Gottfried Keller

Gottfried Keller (born July 19, 1819 in Zurich ; † July 15, 1890 there ) was a Swiss poet and politician .

Excluded from higher education because of a youth prank, he began an apprenticeship to become a landscape painter . He spent two years studying in Munich , from where he returned to his hometown in 1842 penniless. Under the influence of the political poetry of the Vormärz , he discovered his poetic talent. At the same time he took part in the militant movement that led to the state reorganization of Switzerland in 1848 .

When the Zurich Government him a travel fellowship granted, he went to Heidelberg at the Heidelberg University to study history and political science, and from there on to Berlin to train himself to theater writer. Instead of dramas , however, novels and short stories emerged , such as Der Grüne Heinrich and Die Menschen von Seldwyla , his most famous works. After seven years in Germany, he returned to Zurich in 1855, a recognized writer, but still penniless. The latter changed in 1861 when he was appointed First State Clerk of the Canton of Zurich. The appointment was preceded by the publication of the little banner of the seven upright people , a story in which he expressed his “satisfaction with the conditions of the fatherland”, but at the same time pointed out certain dangers associated with social progress.

Gottfried Keller's political office occupied him for ten years. It was not until the last third of his term of office that anything new appeared from him (the Seven Legends and The People of Seldwyla, part two). In 1876 he resigned to work as a freelance writer again. A number of other narrative works were created (the Zurich novellas , the final version of Green Heinrich , the cycle of novels Das Sinngedicht and the socially critical novel Martin Salander ).

Gottfried Keller ended his life as a successful writer. His lyrics inspired a large number of musicians to set music. With his novellas Romeo and Juliet in the village and dresses make the man , he had created masterpieces of German-language storytelling . Even during his lifetime he was considered one of the most important representatives of the epoch of bourgeois realism .

life and work

Parents and childhood

Gottfried Keller's parents were the master turner Johann Rudolf Keller (1791–1824) and his wife Elisabeth, b. Scheuchzer (1787–1864), both from Glattfelden in the north of the canton of Zurich . Rudolf Keller, the son of a cooper , had returned to his home village after a craft apprenticeship and several years of wandering through Austria and Germany and had courted the daughter of the local country doctor. The Scheuchzer family was largely related to the Zurich patrician dynasty of the same name , which produced doctors several times, including the universally learned doctor and natural scientist Johann Jakob Scheuchzer in the 17th century .

After the marriage in 1817, the couple settled in Zurich in the house "Zum golden Winkel", where Gottfried was born as the second child. Soon thereafter, Keller's father bought the house "Zur Sichel". Sister Regula was born here in 1822 , the only one of five other Gottfried siblings who did not die in early childhood. The poet described this house and the people who populated it in his novel The Green Henry . In general, "the actual childhood" of his novelist, the "green" Heinrich Lee, is not invented, but "even the anecdotal in it, as good as true".

Keller's father was part of the liberal movement , which mobilized against the restorative policies of the old urban elites in Switzerland and advocated a more centralized form of government. As a patriot and citizen, Rudolf Keller took part in the military exercises of Salomon Landolt's sniper corps; as a cosmopolitan craftsman, he felt a connection with Germany, adored Friedrich Schiller and participated in enthusiastic performances of Schiller’s dramas. In 1823 he was elected chairman of the wood turner's guild. He was also on the board of a school in which children from poor families were taught free of charge according to the method of the Zurich pedagogue Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi . Keller's parents professed their support for the Evangelical Reformed Church , which did not prevent the father from criticizing the religious instruction of the Zurich clergy. In this context he is attested as an impressive speaker. He died of pulmonary tuberculosis in 1824 at the age of 33 . He found his final resting place in the Sihlfeld cemetery .

The widow Elisabeth Keller managed to save the house and initially also the business. In 1826 she married the manager of her workshop, but after a few months he fell out with her and left her. After that, she and her two children lived extremely limited from the income from the house and her work in it. The final dissolution of their marriage could not be achieved until 1834, after the Liberals seized power in 1831 and, in the course of regeneration, carried out the separation of state and church and abolished the ecclesiastical matrimonial jurisdiction, which made the divorce of only formally existing marriages easier.

School days 1825–1834

According to his father's wish, Gottfried attended the school for the poor from the age of six to twelve, followed by two years at a secondary school, the “country boys' institute”, where French and Italian were also taught. He learned without difficulty and at an early age showed the need to express himself by painting and writing. He made his first attempts at writing in 1832/1833 with short stories about nature. From his boyhood, in addition to imaginative watercolor paintings, there are also a few small theater pieces that he, inspired by performances by guest traveling stages, wrote for his playmates and performed with them.

At Easter 1833 he was accepted into the newly founded cantonal industrial school, which had several highly qualified teachers in the natural sciences and literature. His teacher in geography and history was the German geologist and politician Julius Froebel , who later became the young poet's sponsor and first publisher. His French teacher, the Zurich clergyman Johann Schulthess (1798–1871), whose lessons he particularly valued, introduced him to French writers, including Voltaire , and - in French translation - with Don Quixote , a work that was one of Keller's favorite books for life .

He was torn out of this environment the following year. He had taken part in a parade organized by older schoolchildren following the pattern of coups that were frequent in politically turbulent Switzerland at the time . In front of the house of an educationally unskilled and politically unpopular teacher - he belonged to the ruling liberal party, while the sons of conservative townspeople set the tone in the cantonal industrial school - there were noisy scenes. When a commission investigated the incident, the real culprits spoke up and named Gottfried as the ringleader. The headmaster, Johann Ludwig Meyer (1782-1852), church councilor and former marriage judge, who was prejudiced against Keller, took their word for it and formulated the request: "Gottfried Keller has been expelled from school and the supervisory commission has to report this to his mother." it was assumed that the almost fifteen-year-old was barred from further school education.

Professional goal painter 1834–1842

Given the choice of career, Gottfried Keller let himself be determined by memories of his childhood painting exercises and fresh impressions at one of the annual Zurich painting exhibitions. Despite the concerns of his mother and her advisors, he decided to paint landscapes . The summer after the school mishap he spent in the picturesque Glattfelden, where he was a frequent holiday guest in the large family of his uncle and guardian, the doctor Heinrich Scheuchzer (1786-1856). In the book collection of Scheuchzer's house he found the letters about landscape painting by the Zurich painter and poet Salomon Gessner , a reading that confirmed his newfound self-esteem as an artist. Of this election, Keller wrote in 1876:

- “At a very early age, when I was fifteen, I turned to art; as far as I can judge, because half the child seemed more colorful and funnier, apart from the fact that it was a professionally determined activity. Because to become an 'artist' was, if badly recommended, at least civilly permissible. "

Years of apprenticeship in Zurich

Unfortunately for Keller, his first teacher, who ran a factory in Zurich for the production of colored vedute , was a botch. Like the “swindler” of Green Heinrich, he seems to have been happy to let the apprentice go his own way after teaching him a superficial and faulty drawing technique. In the novel, Keller reports how he appeared late for work after spending winter nights reading and, on summer days, roamed the forests of his homeland, sketching and dreaming, more and more dissatisfied with his skills. But it was during this time that he wrote his first novels, “The Outlaw” and “The Suicide”. It was not until the summer of 1837, at the age of eighteen, that he met the watercolorist Rudolf Meyer (1803–1857), known as Heinrich “Römer” in the green , who had traveled to France and Italy. He taught his student to see artistically for the first time and accustomed him to strict discipline when drawing and painting from nature. However, this “real master” suffered from delusions and broke off his stay in Zurich the following spring.

Meyer also encouraged his pupil to read Homer and Ariost , a seed for which the field was much better prepared: The young lending library and antiquarian specialist Keller already had the works of Jean Paul (“three times twelve volumes”) and Goethe (“forty For days ") devoured. In addition to drawings, his study books from 1836–1840 increasingly contain written entries: reading fruits, attempts at storytelling, drafts for dramas, descriptions of landscapes and reflections on religion, nature and art in the style of Jean Paul. A poem reminiscent of Heinrich Heine laments the death of a young girl in May 1838, whose peculiarity and fate are later poetically refined in the portrait of Anna, the childhood sweetheart of the green Heinrich Lee.

