Marcel Duchamp

Marcel Duchamp (born July 28, 1887 in Blainville-Crevon , France , † October 2, 1968 in Neuilly-sur-Seine near Paris , France), actually Henri Robert Marcel Duchamp , was a French - American painter and object artist . He is a co-founder of conceptual art and is one of the pioneers of Dadaism and Surrealism . The Prix Marcel Duchamp is named after him.

Life

Early years

Henri Robert Marcel Duchamp was born in 1887 as the third of six children of the notary Justin-Isidore "Eugène" Duchamp (1848–1925) and his wife Marie Caroline Lucie Duchamp, a daughter of the painter, engraver and shipbroker Émile Frédéric Nicolle (1830–1894), Born in Blainville-Crevon near Rouen. Duchamp's eldest brother Gaston, known under the pseudonym Jacques Villon (* 1875), devoted himself to painting. His brother Raymond Duchamp-Villon (* 1876) was an important sculptor of Cubism . Of Duchamp's three sisters, Suzanne (* 1889), Yvonne (* 1895) and Magdelaine (* 1898), the oldest, Suzanne Duchamp , was also a painter. As a child he often played with Suzanne as the two older brothers attended school in Rouen . In 1896 Duchamp received his "Certificat d'étude primaire" at the elementary school in Blainville, in October 1897 he was a boarding school student at the École Bossuet in Rouen and received instruction at the Lycée Corneille . In 1902, at the age of 15, Duchamp began to paint. His first pictures were still influenced by the then prevailing impressionistic painting style. The following year he made sketches by his sister Suzanne and his grandmother, as well as by Robert Pichon, a painter and friend of the family from Rouen, among others.

Education

In July 1904 Duchamp received the "Baccalauréat de philosophie" at the Lycée Corneille in Rouen. Afterwards he went to the private art school Académie Julian in Paris for a few months , where he lived with his brother Jacques Villon at 71 rue Caulaincourt. During his studies at the academy, he mainly dealt with impressionist painting. In October 1905 he volunteered for the military and took advantage of a law that guaranteed doctors, lawyers, skilled workers and craftsmen a period of military service reduced from three to one year. He was able to prove his activity as a craftsman (ouvrier d'art), since he began an apprenticeship at the Imprimerie de la Vicomte from May 1905 in Rouen, where his parents had moved, which he successfully completed after five months. His graphic examination work consisted of printing press copies of an etching by his grandfather Émile Nicolle. After completing his military service in October 1906, he returned to Paris and took an apartment at 65 rue Caulaincourt. In the next few years he tried his hand at an illustrator.

First exhibitions

From July 1908 to October 1913 he lived in Neuilly near his older brother Jacques Villon, who lived in Puteaux . From 1911 onwards, artists and writers such as Albert Gleizes , Henri Le Fauconnier , Roger de La Fresnaye , Jean Metzinger and Guillaume Apollinaire came together in his garden on Sundays every Sunday ; the meetings led to the formation of the so-called Puteaux group .

In 1909 Duchamp took part in the exhibition of the Salon des Indépendants in Paris , which lasted from March 25 to May 2, with two pictures, one of which was the landscape from 1908. Duchamp contributed three works to the Salon d'Automne exhibition, which ran from October 1 to November 8 , including the works Auf den Klippen from 1908 and Saint Sébastien from 1909, which were included in the exhibition catalog at the time under the title Veules (Eglise) was performed. After drawing caricatures for several magazines for some time , he turned to Cubism like his brothers in 1911 . In the same year he became friends with Guillaume Apollinaire and Francis Picabia . Like Francis Picabia, Albert Gleizes, Juan Gris and his brother Jacques Villon, Marcel Duchamp was a member of the Section d'Or and the Puteaux group.

Style change from 1912

At the end of June 1912, at the suggestion of the German painter Max Bergmann , whom he knew from Paris , Duchamp went to Munich , where he stayed for almost three months (“My stay in Munich was the place of my complete liberation”). When he visited the Deutsches Museum and the Bavarian Trade Show , he found important technical details as inspiration for his work. He sent postcards from the Hofbräuhaus and the Nymphenburg Palace and had Heinrich Hoffmann photograph him.

He also often visited the Alte Pinakothek and saw the paintings by Lucas Cranach , which he valued and which had an influence on his last cubist painting The Bride , which he made in Munich . He also began the studies for The newlyweds / bride will be undressed by her bachelors, even (or: large glass) .

With Constantin Brâncuși and Fernand Léger , Duchamp visited the air show in the Paris Grand Palais in the autumn of 1912 . Duchamp remarked to Brâncuşi in view of the technical innovations: “Painting is finished. Who can do better than these propellers? Do you? ”In view of the perfect industrial shape, the visit had a similar effect on the group as African masks a little earlier had on Pablo Picasso . Duchamp gave up painting and created his first ready-made Roue de bicyclette ( bicycle wheel ) , Brâncuşi's polished sculptures approached the industrial form, while Léger dealt with the theory of how art could be made to add the beauty of machines to reach.

Duchamp's departure from “retinal painting” was accompanied by a turn to literary sources. “I felt that it was much better for a painter to be influenced by a writer than by another painter.” In May 1912 he accompanied his friend Apollinaire and Francis and Gabrielle Picabia to a performance of Raymond Roussel's play Impressions from Africa at the Théâtre Antoine in Paris. “It was fundamentally Roussel,” said Duchamp looking back in a conversation in 1946, “who was even responsible for my glass, The Bride naked by her bachelors .” Jean-Pierre Brisset's linguistics exerted another significant influence on Duchamp. "Brisset and Roussel were the two men I most admired in those years because of their fantasy delirium."

In early November 1912, the American artists Arthur B. Davies and Walt Kuhn visited Parisian galleries, studios and private collections, looking for works of modern art for their planned major exhibition, the Armory Show , in New York . They received help from the American painter Walter Pach , who had lived in Paris since 1907 and spoke fluent French and German. Pach gave them access to the painters' studios, introduced them to the art salon of Gertrude and Leo Stein , and introduced them to the Duchamp brothers in Puteaux. They selected several works by the brothers for the exhibition, including four by Marcel Duchamp. In April 1913, after successfully completing a course in library science , Duchamp began working as a library assistant at the Sainte-Geneviève library in Paris.

