international exhibition of modern art in the former armory of the 69th Cavalry Regiment in New York , Duchamp, Delaunay and de La Fresnaye. Further exhibition stops were then Chicago and Boston.

In 1913 the first Picasso retrospective took place in Heinrich Thannhauser's Munich gallery in Germany. It was then shown in Prague and Berlin. From December 1914 to January 1915, Stieglitz presented 20 works by Braque and Picasso in New York. The works came from the collection of Gabrielle and Francis Picabia .

First reactions and testimonials

On March 20, 1908, Louis Vauxcelles wrote in Gil Blas about Braque's works shown in the Salon des Indépendants: “In Braque's presence I lose all orientation. This is a wild, determined, aggressively obscure art. "

In the edition of La Liberté of March 24, 1908, Etienne Charles wrote in the second part of a two-episode review of the work of Braques and Derain by the Salon des Indépendants: “One senses a strong preference for deformed, overdrawn and ugly women. With the representatives of the new direction, gallantry is not in fashion. "

On April 16, 1909, Charles Morice wrote in an article in the Mercure de France , in which the term Cubism appeared in writing for the first time, about the works of Braque, which were published in the XXV. Exhibition of the Salon des Indépendants were: "And I believe that Mr Braque - with the exception of Cubism - is a victim of his admiration for Cézanne, which is too exclusive or one-sided."

Henri Guilbeaux wrote in Hommes du Jour on January 7, 1911 : “It is said that Picasso is ready to give up the wrong path that he has been following for some time. That would be better because this painter is very talented. So only the cubists and sub-cubists remained, whom Charles Morice could gather to form a cohort [...] "

Michael Puy wrote in 1911 in the magazine Les Marges : “Cubism is the culmination of simplification, begun by Cézanne and continued by Matisse and Derain […] It is said that it began with Mr Picasso, but since this painter did his work seldom exhibits, the cubist development was mainly observed in Mr. Braque. "

After the exhibition of 83 drawings and watercolors by Picasso in New York in 1911, organized by Alfred Stieglitz in his gallery 291 , the May 1, 1911 issue of The Craftsman read: “But if Picasso seriously expresses his feeling for nature in his studies, then must you think he is a raging lunatic, because something more disconnected, less unrelated and less beautiful than this representation of his own feelings is difficult to imagine. "

Alexander Archipenko summarized in an article in the International Review of Contemporary Art in 1922 :

“You can say that Cubism created a new order of thought in relation to the image. The viewer no longer delights, the viewer is creative himself, ponders and creates an image by relying on the plastic features of those objects that are sketched as forms. "

Cubist sculpture

Cubist sculpture developed at a later date than cubism in painting . For example, some authors consider the sculpture Head of a Woman (1909) by Picasso to be the first sculpture in the Cubist style. However, it was not until the 1920s that cubist sculpture reached its heyday.

Aristide Maillol , who broke away from Rodin's painterly concepts and led the sculpture to rhythmically abstracted volumes, is considered a forerunner of cubist sculpture. The actual Cubist sculpture was carried by Picasso's reliefs and the three-dimensional work of the Russian Alexander Archipenko . Other early representatives are the German Rudolf Belling , Constantin Brâncuși and Raymond Duchamp-Villon .

The French sculptor Henri Laurens met Braque in 1911 and began creating his paintings, collages and sculptures in the Cubist style. Another important representative is Jacques Lipchitz , whose sculptural work is influenced by Cubism.

The faceted, multi-layered design inspired the Italian futurist Umberto Boccioni , who had seen the new sculptures by the Cubists in 1912 while visiting his studio in Paris. Boccioni expanded the design principle of the cubist "multi-perspective" by the factor of dynamics.

Effects of Cubism

Influence on European and non-European painting

Despite the relatively low public acceptance of the Cubists, many artists showed great interest in their work. The many studio visits by foreign artists are evidence of this. For example, Umberto Boccioni and Carlo Carrà visited Picasso in his studio. After meeting Picasso, Boccioni was always keen to hear all the news. Also examined Vladimir Tatlin Picasso's studio, and very probably the Braque. In 1912 Paul Klee , Franz Marc , August Macke and Hans Arp visited Delaunay in Paris. Delaunay and Apollinaire again met Macke in Bonn. Le Fauconnier was a member of the Neue Künstlervereinigung München between 1909 and 1911 , when the latter organized three important exhibitions at the Munich gallery Thannhauser .

The works of the artists who shaped Cubism - above all Picasso and Braque - revolutionized contemporary art and especially painting between 1907 and 1914. In January 1913, Apollinaire gave a lecture on the occasion of an exhibition by Robert Delaunay in the gallery Der Sturm in Berlin, which was later published under the title Modern Painting in the magazine Der Sturm . This is one of the earliest references to the new paper collé and collage process.