In 1839 Keller first showed which political party he felt he belonged to. At that time the dispute between the radical-liberal Zurich government and its rural electorate escalated, although they listened to their pastors on matters of faith. The government had dared to call the left Hegelian theologian David Friedrich Strauss to the University of Zurich. In the “ ostrich trade ” that followed, the conservative opposition seized the opportunity and on September 6th led thousands of armed farmers to Zurich. Thereupon Keller hurried from Glattfelden "without enjoying anything, to the distant capital to support his threatened government". What he experienced is not known. The “ Züriputsch ” was bloodily suppressed, but the liberal government also fell, and the conservatives began to rule for several years.

In Munich

In 1840 the almost twenty-one year old came into possession of a small inheritance and realized his plan to continue his education at the Royal Academy of Arts in Munich. In early summer he moved to the art metropolis and university town that had flourished under Ludwig I and attracted painters, architects, craftsmen of all kinds and students from all over the German-speaking area, including many young Swiss. Keller promised their lively intercountry life . conversely, they liked the short, bespectacled, sometimes dreamily withdrawn, sometimes full of ideas compatriot, wrapped in a black cycling coat, so much that they chose him to be the editor of their weekly pub newspaper .

Like many of the young painters who flocked to Munich, Keller never became an apprentice at the academy, where landscape painting was not yet represented as a subject, but instead worked on landscape compositions among artist friends. Munich was expensive. Since selling pictures was out of the question at first, Keller tried to stretch what he had brought with him by making do with one meal a day. Then he fell ill with typhus . Doctor and nursing staff made additional demands on his resources; so the inheritance was soon used up. Keller went into debt and had to ask his mother for support, which she repeatedly gave him, most recently with borrowed money. A picture painted by Keller with high hopes for the art exhibition in Zurich, today honored under the title Heroic Landscape , arrived there damaged, was hardly noticed and remained unsold. In the fall of 1842, hardship forced the painter to break off his stay in Munich. Most recently he had to sell a large part of his work to a second-hand dealer in order to acquire the means to travel home.

From painter to poet 1842–1848

In the hope of completing some larger work and being able to return to Munich with the proceeds, Keller rented a small studio in Zurich. But he spent the winter of 1842/1843 less painting than reading and writing. For the first time, he thought of processing his failure literarily:

- “All sorts of hardship and the worry I caused my mother with no good goal in sight occupied my thoughts and my conscience until the brooding turned into the resolution to write a sad little novel about the tragic breakdown of one young artist career, on which mother and son perished. This was, to my knowledge, the first conscious literary resolution I made, and I was about twenty-three years old. I had the image of an elegiac-lyrical book with cheerful episodes and a cypress-dark ending where everything was buried. In the meantime, my mother tirelessly cooked the soup on her stove so that I could eat when I came home from my strange workshop. "

More than a decade would pass before the completion of the Green Heinrich .

The poet

First Gottfried Keller discovered and tested his talent as a poet . It was awakened by the poems of a living person by Georg Herwegh , the "iron lark" of Vormärz . This collection of political songs, published in Zurich in 1841, aroused related but very unique tones in him, which he put into verse from the summer of 1843. It emerged nature and love poems to classic romantic pattern mixed with political songs in praise of popular liberty against tyranny and human bondage. On July 11, 1843, Keller wrote in his diary: “I just have a great urge to write poetry. Why shouldn't I try what's wrong? Better to know than to secretly consider me a tremendous genius and neglect the other. ”A little later he sent his former teacher Julius Froebel, now Herwegh's publisher, a few poems for assessment. Froebel recognized the poetic talent and recommended Keller to Adolf Ludwig Follen , a former fraternity member and participant in the Wartburg Festival of 1818, who, persecuted as a demagogue in Germany , had lived in Switzerland since 1822 and had married a wealthy Swiss woman.

Since the liberal turnaround of 1831, opponents of the European princely rule were willingly accepted in the liberally governed cantons and found professional and political opportunities to act. The brisk influx from Germany meant that the teaching staff at the University of Zurich, which was founded in 1833, initially consisted mainly of oppositional German academics. Under the founding rector Lorenz Oken , the chemist Carl Löwig , the physician Jakob Henle , the theologian and orientalist Ferdinand Hitzig , the political journalist Wilhelm Schulz and, for a few months, his friend, the natural scientist and poet Georg Büchner, who died early in Zurich , taught there alongside Fröbel . Many of them frequented Follen's house "zum Sonnenbühl", where the liberals, scattered by the ostrich trade and the Zurich coup, gradually gathered again and met with exiles of various stripes and nationalities, including the anarchist Michail Bakunin and the early communist Wilhelm Weitling .

In 1841 Fröbel co-founded the Literarisches Comptoir Zürich und Winterthur , a publishing house that soon developed into the organ of German "censorship refugees". Some of them lived temporarily in Zurich on the wanderings of their exile, such as the philosophical-political journalist Arnold Ruge and, in addition to Georg Herwegh, also Ferdinand Freiligrath and Hoffmann von Fallersleben . According to Keller, Hoffmann was the real discoverer when, after looking at the manuscript that had landed at Follen, he had the poet fetched for him. Follen, who wrote poetry himself, became Keller's mentor and revised his verses - not to their advantage. A first selection of Keller's poems appeared under the title Songs of an autodidact in the German paperback published by Froebel for the year 1845 , a second with twenty-seven love songs , idyllic fire and thoughts of a buried alive in the next volume from 1846, the last of the series. Edited again by Follen, the entire collection was published by CF Winter in 1846 under the book title Poems in the Heidelberg publishing house . The evening song to nature was the prelude :

Wrap me in your green blankets

and lull me with songs!

When the time is right, you may wake me up

With a young day's glow!

I felt tired in you,

My eyes are dull from your splendor;

Now my only desire is

to rest in a dream through your night.

The irregular

These collections - and all those that followed - also contained a song with which Keller once again made a political statement, this time visible from afar. The Sonderbund War of 1847, which resulted in the expulsion of the Jesuits and the constitution of the modern Swiss federal state , was already casting its shadow, and the “naughty lyricist”, as he later described himself, wrote the song for an illustrated leaflet in early 1844 with the refrain “They are coming, the Jesuits!”.

In 1876, Keller wrote:

- “The pathos of party passion was a main artery of my poetry and my heart really pounded when I chanted the angry verses. The first product printed in a newspaper was a Jesuit song, but it fared badly; for a conservative neighbor who was sitting in our room when the paper was taken to the amazement of the women spat on it while reading the grayish verses and ran away. Other things of this kind followed, victorious chants about won election battles, complaints about unfavorable events, calls for popular assemblies, invectives against opposing party leaders, and the like. s. w., and unfortunately it cannot be denied that only this rough side of my productions quickly earned me friends, patrons and a certain small reputation. Nevertheless, I still do not complain today that it was the call of living time that woke me up and decided my direction in life. "

In 1844 and 1845, the poet took part in the two Zurich free marches to Lucerne , from which he returned safely due to lack of contact with the enemy. He later processed this experience in the novella Frau Regel Amrain and her youngest . He was also involved in a literary dispute: Ruge and his follower Karl Heinzen had attacked Follen as a reactionary because of his belief in God and immortality and badly slandered Wilhelm Schulz, who stood up for him. Schulz, a former lieutenant in Greater Hesse, challenged Ruge to a duel and made Keller his second. Ruge evaded the demand, but Keller seconded his friend poetically with sonnets . Echoes of the “Zurich atheism controversy” can be found, heavily veiled, in the green Heinrich .