The Armory Show

After the painting Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2 (Nu descendant un escalier no.2) from 1912 was rejected by the Salon des Indépendants in Paris in the same year because it went beyond the program of the Cubists around Gleizes and Metzinger, the effects of the rejection were permanent for Duchamp: "It was a real turning point in my life," as quoted by his biographer Calvin Tomkins , who met him in 1959 during an interview for Newsweek . "I saw that afterwards I would never be too interested in groups".

A year later, Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) , which was painted by Duchamp in a cubist style with simultaneous futuristic elements and strongly influenced by Eadweard Muybridge's sequence of images Woman walking downstairs , was shown at the Armory Show in New York in 1913 . There the avant-garde styles of Europe from impressionism to abstract painting were represented for the first time in a large exhibition in the United States. Duchamp transformed the still image into an apparently moving one and thus sparked heated discussions; it made him a well-known personality in one fell swoop, as it provoked the American audience. Duchamp was not present at the fair; Francis Picabia was the only artist of the European avant-garde to be there with his wife Gabrielle, who told his friends about the great event. Duchamp's four exhibited works were sold, the last of which was the nude, descending a flight of stairs , for $ 342. The work is currently on display at the Philadelphia Museum of Art .

The first readymades

Duchamp's views radically questioned the current concept of art : As a readymade , Marcel Duchamp implemented the concept of the objet trouvé in his Fahrrad-Rad (1913), Bottle-Dryer (1914) and Fountain (1917). In 1914, for example, he bought an iron bottle dryer (Portes-bouteilles) in the Paris department store Bazar de l 'Hôtel-de-Ville and signed it. Bicycle wheel consists of a combination of wheel, bicycle front fork and wooden stool, in the case of the following, an industrially manufactured wire frame for bottle drying and a urinal are placed on a base and declared an art. He publicly took the opinion that the selection of an object was an artistic work, which led to an art scandal.

Relocation to New York

Duchamp left Paris in 1915 and moved to New York - he arrived there by ship on June 15 of that year - and stayed with Walter Pach for the first few days and then, through Pach's mediation, first moved into a double apartment at 33 West 67th Street, owned by art collector couple Louise and Walter Arensberg , who spent the summer in Pomfret, Connecticut . A month later he moved into a furnished room on Beekman Place and shortly thereafter a studio in the Lincoln Arcade Building on Broadway . Walter Conrad Arensberg and Louise Arensberg became his most important collectors.

The media discovered Duchamp. Recalling the Armory Show, the New York Tribune ran the headline, "The Act-Descending-a-Staircase-Man Inspects Us" on September 12th that year as the first newspaper. More posts followed in the fall, and interviewers were surprised that the specter of the show was so amiable.

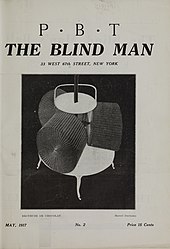

In New York Duchamp met his friend Francis Picabia again, who like himself and other artists such as Jean Crotti and Albert Gleizes had emigrated to America because of the First World War . In 1916 Duchamp founded the Society of Independent Artists together with other artists and in 1917, together with Henri-Pierre Roché and Beatrice Wood, published the early Dadaist publication The Blind Man , which appeared in two editions in April and May of that year.

Also in 1917, Duchamp moved into a small studio at 33 West 67th Street, where he worked until July 1918. From the beginning of 1918 he painted his last oil painting on canvas with the title Tu m ' , interpreted as “tu m'emmerdes” (“you get on my nerves”). He created it on behalf of Katherine Sophie Dreier, who wanted to decorate a long, narrow area in her library with it. On August 13, 1918, he left for Buenos Aires , where he stayed until June 1919. There he played chess intensively, drew chess players and made detailed studies for the large glass , which "can be viewed closely with one eye for almost an hour".

Back in Paris

From 1919, back in Paris, he met André Breton , Louis Aragon , Paul Éluard , Philippe Soupault and Jacques Rigaut , poets from the circle of the Dadaists and later Surrealists . At that time Duchamp was working on the readymade LHOOQ , a reproduction of the Mona Lisa to which he had added a mustache and goatee.

| Man Ray: |

|

Duchamp as "Rrose Sélavy" , 1920–1921 |

| Philadelphia Museum of Art |

| Marcel Duchamp: |

|

Why not Sneeze, Rose Sélavy? , Readymade, 1921 (replica 1964) |

| Tate Gallery of Modern Art |

| (External links, please note copyrights ) |

Also in 1919 Duchamp adopted the pseudonym Rose Sélavy, to which he added a second "r" to the word Rose in the middle of the next year and changed it to Rrose. Some of his works were marked with this name. The name means in French pronunciation of the sequence of letters "Eros, c'est la vie" ("Eros, that is life"). Man Ray also gave the name Rrose Sélavy to a series of photos he created of Duchamp around 1921, in which he was portrayed dressed as a woman. In the same year Duchamp created the readymade Why not Sneeze, Rose Sélavy? (Why not sneeze, Rose Sélavy?) , Consisting of a birdcage filled with 152 marble sugar cubes and a piece of sepia peel.

In 1920 Duchamp founded the “ Société Anonyme Inc. ” together with Katherine Sophie Dreier and Man Ray and came into contact with other artists of the avant-garde. In 1923 he met the American widow Mary Reynolds in Paris, whom he already knew from New York; he had a longstanding relationship with her until her death in 1950. She became a well-known bookbinder whose works are shown in the "Mary Reynolds Collection" at the Art Institute of Chicago . On June 8, 1927, Duchamp married Lydie Sarazin-Levassor (1903–1988), but they divorced six months later. It was rumored that Duchamp married for financial reasons, since Lydie was the granddaughter of the wealthy automobile manufacturer Émile Levassor . Lydie Sarazin-Levassor recorded her memories of her brief marriage to Duchamp over 50 years later; they were only published posthumously in 2004 and a German translation was published in 2010.