In retrospect, Cubism had a profound influence on the later artistic movements of the 20th century, specifically on Italian Futurism , Russian Cubofuturism , Rayonism and Suprematism , French Orphism and Purism , the Blue Rider in Germany, the De Stijl movement in the Netherlands and finally the internationally widespread Dadaism , as well as all constructive art, such as constructivism . In the United States , as a result of the Armory Show, Cubism was briefly gleaned by regional artists who found a “Cubo-realistic” imagery in so-called Precisionism . All leading artists of the first half of the 20th century were influenced by Cubism in their early creative phase, and some were clearly shaped by its inventions, such as papier collé, and pictorial forms.

Futurism

Umberto Boccioni :

La strada entra nella casa , oil on canvas (1911)Cubofuturism

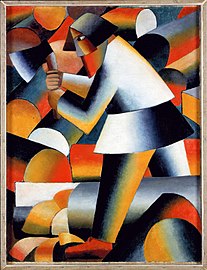

Kasimir Malewitsch

The Woodcutter , oil on canvas (1912/13)Der Blaue Reiter

Franz Marc :

Foxes , oil on canvas (1913)Paul Klee :

Motif from Hammamet , watercolor (1914)De Stijl

Theo van Doesburg :

Kneeling Nude , gouache on paper (1917)

Orphism - Orphic Cubism

The works created by Robert Delaunay around 1912 led Apollinaire to coin the term Orphism. Orphism describes an art movement that emerged from Cubism, in which circular shapes in bright colors were created on the basis of the color theory of the chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul . Apollinaire saw in Orphism an overcoming of Cubism. The works created by Delaunay and Léger around 1911 make special use of the design principles of color, light and dynamics. Rayonism in Russia followed similar approaches . Orphism has also found a name through Orphic Cubism, but like Cubofuturism is assigned to the effects of Cubism.

purism

Following Cubism is an oriented to the architecture style, the 1918 with the manifesto developed from 1917 Après le cubisme (After Cubism) by the artists Amédée Ozenfant and Charles-Edouard Jeanneret (Le Corbusier) as purism was proclaimed. As early as 1915, in the self-published magazine L'Elan, Ozenfant had already presented initial ideas about a pure, “pure” art form that should be simple, functional and without decorative elements. In doing so, the purists provided an ideological approach that continued the distance from representationalism and was implemented in Suprematism , Constructivism and the Bauhaus and had an influence on minimalist art and architecture in the second half of the 20th century .

architecture

Cubism is also important because of its influence on design and architecture . Cubist architecture can be found above all in Prague , the main artists to be mentioned are Josef Chochol, Josef Gočár and Pavel Janák .

A special development of Czech Cubism in Prague and Königgrätz was represented by Rondo Cubism , which manifested itself in the architecture of Gočár and Janák, but also in the paintings of Josef Čapek and in object design.

House of the Black Mother of God in Prague

Rondo cubist kiosk at the main train station in Prague (Pavel Janák)

Villa Bauer in Libodritz

Photography and film

Photography and the film avant-garde of the 1920s were also heavily influenced by Cubist painting. Fernand Léger made a “mechanical ballet” in 1924, a film in which a woman climbs a flight of stairs without arriving. Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp made abstract films with a geometric design language. The photographs of the 1920s by Alfred Stieglitz , who originally studied mechanical engineering, were also influenced by Cubism and Precisionism .

music

Although the transfer of terms from the visual arts to other arts and especially to music is problematic and has been widely criticized, two contemporary compositions in particular are also considered Cubist works: the two ballets Le sacre du printemps by Igor Stravinsky (1911/13) and Parade by Erik Satie (1917). The latter had been furnished by Picasso with sets and costumes in a cubist style. Apart from the intellectual closeness of the composers to the ideas of Cubism, the breaking up of conventional methods of composition and the assembly of a work of art by stringing together bulky, largely unchanged, and often heterogeneous individual elements, speak in favor of this.

Cubism artist

Artists who are assigned to or were closely related to Cubism, see category: Artists of Cubism .

literature

- David Cottington: Cubism . Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern-Ruit 2002, ISBN 3-7757-1151-1

- Pierre Daix , Joan Rosselet: Picasso - The Cubist Years 1907-1916 , Thames and Hudson Ltd., London 1979, from the French. Le Cubisme de Picasso, Catalog raisonné de l'œuvre translated by Dorothy S. Blair, ISBN 0-500-09134-X

- Hajo Düchting: How do I know? The art of cubism . Belser, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-7630-2477-3

- Josep Palau i Fabre : Picasso - Cubism . (Translated from Catalan by Wolfgang J. Wegscheider), Könemann Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, Cologne 1998, ISBN 3-8290-1450-3