During these years, Keller was on friendly terms with the Freiligrath family and the Schulz couple, as well as the choirmaster and composer Wilhelm Baumgartner , who introduced him to romantic music through his piano playing and set a number of his poems to music. In Freiligrath's house (in Meienberg ob Rapperswil ) he met his sister-in-law Marie Melos and fell in love with her without declaring his love for her. He did this to another pretty and witty young lady, Luise Rieter , in a much-quoted love letter, but received a basket from her: “He has very small, short legs, what a shame! Because his head would not be bad, the extraordinarily high forehead is particularly distinctive, ”wrote Luise to her mother. Keller confided his lovesickness to the diary:

- “When Baumgartner was playing, I wished I could play and sing beautifully because of the Louise R. My poor poetry disappeared and shrank before my inner eyes. I despaired of myself as I often do. I don't know what to blame; but it always seems to me that my earnings are too low to bind an excellent woman. Maybe this comes from the little effort my products make for me. Rigorous studies, even if I don't need them immediately, would perhaps give me more salary and security. A heart alone is no longer valid today. "

Outwardly, the situation of the almost thirty-year-old was hardly better than after his return from Munich. The first fee was used up, the first fame as a poet drowned out; there was no livelihood to be earned with literary and art-critical articles, such as those he wrote for the Neue Zürcher Zeitung and the Blätter für literary entertainment ; He was neither made for the journalism that supported the knowledgeable Schulz, nor a merchant like Freiligrath, who had already found a job in London in 1846 and had moved there with his family. The politically committed Keller was particularly pained that he was excluded from participating in the state restructuring of Switzerland, which was carried out after the Sonderbund was overthrown in 1847-48, due to a lack of previous education. The work of the founders of the modern federal state, Jonas Furrer and Alfred Escher , whom he knew from an internship at the Zurich State Chancellery, met him with great respect:

- “I owe these men a lot of thanks in secret. From a vague revolutionary and vigilante à tout prix, I trained myself to be a conscious and level-headed person who knows how to honor the salvation of beautiful and marble-solid form in political matters and who has clarity with energy, the greatest possible gentleness and patience for the moment waits, wants to know connected with courage and fire. "

“Strict studies”, “marble-solid form” - which the autodidact Keller urgently required, was an opportunity to catch up on the education he had missed and thus to give his life a firmer footing. All of this did not remain hidden from the discerning in his environment. So the project was born to get him out of the predicament. Two patrons from the Follen district, Professors Löwig and Hitzig, won the Zurich government under Escher to grant Keller a scholarship for an educational trip. In preparation, he was supposed to spend a year at a German university.

State scholarship in Heidelberg 1848–1850

- “What is going on is monstrous: Vienna, Berlin, Paris back and forth, only Petersburg is missing. However immeasurable everything is: how deliberate, calm, how truly we poor little Swiss can watch the spectacle down from the mountains! How delicate and politically refined was our entire Jesuit war in all its phases against these admittedly colossal, but ABC-like tremors! "

This was Keller's impression in March 1848. In October of the revolutionary year he traveled via Basel and Strasbourg to politically troubled Baden and moved to Heidelberg University . Here he studied history, law, literature, anthropology and philosophy. He heard lectures by Häusser and Mittermaier , both prominent liberals and heavily involved in politics, so that the hoped-for introduction to history, law and political science did not take place for the scholarship holder. He attended the lectures on Spinoza , German literary history and aesthetics of the young Hermann Hettner , who soon became his friend, with greater profit . Keller also owed significant suggestions to the physician Jakob Henle , whom he knew from Zurich. He heard from him that anthropological college that is processed in the Green Heinrich . In 1881, Keller set a literary monument in his late work Das Sinngedicht with the story of Regine Henle's first wife, Elise Egloff .

Heidelberg was also a city of art. Keller joined the painter Bernhard Fries , son of a Heidelberg art collector, and was a frequent guest of Christian Koester , who had experienced the heyday of the literary and picturesque Heidelberg romanticism and worked as a restorer of Boisserée's painting collection. Koester, a Goethe admirer, introduced his visitors to works of old German painting and graphics and inspired him to write the poem Melancholie , which contains an interpretation of Dürer's famous copperplate engraving.

In the "Waldhorn", the house of the liberal politician and scholar Christian Kapp , Keller met the philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach , who, relieved of his teaching post in Erlangen, had been invited by revolutionary students to Heidelberg and was there in the town hall in front of a mixed group of workers, citizens and academics Audience lectured on the essence of religion. Keller about Feuerbach to his friend Baumgartner:

- "The strangest thing that has happened to me here is that I, with Feuerbach, whom I, the simple-minded lout, had also attacked a little in a review of Ruge's works, about which, roughly not long ago, I also started Handel with you, that I am with this same Feuerbach almost every evening, drink beer and listen to his words. […] The world is a republic, he says, and it cannot endure an absolute or a constitutional God (rationalists). For the time being I cannot resist this appeal. My God had long been just a kind of president or first consul who didn't enjoy much respect, I had to depose him. But I can't swear that my world won't elect a head of the Reich again one fine morning. Immortality is a purchase. As beautiful and sensitive as the thought is - turn your hand in the right way, and the opposite is just as poignant and profound. For me at least, it was a very solemn and thoughtful hour as I began to get used to the thought of true death. I can assure you that you will pull yourself together and not just become a worse person. "

Feuerbach's “turn to this world” is a central theme of the Green Heinrich .

To Johanna Kapp , the artistically gifted daughter Christian Kapp, painting student of Bernhard Fries and going to follow this to Munich, summed up the basement a deep affection. When he confessed his love to her in the fall of 1849, she confided in him that she was secretly in a relationship with Feuerbach. Some of Keller's most beautiful new poems are about this love accident, including the verses on the Heidelberg Old Bridge .

The trio of friends Keller, Schulz, Freiligrath - one of them now a member of the Frankfurt National Assembly , the other co-editor of the Neue Rheinische Zeitung - had met again at the turn of the year 1848/49 in Darmstadt , Schulz's constituency. In May 1849, Keller was an eyewitness to the retreat fighting of the Baden revolutionaries in Heidelberg . In the summer he had not attended any lectures and had fully lived his literary work: grappling with the classics of the drama , having discussions with Hettner about the dramatic theory, which a little later resulted in an intensive correspondence, and wrote Therese on various comedies and a tragedy , Pieces that have all remained fragments. At the end of the year, he published the first of a series of detailed reviews of short stories by the Swiss poet Jeremias Gotthelf , who, after liberal beginnings, was increasingly inclined to conservatism in the Blätter für literary entertainment . An introductory chapter on Green Heinrich , which was later rejected , was also created in Heidelberg. With his scholarship donors, Keller agreed not to go on one of the trips to the Orient, which were popular at the time, but to continue working on his plays in Berlin . He hoped to establish himself as a playwright on the renowned theaters of the Prussian capital. In the days of his parting with Johanna Kapp, in December 1849, he wrote to the Braunschweig publisher Eduard Vieweg for the first time and, before he left for Berlin, signed contracts with him for an edition of his poems and his novel.

Freelance writer in Berlin 1850–1855

Keller set foot on Prussian soil, traveling down the Rhine by ship, for the first time in Cologne . There Freiligrath, the ex-editor of Neue Rheinische , who was beset by court proceedings , did not miss the opportunity to celebrate his friend in a lively group. The poet Wolfgang Müller von Königswinter and, a little later in the art city of Düsseldorf , the painter Johann Peter Hasenclever were also in attendance . At the end of April 1850, Keller reached Berlin and, under the suspicious gaze of the Hinckeldey police, moved into an apartment close to the Gendarmenmarkt within sight of the Royal Theater .

The one year he wanted to spend in the city turned into five: the most productive, but also the most deprived of his life. In the last year of his stay in Berlin, he described Berlin as a “correctional institution” which “completely performed the service of a Pennsylvania cell prison”. There he wrote the Green Heinrich in agonizing work, often interrupted for months, and then put the novellas of the first volume of the People of Seldwyla on paper "in one happy move" . Two of the hopes with which he had come to Berlin, however, remained unfulfilled: The writing gave him no livelihood and his plays did not grow beyond drafts.