He gave up painting around 1928 and since then has mainly worked as a writer and organizer of exhibitions. In 1933 he and Mary Reynolds discovered the Spanish holiday resort of Cadaqués , where they met Salvador Dalí and his wife Gala and Man Ray. Since then, Cadaqués has been one of his favorite vacation spots, he has visited it eleven times since then and was supposed to celebrate his last birthday there.

In 1936 Duchamp took part in the exhibition "Phantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism" organized by Alfred H. Barr jun. at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. A year later, Breton opened a surrealist gallery under the name “ Gradiva ” at 31 rue de Seine in Paris, but it was closed again after a short time. Marcel Duchamp designed the entrance to the gallery, the glass door of which was decorated with a silhouette of a couple walking arm in arm. In this context he met Wolfgang Paalen , who designed the wooden frieze on the window frame. In 1938 Breton organized the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme in the Galerie Beaux-Arts in Paris, together with Éluard, Paalen and Duchamp as the “impulse referee” (“générateur-arbitre”) . There his decoration of the main room, 1200 sacks of coal hanging from the ceiling, was shown. His works on display also included Rrose Sélavy , a life-size female mannequin wearing Duchamp's clothes. Duchamp advised Peggy Guggenheim , whom he had known from Paris since the 1920s, on the opening of her Guggenheim Jeune gallery in London , which was held in January 1938 with a Jean Cocteau exhibition . A complete introductory course in modern art by Duchamp was required beforehand, because Guggenheim, as she confessed, had no prior knowledge of it. On the recommendation of Marcel Duchamp, Peggy Guggenheim gave Wolfgang Paalen a solo exhibition in her London gallery in March 1939. It was also Duchamp who recommended Paalen to the New York gallery owner Julien Levy , who in March 1940 exhibited Paalen's surrealistic pictures from Paris and some new works on paper from Mexico in his new gallery at 15 East 57th Street.

Back in New York

In 1942 Duchamp left France because of the Second World War and emigrated to New York. Mary Reynolds had preferred to stay in Paris, where she joined the Resistance , and arrived in New York in April 1943 after being persecuted by the Gestapo after an adventurous escape across the Pyrenees . Shortly before the end of the war, she returned to Paris alone.

Duchamp organized together with André Breton and with the participation of artists such as Max Ernst , Alexander Calder and David Hare the exhibition " First Papers of Surrealism ", which took place from October 14 to November 7, 1942 at the Whitelaw Reid Mansion. He furnished the exhibition rooms with a huge spider web made of twine, which did not spare the exhibited works, so that some of them were barely recognizable. In the same year he co-founded the surrealist magazine VVV in New York.

In 1945 Duchamp designed the bindings for the Marcel Duchamp special issue of View magazine and for the Man-Ray catalog for the exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery in April 1945. In 1946, Duchamp was a member of the jury of the Bel Ami art competition alongside Alfred H. Barr jun. and Sidney Janis , who was put out to tender for the American film The Private Affairs of Bel Ami by its producer. The jury selected the picture The Temptation of St. Anthony by Max Ernst as the winner of the competition. Mary Reynolds, Duchamp's long-time partner, died on September 30, 1950 in Paris. Duchamp had come from New York to spend the last days of her life with her and after her death took responsibility for the liquidation of the household. He sent her artistic estate and the collection of numerous Dadaist and surrealist documents to Reynolds brother Brookes Hubachek, who was to donate it to the Ryerson & Burnham Libraries of the Art Institute of Chicago .

In 1952 Duchamp was accepted into the Collège de 'Pataphysique , which had been founded in Paris in 1948 in honor of the French writer Alfred Jarry . He married again on January 16, 1954: his second wife Alexina Duchamp , called Teeny, had previously been married to Pierre Matisse , the well-known gallery owner in New York and son of the painter Henri Matisse . They had met before, but only knew each other briefly. Duchamp had seen her again in 1951 at the invitation of Max Ernst and his wife, Dorothea Tanning , during a visit to Alexina's house in Lebanon, New Jersey , and they fell in love. He became an American citizen on December 30, 1955. In 1962 Duchamp became a member of the international authors' association Oulipo .

Last years

In 1963 the first Duchamp retrospective took place at the Pasadena Art Museum under the direction of curator Walter Hopps . The opening with a total of 114 plants was on October 7; many Californian artists were among the visitors who viewed Duchamp as a "veritable hero". Andy Warhol was also one of the visitors to the opening exhibition. Hopps had occupied seven rooms with the exhibition. The first room contained photos and posters, the second room was designed like a salon at the beginning of the 20th century and contained drawings by Duchamp for Le Rire as well as some paintings from the Fauvist period such as the portrait of his father as the centerpiece. The third room displayed portable chess sets he had designed, as well as drawings and paintings on the subject of chess. The following room was designed in a cubist way and showed two versions of his nude, descending a staircase (versions two and three), the portrait (Dulcinée) , king and lady, surrounded by quick nudes , the transition from the virgin to the bride and the bride . The highlight was the extra white painted hall, in the middle of which there was a copy of the large glass and the replicas of his most important ready-mades such as The Bottle Dryer and Fountain . The last two rooms showed Duchamp's optical works such as rotor reliefs and boxes in a suitcase, as well as some ancillary works.

Duchamp was a participant in documenta III in Kassel in 1964, and in the following year he exhibited at the Kestner Society in Hanover under the title Marcel Duchamp, même . In 1967, Duchamp helped organize an exhibition at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Rouen, Les Duchamps: Jacques Villon, Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Marcel Duchamp, Suzanne Duchamp .

On the night of October 1st to 2nd, 1968, Duchamp died after a happy evening with his wife Teeny and friends Robert and Nina Lebel as well as Man Ray and wife Juliet in his apartment in Neuilly, rue Parmentier No. 5, an apartment, that he had inherited from his sister Suzanne. Teeny found her husband dead in the bathroom just before one in the morning. Duchamp had decreed in his will that there should be no funeral service. His ashes were buried in a family grave on the Cimetière Monumental de Rouen . He had designed the text for his epitaph himself: "D'ailleurs c'est toujours les autres qui meurent" ("Besides, it is always the others who die").

