History of the city of Zurich

The city of Zurich already existed as a Turicum in Roman times, but only rose to the ranks of the larger Swiss cities in the Middle Ages. The rulers of the Holy Roman Empire chose the city on the Limmat as the location for two important spiritual foundations around the places of worship of the city patrons Felix and Regula , which shaped Zurich: The Grossmünster - and the Fraumünsterstift .

In 1262, the privilege of imperial immediacy secured the imperceptible rule of a distant German king. Zurich's entry into various leagues - including the emerging Confederation in 1351 and the Constance Confederation in 1385 - protected the city in the long term from the expansionist desires of local aristocratic families, especially the Habsburgs . Together with Bern , Zurich, as a suburb, determined the politics of the emerging confederation of the Confederation.

Since Ulrich Zwingli's Reformation , Zurich has been one of the spiritual centers of the Reformed Confession . The status of “Rome on the Limmat” resulted in Zurich seeing itself as a sovereign city-republic since 1648 on the same level as Venice . In the 18th century, however, Zurich was more like “Athens on the Limmat”, thanks to many scholars such as Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi , Johann Kaspar Lavater and Johann Jakob Bodmer as well as its important position as a trading city.

Only after massive external pressure did the dominated landscape gradually achieve equality with the establishment of the Canton of Zurich . Zurich has been the economic and financial center of Switzerland since the 19th century .

Name, coat of arms, seal

Main article: Coat of arms of the canton and the city of Zurich

The oldest evidence of the name Zurich in its Latin form comes from the 2nd century AD and can be read on a tombstone that was found in 1747 on the Lindenhof in Zurich. On this stone, the name STA {TIONIS} TURICEN {SIS} indicates a Roman customs station Turicum . The origin of the name is not finally clear, but it is in any case pre-Latin. The most likely derivation * Turīcon from the Celtic personal name Tūros .

The well-known early medieval Latin forms of the name for Zurich are Turigum (807), T (h) uregum and Thuricum (898). The first evidence of a German form of name, namely Ziurichi, appears in the 7th century with the geographer of Ravenna ; later there are spellings like Zurih (857) and Zurich (924). In the Zurich German dialect, the city is called Züri [ˈt͡sʏrɪ] . The name Tigurum , used mainly in the 17th and 18th centuries, was a contemporary creation and was intended to refer to the Tigurines , a sub-tribe of the Helvetii .

The first known seals of the city council of Zurich hang on two documents from 1225 and 1230. They carry the legend sigillum consilii thuricensium and carry the two city saints Felix and Regula from the Theban Legion . They carry their heads, which are surrounded by a nimbus , in their hands . From 1348 onwards, Exuperantius , the servant of Felix and Regula, joined the city seal. The definitive inscription of this seal is sigillum civium thuricensium . The municipality of Zurich has had the obliquely divided shield in its seal since 1798 , overlaid by a wall crown , with one or two lions as shield holders.

The city's coat of arms, the shield divided diagonally by silver and blue, is documented for the first time on a seal of the Zurich court from 1389. The flag, which is still in use today, has only been reliably documented since 1434. On the coins and cityscapes of Zurich, the city's coat of arms was originally crowned by the imperial coat of arms and the imperial crown. The heraldic shield has been held by two lions since the 15th century. Sometimes the lions hold a blue and white banner, one of which shows the three city saints. Around 1700, the imperial coat of arms and crown were removed, while the lions remained as shield holders. The lion became the Zurich heraldic animal as "Zürileu" . The current coat of arms of the city shows the diagonally divided shield, elevated by a wall crown, with two lions as shield holders.

The city of Zurich was both a royal and a ducal mint. The oldest documented mention of the mint dates back to 972, the oldest coin is a Carolingian denarius with the inscription LUDOVICUS REX, RS. HADTUREGUM. King Henry III also granted the Fraumünster Abbey the right to mint in the 11th century. Your coin ban encompassed the Zürichgau and the area around the Walensee to Sargans, Central Switzerland to the Gotthard, the Aargau to Huttwil and the Thurgau to the Mur. The coins that were minted in Zurich have various symbols and inscriptions. The Fraumünster Abbey only minted pfennigs, which were initially square, then round after 1400. In 1524 the abbey's right to mint was transferred to the city. This had already confirmed the right to mint to King Sigmund in 1425. From the 16th century, the city's coat of arms appeared with the imperial coat of arms on the coins, for example on the Zurich thaler and the ducat, sometimes with the two lions as shield holders. The inscription read MONETA TURICENSIS CIVITATIS IMPERIALIS. Later the coat of arms disappeared and the legend changed to MONETA REIPUBLICÆ TIGURINÆ. The Zurich shield was now held by one or two lions, the individual lion held either a sword or an orb. On the top, either views of Zurich or sayings were usually embossed, such as DOMINE CONSERVA NOS IN PACE, IUSTITIA ET CONCORDIA or PRO DEO ET PATRIA. The independent coinage of the city of Zurich ended in 1798.

antiquity

The earliest traces of human settlement activity in the area of today's city of Zurich are the remains of wetland settlements of the Egolzwiler culture (4430–4230 BC), which can be detected in the area of the western lake basin . The sites, which were also found during the later Neolithic , Bronze and Early Iron Ages up to 700 BC. Were settled, sometimes extend from the shore area up to 500 m into today's lake. Settlements have been archaeologically proven on the left bank of the lake at Alpenquai , Bauschänzli , Breitingerstrasse and Wollishofen (Haumesser, Bad) as well as on the right bank of the lake at the Kleiner and Grossen Hafner , at Utoquai and on Seehofstrasse. Most of these bank settlements sank into the lake in the Late Bronze Age, when the level rose from approx. 404 to approx. 407 m above sea level. M. rose, probably because the debris cone of the Sihl in the area of the main station dammed the lake.

During the Iron Age , settlement activity in the Zurich area shifted to terraces along the rivers and the lake. Finds and burial mounds in Riesbach (Burghölzli), and Witikon (Egglen), Höngg (Heiziholz), Altstetten (Hard), Affoltern-Seebach (Jungholz) are documented from the Hallstatt period (8th to 5th centuries). Finds and graves from the Latène period (5th to 1st century) have been found in Aussersihl (Bäckerstrasse), Enge (Gablerschulhaus), Altstetten (Hard) and Witikon. Individual and coin finds from the area of the old town date from the 1st century . In the canton of Zurich, only one central settlement from the Iron Age has been reliably documented to this day, which was located on the Uto-Kulm plateau on the Üetliberg and was protected by ramparts.

The Celtic Helvetians settled in and around Zurich, as finds at Rennweg show. Celtic oppida probably existed on the Lindenhof and on the Uetliberg . The strategically and technically favorable location as well as coin finds suggest the existence of a trading center. The Celtic settlement of about seven hectares was around the Lindenhof hill.

From the time of the Roman conquest of eastern Helvetia in 15 BC. An early Augusta military base comes from the Lindenhof, which was later joined by a civil settlement with a military station. The open market town ( vicus ) Turicum belonged to the province of Gallia Belgica after securing Roman rule, then after its foundation around 85 BC. To the province of Germania superior . Turicum was not fortified as vicus , but had a customs post of the Gallic customs ( Quadragesima Galliarum ). Goods and travelers were cleared there before entering the province of Raetia if they traveled on the Roman road between Vindonissa and Curia or on the navigable route between Lake Walen and the Rhine, and a duty of 2.5 percent was levied. The importance of Turicum is based almost exclusively on its location at the outflow of Lake Zurich, as the goods had to be reloaded here from sea to river vessels. Turicum was also not on any important Roman main road. The ancient name Turicum and the fact that there was a customs post there is only passed down thanks to the grave inscription for Urbicus, son of the local customs chief, which was found in 1747 on the Lindenhof. The port was probably also important, as at that time goods could probably be carried on boats to Walenstadt . The Roman town was at the foot of the Lindenhof , a central hill, on an island between the rivers Sihl and Limmat or Lake Zurich.