Experience with the theater

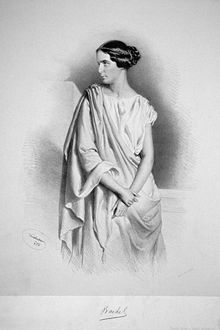

Keller was disappointed with his "main school", the Royal Theater. He probably liked the ambience and the delicate women's pile - "I would soon dare to head a respectable cleaning shop with the help of the precise studies that I undertake in the interim files on bonnets and ruffs of all kinds". He also wanted to see plays that he already knew on stage for the first time, classic by Shakespeare , Goethe , Schiller and modern by Hebbel . But he complained about the lack of artistic direction , especially with Hamlet and Maria Magdalena . He developed his critical views on the dramaturgy in correspondence with Hettner, who processed them in his book The Modern Drama in 1852 . With the demand for a distanced, reflective audience that "sees through perfectly the poignant contrasts of a situation that are still hidden from the people involved," the budding epic poet anticipated a principle of epic theater . When Élisa Rachel Félix made a guest appearance in Berlin in 1850 with dramas by Corneille and Racine , her renunciation of theatrical pathos and her art of emphasizing the poet's words convinced him of the value of these pieces and of the untenability of the prejudice against them that Lessing had instilled in the Germans classic French tragedy. The performance of Christine Enghaus from Munich in the title role of Hebbels Judith also made a deep impression on him.

Incidentally, Keller saw the tragic art of acting in decline, whereas the comic art was on the rise. He attended the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Urban and the king Municipal Theater , where the Berlin local farces of David Kalisch and Viennese popular comedies were given pieces that allowed the actors, from the impromptu weave biting political remarks and then the censorship to undermine. He felt vividly how "the poor people and the self-desperate Philistine find satisfaction for the injustice done". There is also "more aristophanic spirit " in the couplets than in the educated bourgeois comedies of contemporaries. People and art, it seemed to him, were striving here with united forces for a farce of a “nobler nature”, a new form of high comedy, for which the time was of course not yet ripe - views that were difficult to reconcile with the intentions of the poet , diligently delivering plays and thus generating a regular income.

Literary conviviality

The same was true of Keller's way of avoiding theater people and fellow writers: “By staying away from all the leading circles, he cut himself off from any kind of sponsorship by others,” says Baechtold, citing Keller's urge for independence and his contempt for as the cause Cotery . Keller was reluctant to present himself as a writer . That made him unsuitable for the kind of sociability that was cultivated in the traditional salons and literary associations of the capital: “In winter I frequented a few circles, e.g. B. Fanny Lewald's , but found the goings-on and behavior of the people so unpleasant and trivial that I soon stayed away again. ”A theater writer friend recommended him to Bettina von Arnim and implored him“ to do violence to himself this time and in the highest person of the famous woman to pay your respects ”, - Keller did not go. The poet Christian Friedrich Scherenberg , with whom he got on well at times, took him to a meeting of the tunnel over the Spree - Keller did not appear a second time. In the case of Karl August Varnhagen von Ense , the “grand old man” of the classical-romantic epoch, who had already written encouraging comments about his poems in 1846, he excused his absence by saying that he “needed all the form for traffic in northern Germany”. In fact, he initially stuck to compatriots, southern Germans and Rhinelander, who met in Berlin wine and beer bars, among them the natural scientist Christian Heußer and the sculptor Hermann Heidel .

"Time brings roses, May 2nd, 1854"

But from 1854, after the first three volumes of the Green Heinrich had appeared and Keller had acquired a tailcoat , the obligatory item of clothing for high society, he took part in the coffee companies that Varnhagen's niece Ludmilla Assing organized in the same rooms at Mauerstraße 36, where Rahel Levin , Varnhagen's late wife, had invited to social evenings thirty years earlier . In addition to the writers Max Ring , Adolf Stahr , Alexander von Sternberg and Eduard Vehse , Keller also met the former Prussian Minister of War Ernst von Pfuel , friend of Heinrich von Kleist , the sculptor Elisabet Ney and the singer Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient , which gave him the opportunity " to grind down a bit and acquire a more flexible tone ”. His hosts held him and his Green Heinrich in high regard. Varnhagen gave him Rachel's hand copy of Johannes Scheffler's Cherubinian Wanderer as a present. Keller wrote to Hettner about Ludmilla Assing:

- “Ludmilla declared herself as hell for me and, since she paints in pastel, already portrayed me. I share this honor with Herr von Sternberg, Vehse, Ring, etc., who all hang on Ludmilla's wall, and the better half of this painted company are some pretty girls' faces. "

Also during his last two years in Berlin, Keller was often a guest at the house of the publisher Franz Duncker and his wife Lina nee. Tendering at Johannisstrasse 11 (Gräflich Rossisches Palais), since 1855 at Potsdamer Strasse 20 and around 1877 at von-der-Heydt-Strasse. In this circle were mostly younger, democratically minded artists and writers. So the journalist Julius Rodenberg and the painter Ludwig Pietsch . From the latter comes the following memory of the poet:

- “In his original Swiss coarseness, the small, broad-shouldered, stocky, iron-solid, taciturn, bearded man with the beautiful, serious and fiery dark eyes under the mighty forehead, who, however, when something or someone annoyed him, did not just express his opinion very openly , but was also always ready to give her more emphasis with his strong fists, a very peculiar figure among the polished Berlin people. He made no secret of the fact that he didn't think too much of them. "

In Duncker's house, Keller also met Betty Tendering , Lina Duncker's sister, and fell passionately in love with the elegant, tall and beautiful twenty-two-year-old. She went under the name Dorothea Schönfund (= B ella T rovata = B etty T endering) in the last volume of the Green Heinrich . Like his hero in a novel, Keller did not dare to confess his love to the unattainable. Instead, to bring relief to his broken heart, he started brawls with bystanders on his way home at night, incidents which the remark about Keller's fists alluded to and which resulted in a black eye and a fine. In the novel the target of the attack is a rough country boy, in Berlin it was a writer.

Not only about worn-out Berlin literary figures, but also about poets who insisted on their Brandenburg, Pomeranian, Old Prussian down-to-earthness, Keller judged angrily and spoke of "emotional iron eater" at Scherenberg, Goltz , Nienberg and Alexis : "All these northern and Prussian regions behave, as if no one but them had felt, believed or sung anything ”. He excluded one from the Scherenberg area: the actor and reciter Emil Palleske , whose art he admired. When Palleske came to Switzerland on a tour in 1875, Keller introduced him to the Zurich audience. He later renewed his acquaintance with other members of the Berlin literary and art scene, but he remained on friendly terms with only two women: Ludmilla Assing and Lina Duncker. For a long time he directed content and humorous letters to her. Ludmilla Assing, who stayed in Zurich several times on her transit to Italy, advised him in the process of the Varnhagen diaries published in Zurich and banned in Prussia, and corresponded with her until 1873.

Living conditions, publications, concepts

In 1851 Keller published the Newer Poems from Heidelberg in Braunschweig's Vieweg Verlag , of which there was an increased edition in 1854. Between 1851 and 1854 Keller made several contributions to the Blätter für literary entertainment , including three further extensive reviews of Gotthelf's novels, his main literary critical work (→ s: Keller about Jeremias Gotthelf ). Since he no longer had a scholarship available from 1852 and Vieweg's fees and advances were barely enough for board and lodging in expensive Berlin, he was forced to run into debt again, just at the time when his supporters and friends in Zurich were expecting reports of success from him . "I sincerely ask not to despair of myself etc.", he called out to them. In July 1853, he described to Hettner his circumstances while working on the Green Heinrich :

- “The confused web of lack of money, little worries, a thousand embarrassments, in which I carelessly got entangled when I entered Germany, repeatedly throws me back into inactivity; the effort to appear decent and honest at least to the daily environment always suppresses the concern for the more distant; and the constant excitement which one has to hide, these thousand pinpricks absorb all external productivity, while the feeling and the knowledge of the human gain in depth and intensity. I wouldn't let those last three years later be bought. So my things move forward with marvelous slowness, which you, as an active and hardworking man, can only understand if you know the details. "

There was also internal resistance, as Keller's demands on the quality of his writing had grown in the same proportion as the length of the novel:

- “If I could rewrite the book again, I now wanted to make something permanent and effective out of it. There is a great deal of intolerable ornamentation and flatness, and also great defects of form; To see all of this before it was published, to have to write on it with this mixed awareness, while the printed volumes had been around for a long time, was a purgatory that should not benefit everyone nowadays. "

At this point the publication of the first three volumes of the novel was already foreseeable. When they were sent out at the end of 1853, the worst was still to come for Keller: the year and a half until the end of the fourth volume, in which he undertook to recount the unhappy love of his novel hero, synchronized with his own painful experiences. On Palm Sunday 1855 he wrote the last chapter - "literally in tears". In May the fourth volume was finally in the bookstores.

