Alberto Giacometti

Alberto Giacometti [alˈbɛrto dʒakoˈmetti] (born October 10, 1901 in Borgonovo , Stampa municipality ; † January 11, 1966 in Chur ) was a Swiss sculptor , painter and graphic artist of the modern age , who from 1922 lived and worked mainly in Paris . He remained connected to his native mountain valley Bergell ; there he met his family and devoted himself to his artistic work.

Giacometti is one of the most important sculptors of the 20th century. His work is influenced by cubism , surrealism and the philosophical questions about the human condition as well as by existentialism and phenomenology . Around 1935 he gave up surrealist work in order to devote himself to “ compositions with figures”. Between 1938 and 1944 the figures were a maximum of seven centimeters tall. They should reflect the distance at which he saw the model.

Giacometti's most famous works were created in the post-war period; In the extremely long, slender sculptures, the artist carried out his new experience of distance after a visit to the cinema, in which he recognized the difference between his way of seeing and that of photography and film. With his subjective visual experience, he did not create the sculpture as a physical replica in real space, but as “an imaginary image […] in its space, which is real and imaginary, tangible and inaccessible”.

Giacometti's pictorial oeuvre was initially a smaller part of his work. After 1957 figurative painting appeared on an equal footing with sculpture. His almost monochrome painting of the late period “cannot be assigned to any modern style”, said Lucius Grisebach reverently .

Life

Childhood and school days

Alberto Giacometti was born in Borgonovo, a mountain village in Bergell , near Stampa in the canton of Graubünden , as the first of four children of the post-impressionist painter Giovanni Giacometti and his wife Annetta Giacometti-Stampa (1871–1964). It followed as his siblings Diego , Ottilia (1904-1937) and Bruno . In the late autumn of 1903 the Giacomettis moved to Stampa in the “Piz Duan” inn, which was family-owned and has been run by his brother Otto Giacometti since the death of their grandfather Alberto Giacometti (1834–1933). The inn was named after the nearby Piz Duan mountain . In 1906 the family moved into a house diagonally across from the inn, which was the focus of the family for the next sixty years. Giovanni Giacometti converted the adjacent barn into a studio. From 1910 onwards the family had a summer house with a studio on Lake Sils through an inheritance in Capolago, Maloja , which became their second home. Alberto's cousin Zaccaria Giacometti , who later became professor of constitutional law and rector of the University of Zurich , often visited there.

In addition to his native Italian , Alberto Giacometti spoke German , French and English . His father taught him drawing and modeling. His uncle Augusto Giacometti was involved in the Zurich Dada circle with abstract compositions . Brother Diego also became a sculptor and furniture and object designer, and Bruno became an architect. Giacometti's godfather was the Swiss painter Cuno Amiet , who was a close friend of his father's.

In 1913 Giacometti made his first exact drawing, based on Albrecht Dürer's copper engraving, Ritter, Tod und Teufel , and painted his first oil painting, an apple still life on a folding table. At the end of 1914 he created his first sculptures, the heads of the brothers Diego and Bruno in plasticine . In August 1915 Giacometti began school at the Evangelical Middle School in Schiers . Due to the above-average performance and artistic skills, he was granted his own room, which he was allowed to set up as a studio.

education

Giacometti spent the spring and summer of 1919 in Stampa and Maloja, where he was constantly engaged in drawings and Divisionist painting. The decision to become an artist had been made, so that after four years he dropped out of school before graduating from high school and began studying art in Geneva in autumn 1919 . At the École des Beaux-Arts he learned painting and at the École des Arts et Métiers, sculpture and drawing. In 1920 Giacometti accompanied his father, who was a member of the Federal Art Commission at the Venice Biennale , to Venice , where he was impressed by the works of Alexander Archipenko and Paul Cézanne . In the lagoon city he was fascinated by the works of Tintoretto and in Padua Giotto's frescoes in the Cappella degli Scrovegni .

In 1921 he went on a study trip through Italy and stayed there with relatives of his family in Rome . Here he visited the city's museums and churches, filled sketchbooks with drawings based on mosaics, paintings and sculptures, attended operas and concerts and read, among other things, the writings of Sophocles and Oscar Wilde , which inspired him to draw. He fell miserably in love with his cousin Bianca; the work on her bust did not satisfy him. From the beginning of April he visited Naples , Paestum and Pompeii . His 61-year-old travel companion Pieter van Meurs suddenly died of heart failure in Madonna di Campiglio in September. Giacometti then returned to Stampa via Venice.

Living and working in Paris

Cubist beginning and handicraft livelihood

In January 1922 Giacometti went to Paris and took courses with Émile-Antoine Bourdelle for sculpture and life drawing at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière on Montparnasse , which he often did not attend for months. In the beginning, he had a lot of conversations with Swiss artists of the same age, such as Kurt Seligmann and Serge Brignoni . A fellow student, Pierre Matisse , later became his art dealer. With Flora Mayo, an American sculptor, he had a loose relationship until 1929; they portrayed each other in clay. In Paris he got to know the work of Henri Laurens , whom he met personally in 1930, as well as Jacques Lipchitz and Constantin Brâncuși .

Three years after starting his studies in Paris, Giacometti had his first exhibition at the Salon des Tuileries in Paris. When asked by Bourdelle, he showed two of his works in 1925, a head by Diego Giacometti and the post-cubist sculpture Torse (Torso) . The torso , reduced to a few angular block shapes, aroused the displeasure of his teacher Bourdelle: "You do something like this for yourself at home, but you don't show it."

In February 1925, his brother Diego followed him from Switzerland to the studio he had moved into in January of that year at rue Froidevaux 37. In the early summer of 1926 the brothers moved into a new, smaller studio in rue Hippolyte-Maindron 46, the Giacometti until his death maintained. Diego Giacometti found his job in the field of design and supported his brother in his work; he not only became Alberto's preferred model, but also his closest collaborator from 1930 onwards.

In order to earn a living, the brothers made decorative wall lights and vases made of plaster of paris for Jean-Michel Frank , whom they met in 1929 through Man Ray , and made jewelry for the fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli . Frank manufactured the bronze floor lamp Figure Version Étoile for Schiaparelli, also based on the design by Alberto Giacometti . Through Frank they got to know the Parisian haute société ; the Viscount de Noailles and his wife acquired sculptures and commissioned a 2.40 meter high stone sculpture, Figure dans un jardin (Figure in a garden) , a stele-like cubist composition, for the park of their Villa Noailles near Hyères , which in summer Was completed in 1932.

Member of the surrealists

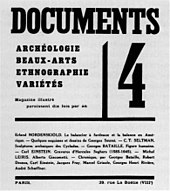

Since 1928 he has met artists and writers, such as Louis Aragon , Alexander Calder , Jean Cocteau , Max Ernst , Michel Leiris , Joan Miró and Jacques Prévert . In 1929, Leiris published a first appraisal of Giacometti's work in the fourth edition of the newly founded surrealist magazine Documents . Together with Joan Miró and Hans Arp , Giacometti was represented at the group exhibition in Pierre Loeb's Galerie Pierre in 1930 , where André Breton saw and bought Giacometti's art object , the plastic Boule suspendue (floating ball) . During a subsequent visit to Giacometti's studio in rue Hippolyte-Maindron, Breton persuaded the artist to join his group of surrealists . In 1933 Giacometti published poems in Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution as well as a surrealist text about his childhood, Hier, sables mouvants (Yesterday, drifting sand) . In the same year he learned the techniques of etching and engraving in the workshop of the Briton Stanley William Hayter , "Atelier 17" ; In 1933 he provided the surrealist writer René Crevel's book Les Pieds dans le plat with an illustration, followed by four copperplate engravings for Breton's L'Air de l'eau 1934.

Giacometti's father, who had been a strong point of reference for the artist, died in June 1933. Only a few works were created that year. Giacometti took part in other Surrealists' exhibitions, but began - again after a long time - to model from nature, which Breton saw as a betrayal of the avant-garde . In August 1934, Giacometti was together with Paul Éluard the best man and Man Ray photographer at the wedding of Breton with the French painter Jacqueline Lamba . A few months later, he withdrew from the group before an official expulsion could take place. During a dinner in December 1934, André Breton accused Giacometti of doing "bread work" for the Parisian furniture designer Jean-Michel Frank and therefore having reneged on the surrealist idea, and in 1938 at the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme in Paris called him a former Surrealists. As a result of the separation, Giacometti lost many friends, with the exception of René Crevel, who in June 1935, depressed and sick, took his own life.

New friends and an accident

After breaking with the Surrealists, Giacometti found himself in a creative crisis. He turned to other artists such as Balthus , André Derain and Pierre Tal-Coat , who had dedicated themselves to reproducing nature in art. He had already met Pablo Picasso in the surrealist circle, but a friendship between them did not develop until he was working on his monumental painting Guernica in 1937 . Giacometti was the only artist besides Matisse with whom he spoke about art, but never took his painting and sculpture very seriously. Although he understood that Giacometti was struggling for something, he saw this struggle - in contrast to Picasso's struggle for Cubism - as a failure because, according to Picasso, he would never achieve what he wanted and wanted from the sculpture «[... ] make us regret the masterpieces he will never create. "

A new friendship developed with the British Isabel Delmer, née Nicholas (1912–1992), who had married the journalist Sefton Delmer shortly after arriving in Paris in 1935 . Isabel Delmer became Giacometti's model for drawings. He made sculptures of her increasingly stretched and with extra-long legs. The first sculpture of her head from 1936, called The Egyptian , is reminiscent of Egyptian portraiture.