To date only a few archaeological traces of Roman Zurich have been excavated. Among them are the remains of a thermal bath (Thermengasse), graves and traces of handicraft businesses, residential houses as well as objects of daily use and jewelry, but also of cult facilities, such as a round building on Storchengasse, a four god stone on the Lindenhof and a cult complex on the water church island. There were probably temples on the St. Peter Hill and the Sihlbühl , a sanctuary also stood on the Grosse Hafner , a former island in the lake. There was a bridge near today's town hall. The remains of a fort on the Lindenhof, reinforced with eight to ten towers, date from the late Roman period . Parts of the Lindenhof retaining wall also date from Roman times. Around the Roman vicus, which was inhabited by approx. 250 to 350 people, a number of manors that were laid out in the 1st century were grouped. Such systems in Albisrieden (Hochfeld / Galgenacker), Altstetten (Loogarten), Oerlikon (Irchel), Wipkingen (Waidstrasse) and Wollishofen (Gässli / Seestrasse) have been proven in the area of today's city.

The Alamanni incursions into what is now Switzerland began in AD 260 . After the imperial reform of Emperor Diocletian from 286 Turicum came to the province of Maxima Sequanorum in the prefecture of Gallia . A fort was built on the Lindenhof in the 4th century under Diocletian or Constantine I as part of the fortification of the Rhine border. The Üetliberg was also used again as an observation post and place of refuge. In 401 the fort was evacuated by the Roman troops like the whole area north of the Alps. There is no reliable information about the further fate of the Gallo-Roman population and the Turicum settlement . The vicus and the fort continued to exist on a modest scale as a Romanesque island of continuity and were gradually settled by new sections of the population of Alemannic-Franconian origin. On the basis of the archaeological findings, a destruction of the settlement structures in Zurich can be ruled out. The Roman settlement hardly changed until the early Middle Ages. Roman roads, buildings and infrastructure continued to be used. Evidence for the continuity of the resident Romanesque population and for immigration in the early Middle Ages is primarily provided by the grave fields from this period found in Zurich. a. in Aussersihl (Bäckerstrasse), at St. Peter (choir walls, St. Peter hill) and in the so-called court burial ground on Spiegelgasse / Obere Fences. These grave fields were apparently in the 11./12. Abandoned in favor of the cemeteries of St. Peter, the Grossmünster and the Fraumünster.

Early middle ages

During the immigration of the Alamanni to what is now the canton of Zurich, the fort on the Lindenhof remained . The oldest written source that refers to a Castrum Turico is a vita of Saints Felix and Regula from the late 8th century AD. In addition to the fort, this reference could also have meant the actual settlement of Zurich. In the Vita S.Galli , too, Columban's missionary journey through Alemannia in 610 leads through the castellum Turegum . The geographer of Ravenna finally includes a Ziurichi in the Latin translation from the 9th century in the index for the area of the Alamanni. The oldest written mention of Zurich can be found in a document from the St. Gallen Monastery of April 27, 806/07/09/10, which was issued in vico publico Turigo . So that doesn't mean in the fort, but probably in the rural settlement of Zurich, which was not yet walled. In the early Middle Ages and partly in the High Middle Ages, the fort remained one of the main focal points of the settlement of Zurich, as this was the seat of secular rule in the Palatinate .

After Alamannia was definitively incorporated into the Franconian Empire in 730, the area around Zurich was assigned to the eastern part of Ludwig the German during the Frankish division of the Empire . For 741/46 a first count can be found in the Carolingian Zurihgauuia . The Zurich fort formed the center of an extensive imperial estate complex that stretched from Aargau via Uri to eastern Switzerland. During this time, Christianity, which had been pushed back in the meantime but was never completely displaced from the old settlement centers, probably strengthened again. Unfortunately, in addition to archaeological finds, there are only sparse sources and a few legends from this transition period. One says that the Alemannic Duke Uotila resided on the Üetliberg and gave it its name. Another says that Charlemagne had a palace in Zurich and even resided there. Not only through a legend, but also in documents, it is documented that the East Franconian King Ludwig the German equipped an existing women's monastery in Vico Turegum with a large amount of land, immunity and its own jurisdiction on July 21, 853 with a certificate made out and sealed in Regensburg eldest daughter Hildegard . With this he founded the royal monastery of Fraumünster . The corresponding deed of foundation is the oldest deed in the possession of the Zurich State Archives. At the same time, a Carolingian palace was probably built on the basis of the Roman fortifications on the Lindenhof. The other ecclesiastical and monastic centers of the early medieval settlement of Zurich, the Grossmünster, Fraumünster and St. Peter were probably only surrounded by simple enclosures with ramparts and moats at that time. In any case, the founding of the urban settlement of Zurich in the early Middle Ages seems to go back to the Franks and not to the Alamanni.

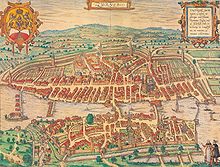

| Churches and monasteries in Zurich on the Murer map by Jos Murer from 1576 | |

| 1 preacher monastery (Dominican) | 6 Fraumünster Monastery (Benedictine Sisters) |

| 2 "Collection" of Saint Verena (Beguines) | 7 Parish Church of St. Peter |

| 3 Barefoot Monastery (Franciscans) | 8 Augustinian monastery |

| 4 Grossmünster canon monastery | 9 Oetenbach Monastery (Dominican Sisters) |

| 5 Wasserkirche | |

Probably the oldest sacred center in Zurich's old town is the chapel and later St. Peter's Church, which has been archaeologically accessible since the late 8th or early 9th century and has been documented since 857 . It crowns the southern foothills of the Lindenhof hill and thus has the most prominent place in Zurich's churches. Its district included the city on the left bank with the exception of the vicinity of the Fraumünster and the surrounding area from Kilchberg to Schlieren . The chroniclers Heinrich Brennwald and Gerold Edlibach described the St. Stephen's Church and Chapel, which is located outside the city walls (St. Annagasse) and was first mentioned in 1218, as the oldest parish church in Zurich. It was undoubtedly of early origin, but whether it really was the first church in Zurich cannot be proven. The last remains of the buildings demolished in 1528 disappeared in 1909.

Around the same time, a first convent was built near the graves of Saints Felix and Regula on the site of today's Grossmünster. According to legend, the two saints were executed on the Wasserkirchen Island and then walked headlessly up the slope to the site of the Grossmünster, where they are said to have been buried. Whether the legend is based on a true core is controversial. Around 1480, the episode added to the legend that the saints were wheeled at the site of St. Stephen. The Propstei St. Felix and Regula, known since 1322 under the name "Grossmünster", is documented only since 924/31, but probably goes back to the 8th century. The legend of Felix and Regula from this time already tells of an ancient pilgrimage, which suggests the existence of a convent near the graves. Around 870 the East Franconian King Karl III. the convent into a canon, probably at the same time as the most important relics of Felix and Regula were transferred to the church of Fraumünster Abbey, consecrated in 874. The founding legend of the Grossmünsterstift around Charlemagne thus probably refers to his great-grandson Charles III, whose presence in Zurich cannot be documented. Between the Grossmünster and Fraumünster, a "processional axis" was created between the burial place of the saints in the Grossmünster, the place of execution on the Wasserkirchen Island to the relics in the Fraumünster.

As royal foundations, the Grossmünster and the Fraumünster owned extensive lands. In addition to Albisrieden , Schwamendingen , Fluntern , Höngg , Meilen, the Grossmünsterstift held free float as far as the Rhine, the Reuss and the upper Lake Zurich. In addition to the cathedral, the Grossmünster was the most important monastery in the Diocese of Constance in the Middle Ages . Its district originally comprised the area to the right of the Limmat up to the Glatt. In addition to the property in and around the city of Zurich , the Fraumünster Abbey owned considerable land in the Urnerland , the Cham farm , the Albiswald, d. H. today's Sihlwald including the area between Horgen and Albisrieden on the eastern slope of the Albis, Langnau and the Reppischtal . His district, however, was limited to its immediate surroundings in the city. The goods of the Fraumünster Abbey and the Grossmünster Canons' Monastery around Zurich were administered by ministerials from the area: The lords of Hottingen, Mülner , Manesse , Biber, Brun, Kloten, Trostberg, Schönenwerd and the like. a. The bailiff over the imperial estate and the goods of the two monasteries was exercised by an imperial bailiff who was not subordinate to the counts of the Zürichgau but directly to the German king.