For the publisher Eduard Vieweg , too , Der Grüne Heinrich had become a test of nerves: for five years he had been unable to persuade his author to deliver manuscripts at the promised time, either through threats or enticements. Vieweg considered the novel "a masterpiece". Nevertheless he paid the author the fee of a beginner: “If the sheet of this book is not worth 1½ Louis d'or , while things that are a thousand times worse are paid for with 4 and 6 Louis d'or, that means reduce my work and step under the feet, ”he complained. All in all, Vieweg paid barely 1 d'Louis d'or per sheet, while his publishing house was flourishing and although he was aware of Keller's economic situation. An exchange of letters ensued between Berlin and Braunschweig, which, because of the cutting bitter tone - while always being polite - is unparalleled in German literary history. Jonas Fränkel, the editor of Keller's letters to Vieweg, ruled:

- “Vieweg was not magnanimous enough to look forward to the finished book and only to commemorate the work of the countless days and nights that was enclosed in the 1700 printed pages. That the publisher sometimes has to make a sacrifice to the author, just as the author makes a sacrifice for his work, this insight was alien to him. For him […] Der Grüne Heinrich also meant nothing but a commodity whose value is determined by the business books. He made a strange statement, and the wages that the author received at the end of six years were not even enough to pay the accrued debt to the carpenter. "

Keller also remained unpaid - probably lifelong - for the intensive activity with which he filled his extended breaks in writing: reading classics, which added the depth dimension valued as “literariness” to the fonts, and mentally spinning out new works. Paradox that for him both work and relaxation were at the same time; plausible that this was another reason for the "fabulous slowness" of his progression. Parallel to the work on the Green Heinrich , those life images were created in Keller's head that were reflected in short stories after the conclusion of the novel: The people of Seldwyla . In a few months he completed the first five stories of this cycle, Pankraz, der Schmoller , Frau Regel Amrain and her youngest , Romeo and Juliet in the village , The three just comb makers and Spiegel, the kitten . Vieweg did not bring it out until the following year, after various quarrels. The second volume remained unfinished. Another narrative with the working title “Galathea”, which includes the later inventory of the Seven Legends and the epitome , was so clearly in view of Keller in Berlin that, in need of money and seduced by the rapid writing of the five Seldwyler stories, he signed a contract with Franz Duncker concluded, who obliged him to deliver the manuscripts in the course of 1856. He sold Vieweg the unwritten second volume of the People of Seldwyla and even arranged contractual penalties with him in the event of delay. In vain: The Seven Legends made 16, the people of Seldwyla II 19, the epiphany 25 years in coming. Another larger work, the verse epic Der Apotheker von Chamouny or the little Romanzero , an answer to Heine's return to belief in God and immortality, was completed by Keller in 1853, but only published in the Gesammelte Gedichte - 30 years later.

Although appealed to by the city's water-rich surroundings and a frequent stroll in the zoo , Keller never felt at home in Berlin. In the last two years he has been increasingly drawn back to Switzerland, especially since his mother and sister, whom he had often left without news for a long time, were eagerly awaiting him there. What kept him in Berlin were his debts and the hope of ultimately being able to start a business by writing. There was no lack of initiative from the Zurich government to accommodate him in a good way. In 1854 he was offered a teaching position at the newly founded Polytechnic, today's ETH Zurich . After a brief hesitation, he declined, “because teaching poets in the true sense of the word was never a long one”, and recommended Hettner, who, however, accepted a call to the Dresden Art Academy . Private people from Zurich, alarmed by his return home friend Christian Heußer, also took care of him. Jakob Dubs , his colleague from the days of the free crowd marches and now the Swiss National Council , initiated the establishment of a small stock corporation to save Gottfried Keller from the guilty prison . But the sum of 1,800 francs that came together was not enough. Keller's lovesickness finally triumphed over the futile hopes: "I can no longer take it in Berlin," he wrote to his mother and revealed his situation to her. Elisabeth Keller, who had sold her house on Rindermarkt in 1852, did not hesitate and set off her son a second time. At the end of November 1855 he left Berlin, stopped off at Hettner in Dresden , met Berthold Auerbach and Karl Gutzkow there, and returned to his hometown in December after seven years abroad.

Freelance writer in Zurich 1855–1861

Little bothered by the great powers, the Swiss federal state was established during Keller's stay in Germany. On his return, the poet found his homeland in full economic and cultural boom. The Alfred Escher era had dawned, and liberal Zurich laid the foundations of its current status. The expansion of the national railway network and the founding of the Schweizerische Kreditanstalt drew capital into the country, and the Polytechnic, temporarily under one roof with the university, attracted scientists from all faculties. The unbroken tradition of liberal asylum policy also ensured the influx of talented refugees from Germany, Austria, France and Italy.

Acquaintances

Most of these immigrants were poor like Richard Wagner , but some were also wealthy, such as the married couple François and Eliza Wille and Otto and Mathilde Wesendonck , whose generous hospitality gave rise to a form of salon life - new for Zurich. Keller shortly after his return:

- “Here in Zurich I have been doing well so far, I have the best company and I see all kinds of people who are not so nice together in Berlin. A Rhenish family Wesendonck is also here, originally from Düsseldorf, but they were in New York for a while. She is a very pretty woman named Mathilde Luckemeier, and these people are making an elegant house, they are also building a splendid villa near the city, they have given me a friendly welcome. Then there is in an elegant Councilor fine suppers where Richard Wagner, Semper , who built the Dresden theater and museum, the Tübingen Vischer and some Zurich come together and where one morning 2:00 to genugsamem reveling hot cup gets tea and a Havana cigar. Wagner himself sometimes serves a solid lunch table, which is bravely poketed. "

Keller got on "remarkably well" with Wagner, whose writings he had already studied in Heidelberg. Wagner valued the people of Seldwyla , who had finally appeared in the spring of 1856, praised by Auerbach, rebuked by Gutzkow; Keller called Wagner's Ring des Nibelungen a “treasure of original national poetry” and a “fiery and blooming poetry”, the latter with reservations; because in the face of verses like “Weia! Waga! Woge, you wave, walle to the cradle! ”He later judged rather harshly about Wagner:“ His language, as poetic and magnificent as his grip on the German prehistoric world and his intentions are, is unsuitable in its archaic frenzy, the consciousness of the present or even to dress the future, but it belongs to the past. "

He told his friend Hettner about other attractions his hometown had to offer:

- “Every Thursday there are academic lectures à la Sing-Akademie zu Berlin , in the largest hall in the city, where women and men crowd hundreds of times and endure around two hours incessantly. Semper gave a very lovable and profound lecture on the essence of jewelry. Vischer will make the decision with Macbeth . In addition, there are a number of special cycles of the individual sizes, so that every evening you can see the maids running around with the large wardrobe lights to illuminate the innerly enlightened ladies also outwardly. Of course, it is also rumored that the brittle and bigoted Zurich women discovered a very respectable and innocent rendezvous system in these lectures and that their thoughts are not always concentrated on the lecture. "

The "individual sizes" meant Jacob Burckhardt , Hermann Köchly , Pompejus Bolley and Jakob Moleschott , all German except Burckhardt. It was "terrible", he confessed to Ludmilla Assing, "how Zurich is teeming with scholars and writers". You hear almost more standard German, French and Italian than Swiss German. “But let's not let it get us down; The national festival life has already started again with the first days of spring and will continue to exist until autumn ”.

The festival poet

The national character that the annual celebrations of the shooting, singing and gymnastics clubs had assumed over the course of the century rubbed off on typical events such as exhibitions and the opening of new railway lines. At the same time, the open-mindedness demonstrated at such festivals gave Swiss patriotism a touch of cosmopolitanism . The political asylum seekers did not remain onlookers, their participation in “free popular life” was a matter of course, their contributions welcome. Wagner's activities electrified the music and theater scene, virtuosos and greats of the art of acting appeared, in 1856 Franz Liszt , 1857 Eduard Devrient . Literary tourists rushed to marvel at the republican miracle, such as the aged Varnhagen with Ludmilla, the Dunckers and the Stahr - Lewald couple from Berlin, the Hettners from Dresden. Paul Heyse came from Munich and immediately made friends with Keller.

