Joseph Beuys

Joseph Heinrich Beuys [ bɔɪ̯s ] (born May 12, 1921 in Krefeld , † January 23, 1986 in Düsseldorf ) was a German action artist , sculptor , medalist , draftsman , art theorist and professor at the Düsseldorf Art Academy .

In his extensive work Beuys dealt with questions of humanism , social philosophy and anthroposophy . This led to his specific definition of an “ expanded concept of art ” and to the conception of social sculpture as a total work of art , in that at the end of the 1970s he called for creative participation in society and in politics . He is regarded worldwide as one of the most important action artists of the 20th century and, according to his biographer Reinhard Ermen, is to be seen as the "ideal typical opponent" of Andy Warhol .

Life

Childhood and Adolescence (1921–1941)

Joseph Beuys, who grew up in Cattle , a small village north of the New Tiergarten in Kleve , was the son of the businessman and fertilizer trader Josef Jakob Beuys (born March 8, 1888 in Geldern ; † May 15, 1958 in Kleve ) and his wife Johanna Maria Margarete Beuys (née Hülsermann, born July 17, 1889 in Spellen ; † August 30, 1974 there). The father, who belonged to a miller and flour merchant's family of funds was in 1910 as clerk of funds to Krefeld drawn where the parents lived after marrying at Alexanderplatz. 5 In the autumn of 1921 the family moved to Kleve and first registered at the address Kermisdahlstraße 24, in the immediate vicinity of Schwanenburg . After two more moves, with a registration date of May 1st, she moved to the upper floor of the house at Tiergartenstrasse 187 / the corner of Stiller Winkel (today house number 101) in Neu-Cattle, a new housing estate at that time a few hundred meters west of the former Kurhaus Kleve .

From 1927 to 1932 Joseph Beuys attended the Catholic elementary school, then the state high school in Cleve, today Freiherr-vom-Stein-Gymnasium . He learned to play the piano and cello; at school he showed talent in drawing lessons. Outside of school he visited the studio of the Kleve-based Flemish painter and sculptor Achilles Moortgat , who introduced him to the work of Constantin Meunier and George Minne . Beuys was also impressed by the works of Edvard Munch , William Turner and Auguste Rodin . The pupil's interests, aroused by a teacher, were in Norse history and mythology . In addition, he developed an interest in science and technology and at times contemplated becoming a pediatrician . During the book burning organized by the National Socialists in Kleve on May 19, 1933 in the courtyard of the grammar school, he said he had "put aside the book Systema Naturae by Carl von Linné from this big burning heap [...]."

By 1936 at the latest, the 15-year-old Beuys was a member of the Hitler Youth when he took part in the Reich-wide big star march to the Nazi party rally in Nuremberg in HJ-Bann 238 / Altkreis Kleve . In the last years of school - in 1938 he had seen a catalog with reproductions of Wilhelm Lehmbruck's sculptures for the first time - Beuys decided to become a sculptor. From 1938 he played the cello in the so-called "ban orchestra" of the Hitler Youth. Around 1939 Beuys joined a circus in order to work as a poster carrier and zoo keeper for almost a year. According to the majority of his biographies, he left the grammar school with a certificate of maturity at Easter 1941 , but according to Hans Peter Riegel in the spring of 1940 without a qualification.

Wartime (1941–1945)

In the spring of 1941 Beuys volunteered for the Air Force , where he committed himself for twelve years. From May 1, 1941, he was trained as a radio operator in Posen by the later animal and documentary filmmaker Heinz Sielmann . Sielmann encouraged his recruit's interest in botany and zoology . Beuys attended lectures in these subjects and geography at the University of Posen for seven months as a guest auditor .

After completing his training as a radio operator, he was stationed in the Crimea and took part in the air battle for the fortress city of Sevastopol in June 1942 . From May 1943, Beuys was now a sergeant, he was deployed in Königgrätz in what was then the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia as a gunner and radio operator in a Ju 87 dive fighter plane (Stuka) . After being transferred to the Croatian Air Force Staff in the summer of 1943, he was stationed on the eastern Adriatic until around 1944 . From there he flew temporarily to the air force base in Foggia for weapons tests . Numerous sketches and drawings from the days of the war were made here.

Plane crash in Crimea

On March 4, 1944, the Red Army began its spring offensive on the Eastern Front and forced the complete withdrawal of German units from Ukraine in the Battle of Crimea . During a mission in which snowfall caused poor visibility, Beuys' Stuka had contact with the ground while flying blind on March 16, 1944, 200 meters east of Freifeld , and crashed into the ground. The pilot Hans Laurinck died, Beuys was injured. He suffered a nasal bone fracture , several broken bones and a crash trauma . He was found by a German search team among the rubble of the Ju 87 and taken to the mobile military hospital 179 in Kurman-Kemeltschi on March 17, 1944 , which he was only able to leave on April 7, 1944.

The crash and its aftermath served Beuys as the material of a legend, according to which nomadic Crimean Tatars cared for him “sacrificially for eight days with their home remedies” (anointing the wounds with animal fat and keeping them warm in felt). This legend, which was supposed to explain Beuys' preference for the materials fat and felt and which Beuys also described in a BBC interview, was also represented by his biographer Heiner Stachelhaus to the end. According to research by the artist Jörg Herold , Beuys was found by a search team soon after the crash, as the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung reported in a report dated August 7, 2000 about Herold's search for clues in the Crimea. The eight to twelve-day stay with the Tatars, as reported by Stachelhaus and others, was already questioned in 1996 by Beuys' own wife Eva. The widow classified the story, told again and again by her husband, as "feverish dreams in long unconsciousness".

End of war

In August 1944, Beuys was sent to the Western Front , where he served as a senior hunter in the Erdmann paratrooper division . He received the wound badge . One day after the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht on May 8, 1945, Beuys was taken prisoner by the British in Cuxhaven and was taken to a camp, which he was allowed to leave on August 5, 1945. Physically badly damaged, he returned to his parents in Neu-Cattle near Kleve.

Studies and departure (1945–1960)

In 1945 he joined the artist group of the Kleve- based painter Hanns Lamers . In 1946, at the age of 25, he became a member of the “Klever Künstlerbund” (formerly “Profil”), newly established by Lamers and Walther Brüx . From 1948 to 1950, Beuys took part three times with drawings and watercolors in the association's group exhibitions, which took place in Barend Cornelis Koekkoek's former studio house , now the BC Koekkoek House .

In the summer semester of 1946 Beuys enrolled at the State Art Academy in Düsseldorf . He began studying monumental sculpture on April 1, 1946. During his first semester with Joseph Enseling , with which he studied for three semesters, he met Erwin Heerich , Holger Runge and Elmar Hillebrand . From the winter semester of 1947/1948, Joseph Beuys switched to Ewald Mataré's class at the instigation of Heerich . From 1947 to 1949 he worked at the zoological films by Heinz Sielmann and Georg Schimanski over the life rhythm of the game in the birch forest of the Lüneburg Heath , over northern wild swans, geese and ducks in the alluvium of the Ems and on the life of the white stork in Schleswig-Holstein Bergenhusen with . In 1948 he came into contact with the esoteric teachings of Rudolf Steiner in a working group headed by the anthroposophist Max Benirschke .

The master student

Ewald Mataré appointed Joseph Beuys as his master student in 1951 . Together with Erwin Heerich, Beuys moved into his master class studio under the umbrella of the art academy until 1954.

He worked on orders from his teacher Mataré, for example on the doors for the south portal of Cologne Cathedral , the so-called "Pentecost Door", where he set the mosaic, and on the west window in the westwork of Aachen Cathedral . It was during this time that - presumably as a task for Mataré - he created his early plastic torso , a woman's torso floating on an extended sculptor's trestle and covered with black oil paint and gauze bandages. Together with Heerich, Beuys worked on a copy of the sculpture Mourning Parents by Käthe Kollwitz in Muschelkalk. Mataré, who received this commission for a memorial in Alt St. Alban in 1953 , passed it on to his two master students, with Heerich making the mother and Beuys the father.

A central topic in the Matarés class was the discussion about Rudolf Steiner . According to the memory of a fellow student, seven of the initial nine students are said to have been enthusiastic about Steiner's anthroposophy . Steiner's writing, key points of the social question , proved to be a formative influence on Beuys ; for him it became a key text for his later ideas on social sculpture . Mataré himself orientated himself on the old building hut ideals and did not believe in Steiner's teaching. According to Günter Grass , who studied with Otto Pankok at the same time as Beuys, the student Beuys had a dominant position in the Matarés class, which, under Beuys' influence, was “Christian to anthroposophical.” Grass described the mood among the students at the academy for sixty years later like this: "Everywhere geniuses seemed to be on the rise [...]"; these “geniuses” were mostly epigones for Grass .