Duchamp was represented posthumously in Kassel at documenta 5 (1972) and documenta 6 in 1977 with works.

plant

overview

After Duchamp's stay in Munich in 1912, there was a drastic change in his work. If he had previously been a painter in the context of the prevailing traditions of the western world, including the avant-garde styles from Post-Impressionism , Fauvism to Cubism , which he had passed through, from then on he rejected the traditional methods and materials. It was replaced by mechanical drawing, ironic texts and experiments that used chance as a substitute for the artist's conscious control. Duchamp disparagingly referred to conventional painting as "retinal" while he was on the way to transition from one mental or psychological state to another through his interest in movement.

Act, descending a flight of stairs No. 2

The painting Nude Descending Stairs No. 2 , exhibited at the Armory Show in 1913, sparked discussion among the audience. For Duchamp, who had not anticipated the scandal success, the conventional canvas painting, which he described as " olfactory masturbation ", was done.

“For me, painting is out of date. It's a waste of energy, not a good scam, not practical. We now have photography, cinema - so many other ways of expressing life. "

The big glass

| Marcel Duchamp |

| The newlyweds / bride are undressed by their bachelors, even (or: large glass) , 1915–1923 |

| (External link, please note copyrights ) |

The radical break with the contemporary art around him took place in 1912 during a lonely long stay in Munich . In 1915 he began his work The newlyweds / bride is undressed by her bachelors, even (or: large glass) (La Mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même) . Duchamp spent a great deal of time conceptualizing this work and mentions it repeatedly in his notes. The term “ bachelor machine ” from Duchamp's “Notes and Projects for The Large Glass” (1914–1923) took on a meaning in the history of philosophy. Duchamp called the lower part of his large glass the “bachelor machine” .

In 1921, Katherine Sophie Dreier acquired the large glass from the Arensberg family. In 1923 Duchamp stopped working on it, it remained unfinished. The large glass was first exhibited in the Brooklyn Museum in 1926/1927 . The work broke during the return transport. Several years later, in 1936, Duchamp repaired it and incorporated the fragmentation into the work by reassembling it so that the traces remained visible.

The large glass consists of a painted, vertical two-part large glass plate. The horizontal joint in the middle forms the horizon . The bride in the upper part presents itself as a kind of machine that has no human features - a further development of the act of going down a staircase . To the right of her is the inscription or Milky Way . In the lower part of the glass are the bachelors on the left , specifically these are priests , corpse bearers , station master , policeman , lackey , cuirassier . With their desire for the bride, they set the chocolate grater going right next to it, a motif that had always fascinated Duchamp. The work works like an experimental arrangement, the bachelors desire the bride without getting hold of her ( Eros ), it is self-referential and at first appears cryptic. The large glass was supposed to evoke a “marriage of mental and visual reactions”, be at the same time representation and idea .

In 1963, on the occasion of the retrospective at the “Pasadena Art Museum”, Duchamp had himself photographed by the American photographer Julian Wasser while playing chess with a naked woman, the 20-year-old student Eve Babitz , in front of this work . The photography demonstrates the temporary end of his artistic activity, as a result of which Duchamp devoted himself to the art trade and increasingly to the game of chess. Julian Wasser's photo series became world famous, widely reproduced and even attracted some attention in the chess world. Duchamp won the first game against Babitz in three moves.

Duchamp provided explanations of the large glass and other ideas in the text fragments of the Green Box from 1934. The words should be “not just communication”, but a direct component of art, “like a color”, according to Duchamp.

“It [the Green Box ] just presents preparatory notes about the Big Glass , and even these not in the final form, which I had somehow conceived analogous to a Sears Roebuck department store catalog that would have been included with the glass and was just as important as the visible material . "

The readymades

In 1913 he introduced the “first ready-made, not one created by the artist, but rather an everyday object chosen by him without any aesthetic prejudice (and different from the objet trouvé )” , but it was not until 1915/16 that he coined the term ready- made. The ready-made bottle dryer , created in 1914, was a mass-produced, industrially produced object, i.e. in the eyes of most a rather worthless object, the shape of which, detached from its function, had its own characteristic, which, however, had previously been - up to Duchamp's gesture of signing and the The meaning he gave it - remained invisible, so to speak. Duchamp's gesture is seen as "the birth" of conceptual art . Actions such as the veiling of the Reichstag of Christ are part of this tradition: by veiling something ordinary only becomes really visible again.

In 1917 Duchamp obtained a urinal and urinal for public lavatories from the New York company "JL Mott Iron Works", a dealer in sanitary supplies , gave it the title Fountain , signed it with the pseudonym "R. [ichard] Mutt" and submitted it under this pseudonymized artist name for the annual exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in New York. His submission was hotly debated because with it Duchamp deliberately violated all the 'rules' of traditional art and thus provoked the rejection of his work by the jury of the exhibition, to which he himself belonged and from which he left after the rejection of the work. The object lost today has been authentically handed down through a photograph by Alfred Stieglitz in the second edition of The Blind Man (New York, May 1917).

The group around Marcel Duchamp caused publicity. Fountain was thus "exhibited" - but not in the conventional sense: Fountain became a media event. Most of the art historians see Marcel Duchamp as the inventor of the readymade and art revolutionary, and the work “Fountain” as a central work of art history , with which he ironically questioned all previous art terms. Besides being a provocation, Duchamp's “Fountain” can also be seen as a reaction to increasing trust in the rationality of people. For a long time, however, there have been well-founded indications that Fountain could not have come from Duchamp, but from his girlfriend Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven .

In 1919 Duchamp worked on the readymade LHOOQ , a reproduction of the Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci , the 400th anniversary of which was celebrated that year. He added a mustache and goatee to the reproduction in pencil. According to Duchamp's paronomasia , the work can be read in two ways: on the one hand, the individual letters of the French title can be read as pronounced “elle a chaud au cul” (“she has a hot ass”), and on the other hand, “reveals a different anxiety by adding male attributes to one of the most famous and most superstitiously revered portraits of women, alluding to a subtle joke about Leonardo's own homosexuality and Duchamp's interest in the confusion of the sexual role. " A predecessor to this work was Sapeck's caricature of the Mona Lisa, entitled La Joconde fumant la pipe (La Gioconda, smoking a pipe) from 1887.

