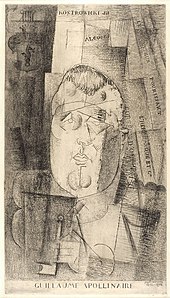

Guillaume Apollinaire

Guillaume Apollinaire , actually Wilhelm Albert Włodzimierz Apolinary de Wąż-Kostrowicki , (born August 26, 1880 in Rome , Italy , † November 9, 1918 in Paris ) was a French poet and writer of Italian-Polish descent. Especially with his poetry , he is one of the most important French authors of the early 20th century. He coined the terms Orphism and Surrealism .

Life

Childhood and youth in Rome and Monaco

Guillaume Apollinaire, as he was officially called after his naturalization in 1916, was born in Rome as Guglielmus Apollinaris Albertus Kostrowitzky, according to the baptism certificate. His grandfather Kostrowitzky was an emigrated Polish nobleman with Russian citizenship, who had entered the service of the Vatican in Rome and married an Italian. His mother, Angelica Kostrowicka, was the lover of a noble former officer of the dissolved Kingdom of Naples, Francesco Flugi d ' Aspermont , who is considered the father of Apollinaire and his younger brother Roberto, for many years .

Apollinaire (Italian-speaking) spent his childhood in Rome. He first spent his high school (now French-speaking) in Monaco , where his mother had moved in 1887 after Flugi d'Aspermont had ended the relationship with her in 1885 under pressure from his family. In 1895 Apollinaire or Wilhelm de Kostrowitzky, as he called himself at the time, moved to a high school in Cannes , and in 1897 to one in Nice . As a high school student he learned Latin, Greek and German, but did not pass the baccalauréat (Abitur). During those years, an uncle on his father's side who was a clergyman in Monaco took care of him and his brother.

In 1898 he spent reading and writing in Monaco, using various pseudonyms , including "Guillaume Apollinaire". At the beginning of 1899 the mother moved to Paris with a lover and their two sons. The family spent the summer in Stavelot in Belgium, where Apollinaire wrote poems with a Walloon influence on the innkeeper's daughter. His first attempts as a narrator also date from this time.

Years of apprenticeship in Paris

Back in Paris, he made a living from small jobs, including nègre , d. H. Ghostwriter of an established writer. In addition, he wrote his own texts: poems, a play that was accepted but not performed, and stories, including a pornographic commission.

In the summer of 1901 he traveled to the Rhineland with his English colleague Annie Playden, who was the same age . They accompanied Mme de Milhau, who came from Germany and owned property in and near Honnef , including the Neuglück house near Bennerscheid. During her stay there she employed Apollinaire for a year as a French teacher for her daughter. This period inspired him to write a series of mostly melancholy poems, some of which later became part of his main work, the Alcools collection . During two vacations in early and mid-1902, he traveled to Germany and reached Prague and Vienna via Berlin and Dresden. These journeys found their literary expression in poems and stories as well as in travel impressions for Paris newspapers.

After he had drawn his first poems accepted for print in 1901 as "Wilhelm Kostrowitzky", in early 1902 he chose the pseudonym "Guillaume Apollinaire" for his first printed story, L'Hérésiarque , which he used from then on.

Since returning to Paris in 1902 he worked as a small bank clerk. Two trips to London to win Annie Playden's favor were unsuccessful.

In addition to his office work, he wrote poems, stories, literary reviews and various journalistic texts. Gradually he found access to several of the then numerous Parisian literary magazines and made friends with various writers, in particular with Alfred Jarry .

In 1904 he was briefly editor-in-chief of a magazine for investors, Le Guide des Rentiers . In the same year he published the fairy-tale surrealistic, misogynous story L'Enchanteur pourrissant in a feature section . It was published as a book in 1909, supplemented by a new opening and closing section as well as woodcuts by André Derain .

In 1905 Apollinaire met Pablo Picasso and Max Jacob , through whom he came into the milieu of the Parisian avant-garde painters and grew into the role of an art critic. Now and then he also wrote pornographic texts, e.g. B. Les onze mille verges and Les exploits d'un jeune Don Juan (both 1907), and from 1909 was in charge of the book series Les Maîtres de l'Amour (Masters of Love) at a publisher , which he wrote with selected texts by de Sade ( who was still little known at the time) and Pietro Aretino opened.