The poet immersed himself in this "festival life", dreamed up in the Green Heinrich during the Berlin privations:

In the fatherland lavender

There the joy is sinless,

And I better not go home

I won't be any worse that way!

Meanwhile, the novellas he had promised his publishers remained unwritten. Almost the entire literary production of this period of life revolves around celebrations: opening chants, marching and goblet songs, the verse epic Ein Festzug in Zürich , the poem Ufenau for the commemoration of Ulrich von Hutten's grave , set to music and performed by friend Baumgartner as a choir; In 1859 the prologue for the centenary of Schiller's birthday and in 1860/61 on the occasion of the inauguration of the Schiller monument in Lake Lucerne, the essay Am Mythenstein , in which he criticized Wagner's language, but also took up his criticism of traditional theater and developed ideas for Swiss national festivals . Some of this was implemented, but only towards the end of the century. On the other hand, Das Fähnlein der Seven Upright ( The Flag of the Seven Upright) had an immediate and strong effect , a novella centered on a fictional ceremonial speech, given at a historical festival, the Aarau Federal Free Shooting of 1849. The author put it in the mouth of a young shooter who added Keller's view Relationship between love of the fatherland and cosmopolitanism is clad in the often-quoted word: "Respect every man's fatherland, but love yours." The story, published in Auerbach's German People's Calendar in 1860 , expressed Keller's "satisfaction with the conditions of the fatherland" and was enthusiastically reprinted in Switzerland.

Keller now had a name as a poet and storyteller. But his economic situation remained precarious: he would not have been able to live without the free board and lodging with his mother, to whose housekeeping Regula Keller also contributed through her earnings as a saleswoman. At the beginning of 1860 he was so desperate that he - unsuccessfully - offered his publishers the broken-down little Romanzero , although he felt the inconvenience of such a publication: Heine had died in 1856 and all kinds of dubious obituaries romped about on the book market. "If it were allowed," he wrote to Freiligrath, "to beat the believers instead of paying them, I would burn the cursed poem with a thousand joys."

The political publicist

What prevented Keller from making professional use of his skills during these years was the discrepancy between his idea of civic effectiveness - the educational goal of the novel The Green Henry - and the absurd role of a republican court poet , which he threatened to grow into. For the second time in his life, like after returning from Munich, he felt from the participation of government relations excluded more painful now that he's freischärlerische overcome past novella and its reflections resigned over political responsibility, impartiality and state in the novel would have.

Under these circumstances, plans by Hettner and Müller von Königswinter to make him secretary of the Kölnischer Kunstverein only interested him weakly. He spoke up all the more energetically in politics, especially since the great powers were now beginning to harass the young federal state. At the end of 1856, during the Neuchâtel trade , he had already joined the cross-party popular movement to ward off a Prussian invasion and sent an encouraging address to the High Federal Assembly in an editorial . Politically, it was no different from many such announcements. His “call for the electoral assembly in Uster ” in autumn 1860 during the Savoy trade was different: Keller exposed himself as the leader of an initiative for the upcoming national council election and attacked the “lack of independence” of the previous Zurich MPs, who were - mostly civil servants - Followers of the " Princeps " Alfred Escher acted who, in the opinion of Keller and his colleagues, were determined to resist Napoleon III's disregard for Swiss neutrality . had missed. In the Bernese Confederation , he continued these attacks in witty articles. At the same time, the little flag was reprinted in the features section , which read: "Let guys with many millions emerge who have a lust for political domination, and you will see what mischief they do!" The irritation in the Escher camp was considerable. Had a snake been fed on the breast? Although none of their men got through the election initiative, the spell was broken, against the " Escher System " and its political articles of faith, economic power and industrial progress, the voice of a writer rose for the first time. The attacked man saw that too and was heard a little later in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, which was close to him . His tone was cool and superior, his subject was respect for Switzerland and its neutrality:

- “Just as the single individual can only be viewed as independent if he is able to secure his livelihood through his own hands, so the more sources of income it can tap into and the more abundantly it knows how to let them flow, the more independent a people becomes To take a stand and be able to assert. "

Keller, who saw this as a swipe at his ongoing economic dependency, immediately countered in the Zürcher Intellektivenblatt :

- “If you wanted to give an outrageous [exaggerated] answer to this position, which is a little proud of money, you could say: There are poor cantons in Switzerland that are nevertheless very venerable. For example, there was also a single individual named Pestalozzi , who was in need of money all his life, did not understand at all about the acquisition and nevertheless made a great impact in the world, and for whom the expression that he deserves no respect would not have been quite right . "

In the spring of 1861 he published further "marginal glosses" in which he expressed his dissatisfaction with conditions on the periphery of Escher's "system". The last of these articles dealt with a central point: the Zurich Grand Council had tried to legally reduce child labor in cotton mills from 13 to 12 hours, but failed because of resistance from the manufacturers. Keller wrote:

- “[The state] calculates that perhaps the thirteenth hour, recurring three hundred times a year, is the hour too long that could save the freshness of life, and it begs the cotton for this single hour. […] But the cotton 'niggelet' [shakes] its head constantly, the course sheet of the present in its hand, referring to 'personal freedom', while it knows that the state is in the ecclesiastical, educational and police departments sanitary facilities often enough to restrict this unconditional personal freedom, and that the source from which this power flows cannot dry up. She will nag her head until the state will one day pull together its rights and perhaps cut away not just an hour but every thirteen hours for the children. Then Matthäi would be at the last and the end of the world. "

A nationwide ban on child labor came into force in Switzerland in 1877. The consequences for the author of the series of articles became apparent after a few months. A high-ranking politician in the Escher camp, Franz Hagenbuch , Keller's and Wagner's supporter, drew up a seemingly daring plan for placing the poet in the civil service. It succeeded and was received half angrily, half approvingly as a "stroke of genius" in public.

First State Clerk of the Canton of Zurich 1861–1876

On September 11, 1861, Keller applied to Hagenbuch's urgent advice for the vacant position of the first state clerk of the canton of Zurich . Three days later he was elected by the government by five to three votes. He got the highest-paid office that his home republic had to assign. The passage, "neither a half nor a full sinecure ", left him little time for his literary work, but corresponded to his inclination and his abilities and freed him from constant economic worries. “Nobody complains about this turning point in the poet's life! It actually became his salvation. Because it was on the next path to wilderness, ”comments Baechtold.

Taking office and political activity

After Keller was appointed, the press began to guess what reason he was chosen over his competitors, experienced lawyers and administrators? Did you want to shut up a Frondeur with an annual salary of 5,000 to 6,000 francs ? Even papers that rejected this suspicion were surprised and expressed doubts about the ability of the poet. The skepticism seemed justified when Keller slept through the hour he took office on 23 September and had to be picked up by Hagenbuch personally. The previous evening he had taken part in a large party at the “Zum Schwan” inn, at which local and foreign Garibaldians , including Ludmilla Assing , Countess Hatzfeldt , Emma and Georg Herwegh and Wilhelm Rustow , celebrated Ferdinand Lassalle , who was passing through . When the latter held a séance at a late hour , with Herwegh serving as his medium , Keller woke up from sitting in silence, grabbed a chair and insisted on the two of them with the words "Now it's too fat for me, you rag, you crook!" In the ensuing turmoil he was put out in the fresh air. The government reprimanded Keller. Six weeks later, the newcomer at the head of the State Chancellery was so well integrated that the Zürcher Freitag newspaper , which had distinguished itself by criticizing his appointment, saw reason to congratulate him.

Keller moved with his mother and sister into the Zurich "Steinhaus", where the office was on the first floor and the official residence of the state clerk on the second. Unlike her counterpart in the Green Heinrich , the poet's mother had the satisfaction of seeing her son honored and cared for. Elisabeth Keller died on February 5, 1864, at the age of seventy-seven, without having been sick.