1921 created Duchamp Belle Haleine - Eau de Voilette (Beautiful Breath - Schleierwasser) - a perfume bottle. Following the pattern of the Parisian perfumer Rigaud, he provided a pattern for the Un air embaumé brand with a new label. He stuck the reduction of Man Ray's photograph Rrose Sélavy into the medallion on the bottle over the lettering "Belle Haleine" , and so the artist signed the bulbous original packaging. This readymade was considered lost for a long time, reappeared in the estate of Yves Saint Laurent in 2009 and auctioned off at Christie's for 7.9 million euros . In January 2011 it was exhibited for 72 hours in the Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin . It is one of the few originals that have survived from Duchamp's readymades, most of which have been thrown away or destroyed and only exist as replicas from the 1960s.

Duchamp used his readymades as a kind of counter-art, because he was of the opinion that the artist is always dependent on society and, due to its corruption, can never develop freely. This also led to its importance being measured more in terms of theoretical than artistic work. With his works he criticized conventional taste and challenged the viewer to rethink their previous definitions of 'art' and possibly to recognize the futility of art in the previous sense.

“I created them with no intention of rejecting any other intention than ideas. Every readymade is different. There is no common denominator between the […] readymades, except that they are manufactured goods. As for tracking down a guiding principle: no. Indifference. Indifference to taste: neither taste in the sense of photographic reproduction nor taste in the sense of well-made material. The common point is indifference. "

Many artists after him took up these ideas, including Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg , which is why Duchamp is often referred to as a co-founder of modern art .

In 1997, in her publication Marcel Duchamp's Impossible Bed and Other 'Not' Readymade Objects: A Possible Route of Influence From Art to Science, the American sculptor Rhonda Roland Shearer hypothesized that Duchamp would use a photo montage to reproduce his own portrait as a 25-year-old the Mona Lisa inserted. He also worked on other readymades and not just bought and signed them.

Box in a suitcase

From 1935 to 1941 Duchamp developed his idea of a portable artists' museum , a Boîte-en-valise (box in a case), as a deluxe version in 20 boxes with a leather cover. They each contained 69 reproductions of his works with slight differences in design and content. The small objects found their place in the box thanks to a specially developed folding system. In the box "his works of art, created since 1910, were made available and presentable at any time in miniaturized and reproduced form". A boîte-en-valise was exhibited by Peggy Guggenheim in her Art of This Century gallery in New York in 1942. A later edition, consisting of six different versions, was created in the 1950s and 1960s; The suitcase was replaced by differently colored fabric and the number of works in it varied.

Given: 1. The waterfall, 2. The luminous gas

As Duchamp's last work, a spatial object with the title Etant donnés: 1 ° la chute d'eau / 2 ° le gaz d'éclairage was created over twenty years of work . Behind an old wooden door and a broken brick wall as a frame, a reclining female nude is set up. The body lies on brushwood, the woman's arm holds an old-fashioned gas lamp parallel to her left thigh. A small, bright waterfall can be seen in the background. The hilly, wooded landscape is an overpainted photo montage , the life-size female body is made of plaster of parchment and painted parchment. The woman's face is covered by a blonde wig, the woman's feet and right arm were also not constructed. The woman's thighs are open, her sex is naked. The scenery can only be viewed in the museum through two peepholes in the door.

| Marcel Duchamp |

| Etant donnés , 1946–1966 |

| (External link, please note copyrights ) |

The diorama- like spatial object made of a wide variety of materials was gradually created from 1946 to 1966 in Duchamp's Greenwich Village studio. After Duchamp's death, it was opened to the public by the Philadelphia Museum of Art in June 1969 . According to Duchamp's will, there was no formal opening; his last installation was to quietly take its place among the holdings of the Walter Conrad Arensberg collection. The first study for his work is the pencil drawing by the Brazilian sculptor Maria Martins, dated 1947, his lover from 1946 to 1951. The torso is said to have been shaped after her and after his second wife, Alexina (Teeny) Duchamp, the left arm and the Hand holding the gas lamp and the blonde hair.

chess

Between 1928 and 1933 he was mainly concerned with chess , he took part with the French national team in the unofficial Chess Olympiad in Paris in 1924 and four official Chess Olympiads : 1928 in The Hague, 1930 in Hamburg, 1931 in Prague and 1933 in Folkestone. In addition, he dealt theoretically with the game and published together with Vitali Halberstadt in L'opposition et les cases conjuguées sont réconciliées a treatise on pawn endings .

What fascinated him about the game of chess was both the intellectual abstraction and the visual aspect created by the movements of the chess pieces on the board. He also appreciated the lack of a social purpose. Chess enabled him to withdraw from the art world.

In a speech at the Cazenovia Chess Congress in 1952, Duchamp said: "Through my close contact with artists and chess players, I came to the personal conclusion that not all artists are chess players, but all chess players are artists."

His interest in the game of chess was also reflected in many of his artistic work. Among other things, he designed the poster for the chess championship of France in 1925, processed his game record against Savielly Tartakower in Chess Score (1965) and held a performance entitled Reunion on March 5, 1968 in Toronto together with John Cage . The two played a game of chess, in which sensors in the chessboard triggered tone sequences.

Movie

In René Clair's short film Entr'acte from 1924, Duchamp played chess with Man Ray on the roof of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées while Francis Picabia splashed them with water.

In 1926 Duchamp finished working on his experimental film Anémic Cinéma , which was shot in Man Ray's Paris studio with the help of filmmaker Marc Allégret . It was a seven-minute animation of nine word games published for the art trade under his pseudonym Rrose Selavy. The letters were written in a spiral pattern on black disks and glued to spinning records; they took turns with recordings of his “rotor reliefs”. These were ten abstract drawings, the rotation of which resulted in a forward and backward moving erotic rhythm.