In October 1938 Giacometti suffered a serious traffic accident. While driving in Paris at night, an intoxicated woman driver lost control of her vehicle and hit him on the pavement on the Place des Pyramides. His foot was injured - his right metatarsus was broken in two places - and he ignored the restraint prescribed by his doctor until the fracture healed. Since then he had a walking problem and needed crutches and a cane until 1946. He often talked about this accident and described it as a decisive experience in his life, which "had the effect of an electric shock on his creative and personal life". Giacometti's biographer Reinhold Hohl rejected speculations that the artist had been traumatized for fear of an amputation and therefore equipped his later sculptures with oversized feet.

Meeting with Jean-Paul Sartre and an exhibition

In 1939 Giacometti met the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre and his partner Simone de Beauvoir in the Café de Flore . Not long after Sartre's first encounter with Giacometti, the philosopher wrote his major work L'Être et le Néant. Essai d'ontologie phénoménologique ( Being and Nothing . Attempt at a phenomenological ontology) , which was first published in 1943 and in which some of Giacometti's thoughts flowed. The phenomenology employed Giacometti life. Since his studies in Geneva he was looking for a new form of artistic expression. In 1939 he began to model busts and heads that were only the size of a nut.

Thanks to the mediation of his brother Bruno, Giacometti took part in the Swiss National Exhibition in Zurich in the summer of 1939 . A plaster drapery that he had planned for the facade cladding of the “Textile and Fashion” building turned out to be technically not feasible; the presentation of a tiny plaster figure on a large plinth in one of the 6 × 6 meter inner courtyards of the same building was refused because the work was viewed as a mockery of the artists involved. Instead, Giacometti's almost one meter high plaster Le Cube (The Cube) from 1933/1934, which had been shown at the Lucerne exhibition in 1935, was brought to Zurich and set up at ground level.

World War II in Geneva

When war broke out in September 1939, Alberto Giacometti and his brother Diego stayed in Maloja and returned to Paris at the end of the year. Giacometti buried his miniature sculptures in his studio in May 1940 - shortly before the German Wehrmacht invaded . The brothers fled Paris by bike in June, but turned back after cruel war experiences. On December 31, 1941, Alberto Giacometti, who was exempt from military service because of his handicap and had received a visa for Switzerland, traveled to Geneva while Diego stayed in Paris. From January 1942 to September 1945 Alberto Giacometti lived in Geneva, first with his brother-in-law, Dr. Francis Berthoud, later he took a simple hotel room; in the summer months he stayed in Stampa and Maloja.

Giacometti's sister Ottilia died in childbed in 1937, and grandmother Annetta helped raise the child. Tiny plaster figures were created on larger plinths in the hotel room, including the figure of his nephew Silvio. The plaster of paris Femme au chariot (Woman on the Carriage) , created in Maloja in 1942/1943, was Giacometti's only large-format work during his stay in Switzerland. In Maloja in 1943 he met the Swiss photographer Ernst Scheidegger , who photographed Giacometti's sculptures and for the first time published autobiographical and poetic texts by the artist in 1958 together with his photos in a book by Arche Verlag . In Geneva he met the publisher Albert Skira , for whose magazine Labyrinthe Giacometti wrote the autobiographical text Le rêve, le sphinx et la mort de T. (The dream, the sphinx and the death of T.) in 1946 .

Return to Paris and a change of style

From September 1945 Giacometti lived again in Paris, initially in a rented room on rue Hippolyte-Maindron, together with his long-time friend Isabel, who had separated from Sefton Delmer and returned from London. In December she left him, but continued to visit him occasionally in his studio; In 1947 she married Constant Lambert and after his death in 1951 Alan Rawsthorne . On the occasion of a planned exhibition at the Tate Gallery in London in 1962, Isabel brokered Giacometti's encounter with Francis Bacon , who had also portrayed her.

In 1946 Giacometti moved in with Annette Arm (1923–1993), whom he had met in Geneva in 1943 and married in 1949. With her as a model, a large number of drawings, etchings, paintings and sculptures were created. The sculptures became increasingly longer and thinner and showed the change in style that made him internationally known in the following decades: "pin" figures on high plinths gave way to slender figures meter-high, rod-thin figures with indistinct anatomy, but with precise proportions and only indicated heads and faces that are given a captivating look.

International success and the end of a friendship

Giacometti's first solo exhibition in 1948 at the Pierre Matisse gallery in New York , which represented the sculptor in the United States , was very successful . He became aware of collectors and influential art critics such as David Sylvester , whom Giacometti met at the exhibition. The exhibition, at which the slender figures were presented to a larger audience for the first time, established his fame in the Anglo-Saxon region. Jean-Paul Sartre wrote the almost ten-page essay La Recherche de l'absolu (The Search for the Absolute) for the exhibition catalog , and the American public saw Giacometti as a sculptor of French existentialism .

In 1950, the art historian Georg Schmidt bought two paintings, La Table and Portrait d'Annette , as well as the Bronze Place for the Emanuel Hoffmann Foundation in the Kunstmuseum Basel for 4800 Swiss francs, so Giacometti's first works entered a public collection that year Switzerland.

In 1951 the slender figures were shown for the first time in the Maeght Gallery in Paris, and numerous exhibitions in Europe followed. Giacometti received orders to make etchings for publications by Georges Bataille and Tristan Tzara . In November 1951 he and his wife visited the publisher Tériade in his country house in the south of France, after which they traveled to Henri Matisse , who lived in Cimiez near Nice. Pablo Picasso visited Vallauris the following day . Their long friendship ended after an argument. At occasional further encounters, Giacometti behaved politely but distantly.

Two biographers and new characters

In February 1952 Alberto Giacometti met his future biographer James Lord in the Café Les Deux Magots , who occasionally served him as a model for drawings. In 1964, when his portrait was being made, Lord was gathering material in sessions for the first book, A Giacometti Portrait (Alberto Giacometti - A Portrait) , published in 1965 by the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

In 1954, the year of the death of Matisse, who died in November, Giacometti drew the painter sitting in a wheelchair several times from the end of June to the beginning of July and again in September in order to prepare a commemorative coin commissioned by the French mint , which, however, was never minted . In 1956 Giacometti modeled a standing female figure, which he molded in different clay versions. His brother Diego made plaster casts of the 15 frontal and immobile figures. Ten were entitled in 1956 Les Femmes de Venise (The Women of Venice) in the French Pavilion at the Biennale in Venice to see, nine of which were later cast in bronze. This group of figures, consisting of "different versions of a single female figure that never received a final shape", was shown for the first time in 1958 as a bronze cast in the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York.

In November 1955, Giacometti met the Japanese professor of philosophy Isaku Yanaihara at Café Les Deux Magots , who was supposed to write an article about the sculptor for a Japanese magazine. Yanaihara became his friend and served as a model for him from 1956 ; he created several paintings and sculptures by 1961. The Japanese professor published the first biography on Giacometti in Tokyo in 1958.

Designs for the Chase Manhattan Bank

The Chase Manhattan Bank in New York , one of the largest banks in the world, planned in 1956 to liven up the spacious area in front of a new sixty-story building with works of art. The architect Gordon Bunshaft asked Giacometti and his American colleague Alexander Calder for designs. Giacometti agreed, although he was neither familiar with the local conditions in New York nor had he created works of the required size. He received a small model of the bank building and developed his designs until 1960: a female figure, of which he created four larger-than-life-size versions, a head that resembled Diego, and two life-size striders. Since Giacometti was not satisfied with the result, the order was unsuccessful. One work from the group is L'Homme qui marche I (The striding man I) .

Jean Genet and a new model

In 1957 the artist met the composer Igor Stravinsky , whom he drew several times. During this time he also met the French author Jean Genet and created three oil portraits and several drawings of him. Genet, in turn, wrote in 1957 about the artist L'Atelier d'Alberto Giacometti (The studio of Alberto Giacometti) . The text is said to have meant a lot to Giacometti because he saw himself in it. Picasso described Genet's 45-page work as the best book he had ever read about an artist. In 1959, Giacometti's work Trois hommes qui marchent (Three Striding Men) from 1947 was on view at documenta II in Kassel .

The acquaintance of the 21-year-old prostitute Caroline (real name Yvonne-Marguerite Poiraudeau), which Giacometti made in October 1959 at the Chez Adrien bar , led to an affair that lasted until his death. The connection with the young woman from the red light district turned out to be a burden for Annette and Diego Giacometti. Caroline became an important model during this period, and Giacometti created many portraits of her. The artist was now world famous and received large sums of money for his work from his dealers Pierre Matisse and Aimé Maeght. He did not change his habits, continued to live modestly but unhealthily - he ate little, drank a lot of coffee and smoked cigarettes. He distributed the acquired fortune to his brother Diego, to his mother until her death in January 1964 and to his nightly acquaintances. In 1960 he bought a house for Diego and apartments for Annette and Caroline, although the apartment was the more luxurious for his model.