The development to the imperial city

Today archaeologists imagine the early medieval city as a place with several centers. The Fraumünster, the Grossmünster, the Peterskirche and the Palatinate were surrounded by fences and ramparts. In between the 9/10. Century an urban settlement, which was called civitas from the 10th century . The importance of the fortified Palatinate also shows, among other things, that around 940 the Disentis monastery brought its relics and books to safety from the Hungarians in Zurich. An enlargement of the Palatinate in the 11th and 12th gave impetus for urban development Century under the Ottonians and the Salians . Since the conquest by the Duke of Swabia after the Battle of Winterthur in 919 with his Palatinate, Zurich was one of the main places of the Duchy in Swabia .

The fact that rule over Zurich was claimed by various secular and spiritual powers is illustrated by the coinage. The oldest coins found that were minted in Zurich bear the name of the East Franconian King Ludwig IV , alongside King Rudolf II of Burgundy indicated his claims to rule over Zurich with corresponding coins, replaced by the Swabian dukes Hermann I to Ernst II. and the German kings from the Ottonian dynasty . King Henry III finally transferred the right to mint to the Fraumünster on the occasion of the new award of the Swabian ducal dignity around 1045. In addition to the coinage law, the customs and market law, which have existed since ancient times, distinguished Zurich as a supra-regional trading center as early as the early Middle Ages. Under the German kings and dukes of Zähringen, Zurich developed into the most important market place for central and eastern Switzerland in the 11th and 12th centuries, with trade connections to northern Italy and across the Rhine to Holland and Flanders.

The dukes of Swabia, who often stayed on the Limmat in the 10th and 11th centuries, were in direct competition with the German kings. While no royal presence in Zurich is documented for the Carolingian period, from 952 and 1027 the Ottonian and Salian kings and emperors distinguished the city with their frequent presence. First Otto I. and Heinrich II. Only in Swabian, then from 1018 by the latter for the first time in affairs of the empire. Multiple parties and found Reichstag place in the Palatinate on the Lindenhof, the Reichstag at Pentecost 1052, the Emperor Henry III. held with nobles from Lombardy , or the engagement of his son Heinrich IV. at Christmas 1055. Heinrich III. build a new building with a hall and hall in Zurich based on the example of the Palatinate in Goslar. The Palatinate Zurich moved from the role of a Swabian suburb to the role of a suburb of the empire, especially for diets in matters of the parts of Burgundy and Italy north of the Alps. In the Gesta Friderici imperatoris, Bishop Otto von Freising named Zurich nobilissimum Sueviae oppidum , i.e. the most elegant city in Swabia, looking back on this period . The inscription Nobile Turegum multarum copia rerum - Zurich, noble due to the abundance of many things, is emblazoned on its city gate . At the end of the 12th century, Zurich's important position was underlined with the construction of the first city fortifications .

In the Middle Ages, rule over the city of Zurich and the clergy was actually exercised by the German king or the Duke of Swabia. The royal rights of rule were delegated to an imperial bailiff. This lucrative office was controversial between the most distinguished noble families in the Duchy of Swabia at the time , namely the Zähringers and the Lenzburgers . Since the first half of the 11th century, the Counts of Lenzburg held the bailiwicks of Gross- and Fraumünster in hereditary possession. It was only when the Lenzburger died out in 1172 that the bailiwick finally fell to the Zähringers via Gross- and Fraumünster. With their claim to the Duchy of Swabia from 1079 onwards, they claimed complete political rule over Zurich. When the Zähringers renounced the Duchy of Swabia in favor of the Hohenstaufen, they received Zurich as a direct imperial fief from the Emperor as compensation, so that Zurich definitely came under Zähring sovereignty. With this, the Palatinate Zurich lost its important function at the interface of the tria regna , Germany, Burgundy and Italy. From then on, the Hohenstaufen rulers handled Italian affairs in Constance. Duke Berchtold IV of Zähringen , Reichsvogt of Zurich from 1173, is considered to be the founder of the Heilig-Geist-Spital on Zähringerplatz (until 1842), from which the Cantonal Hospital emerged in 1804. Berchtold V. then already held the title of castvogt and, according to one of his documents from 1210, saw himself as the owner of all sovereign rights of the empire in Zurich. As a castvogt, on the one hand the Palatinate on the Lindenhof, which was still developed by the Lenzburgers, was his official seat, on the other hand the office building "zum Loch" near the Grossmünster. In contrast to other cities under Zähring rule, Zurich did not expand as planned.

After the Zähringers died out in 1218, King Friedrich II divided the imperial bailiwick. The areas to the right of the Limmat went to the Counts of Kyburg , those to the left of the Limmat to the Barons of Eschenbach-Schnabelburg . The area of the city with the adjacent settlements Hottingen, Fluntern, Ober- and Unterstrass, Wiedikon, Aussersihl, Stadelhofen, Trichtenhausen, Zollikon, Küsnacht and Goldbach fell to the Fraumünster Abbey. Gross- and Fraumünster became imperial immediately. In 1219 Frederick II issued a document to the Fraumünster, his subjects and the citizens of Zurich, which almost inevitably also implies the imperial immediacy of the city, since he used the expression " de gremio oppidi nostri " - that is, from the "crowd of our city" spoke. With the certificate, the City Council of Zurich received formal, legal and political competencies for local self-government for the first time. Zurich became an imperial city . The office of Reichsvogte of Zurich was now limited to four, then to two years. Its task was to keep the peace and exercise the high judiciary as well as the protection of the royal property. As a rule, the imperial bailiffs were appointed from among the powerful Zurich families of the Biber, Bockli, Brun, Glarus, Manesse, Mülner or Wisso.

After 1218, the actual “city mistress” of Zurich was the respective abbess of the Fraumünster. Friedrich II combined the title of Fraumünster abbess in 1245 with the imperial prince status . Her formal competencies included the customs, market and coinage rights granted to the city or ministerial families, she appointed the mayor as head of the lower court and had a say in the election of the Reichsvogte. Until 1433 she confirmed the city constitution and temporarily represented the city externally. For the emerging urban community, it was the most important source of legitimation alongside the empire. In competition with the Fraumünster were the city's merchants, who had their own merchant rights with self-administration of their professional interests, as well as the Grossmünster, which tried to increase its political status by raising Charlemagne to founding father. Both clerical foundations, however, like the monastery of St. Gallen, did not manage to create the foundations for a late medieval territorial state in the 13th century because they neither the political and legal guardianship of their bailiffs, nor the Habsburgs from the 14th century Shake off control of the city.

In 1220 traces of a city council can be found for the first time, which has had its own seal since 1225. In addition to Felix and Regula, their servants Exuperantius were depicted on the seal. This probably stands for the council and the citizenship of Zurich, which have recently joined the Gross- and Fraumünster. The seal embodied the own legal personality of the citizenship and the city council. The inscription of the seal read " sigillum consilii et civium Thuricensium ". Various rulership rights of the Fraumünster Abbey were continuously transferred to the city council, first as a pledge and later at their disposal. This process was facilitated by the struggle between Emperor Friedrich II and the papacy. Because the ecclesiastical pens held in Rome while the citizenship followed the emperor's party, the spiritual persons and the abbess were even expelled from the city in 1247/49, which led to the consolidation of the citizenship's political position. In addition to the council, citizenship also became more important from the middle of the 13th century, so that at the turn of the 14th century the formula council and the citizens of Zurich were already being used in important legal documents.

Around 1250, with the letter of judgment, a collection of all the laws in force in Zurich at that time was created for the first time, i.e. the city law was laid down in writing. The main aim of the statute was to ensure the peace and welfare of the citizens within the city walls. For this purpose, the punishment of crimes against life and limb, measures against feuds and the powers of the council, court and police measures were regulated. Oath associations were explicitly forbidden within the citizenry, which was directed against guilds and societies. The clergy were also subjected to the judge's letter through a special " order and statute of priesthood ", although only lay people were to be tried by the city council and clergymen before a choir court of the Grossmünsterstift. The city council still consisted exclusively of knights and patricians, i. H. Citizen families eligible for advice, a mayor's office did not yet exist. In 1262 the legal position of the city was strengthened once again when the German King Richard of Cornwall not only, like his predecessors, expressly confirmed the privileges of the two religious foundations, but also at the same time expressly confirmed the freedom of citizenship. With that, Zurich definitely became an imperial city . The appropriate privileges left the city later repeated by the respective Reich leader confirm last in 1521 by Emperor Charles V .