First exhibitions and commissions

During his time as a master student, Beuys' first solo exhibition took place in 1953 in the house of the brothers Hans and Franz Joseph van der Grinten in Kranenburg (Lower Rhine) and an exhibition in the Von der Heydt Museum in Wuppertal . He finished his studies after the winter semester of 1952/1953 on March 31, at the age of 32. In 1954 Beuys moved into his own studio in Düsseldorf- Heerdt , which he was able to use until the end of 1958. From 1951 to 1958, the artist lived from various, more manual jobs. In 1951 he made a tombstone for Fritz Niehaus, Ruth Niehaus's father, which is now in the cemetery in Meerbusch -Büderich . He also designed furniture, some of which he sold. Two tables, titled Chest , 1953 ( ebony ), and Tête , 1953–1954 ( pear tree , ebony), and a shelf from 1953 titled Royal Pidge-Pine are in a private collection in Athens ; Another table, Monk , 1953 (pear tree, ebony) is now in the Beuys block , Darmstadt.

Beuys, who found himself in a phase of upheaval in artistic work as a “reaction to the circle of friends' lack of willingness to communicate when reassuring their own concerns”, increasingly withdrew from 1955 after his fiancée had sent him the engagement ring at Christmas 1954; he suffered from melancholy and listlessness. In 1957 he stayed for a few months on the van der Grinten family farm in Kranenburg. In addition to the field work , which lasted from April to August, he drew and designed concepts for sculptures. He had intensive conversations with the van der Grinten brothers about Konrad Lorenz , whom he had met in 1954/1955 through Sielmann in the Westphalian Wasserburg of the von Romberg family in Buldern ; At that time Lorenz was head of the research department of the Max Planck Institute for Behavioral Physiology in the marine biology department at the moated castle. Discussions were also held about his joint film work with Heinz Sielmann, about works by Rudolf Pannwitz and Joséphin Péladan and art. From 1956 the artist worked on the design for an “Auschwitz Memorial”, and in the following year he took part in an international competition for a memorial in the former Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp , for which 426 artists submitted designs. The draft was rejected.

At the end of 1957 Beuys moved to Kleve because his father was in the hospital there; he died on May 15 of the following year. Beuys rented his own studio space in the old Kurhaus am Tiergarten, in which the monumental oak cross and the gate for the Büderich memorial for the dead of the world wars in the old church tower in Meerbusch-Büderich were built in 1959 . It is the largest public contract that Joseph Beuys carried out at the time, against the objections of Ewald Mataré. On May 16, 1959, the “Büderich Memorial” was handed over. In the same year Beuys began to draw stapled business books in four three hundred pages each (until 1965). In 1958 he first used fat and felt, which are unusual for art . In parallel to his artistic work, Beuys continued to pursue scientific , in particular zoological, studies.

On September 19, 1959, Joseph Beuys married Eva-Maria Wurmbach, whom he had met a year earlier, in the twin church Schwarzrheindorf . The daughter of the zoologist Hermann Wurmbach and his wife Maria Wurmbach (née Küchenhoff) studied art education at the Düsseldorf Art Academy . The two children Boien Wenzel, born on December 22, 1961, and Jessyka, born on November 10, 1964, emerged from the marriage. He developed a close working and trusting relationship with his private secretary Heiner Bastian from 1968.

University and the public (1960–1975)

In March 1961, Joseph Beuys moved to Düsseldorf- Oberkassel while keeping his Klever studio at the Tiergarten and moved into a studio brokered by Gotthard Graubner in the house of Georg Pehle, son of the sculptor Albert Pehle and nephew of Walter Ophey , at Oberkassler Drakeplatz 4, where he lived and worked until his death. In 1980 he moved into a residential building at 74 Wildenbruchstrasse with access via a gate and a forecourt and adjacent former garage building, which he used as a second studio until his death in 1986.

In 1950, based on a design by Ewald Mataré, Beuys made a standing grave slab, a slate in the shape of a large bird, for Ophey and his son Ulrich Nikolaus, who died prematurely. Today's grave slab, which in its original state in 1950 still bore a cross in the lower part, was supplemented by the names of Ophey's wife Bernhardine Bornemann (1879–1968) and Georg and Luise Pehle by 1978. Like a grave cross from 1970 created for the late Karl Wiedehage, former chief physician at Dominikus Hospital in Düsseldorf- Heerdt , it is in the Heerdter cemetery . Wiedehage had to remove a kidney in the early 1960s after he fell while cleaning the stove pipe in his Klever studio, which Beuys used until 1964, and fell with his back on the edge of the coal stove.

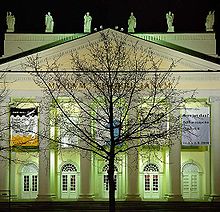

Beuys had already applied for a professorship at the Düsseldorf Art Academy in 1958 , which met resistance from his teacher Mataré. Three years later, in 1961, he was appointed to the “Chair for Monumental Sculpture at the State Art Academy in Düsseldorf” as the successor to Josef (Sepp) Mages , who had held the position at the Academy since 1938, with the unanimous decision of the Academy Board November 1961. He was considered a reliable, rather strict teacher who soon made a name for himself with sensational actions that had nothing to do with classical sculpture. In February 1963, for example, he staged the FESTUM FLUXORUM FLUXUS in the auditorium of the academy, which was scheduled for two Fluxus evenings and where he carried out his first actions.

The teacher

Inwardly, Joseph Beuys had long since abandoned the usual artistic interpretation of this subject area. Büderich's memorial from 1959 marked the end of his conventional sculptural phase. The search for a comprehensive concept of art for all people was behind his expanded art trade, which became increasingly apparent in the following years. With his development of a social “ expanded concept of art ”, Beuys attempted to change the structure of the current educational, legal and economic terms.

In the years up to 1975, Beuys not only looked after an unusually large number of students, he also managed to successfully prepare a large number of very different artistic personalities for their own artistic practice. These include not only the “border crossers” between performance and installation, such as Felix Droese and Katharina Sieverding , but also a number of distinguished painters with Jörg Immendorff , Axel Kasseböhmer and Blinky Palermo . His youngest student was Elias Maria Reti, who was already studying art in his class at the Düsseldorf Art Academy at the age of 15.

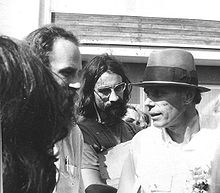

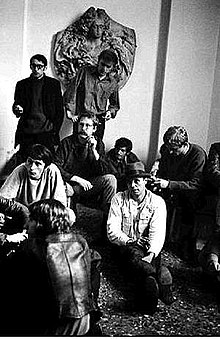

Joseph Beuys was present at the academy almost every day, even on Saturdays and during the semester break. From 1966 he regularly organized so-called ring discussions with his students, initiated by Anatol Herzfeld , in which theories were drafted and discussed every two weeks. These discussions were public and took place until Beuys' resignation without notice (see below) by his employer, the Ministry of Science, in 1972. The turn to theory was initially quite controversial among the first generation of students. He took part in the student exhibitions, the annual tours at the end of the winter semester in February.

Beuys was also of the opinion that anyone wishing to study art should not be prevented from doing so by admission procedures such as a portfolio procedure (the applicant had to provide evidence of their talent in the form of work) or a numerus clausus . He informed his colleagues that he would accept all applicants for a university place who had been rejected by other teachers in his class. In mid-July 1971, 142 out of 232 applicants for teacher training were rejected in the normal admission procedure. On August 5, 1971, Beuys read a public letter to the press that he had sent to the academy director on August 2. All 142 rejected students had been accepted into his class by Beuys; he had about 400 students in the following semester. On August 6th, the Ministry of Science explained to the press that it did not approve this admission of study applicants and that applicants were offered to study at another academy.

On October 15, 1971, Beuys and seventeen students from his group occupied the academy's secretariat. In a conversation with the Minister of Science Johannes Rau , he managed to get the Academy of Arts to accept these applicants with the recommendation of the Ministry of Science. On October 21, the Ministry of Science informed Beuys in writing that such situations would no longer be tolerated, but Beuys did not take this warning seriously.