Late years

Samuel Beckett , with whom Giacometti had known since 1937 and with whom he often debated the difficulties of being an artist in Parisian bars, asked him in 1961 to participate in a new production of Waiting for Godot , premiered in January 1953. Giacometti created in the Parisian Théâtre de l 'Odéon a barren tree made of plaster as a stage decoration in which the drama of human loneliness was shown, directed by Roger Blin in May 1961. The following year, Alberto Giacometti received the Grand Prize for Sculpture at the Venice Biennale , which made him famous around the world. In February 1963, he had to undergo an operation in February of that year because he had stomach cancer .

In 1964 Giacometti realized the multi-figure plaza composition in the courtyard of the Maeght Foundation in Saint-Paul-de-Vence , consisting of L'Homme qui marche II , Femme debout III and L'Homme qui marche I , and was at the documenta in Kassel again represented. In the same year his friendship with Sartre broke when his autobiographical book Les mots was published. Giacometti saw his accident and its consequences wrongly. Sartre had mistakenly named the Place d'Italie as the scene of the accident and quoted Giacometti as saying: “At last I am experiencing something! [...] So I wasn't meant to be a sculptor, maybe I wasn't even meant for life; I was not meant for anything. " Giacometti rejected a reconciliation with Sartre. The following year, despite poor health, he traveled to the United States for a retrospective of his works at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Giacometti died in 1966 in the Cantonal Hospital of Graubünden in Chur of pericarditis as a result of chronic bronchitis . He was buried in his birthplace, Borgonovo. Diego Giacometti placed the bronze cast of his brother's last work on the grave, the third sculpture by the French photographer Eli Lotar . Diego found the clay figure wrapped in a damp cloth in the studio. He placed his own little bronze bird next to it. In addition to the relatives and many friends and colleagues from Switzerland and Paris, museum directors and art dealers from all over the world, as well as representatives of the French government and federal authorities, attended the funeral.

estate

Alberto Giacometti Foundation

While the artist was still alive, the Alberto Giacometti Foundation was established in Zurich in 1965 from private and public funds by a group of art lovers led by Hans C. Bechtler and the Swiss gallery owner Ernst Beyeler , who acquired the Giacometti holdings from the Pittsburgh industrialist David Thompson. Thompson owned numerous important sculptures from the avant-garde period from 1925 to 1934 and copies of most of the major works from 1947 to 1950, Giacometti's most creative phases. The artist himself supplemented the later work with a group of drawings and several paintings. In 2006 close friends of Hans C. Bechtler, Bruno and Odette Giacometti donated 75 plasters and 15 bronzes from Alberto Gaicometti's estate to the foundation.

Today the foundation owns 170 sculptures, 20 paintings, 80 drawings, 23 sketchbooks, 39 books with marginal drawings and prints. This collection includes the life's work of Alberto Giacometti from his earliest to the last works in all essential aspects and numerous, surprising facets.

The collection of the Alberto Giacometti Foundation is largely kept in the Kunsthaus Zürich and presented in the permanent exhibition. Administration and documentation are also located here. A quarter of the original inventory is shown in the Kunstmuseum Basel and ten percent in the Kunstmuseum Winterthur .

Giacometti Foundation

- (Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti)

Another foundation, Fondation Giacometti (Institut Giacometti) in Paris, came about with great difficulty. Annette Giacometti died of cancer in 1993 in a psychiatric hospital. She left 700 works by her husband and archive material worth 150 million euros. Annette's brother and guardian Michael Arm denied the validity of her will from 1990, in which she had decreed that most of the Giacometti fortune should be used to set up the Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti . Further problems arose from the refusal of the Giacometti Association , which the widow had founded in 1989 as a preliminary step for the foundation, to dissolve and to release foundation capital. The planned foundation had to take legal action against the Giacometti association . The following disputes required large sums of capital, which had to be raised through auctions of Giacometti's works.

By decree of December 10, 2003, the then French Prime Minister put an end to the quarrels, so that the Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti could subsequently be established.

The Fondation founded together with the other rights holders - Alberto Giacometti Foundation, Zurich and the heirs of Silvio Berthoud (the armed comrades Berthoud) - in April 2004, the Comité Giacometti , the action against counterfeiting, expertise issues and issues permits reproduction. In 2011 she donated the Prix Annette Giacometti to protect the copyright for works of art and artists. Today, the Giacometti Foundation runs a research center with its Institut Giacometti with exhibitions, colloquia, a school, grants and publications.

Collections

The most extensive collections of Giacometti's works can be seen today at the Kunsthaus Zürich and the Fondation Beyeler in Riehen on loan from the Alberto Giacometti Foundation and at the Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti in Paris. The latter mainly owns objects from Giacometti's studio, including wall parts, furniture and books. Other important collections are in the Museum of Modern Art in New York and in the Fondation Maeght in Saint-Paul-de-Vence . The Carlos Gross Collection in Sent offers a good overview of Giacometti's graphic oeuvre .

plant

Giacometti placed high demands on his work all his life. Often he was plagued by doubts that led to the destruction of his work at night and the new beginning the next day. "In December 1965 he said that he would never achieve the goal he had set himself, for thirty years he had always believed that tomorrow would be the day [...]"

Drawings, paintings and lithographs

Alberto Giacometti

Autoritratto (self-portrait) Alberto Giacometti, 1921

Oil on canvas

82.5 × 70 cm

Fondation Beyeler , Riehen near Basel

Link to the picture

(please note copyrights )

Giacometti's childlike painting Still Life with Apples from 1913 shows the Divisionist style that was characteristic of his father Giovanni. While the father tried to standardize and revitalize the surface, the son looked at the object and its physicality. After painting beginnings at home and at school in Schiers, he continued painting during his studies in Geneva from 1919. Around 1925 the turn to sculpture in Paris almost completely displaced painting. The portraits of the father from 1930 and 1932, three paintings in 1937, including Pomme sur le buffet (apple on the buffet) and a portrait of the mother, as well as a woman portrait in 1944 remained exceptions. The pictures from 1937, which were created after his break with the Surrealists, differ stylistically from his earlier work and are now considered the beginning of his mature painting.

During the war years in Switzerland, drawing took up a large part of Giacometti's artistic activity. For example, he copied Cézanne from reproductions from books. These drawings served him to study the works of earlier artists and cultures and to clarify his relationship to them, as he understood his work to be a continuation. Because in his copies he did not analyze the originals in terms of their original function or art historical significance, but rather their structure and composition. Pencil drawings from the years 1946/47 of people moving around in the outdoor space document Giacometti's new conception of characters. As elongated, far-reaching stick figures, they are subsequently implemented in his sculpture and justify the so-called “Giacometti style”, in which the sculptor took on the phenomenological perception of the figures in space. Since every object has space around it and must always be viewed from a certain distance, the field of vision is inevitably occupied more vertically than horizontally, which partly explains the thinness of its figures.

Giacometti's painterly and graphic work after 1946 primarily deals with portrait heads and the human figure, which stimulated him to ever new metamorphoses. The tiny busts on the large plinths (1938 to 1945), with their perspective removed, refer to the artistic perspective of the draftsman and painter. The “stick figures standing like signs in space” (from 1947) are often provided with “painterly room housings” on the image carrier , in which the “portrayed persons appear as ectoplastic”, that is, “sculptured or mirrored bodies” from outside. Giacometti's paintings show a reduced color palette from gray-violet to rose-yellow to black and white, which "sound muted together" on the canvas.

Alberto Giacometti

Caroline, 1961

Oil on canvas

100 × 81 cm

Fondation Beyeler , Riehen near Basel

Link to the picture

(Please note copyrights )

The painterly work can be divided into the phases 1946 to 1956 and into the following years up to his death in 1966. The theme and painting style of his pictures are the same: frontal depictions of his wife Annette, his brother Diego, his mother and those of his friends and, in recent years, those of his lover Caroline; Landscapes, views of his studio or still life are occasional subjects. The background is varied. Works from the first phase show a depicted figure or an object in a wide, clearly recognizable environment, which can be identified as Giacometti's studio, for example, while in the second phase the central motif dominates the composition and an environment is only vaguely recognizable.

An occasion for lithographic work was Giacometti's first exhibition in the Maeght Gallery in 1951, which took place in June and July. He created illustrations for the gallery magazine Maeghts, Derrière le miroir , which accompanied the exhibition. The subjects of the illustrations were studio depictions. The numerous etchings and lithographs created from 1953 take up “the theme of the human figure as the axis of reference for the penetration of spatial dimensions, which characterizes his sculptural work” and “ modulates it in confrontation with the signs of the spatial perspective .” Giacometti's most important lithographic work is the portfolio Paris sans fin with 150 lithographs, they remind of the places and people in Paris that were important to him. Paris sans fin was published posthumously in 1969 by his friend, the art critic and publisher Tériade .