During the interregnum 1256–1273, Zurich sought protection from Count Rudolf IV of Habsburg and joined the Rhenish League of Cities and conjured the first Swabian country peace in 1281. The independent position of the city in 1267 in the feud with the Barons of Regensberg was evident to expression. In a long guerrilla war, Zurich was able to maintain its position against the Regensbergers with the support of the Habsburgs. In 1268, among other things, the Regensberg town of Glanzenberg near Fahr Monastery and perhaps also the Üetliburg were destroyed. After Rudolf became German King in 1273, Zurich quickly became alienated from the Habsburgs, as Rudolf appointed Habsburg ministers as imperial bailiffs and collected imperial taxes in an unusual way. After Rudolf's death in 1291, Zurich therefore concluded a limited coalition with Uri and Schwyz against Habsburg. Duke Albrecht I of Austria therefore opened a feud against Zurich, from which the chronicler Johannes von Winterthur reports the following episode: The Zurichers went on a campaign against Winterthur , which turned into a real disaster. So many men had died that Zurich was left practically defenseless. Duke Albrecht I therefore tried to take Zurich and put an army in front of the city walls. In this desperate situation, the Zurich women disguised themselves as warriors and led by Hedwig from Burghalden with long spikes on the Lindenhof . The besiegers believed that a strong army had somehow got into the city and lifted the siege. In fact, Zurich took action against the Habsburg city of Winterthur in April 1292, but then had to capitulate to Albrecht I after a six-month siege. Thereafter, the knights' influence on the city council was severely restricted in favor of the Habsburg-friendly merchants, who had made up the majority in the council since 1293. As a result of the defeat, Zurich also had to give up its alliance with Uri and Schwyz, but received the Sihlwald from Albrecht, which had previously been assigned to the Lords of Eschenbach as bailiwick. Zurich then remained loyal to Habsburg for a long time and supported, among others, Duke Leopold I of Austria in the Morgarten War against the Confederation.

The legal and economic rise of the city of Zurich in the 12th century was reflected in a significant structural expansion. As visible signs of the developing urban autonomy, the first stone houses and aristocratic towers , four large monasteries of the mendicant orders of the Dominicans ( Predigerkloster , Oetenbach ), Franciscans ( Barefoot Monastery ), Augustinians in competition with the established spiritual centers of Grossmünster and Fraumünster and a first town hall at the Limmat. At the end of the 13th century, the entire city area was surrounded by the second city fortification (→ city fortification of Zurich ), as documented on the Murer map of 1576. During this time, Zurich was probably under the patronage of the Fraumünster abbess Elisabeth von Wetzikon a center of Minnesang , documented by the famous Manessische Liedersammlung , which was founded by a collection of the urban patrician family Manesse in Zurich. The Zurich aristocratic inventories of the time include five noble families in the vicinity of the city ( Zähringer , Nellenburger , Lenzburger , Kyburger, Habsburg ), around 25 noble families of baronial and more than 90 families of knightly class, the latter mainly ministerials of the clergy and secular lords of the region. Around 1300 Zurich had between 8,000 and 9,000 inhabitants. The population consisted of «city nobles», i. H. ministerials and knights resident in the city, "burgers", d. H. Distance merchants directly from the empire and middle-class families who became wealthy, as well as artisans and serfs with almost no rights. A special group was made up of around 200-300 Jews, Cawertschen and Lombards (southern French and Italian moneylenders), some of whom had achieved prosperity through the credit system and money trading, but had no political rights.

The economic and demographic development of Zurich reached its first peak in the 13th and 14th centuries. Zurich was one of the most important market places in Upper Germany with trade connections to Northern Italy and across the Rhine to Lower Germany. The Zurich coins and masses were decisive between the Upper Rhine and the Alps and the city had developed its own textile industry. Woolen goods, linen fabrics and processed silk products were widely exported. The expression or consequence of this growing economic power was the growing Jewish and Lombard minority who made the credit, which is important for trade, available. The result of this development was the increasing cultural importance of Zurich, as wealthy families promoted art creation, and an initially peaceful territorial expansion through systematic purchases of land and rights along the trade routes. A prerequisite for this flourishing was a good understanding with the regionally important noble families, especially the Habsburgs, and the supra-regional imperial power.

The Brunsche guild constitution and membership of the Confederation 1336–1400

As in many cities, in Zurich in the 14th century the tension between the economically up-and-coming artisans without rights and the politically decisive old knight and middle-class families erupted in a political revolution. In 1336 the craftsmen rose up under the leadership of the knight Rudolf Brun and with the financial support of the richest Zurich citizen Gottfried Mülner and drove the previous city council from power. In the First Jury Letter on July 16, 1336, Brun presented a new constitution for Zurich based on the model of the Strasbourg oath, which was confirmed in 1337 by the Wittelsbach Emperor Ludwig IV (→ Brunsche Zunftverfassungs ): the craftsmen were organized in 13 newly founded guilds , the knighthood and the money aristocracy in the so-called Konstaffel . From then on, the 26-member city council consisted of 13 representatives each from the guilds and the Konstaffel, who were reappointed every six months. At the center of the new order was the office of mayor, elected for life, who also received extensive powers in appointing city councils and to whom the citizens had to swear obedience. The main result of the so-called Zurich guild revolution was, in addition to the approval of the craft guilds, the rise of Rudolf Bruns to the temporary sole ruler of Zurich. The constitution created by Brun remained in force until 1798, despite several revisions to the jury's letter.

The deposed councilors and their families were banned from the city, but with the support of the Counts of Rapperswil organized the resistance against Brun and the new Zurich constitution. Rudolf Brun meanwhile rallied the townspeople behind him by agitation against the local Jews , who were obliged to grant loans to the citizens in the letter of judgment. On February 24, 1349, all male Jews in Zurich were killed in a pogrom . They were likely locked in a house that was then set on fire. Women and children survived and fled. The synagogue on today's Froschaugasse was destroyed. The property of the Jews was shared by the city and the king, and all debts of the citizens to the Jews were canceled. However, Jews soon settled again in Zurich. In 1436 the council decided to finally expel the Jews. In 1350, a coup d'état by the opposition against Brun on the city failed, the night of murder in Zurich .

In view of increasing foreign policy difficulties, Brun finally sought support from the Habsburgs . However, the destruction and plundering of the city of Rapperswil by Brun prompted Duke Albrecht II to take action against Zurich, as he was the patron and a relative of the Rapperswil Count Johann II from the House of Habsburg-Laufenburg . In this situation Brun looked for an alliance with the four forest sites, which were politically isolated at the time . On May 1, 1351, the citizens of Zurich swore an everlasting alliance with the Swiss Confederation . The main burden in the war with Duke Albrecht II of Habsburg was nevertheless borne by Zurich. In 1351, 1352 and 1354 the city was unsuccessfully besieged by Habsburg troops. A peace between Zurich and Habsburg was not reached until 1355. Brun proved to be a ruthless tactician, because he made the peace without involving the confederates.

After Brun's death in 1360, his successors continued his territorial policy. In the 15th century, Zurich finally benefited from the opposition between the Luxembourgers and the Habsburgs in the empire. Several rulers from the House of Luxembourg gave Zurich important sovereign rights in order to strengthen the city against the Habsburgs. In 1353, under Brun, it was still possible to obtain the imperial privilege that Zurich could no longer be summoned to foreign courts. Another important step was the transfer of a whole series of imperial rights by Emperor Karl IV. In 1362 and 1365. Among other things, the Emperor Zurich left Lake Zurich to Hurden, including fishing and shipping rights, the right to the inheritance of the Rapperswil counts, and the right to include noble lords of the countryside in the Zurich castle law, and the very important authorization to collect and re-occupy imperial fiefs that have become unmarried within a radius of three miles. This made it possible to bring the surrounding areas of the former Imperial Bailiwick of Zurich under the suzerainty of the city. Due to the alliance with the Swiss Confederation, Zurich repeatedly took an anti-Habsburg position, for example in the Sempach War of 1386–1388. In 1400 King Wenzel granted the city council the right to elect the imperial bailiff as chairman of the blood court himself and exempted Zurich from imperial tax. In 1415 he was exempted from the imperial and regional court, and in 1431 he was granted the privilege of conferring blood jurisdiction in his territory himself. Emperor Sigismund finally crowned this privilege in 1433 with the right to pass enactments of any kind in the last instance and with the granting of feudal sovereignty over the imperial fiefs of Kyburg, Regensberg and Grüningen. Thus the city became de facto independent in their domain through imperial privileges through clever tactics between the Luxembourgers, Habsburgs and the Confederation.