One of Keller's diverse official duties was the drafting of so-called prayer mandates . The first of these documents was written in 1862. The government had reservations about publishing it. The author, who himself stayed away from the church celebrations, had, as usual, wished the state church well-attended services on the day of prayer, but then added: “But let the non-church-minded citizen, using his freedom of conscience, not go through this day in restless distraction, but To prove his respect for the fatherland in a quiet gathering. ” To have to read these words of a Feuerbachian from the pulpit would have been an imposition for many clergy, which is why the government ordered a diplomatic mandate from another clerk.

Outside of his official business, Keller worked from 1863-65 as secretary of the Swiss Central Committee for Poland, a political-humanitarian aid organization that he had started when the January uprising in Poland broke out . He also represented his home district of Bülach in the Grand Council from 1861-66 , but was no longer elected because he was now being attacked by the emerging Democratic Party as an advocate of the system that he had sharply criticized before his appointment.

Dissatisfaction with the " Escher System " was articulated from 1863 onwards in the demand for direct democracy . As a proponent of representative democracy , Keller took a position against a total revision of the Zurich constitution in several newspaper articles in 1864/65 and participated in a partial reform in the following year, which gave voters the right to demand the drafting of a new constitution by popular initiative . The Democrats soon made use of this right to overthrow the system. Bad harvests, a crisis in the Swiss textile industry and a cholera epidemic in Zurich favored her project. The upheaval was initiated by the pamphlets of the Zurich attorney Friedrich Locher (1820–1911), which seriously damaged the reputation of Escher and some of his followers with a mixture of truth and lies. Anger and excitement take hold of broad strata of the people. The movement reached its peak at the end of 1867, but after Locher was eliminated, it quickly turned into constructive trajectories.

In less than a year a constitutional council was elected - with Keller as the second secretary - and a new constitution was drawn up, which was adopted by a large majority on April 18, 1869, with a high turnout. The Democrats also won the first direct election of the Zurich government shortly thereafter: all but one of the councils of the old liberal guard were replaced. Keller expected to be released. "We had a dry revolution in our canton by means of a very peaceful, but very malicious referendum, as a result of which our constitution is now being totally changed," he had already confided in his pen pal Assing in 1868; and further:

- “Since I am one of those who are not convinced of the usefulness and wholesomeness of the matter, I will walk away completely resigned, without resenting the people who will find their way around again. In the beginning of the movement we were in eternal trouble because it was started by infamous slander. But the people, who were forced to believe the lies in their boldness, should have been made of stone if they shouldn't have been excited. The slanderers are also already recognized and set aside; but as the world goes, His Majesty the Sovereign nevertheless benefits from the cause and retains his booty, which he calls extended popular rights. "

To Keller's surprise, the new government confirmed him in office. He served her for another seven years in less politically turbulent times.

Failed marriage plans, honors, new friends

Gottfried Keller fell passionately in love with Betty Tendering in the winter of 1854/55, but she did not return his love. The same happened to him in 1847 with Luise Rieter from Winterthur and with Johanna Kapp from Heidelberg. At the beginning of 1865 Gottfried Keller met the pianist Luise Scheidegger (1843–1866) in the house of a friend from Zurich. She lived in Herzogenbuchsee , where she grew up as a foster child with well-to-do relatives and obtained a concert diploma from the Geneva Conservatory . In May 1866 he became engaged to her without public announcement. A few weeks later, Luise committed suicide in her home town. There is no certainty about the motive. Luise was described as "helpful, pleasant to deal with, witty and in her appearance of great loveliness". "Noticeable cheerfulness, marked by a slight melancholy, gave her a special nobility in addition to the already existing facilities." What is certain is that the young musician felt drawn to the poet; It can also be assumed that she was no longer able to cope with the marriage with the politician involved in relentless party struggles when she was told by well-intentioned people what his new and old enemies said of him: drunkenness, bullying and godlessness. In conflict with herself and with her surroundings, urged to break the promise given, suicide may have appeared to her as the only way out. - Keller mourned Luise Scheidegger for seven years. Then he proposed marriage to the daughter of the room, Lina Weißert (1851–1910). He did not know that she was already in a relationship with the lawyer Eugen Huber . Lina politely and coolly rejected the request of the now fifty-three year old.

The Zurich singers' associations, student associations and, last but not least, the cantonal government used July 19, 1869 to “remind the silent poet of his destiny” on the occasion of his fiftieth birthday. The law faculty of the University of Zurich awarded him an honorary doctorate. At the banquet, Keller met the young Viennese legal scholar Adolf Exner , with whom he immediately developed a warm friendship. In 1872 he met his amiable sister Marie , who married the Austrian urologist Anton von Frisch in 1874 . Keller's correspondence with Adolf Exner and Marie, which continued until shortly before his death, shows him at the height of his art as a letter writer. For the sake of "Exnerei", Keller took two vacations in Austria after ten years without a vacation. At the Mondsee he even began to paint again. Karl Dilthey wrote to Marie Exner in 1873: “Keller is so thoroughly lonely, and Exnerei and I are pretty much the only people he can take.” The person suffering from his constant celibacy characterized himself as follows: “I am [...] a fat little guy who goes to the inn at 9 o'clock in the evening and goes to bed at midnight as an old bachelor. "

Literary production

Keller's poetic drive was not stunted under the pressure of official business. Opposite the Viennese literary critic Emil Kuh , he characterized his mode of production:

- “My laziness, about which you wrote indulgently, is a very strange pathological reluctance to work with regard to litteris. When I'm at it, I can work through large pieces in a row, day and night. But I often shy away for weeks, months, or years from taking the bow I have started from its hiding place and placing it on the table; it is as if I feared this simple first manipulation, I am annoyed about it and still cannot help it. Meanwhile, however, is the senses and ruminate constantly, and as I aushecke new, I may be just the broken set to continue the old, if the paper is but safely back. "

In addition to the newly acquired correspondent Kuh, his old friend Friedrich Theodor Vischer , meanwhile a professor in Tübingen, also made a critical contribution to the fact that Keller continued the stories he had started in Berlin. In terms of publishing, this was done by Ferdinand Weibert (1841–1926), the new owner of the Göschen'sche publishing house . The Seven Legends appeared there in 1872, the second edition one year later. Keller used the fee to buy back Vieweg's publishing rights. He transferred it to Weibert, who in 1873 brought out a new edition of The People of Seldwyla . In 1874 five more Seldwyler novels followed: Clothes make the man , The smith of his luck , The misused love letters , Dietegen and The lost laugh . The impetus for the story of the tailor Wenzel Strapinski, who in Clothes Make People is mistaken for a Polish count, the poet owed to his work in the Central Committee for Poland and his connection with the Polish émigré Władysław Plater . The historical references are even stronger in Lost Lach , a roman clef condensed into a novella . In it, Keller targeted the excesses of the democratic agitation of 1867/68 and the reformatory zeal of some liberal theologians . The latter caused a stir in Zurich; the author was preached in St. Peter . In Germany, the novellas saw three editions in quick succession. Keller realized that his pen would be able to feed him from now on - as a state clerk he was not entitled to a pension. So he resigned his office in July 1876 in order to devote himself fully to writing. In that year he moved into an apartment in Bürgli , where he resided until 1882.

The old work 1876–1890

With the exception of the dramas, Keller carried out all of the work ideas that he had received in Berlin in the decade and a half up to his death. He also wrote another cycle of novels and a novel. Just as he made new friendships at his age, surprisingly new things also emerged in the field of poetry.

From 1876–77, Keller wrote the Zurich novellas , some of which were preprinted in Julius Rodenberg's Deutscher Rundschau , and then came out in their final form as a book by Göschen. The book edition includes the stories Hadlaub , Der Narr auf Manegg , Der Landvogt von Greifensee , The Fähnlein der Seven Upright and Ursula .

The completely reworked Green Heinrich was also published by Göschen from 1879 to 1880, and in 1881 as a preprint in the Deutsche Rundschau the cycle Das Sinngedicht with the novellas From a Foolish Virgin , The Poor Baroness , Regine , The Ghost Seers , Don Correa and The Berlocken . For the book edition of the poem (1882), Keller switched to Wilhelm Hertz , who had bought up the fiction department of the Duncker publishing house.