Sculptures, sculptures, objects

Early work and surrealist phase

Alberto Giacometti

Femme égorgée, 1932

Bronze (cast 1940)

23.2 × 57 × 89 cm

Center Pompidou , Paris

Link to the picture

On ne joue plus, 1932

marble, wood, bronze

4.1 × 58 × 45.2 cm

Collection Patsy R. and Raymond D. Nasher, Dallas, Texas

Link to the picture

(Please note copyrights )

In Giacometti's early phase, the post-cubist sculpture Torse (Torso) was created in 1925 ; this phase lasted until around 1927, when he researched African art and in particular the pictorial expression of the ceremonial spoons of the West African Dan culture, in which the hollow of the utensil spoon symbolizes the womb . His work Femme cuillère (spoon woman) dates from 1926 and is considered to be one of Giacometti's main works of that time. Giacometti's interest in this art was aroused by new publications dealing with the topic, such as the French edition of Carl Einstein's negro sculpture published in 1922 and by an exhibition in the Musée des Arts décoratifs in Paris in the winter of 1923/24 .

The phase described as surrealist lasted from 1930 to the summer of 1934 and finally ended in 1935 after he was excluded from the circle of surrealists. When Giacometti exhibited together with Hans Arp and Joan Miró for the first time in 1930 in Pierre Loeb's gallery , Paris, he showed a sculpture with an erotic symbolic effect, Boule suspendue (floating ball) , which consists of a strong metal frame with a movable structure inside. The sculptor described it in a letter to Pierre Matisse in 1948 as a sliced floating ball in a cage, sliding on a croissant . With this work Giacometti made the transition to mobile sculpture and object art . In addition, Giacometti created horizontally positioned sculptures such as the aggressive, sexual-looking object Pointe à l'œil (sting in the eye) , 1931, which shows the surrealistic connection between eye and vagina , as well as motifs of torture such as Main prize (endangered hand) , 1932.

In 1932, when Giacometti had been living in Paris for ten years, he created the "board game" On ne joue plus (The game is over) , a city of the dead with crater-like depressions, field boundaries and an open coffin, skeletons, two figures and the mirror-inverted title. It is a game in which "life and above all death become an unfathomable, unfathomable game". Femme égorgée (woman with a cut throat) , which was cast in bronze in 1940 and exhibited in October 1942 by Peggy Guggenheim in her newly opened New York Museum Art of This Century , also dates from that year . A drawing of the same title served as a template for an illustration of the text Musique est l'art de recréer le Monde dans le domaine des sons by Igor Markevitch in the surrealist magazine Minotaure , vol. I, 1933, issue 3–4, p. 78. The occasion was two crimes committed in Le Mans and Paris in February and August 1933 - the sadistic bloodshed by sisters Christine and Lea Papin and the poisoning of her parents by high school student Violette Nozière . Giacometti wrote in 1947 about his last surrealist figure, 1 + 1 = 3 , a cone-shaped work of plaster of paris about one and a half meters high , on which he was working in the summer of 1934: “He couldn't cope with it and therefore felt the need to do some studies to make nature […] ”. He then worked on two heads, Diego and a professional model served as his model; this change was one reason to accuse him of betraying the surrealist movement.

The slender bronzes

Alberto Giacometti

L'Homme au doigt, 1947

Bronze

178 × 95 × 52 cm

Tate Modern , London

Link to the picture

Quatre figurines sur base, 1950

Bronze, painted

162 × 42 × 32 cm

Tate Modern , London

Link to the picture

(Please note copyrights )

In 1935 Giacometti resumed studying nature and working on the human figure, and until 1945 primarily dealt with the model and the "superior power of space". Giacometti tried to reduce his sculptures “to the bones, to the point of indestructible” in favor of the space around them, with the result “that the figures and heads […] contracted more and more, reduced and became ever thinner.” The bust his brother Diego, who was a model for him over and over again during these years, "could finally be packed with the base in a small matchbox!" Another stylistic device to bring the spatial distance to the model in the sculpture into the appropriate form was the square base, which were much larger than the figures themselves. As an “external reason” to increasingly “bring 'phenomenological' experiences to bear in his sculptures”, his observation is quoted, “how Isabel thought of him in 1937 on the Boulevard Saint-Michel became distant, smaller and smaller, without losing their image, the visual memory. "

From 1946 onwards, Giacometti's figures grew increasingly in length, the bodies appeared thread-thin with their relatively gigantic feet. The surface structure and the stretching of the figures show a "relationship" with the sculptures Germaine Richiers , who like Giacometti studied at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Émile-Antoine Bourdelle's studio . It was only when the slender figures reached roughly human height, such as L'homme au doigt (Man with outstretched hand pointing) , in 1947, that Giacometti was recognized as a representative of French post-war sculpture; his earlier little figures were neglected and viewed as studies.

In 1947 and 1950 the two autobiographical sculptures Tête d'homme sur tige (head on a stick) and the bronze Quatre figurines sur base (four figures on a base), cast in 1965/66, were created . In the case of the latter, Giacometti positioned four figures, each 12 cm high, four dancers from the Parisian nightclub “Le Sphinx”, on a trapezoidal base and placed it in turn on a high-legged modeling table. The work was inspired by a last visit to his preferred brothel in view of the imminent closure of the public nightspots in 1946, after which his text Le rêve, le sphinx et la mort de T. (The dream, the sphinx and the death of T. ) was created.

The late work

Alberto Giacometti

La jambe, 1958

Bronze (two parts), patinated with gold

145 × 46.5 × 26.3 cm

Kunstmuseum Basel , Basel

Link to the picture

(Please note copyrights )

L'Homme qui marche I, 1960

Bronze (cast 1961)

Height: 183 cm

Link to the picture

(Please note copyrights )

Eli Lotar III, 1965

Bronze

65 × 25 × 35 cm

Beyeler Foundation, Basel

Link to the picture

(Please note copyrights )

From 1952 Giacometti created compact busts, heads and half-figures, among others after his brother, in addition to the slender figures and groups of figures such as Les Femmes de Venise (The Women of Venice) from 1956 and L'Homme qui marche I (The striding man I) from 1960 Diego, his wife Annette and Isaku Yanaihara, as well as three busts of the photographer Eli Lotar , which are "given as torso". Characteristic of the later sculptures are the protruding head, the bulging eyes, a nose that is only hinted at and a mouth cut as if with a knife, as for example in Buste d'homme (Diego) New York I (bust of a man [Diego] New York I) from 1965. The upper body, reduced to the shape of a cross, supports the head, which is seated on a narrow neck. Eli Lotar III from 1965 was Giacometti's last work that remained unfinished as a clay figure in his studio. The kneeling figure, the surface of which looks like a frozen cascade, is dominated by a narrow neck and head.

In 1958 Giacometti realized the sculpture La jambe (The Leg) , an isolated leg separated from the rest of the body with an open wound at the tip of the elongated thigh. He had this in mind as early as 1947, the year in which he realized sculptures such as Tête d'homme sur tige (head on a stick) or Le nez (the nose) in their respective versions. The cause for the emergence of these "isolated body parts" is on the one hand the collective trauma of the war after the Second World War and on the other hand the own traffic accident on the night of October 10, 1938 on Place des Pyramides in Paris. The sculptor had already sketched the larger-than-life-size “isolated leg” on the wall of his studio and, after years of suppression, was now able to work off the leg as “the keystone of a group of body fragments.” In 1934, André Breton asked the artist what his studio was to which Giacometti replied: "Two walking feet".

Fonts

At the time of Giacometti's surrealist phase, volume 5 of the magazine Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution of 1933 published poems by Giacometti, such as Poème en 7 espaces (poem in seven gaps) , The brown curtain (Le rideaux brun) , the text Scorched grass (Charbon d'herbe) and in volume 6 a surrealist text about his childhood, Hier, sables mouvants (Gestern, Flugsand) . These and other texts have been summarized in the book Alberto Giacometti. Ecrits from 1990, edited by Michel Leiris and Jacques Dupin (Ger. Yesterday, Flugsand. Schriften ). The letters, poems, essays, statements and interviews were written between 1931 and 1965. In the essay entitled My Reality , Giacometti writes that he wanted to survive with his art and be “as free and as powerful as possible” in order to “make his own To fight for fun? For joy? fighting, for the fun of winning and losing ”. This self-portrayal shows the existential philosophical reference to Jean-Paul Sartre and Jean Genet .

The publisher Albert Skira published in the last issue of his magazine Labyrinthe in 1946 the autobiographical text Le rêve, le sphinx et la mort de T. (The dream, the sphinx and the death of T.) , written by Giacometti in the same year . The artfully associatively told text deals with Giacometti's festering illness, which he contracted during his last visit to the Le Sphinx brothel before it was finally closed, and the subsequent reaction of Annette's and Giacometti's nightmare about the corpse of Tonio Pototsching, the caretaker who died in July 1946 of the studio complex in rue Hippolyte-Maindron. At the center of the dream is a huge spider with an ivory-yellow shell. It was not until 2002 that the manuscript, a notebook with the text, supplemented by drawings, found its way to the Alberto Giacometti Foundation in Zurich. The text contains two parts: After describing the context in which it was created and the narrative itself, Giacometti reflects on the problem of writing. The book was republished as a facsimile with a new translation in 2005.