As a result of the clashes between the Confederation and Habsburg, clashes broke out in the city between supporters of both sides. The federally-minded guilds obtained a series of resolutions, the second jury letter of 1393, to break the power of the Habsburg-friendly city nobles and merchants. Since that time, Zurich has been governed by two councils, the “Little” and the “Big” Council (also known as the Council of Two Hundred) made up of representatives of the guilds, the city nobles and the merchants. The members of both councils were in fact elected for life and complemented themselves through co-optation . Zurich thus became a “guild aristocracy”. The price of Brun's policy was the collapse of Zurich's long-distance trade and the silk industry. This anti-trade and craft-friendly trend was confirmed by the political disempowerment of the previously dominant merchants.

Development of the city-state up to the Reformation

Main article : Territorial development of Zurich

The final turn away from Habsburg and the securing of the predominance of the craft guilds led to a decline in the export industry and trade. The old council, ruled by merchants, had tried to bring as large a stretch as possible under Zurich control from the trade route leading from western Switzerland and from Basel up the Limmat to Zurich and from there via Chur to Italy. The guilds, on the other hand, wanted to dominate the largest possible hinterland around the city, which could take up part of the production of the city's guilds and ensure the city's supply of raw materials and grain. At the end of the 14th century, however, the city had only a few direct rulers outside the city, especially along Lake Zurich and in the Limmat Valley. These properties were the result of a sometimes accidental acquisition policy. The city of Zurich secured its influence outside its walls by granting stake citizenship rights to residents of surrounding villages and small towns and by concluding castle rights with nobles and monasteries. Another means of expanding urban influence was the acquisition of rulership rights by urban noble families (court rulers). Under Mayor Rudolf Brun , Zurich then began to acquire subject areas directly. This was made possible by the fact that the Habsburgs pledged their property on the right bank of the Rhine in smaller parts to regional and city Zurich aristocratic families such as B. the Brun and Mülner. At the turn of the 14th to 15th centuries, many of these noble families found themselves in financial difficulties and passed on their Habsburg pledges to the city of Zurich for money. The town came into the possession of the lordships of Greifensee , Grüningen and Regensberg and Maschwanden-Eschenbach-Horgen. These areas were supplemented by the purchase of the imperial bailiffs in and around Zurich around 1400. In addition, there was the growing demand for castle rights with Zurich among monasteries, cities, communities and nobles, because of the shift of Habsburg politics away from eastern Switzerland and the crisis of Habsburg power made the sovereign protection of Zurich more effective and career opportunities more attractive. The castle rights often included not only mutual military assistance, but also obliged the beneficiary to keep his castles open for Zurich, to submit to the city's jurisdiction and sometimes also contained a right of first refusal for the city.

In connection with the imperial war against Duke Friedrich IV. Of Austria proclaimed by King Sigismund , the city of Zurich occupied parts of the Habsburg Aargau in 1415 ( Kelleramt , Freiamt Affoltern ) and began a single-minded territorial policy, also with royal support for the takeover of the Habsburg county of Kyburg and led the Landenberg rule Andelfingen . In 1433, Sigismund also granted Zurich the ban on blood over all former Habsburg areas. The city of Zurich also asserted its sovereignty over all areas with whose owners it had a castle right, e.g. B. the rule of Wädenswil of the Order of St. John or the communities of Rüschlikon , Meilen , Fluntern and Albisrieden of the canons of Grossmünster. When the city council bought an area for Zurich, it had to respect the traditional rights and the administrative regulations of the acquired area. Each acquisition became a separate administrative district, which resulted in a rather inconsistent and confusing administrative structure of the urban area. A distinction was made between upper and land bailiffs according to the type of administration . Every attempt by the city to unify its territory was seen by the residents of the affected areas as an interference with their "old freedoms" and violently opposed. The inconsistent picture was completed by the fact that numerous jurisdictions continued to exist within the ruled area of the city, in which private individuals or monasteries held the lower judicial powers.

The expansion of the city of Zurich led to the conflict with Schwyz on upper Lake Zurich over control of the County of Uznach , the County of Sargans and the rule of Gaster , which culminated in the Old Zurich War . Zurich's mayor Rudolf Stüssi declared war on Schwyz in 1439. The other confederates supported Schwyz, which is why Stüssi agreed to a provisional armistice in 1440. Stüssi then negotiated with Emperor Friedrich III. and obtained the promise to transfer the counties of Uznach and Toggenburg to Zurich in return for the return of the county of Kyburg to Habsburg, as well as military support from Habsburg. After the renewed outbreak of hostilities, Zurich suffered a defeat in the battle of St. Jakob an der Sihl on July 22, 1443, and Mayor Stüssi was killed. Ultimately, Zurich was only saved by the Armagnak invasion of the Swiss Confederation. After their withdrawal and the victory of the Confederates over a Habsburg army near Bad Ragaz , peace was concluded in 1450: Zurich lost the farms to Schwyz and had to give up its expansion plans into the Linth area. Violent internal pro-federal and pro-Habsburg disputes inside Zurich now came to an end.

The long war and the repeated plundering of the landscape by the Confederates seriously damaged Zurich's economy. This also initiated a move away from long-distance trade by the Zurich nobility. Instead, the families capable of being advised now sought to serve the city as bailiffs or civil servants and became an "administrative patron". Noble lifestyle, representation, the acquisition of imperial coats of arms as well as the accolade belonged to the usual external characteristics of this new urban upper class. The population fell from 7,000 to less than 5,000 during the Zurich War, the first heyday of Zurich was definitely over, Zurich threatened to fall back into the rank of a small town.

During the conquest of Thurgau (1460) and the Waldshut War (1468), Zurich fought again on the side of the Swiss Confederation and, due to its economic and military importance, rose to become a suburb of the old Swiss Confederation towards the end of the 15th century . Zurich convened the Diet and chaired it until the end of the Old Confederation in 1798. The territory was rounded off with the acquisition of Winterthur (1467), Stein am Rhein (1459/84) and Eglisau (1496). In the Burgundian Wars , Zurich played a leading role under Mayor Hans Waldmann . All of Waldmann's efforts to further expand Zurich's position in the Confederation, however, failed due to resistance from Bern and the rural cantons. After the Waldmann trade , an inner-city intrigue, there was an uprising of the peasants in the Zurich area in 1489 and Hans Waldmann was executed. Through the mediation of the Swiss Confederation, an understanding with the landscape came about in Waldmann's proverbs . The concessions to the peasants were insignificant, but the efforts to unify and centralize rule over the landscape came to an end. A government participation of the landscape did not come about, but a right of participation of the landscape was established in important decisions. This institution played an important role during the Milan Wars and the Reformation . In spite of this, the landscape dominated by Zurich actually had no political rights and, depending on their status, was governed by local resident bailiffs or by upper bailiffs living in the city who came from the Zurich nobility and were appointed by the city council. The feudal rights of the manor in the subject areas were mostly in the hands of the city or city families and the associated monetary payments and compulsory labor were demanded by force until the 19th century if necessary. An increasing number of municipal ordinances (→ mandates ), which on the one hand had moral (e.g. ban on dancing, playing, dress code), on the other hand had economic-political goals (e.g. trade regulations, restriction of traveling), had an effect on life in the countryside and emigration). These so-called "moral mandates" sometimes led to open resistance in the countryside, as in the forest man trade, when the ban on keeping large hunting dogs for farmers led to an uprising.