The painter Marie Laurencin had an exhibition at Clovis Sagot in 1907, at which Picasso introduced her to Apollinaire. They entered into a stormy and chaotic relationship until Laurencin left him in 1912. In November 1908 both were participants in Picasso's banquet in honor of Henri Rousseau in the Bateau-Lavoir ; The occasion for the celebration was that Picasso had acquired a painting, the life-size portrait of a former friend of Rousseau's, the so-called Yadwigha . The well-known picture La muse inspirant le poète (Muse, inspiring the poet), which the “customs officer” Rousseau painted of both, was created a year later.

The time of maturity

In 1910 Apollinaire published under the title L'Hérésiarque & Cie. an anthology with the stories he has written so far: 23 mostly short, often darkly fantastic texts in the manner of ETA Hoffmann , Gérard de Nerval , Edgar Allan Poe and Barbey d'Aurevilly . The book was - unsuccessfully - nominated for the Prix Goncourt . From 1911 he was a member of the Puteaux group , which met with Jacques Villon , the brother of Raymond Duchamp-Villon , and Marcel Duchamp in Puteaux in the rue Lemaître to exchange their views on art. The meetings took place until 1914.

Under suspicion

In the summer of 1911, the friends Apollinaire and Picasso found themselves in an awkward position, because the Louvre's most famous painting , the Mona Lisa , had disappeared without a trace on August 21, 1911, and both of them came within the suspect's circle. During their investigation, the police came across a man named Géry Pieret, a Belgian adventurer who had lived with Apollinaire for a short time. As early as 1907, he had stolen two Iberian stone masks from the Louvre and sold them to Picasso through Apollinaire. On May 7, 1911, Pieret stole another figure and later brought it to the Paris-Journal to demonstrate how negligent the museum is with works of art. He also indicated that a "colleague" would soon also bring the Mona Lisa back. The newspaper then made a sensational report on August 30, offering 50,000 francs for the replacement of the Mona Lisa .

On September 5, Apollinaire and Picasso took the two sculptures acquired in 1907 to the Paris Journal , in the hope that that would settle the matter for them. Pieret had fled and wrote out of anonymity - allegedly from Frankfurt - letters to the Paris Journal in which he affirmed Apollinaire's innocence. However, the police suspected that Pieret belonged to an international gang of thieves who had also stolen the Mona Lisa . After a house search, Apollinaire was arrested on September 8 for harboring a criminal and custody of stolen property; he betrayed Picasso's involvement after two days. Although he was interrogated, he was not arrested. Apollinaire was released on September 12 and the trial against him was dropped in January 1912 for lack of evidence. The Mona Lisa was not found again until December 13, 1913 in Florence and returned to the Louvre on January 1, 1914. The thief was Vincenzo Peruggia , a picture framer for the Louvre.

Alcools

In 1912, Apollinaire decided to use the best of his previous lyrical texts to compose an anthology called Eau-de-vie (schnapps). On the already completed galley proofs he changed the title to Alcools and promptly erased the entire punctuation, which was not completely new at the time, but was only to become popular in the 1920s. The semi-official criticism of 1913 rated the entire volume negatively when it was published in April. Apollinaire, who had hoped for a breakthrough from him, reacted with aggressive formulations in literary and art theoretical articles. The counterattacks provoked him to duel demands, but these remained unrealized. The epoch-making success of the volume, which was also reflected in the setting of individual texts by Arthur Honegger , Jean-Jacques Etcheverry , Léo Ferré , Bohuslav Martinů , Francis Poulenc and Dmitri Shostakovich , was not to be seen by Apollinaire.

Shortly before Alcools (March 1913), he brought out a collection of magazine articles on art and artists, which was simply to be called Méditations esthétiques , but was given the more popular title Les peintres cubistes by the publisher and helped establish the new term Cubism . Apollinaire also coined the term Orphism in the Méditations to describe the tendency towards absolute abstraction in the painting of Robert Delaunay and others.

His stories from this period include the long novella Le Poète assassiné , which was only published in book form in 1916 together with a few shorter novels, and Les trois Don Juan .

