Art of This Century

Art of This Century was a museum opened by Peggy Guggenheim on October 20, 1942 in Manhattan , New York , which was also a gallery. She commissioned the architect Friedrich Kiesler to design the rooms . The avant-garde gallery was managed by Guggenheim until the end of May 1947. That year she returned to Europe. The encounter between emigrated European artists and young American painters such as Robert Motherwell , Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko led to the mutual influence of Abstract Expressionism , and the center of art shifted from Paris to New York. In this respect, Guggenheim's exhibitions had a great influence on modern American art and can be compared with the presentations of the Armory Show , which took place in New York in 1913.

prehistory

Peggy Guggenheim had already opened a gallery in London on January 24, 1938 . The name "Guggenheim Jeune" was based on the one hand on the well-known gallery Bernheim-Jeune , on the other hand, her maiden name Guggenheim quoted her uncle, the art patron Solomon R. Guggenheim . Shortly before the opening of her own gallery, she took part in the opening of the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme in Paris on January 17th , organized by André Breton and Paul Éluard .

When Peggy Guggenheim returned to New York in 1941 after the phase of collecting in Paris and London, the dream, inspired by Herbert Read , of founding a museum for modern art in London was shattered due to the Second World War . However, the desire to be able to present the collection they had assembled in a museum lived on.

A 160-page catalog, which had been created from January 1942 to record Peggy Guggenheim's holdings, was published in May in an edition limited to 2500 copies; the cover was designed by Max Ernst . To the foreword by Peggy Guggenheim, there were introductory comments by André Breton , Hans Arp and Piet Mondrian . It was entitled Art of This Century , based on the suggestion of the painter Laurence Vail . On the advice of a friend, the lawyer and tax advisor Bernard J. Reis, Guggenheim integrated her commercial gallery into the non-profit museum for tax reasons in order to be able to deduct costs. She took the name for the museum and gallery from the catalog title. Initially, Jimmy Ernst , the son of her husband Max Ernst's first marriage , acted as secretary. Howard Putzel, a former gallery owner, later took on this role.

opening

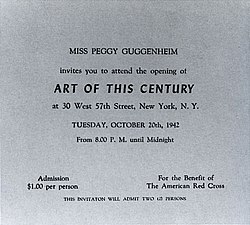

The museum and gallery based on plans by Friedrich Kiesler was opened by Peggy Guggenheim, "without financial help and with a lot of enterprise", on 30 West 57th Street, between the commercial art galleries, on October 20, 1942, with great public sympathy. The rooms were in a two-story, north-facing loft . 68 artists were represented in the exhibition with a total of 171 works. These included two Pablo Picassos , the early Cubist work by Georges Braque , works by Fernand Léger , Albert Gleizes and Louis Marcoussis, and a work by Marcel Duchamp . A late oil painting and two large drawings by Piet Mondrian hung alongside pictures by Dutch Constructivists and three pictures by Wassily Kandinsky . There were also three works by Constantin Brâncuși and three sculptures by Alberto Giacometti , including the bronze Femme égorgée (woman with a cut throat) (plaster 1932), cast in 1940 . Nine works by Paul Klee were exhibited and sculptures by Antoine Pevsner were accompanied by a work by Naum Gabo . Robert Delaunay and Francis Picabia were each represented with one work. Among the surrealists in the exhibited collection were works by Max Ernst and three works by Joan Miró . The chronological conclusion of the first exhibition was formed by the then younger artists such as Wolfgang Paalen , Joseph Cornell , Jean Hélion and Yves Tanguy .

The hostess appeared at the opening in a white evening dress and wore two different earrings; one, designed by Alexander Calder , symbolized abstract art , the other by Yves Tanguy the surrealist movement. She had set the entrance fee at one dollar and donated the sum to the American Red Cross.

The premises

| Glance into the surrealistic space |

|---|

| Friedrich Kiesler , 1942 |

| Art of this Century Gallery and Museum, New York

Link to the picture |

The museum consisted of three rooms. Cubist and abstract art could be seen in one, and the extensive collection of surrealist paintings and sculptures as well as kinetic art in the two adjoining rooms . The fourth room, Guggenheim's gallery, which was called “Daylight Gallery”, was reserved for the constantly changing exhibitions of short duration.

According to Peggy Guggenheim's own memory, Kiesler designed “the rooms in an original way”: “Pictures were not just shown, they were staged.” According to Guggenheim, the walls of the surrealist department were “irregularly curved” and made of eucalyptus: “The paintings were mounted on baseball bats [...] and seemed to float 30 centimeters free from the wall ”, spots lit up the pictures alternately on one side. In the department of abstracts and cubists, the entrance hall, the walls were draped with ultramarine blue fabric and the pictures were hung from the ceiling on strings at right angles to the wall. “In a corridor,” says Guggenheim, “a rotating stand with seven works by Paul Klee was set up, each of which rotated a further bit around its axis when visitors passed through a light barrier”.

