The Blind Man

The Blind Man was a daddy magazine that was published under this title in New York in 1917 in two issues in April and May of that year. The editors were Marcel Duchamp , Henri-Pierre Roché and Beatrice Wood . Other publications by the New York Dada movement were Rongwrong in July 1917 and New York Dada in April 1921.

The Blind Man I and II

The French artist Marcel Duchamp moved to New York in 1915. In 1916 he founded the Society of Independent Artists there with other artists , which sponsored jury-free exhibitions. She inspired Duchamp to publish the Dadaist publication The Blind Man with Henri-Pierre Roché and Beatrice Wood the following year , which invited authors to write on any topic.

The first eight-page edition appeared on April 10, 1917, to mark the opening of the Society of Independent Artists' first exhibition, with contributions by the British writer Mina Loy and an editorial comment from Roché. Since Duchamp and Roché were not American citizens, Beatrice Wood took responsibility for the paper against the wishes of her father, who did not agree with the contents of the magazine. It was not available for public sale but was offered to art galleries.

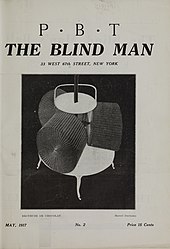

The second edition of The Blind Man, with Duchamp's chocolate crusher on the cover, came out in May and its main theme was the rejection of Duchamp's Ready-made Fountain by the board of the Society of Independent Artists. Fountain was a urinal that Duchamp purchased, labeled “R. Mutt ”signed and submitted anonymously as a sculpture. The issue shows Fountain as a photograph by Alfred Stieglitz on page 4 and on the opposite page an unsigned editorial, "The Richard Mutt Case", in which the rejection was discussed. The text is probably by Duchamp himself, although Beatrice Wood claimed the authorship for herself in her autobiography. Walter Arensberg , Mina Loy , Francis Picabia , Joseph Stella and Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia also contributed as authors .

Although the New York art world took careful note of The Blind Man , it was discontinued after the second edition. The reason for this was a bet between Roché and Francis Picabia that Dada honored. Winning a chess match between the two should determine which publication should be discontinued: The Blind Man or Picabia's magazine 391 , founded in Barcelona in early 1917 . Picabia won the match, and hence The Blind Man's release ended . 391 appeared until 1924.

Further publications in New York

A third publication with the same editors followed in July 1917, it was titled Rongwrong - a misprint, it was originally supposed to be "Wrongwrong", but was accepted - and contained, among other things, contributions by Duchamp and Carl van Vechten as well as documentation on the decisive factor Chess game by Picabia and Roché.

The four-page publication New York Dada , edited by Duchamp and Man Ray in April 1921 in one issue, was the only one of these publications to have the name "Dada" in the title. In order to be able to use the term, the editors had asked Tristan Tzara for a license. Tzara replied, “Dada belongs to everyone. Like the idea of God or that of the toothbrush ”. The title page of the issue contained a photo of Man Ray by Duchamp, disguised as a woman with a fur collar and bell hat named Rrose Sélavy, which was integrated in the ready-made Belle Haleine - Eau de Voilette (Beautiful Breath - Schleierwasser ), a perfume bottle. This was followed by Tzara's text as a letter, as well as a photograph by Alfred Stieglitz and a long poem by Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven , accompanied by two photos of her naked torso. The print was not sold, but distributed to friends in the hopes of promoting interest in Dada. Since this did not happen, Dada ended in New York and was only represented in Paris for a short time.

literature

- Arturo Schwarz (ed. Of the facsimile edition): Documenti Dada e Surrealisti , Archivi d'Arte del XX Secolo, Rome. Gabriele Mazzotta, Milan 1970

- Francis M. Naumann: New York Dada, 1915-23 . Abrams, New York 1994

- Calvin Tomkins : Marcel Duchamp. A biography . Hanser, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-446-20110-6

- Brigitte Pichon / Karl Riha (eds.): Dada New York. From rongwrong to ready-made . Edition Nautilus, Hamburg 1991, ISBN 978-3-8940-1181-9

Web links and sources

- toutfait.com : Illustrations of the covers and contents of the three editions

- The Art Institute of Chicago : Documents of Dada and Surrealism: Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection

Individual evidence

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography . Hanser, Munich 1999, p. 218

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography . Hanser, Munich 1999, p. 218 f

- ↑ Allan Savage: All artists are not chess players - all chess players are artists: Marcel Duchamp , tate.org.uk, January 1, 2008, accessed on December 19, 2013

- ↑ Quoted from Weblink Art Institute of Chicago, Documents of Dada and Surrealism in the Mary Reynolds Collection . In Dada Artifacts , Iowa City, Iowa, 1978, p. 72

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography , p. 273 f