In May 1914 he took part in the recording of a record with symbolist poetry with three poems from Alcools that he had spoken . Around the same time he began to write “ideograms”, pictorial poems which he later referred to as “ calligrammes ” ( figure poems ), a term first used by the writer Edmond Haraucourt .

The last few years

When the war broke out on August 1, 1914, Apollinaire was also infected by the general enthusiasm and celebrated the war with literature. He immediately volunteered, but was not accepted because his Polish grandfather came from what was then the Russian Empire and he was therefore a foreigner. In a second attempt in December, he applied for his naturalization, including a name change that would make his pseudonym his official name, and was then admitted to an officers' course. His love letters and poems from this time were addressed to a certain Louise de Coligny-Châtillon, with whom he fell in love shortly before he was called up, but then went more and more to a young Algerian-French woman whom he met on the return trip from a disappointing one Met Louise on the train (and with whom he got engaged personally in the summer of 1915 by letter and on a visit to her family on New Year's Eve 1915/16).

In the early summer of 1915, Apollinaire came to the front, initially to the artillery, where he was a little behind the front line and also found time to write. In November he was allowed to go right to the front, but after a brief fascination he was disillusioned with the dirt and misery of the trenches. In March 1916, a few days after his naturalization and change of name, a shrapnel injured his temple. He had to undergo multiple operations and was awarded a medal for bravery.

During the subsequent year-long convalescence leave, he tried to resume his old Parisian life with his head bandaged and in uniform. Despite his poor health and the war conditions, this worked relatively well. He finished works he had started, e.g. B. the collection of poems Calligrammes or the collection of short stories Le Poète assassiné . He also wrote the surrealist piece Les mamelles de Tirésias (edition June 1917, later turned into an opera by Francis Poulenc , premiere in 1947). He also gave lectures on contemporary poetry and was able to determine that it was meanwhile something in the Parisian literary scene. He dissolved his engagement at the end of 1916 on the grounds that his experiences at the front had changed him a lot.

Halfway recovered, Apollinaire wrote the novel La Femme assise in the spring of 1917 . In June he was reactivated, but was able to stay in Paris, where he served in the censorship department of the War Ministry. The artistic manifesto L'esprit nouveau et les poètes dates from this period . In the same year, together with Max Jacob and Pierre Reverdy, he founded the literary avant-garde magazine Nord-Sud , which went under in 1918.

In January 1918, Apollinaire had to go to a clinic for several weeks with pneumonia. He was then looked after by a young woman from the artistic milieu, Jacqueline Kolb, whom he spontaneously married in May.

A few months later he succumbed to the Spanish flu , which was rampant in Europe. He was buried in the Père Lachaise cemetery.

In his estate there were numerous poems and prose fragments that were printed in the following years and that cemented his position in literary history.

Appreciation

The Prix Guillaume Apollinaire has been awarded every year since 1947 . It distinguishes an independent and modern complete work in French. The winners are selected by a jury from the Académie Goncourt . The prize is one of the most important literary prizes in France and is endowed with a monetary amount between € 1,500 and € 3,500.

In 2016, the Musée de l'Orangerie in Paris showed an exhibition entitled Apollinaire, le regard du poète , for which a catalog was published.

Importance of the work

In his youth, Apollinare was influenced by symbolist poetry. His adolescent admirers Breton , Aragon and Soupault later formed the literary group of Surrealists. Apollinaire coined the term “ surrealism ”. He used it for the first time - several years before Breton's manifestos - in his program sheet for the Ballet Parade performed in May 1917 , albeit without a conceptual content, and then as a subtitle for the drama Les mamelles de Tirésias , published that same year . In the etymology , the term Apollinaire and Parade are assigned . Very early on he showed an originality that freed him from the influence of any school and made him a forerunner of the literary revolution at the beginning of the 20th century.

His art is not based on a theory, but on a simple principle: the creative process must result from imagination, intuition and thus come as close as possible to life and nature. For him, nature is “a pure source from which one can drink without fear of being poisoned”. The artist is not allowed to imitate nature , but should let it appear from his personal perspective. In an interview with Perez-Jorba in the magazine La Publicidad , Apollinaire argues that the influence of intelligence, i. H. the philosophy and logic of excluding from the artistic process. The basis of art must be true feeling and spontaneous expression. The artistic work is wrong in the sense that it does not imitate nature, but is endowed with its own reality.