In 1883 Hertz Keller published Gesammelte Gedichte . In 1886 the novel Martin Salander appeared in sequels in the Deutsche Rundschau and at the end of the same year as a book by Hertz. From 1889 Hertz, who had acquired Weibert's rights to the final version of Green Heinrich , brought out Keller's collected works . From 1877, Keller exchanged letters with the Husum poet Theodor Storm and his friend, the Schleswig government councilor Wilhelm Petersen. In 1884 Arnold Böcklin settled in Zurich. Painter and poet formed a friendship that lasted until Keller's death. Böcklin designed the frontispiece for Hertz's complete edition, as well as the medal that the Zurich government had minted for his 70th birthday and presented him in gold.

Gottfried Keller had written a autobiography, which was kept in the meantime by Professor and Privatdozent for German literature Julius Stiefel (1847-1908).

Regula Keller died in 1888. Gottfried Keller died on July 15, 1890. After a funeral service on July 18, he was cremated in the Zurich crematorium, which he had campaigned to build. Keller's ashes found their final resting place in the central cemetery in Zurich in 1901 near his grave monument designed by Richard Kissling (today Sihlfeld cemetery ).

He bequeathed his estate to the Zurich Central Library , which was then the city library. This includes Keller's manuscripts and letters, his library and over 60 drawings and paintings by hand.

Painting by Karl Stauffer-Bern , 1886

Phototype based on

Arnold Böcklin's template,

frontispiece to Volume 9 of the Collected Works , 1889

Works: Book publications by year of publication

- 1846: poems

- 1851: Newer poems

- 1854–55: The Green Heinrich , first version of the novel

- Vol. 1. Vieweg, Braunschweig 1854 ( digitized and full text in the German text archive )

- Vol. 2. Vieweg, Braunschweig 1854. ( digitized and full text in the German text archive )

- Vol. 3. Vieweg, Braunschweig 1854. ( digitized and full text in the German text archive )

- Vol. 4. Vieweg, Braunschweig 1855. ( digitized and full text in the German text archive )

- 1856: The people of Seldwyla , part I of the novella cycle ( digitized and full text in the German text archive )

with the stories: Pankraz, der Schmoller | Romeo and Juliet in the village | Mrs. Regel Amrain and her youngest child | The three righteous comb-makers | Mirror, the kitten. A fairy tale - 1860: The flag of the seven upright ones

- 1872: Seven legends , cycle of novels ( digitized and full text in the German text archive )

- 1873–74: The people of Seldwyla , Part I of the cycle unchanged, Part II with the stories:

Clothes make the man | The smith of his fortune | The abused love letters | Dietegen | The lost laugh - 1877: Zurich novels , cycle of novels with the stories:

Hadlaub | The fool on Manegg | The bailiff of Greifensee | The flag of the seven upright | Ursula - 1879–80: The green Heinrich , final version of the novel

- 1881: The epitome , cycle of novels ( digitized and full text in the German text archive )

with the stories: From a foolish virgin | Regine | The poor baroness | The ghost seers | Don Correa | The curls - 1883: collected poems

- 1886: Martin Salander , Roman

- 1889: Collected works in ten volumes

Awards

- 1869 honorary doctorate from the University of Zurich

- 1878 honorary citizenship of the city of Zurich

- Honorary membership in the Zurich Dramatic Society

- Gottfried Keller is shown on the 10-franc note of the fifth series (1956-1976).

Effects

Outside of Switzerland, Keller was almost forgotten in the German-speaking area until the beginning of the Second Empire . Its impact began with the inclusion of Romeo and Juliet in the village in the Deutsche Novellenschatz published by Hermann Kurz and Paul Heyse . When the Züricher Novellen appeared in the Deutsche Rundschau in 1877 , Heyse, then a favorite of the German reading public, published a sonnet in which he apostrophized Keller as “Shakespeare the novella”. In Menschliches Allzumenschliches 1879 Friedrich Nietzsche counted The People of Seldwyla to the “treasure of German prose ” and to the books that “deserve to be read again and again”.

Testimonials from writers

In the two decades after Keller's death, under the influence of Baechtold's biography and the ten-volume complete edition that was repeatedly reprinted, articles on Keller increased in features and specialist literary journals. In the transition from naturalism to neo-romanticism , movements which Keller had been reserved about, followers of both directions were attracted to him. In 1904 Ricarda Huch concluded her basement essay with an enthusiastic phone call:

- “A while with us! The time is still far away when people give your name to a lonely constellation that now stands over the warring earth with a funny wink, now in blissful beauty. Be still our teachers and guardians! Defend us when we stray from the strict path of truth, shake us when we sink into ourselves weak and cowardly, show us with your pure eyes the golden abundance of the world. Teach us, above all, to hate vanity, lies, selfishness and pettiness, but also to love the slightest thing, provided it has an unadulterated life, and to worship the divine childlike and masculine, with hatred and love to keep the eternal order of relationships in mind. "

In 1906, Hugo von Hofmannsthal gave a fictional artist talk about the "incomprehensibly fine and reliable description of mixed conditions" at Keller:

- “Once you've read your way into it, you have a sense of unbelievable transitions from the ridiculous to the poignant, from the snotty, disgustingly silly to the nostalgic. I don't think anyone painted the embarrassment like him, in all its tones, including the ultraviolet ones, which one usually doesn't see. Just remember the incomparable letters he has stupid, distracted people compose. Or the characters of swindlers and swindlers. "

Thomas Mann's first acquaintance with Keller's work also fell during these years : “[Last summer] I took heart in Bad Tölz and read the old man from A to Z. Since then I have wholeheartedly endorsed his fame. What imagery! What a flowing narrative genius! "

In 1919 - and not just in Zurich - Keller's 100th birthday was celebrated. Two new Nobel Prize winners for literature spoke up , Gerhart Hauptmann (“Keller's art is essentially youthful”) and Carl Spitteler (“No superfluous tone or decorative word ”). Thomas Mann, future recipient of this award, wrote:

- “I read, as he himself, according to Green Heinrich , read Goethe for the first time as a young man: everything in one go, enchanted, without even having to stop inwardly. Since then I have often returned with love for the individual, and 'I never want to conquer this love', as Platen says. "

Elias Canetti had to endure the anniversary at fourteen as part of a Zurich school celebration and angrily vowed never to become a “local celebrity”. In his 1977 memory book, he commemorates his oath with the words:

- "But I still had no idea with what delight I would read the Green Heinrich one day , and when I, a student and again in Vienna, fell for Gogol with skin and hair, it seemed to me in German literature, as far as I knew it at that time, a single story like his: The three just Kammacher . If I were lucky enough to be alive in 2019 and had the honor of standing in the preacher's church for his bicentenary and celebrating him with a speech, I would find very different eulogies for him, even the ignorant arrogance of one Fourteen-year-olds would defeat. "

In 1927 Walter Benjamin honored Fränkel's critical complete edition with an essay. In it he wrote of Keller's prose:

- “The sweet, heart-strengthening skepticism that matures when you look closely, and how a strong aroma of people and things takes hold of the loving viewer, has never entered a prose as in Keller. It is inseparable from the vision of happiness that this prose has realized. In it - and that is the secret science of the epic poet, who alone makes happiness communicable - every tiny cell of the world weighs as much as the rest of all reality. The hand that thundered open in the tavern never lost its weight in the weight of the most delicate things. "

In the same year, Hermann Hesse commented on the new edition of Keller's early poems:

- “Among these poems there are extraordinarily beautiful ones, one of which one cannot understand that they could lie there unnoticed and unprinted for decades! But Keller's poetry is hardly known at all, it is rougher and more idiosyncratic than his prose. You could see it buried recently at the first performances of Lebendig , Othmar Schoeck wrote sublime music for this cycle of poems, but the majority of the audience did not know these wonderful poems and sat across from them, embarrassed and shaking their heads. Perhaps it is the same with these youthful poems unearthed by Fränkel. But it would be a shame. "