- Anne Gantführer-Trier, Uta Grosenick (eds.): Kubismus , Benedikt Taschen Verlag GmbH, Taschen 25th anniversary special edition, 2nd edition 2007, ISBN 978-3-8228-2955-4

- Albert Gleizes / Jean Metzinger : You cubisme, on cubism, about cubism . RG Fischer, Frankfurt / M. 1993, ISBN 3-89406-728-4 (original edition 1912)

- Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler : The Way to Cubism , Delphin, Munich 1920 ( (excerpt online) )

- William Rubin : Picasso and Braque. The birth of cubism . (Original edition: Picasso and Braque, Pioneering Cubism , Museum of Modern Art, New York, September 24, 1989 - January 16, 1990, translated from English by Magda Moses and Bram Opstelten), Prestel Verlag Munich, Munich 1990, ISBN 3- 7913-1046-1

- Carsten-Peter Warncke, Ingo F. Walther (Eds.): Pablo Picasso , 2 volumes, Benedikt Taschen Verlag GmbH, Cologne 1991, ISBN 3-8228-0425-8

- Bernard Zurcher: Georges Braque - Life and Work (translated from the French by Guido Meister), Hirmer Verlag, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-7774-4740-4

Web links

- Search for Cubism in the German Digital Library

- Search for cubism in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- Cubism (1907 - around 1925)

Illustrations

- ↑ Pablo Picasso: Maisonette dans un jardin , August 1908, oil on canvas, 92 cm × 73 cm, State Pushkin Museum, Moscow

- ^ Jean Metzinger: The Tea Hour , 1911, oil on canvas, 75.9 cm × 70.2 cm, The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia

- ^ Henri Le Fauconnier: Der See , 1911, oil on canvas, Hermitage, Saint Petersburg

- ↑ Albert Gleizes: The Cathedral of Chartres , 1912, oil on canvas, 73.6 cm × 60.3 cm, Sprengel Museum, Hanover

- ↑ Fernand Léger: Nus dans la forêt , 1910, oil on canvas, 120 cm × 170 cm, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

- ↑ Fernand Léger: Der Rauch , 1912, oil on canvas, 92 cm × 73 cm, The Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo

- ^ Georges Braque: Compotier, bouteille et verre , 1912, oil on canvas

- ↑ Juan Gris: Maisons à Paris , 1911, oil on canvas, 52.4 cm × 34.2 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e Anne Gantführer-Trier: Kubismus , 2007 pp. 19–22

- ↑ Judith Cousins: Comparative Biographical Chronology Picasso and Braque . From William Rubin: Picasso and Braque. The Birth of Cubism , 1990, p. 350.

- ^ A b Anne Gantführer-Trier: Kubismus , 2007, pp. 6-8

- ^ Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler: The way to cubism . Verlag Gerd Hatje Stuttgart, first edition 1920, p. 20

- ^ Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler: The way to cubism . Verlag Gerd Hatje Stuttgart, first edition 1920, p. 62

- ↑ a b c Carsten-Peter Warncke, Ingo F. Walther (Ed.): Pablo Picasso , Taschen Verlag, Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-8228-3811-2 , Volume 1, p. 203

- ↑ a b c d e f g Patrick O'Brian: Pablo Picasso. A biography . Ullstein, Frankfurt / M / Berlin / Vienna 1982, pp. 235-237

- ^ Josep Palau i Fabre: Picasso. Cubism , 1998, pp. 24-26

- ↑ a b c d e William Rubin: Picasso and Braque. The Birth of Cubism , 1990, pp. 9-11

- ^ A b Carsten-Peter Warncke: Pablo Picasso , 1991, vol. 1, pp. 165–167

- ↑ Carsten-Peter Warncke, Ingo F. Walther (Ed.): Pablo Picasso , Taschen Verlag, Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-8228-3811-2 , Volume 1, p. 204

- ↑ a b c Josep Palau i Fabre: Picasso. Cubism , 1998, p. 39

- ^ Alfred H. Barr Jr .: Picasso. Fifty Years of his Art , The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1946, p. 61

- ↑ a b c Carsten-Peter Warncke: Pablo Picasso , 1991, Volume 1, pp. 143-145

- ↑ a b c Patrick O'Brian: Pablo Picasso. A biography . Ullstein, Frankfurt / M / Berlin / Vienna 1982, pp. 216-217

- ↑ Jane Fluegel, William Rubin (Ed.): Pablo Picasso. Retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, New York , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1980, pp. 86–87

- ^ Klaus Herding : Pablo Picasso: Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. The challenge of the avant-garde. , Frankfurt a. M. 1992, pp. 23-28