Apollinaire refuses to turn to the past or the future: “You cannot carry your father's corpse with you everywhere, you give it up along with the other dead… And when you become a father, you shouldn't expect one of our children to stand up for that Giving up the life of our corpse. But our feet come loose in vain from the ground that contains the dead ”( Méditations esthétiques , part I:“ About painting ”).

Apollinaire calls for constant formal renewal ( vers libre , neologisms , mythological syncretism ).

indexing

Apollinaire's novel Die 11000 Ruten was indexed in 1971 in Germany by the Federal Testing Office for Media Harmful to Young People. The Munich public prosecutor confiscated editions in 1971 and 1987; in France the book was banned until 1970.

In 2010 the European Court of Human Rights justified its judgment in a process over a Turkish-language edition by stating that the work belongs to the European literary heritage and therefore does not fall under the obscenity paragraphs of Turkish criminal law. Seizure would contravene the article on freedom of expression in the European Convention on Human Rights.

Scientific reception

To deal with authors of the avant-garde in science, especially when they have only died a few years before, is unusual. It is all the more noteworthy that in the early 1930s a German literary scholar, Ernst Wolf at the Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn , wrote a dissertation on Apollinaire and put basic details about his biography in connection with his work. Wolf had previously outlined the structure of this dissertation in an article for the Mercure de France , which Eberhard Leube , editor of a new edition of Wolf's dissertation, outlined as follows:

“The positioning of the Rhine poems by Alcools and other works in the biographical context of Apollinaire's stay in the Rhineland has been based on the premise that these texts, even if they seem to name precisely the place where their sentimental imaginations crystallize, are not, as it were, 'tourist' 'Have the character of an image, but are in a certain sense landscapes of the soul, which are constituted by the overlaying of earlier personal experiences of the poet, including consciously used reminiscences, which extends to the point of identification. "

Leube makes it clear that this essay was preceded by a variety of research that led Wolf to documents that are now partly no longer traceable. This enabled Wolf to take the term “Rhine poems” much broader than “what seems to be given by Rhénane's small cycle in the Alcools. He was also the first to recognize the presence of the Rhine landscape in all of Apollinaire's works, which went far beyond the poems - that is, in the prose stories that were hardly noticed in the 1930s. [..] The newly acquired biographical clues also enable Wolf to conjugate the dates of the genesis of individual poems or, for example by identifying Annie Playden, to make connections within the literary work itself clear that had not been seen before him. "

As a Jew, Ernst Wolf had to leave the university after completing his dissertation and emigrated to Sweden in 1937 and later to the USA. After a few teething problems, he was finally able to begin a university career and work as a professor of Romance language and literature. The Apollinaire research no longer played a major role for him. Which is why the significance for today's Apollinaire research, which reverberates to this day according to Leube from Wolf's dissertation, should be cited:

“As an early and at least in Germany by far the first scientific monograph on Apollinaire, it initially expanded and stabilized the documentary fund of life and work in a central area and thus made a significant contribution to establishing the prerequisites for an adequate understanding of Apollinaire's work create. Nevertheless, the biographical approach never led Wolf to argue emotionally - on the contrary: his investigation is a pattern of strictly text-based analysis that takes place against the background of constant reflection on the inherent laws of the literary work, to which every process of reception must be subordinate. Such a methodological pre-understanding, to which many today take for granted something, was in the thirties, to put it in the words of a contemporary French critic: “le plus audacieux et le plus original”; Coherent scientific research only got under way in France after the Second World War. "

Works (selection)

Fiction

-

Les exploits d'un jeune Don Juan . Gallimard, Paris 2008, ISBN 978-2-07-042547-1 (EA Paris 1907)

- The exploits of a young don Juan. Novel . Area-Verlag, Erftstadt 2005, ISBN 3-89996-433-0 .

-

Les our mille verges ou Les amours d'un hospodar . Éditions J'ai lui, Paris 2006, ISBN 2-290-30595-2 . (EA Paris 1907)

- The 11,000 rods . Goldmann, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-442-44139-0 (A sexually revealing grotesque; with an essay by Elisabeth Lenk that emphasizes the grotesque character of the book).