Art market and fakes

Giacometti's oeuvre achieved high prices on the art market. L'Homme qui marche I reached a record price in an auction in February 2010 . It was even surpassed in an auction at Christie's in New York in May 2015. The most expensive sculpture is now his work doigt L'Homme au , which changed hands for approximately 141 million dollars in May 2015 the owner, about 35 million more than L'Homme qui marche I . Therefore, art forgeries of Giacometti sculptures are lucrative. In August 2009, 1000 forgeries that had been discovered near Mainz were confiscated by the police. Giacometti made the work of forgers easier in that he often had the same work carried out by different foundries at the same time. He did not process the casts himself, but left the chasing and patination to the craftsmen according to the buyers' wishes, so that the works always turned out differently. The lack of a binding catalog raisonné , which the two Giacometti foundations in Paris and Zurich are still working on to create, with the aim of producing casts during his lifetime, replicas and forgeries that appeared soon after Giacometti's death in 1966, offers further leeway for forgers to tell apart.

reception

Contemporary representations

"I know sculptures from Giacometti that are so powerful and so light that one would like to speak of snow that saves a bird's kick."

The French writer Michel Leiris , a friend of Giacometti's surrealist times, published the first text with factory photos on the sculptural work of the in the 4th edition of the surrealist magazine Documents, founded by Georges Bataille together with Leiris and Carl Einstein Artist. He wrote: “There are moments called crises, and these are the only ones that matter in life. Such moments happen to us when something external suddenly answers our inner call for it, when the external world opens in such a way that there is a sudden change between it and our heart. […] Giacometti's sculptures mean something to me because everything that arises under his hand is like the petrification of such a crisis. ”Leiris recognized early on what creative incentive for Giacometti should emanate from the recurring feeling of crisis.

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Alberto Giacometti, Stampa, Switzerland, 1961

Photography

Link to the picture

(Please note copyrights )

The photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson , himself influenced by Surrealism, made friends with Giacometti in the 1930s and accompanied him with his camera for three decades. The most famous recordings are from 1938 and 1961. Cartier-Bresson about Giacometti: "It was a pleasure for me to discover that Alberto had the same three passions as me: Cézanne, Van Eyck and Uccello." the Kunsthaus Zürich the exhibition The Decision of the Eye , which Cartier-Bresson had helped to design. With the photographs, some of which had never been shown before, the parallels in the work of the artist friends, which both Giacometti and Cartier-Bresson were shaped by the constant search for the instant decisif , the decisive moment, were to be shown.

Jean-Paul Sartre described Giacometti in 1947 in his essays on the fine arts, The Search for the Absolute , as a fascinating conversationalist and as a sculptor with a fixed “end goal to be achieved, a single problem that must be solved: how can one make a person out of stone without turning him to stone? ”As long as this is not solved by the sculptor or the art of sculpture,“ as long as there are only designs that interest Giacometti only insofar as they bring him closer to his goal. He destroys them all again and starts all over again. Sometimes, however, his friends succeed in saving a bust or a sculpture of a young woman or a youth from perishing. He lets it happen and goes back to work. [...] The wonderful unity of this life lies in the steadfastness in the search for the absolute. "

Jean Genet described Giacometti and his work in the 1957 essay, L'Atelier d'Alberto Giacometti , in contrast to Sartre's intellectual theses about the mutual friend out of feeling. “His statues give me the impression that in the end they take refuge in what secret frailty I don't know that gives them loneliness. [...] Since the statues are very tall at the moment - in a brown tone - when he stands in front of them, his fingers wander up and down like those of a gardener who cuts or plugs a rose trellis. The fingers play along the statue and the whole studio vibrates, lives. "

Current perception

The art historian Werner Schmalenbach compared the depiction of human loneliness in Giacometti's paintings with Francis Bacon's work. Like Giacometti, he formulates "the 'being exposed', the being thrown into the world of man in a spatial setting". Giacometti suggests this through the rigid frontality and the lost view, while Bacon depicts the total dislocation of the limbs and the death grimace of the face.

On the occasion of Giacometti's 100th birthday in 2001, the collector, art dealer and friend Eberhard W. Kornfeld said that he saw the revival of Giacometti's figurative drawings as an essential contribution to modern art. "But his art is also an expression of his time - what Sartre was for literature, Giacometti was in art: he is the painter of existentialism."

Alberto Giacometti

Diego assis, 1964

Bronze

58.5 × 19.7 × 32.5 cm

Alberto Giacometti Foundation, Zurich

Link to the picture

(please note copyrights )

The influence of ancient Egyptian art on Giacometti's work was demonstrated by an exhibition in the Egyptian Museum Berlin , Giacometti, the Egyptians . It was shown from the end of 2008 on the basis of examples in Berlin and from February 2009 in the Kunsthaus Zürich. Giacometti had already encountered the Egyptian sculpture in Florence during his first stay in Italy in 1920/21. He wrote to the family: "The most beautiful statue for him is neither a Greek nor a Roman and even less one from the Renaissance, but an Egyptian". The famous head portrait of Akhenaten (1340 BC) resembles Giacometti's self-portrait from 1921. With this self-portrait he finished his training with his father. The Parisian years with the approach to the avant-garde and the search for a stylization of the human form are summarized in the confrontation between the bronze works of Giacometti such as Cube (1933/34), which can be seen as based on Egyptian dice figures, and the cube statue of Senemut (1470 BC) in granite, of which he made a pencil drawing around 1937. The work of the post-war period is also based on Egyptian works. The recourse to Egyptian knee figures took place in the sculptures Diego assis (Diego sitting) and Lotar III , his last sculpture.

The art critic Dirk Schwarze, who has been familiar with the documenta exhibitions since 1972, formulated milestones in his book : documenta 1 to 12 from 2007, Giacometti had "inscribed himself in art history with his elongated, thin figures". The sculptor was not interested in the volume or the shape of the individual parts. He reduced the figure to its distant appearance, to its posture and movement. The figures have become signs of people that are understood everywhere - just as A. R. Penck later painted people as symbolic elements in his pictures.

On the occasion of a Giacometti exhibition of the Fondation Beyeler in Riehen near Basel in 2009, its curator Ulf Küster showed the artist and his works as a central figure in the context of the works of his artist family. The exchange with the family was very important for Alberto. His father, the painter Giovanni Giacometti , formed a special point of reference for him . In an interview, Küster said, among other things, that Giacometti had the idea of being the center of a system, as he described it in his late Surrealist text Le rêve, le Sphinx et la mort de T. , a center on which all events are centered related to him. Küster believes this is an important key to understanding his work. He points out that Giacometti never made the step into abstraction , but that his series formations, the "never-wanting and never-ending ability" corresponded to the basic conceptual idea of modernity. Alberto came from painting to sculpture. For example, the roughened surfaces of the later sculptures are a painterly technique. In his contribution to the exhibition catalog, Ulf Küster points out the difficulties of conceiving a Giacometti exhibition. With the many facets of his work only an approximation is possible, one reason for this is also Giacometti's artistic principle of perfection that can never be achieved. Although so far numerous exhibitions have dealt with Giacometti, Küster assessed Alberto's estate as not conclusively evaluated.

Giacometti's artistic influence

In Giacometti's surrealist period from 1930 to 1934, the artist was in the spotlight of the surrealist movement for the first time with his objects and sculptures. With his work from this time he influenced, for example, Max Ernst and the young Henry Moore . From 1948 onwards, it was the sculptures and paintings of his mature style that impressed his contemporaries and artist colleagues. The numerous Giacometti exhibitions that take place around the world are testament to the high artistic standards that he met with his work.

From May to August 2008, the exhibition En perspective, Giacometti was shown at the Musée des Beaux Arts de Caen . The Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, Paris, contributed around 30 loans of Giacometti's sculptures, objects, drawings and paintings as the initiator. They were related to works by contemporary artists: Georg Baselitz , Jean-Pierre Bertrand, Louise Bourgeois , Fischli & Weiss , Antony Gormley , Donald Judd , Alain Kirili , Jannis Kounellis , Annette Messager , Dennis Oppenheim , Gabriel Orozco, Javier Pérez , Sarkis , Emmanuel Saulnier and Joel Shapiro .

Appreciations

The German sculptor Lothar Fischer met Giacometti personally in 1962 at the Venice Biennale. He valued his conception of figure and space as well as shape and base and dedicated two sculptural works to his model in 1987/88 with the title “Hommage à Giacometti”.

In 1996 the first performance of the chamber opera Giacometti by the Romanian composer Carmen Maria Cârneci at the New Theater for Music in Bonn took place under her direction.

From October 1998 to September 2019, the Swiss banknote series featured a design in honor of Alberto Giacometti on the 100-franc banknote ; a portrait of the artist appears on the front, and on the back, along with two other works, his sculpture L'Homme qui marche I is depicted in four different perspectives.

On the 50th anniversary of the artist's death in 2016, the Centro Giacometti is participating in the organization of the memorial program in Bergell, which is coordinated by the municipality of Bregaglia. It also presents the Vision Centro Giacometti 2020 .

Films about Giacometti and his work

Jean-Marie Drot's 52-minute black and white film Ein Mensch unter Menschen from 1963 shows Giacometti in a film interview. Jean-Marie Drot was the first to succeed in filming the artist. The film describes him as a bohemian and perfectionist and shows more than 180 of his works.