The discharge

At the end of January 1972, a conference on a new admission procedure took place at the art academy, in which Beuys himself took part. The size of a class was limited to 30 students. In the summer, 227 applicants were accepted and 125 rejected. 1052 students were enrolled at the Düsseldorf Art Academy, 268 of them in the Beuys class.

When Beuys again occupied the secretariat of the Düsseldorf Art Academy with rejected students in 1972, Minister Rau dismissed him without notice. Accompanied by police officers, Beuys had to leave the academy with his students. On October 11, 1972, Johannes Rau gave a press conference on the Beuys case and called the dismissal “the last link in a chain of constant confrontations.” In the days that followed, the students of the academy reacted with hunger strikes, a three-day boycott of lectures, signature campaigns, and banners (“1000 Out does not replace a Beuys ”) and information walls about the events. The Ministry of Science received numerous letters of protest and telegrams from all over the world. The response from radio, television and the press was great. In an open letter , artist colleagues, including the writers Heinrich Böll , Peter Handke , Uwe Johnson , Martin Walser , as well as the artists Jim Dine , David Hockney , Gerhard Richter and Günther Uecker , demanded the reinstatement of one of the most important artists of the German post-war period. On October 20, 1973, about a year after his release, Beuys crossed the Rhine in a dugout canoe built by his master student Anatol Herzfeld from the bank of the Oberkassel district to the opposite bank, where the art academy is located. This “ bringing home Joseph Beuys ” as a spectacular symbolic act aroused great public interest. In 1974 Beuys received a visiting professorship in the winter semester at the University of Fine Arts in Hamburg .

Beuys initiated a lawsuit that lasted for years with a lawsuit against the state of North Rhine-Westphalia . In 1980 a settlement was reached before the Federal Labor Court in Kassel : Beuys was allowed to keep his studio in "Room 3" in the academy until he was 65 and to continue to hold the title of professor, but he accepted the termination of the employment relationship. On November 1, 1980, Beuys opened the Free International University (FIU) office in his “Raum 3” studio . It was dissolved after Beuys' death.

Documenta and commercial success

After Beuys took part in documenta III in Kassel in 1964, at which he was regularly represented with his works from then on, individual presentations and his increasing public presence followed. With the action how to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare Joseph Beuys opened in November 1965 in that of Alfred Schmela led Schmela Gallery , Dusseldorf, the solo exhibition "... any train ...", his first exhibition in a commercial gallery. The municipal museum in Mönchengladbach showed the first comprehensive exhibition BEUYS from September to October 1967 . By contractual agreement, the exhibited works passed into the possession of the collector Karl Ströher , provided that the essential part of the work “remains closed and is made accessible to the public”. During one of the “tours” in February 1969 at the Düsseldorf Art Academy, Beuys exhibited his own work, Revolution Clavier, an instrument covered with around 200 red carnations and roses. The Kupferstichkabinett at the Kunstmuseum Basel showed the exhibition Joseph Beuys Drawings, Small Objects from July to August 1969 .

His gallery owner René Block achieved a decisive breakthrough on the art market at the Cologne art market in 1969: For Beuys' installation The pack , an old VW bus with 24 sled objects, he achieved DM 110,000; the amount was the same as that paid for a large painting by Robert Rauschenberg .

On the occasion of the opening of an exhibition by André Masson in the Museum am Ostwall in Dortmund , a conversation between Joseph Beuys and Willy Brandt took place in April 1970 . Beuys suggested making television available to artists at least once a month as a discussion forum so that the general public could get to know the ideas of the true opposition . The point was that this opposition would get effective opportunities to be able to specify their socio-political ideas, because, according to the artist, they have “no other level of information than the street,” and therefore he asks, not for himself, “for a corresponding liberation of the Media. ”Brandt made sense, but said he could not advocate that art“ by virtue of a political office somehow become […] propaganda ”. A two-day working conference between Joseph Beuys, Erwin Heerich and Klaus Staeck took place in Heidelberg in September 1971 . The aim was to develop a concept for the organization of an “international free art market”. As a result, in October 1971 a “2nd international meeting of the free art market ” takes place in the Kunsthalle Düsseldorf .

To documenta 5 in 1972 Beuys' work was Dürer, I lead personally Baader Meinhof + by the Documenta V , under the aspect of an artistic consideration of the incipient terror of the Baader-Meinhof group was created. In June 1972, on the opening day of the Arena exhibition , at which Beuys arranged 264 photo documents of his autobiographical impact in the form of an arena, the Vitex Agnus Castus action took place at Lucio Amelio's in the Modern Art Agency in Naples . The exhibition was opened a few months later under the title Arena - dove sarei arrivato se fossi stato intelligent! (German: Arena - where would I have gone if I had been intelligent!) shown in the Galleria l'Attico in Rome , where the artist performed the spontaneous action Anacharsis Cloots . It was named after the personality he admired and used as his alter ego , Anacharsis Cloots , who spent his youth at Schloss Gnadenthal and later called himself the "speaker of the human race". Beuys, who at times identified himself with Cloots as "Josephanacharsis Clootsbeuys", recited excerpts from a biography published in 1865 by Carl Richter of this revolutionary of the 18th century who died under the guillotine in France in 1794.

International presence and awards (1975–1986)

In January 1974 Beuys traveled to the USA for the first time . The gallery owner Ronald Feldman, New York , had organized a ten-day lecture tour through the United States for him under the title Energy Plan for the Western Man . In front of numerous listeners in the art colleges of New York, Chicago and Minneapolis , he spoke, among other things, about the "whole question of the possibility that everyone should now do their own special kind of art, their own work, for the new social organization".

At the 37th Venice Biennale in 1976 Beuys was represented in the German pavilion with the installation Tram Stop / Tram Stop / Fermata del Tram , 1961–1976. On March 16, 1977, Beuys installed the work Richtkraft - 100 Tafeln in the Nationalgalerie Berlin , with the words "east" and "west" written on one of the ends of a line and the words "Eurasia" in the middle above a dividing line and “Berlin wall” - the wall as a line separating two different spheres of thought, which Beuys described as “western private capitalism ” and “eastern state capitalism ”. On the same evening there was a public discussion in which Beuys carried a rucksack on his back, an allusion to the wandering shepherd . At documenta 6 1977 Beuys was represented for 100 days with the honey pump in the workplace . At the same time, he created the site-specific work Unschlitt / Tallow (temporary heat sculpture) for the project area of the “Sculpture” exhibition in Münster , which is now part of the Marx Collection in the Hamburger Bahnhof - Museum für Gegenwart in Berlin.

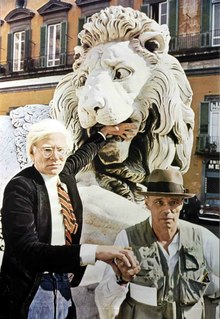

In May 1979 he met Andy Warhol for the first time in the Denise René / Hans Mayer gallery in Düsseldorf , who was showing an exhibition of his new pictures there. At this meeting , Warhol made a Beuys Polaroid , which became the template for several serigraphs processed with diamond dust . Both artists, who were regarded by the art market as two contrary stars, met again in the gallery on November 7, 1979 on the occasion of the opening of the exhibition Art = Capital - Joseph Beuys, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol , to which the magazine Capital had invited Hans Mayer. From November 2, 1979 to January 2, 1980, the Guggenheim Museum in New York dedicated an extensive retrospective to him as the first German. Beuys was 58 years old at the time.

On April 1, 1980, Beuys and Warhol met at the Lucio Amelio gallery in Naples, where Andy Warhol showed his new screen-printed portraits entitled Joseph Beuys in the exhibition Joseph Beuys by Andy Warhol . In April 1981 Beuys stayed in Rome to produce the action sculpture Terremoto in the Palazzo Braschi . In the same month another work was created in Italy, Terremoto in Palazzo , on the occasion of an exhibition in Naples for the benefit of the victims of the devastating earthquake in Naples on November 23, 1980; In 1983 the artist produced a multiple under the same title as a color offset series.

In August 1981 he and his family traveled through Poland in a mobile home to visit the places he had already got to know as a young soldier. In Łódź he donated 800 of his drawings, graphics, posters, texts and manifestos to the Muzeum Sztuki . The first Beuys exhibition in the GDR took place from October to December 1981 . In the Permanent Mission of the Federal Republic of Germany in East Berlin , multiples from the Günter Ulbricht collection, Düsseldorf, were shown.