-

L'enchanteur pourrissant . Gallimard, Paris 1992, ISBN 2-07-031948-2 (EA Paris 1909).

- The rotting wizard. Stories, letters, essays . Verlag Volk & Welt, Berlin 1991, ISBN 3-353-00830-6 .

- Le bestiaire ou le cortège d'Orphée . Eschig, Paris 2005, ISBN M-045-00462-0 (music by Francis Poulenc , EA Paris 1911).

-

Le bestiaire ou cortège d'Orphée , dessins d'Olivier Charpentier, Paris, Prodromus, 2006, ISBN 2-9526019-0-9

- The bestiary or suite of Orpheus. Texts . Leipziger Literaturverlag, Leipzig 2006 (illustrated by Raoul Dufy ). (online at: chez.com )

-

Alcools . Gallimard, Paris 2013, ISBN 978-2-07-045019-0 (with an essay by Paul Léautaud ; EA Paris 1913).

- Alcohol. Poems . Luchterhand, Darmstadt 1976, ISBN 3-472-61192-8 (bilingual edition).

- Poèmes à Lou . P. Cailler, Geneva 1955.

-

Le poète assassiné . Gallimard, Paris 1991, ISBN 2-07-032179-7 (text in English and French; illustrated by Raoul Dufy; EA Paris 1916).

- The murdered poet. Narratives . Verlag Wolke, Hofheim 1985, ISBN 3-923997-08-6 (EA Wiesbaden 1967).

-

Les mamelles de Tirésias . Opéra-bouffe en deux acts et un prologue . Heugel, Paris 2004, ISBN M-47-31162-7 (music by Francis Poulenc; EA Paris 1917).

- Tiresia's breasts . Drame surréaliste en deux actes et un prologue . Reclam, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-15-008396-6 (a comedy called "surrealist drama"; bilingual annotated edition). Preface, excerpt, (PDF; 316 kB)

-

L'esprit nouveau et les poètes . Altamira, Paris 1994, ISBN 2-909893-09-X (EA Paris 1918).

- The new spirit and the poets. Manifesto of the conference in Vieux Colombier, November 26, 1917 .

- Calligrams . Heugel, Paris 2004, ISMN M-047-31256-3 (music by Francis Poulenc; EA Paris 1918).

-

Le Flâneur des deux rives. Chroniques , Éditions la Sirène, Paris 1919.

- Strollers in Paris . Friedenauer Presse, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-932109-66-9 (translated by Gernot Krämer).

-

La femme assise. Chronique de France et d'Amérique . Gallimard, Paris 1988, ISBN 2-07-028612-6 (EA Paris 1920).

- The seated woman. Manners and wonders of the time; a chronicle of France and America . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt / M. 1992, ISBN 3-518-22115-9 (novel).

-

Le guetteur mélancolique . Gallimard, Paris 1991, ISBN 2-07-030010-2 (expanded reprint Paris 1952; edited by Robert Mallet and Bernard Poissonnier).

- The melancholy scout .

- L'hérésiarque et Cie. Stock, Paris 1984, ISBN 2-234-01710-6 (EA Paris 1910).

- Arch heretics & Co. stories . Verlag Das Wunderhorn, Heidelberg 2003, ISBN 3-88423-213-4 .

- Du coton dans les oreilles / cotton wool in the ears . Verlag Klaus G. Renner, Zurich 2009, ISBN 978-3-927480-59-9 (translated by Felix Philipp Ingold ).

- Poetry album 294 . Märkischer Verlag, Wilhelmshorst 2011, ISBN 978-3-931329-94-5 .

- The Soldier of Fortune and Other Tales . Dtv, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-423-19018-3 .

Non-fiction

-

Les peintres cubistes . Essays . Berg, Paris 1986, ISBN 2-900269-49-0 (EA Paris 1913).

- The Cubist Painters . Verlag die Arche, Zurich 1973 (reprint of the Zurich edition 1956; illustrated by Pablo Picasso and Maurice de Vlaminck ).