Under the title What is a head? Michel Van Zèle produced a documentary film essay in 2000 on the question that occupied Giacometti throughout his life. Van Zele reconstructs Giacometti's lifelong search for the essence of the human head and lets contemporary witnesses from the past and present have their say, including Balthus and Giacometti's biographer Jacques Dupin . The running time is 64 minutes.

Both films have been combined on one DVD since 2006.

In 1965 the photographer Ernst Scheidegger , who has been shooting works by the artist since 1943, shot the film Alberto Giacometti in Stampa and Paris . It shows the artist at work on a painting by Jacques Dupin and in conversation with the poet while modeling a bust. The film was later supplemented by interviews.

Giacometti was involved in the 1955 portrait of Jean Genet in the television series 1000 Meisterwerke produced by WDR , which reported in 10-minute broadcasts from 1981 to 1994 about masterful paintings on German television , ORF and Bavarian television .

In 2001 Heinz Bütler made a documentary entitled Alberto Giacometti - The Eyes on the Horizon . It is based on the book Écrits by Giacometti. In interviews with companions and contemporary witnesses such as Balthus, Ernst Beyeler and Werner Spies , the artist is sketchily described in just under an hour. In another 25 minutes, Giacometti biographer James Lord tells about the artist's life. The strip was shown as a movie in 2007 and is available on DVD.

Final Portrait is the titleof Stanley Tucci's biography about the artist, whichcelebrated its world premiereon February 11, 2017 at the Berlin International Film Festival and which was released in German cinemas in August 2017.

Awards

- 1961: Prize for sculpture at the International Exhibition of Contemporary Painting and Sculpture, Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh

- 1962: Grand Prize for Sculpture at the Venice Biennale

- 1962: Guggenheim International Award for painting

- 1963: Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

- 1965: Honorary doctorate from the University of Bern , Bern

- The asteroid (11905) Giacometti , discovered in 1991, was named after the artist in 2001.

Exhibitions and retrospectives

- 1930: Miró - Arp - Giacometti , Galerie Pierre , Paris

- 1932: Galerie Pierre Colle, Paris

- 1934: Julien Levy Gallery, New York

- 1936: International Surrealist Exhibition , New Burlington Galleries, London

- 1938: Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme , Galerie Beaux-Arts, Paris

- 1942: Art of This Century , New York

- 1948: Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York

- 1951: Galerie Maeght , Paris

- 1955: Alberto Giacometti , Museum Haus Lange , Krefeld; Art Association for the Rhineland and Westphalia , Düsseldorf; Württembergischer Kunstverein , Stuttgart

- 1955: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum , New York (retrospective)

- 1956: Biennale di Venezia , Venice

- 1956: Kunsthalle Bern , Bern

- 1959: documenta II , Kassel

- 1964: documenta III , Kassel

- 1965: Museum of Modern Art , New York (retrospective)

- 1974: Alberto Giacometti. A Retrospective Exhibition , Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York (retrospective)

- 1977: Giacometti , Moderna Museet , Stockholm

- 1977: Alberto Giacometti: sculptures, paintings, drawings , Lehmbruck Museum , Duisburg

- 1978: Alberto Giacometti , Maeght Foundation , Saint-Paul-de-Vence

- 1978: Alberto Giacometti: A Modern Classic 1901–1966 , Bündner Kunstmuseum , Chur

- 1987/88: Nationalgalerie Berlin , Berlin (retrospective)

- 2001: 100 years of Alberto Giacometti - The retrospective . Kunsthaus Zürich, then until January 8, 2002 Museum of Modern Art, New York

- 2005: Henri Cartier-Bresson and Alberto Giacometti - The Decision of the Eye , Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris, Kunsthaus Zürich

- 2007/08: L'Atelier d'Alberto Giacometti , Center Georges-Pompidou , Paris

- 2008: En perspective, Giacometti , Musée des Beaux Arts de Caen, Le Château, Caen

- 2008/09: Giacometti, the Egyptian , Egyptian Museum Berlin , Kunsthaus Zürich

- 2009: Giacometti . Fondation Beyeler , Riehen near Basel

- 2009/10: From Rodin to Giacometti - Modern Sculpture , Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe

- 2010: Alberto Giacometti: The woman on the wagon. Triumph and Death , Lehmbruck Museum, Duisburg

- 2010: Giacometti & Maeght 1946–1966 , Maeght Foundation, Saint-Paul-de-Vence

- 2010/11: Alberto Giacometti. The origin of space . Retrospective of the mature work, Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg , November 20, 2010 to March 6, 2011; Museum der Moderne Salzburg , March 26 to July 3, 2011

- 2011: Alberto Giacometti - Seeing in the Work , Kunsthaus Zürich, March 11 to May 22, 2011

- 2011/2012: Alberto Giacometti, une retrospective , Collection de la Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, Museo Picasso, Málaga

- 2013: Alberto Giacometti. Encounters , Bucerius Kunst Forum , Hamburg, January 26 to May 20, 2013; parallel to this Giacometti. Die Spielfelder , Hamburger Kunsthalle , then Fundación Mapfre, Madrid

- 2014: Alberto Giacometti. La scultura , Galleria Borghese , Rome, February 5th to May 25th 2014

- 2014/15: Alberto Giacometti: Pioneer of Modernism , Leopold Museum , Vienna, October 17, 2014 to January 26, 2015

- 2015/16: Giacometti: Pure Presence, National Portrait Gallery , London, October 15, 2015 to January 10, 2016

- 2015/16: Alberto Giacometti. Masterpieces from the Maeght Foundation . Art Museum Pablo Picasso , Münster, October 24, 2015 to January 24, 2016

- 2016: Alberto Giacometti. A casa , Museo Ciäsa Granda, Stampa, June 5 to October 16, 2016

- 2016/17: Giacometti – Nauman , Schirn , Frankfurt am Main, October 28, 2016 to January 22, 2017

- 2016/17: Alberto Giacometti - Material and Vision , Kunsthaus Zürich , Zurich, October 28, 2016 to January 15, 2017

- 2017: Giacometti , Tate Modern , London, May 10 to September 10, 2017

- 2018: Alberto Giacometti & Francis Bacon , Fondation Beyeler, Riehen near Basel, April 29 to September 2, 2018

- 2018/19: Alberto Giacometti. A Retrospective , Guggenheim Museum Bilbao , October 19, 2018 - February 24, 2019

- 2019: Alberto Giacometti in the Museo del Prado , Museo del Prado , Madrid, April 2 - July 7, 2019

Selection of works

Sculptures and objects

The sculptures were mainly made of plaster, many were cast in bronze in the 1950s. The year of the bronze casting could not be found in all cases.

- 1925: Torse (torso) , plaster, 58 × 25 × 24 cm, Kunsthaus Zurich , Alberto Giacometti Foundation, Zurich. Fig.

- 1926: Femme cuillère (spoon woman) , bronze, cast 1954, 143.8 × 51.4 × 21.6 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum , New York. Fig.

- 1927: Le Couple (The Couple) , bronze, cast 1955, 59.6 × 38 × 17.5 cm, Museum of Modern Art , New York. Fig.

- 1930/31: Boule suspendue (floating sphere) , plaster of paris and metal, 60.6 × 35.6 × 36.1 cm, Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, Paris. Fig.

- 1931: Homme, femme, enfant (man, woman, child) , wood, metal, 441.5 × 37 × 16 cm, Kunstmuseum Basel .

- 1931: Pointe à l'œil (sting in the eye) , wood and black painted iron, 12.7 × 58.5 × 29.5 cm, Musée National d'Art Moderne , Paris. Fig.

- 1932: Femme égorgée (woman with a cut throat) , bronze, cast 1949, 23.2 × 57 × 89 cm, Scottish National Gallery , Edinburgh.

- 1932: Main prize (Endangered Hand) , wood, metal, 20 × 59.5 × 27 cm, Alberto Giacometti Foundation, Zurich. Fig.

- 1932: On ne joue plus (The game is over) , marble, wood, bronze, 4.1 × 58 × 45.2 cm, Collection of Patsy R. and Raymond D. Nasher, Dallas, Texas.

- 1933: La table surréaliste (The surrealist table) , bronze, 143 × 103 × 43 cm, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris. Fig.

- 1933/34: Le Cube (pavilion nocturne) (The Cube [nocturnal pavilion]) , bronze, 94 × 54 × 59 cm, Kunsthaus Zürich, Alberto Giacometti Foundation, Zürich. Fig.

- 1936: Tête d'Isabel (head of Isabel) , also called The Egyptian Woman , plaster, 30.3 × 23.5 × 21.9 cm, Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, Paris. Fig.

- 1937: Tête d'Isabel (head of Isabel) , bronze, private collection. Fig.

- 1937: Gerda Taro tomb , Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris (no longer preserved)

- around 1940: Petit homme sur socle (Little Man on a Pedestal) , bronze, 8.1 × 7 × 4.8 cm, Alberto Giacometti Foundation, Zurich. Fig.

- 1942/43: Femme au chariot (woman on the wagon) , painted plaster. Figure 153.5 × 33.5 × 35, car 10 × 40 × 35 cm, Lehmbruck Museum , Duisburg. A tribute to Giacometti's friend Isabel Nicholas.

- 1947: Femme debout ("Leonie") (standing woman ["Leonie"]) , height 53 cm, Peggy Guggenheim Collection , Venice.