Exhibition program

The program spanned five years, beginning with the opening exhibition in October 1942 and ending with a retrospective on the artist Theo van Doesburg at the end of May 1947. On average, ten exhibitions were held each year. In the beginning it was mainly group exhibitions, with solo exhibitions being the exception. As the only artist , a solo exhibition was held in the first season in honor of Jean Hélion , who married Peggy Guggenheim's daughter Pegeen in December 1944. As a result, the group exhibitions became increasingly rare, and in the last season in 1947 there was not a single one. The time in between was mainly characterized by two-person exhibitions.

| Composition with Pouring II |

|---|

| Jackson Pollock , 1943 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 63.9 x 65.3 cm |

| Hirshorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington DC

Link to the picture |

Although Peggy Guggenheim knew many European artists such as Hans Arp , Hans Theo Richter and Laurence Vail - the latter her first husband - but due to the war and the resulting lack of connection to Europe, they were not available to update the exhibition concept the program increasingly turned to American artists and sculptors. Guggenheim, for example, showed works by Jackson Pollock - four of whom were exhibited between 1943 and 1947 -, Hans Hofmann , William Baziotes , Mark Rothko , Robert Motherwell , David Hare , Charles Seliger, Richard Pousette-Dart , Clyfford Still, and others of whom they were some exhibited several times. Since the gallery was unable to sell much over the years, Peggy Guggenheim knew how to “cover up the embarrassing situation” by sending the works to the Peggy Guggenheim collection for new acquisitions .

| Birthday |

|---|

| Dorothea Tanning , 1942 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 102 × 65 cm |

| Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia

Link to the picture |

After Jackson Pollock's first exhibition in the gallery in November 1943, his work became the focus of Guggenheim's activities. According to her autobiography, Pollock received a contract for $ 150 a month and a share of the profits on works sold if they exceeded $ 2,700. A third of it should go to the museum. If the amount is not reached, compensation should be made through additional pictures. One painting exhibited by Pollock was Composition with Pouring II from 1943. Calvin Tomkins , Duchamp's biographer, described Guggenheim's first negative response to Pollock's submitted work scenographic figure with abstract and semi-abstract forms. When Piet Mondrian described the picture as the most exciting painting he had ever seen, she changed her mind. A solo exhibition by Mark Rothko took place in the gallery in 1945. In 1946, Hans Richter's first major solo exhibition followed in the USA.

Guggenheim also had a feel for issues that were still progressive at the time, which borrowed from the European institutions of the spring and autumn salons. In 1945 she showed a solo exhibition with the new chromatic spatial images of Wolfgang Paalen , who had become known in the USA through Julien Levy in 1940 with his fumages and his own art magazine DYN and had since lived in exile in Mexico. Guggenheim also devoted himself to younger talent and a repetitive focus on women's art , adding collage and showing off lesser-known artists who had poor references. In January 1943, for example, the “Exhibition by 31 Women” showed exclusively female painters with works by Valentine Hugo , Frida Kahlo , Louise Nevelson , Meret Oppenheim , Kay Sage , Dorothea Tanning and others. The meeting of Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning led to the estrangement of the Ernst couple; In 1946 Max Ernst married the artist. In 1945 the exhibition "The Women" followed, the exhibits came from, for example, Louise Bourgeois , Lee Krasner , Dorothea Tanning and Charmion von Wiegand .

The closure and return to Europe

Peggy Guggenheim closed the museum and gallery on May 31, 1947. She longed for Europe and moved to Venice ; she was exhausted by her work, and the gallery closed every year with a negative result. For example, the result for 1946 was a loss of $ 8,700. The contract signed with Jackson Pollock was taken over by Betty Parsons , who had opened a gallery in New York in October 1946, which was also joined by several other artists previously represented by Guggenheim.

In 1948 Guggenheim exhibited her collection at the Venice Biennale . Works by American artists Arshile Gorky , Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko were shown here for the first time in Europe. In the same year she acquired the unfinished Palazzo Venier dei Leoni with its large garden from the 18th century and had it converted. From 1949 she used it both as an apartment and as an occasional exhibition space for her collection, which was open to the public in the summer months from 1951. Admission was free, but a catalog had to be purchased for 75 cents as the exhibits were not labeled. Parts of the Peggy Guggenheim collection were secured in 1976 on the initiative of Thomas Messer , who was director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum from 1961 to 1988 , and transferred as part of the collection to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation , since Peggy Guggenheim holds the property rights to the foundation had transferred. Since 1980 the collection can be viewed in Venice as the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, which was also given to the Foundation in 1976 .

outlook

Post-war art did not arouse Guggenheim's interest, especially Pop Art , as a statement to a reporter shows: "She has achieved nothing and I have no idea what she wanted to achieve". Even the later works of the artists she exhibited were not particularly popular, especially for Mark Rothko. So she only bought contemporary works to invest money.

In recent years, art historians and critics have come to the view that Guggenheim played a crucial role in art history by promoting exiled European and then unknown young American artists in the development of Modernism and the emergence of Abstract Expressionism . In March 2007, the University of Pennsylvania hosted a symposium entitled Usable Pasts? American Art from the Armory Show to Art of This Century , which related the two exhibitions.