Even after Waldmann's fall, Zurich represented the interests of Habsburg in the Confederation, while Bern exerted influence on France . Emperor Maximilian's attempt to reunite the Confederation more closely with the Reich led to a change of front and Zurich took part in the Swabian War of 1499. During the Milan Wars (1500–1522), Zurich sided with the Pope and fought against the recruitment of federal mercenaries for France . The federal war campaigns to Milan again forced Zurich to call up the population of the countryside for military service, which was initially tolerated after a referendum. After the defeat at Marignano (1515), in which around 800 people from Zurich fell from town and country, there was another uprising in the countryside, as the mercenary leaders from the town were held responsible for the disaster. The so-called gingerbread war was settled in December 1515 with the exemplary execution of some mercenary leaders.

In the late Middle Ages, Zurich was a larger medium-sized town with an average of around 5,000 inhabitants, such as Bern, Schaffhausen, Lucerne and St. Gallen. As big cities, Basel and Geneva had around 10,000 inhabitants. After the great plague of 1348/49, the population declined to below 4000 by the middle of the 15th century, before growth began again. Within the city, the number of noble families declined and the bourgeois patrician families also fell sharply in favor of guild citizens. After 1378, membership in a guild was a prerequisite for granting citizenship and, conversely, almost all guild trades were tied to membership in a guild until the end of the 15th century. Around 1400, Zurich citizenship cost around seven guilders, with a fluctuating contribution to the city's construction costs. Zurich's financial strength was rather modest in the late Middle Ages. Based on the average wealth of 243.6 guilders in 1417, Zurich was behind Freiburg i. Ü. (320 guilders, 1445), Bern (373 guilders, 1448) and Basel (approx. 400 guilders, 1429). According to the tax register of the 15th century, around a third of the population belonged to the lower class (journeymen, servants, single women, poor craftsmen) with assets of up to 15 guilders, another third belonged to the upper lower class (craftsmen), around another third to the middle class with assets up to 1000 guilders. What remained was an upper class of around 5 percent of the population with assets of over 10,000 guilders. They held around two thirds of the total assets, while the lower class and the upper class with around two thirds of the population held around five to ten percent of the total assets.

Reformation 1519–1531

Due to the consolidation of rule in the hands of the city council at the end of the Middle Ages, the city-state also always received power and control over the church. During the Occidental Schism from 1378 to 1417, Zurich and the Confederation belonged to Pope Urban VI. and his successors. The schism encouraged the council to take over church powers, which continued into the 15th century. The Pope allowed the council to participate in the filling of the benefices of the spiritual foundations and in 1479 the city received an " Jubilee Draft " based on the model of the Jubilee Draft of Rome of 1475 to finance the new building of the water church. To propagate this indulgence, the first printing press in Zurich was set up in the Predigerkloster. Zurich's close relationship with the papacy was primarily based on the popes' need for federal mercenaries for their Italian policy. In 1512, on the occasion of the piano procession , Zurich, like other Swiss Confederation towns, was awarded a Julius banner . As Zurich was the suburb of the Confederation, the papal legate Matthäus Schiner temporarily settled in Zurich, making the city temporarily the center of papal politics north of the Alps. As recently as 1514, the papal envoy, who lived in the city, guaranteed those who visited all seven churches in Zurich the same indulgence as those who visited the seven main churches in Rome. The Zurich mayor and military leader Marx Röist was one of the largest pension recipients of the curia and his son Kaspar Röist became commander of the Swiss Guard and fell in the Sacco di Roma in 1527 . The relationship with the Bishop of Constance, to whom the city was subject to canon law, was more conflictual. The council increasingly claimed its jurisdiction over the clergy and, in general, the sovereignty of spiritual courts over lay people, and interfered in tax issues and in the appointment of benefices in episcopal areas. In 1506, the council finally officially subjected the clergy to the lower municipal jurisdiction. At the end of the 15th century, the monasteries and monasteries in the urban area had also completely fallen under the tutelage of the city, even in the election of the new abbess of the Fraumünster and in filling the spiritual benefices of the Grossmünsterstift the council now had a say.

At the transition from the 15th to the 16th century, rice walking was the greatest political and economic problem for Zurich and the entire Swiss Confederation. On the one hand, the nobility and the state benefited financially from trading in mercenaries, on the other hand, the corruption, population loss and moral decline associated with this branch of industry led to unmistakable grievances. As early as 1508, Zurich therefore campaigned in vain at the Swiss Confederation's meeting of the Swiss Confederation to forbid individual recruitment for military service and the conclusion of private contracts for mercenary armies. After heavy losses of the Zurich troops in the Battle of Novara in 1513 and the defeat of the Confederates at Marignano, the number of critics of the mercenary system increased again. That is why Ulrich Zwingli , a well-known critic of mercenaries, was appointed parish priest at the Grossmünster in 1518 . With the support of the council, Zwingli began to introduce the Reformation in Zurich in 1520. In doing so, Zwingli had important steps in disputations before the council by church people who represented different opinions, discussed controversially, after which the council decided independently on the measures and their implementation. In the course of the second Zurich disputation in autumn 1523 , this cautious and step-by-step approach led to the uprising of more radical Reformation groups and to the establishment of the first Anabaptist congregation around Felix Manz and Konrad Grebel . The dispute with the Anabaptists ended in 1527 with the execution of Felix Manz by drowning in the Limmat and the ostracism and expulsion of their followers from the dominion of the city. In 1525 Zwingli wrote his views in a first creed, but an agreement with the German Reformation under Luther failed in 1529 in the Marburg Religious Discussion . (→ Reformation and Counter-Reformation in Switzerland )

The dissolution of the monasteries in the ruled area of Zurich, which was enforced by the city council in the course of the Reformation, and the transfer of church goods and rights to the city's property, triggered unrest in the countryside. The peasants demanded the abolition of serfdom and the burdens connected with it, the redemption of the basic interest, the abolition of the small tithe , the abolition of all innovations introduced by the council in the administration of the countryside and the restoration of special rights and old customs. With the bloody suppression of the peasant uprisings in southern Germany in mind, the peasants agreed to a compromise with the city: Serfdom and the minor tithe were abolished, but only if the latter did not belong to a gentleman from outside the city's sphere of influence. As a result of the secularization of the monasteries and religious foundations, the city gained extensive property ownership and high income, so that taxes in Zurich only had to be levied in exceptional cases until the 19th century. Through the Reformation, the supervision of the church, the school and the poor system was transferred from the Catholic Church to the city of Zurich. The associated expenses were met from the income of the former monasteries and monasteries. The examiners' convent , consisting of the city clergy and presided over by the Antistes , and the synod of clergy of the entire city of Zurich acted as state authority over the church . The Examinatorenkonvent was also given the task of "advising" the city council on all important decisions so that it could not make any decisions contrary to the Bible. In fact, after the Reformation, the political organs of the city of Zurich were controlled by the Reformed clergy. Zwingli himself never held a political office in Zurich; he exercised his influence from the pulpit.

The five inner towns of the Swiss Confederation opposed the Reformation with fierce resistance and tried to terminate the "heretical" Zurich. On the other hand, the reformed federal cities of St. Gallen , Schaffhausen , Basel and Bern, as well as the cities of Mulhouse and Biel that were facing them , came closer together . Connections were even made to Constance and Strasbourg . Finally, in 1528 the Reformed towns and Constance signed the Christian castle law to defend the Reformation. For their part, the Catholic towns formed the "Christian Association" with Habsburg in 1529 . When the Catholic places prevented the spread of the Reformation in the common lordship and in the prince abbey of St. Gallen , Zurich declared war at Zwingli's insistence.

The First Kappel War (1529) ended without a military confrontation in a mediation ( First Kappeler Landfriede ). Zwingli and the city council continued unsuccessful alliance negotiations with European powers and actively supported the Reformation in the common rulers. When Zurich openly supported Toggenburg in its rebellion against the Abbot of St. Gallen, the Second Kappel War against the Catholic towns broke out in 1531 . Zurich suffered a defeat near Kappel am Albis , in which Zwingli was also killed. The Second Kappeler Landfriede of 1531 ended the further spread of the Reformation in the Confederation.