- 1947: Le nez (The Nose) , bronze, cast 1965, 82 × 73 × 37 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Fig.

- 1947: L'Homme au doigt (man with outstretched hand pointing) , bronze, 176.5 × 90.2 × 62.2 cm, a cast is in the Tate Gallery , London.

- 1947: Tête d'homme sur tige (head on a stick) , bronze, height 59.7 cm, base: 16 × 14.9 × 15.1 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York.

- 1948–1949: La Place (The Square) , bronze, 21 × 62.5 × 42.8 cm, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice. Fig.

- 1950: L'Homme qui chavire (The staggering man) , 60 × 14 × 32 cm, Kunsthaus Zürich. Fig.

- 1950: Quatre figurines sur base (Four figures on a base) , bronze, painted, 162 × 42 × 32 cm, Tate Modern , London.

- 1950: Le chariot (The Carriage) , bronze, 167 × 62 × 70 cm, Alberto Giacometti Foundation, Zurich. Fig.

- around 1950: Diego , bronze, 26.8 × 21.5 × 10.5 cm, art collections of the Ruhr University Bochum . Fig.

- 1951: Le chien (The Dog) , bronze, 45 × 98 × 15 cm, Alberto Giacometti Foundation, Zurich. Fig.

- 1952: Figurine sur grand socle (figure on a large base) , bronze, 38.5 × 9 × 20.5 cm, Alberto Giacometti Foundation, Zurich. An example of the influence of ancient Egyptian art on Giacometti. Fig.

- 1954: Grande tête de Diego (Big Head Diego) , bronze, 65 × 39 × 22 cm, Alberto Giacometti Foundation, Zurich. Fig.

- 1956: Les Femmes de Venise (The Women of Venice) , group of figures of 9 versions I – IX, bronze, 1.05 to 1.56 cm, Fondation Beyeler , Riehen near Basel. Fig.

- 1958: La jambe (Das Bein) , copy 2/6, bronze (two parts), patinated with gold, 145 × 46.5 × 26.3 cm, Lehmbruck-Museum , Duisburg. Fig.

- 1960: L'Homme qui marche I (The striding man I) , copy 2/6, bronze, cast 1961, 183 × 95.5 × 26 cm. Fig. Planned Chase Manhattan Plaza group as a whole. Fig.

- 1960: L'Homme qui marche II (The Striding Man II) , bronze, cast in 1961, 187 cm high, Fondation Beyeler, Riehen near Basel.

- 1961: Buste de Caroline , bronze, 48 cm high, private collection

- 1961: Buste de Isaku Yanaihara (bust of Isaku Yanaihara) , bronze, 43 cm high Fig.

- 1962: Annette IV , bronze, cast 1965, 57.8 × 23.6 × 21.8 cm, Tate Gallery. London. Fig.

- 1964: Diego assis (Diego sitting) , bronze, 58.5 × 19.7 × 32.5 cm, Alberto Giacometti Foundation, Zurich. Fig.

- 1965: Buste d'homme (Diego) New York I (bust of a man [Diego] New York I) , copy 4/8, bronze, 55 × 29 × 14 cm, private collection, Switzerland.

- 1965: Eli Lotar III , bronze, 65 × 25 × 35 cm, Fondation Beyeler, Riehen near Basel. Fig.

Drawings and paintings

- 1915: La mère de l'artiste (The artist's mother) , pencil on white paper, 17 × 17 cm, Lefebvre-Foinet Collection, Paris (1971). Fig.

- 1921: Autoritratto Alberto Giacometti (self-portrait Alberto Giacometti) , oil on canvas, 82.5 × 70 cm, Fondation Beyeler, Riehen near Basel.

- 1937: La mère de l'artiste (The artist's mother) , oil on canvas, 65 × 50 cm, private collection.

- 1937: Pomme sur le buffet (apple on the buffet) , oil on canvas, 71.8 × 74.9 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art , New York. Fig.

- 1946: Portrait de Jean-Paul Sartre (Portrait of Jean-Paul Sartre) , pencil on white paper, 30 × 22.5 cm, private property.

- 1947: Standing figure - head en face - standing figure , pencil in two degrees of hardness, partly wiped, on ivory-colored cardboard, 50 × 64.5 cm, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart .

- 1949: Homme assis (Seated Man) , a painting depicting Diego. Oil on canvas, 80 × 54 cm, Tate Gallery, London. Fig.

- 1951: Triptyque (triptych) , lithographic chalk on chamois-colored paper, 38.5 × 28 cm, Galerie Claude Bernard collection, Paris (1971).

- 1955: Figure assise dans l'atelier (seated figure in the studio) , oil on canvas, 92 × 71 cm, Kunstmuseum Winterthur , Winterthur.

- 1955: Portrait de Jean Genet (Portrait of Jean Genet) , oil on canvas, 73 × 60 cm, Center Georges-Pompidou , Paris. Fig.

- 1957: Portrait de Igor Stravinsky (Portrait of Igor Stravinsky) , pencil on white paper, 40.3 × 30.5 cm, Robert D. Graff Collection, Far Hills , New Jersey (1971).

- 1958: Portrait d'Annette (Portrait of Annette) , oil on canvas, 65 × 54 cm, Batliner Collection , Albertina , Vienna. Fig.

- 1958: Portrait de Soshana (Portrait of Soshana) , pencil on paper, 50.8 × 33 cm, private collection. Fig.

- 1961: Caroline , oil on canvas, 100 × 81 cm, Fondation Beyeler, Riehen near Basel. Fig.

- 1962: Grand Nu (Large Nude) , oil on canvas, 174.5 × 69.5 cm, Fondation Beyeler, Zurich. Fig.

Etchings and lithographs

- 1951/52: Buste dans l'atelier (bust in the studio) , chalk lithograph, 50 × 65.5 cm, edition of 30, Kunstmuseum Basel

- 1953/54: Annette dans l'atelier (Annette in the studio) , chalk lithograph, 53.4 × 43.6 cm, edition of 30, Kunstmuseum Basel

- 1954: Les deux tabourets (The two stools) , etching, 26.2 × 20.8 cm, edition of 50, Kunstmuseum Basel

- 1957: L'homme qui marche (The Striding Man) , lithograph, 76.5 × 57 cm, edition of 200, Kunstmuseum Basel

- 1960: Buste II (Bust II) , lithograph, 65 × 50 cm, edition 150, Kunstmuseum Basel

- 1964: Portrait de Rimbaud (Portrait of Rimbaud) , etching, 29.9 × 24.8 cm, edition 97, Kunstmuseum Basel

Illustrated publications, correspondence

- 1946: Le rêve, le sphinx et la mort de T . Labyrinths , Nos. 22-23, December, Paris; dt. The dream, the sphinx and the death by T. Edited and translated by Donat Rütimann. Scheidegger & Spiess, Zurich 2005, ISBN 978-3-85881-170-7

- 1969: Paris sans fin , 150 lithographs, published posthumously by Tériade , Paris; New edition Buchet-Chastel, Paris 2003, ISBN 978-2-283-01994-8 Fig.

- 1990: Alberto Giacometti. Écrits . Edited by Michel Leiris and Jacques Dupin. New edition Hermann, Paris 2007, ISBN 978-2-7056-6703-0 ; German: Yesterday, drifting sand. Writings , new edition Scheidegger & Spiess, Zurich 2006, ISBN 978-3-85881-178-3

- 2007: Alberto Giacometti, Isabel Nicholas, Correspondances . Edited and with a foreword by Véronique Wiesinger, Fage Éditions, Lyon, ISBN 978-2-84975-121-3

Examples of book illustrations

- 1933: René Crevel : Les Pieds dans le plat (frontispiece) Fig.

- 1934: André Breton : L'Air de l'eau

- 1947: Georges Bataille : Histoire de rats

- 1961: Michel Leiris : Vivantes cendres, innomées

- 1962: Miguel de Cervantes : La Danse du château (frontispiece)

Literature (selection)

Testimonies from family and companions

- Felix Baumann (ed.), Roland Frischknecht: Bruno Giacometti remembers. With a catalog raisonné of the buildings by Roland Frischknecht . Scheidegger & Spiess, Zurich 2009, ISBN 978-3-85881-248-3

- Jean Genet : L'Atelier d'Alberto Giacometti , 1957; German Alberto Giacometti , Scheidegger & Spiess, Zurich 2004 (new edition), ISBN 3-85881-051-7 .

- Marco Giacometti / Claudia Demel: Alberto Giacometti. I don't understand life or death. Photo documentation on the 50th year of Alberto Giacometti's death, Salm Verlag, 2016, ISBN 978-3-7262-1432-6

- Elisabeth Ellenberger: Alberto Giacometti. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . January 11, 2018 , accessed March 3, 2020 .