In 2011 the Friedrich Kiesler Foundation opened an exhibition in Vienna that offered a reconstruction as a walk-in model on a scale of 1: 3 of the surrealist exhibition space designed by Kiesler.

literature

- Dieter Bogner , Susan Davidson: Peggy Guggenheim & Frederick Kiesler. The Story of Art of This Century . Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern 2006, ISBN 978-3-7757-1557-7 (English)

- Mary V. Dearborn: Mistress of Modernism. The Life of Peggy Guggenheim . Houghton Mifflin, 2004, ISBN 0618128069 ; dt. I have no regrets! The extraordinary life of Peggy Guggenheim , Bastei Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 2007, ISBN 978-3-404-61615-2

- Peggy Guggenheim: Art of This Century. A museum dream come true . In: dies .: I've lived everything. The memoirs of the “femme fatale” of art . (Original: Peggy Guggenheim: Out of this Century. Confessions of an Art Addict , 1946/1960/1979) Munich 9th edition 1995; Pp. 245-259

- Peggy Guggenheim: Confessions of an Art Addict . Ecco Press, Hopewel, NJ 1997, ISBN 0-88001-576-4 ; dt. I've lived everything. Confessions of a passionate collector . Bastei-Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach, 10th edition 2008, ISBN 978-3-404-12842-6

- Bernd Klüser , Katharina Hegewisch (Hrsg.): The art of the exhibition. A documentation of thirty exemplary art exhibitions of this century . Insel Verlag, Frankfurt a. M. / Leipzig 1991, ISBN 3-458-16203-8 , pp. 102-109.

Web links

- Website of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection (English)

- The Artstory about the art gallery (english)

- Cover of the catalog for the first exhibition in 1942 , designed by Max Ernst

Individual evidence

- ^ Mary V. Dearborn: I have no regrets! , P. 11

- ^ Mary V. Dearborn: I have no regrets! , P. 290

- ^ Mary V. Dearborn: I have no regrets! , Pp. 186, 190

- ^ Thomas M. Messer: Peggy Guggenheim. ART OF THIS CENTURY. New York, 57th Street. October 20, 1942 to May 1947 . In: Bernd Klüser, Katharina Hegewisch (Hrsg.): The art of the exhibition. A documentation of thirty exemplary art exhibitions of this century , p. 102

- ↑ Quoted from Weblink: Catalog

- ^ Mary V. Dearborn: I have no regrets! , Pp. 271-274, 284

- ^ A b Thomas M. Messer, in: Bernd Klüser, Katharina Hegewisch (ed.): The art of exhibition. A documentation of thirty exemplary art exhibitions of this century , p. 104

- ^ Mary V. Dearborn: I have no regrets! , Pp. 280, 287

- ↑ Thomas M. Messer, in: Bernd Klüser, Katharina Hegewisch (ed.): The art of exhibition. A documentation of thirty exemplary art exhibitions of this century , p. 105

- ↑ Peggy Guggenheim: I have lived everything (1995), pp. 256-258

- ^ Mary V. Dearborn: I have no regrets! , P. 337

- ↑ Thomas M. Messer, in: Bernd Klüser, Katharina Hegewisch (ed.): The art of exhibition. A documentation of thirty exemplary art exhibitions of this century , p. 107

- ^ A b Thomas M. Messer, in: Bernd Klüser, Katharina Hegewisch (ed.): The art of exhibition. A documentation of thirty exemplary art exhibitions of this century , p. 108

- ↑ Peggy Guggenheim: I have no regrets! , Bastei Lübbe 2007, p. 473 f.

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography . Hanser, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-446-20110-6 , p. 191

- ^ Mark Rothko , www.guggenheim.org, accessed March 30, 2018

- ↑ Hans Richter , berlinerfestspiele.de, accessed on September 8, 2015

- ^ Mary V. Dearborn: I have no regrets! , P. 293 ff

- ↑ Charmion von Wiegand (1896–1983) in: Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, LLC, New York ( Memento from May 19, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Quoted from the website of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection

- ^ Mary V. Dearborn: I have no regrets! , P. 385 f

- ↑ Thomas Krens (preface): Rendezvous. Masterpieces from the Center Georges Pompidou and the Guggenheim Museums . Guggenheim Museum Publications, New York 1998, p. 102, ISBN 0-89207-213-X

- ↑ Peggy Guggenheim Collection. The Foundation . Retrieved June 27, 2010

- ^ Mary V. Dearborn: I have no regrets! , P. 406

- ^ Mary V. Dearborn: I have no regrets! , Pp. 365-370

- ↑ Usable Pasts? American Art from the Armory Show to Art of This Century (PDF; 560 kB), invitation

- ↑ Life form in art format. Surrealism on Display in Art of This Century ( Memento from October 16, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) on kiesler.org

Coordinates: 40 ° 45 ′ 49.4 " N , 73 ° 58 ′ 32.7" W.