Duchamp was in several films by Dadaist Hans Richter responsible, in Dreams That Money Can Buy (sell dreams) from 1947. Richter realized the drafts of his fellow artists such as Duchamp, Max Ernst and Man Ray. Duchamp had an act descend a flight of stairs in his sequence to the background music by John Cage . Two other collaborative works followed: 8 × 8: A Chess Sonata in 8 Movements (1956/57), a film about the game of chess in which Marcel Duchamp also took part alongside Jean Cocteau , Paul Bowles , Alexander Calder and Jacqueline Matisse . Duchamp and artists of the Dada movement such as Hans Arp , Raoul Hausmann and Richard Huelsenbeck contributed to Richter's last work Dadascope (1961), a film with poetry and prose .

Andy Warhol turned 1966 a twenty-minute film about Duchamp entitled Screen Test for Marcel Duchamp (screen test) . Duchamp sat in the armchair during the recording and smoked a cigarette.

reception

| Joseph Beuys |

| Marcel Duchamp's silence is overrated , 1964 |

| (External link, please note copyrights ) |

On December 11, 1964, Joseph Beuys carried out the action The silence of Marcel Duchamp is overrated in the course of a live broadcast by ZDF in the state studio in North Rhine-Westphalia . The title of the action contains, on the one hand, “criticism of Duchamp's concept of art and also of his later behavior and its cultivation when he gave up art and only pursued chess and writing.” On the other hand, at that time, in the mid-1960s, among the Fluxu's close or affiliated artists controversial debate on whether one should join the Duchamp tradition under the rubrum Neo-Dada .

In his book about Beuys 'actions, Uwe M. Schneede shows another connection between this action and Duchamp's ready-mades by transferring Beuys' work Stuhl mit Fett , which was created a year earlier, to the ready-made practice.

The focus of the action was a right-angled wooden shed, open on one side, set up in the television studio. Beuys, "pulling a felt blanket with him, entered the field of action, put down the felt blanket, took the individual packs from a margarine carton and stacked them." Then Joseph Beuys placed a fat corner in the corners of the crate. On the floor in front of the wooden corner was a square plate with the words MARCEL DUCHAMP'S SILENCE IS OVERVALUED written in brown , underlining DUCHAMP .

| Richard Hamilton |

| Typo / Topography of Marcel Duchamp's Large Glass , 2003 |

| (External link, please note copyrights ) |

British pop artist Richard Hamilton began reconstructing Marcel Duchamp's Le Grand Verre in 1965 .

On March 10, 1968, Merce Cunningham and his dance company performed the piece Walkaround Time , which was equipped with a stage set designed by Jasper Johns based on motifs of the large glass .

The Welsh object artist Bethan Huws refers in her "object showcases" to Marcel Duchamp, among others, to his readymade fountain .

The French object and installation artist Saâdane Afif , who received the Marcel Duchamp Prize in 2009 , began his work Fountain Archive that same year . Continued to this day, it currently consists of around 300 pictures of Marcel Duchamp's urinal . Each of these images was taken from all kinds of publications - from books, through newspapers, magazines and encyclopedias to pornographic magazines. Afif integrates the individual cut-out sheet pages into specially adapted picture frames with partly colored back walls, making the frame an integral part of the entire picture. The installation then takes place in accordance with the architectural ambience.

research

In 2009 the Duchamp Research Center was founded in the State Museum in Schwerin . Since then, artists and scientists from all over the world have been invited to examine the works from the collection of the Schwerin State Museum and to discuss their research results. In addition to exhibitions on the work of Marcel Duchamp, the activities of the research center also include lecture series and scientific conferences as well as publications within the framework of the POIESIS series that show different facets of Duchamp's research. In addition, the Friends of the State Museum Schwerin e. V. announced the Duchamp research grant; 500 euros per month are paid for one year.

Appreciations

In 1953 the Collège de 'Pataphysique awarded him the title of Satrape . In 1960 he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters . 1977 appeared as a fragment Victor , a novel about Marcel Duchamp, written by Henri-Pierre Roché , with a foreword by René Clair . It was published posthumously by the Center national d'art et de culture Georges Pompidou , Paris.

The Prix Marcel Duchamp has been named after Marcel Duchamp since 2000 and is endowed with 35,000 euros. It is awarded annually by the Association pour la Diffusion Internationale de l'Art Française (ADIAF) to French artists or artists living in France. The ADIAF is one of the most important associations of lovers, patrons and collectors of contemporary art in France. The award is organized and carried out by the Musée d'Art Moderne in the Center Georges-Pompidou in Paris .

In a 2004 survey of 500 art experts, Duchamp's Readymade Fountain was voted “most influential modern art work of all time”. It was in front of Pablo Picasso's painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon and Andy Warhol's Marilyn Diptych .

In Paris, a street in the 13th arrondissement is named after him.

Works (selection)

|

literature

expenditure

- Arturo Schwarz (Ed.): The complete Works of Marcel Duchamp. Thames and Hudson, London 1969.

- Exhibition catalog Marcel Duchamp, même. Kestner Society, Hanover 1965.

- Marcel Duchamp: The writings. Volume I. Texts published during his lifetime. Edited by Serge Stauffer . Rainbow, Zurich 1981.

- Serge Stauffer : Marcel Duchamp. Interviews and statements . Collected, translated and annotated by Serge Stauffer. Edited by Ulrike Gauss . State Gallery of Stuttgart graphic collection. Edition Cantz, Ostfildern-Ruit 1992.

Secondary literature

- Stefan Banz (Ed.): Marcel Duchamp and the Forestay Waterfall , JRP-Ringier, Zurich 2010, ISBN 978-3-03764-156-9 .

- Jürgen Claus : Marcel Duchamp . In: Jürgen Claus: Theories of contemporary painting , Rowohlt, Reinbek 1963

- Dieter Daniels: Duchamp and the others. The model case of an artistic impact history in the modern age, Cologne 1992.

- Sebastian Egenhofer: abstraction, capitalism, subjectivity. The truth function of the work in modern times. Wilhelm Fink, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-7705-4397-7 .

- Vlastimil Fiala: The chess career of Marcel Duchamp . Moravian Chess, Olomouc, Vol. 1: 2002, ISBN 80-7189-420-6 ; Vol. 2: 2004, ISBN 80-7189-516-4 .

- Lydie Fischer Sarazin-Levassor: My marriage to Marcel Duchamp. Piet Meyer Verlag , Bern 2010, ISBN 978-3-905799-07-1 .