At documenta 7 in Kassel in 1982, Beuys realized his sculpture Stadtverwaldung instead of Stadtverwaltung (7000 oak trees) . Beuys did not live to see the end of the complex planting campaign. By the time he died, only 5500 oaks, each with a basalt stele, had been planted. His son Wenzel planted the last tree during documenta 8 on June 12, 1987. The tree-stone pairs are still present in the cityscape to this day.

Beuys had the idea of organizing a permanent conference on human issues with the Dalai Lama and starting a cooperation with him. On October 27, 1982 they met for a conversation in Bonn . This meeting was organized by Louwrien Wijers from the Netherlands, who said that Beuys' vision of turning politics into art should interest the Dalai Lama. The conversation, which lasted an hour, has not been published or recorded. All that has been handed down is that Joseph Beuys spoke almost exclusively. He submitted his vision of a "global social sculpture " to the Dalai Lama . He also planned to present an economic plan for Tibet to the Chinese who had occupied Tibet in 1949 .

In autumn 1982 Beuys exhibited an important ensemble of works entitled “Deer Monuments” at the Zeitgeist exhibition in the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin ; Its components have flowed into the environment Blitzschlag with Lichtschein auf Hirsch , which was acquired by the City of Frankfurt am Main in 1987 and is now in the Museum of Modern Art (MMK). In the spring of 1983, the Hamburg cultural authority gave the artist a planning order for the sink areas in Altenwerder , which today serve as a container terminal . Beuys developed a planting concept; the project Gesamtkunstwerk Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg was finally rejected by the Senate of Hamburg in July 1984.

Late years and death

The city of Bolognano made Joseph Beuys an honorary citizen in May 1984 after he had planted the first 400 of 7000 trees and bushes between May 11 and 14 for the establishment of a nature reserve in the community. In the same year, two exhibitions were opened in Tokyo , which the artist, who by now had suffered from health problems, prepared himself. One took place from May 15 to July 17, 1984 in the Watari Gallery: Joseph Beuys & Nam June Paik ; the other with works from the Ulbricht collection followed from June 2 to July 2, 1984 in the Seibu Museum. With the installation Wirtschaftswerte , 1980, Beuys took part in the exhibition From Here - Two Months of New German Art in Düsseldorf , which took place from September to December 1984.

On January 12, 1985, Beuys took part in the “Global Art Fusion” project , together with Andy Warhol and the Japanese artist Kaii Higashiyama . This was an intercontinental FAX-ART project initiated by the concept artist Ueli Fuchser, in which a fax with drawings by all three artists involved was sent around the world within 32 minutes - from Düsseldorf via New York to Tokyo, received at the Palais in Vienna. Liechtenstein . This fax was intended to represent a sign of peace during the Cold War. At the end of May 1985, Joseph Beuys fell ill with interstitial pneumonia . During a convalescent stay in Naples and on Capri in September 1985, the sculpture Scala Libera , 1985, and a prototype of the Capri battery were created . Shortly before his death, on November 20, 1985, the artist gave a keynote speech at the Münchner Kammerspiele with “Speaking about one's own country: Germany” . He once again addressed his theory that “every person is an artist”. The last installation set up by Joseph Beuys, Palazzo Regale , was shown at the Museo di Capodimonte in Naples from December 1985 to May 1986 . In January 1986 he was awarded the prestigious Wilhelm Lehmbruck Prize of the city of Duisburg . Eleven days later, on January 23rd, Joseph Beuys died at the age of 64 in his studio at Drakeplatz 4 in Düsseldorf- Oberkassel after an inflammation of the lung tissue of heart failure. He was buried at sea on April 14, 1986 . The German motor ship Sueño (German: "Dream") with home port Meldorf sailed to position 54 ° 7 '5 " N , 8 ° 22' 0" E , where its ashes were handed over to the North Sea.

Person Beuys

The daily presence at the academy, the willingness to provide information to the press, radio and television and the ruthlessness with which Beuys seemed to present himself in his art actions up to the overexploitation of health shaped the image of the artist.

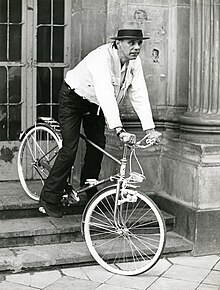

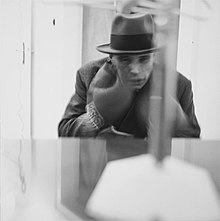

At the academies in the 1960s it was by no means customary for the teacher to be available to the students on a daily basis and to try to combine their own artistic work with the training of the students; later this remained the exception. Exhibitions usually found little response in the daily press; contemporary art had its specialist circles and its limited gallery audience. Catalogs did not show photos of the artists. The art actions of the 1960s allowed the press and television to see interesting black and white images for the first time; the actions of Joseph Beuys, in their forms, which at the time were perceived as unusual or even annoying, gave rise to the person of the artist in the picture. After the spectacular crossing of the Rhine in 1973, the artist's clothing, which in itself attracted little attention and consisted of jeans, a white shirt with a fishing vest and a felt hat, became a trademark that Beuys continued not only for the media dissemination of his ideas, but also for his appearance after 1980 set in on the political stage.

The artist's work, which is difficult to depict, has been replaced by the image of the “man in the felt hat”. The polarizing effect of the work carried over to the perception of the person. The critics disrespectfully spoke of a " charlatan " or " shaman ", enthusiastic followers considered him a " Leonardo da Vinci of the present". The abundance of statements that Beuys communicated to the public also gave sufficient cause for attributions to his person. For his reflections on a central motif in art, for example, death, he was called a “man of pain in art”.

"In truth, he always did the other thing, always that which was seemingly absurd - talking 100 days at the documenta, wrapping himself in felt, standing on a spot for hours, living with a coyote, washing people's feet, taking gelatine off the wall, Sweep the forest, explain the pictures to the dead hare, found a party of animals and bandage the knife when he cut his finger. "

plant

The extensive work of Joseph Beuys essentially comprises four areas: material work in the traditional artistic sense (painting and drawings, objects and installations), the actions, the art theory with teaching and his socio-political activities.

CV-work history

From 1961 onwards, Beuys began to draw up a kind of “poetry and truth” for his artist vita in a literary and artistic form with his curriculum vitae , which included experiences and memories from childhood, adolescence and the military . This self-portrayal was also conceived as a contrast to the artists' lives expected from galleries and museums. Beuys turned his biography into a work of art himself and “drew” a parallel between his life and his art.

Drawings and scores

Drawings and scores

External web links

- Fe, 1951 ( Memento of November 9, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- untitled, 1958 ( Memento from November 9, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- Minneapolis Fragment, 1977

The graphic work contains its own imagery and led from the early study of nature to the late handwritten board diagrams, which he included in his actions, installations and discussions. Initially, his drawings mostly had a filigree style, sometimes the drawings resembled simplified studies. He liked to make them on materials found every day.

In the early 1940s and 1950s he created numerous drawings that can be associated with objects or sculptural works, with Beuys mostly using mixed techniques of watercolor and pencil. Among them are female nudes sketched with delicate lines and animal studies of mostly rabbit or deer-like creatures. In later works he dealt with phenomena of epistemology and energetic or morphological transformation, which were followed by drafts of new social structures.

Beuys understood the works on paper created after 1964 as so-called “scores”. They were closely related to the actions carried out in the 1960s and early 1970s, had a more functional character and are "in the sense of visual art practice to be understood as preparatory work for the actual work." Character of the score . On the one hand, the musical and rhythmic aspect of these drawings can be heard in them; on the other hand, they give an indication of the props that he used in his actions. The "diagrams" of the 1970s document an ever more intense debate about the idea of a social sculpture and sometimes have "the character of protocols of his educational efforts." They create structural references that show that Beuys' work is not just dialogue with the signs and the image culture, but also an examination of philosophy, literature, the natural and social sciences. It "both the phenomena of nature and inner images and ideas motivated him to draw: ideas of German idealism, early romanticism, the Enlightenment, the philosophy of the 19th and 20th centuries."

Fluxus and action art

Fluxus and action art

External web links

Fluxus , action art and happenings were primarily works of art from the late 1950s, which reached their peak in the 1960s. In Fluxus, European and American artists worked together in a joint movement for the first time.