The new faith was strengthened by Zwingli's successor Heinrich Bullinger , who worked out the first Helvetic Confession of the Reformed Church in 1536 and the Consensus Tigurinus with Calvin in 1549 . Heinrich Bullinger was an Antistes from 1531–1575 and Rudolf Gwalther from 1575–1586 , as the head of the Reformed Church in Zurich was called. They maintained numerous contacts across Europe, especially with representatives of the British state church. During her time, many Protestant refugees from Ticino, Italy, France and England were accepted. Subsequently, these contributed significantly to Zurich's economic prosperity through handicrafts, the production of as yet unknown textiles and trade.

After the defeat at Kappel, however, the leadership of the Reformation movement passed to Geneva and Bern. In Zurich a political sobriety spread which, according to Gordon A. Craig, became the epitome of the Zurich style: “A modesty in the goals that were set, a willingness to orientate oneself towards what is feasible and tangible and to renounce lofty goals and grandiose ambitions ». This attitude and the negative attitude towards mercenaries caused Zurich to become less important. Compared to Bern, Geneva or Basel, Zurich was of a provincial format until the 19th century, which was particularly evident in the public buildings and the way of life of the majority of the citizens, as well as in cultural life.

Early modern times: Zurich in the Ancien Régime

The period after the Reformation ended the stormy phase of the military expansion of the Old Confederation and thus also of the territory of the city of Zurich. Further acquisitions were only made by purchase, the more important of which were the Vogtei Laufen (1544), the Johanniterherrschaft Wädenswil (1549) and the Landvogtei Sax-Forstegg in the Rhine Valley (1615).

The confessional split in the Confederation continued after the Kappel Wars. Zurich remained connected to the other Reformed cities in southern Germany. In 1584, Zurich and Bern entered into an alliance with Geneva and also renewed the connection with Mulhouse and Strasbourg . Zurich troops repeatedly went out in support of these cities. Ever Zurich in the 16th century by the action was Heinrich Bullinger into a center of Calvinist - Reformed world. Religious refugees from France ( Huguenots ) and Ticino settled on the Limmat; they brought about an economic and intellectual boom in the city, as they brought new branches of industry (textile industry) and knowledge from their homeland.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the city's citizenship became more and more isolated from the outside world by issuing ever stricter regulations for the acceptance of new citizens. The aristocratic and absolutist behavior of the city council also corresponded to this closure . The previously practiced participation of the guilds and the countryside in government came to an abrupt end. In 1624, for example, under the impact of the Thirty Years' War , the city council decided to invest large sums in the construction of a modern, third city fortification . The financing should be done through a tax that was advertised without prior survey of the landscape. The unrest that broke out was ruthlessly broken through the deployment of the military, especially in the regional bailiffs of Wädenswil and Freiamt. Afterwards, the population of the countryside was so intimidated for a long time that during the Peasant War of 1653 the situation in the ruled area of Zurich remained so calm that even troops could be sent against the Bernese and Lucerne peasantry. Since Switzerland's independence from the German Empire was confirmed as part of the Peace of Westphalia (1648), Zurich no longer referred to itself as the "Imperial City of Zurich", but confidently as the "Republic of Zurich". Zurich moved up to the same level as the sovereign city republics of Venice and Genoa . As an outward sign of the new position, a new, splendid town hall was built, which was inaugurated in 1698 for the fiftieth anniversary of the Peace of Westphalia. Domestically, the town hall signaled the completion of the oligarchization of the city regiment.

Since Zurich was the protective power of the Reformed believers in Switzerland, conflicts with the Catholic places arose again and again. When Schwyz expelled all Reformed families from Arth in 1655 , Zurich intervened again militarily in the First Villmerger War against the Catholic towns in central Switzerland, but only received support from Bern from the Reformed side. This and the unfortunate warfare led to another defeat of Zurich. The predominance of the Catholic places seemed confirmed. A little more than fifty years later, Zurich intervened again in 1712 together with Bern in favor of Reformed subjects under Catholic rule, this time in Toggenburg . The Second Villmerger War ended in favor of the Reformed cities and brought the end of Catholic supremacy in the Old Confederation.

The 18th century was a heyday of intellectual life and culture in Zurich. The German poet Wilhelm Heinse was astonished to discover that there were over 800 citizens in Zurich who would have had something printed. Numerous societies of all kinds acted as the engine of Zurich's intellectual life, in which discussions and writing took place undisturbed by the censors. At that time there were already several weekly newspapers in Zurich. The “Zürcher Zeitung”, founded in 1780, has existed as the “ Neue Zürcher Zeitung ” (since 1821) to this day. The “Modestia cum Libertate” freemason lodge in Zurich, founded in 1771, also still exists today and is domiciled at Lindenhof. Goethe is said to have received the impetus to join the Freemasons during his visit to Zurich in 1779 .

In contrast to western Switzerland and Berne, the new ideas of the Enlightenment in Zurich were not exclusively obtained from France, but mainly from Germany, the Netherlands and England. The German philosophers Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and Christian Wolff were decisive. The preference of Zurich scholars for English thinking set a conscious counterpoint against the French-influenced Bern and was also the subject of the well-known literary dispute between Zurich's Johann Jakob Bodmer and Johann Jakob Breitinger and the German "literary pope" Johann Christoph Gottsched .

The concentration of important personalities of intellectual life in Zurich brought the city a certain fame. The work of the literary critic and history professor Johann Jakob Bodmer was particularly responsible for this. As the "father of the youngsters" he was the teacher of two generations of important philosophers, cultural workers and artists; among others the poet and painter Salomon Gessner , the theologian and physiognomist Johann Caspar Lavater , the painter Johann Heinrich Füssli and the pedagogue Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi . The connection between Bodmer and Jean-Jacques Rousseau contributed particularly to the spread of his philosophy in the city on the Limmat. Almost all of Zurich's great intellectuals "made a pilgrimage" to the famous French philosopher who lived in exile in Môtier in Neuchâtel. Leonhard Usteri in particular was in close contact with Rousseau, but he did not succeed in persuading him to move to the Limmat. Via the connection to Usteri, only the herbarium Rousseau reached Zurich, which is now in the possession of the central library . In the field of natural sciences, the doctor and natural scientist Johann Jakob Scheuchzer should be emphasized.

The new ideas had only limited influence on the administration and the state. The bailiff of Greifensee and Eglisau, Salomon Landolt sets an example for a rational administration of his bailiwick, but there can be no talk of enlightened absolutism in Zurich. On the contrary, the outdated medieval forms became rigid and power was concentrated in the hands of a few "regimental" families. Farmer Jakob Gujer , known as Kleinjogg, from the Zurich countryside, who tried to initiate a fundamental reform of agriculture based on physiocratic theories , received European attention . His views were presented to a pan-European audience by Hans Caspar Hirzel , who was in contact with all the luminaries of German literature at the time. During a visit by Klopstock to Hirzel, the boat trip on Lake Zurich, sung about in a well-known ode by Klopstock, took place. Hirzel was a co-founder and first head of the Helvetic Society in 1762 .

The long period of peace between 1712 and the collapse of the city republic in 1798 increased material prosperity considerably. In particular, the families who were involved in the wholesale trade in silk and cotton benefited from the extensive trade relations, the stable political order and the low taxation. The greatest political scandal of the time also shows the limits of cultural openness. When the theologian Jakob Heinrich Meister published his work on the psychology of religion, "De l'origine des principes religieux", in which he massively attacked the belief in revelation and thus took up and developed Voltaire's thoughts, he was banned from the rulership of Zurich and his name was deleted from the list of citizens and burned his book by the executioner. Meister received Voltaire's praise for this, but had to spend a long time in exile in Paris.

The political situation in the city republic of Zurich in the 18th century was shaped by reform requests from various sides. Thanks to their wealth of funds, the up-and-coming class of cotton and silk manufacturers was able to gain more and more influence in the councils against the will of the city's artisans. Under pressure from the guilds and the rural population, there was therefore a constitutional revision as early as 1713, which, however , brought only minor changes with the Sixth Jury's Letter : The influence of the money aristocracy was somewhat curbed, but the basic interest and tithe were not abolished. The council then ruled more and more arrogantly and absolutist over the citizens of the city. In 1777 he made an alliance with France without even consulting the civil parish.