Work editions

- Marcel Adéma and Michel Décaudin (eds.): Œuvres poétiques (Bibliothèque de la Pléiade; vol. 121). Gallimard, Paris 1990, ISBN 2-07-010015-4 (EA Paris 1978).

- Pierre Caizergues et Michel Décaudin (eds.): Œuvres en prose . Gallimard, Paris 1988.

- 1988, ISBN 2-07-010828-7 (Bibliothèque de la Pléiade; vol. 267).

- 1991, ISBN 2-07-011216-0 (Bibliothèque de la Pléiade; vol. 382).

- 1993, ISBN 2-07-011321-3 (Bibliothèque de la Pléiade; vol. 399).

Correspondence

- Peter Beard (Eds.): Guillaume Apollinaire, Paul Guillaume. Correspondance 1913-1918 . Musée de l'Orangerie , Gallimard, Paris 2016.

See also

literature

Essays

- Riewert Ehrich: L'écho du rire de Jarry chez Apollinaire . In: Claude Debon (ed.): Apollinaire et les rires 1900 . Caliopées, Clamart 2011, ISBN 978-2-916608-16-7 , pp. 43-58 (Colloque International, Stavelot, August 30 to September 1, 2007).

- Wolf Lustig: "Les onze mille verges", Apollinaire between pornography and "esprit nouveau" . In: Romance Journal for the History of Literature , 10 (1986), 131–153.

- Klaus Semsch: Vertu et virtualité dans l'oeuvre de Guillaume Apollinaire. In: Habib Ben Salha et al. (Ed.): Ponts et passerelles. MC-Éditions, Tunis 2017, ISBN 978-9938-807-95-0 , pp. 73–91.

- Winfried Wehle : Orpheus' broken lyre. On the “poetics of making” in avant-garde poetry. Apollinaire, a paradigm . In: Rainer Warning, Winfried Wehle (Ed.): Poetry and painting of the avant-garde ; Romance Studies Colloquium II ( UTB ; 1191). Fink, Munich 1982, ISBN 3-7705-2077-7 , pp. 381-420. (PDF)

- Winfried Wehle: Apollinaire: Les Fenêtres (1915) - Manifesto of a 'completely new aesthetic' . In: Helke Kuhn, Betrice Nickel (ed.): Difficult readings: the literary text in the 20th century as a challenge for the reader. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2014, ISBN 978-3-631-65245-9 , pp. 15-30. ( PDF ).

- Achim Schröder: Alfred Jarry " Ubu Roi " 1896 and Guillaume Apollinaire "Les Mamelles de Tirésias" 1917. in Konrad Schoell (ed.): French literature. 20th century: Theater (Stauffenburg interpretation). Verlag Stauffenburg, Tübingen 2006, ISBN 3-86057-911-8 .

- Ernst Wolf : Guillaume Apollinaire en Rhénanie et les Rhénanes d'Alcools , in: Mercure de France , August 1933.

- Ernst Wolf : Le Séjour d'Apollinaire en Rhénanie , Mercure de France , June 1938.

- Ernst Wolf : Apollinaire and the "Lore-Lay" Brentanos. In: Revue de litterature comparée. October / December 1951

Monographs

- Jürgen Grimm: The avant-garde theater of France 1895–1930 . CH Beck, Munich 1982, ISBN 3-406-08438-9 .

- Jürgen Grimm: Guillaume Apollinaire . CH Beck, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-406-35054-2 .

- John Phillips: Forbidden Fictions. Pornography and Censorship in Twentieth-Century French Literature . Pluto, London 1999, ISBN 0-7453-1217-9 .

- Jean Firges : Guillaume Apollinaire. Rhénanes - Rhine songs. Poem Interpretations (Exemplary Series Literature and Philosophy; Vol. 30). Sonnenberg, Annweiler 2010, ISBN 978-3-933264-62-6 .

- Veronika Krenzel-Zingerle: Apollinaire readings. Speech frenzy in the "Alcools" (Romanica Monacensis; Vol. 67). Narr, Tübingen 2003, ISBN 3-8233-6005-1 (also dissertation, University of Munich 2002).