After Beuys at the vernissage of the exhibition ZERO. Edition, exposition, demonstration in the Schmela Gallery on Nam June Paik and a year later on George Maciunas , he carried out around thirty large actions. It all started in 1962 when he developed ideas for an earth piano . Most of these actions were carried out by Joseph Beuys in the 1960s, around 1963 the Siberian Symphony 1st movement and the composition for two musicians at the Festum Fluxorum Fluxus . Presenting to an audience a process that had been devised by oneself and carried out with one's own person and body had already been anticipated by the Futurists , the Dadaists and the Happenings . Beuys' actions are considered to be the core of his work , as he covered them with a plastic theory by using materials such as fat or felt to the "warmth" and "cold", which he recognized as "basic polar principles" Beuys has obtained from the United Filzfabriken AG in Giengen an der Brenz since the 1960s . The use of one's own person shows, in addition to sound and acoustic signals, the intention to open up a conventional concept of art to an “extended art” that reflects the “unity of genres”. The special aspect of "movement" illustrates a "nomadic habitus" (Beuys) and thus a principle of life and work for the artist.

First flux promotions

The first Fluxus actions by Beuys initially received little attention from the general public, but the artist managed to achieve international renown in a short time with his controversial actions and installations, and soon ranked first on the German art scene. In contrast to the Happening, Beuys did not involve his audience directly, but knew how to incorporate audience reactions into his performances: During an action at the “Festival of New Art” in Aachen on July 20, 1964, an angry student hit his nose bloodily . Although the blood flowed down his head, he spontaneously included the attack in the action and grabbed a crucifix to "demonstratively hold it in front of the indignant audience." A photo of this action by Heinrich Riebesehl soon circulated in the German press.

Actions with symbolic character

During the 24-hour happening in June 1965 in the Wuppertal gallery Parnass of the gallery owner Rolf Jahresling , he brought honey, fat, felt and copper in his action and in us ... among us ... by using the materials originally belonging to Arte Povera symbolic “thing vocabulary” artistically to visualize, which he substantiated in this action with the meanings “energy storage”, “tension” and “creativity”. Further actions with titles such as How to explain the pictures to the dead rabbit , 1965, Infiltration Homogen für Konzertflügel , 1966, EURASIA , 1966, Manresa , 1966, and Titus Andronicus / Iphigenie , 1969, followed. In 1974, he spent three days with a coyote, worshiped as sacred by North American natives, in the rooms of René Block's New York gallery in the I like America and America likes Me campaign . In particular, the action with the coyote, documented in numerous photographs, contributed a lot to Beuys' nimbus of the “ shaman ”, as the artist offered the media-effective image of a “holy man” who practices an enigmatic, animistic liturgy. In this respect, Beuys' art also had a meaning for the areas of the soul that are susceptible to myths, magic, rites and shamanistic magic. Beuys rejected the interpretation of his works as well as the self-interpretation as "inartistic". “Even if the work of art is the greatest puzzle, the human being is the solution,” he said and left it at that.

The artist always planned his actions meticulously: he made numerous scores beforehand and wrote down his ideas; Despite all his spontaneity, he did not leave anything to chance, which becomes clear in the film document EURASIENSTAB (Antwerp 1968): The viewer often sees Beuys looking at his wristwatch in order to coordinate his actions precisely with the organ music of the participating composer Henning Christiansen .

With Christiansen, Beuys also performed Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) Scottish Symphony from August 26th to 30th, 1970 in Edinburgh . The performance was part of the Festival Strategy: Get Arts (Contemporary Art from Düsseldorf, presented at Edinburgh College of Art by the RDG in association with Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, for the Edinburgh International Festival.)

With the planning and implementation of the Kassel city deforestation campaign 7000 Eichen , Beuys realized social art in the form of a landscape work of art in which life, art, politics and society form a unity. In order to actually be able to green the city of Kassel for documenta 7 with this campaign, he had to cope with a mammoth organizational task. In the course of the campaign, he made the experience that his collectors did not support him adequately in financing this campaign, even though they had previously seen an enormous increase in the value of his works. In order to actually raise the necessary 3.5 million DM, Beuys went so far as to appear in a commercial for the Japanese whiskey brand Nikka . The sentence: “I made sure the whiskey was really good.” Brought 400,000 DM alone. Beuys commented on this effort with the comment: “I have advertised all my life, but you should be interested in what I advertised . "

Multimedia forms of expression

Many of Joseph Beuys' art actions were captured in pictures by photographers such as Gianfranco Gorgoni, Bernd Jansen, Ute Klophaus or Lothar Wolleh . Beuys used some of these photographs as positive and negative reproductions for his multiples . In later Fluxus actions, Beuys used tonal and atonal compositions and noise collages, adding microphones, tape recorders, feedback , various musical instruments and his own voice. He worked with other artists, for example Henning Christiansen, Nam June Paik , Charlotte Moorman and Wolf Vostell . He particularly appreciated the American composer and artist John Cage . Works such as Eurasia and the 34th movement of the Siberian Synphony were created with the introductory motif of the division of the cross , 1966. In the action ... or should we change it , 1969, he played the piano and Henning Christiansen played the violin. Beuys swallowed cough syrup while Christiansen played a tape with sound collages made up of voices, birdsong, howls of sirens and other electronic sounds.

In 1969 Joseph Beuys was invited by the composer and director Mauricio Kagel to take part in his film Ludwig van for the 200th birthday of Ludwig van Beethoven . Beuys contributed the sequence Beethoven's kitchen with an action . The shooting took place on behalf of the WDR on October 4th in Beuys' studio.

Talk

The documenta 5 in 1972 is considered a turning point in Beuys' work; During the 100 days of the exhibition he made himself available for discussion with the public. In the following he developed an expanded concept of art , with which he outlined his idea of a “comprehensive creative transformation of life” and tried to capture it in the concept of social sculpture . "Shaping a social order like a sculpture, that is mine and the task of art." The core of this idea was the idea that "man" can be changed with the means of "art", thereby creating an opposite position to the in the means of the "class struggle" designed in the 1960s. The own person is, so to speak, the material and the person has the task of independently shaping this material like a sculpture as a work of art. At the same time, social sculpture also represents Beuys' expanded concept of art.

In the 1970s he intensified the spread of this idea through discussions and television appearances. In contrast to the statements of other artists, he was not concerned with creating interpretation aids for his works and their reception, but rather with dealing with the great questions of humanity in which he saw his works positioned.

In his lecture What is CAPITAL? During the “ Bitburger Talks ” at the beginning of 1978, Beuys developed his own system of economic values. In this, art plays an important role as the true capital of human abilities. The formula art = capital , which he wrote and signed on a ten-mark note in 1979, "can be taken literally, since he described the creativity and creative energy of the individual as the capital and potential of a society."

His often discussed statement, "Every human being an artist", which gives rise to a variety of interpretations, is discussed again in detail by Beuys in his famous speech on November 20, 1985 at the Münchner Kammerspiele . The speech was recorded on film and gives an immediate impression of Beuys as a speaker.

The German translation of a poem with the title “Everyone is an artist” (alternative title also “Instructions for the good life”, “Lebe!” Or named after the first line “Let yourself fall”) is often wrongly attributed to Joseph Beuys Been circulating on the internet for years. The English-language original ("How to be an artist") comes from the American artist SARK .

Room installations, showcases and objects

Room installations, showcases and objects

External web links

The monumental room installations, which were always created for a specific context of content and location, also made clear the way in which Beuys saw his work as a unity of forms, materials and practical and theoretical action. What he called the parallel process , with which he had named the juxtaposition of artistic work on “counter-images” and for him fundamental terminology, he finally picked up in public projects, such as the 7000 oaks for the city of Kassel , which he designed in 1982 documenta 7 began. The assessment that Beuys also lived this unity led to his characterization as the “last visionary in the art of the 20th century”.

Many of the objects in Beuys' installations, including various objects and relics in a group of similar display cases, are remnants of earlier actions. He understood his installation art as a transformation of the idea - as a thought that is depicted vividly as an “energy carrier” and should stimulate the viewer to reflect in a challenging or provocative way.

- “My objects must be understood as suggestions for implementing the idea of the plastic. They want to provoke thoughts about what plastic can be and how the concept of plastic can be and how the concept of plastic can be extended to the invisible substances and can be used by everyone. "

The artist had laid out most of his sculptures and objects years earlier in his extensive drawings and scores in order to realize them later. The same applies to his painterly work, which, however, is of a smaller scope.

In this complex of works Beuys also illustrated physical phenomena such as electricity . An example of this is the work Fond II , 1961–1967, consisting of two tables covered with sheet copper. In 1968, for example, at an exhibition in the Stedelijk van Abbe Museum in Eindhoven , he had the work high-voltage high-frequency generator for FOND II from 1968, which was included with the work , consisting of a car battery , three Leiden bottles , a glass tube wrapped in felt and a copper ring , electrically generated spark discharges , cracklingly between table and table , based on the principle of the Tesla transformer . This work, which was shown together with twenty-one other works in a separate room under the title Raumplastik , 1968, also at the 4th documenta , is now located with them in the Beuys block in Darmstadt.