In the countryside, the city's regiment became effective through numerous mandates that regulated the religious and moral life of the subjects in every detail. Furthermore, the city authorities kept a strict watch over the city's monopoly in the economic field: the exercise of all trades that served not the everyday needs of the rural population but the manufacture of luxury or export goods were strictly forbidden. Any activity in foreign trade was also reserved for the city's citizens. Only the publishing system brought work , in which wealthy townspeople, the so-called publishers, had thousands of craftsmen in the countryside process raw products at home . The refinement of the manufactured goods, especially silk and cotton , and the sale were reserved for the urban lords. Nevertheless, the publishing system brought a certain prosperity to the communities on Lake Zurich, in the Oberland and in the Free Office in particular, and created an educated upper class in the countryside that strived for equality with the townspeople.

After the French Revolution (1789), the rural upper class came to the city council with petitions. She called for a constitution for the countryside, the abolition of the city's economic monopoly, the abolition of feudal burdens and better educational and career opportunities. However, these petitions did not fall on fertile ground: when, for example, the so-called Stäfner Memorial was drawn up in 1794 , the council had the leaders of the movement arrested and sentenced before the petition could even be submitted to the government. The dispute over these events, the Stäfner trade , mobilized the entire landscape and also the city, where a small part of enlightened citizens demanded reforms based on the French model. The excitement in the population no longer decreased and when the French marched into the Old Confederation from the west in 1798, the old order was overthrown. The radical leader of the landscape, the Stäfner Johann Kaspar Pfenninger , who had returned from exile , forced the council to resign. A provincial commission, composed mostly of representatives from the landscape, was convened to draw up a constitution for Zurich. Before she could finish her work, Zurich and its landscape had to submit to the Swiss constitution dictated by France on March 29, 1798. With that the Republic of Zurich ceased to exist. As the canton of Zurich, their area became an administrative district of the Helvetic Republic .

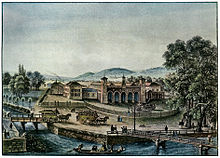

Grendeltor around 1820 Right the Ravelin "Kratz". Engraving by Hans Jakob Kull

The bastion at the Rennwegtor around 1800

The Wellenberg tower and the old cathedral bridge around 1800

View from the Rathausbrücke towards the lake around 1835, Conrad Caspar Rordorf

Zurich in the Helvetic Republic (1798–1803) and mediation (1803–1815)

The Helvetic Revolution ended the administrative unity of the city and canton of Zurich. With the adoption of the Helvetic Constitution on March 29, 1798, Zurich submitted to the new legal system and on April 26, elected the municipality (city authority) of Zurich, one day later the city was occupied by French troops without a fight.

During the coalition wars in 1799, French and Austro-Russian armies fought twice in the vicinity of Zurich. In the First Battle of Zurich on June 4, 1799, the city was occupied by Austrian troops. The second battle near Zurich on 25./26. September 1799 brought the French victory. The wealthy families of Zurich had to contribute considerable sums to the “liberation” by France and lost lucrative sources of income by lifting the feudal burdens. The common population was affected by the billeting and requisitions of the armies passing through. Since trade and the economy also suffered considerably from the turmoil, the Helvetic authorities in Zurich were almost exclusively occupied with averting the financial ruin of the new canton and raising new money. If the anti-French coalition were to win, the old aristocratic government threatened to return. A first census in the Helvetic Republic for Zurich in 1800 shows a population of around 10,000.

The turmoil in the government of the Helvetic Republic also had an impact on the cantons: Between 1800 and 1802 there were a series of coups d'état within the Helvetic Directory, in each of which a radical, revolutionary and unitarian -minded government replaced a conservative , federal one and vice versa . After the French troops withdrew in July 1802, the conservative party won in Zurich. During the Stecklik War , the Helvetian government tried in vain to force the city back into obedience through a siege and bombardment of Zurich in September 1802 - the turmoil only ended when the French marched into the city again.

The canton of Zurich was restored as a political unit through the mediation constitution . The representative, democratic cantonal constitution granted the city political privileges (Grand Council: 11,000 city dwellers appointed 75 councilors, 182,000 rural residents 120 councilors; Small council: 15 representatives from Zurich, 2 representatives from Winterthur , 8 representatives from the countryside). With the new constitution, the city of Zurich was also founded. On June 25, 1803, the 15-member city council was constituted for the first time. When the assets of the city and canton were separated, the city received the goods of the Fraumünsteramt, the Sihlwald, the Adlisberg and the Hard as well as assets from the canton with the tax certificate of September 1, 1803. In the rural population, the partial reintroduction of the old order, especially the basic interest and tithes, aroused resentment, which aired itself in the buck war . This uprising could only be put down thanks to a federal military intervention. The conservative turnaround was also sealed by the reintroduction of compulsory guilds. At the same time, the industrialization of Zurich begins with the establishment of the first mechanical cotton spinning mill with an attached machine factory in Neumühle in front of Niederdorfporte by Hans Kaspar Escher .

Within Switzerland, Zurich had become a suburb of Switzerland due to the mediation constitution , whereby the Zurich mayor during the mediation period, Hans von Reinhart , twice used the title "Landammann der Schweiz" and the Confederation and Zurich at important events of the time, such as Napoleon's coronation or represented at the Congress of Vienna .

In 1807, for the first time since the Reformation, the small council allowed a Catholic parish in Zurich. -see also

Restoration and regeneration 1815–1839: The end of urban domination in the canton

After the fall of Napoleon, Zurich, whose government was still that of the canton, adopted a new constitution. The political equality of the landscape with the city was theoretically preserved, but in practice two thirds of the Grand Council were occupied by city citizens. A new layer of wealthy, aristocratic urban bourgeoisie found themselves in leading positions, who held an undisputed position of primacy in government, justice and administration and also controlled the church hierarchy via the right to vote. The landscape finally achieved economic equality with the city, but the guild constitution remained in place and was simply extended to the craftsmen in the country towns and villages. The landscape was divided into districts, which were administered by senior officials who, like the governors in former times, combined judicial and executive powers in one hand and also had their official residence in the governors' castles.

The peasants of the countryside were the least satisfied with the new constitution, as the taxes on their estates remained and now became a main source of income for the state. The urban-ruled government meant further disadvantages for the landscape. The government, for example, delayed the urgent expansion of the infrastructure in the heavily industrialized landscape, because it was able to weaken the competitive pressure on urban companies. In general, the conservative government was the lack of innovation and initiative was the greatest weakness of the conservative government, which, according to Karl Dändliker , was engaged in a "stagnant dodger". The peasant opposition was thus strengthened with the rural manufacturers who wanted a more contemporary economic order. Together with liberal politicians from the city of Zurich such as Paul Usteri and Ludwig Meyer von Knonau , the peasant opposition called for a modern government with a separation of powers , economic freedom , popular sovereignty and the abolition of tithes and basic interest. The center of the liberal opposition was the Political Institute in Zurich, which had been founded by Meyer and Usteri in 1807 as the city's first law school, its mouthpieces were the Neue Zürcher Zeitung and the Schweizerische Beobachter . Both papers celebrated the Greeks' struggle for independence, reported on the advance of liberal ideas abroad and commented critically on conservative politics in Germany. In 1829, the opposition forced freedom of the press at a favorable moment, when the conservative State Councilor Hans Konrad Finsler had to resign after the scandal surrounding the collapse of Bank Finsler . The legislative initiative has now passed from the State Council to the Grand Council.

The reporting of the censored newspapers about the July Revolution in Paris in 1830 boosted the revolutionary mood in Zurich's landscape again. The initiative for the reform came from the lakeside communities, which induced the liberal lawyer Ludwig Snell , who had fled from Germany , to present a liberal draft constitution in the "Küsnachter Memorandum". After the people's assembly in Uster on September 22, 1830 ( Ustertag ), the government decided to forestall a revolution and have a new constitution drawn up. The constituent assembly leaned closely on Snell's draft and in 1831 put forward a constitution that implemented core liberal demands. Zurich became a “free state with a representative constitution” and, as a model liberal state, served as a model for liberals throughout Western Europe. The principle of popular sovereignty was established, if only indirectly, with the Grand Council exercising government as the representative of the people. Furthermore, the separation of powers and the abolition of tithe, indirect taxes and the political equality of all canton citizens were established and the compulsory guild was abolished. The city's political supremacy was broken, with two thirds of the seats in the Grand Council of the Countryside.