- ↑ Siegfried Gohr: I don't look, I find. Pablo Picasso, Life and Work , DuMont Verlag, Cologne 2006, p. 19

- ^ Josep Palau i Fabre: Picasso. Cubism , 1998, p. 61

- ^ A b c d Judith Cousins: Comparative Biographical Chronology Picasso and Braque . From William Rubin: Picasso and Braque. The Birth of Cubism , 1990, pp. 343-345

- ^ Daniel Henry (Kahnweiler): Young art. André Derain , Verlag von Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1920, Leipzig, p. 7

- ^ A b Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler: The way to cubism . Verlag Gerd Hatje Stuttgart, first edition 1920, pp. 20–22

- ^ A b c d Judith Cousins: Comparative Biographical Chronology Picasso and Braque . From William Rubin: Picasso and Braque. The Birth of Cubism , 1990, pp. 340–342

- ↑ a b c d Anne Gantführer-Trier: Kubismus , 2007 pp. 11-14

- ↑ Carsten-Peter Warncke: Pablo Picasso , 1991, Volume 1, pp. 182-183

- ^ Bernard Zurcher: Georges Braque. Life and Work , p. 42

- ↑ a b c Judith Cousins: Comparative biographical chronology Picasso and Braque . From William Rubin: Picasso and Braque. The Birth of Cubism , 1990, pp. 346–347

- ↑ Jane Fluegel, William Rubin (Ed.): Pablo Picasso. Retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, New York , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1980, p. 89

- ^ Patrick O'Brian: Pablo Picasso. A biography . Ullstein, Frankfurt / M / Berlin / Vienna 1982, p. 201

- ↑ Siegried Gohr: I don't look, I find. Pablo Picasso - Life and Work . DuMont, Cologne 2006, p. 20 f

- ^ Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler: The way to cubism . Verlag Gerd Hatje Stuttgart, first edition 1920, pp. 27–28

- ^ Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler: The way to cubism . Verlag Gerd Hatje Stuttgart, first edition 1920, p. 25

- ^ A b Pablo Picasso: About Art Diogenes Verlag AG Zurich, Zurich 1988, p. 69

- ↑ Judith Cousins: Comparative Biographical Chronology Picasso and Braque . From William Rubin: Picasso and Braque. The Birth of Cubism , 1990, p. 349

- ^ Cubism ( Memento from December 30, 2010 in the Internet Archive ), Kunstwissen.de, accessed on April 3, 2011

- ↑ a b c Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler: The way to cubism . Verlag Gerd Hatje Stuttgart, first edition 1920, pp. 49–52

- ^ Carsten-Peter Warncke, Ingo F. Walther (Ed.): Pablo Picasso . Taschen Verlag, Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-8228-3811-2 , Volume 1, p. 180

- ↑ 1910, oil on canvas, 100 cm × 73 cm, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris

- ^ Carsten-Peter Warncke: Pablo Picasso , 1991, Volume 1, p. 194

- ↑ a b c d Anne Gantführer-Trier: Kubismus , 2007 p. 46

- ^ Daniel Henry (Kahnweiler): Young art. André Derain , Verlag von Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1920, Leipzig, p. 9

- ^ A b Anne Gantführer-Trier: Kubismus , 2007 p. 56

- ^ Anne Gantführer-Trier: Kubismus , 2007 pp. 16-18

- ^ Anne Gantführer-Trier: Kubismus , 2007 pp. 58, 68

- ↑ a b c Carsten-Peter Warncke, Ingo F. Walther (ed.): Pablo Picasso , Taschen Verlag, Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-8228-3811-2 , Volume 1, p. 206

- ↑ a b c d e f Anne Gantführer-Trier: Kubismus , 2007 p. 23 25

- ^ A b Albert Gleizes, Hans M. Wingler (ed.): Der Kubismus , Neue Bauhausbücher, Florian Kupferberg Verlag, Mainz 1980, ISBN 3-7837-0088-4 , p. 11

- ^ Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler: The way to cubism . Verlag Gerd Hatje Stuttgart, first edition 1920.

- ↑ Judith Cousins: Comparative Biographical Chronology Picasso and Braque . From William Rubin: Picasso and Braque. The Birth of Cubism , 1990, p. 350

- ↑ a b Judith Cousins: Comparative biographical chronology Picasso and Braque . From William Rubin: Picasso and Braque. The Birth of Cubism , 1990, pp. 358–359

- ^ Grace Glueck: Picasso Revolutionized Sculpture Too , NY Times, exhibition review 1982, accessed July 20, 2010

- ^ Cubism ( Memento of November 14, 2002 in the Internet Archive ), g26.ch, accessed on February 23, 2011

- ^ A b Anne Gantführer-Trier: Kubismus , 2007 p. 54

- ↑ Prague sights: Cubist architecture