- James Lord : A Giacometti Portrait , 1965, German Alberto Giacometti. A portrait , List, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-548-60097-2

- Jean-Paul Sartre : The Search for the Absolute: Texts on Fine Art . Translated from the French by Vincent von Wroblewsky. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1999, ISBN 978-3-499-22636-6

- Ernst Scheidegger , Ursula von Wiese: Alberto Giacometti. Writings, photos, drawings . Arche, Zurich 1958

- Ernst Scheidegger: Alberto Giacometti. Traces of a friendship . Scheidegger & Spiess, Zurich 1990; 2nd revised edition 2000, ISBN 978-3-85881-109-7

- Donat Rütimann: Alberto Giacometti in Schiers: 1915 to 1919. In: Bündner Jahrbuch: Zeitschrift für Kunst, Kultur und Geschichte Graubünden, Vol. 43, 2001, pp. 71–89 ( digitized version ).

Biographies

- Yves Bonnefoy : Alberto Giacometti. Biography d'une oeuvre . Flammarion, Paris 1991; German Alberto Giacometti. A biography of his work . Benteli, Bern 1992, ISBN 3-7165-0848-9

- Jacques Dupin : Alberto Giacometti . Maeght, Paris 1962

- Reinhold Hohl : Alberto Giacometti . Gerd Hatje, Stuttgart 1971, 2nd edition 1987, ISBN 3-7757-0013-7

- James Lord: Alberto Giacometti , (1983). German, new edition Scheidegger and Spiess, Zurich 2004, ISBN 3-85881-157-2 , as paperback edition Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2009, ISBN 978-3-596-18368-5

- Claude Delay: Alberto and Diego Giacometti. The hidden story . Römerhof Verlag, Zurich 2012, ISBN 978-3-905894-18-9

Investigations, exhibition catalogs and work directories

- Agnès de la Beaumelle: Alberto Giacometti. Le dessin à l'oeuvre . Center Georges-Pompidou , Musée National d'Art Moderne , Paris 2001

- Peter Beye , Dieter Honisch : Alberto Giacometti , Prestel-Verlag 1987 and Staatliche Museen Prussischer Kulturbesitz , ISBN 3-7913-0846-7 . Catalog for the exhibition in the Nationalgalerie Berlin and Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, 1988

- Tobia Bezzola (eds.): Henri Cartier-Bresson and Alberto Giacometti: The decision of the eye . Scalo, Zurich 2005, ISBN 978-3-03939-008-3 . Catalog for the exhibition at the Kunsthaus Zürich, 2005

- Markus Brüderlin , Toni Stooss (Ed.) Alberto Giacometti: The origin of space . Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern-Ruit 2010, ISBN 978-3-7757-2714-3 . Catalog for the exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg 2010/11; Museum der Moderne Salzburg , 2011

- Casimiro di Crescenzo: In the Hotel Régina. Alberto Giacometti before Henri Matisse . Piet Meyer Verlag, Bern 2015, ISBN 978-3-905799-32-3

- Alberto Giacometti. Drawings , catalog for the memorial exhibition in the Kestner Society , Hanover 1966, with introductory notes by Wieland Schmied

- Reinhold Hohl, Dieter Koepplin: Alberto Giacometti. Drawings and prints . 2nd edition, Hatje Cantz, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-7757-0161-3

- Christian Klemm: The collection of the Alberto Giacometti Foundation . Zurich Art Society, Zurich 1990

- Christian Klemm, Carolyn Lachner: Alberto Giacometti . Catalog for the exhibition at the Kunsthaus Zürich, 2001 and The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2001/2002, Nicolai, Berlin 2001, ISBN 978-3-87584-053-7

- Ulf Küster: Alberto Giacometti: Space, Figure, Time . Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern 2009, ISBN 978-3-7757-2372-5

- James Lord: Alberto Giacometti Drawings . A Paul Bianchini Book, New York / Graphic Society Ltd./ Greenwich, Connecticut, 1971

- Herbert C. Lust: Giacometti. The Complete Graphics. And 15 Drawings . Tudor Publishing Company, New York 1970

- Alberto Giacometti. Drawings, unique prints and additions to the catalog raisonné of Lust prints . Munich, Galerie Klewan, 1997. With texts by Andreas Franzke, Bruno Giacometti, Christiane Lange, James Lord. Munich, 1997

- Axel Matthes (ed.), Louis Aragon (co-author): Paths to Giacometti . Matthes and Seitz, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-88221-234-9

- Matti Megged: Dialogue in the Void. Beckett and Giacometti. Lumen Books, New York 1985, ISBN 978-0-930829-01-8

- Suzanne Pagé : Alberto Giacometti. Sculptures. peintures. dessins . Musée d'art Moderne de la Ville de Paris , Paris 1991/1992

- Angela Schneider (Ed.): Alberto Giacometti: Sculptures - Paintings - Drawings . With contributions by Lucius Grisebach, Reinhold Hohl, Dieter Honisch, Karin von Maur and Angela Schneider. Prestel Verlag, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-7913-3870-5

- Emil Schwarz: Body is body is body in infinite space, homage to Alberto Giacometti , a poetic approach with the essay In space, time grows . NAP Verlag, Zurich 2009, ISBN 978-3-9521434-9-0

- Jean Soldini: Alberto Giacometti. L'espace et la force . Éditions Kimé, Paris 2016, ISBN 978-2-84174-747-4

- Alberto Giacometti - A narrative place . In: Markus Stegmann: Architectural Sculpture in the 20th Century. Historical aspects and work structures , Tübingen 1995, pages 100–116.

- Toni Stooss, Patrick Elliott, Christoph Doswald: Alberto Giacometti 1901–1966 . Kunsthalle Wien , Vienna 1996

- Véronique Wiesinger / Ulf Küster: Giacometti , catalog, published by the Fondation Beyeler : Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern 2009, ISBN 978-3-7757-2348-0

new media

- (DVD, VHS, VOD)

-

Alberto Giacometti , two documentaries by Jean-Marie Drot and Michel Van Zèle , Ein Mensch unter Menschen (1963) and Was ist ein Kopf (2001)

arte Edition / absolut Medien , DVD 2001, 161 min. (B / w and color - fr , de, en, sp), on arte-edition.de / also VOD - see: Alberto Giacometti on boutique.arte.tv, Alberto Giacometti on sales.arte.tv -

Alberto Giacometti - a film by Ernst Scheidegger , directed by Ernst Scheidegger ; Camera Peter Münger , Rob Gnant , Othmar Schmid ; Text by Jacques Dupin , Ernst Scheidegger; Editing by Peter Münger, Kathrin Plüss ; Music Armin Schibler

2nd revised version (shot 1965, expanded 1968), VHS, 50 min. (Color), Scheidegger & Spiess , Zurich 1983, ISBN 978-3-85881-905-5 , on Scheidegger-spiess.ch

Web links

- Centro Giacometti in Bergell, centrogiacometti.ch (of the Centro Giacometti Foundation based in Stampa)

Lexicons

- Elisabeth Ellenberger: Alberto Giacometti. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Thierry Dufrêne: Giacometti, Alberto. In: Sikart

Libraries, online catalogs

- Publications by and about Alberto Giacometti in the Helveticat catalog of the Swiss National Library

- Works by and about Alberto Giacometti in the German Digital Library

- Literature by and about Alberto Giacometti in the catalog of the German National Library

- Materials by and about Alberto Giacometti in the documenta archive

biography

- Alberto Giacometti - Chronology (PDF, 7 pages), MoMA , 2011, on moma.org (en)

Exhibitions, collections

- Alberto Giacometti Foundation, Kunsthaus Zurich

- Alberto Giacometti Foundation , on the foundation's website, giacometti-stiftung.ch (de, fr, en - holdings for the most part in the Kunsthaus Zürich, there are ongoing selections there, one quarter in the Kunstmuseum Basel , one tenth in the Kunst Museum Winterthur )

-

Alberto Giacometti Foundation - The most significant museum collection in private collections , on Web of the Kunsthaus Zurich , kunsthaus.ch (de, fr, en)

there in the collection - The highlights of the collection listed

- Fondation Giacometti (Institut Giacometti / Giacometti Institute) in Paris, fondation-giacometti.fr (fr, en)

- Alberto Giacometti on kunstaspekte.de

Movie

- A Man Among Men: Alberto Giacometti , Jean-Marie Drot , 1963, on UbuWeb , ubu.com

- Alberto Giacometti , director Ernst Scheidegger , camera Peter Münger, second, revised version, 1998, on youtube.com

- Alberto Giacometti, qu'est-ce qu'une tête? , Michel Van Zèle, 2000, on WorldCat (together with A Man Among Men )

- Final Portrait - The story of Swiss painter and sculptor Alberto Giacometti , Stanley Tucci , 2017, on de.wikipedia

additional

- Alberto Giacometti on artcyclopedia.com

References and comments

- ^ Alberto Giacometti. cosmopolis.ch, accessed on April 13, 2010 .

- ↑ Angela Schneider: As if from a great distance. Constants in Giacometti's work. In: Angela Schneider: Giacometti. P. 71

- ↑ Dieter Honisch: Big and small with Giacometti. In: Angela Schneider: Giacometti. P. 65

- ↑ Reinhold Hohl: Chronicle of life. In: Angela Schneider: Giacometti. P. 26

- ↑ Lucius Grisebach: The painting. In: Angela Schneider: Giacometti. P. 82

- ^ Andreas Kley: From Stampa to Zurich. The constitutional lawyer Zaccaria Giacometti, his life and work and his family of artists from Bergell. Zurich 2014, p. 89 ff.