- Andrea Petruschke: Languages of fantaisie in French poetry around 1913. Stagings and reality and subjectivity in “Alcools” by Guillaume Apollinaire and the école fantaisiste . Tectum-Verlag, Marburg 2004, ISBN 3-8288-8697-3 (plus dissertation, University of Berlin 2003).

- Francis Steegmuller: Apollinaire. Poet among the painters . Hart-Davis, London 1963.

- Michael Webster: Reading visual poetry after futurism. Marinetti , Apollinaire, Schwitters , Cummings (Literature and the visual arts; Vol. 4). Peter Lang Verlag, New York 1995, ISBN 0-8204-1292-9 .

- Werner Osterbrink (ed.): The poet Guillaume Apollinaire and Honnef. World literature and Rhenish poetry 1901–1902 . Roessler Verlag, Bornheim 2008, ISBN 978-3-935369-16-9 (catalog of the exhibition of the same name, Kunstraum Bad Honnef, May 4 to June 1, 2008).

- Eugenia Loffredo, Manuela Perteghella (Eds.): One poem in search of a translator. Re-writing "Les fenetres" by Apollinair . Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt / M. 2009, ISBN 978-3-03911-408-5 .

- Laurence Campa: Guillaume Apollinaire , [Paris]: Gallimard, 2013, ISBN 978-2-07-077504-0

- Ernst Wolf : Guillaume Apollinaire and the Rhineland , with a preface by Michel Décaudin, edited by Eberhard Leube , Lang, Frankfurt am Main / Bern / New York / Paris, 1988, ISBN 978-3-8204-1408-0 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Guillaume Apollinaire in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Guillaume Apollinaire in the German Digital Library

- Works by Guillaume Apollinaire in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Articles in the Names, Titles and Dates of French Literature (main source for the Life and Creation section of this article)

- official site (french)

- Biography, bibliography, analysis ( Memento of January 14, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) (French)

- The color of tears - The First World War from the point of view of painters ( Memento from May 20, 2000 in the Internet Archive )

- Guillaume Apollinaire in the database of Find a Grave (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Marie Laurencin ( memento from June 30, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ), artsci.wustl.edu, accessed on September 3, 2013.

- ↑ www.tate.org: Henri Rousseau - Jungles in Paris. Archived from the original on January 11, 2006 ; Retrieved October 8, 2012 .

- ^ Judith Cousins, in: William Rubin, p. 364 f.

- ^ Antonina Vallentin: Picasso , Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 1958, p. 205 f.

- ^ Judith Cousins, in: William Rubin, note 119, p. 419.

- ^ Nicole Haitzinger: EX Ante: "Parade" under frictions. Choreographic concepts in collaboration with Jean Cocteau, Pablo Picasso and Léonide Massine , corpusweb.net, accessed on December 23, 2010.

- ↑ etymonline : Surréalism , accessed December 23, 2010.

- ↑ Collected prose works . Gallimard 1977, p. 49.

- ↑ Federal Testing Office for Media Harmful to Young People: Complete directory of indexed books, paperbacks, brochures and comics ; As of April 30, 1993.

- ^ First in court, then at the award ceremony , Spiegel online October 26, 2010.

- ^ Judgment of the European Court of Human Rights (French) , February 16, 2010.

- ↑ Eberhard Leube: Afterword by the editor , in: Ernst Wolf: Guillaume Apollinaire and the Rhineland , p. 196.

- ↑ Eberhard Leube: Afterword by the editor , in: Ernst Wolf: Guillaume Apollinaire and the Rhineland , p. 198

- ↑ Eberhard Leube: Afterword by the editor , in: Ernst Wolf: Guillaume Apollinaire and the Rhineland , pp. 199–200. The translation of the French quote is: the boldest and most original [methodological pre-understanding].

- ↑ Attached work: The eleven thousand rods .

- ^ Graphic by Henri Matisse on the 1917 program booklet.

- ^ Text on the server of the University of Duisburg-Essen

- ^ EA published under the title Il ya in Paris 1925.

- ↑ from: Alcools . 1901.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Apollinaire, Guillaume |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Wilhelm Albert Vladimir Apollinaris de Kostrowitzky (original name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French writer and art critic |

| DATE OF BIRTH | August 26, 1880 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Rome , Italy |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 9, 1918 |

| Place of death | Paris |