- Sherin Hamed: The Invisible Color. The use and function of titles in Marcel Duchamp's early work . LMU Publications, Munich 2004 ( full text )

- Dalia Judovitz: Unpacking Duchamp: Art in Transit . University of California Press , Berkeley 1995

- Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen (Hrsg.): Insights. The 20th century in the North Rhine-Westphalia Art Collection, Düsseldorf. Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern-Ruit 2000, ISBN 3-7757-0853-7 .

- Heinz Herbert Mann: Marcel Duchamp 1917. Silke Schreiber, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-88960-043-3 . (Representation of the events around Fountain )

- Bernard Marcadé: Marcel Duchamp: la vie à crédit; biography . Flammarion, Paris 2007, ISBN 978-2-08-068226-0 .

- Janis Mink: Duchamp . 3. Edition. Taschen, Cologne 2006, ISBN 3-8228-0883-0 .

- Herbert Molderings: Marcel Duchamp . 2nd edition, Campus, Frankfurt 1987, ISBN 3-88655-178-4 ; 3rd edition, Richter, Düsseldorf 1997, ISBN 3-928762-63-X .

- Herbert Molderings: The naked truth. On the late work of Marcel Duchamp , Hanser, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-446-23872-5 .

- Herbert Molderings: About Marcel Duchamp and the aesthetics of the possible , Walther König, Cologne 2019, ISBN 978-3-96098-478-8 .

- Francis M. Naumann: Marcel Duchamp. The Art of Making Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Harry N. Abrams, New York 1999, ISBN 0-8109-6334-5 .

- Octavio Paz : Naked Apparition. The work of Marcel Duchamp . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1991, ISBN 3-518-38333-7 .

- Henri-Pierre Roché: Victor. A novel. (Fragment of a novel about Duchamp). With a foreword by Jean Clair. Translated from the French by Simon Werle. Schirmer – Mosel, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-88814-211-3 .

- Jerrold Seigel: The Private Worlds of Marcel Duchamp: Desire, Liberation, and the Self in Modern Culture . University of California Press, Berkeley 1995.

- Werner Spies : Duchamp died of a laughing fit in his bathroom . Hanser, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-446-20581-0 .

- Theo Steiner: Duchamp's experiment. Between science and art . Wilhelm Fink Verlag, Munich 2006, ISBN 978-3-7705-4303-8 .

- Ernst Strouhal : Duchamp's game . Special number, Vienna 2010, ISBN 978-3-85449-066-1 .

- Calvin Tomkins : Marcel Duchamp. A biography . Hanser, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-446-20110-6 .

- Karina Türr : Marcel Duchamp's “Fountain”. In: Karl Möseneder (Ed.): Dispute about images. From Byzantium to Duchamp. Dietrich Reimer, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-496-01169-6 , pp. 221-235.

Web links

- Literature by and about Marcel Duchamp in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Marcel Duchamp in the German Digital Library

- Search for Marcel Duchamp in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- Marcel Duchamp on kunstaspekte.de with a list of the exhibitions

- Marcel Duchamp - life and work

- Marcel Duchamp in Artcyclopedia (English)

- Art Glossary Marcel Duchamp ( Memento from March 27, 2004 in the Internet Archive )

- Replayable chess games by Marcel Duchamp on chessgames.com (English)

- Making Sense of Marcel Duchamp (English)

- Tout-Fait: Marcel Duchamp Studies Online journal (English)

- Marcel Duchamp World Community (English)

- Leslie Camhi: Did Duchamp Deceive Us? artscienceresearchlab.org (English)

- Materials by and about Marcel Duchamp in the documenta archive

- Duchamp Research Center State Museum Schwerin

- Marcel Duchamp at Google Arts & Culture

Illustrations

- ^ Julian Wasser: Marcel Duchamp and Eve Babitz, Pasadena Museum of Art, 1963. Retrieved August 10, 2010 .

- ↑ Marcel Duchamp: The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Green Box), 1934. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed August 15, 2010 .

- ↑ The Blind Man 2, New York, May 1917, pp. 2-3. Retrieved August 14, 2010 .

- ↑ Duchamp in his studio, playing chess, 1952. Retrieved June 6, 2011 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography . Hanser, Munich 1999, p. 29 ff.

- ↑ Marcel Duchamp's biography ( memento of March 27, 2004 in the Internet Archive ), g.26.ch, accessed on September 25, 2012

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography , pp. 42-47

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography , pp. 51-72

- ↑ a b c d e Arturo Schwarz: Marcel Duchamp biography ( Memento from March 27, 2004 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Marcel Duchamp in Munich 1912, exhibition in the Lenbachhaus Munich, 2012; on-line

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography , p. 114 ff.

- ↑ Uwe M. Schneede: The history of art in the 20th century , p. 52

- ^ Serge Stauffer: Marcel Duchamp. Interviews and statements . Collected, translated and annotated by Serge Stauffer. Edited by Ulrike Gauss . State Gallery of Stuttgart graphic collection. Edition Cantz, Ostfildern-Ruit 1992, p. 38.

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography , pp. 137 ff, 147

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography. Pp. 100 f., 540

- ↑ Marcel Duchamp biography

- ↑ Luigi Carluccio: the sacret and profane art in Symbolist , Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, 1 November to 26 November 1969, p 99

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography , p. 142 f.

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography , pp. 171-182

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography , p. 179

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography , p. 237 f.

- ↑ Thomas Krens (foreword): Rendezvous. Masterpieces from the Center Georges Pompidou and the Guggenheim Museums . Editions du Center Pompidou, Paris 1998, p. 627

- ↑ artic.edu , accessed September 20, 2010

- ^ Hulten, Pontus: Marcel Duchamp. Work and Life: Ephemerides on and about Marcel Duchamp and Rrose Selavy, 1887–1968 . Pages 8-9, June 1927 to January 25, 1928, ISBN 0-262-08225-X

- ↑ Johannes Jahn , Wolfgang Haubenreißer: Dictionary of Art (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 165). 10th, revised and expanded edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 3-520-16510-4 , p. 183.

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography , pp. 142 f., 520

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography , p. 363 f.

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography , p. 367 f.