The tram stop for the Venice Biennale in 1976 marked the beginning of a phase of large installations and space-related works in which the artist created his own memories as well as his own work contexts.

For the Venice Biennale in 1980 Beuys realized the first idea for an installation entitled Das Kapital Raum 1970–1977 , which was permanently displayed in 1984 in the Hallen für Neue Kunst in Schaffhausen , a former textile factory, as a two-story spatial sculpture.

Mercury thermometers can be found in several works , among other things placed on concert grand pianos in order to associate a connection between acoustic tense and temperature, for example in his late work Plight (German: Notlage) from 1985, which he had designed in 1958. Plight consisted of two claustrophobically arranged rooms that had been completely lined with felt rolls by Beuys (quasi soundproofed), and in which only one concert grand was set up, on top of which a school board and a fever thermometer - an allusion to the well-tempered piano by Bach .

The work Palazzo Regale was Beuys' last room installation, which he set up in 1985 in the Museo di Capodimonte in Naples and in which the artist took a retrospective position on his work by addressing his “own aesthetic and social activity” as “human self-determination”. In the former residence of the Bourbons , Beuys set up two brass showcases, which were accompanied by seven rectangular brass panels on the walls. The title alludes to the Palazzo Reale , the palace of the former viceroys in the center of Naples. The installation , which was purchased by the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in 1991, is, according to Armin Second , the then director of the art collection, “the triumphant summary” of Beuys' oeuvre.

Multiples

Multiples

external web links

Joseph Beuys saw in his multiples , his art objects produced as an edition, as potential carriers and vehicles for the dissemination of his ideas. Through the serial production of the respective object and its distribution, he intended to reach a larger circle of people.

Multiples from self-designed or found objects emerged at Beuys due to very different working methods as "the result of well-considered form finding in the studio, as relics of actions, products of processes or spontaneously from a specific occasion." Thus, before 1965, woodcuts and etchings were lost at Beuys In 1965 the graphic arts and from 1980 election posters for The Greens were integrated into the targeted production of his editions. Furthermore, photographs of his actions were used in his multiples; he overpainted them or arranged the pictures, often with crosses or other overpaintings, in boxes, which can be compared to the sewn-together Polaroids and machine photos in Andy Warhol's multiples, with Beuys dening emphasized documentary value, while Warhol focused on the idea of the series. One of the last Beuys multiples was the Capri battery from 1985.

Extension of the concept of art to social sculpture

Scientific and zoological studies led Joseph Beuys at the end of the 1960s to considerable reservations about what he believed to be a one-sided understanding of art and science and the view that the current empirical principle on epistemological justification, as seen in classical natural science, is not was enough. According to Beuys, "the expanded concept of art [...] was the goal of the path from traditional (modern art) to anthropological art."

Beuys came to the realization that the terms “art” and “science” are diametrically opposed to one another in the development of ideas in the West and that this fact is an occasion to look for a resolution of this polarization in perception. The examination of Rudolf Steiner's anthroposophy finally led to his concept of an expanded concept of art and a social sculpture , by which he understood a creative participation in society through art. At the end of 1972 Beuys joined the Anthroposophical Society as a member. However, he did not pay his membership fee for a long time, which is why the society did not, as some claim, expelled him again, but rather “regarded his membership as 'dormant'”.

For Beuys, a sculpture was more than a three-dimensional work; rather, he saw it as "[...] a constellation of forces [...] composed of undefined chaotic, undirected energies, a crystalline principle of form and a conveying principle of movement." the chaotic energy, he assigned the pole of cold, the crystalline form principle. For Beuys, these two poles were an energy that was able to transform the respective pole into its opposite. According to Beuys, warmth and cold are “supra-spatial plastic principles.” He developed his plastic theory during his studies of the Romantics Novalis , Philipp Otto Runge and Rudolf Steiner and, from 1973, Wilhelm Schmundt , after he told him at the 1st Annual Third Way in the International Achberg cultural center. In connection with this, Beuys sought to restore the lost unity of nature and spirit by countering purposeful thinking with a holistic understanding that includes archetypal, mythical and magical-religious connections. He transferred the plastic principle, which is used in the creation of a cooling "form" through the intervention of the sculptor ("movement"), in which the hot, warm raw material, which is in a state of "chaos", is transformed into a crystalline one Creative creation theory. By transforming this design principle into social coexistence, Beuys attempted to move the western world, which he saw suffered from materialism, to reorient it; With the help of the approach he formulated, a “new social movement” should be developed, as it was described, among other things, in 1978 in the call for alternatives . This new social organism was a work of art for Beuys, which he called the “social sculpture” (or sometimes: the “social sculpture”). All people who work on this new social system are "members of the living substance of this world."

Reception in the art business

Art criticism

An early critic of Beuys 'work was the Düsseldorf-based British art critic John Anthony Thwaites , who questioned Beuys' practices as a whole, mainly because of the gap between his utopian ideals and what Thwaites calls "gross self-aggrandizement" ) perceived. He also compared Beuys with neo-Marxists . His criticism culminated in the fact that he accused Beuys of operating an aestheticization of politics like Adolf Hitler . In the 1980s, Beuys' processing of National Socialism became an important topic among art historians in the United States. Benjamin Buchloh , Thomas McEvilley, Frank Gieseke and Albert Markert, among others, contradicted the prevailing opinion, especially in Joseph Beuys' circle, that he was the only artist of his generation who did not displace the Nazi era. Buchloh saw Beuys' behavior, in particular his later stylization and mythization of his plane crash over the Crimea in World War II - the artist had traced the use of felt in his work back to the material with which the Tatars , during their supposedly weeks of care for the seriously injured man, gave him saved life - as an indication that the artist joined the repression processes of the post-war period and “came to terms with their neurotic conditions”.

The American art critic Donald Kuspit , on the other hand, took the position that Beuys had not only processed his experiences in his work, but also turned them into positive ones; He therefore interpreted the mythization of his life, initiated by Beuys himself, not as a falsification, but as a deliberate reinterpretation with the aim of reassuring himself of his own memory. Kuspit found that the artist, in his form of processing, presented the audience, as it were on behalf of the Germans, with a creative approach to dealing with their own history.

The art critic Hans Platschek took the commercial success of the 1970s and 1980s as an opportunity to question the seriousness of the political claims of Beuys' social sculpture . In his book On Stupidity in Painting , Platschek reproached Beuys with “exploiting social conditions only for his own purposes and actually serving the capitalist art market particularly well with a metaphysically charged offer.” According to Platschek, Beuys is primarily a saturated one, with success bourgeois audience. "Metaphysicist in the supermarket, he delivers the unearthly free home." With his "request to take political conditions as magic, the world of goods as still life and social conditions as handicraft material", Beuys, serving a need for supposed profundity, has "in the West made a sensation in the markets. "

Beuys' approach of evaluating and resolving the problems of a modern society from the artist's point of view prompted various groups and associations, for example, from anthroposophically oriented “holistic teachings” and efforts from “natural medicine” to “self-help” initiatives To use elements of Beuys's thought structure for their goals; the sentence “Every human being is an artist”, detached from its context, served as evidence of a supposed arbitrariness in contemporary art and inspired painting circles and educators until the 1990s. “Everyone is an artist. I'm not saying anything about the quality. I just say something about the theoretical possibility that in every human being is present [...] The Creative I explain as the artistic, and this is my concept of art. "The Beuys biographer Hans Peter Riegel demanded Beuys because of its reception from the teachings of Rudolf Steiner ago to look at the background of folk esotericism and pre-Christian " occultism ". The filmmaker and connoisseur of the subject Rüdiger Sünner , on the other hand, held the accusation that Joseph Beuys had transported brown ideas into art as baseless in an interview. Also Eugen Blume dismissed the accusation, Beuys was looking for the "closeness to former Nazis".

Art market

During the years of Beuys's teaching activity at the Düsseldorf Art Academy (1966–1969), his importance on the art market grew at the same time. The trigger for this was the internationally acclaimed purchase of the entire Mönchengladbach Beuys inventory by Karl Ströher . At the same time, he had sold a valuable collection of Expressionists and informal post-war paintings in order to use the proceeds to finance the Beuys holdings and the purchase of a renowned Pop Art collection. With this coup the media had found a suitable topic; alongside the American superstar Andy Warhol , Joseph Beuys was able to establish himself as a European counterpart. The prices at the art fairs finally rose rapidly in 1969. As a result, Beuys took fourth place in the Kunstkompass , a world ranking of the 100 most important contemporary artists , in 1973 , ahead of Yves Klein and fifth place from 1974 to 1976, second in 1971 and 1978, and first in 1979 and 1980, both ahead of Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol.

The prices that Beuys' works achieved on the market sometimes met with incomprehension in view of the unusual materials used in art; For example, the purchase of the environment “ show your wound ” , consisting of old stretchers and grease, was commented by the Lenbachhaus in Munich in 1980 for 270,000 D-Marks as the “most expensive bulky waste of all time”.

In this context, the scandal surrounding the fat corner , which Joseph Beuys had installed in the Düsseldorf Art Academy in 1982 and which was removed posthumously in 1986 by a cleaner, was discussed as a “waste of taxpayers' money” . In the course of the process, a process came about that ended in a second instance with a settlement in which the state of North Rhine-Westphalia undertook to pay 40,000 DM in damages to the plaintiff and Beuys master student Johannes Stüttgen .

The untitled art object (bathtub) , created in 1960, also gained notoriety, which was processed into an anecdote of recent art history as Joseph Beuys' bathtub , after the objet trouvé , a bathtub with adhesive plaster and gauze bandages , cleaned at the celebration of a local SPD club in 1973 and had been used elsewhere. In this case, too, the owner, the art collector Lothar Schirmer , was awarded damages.

Art theory

The reception of Beuys' work today is consistently based on interpretations, contemporary quotes and documents by and about Joseph Beuys, as well as on image and film materials that document his actions. The more recent art historiography has so far essentially presented two approaches: the classification of the entire work according to its content and formal focus and the examination of the work of a world view draft in the context of classical modernism.

The division of the work includes the early cycle of a curriculum vitae-work run , the drawings, actions and room installations as well as the public speeches as part of the artistic work. In contrast to the statements of other artists, he was not concerned with creating interpretation aids for his works and their reception, but rather with dealing with the great questions of humanity in which he saw his works positioned.

For Beuys' work and for his thinking, a “network of holistic ideas ” is stated, the “ unsystematic openness” of which contradicts the conventional holistic concept of “coherence and coherence ”; the concept of a unity of work and life is no longer covered by a conventional concept of art. The possibilities of expanding the concept of art to all areas of life, especially in social sculpture , led, among other things, to a subsequent adaptation in anthroposophy , especially since Beuys himself had repeatedly referred to his reading Rudolf Steiner . This approach is evident in some of the artist's biographies.

He was hostile to modernity . Their rationalism destroys people's souls, which is more reprehensible than the Holocaust : “This society is ultimately even worse than the Third Reich . Hitler just threw the bodies in the ovens ”. The science and the democratic political system of the Federal Republic would the "principle Auschwitz " perpetuate.

Political activities

For Joseph Beuys, creative and political action was linked to his idea of the free human being and human beings as natural and social beings. Since 1971, his socio-political activities have focused on educational policy, with the aim of creating an alternative to the state training situation. He was against private and state capitalism , rather in favor of free and democratic socialism . At the same time, he set himself apart from the socialist concept of class: "I cannot work with the concept of class, [...] it is about the concept of man." For him, his art was liberation politics. The effect of Beuys' political commitment remained controversial. Rudi Dutschke noted in his diary: "Joseph was brilliant in art and ignorant in economics."

German Student Party (DSP)

On June 22, 1967, a few days after the death of the student Benno Ohnesorg , Beuys founded the German Student Party (DSP) in response to the simmering student unrest . To this end, he organized a "public explanation" by the DSP on the academy meadow in front of the Düsseldorf Art Academy with around 200 students, journalists and the AStA chairmen. On June 24, 1967, the "German Student Party" entered the register of associations - with Joseph Beuys (1st chairman), Johannes Stüttgen (2nd chairman) and Bazon Brock (3rd chairman).

In the founding minutes of Johannes Stüttgen, written on November 15, 1967, it was stated: “The necessity of the new party, whose main concern is the education of all people to the spiritual maturity, became especially in view of the acute threat from the materialism- oriented, unimaginative Politics and the associated stagnation were explicitly highlighted. ”Furthermore, the student party had committed itself to the Basic Law in its“ pure form ”. Further goals were "absolute lack of arms, a united Europe , the self-administration of autonomous members such as law, culture, economy, development of new perspectives on education, teaching, research, the dissolution of the dependence on East and West."

In order to dissolve the restriction to students, Beuys renamed the “German Student Party” in March 1970 to “Organization of non-voters, free plebiscite”. The goals were: “Expansion of political activities to all social groups with the aim of analyzing the structures of consciousness and action in society and using the knowledge gained to win people over to central individual and social change opportunities in an educational process analogous to 'plastic theory' . ”On June 19, 1971, the“ Organization for direct democracy through referendum ”was founded, in which the“ organization of non-voters ”was absorbed.

Organization for direct democracy through referendum

At documenta 5 1972, Joseph Beuys and his information office of the Organization for Direct Democracy were represented by referendum for the duration of the documenta daily, i.e. for 100 days. He discussed with the visitors about the idea of direct democracy through referendum and its possibilities of realization. There was always a long-stemmed red rose on the desk of the information office. Using the rose, Beuys explained the relationship between evolution and revolution to the visitors , which for him meant that the rose was an image of an evolutionary process leading to a revolutionary goal: “This blossom does not come about suddenly, but only as a result of an organic growth process that was laid out in this way is that the flowers are predisposed to germinate in the green leaves and are formed from them [...] So the flower is a revolution in relation to the leaves and the stem, although it has grown in organic transformation, the rose is only a flower possible through this organic evolution. "

In the program headings for "Organization for Direct Democracy through Referendum" the artist turned his democratic classification system of mental life, the right of life and economic life on the basis of the threefold idea of Rudolf Steiner and the ideals of the French Revolution on.

On October 8, 1972, the last day of documenta 5, Beuys conducted the legendary “boxing match for direct democracy through referendum” against Abraham David Christian- Moebuss under the direction of his pupil Anatol Herzfeld's referee after he had challenged his teacher. The boxing match took place in Ben Vautier's room in the Fridericianum . Beuys won the boxing match in three rounds with a point win.

Free International University (FIU)

The Free International University (FIU) or “Free International University for Creativity and Interdisciplinary Research”, as it was also called, was a non-profit organization founded on April 27, 1973 by Joseph Beuys, together with Klaus Staeck , Georg Meistermann and Willi Bongard recognized sponsoring association and should, as an “organizational place for research , work and communication, think through the questions of a social future.” The foundation for this was an educational draft, the first prerequisite for which was the fundamental renewal of the educational system. For an expanded educational program, the renewal of the entire educational system is necessary and with it a change in the organizational structure as well as the methods and content of teaching and the complete independence of schools and universities from the tutelage of the state.

Beuys did not want to develop a political program, but rather to create new competing educational institutions in order to gradually overcome the old institutions. In his opinion, the entire school sector should become autonomous in its concerns. Joseph Beuys was already working on the idea of designing and founding a free "University for Creativity and Interdisciplinary Research" in the course of the development of his teaching activity since the early 1970s. The FIU existed as a registered association until 1988.

Action group of independent Germans

“The system has become criminal, the state has become an enemy of man!” Beuys stated in 1976 and he decided to go into politics himself. In the 1976 federal elections in North Rhine-Westphalia , he ran as a non-party leading candidate for the Action Group for Independent Germans (AUD), which saw itself as “Germany's first environmental protection party”, and received 598 votes (3%) in his constituency of Düsseldorf- Oberkassel . This engagement earned him considerable criticism, since in the AUD ecological currents mixed with national conservative and strongly right-wing tendencies. According to Hans Peter Riegel , Beuys is said to have met August Haußleiter , a founding member of the AUD, at various anthroposophical congresses. Haussleiter himself was later involved in founding the Green Party, first becoming its spokesman and then federal chairman.

The green

Green lists have been established in the Federal Republic of Germany since the spring of 1977. In 1979 Joseph Beuys ran for the European Parliament as a direct candidate for "The Greens" and won Rudi Dutschke for joint campaign appearances. The AUD dissolved in favor of the "Greens" (today: Bündnis 90 / Die Grünen ). On January 11th to 12th, 1980 Beuys took part in the founding party convention of the "Greens" in Karlsruhe and on February 16, 1980 in their state members' meeting in Wesel . For the state election campaign in North Rhine-Westphalia, the “Greens” opened an information office in Düsseldorf on March 16; Beuys designed posters and carried out a campaign for the party. However, he was unable to enforce his own political ideas with the “Greens”.