- ^ Marcel Duchamp, notes to Julien Levy, January / March 1939, Julien Levy Gallery Records, University of Pennsylvania.

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. Eine Biographie , pp. 382-388, 399-408

- ↑ Photo of a showroom toutfait.com

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography , p. 410, 437 ff.

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography , pp. 444, 450, 456

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography , p. 489 f.

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography , p. 512

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography , p. 521 f.

- ↑ Retina (retina of the eye; "retinal" is an art that appeals to the eye)

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography , pp. 50 f., 148 ff.

- ↑ a b Matthias Bunge: From ready-made to "fat corner". Beuys and Duchamp - a productive conflict. In: Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt (ed.): Joseph Beuys. Connections in the 20th Century , Darmstadt 2001, ISBN 3-926527-62-5 , p. 22

- ^ Marcel Duchamp: Notes and Projects for The Large Glass . Ed .: A. Schwarz. Thames & Hudson, London 1969, pp. 209 (note 140).

- ^ Harald Szeemann: Bachelor machines : Junggesellenmaschinen / Les machines Célibataires . Ed .: Jean Clair, Harald Szeemann. Alfieri, Venezia 1975, p. 5.1 .

- ^ Finding Aids , accessed September 18, 2013

- ^ Matthias Bunge: From the ready-made to the "fat corner". Beuys and Duchamp - a productive conflict. In: Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt (ed.): Joseph Beuys. Connections in the 20th Century , p. 26

- ↑ Chess Ambassador III: Marcel Duchamp. Chess Club König Plauen e. V., accessed on August 14, 2010 .

- ↑ Kuh, 1962, pp. 81 and 83, quoted from Serge Stauffer: Marcel Duchamp: Ready Made , Zurich, Regenbogen, 1973, p. 63

- ^ Stephan E. Hauser in: Transform. BildObjektSkulptur im 20. Jahrhundert , Kunstmuseum und Kunsthalle Basel, June 14 to September 27, 1992, Pro Litteris, Zurich 1992, p. 62

- ^ Robert Hughes: The shock of the new . Alfred A. Knopf, New York 1981, p. 66, ISBN 0-394-51378-9

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Müller: The fragrance of the century . In: Welt am Sonntag , January 23, 2011

- ^ O. Hahn: Passeport No G 255 300 . In: ART + Artistes , July 4, 1966, pp. 7-11

- ↑ Sandro Bocola : The Art of Modernism. On the structure and dynamics of their development. From Goya to Beuys. Prestel, Munich / New York 1994, ISBN 3-7913-1889-6 , new edition in Psychosozial-Verlag, Gießen / Lahn 2013, ISBN 978-3-8379-2215-8 , pp. 284 f.

- ↑ Rhonda Roland Shearer : Marcel Duchamp's Impossible Bed and Other 'Not' Readymade Objects: A Possible Route of Influence From Art to Science , Part 1, in: Art & Academe 10, 1, Fall 1997, pp. 26-62

- ↑ Marco de Marting: Mona Lisa: Who is Hidden Behind the Woman with the Mustache? ( Memento of March 20, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Retrieved November 4, 2010

- ↑ Christiane Ladleif in: Open box. Artistic and Scientific Reflections on the Concept of Museum , ed. by Michael Fehr, Wienand, Cologne 1998, p. 130

- ↑ Boîte-en-valise moma.org

- ^ Philadelphia Museum of Art

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography , p. 523

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography , pp. 416, 426 f.

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography , p. 536

- ↑ Marcel Duchamp's results at unofficial chess Olympiads on olimpbase.org (English)

- ↑ Marcel Duchamp's results at the Chess Olympiads on olimpbase.org (English)

- ↑ Marcel Duchamp, Vitali Halberstadt: L'opposition et les cases conjuguées sont réconciliées , Paris 1932; German: Opposition and sister fields , 2001, ISBN 3-932170-35-0 .

- ↑ Michael Ehn , Hugo Kastner : Everything about chess. Humboldt, Hannover 2010, p. 8, ISBN 978-3-86910-171-2 .

- ^ The Unholy Trinity ( Memento of May 4, 2008 in the Internet Archive ), accessed September 25, 2012

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography , p. 315

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography , p. 410

- ↑ arte.tv, October 12, 2005 ( memento of February 22, 2010 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on September 18, 2010

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography , p. 498

- ↑ Götz Adriani , Winfried Konnertz and Karin Thomas: Joseph Beuys . DuMont; New edition, Cologne 1994, ISBN 3-7701-3321-8

- ↑ Uwe M. Schneede: Joseph Beuys. The actions . Annotated catalog raisonné with photographic documentation. Verlag Gerd Hatje, Ostfildern-Ruit, 1994, p. 80 f.

- ↑ Uwe M. Schneede: Joseph Beuys. The actions . Ostfildern-Ruit, 1994, p. 80 f.

- ^ Biography Richard Hamilton ( Memento from October 16, 2005 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Merce Cunningham Dance Company. Video with interviews and contemporary film recordings

- ↑ Valentina Vlasic : Saâdane Afif. In: The Present Order is the Disorder of the Future , Series of publications Museum Kurhaus Kleve - Ewald Mataré Collection No. 62, Freundeskreis Museum Kurhaus and Koekkoek-Haus Kleve e. V. (Ed.), July 14 to September 15, 2013, p. 47

- ^ Duchamp research grant , hsozkult.geschichte.hu-berlin.de, accessed on September 17, 2013

- ↑ fatrazie.com: Histoire de Collège - Le 22. palotin 80 (French, accessed on July 30, 2014)

- ↑ Members: Marcel Duchamp. American Academy of Arts and Letters, accessed February 27, 2019 .

- ↑ Duchamp's urinal tops art survey , news.bbc.co.uk, December 1, 2004, accessed February 7, 2012

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Duchamp, Marcel |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Sélavy, Rose (pseudonym); Sélavy, Rrose (pseudonym); Mutt, R. (pseudonym) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French-American painter and object artist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 28, 1887 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Blainville-Crevon |

| DATE OF DEATH | 2nd October 1968 |

| Place of death | Neuilly-sur-Seine |