From March 22 to 23, 1980, Beuys took part in their federal party conference in Saarbrücken . Before a panel discussion on the subject of “Dismantling democratic rights”, Petra Kelly and Joseph Beuys answered questions from the press on May 9, 1980 at the climax of the “Greens” election campaign in Münster . In 1982, during the final phase of the international arms race , Beuys appeared at events of the West German peace movement with Wolf Maahn's band and musicians from BAP as a political singer with the song Sonne instead of Reagan . On July 3, 1982, Beuys appeared in the ARD music program Bananas with Sun instead of Reagan as a pop interpreter. The BAP singer Wolfgang Niedecken , who says he was not privy to the preparations for the performance, reported that he only found out about the performance of his band with Beuys as the singer in front of the television. The text for the song was written by the copywriter Alaine Thomé, the music by Klaus Heuser . The Greens commissioned the protest song, which sparked some critical remarks about the level of performance. The recording with Beuys was released by EMI Electrona in 1982 as a single with a signed cover and the title Gathering Power on the back.

In November 1982, at the federal party congress in Hagen , Beuys declared his willingness to run again on the state list for the German Bundestag in North Rhine-Westphalia , and was then put up as a Bundestag candidate for the party in the Düsseldorf-Nord constituency on January 21, 1983. When he was not listed in one of the top places by the state delegates' conference, he withdrew his candidacy the following day. Beuys ended his direct collaboration with the Greens, but remained a member of the party until his death.

Awards and honors

- 1952: 4th Art Prize of the City of Düsseldorf (Applied Arts category); Exhibition iron and steel , "Eisenhüttenwerke", Düsseldorf

- 1974: Visiting professor at the University of Fine Arts in Hamburg

- 1976: Doctor of Fine Arts honoris causa , Nova Scotia College of Art and Design , Halifax

- 1976: Lichtwark Prize of the City of Hamburg

- 1978: Thorn Prikker honor plaque from the city of Krefeld

- 1978: Member of the Academy of Arts in Berlin, Fine Arts Department

- 1979: Kaiserring of the city of Goslar

- 1980: Visiting professor at the Städelschule in Frankfurt am Main

- 1980: Foreign honorary member of the Kungliga Konsthögskolan Stockholm , Stockholm

- 1984: Honorary citizen of the Bolognano community

- 1986: Wilhelm Lehmbruck Prize of the City of Duisburg

Posthumously

- Joseph Beuys Comprehensive School , Düsseldorf

- Joseph Beuys Comprehensive School , Kleve

- Joseph Beuys School, Neuss

- Joseph-Beuys-Allee, Bonn

- Joseph-Beuys-Allee, Kleve

- Joseph-Beuys-Ufer , Düsseldorf

- Joseph-Beuys-Strasse, Kassel

- Joseph-Beuys-Platz, Krefeld, the square in front of the Kaiser Wilhelm Museum

As part of the series “ German Painting of the 20th Century ”, the Deutsche Bundespost issued an 80-pfennig special postage stamp in his honor in 1993 with the motif Lagerplatz, 1962 - 1966 , Museum Abteiberg .

Exhibitions and retrospectives

- List of exhibitions by Joseph Beuys (1940–1986)

- 1973: Kunsthalle Tübingen , Tübingen, October 27 to December 2, Joseph Beuys. Drawings - Drawings by Caspar David Friedrich

- 1979/80: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum , New York, USA, November 2 to January 2 (retrospective)

- 1984: Kunsthalle Tübingen, Tübingen, September 8th to October 28th, Joseph Beuys. Oil colors 1949–1967

- 1985: Kunsthalle Tübingen, Tübingen, March 2nd to April 14th, 7000 oaks. 34 artists donate a work for Joseph Beuys' campaign

- 1988: Martin-Gropius-Bau , Berlin, Germany, February 20 to May 1 (retrospective)

- 1988: Kunsthalle Tübingen, Tübingen, May 12th to July 10th, Joseph Beuys. The secret block for a secret person in Ireland

- 1993/94: Kunsthaus Zürich , Zurich, Switzerland, November 26th to February 20th (retrospective)

- 1994: Museo Reina Sofía , Madrid, Spain, March 15 to June 6 (retrospective)

- 1994: Center Georges-Pompidou , Paris, France, June 30th to October 3rd (retrospective)

- 1996: Kunsthalle Tübingen, Tübingen, September 28th to November 24th, Warhol - Beuys - Twombly. Froehlich Foundation collection pads

- 2005: Tate Modern , London, Great Britain, February 4 to May 2 (retrospective)

- 2008/09: Museum für Gegenwart , Berlin, Germany, October 3 to January 25 (retrospective)

- 2009: 60 years. 60 works. Art in the Federal Republic of Germany , Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin, May 1st to June 14th; Joseph Beuys is represented for 1976 with the work Infiltration homogeneous for concert grand pianos , 1966.

- 2009/10: 8 Days - Beuys in Japan , Art Tower Mito ATM, Mito, Japan, October 31 to January 24

- 2010/11: parallel processes . Exhibition from September 11, 2010 to January 16, 2011 in the K20, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen , Düsseldorf. The exhibition takes place in the context of the Quadriennale Düsseldorf 2010.

- 2012: Advertising for art - an insight into the use of media and the artist's work using the example of postcards, posters, films, multiples and unique items. Municipal gallery in Park Viersen , October 7, 2012 to November 25, 2012

- 2012/13: My shaving mirror. From Holthuys to Beuys , Museum Kurhaus Kleve , September 9, 2012 to April 7, 2013 (after extension)

- 2013/14: Joseph Beuys: The Secret Block for a Secret Person in Ireland , drawings, Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin, December 17, 2013 to August 31, 2014

- 2016: Joseph Beuys. Work lines , Museum Kurhaus Kleve , May 1, 2016 to September 4, 2016

- 2017/18: Joseph Beuys - Immaculate images 1945–1985 . Works on paper from the Lothar Schirmer collection. Municipal Gallery in the Lenbachhaus Munich November 14, 2017 to March 18, 2018

- 2020: Block Beuys power plant, Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt , February 14, 2020 to May 24, 2020.

Collections

In his native Krefeld , Beuys is constantly present in the Kaiser Wilhelm Museum with an ensemble of works that he set up himself in 1984 and consists of seven objects.

Many of his works can be found in today's Museum Kurhaus Kleve , as well as in its premises in the former Friedrich-Wilhelm Bad (today Joseph-Beuys-Westflügel), which Beuys used as a studio from 1957 to 1964. An extensive complex of works by the artist can be seen in the Beuys block in the Hessisches Landesmuseum in Darmstadt . In Hau in Kleve are currently within the Stiftung Museum Schloss Moyland in Castle Moyland large holdings of works and archive materials to and from Joseph Beuys housed.

Further works by Beuys can be found in the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus , the Pinakothek der Moderne and the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung in Munich, in the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin (this is also where the Joseph Beuys Media Archive is located), in the Kunstmuseum Basel , in the Wilhelm Lehmbruck Museum , Duisburg, in the Kunstmuseum Bonn , in the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf, in the Museum Ludwig in Cologne, in the Städel in Frankfurt, in the Neue Galerie in Kassel and in the museum FLUXUS + in Potsdam. Beuys' works can also be found in the Center Georges-Pompidou in Paris, in MoMA in New York, in Chicago , Minneapolis and Tokyo as well as in other museums and galleries around the world.

Catalog raisonné

- List of art actions by Joseph Beuys (selection)

- List of environments and installations by Joseph Beuys (selection)

- List of sculptures and objects by Joseph Beuys (selection)

- List of multiples by Joseph Beuys (selection)

Movie

- Joseph Beuys: Everyone is an artist - Documentation by Werner Krüger from 1980.

- Joseph Beuys, Kleve. An Inner Mongolia - Documentation by Hannes Heer ; (WDR, 1991).

- Show your wound - art and spirituality with Joseph Beuys , film by Rüdiger Sünner , 2015, DVD, Absolut Medien

- Beuys from AZ Joseph Beuys expresses himself in short film excerpts in the original language using 72 terms on his life, thinking and work (2 parts, 2016).

- Beuys - Biography by Andres Veiel from 2017 (cinema release summer 2017).

literature

Beuys' writings