Muri monastery

The Muri Monastery is a former Benedictine abbey in Switzerland . It is located in Muri in the canton of Aargau , in the center of the Freiamt region . The listed house monastery of the Habsburgs is one of the most important landmarks in Aargau. Due to its great historical, architectural and cultural importance, it is classified as a cultural asset of national importance .

The monastery was founded in 1027 by Ita von Lorraine and her husband, the Habsburg count Radbot . Five years later, the first monks sent from Einsiedeln began building the abbey. Muri was a double monastery for a little over a hundred years until the Hermetschwil Benedictine monastery split off at the beginning of the 13th century . The abbey acquired goods and rights in today's cantons of Aargau, Lucerne , Thurgau and Zurich . After the conquest of Aargau in 1415, the Confederates replaced the Habsburgs as patrons. After internal reforms, Muri rose to become the richest abbey in Switzerland in the 17th century, was given the rank of prince abbey in 1701 and then acquired a rulership on the Neckar . The decline began in 1798 with the French invasion and the political upheavals that followed. In 1841, the canton of Aargau abolished the monastery and thus triggered the Aargau monastery dispute, which resulted in violent domestic and foreign political tensions. The Benedictines moved to Sarnen on the one hand to teach at the college there, and on the other to Gries near Bozen , where they founded the Muri-Gries Abbey in 1845 .

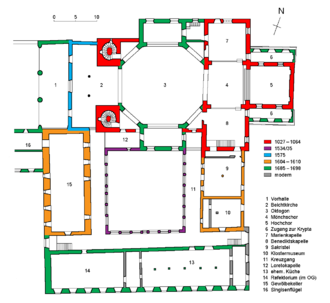

The core of the extensive monastery complex is the monastery church of St. Martin , which dates back to the middle of the 11th century. It combines elements of the Romanesque , Gothic and mainly Baroque . The three towers and the octagon , the largest central dome building in Switzerland, are characteristic. The adjoining cloister contains an art-historically significant glass painting cycle , the monastery museum and an exhibition with pictures by the painter Caspar Wolf . Of particular importance is the Loreto Chapel , whose crypt has served as the burial place of the Habsburgs since 1971. The largest building of the monastery is the Lehmannbau, which was built at the end of the 18th century, and its east wing has the longest classicist facade in the country.

Today the Muri monastery is a cultural center of national importance. The five organs of the monastery church , which are regularly used for concerts, contribute to this. The other buildings are used for a variety of purposes (school, district and community authorities, public library, specialist library and nursing home).

Location and overview

The monastery is located in the district of Wey, near the northern edge of the buildings on a terrace that slopes slightly to the east and north. The approximately 250 x 200 meters large area is to the east of the pass leading to the train station Aarauerstrasse ( main road 25 limited), south of the over the Lindenberg leading Seetalstrasse . In the west it borders on the center of Wey with the Leontiusbrunnen .

The extensive monastery complex consists of several parts. The St. Martin monastery church is slightly offset from the center of the area . To the south is the convent wing, which surrounds the cloister on three sides . The narrow Singisen wing extends to the west. The so-called Lehmannbau, which is made up of the east wing and the south wing, is not connected to these buildings. At the northern end of the east wing there is a modern functional building.

history

Founding and striving for independence

The only source about the first decades of the monastery is the Acta Murensia , a chartular chronicle written around 1160 by an anonymous author . According to this, before the monastery was founded, Muri had its own church owned by local farmers . Before the turn of the millennium, they placed themselves under the protection of the Habsburg Lanzelin , who, however, abused his position of power by driving out the free farmers and replacing them with serfs . Lanzelin's son Radbot , who is considered to be the founder of the Habsburg family castle , violently put down an uprising by the heirs of the expellees. He finally appropriated the property in Muri and had a house built there for himself. Around 1025 a feud with his younger brother Rudolf led to the looting of the place.

Radbot married Ita of Lorraine and gave her the goods in Muri as a morning gift. Ita learned of the illegitimate origin and wanted to atone for the guilt that had been imposed on him. On the advice and with the help of her brother-in-law Werner , the Bishop of Strasbourg , she was able to persuade her husband in 1027 to donate the goods to a new monastery to be founded. Radbot asked Embrich, the abbot of Einsiedeln , to send monks. The construction of the monastery began in 1032 under the direction of Provost Reginbold. He immediately had the existing parish church of St. Goar demolished and rebuilt a little further south. This measure served to secure the abbey legal succession to the parish of Muri, which was bound to the property. Rumold von Konstanz , the Bishop of Konstanz , consecrated the monastery church , which was built in place of the parish church , on October 16, 1064 . In 1065 Provost Burkard was elected first abbot.

Count Werner I was a supporter of the Hirsau reform and was able to enforce it in 1082 after he had asked Abbot Giselbert of St. Blasien to send monks to Muri. The reform also included the formation of a monastery domain. The Muri monastery was now a priory of St. Blasiens and elected the bailiff himself. However, this approach did not work because the two non-Habsburg bailiffs, elected one after the other, were unable to protect the monastery adequately. In 1085 Werner I therefore took over the patronage again. In order to legitimize the legal status of the abbey (free choice of abbot, binding of the bailiwick to the Habsburgs), the count and convent drew up a "testament" dated back to 1027, which Bishop Werner von Strassburg called the founder of the monastery and founder of the Habsburgs. In 1086 the count obtained a document based on this, which he had the College of Cardinals confirm. His son Albrecht was able to obtain a letter of exemption from Emperor Heinrich V in 1114 . In this way arose office Muri , where the Habsburgs now instead of the increasingly meaningless becoming Lenzburger the blood jurisdiction exercised.

In the 1130s the convent split into two groups, which Bishop Werner and Ita regarded as the monastery donors. The reason for the dispute was the attempt by the Habsburg bailiffs to bring the parish of Muri back into their possession based on the forged will. Two papal umbrella letters issued in 1139 and 1159 confirmed the legal status of the abbey, but there was still no listing of the property (with the exception of the churches located outside Muri). These circumstances induced a supporter of the "Ita Party" to write the Acta Murensia. In it he tried to prove that the church and parish had belonged to the abbey since the foundation. Gradually this view took hold, but it was not until 1242 that the Habsburgs finally renounced all ownership claims.

From the Habsburgs to the Confederates

From 1083 Muri was a double monastery when the men's and women's convents were attached. A building adjacent to the monastery church that was demolished in 1694 is assumed to be the location. The two convents were spatially separated around 1200 with the founding of the Hermetschwil monastery six kilometers to the north . At the beginning of the 14th century it gained economic independence with its own estates, but remained under the spiritual direction of the abbot of Muri. Monks from Muri, on the other hand, settled the Engelberg monastery, founded by Konrad von Sellenbüren , in today's canton of Obwalden in 1120 .

Relations with the Habsburgs gradually waned and the monastery church was last used as a burial place in 1260. The reasons for this were varied: The main line connected to the monastery increasingly had disputes with the Laufenburg line, which split off in 1232, and in 1282 shifted its center of power to Vienna . In addition, Agnes of Hungary founded the Königsfelden monastery in nearby Windisch in 1308 to commemorate her father Albrecht I, who was murdered there. In the decades that followed, Muri quickly lost its importance. According to the monastery chronicle, fires in 1300 and 1363 caused great damage. In 1386 the Confederates set fire to the monastery during the Sempach War . Duke Leopold IV made several donations to the monastery in 1399 and 1403, with the explicit reference to the damage suffered.

In the middle of the 14th century, the Habsburgs had pledged the offices of Muri and Hermetschwil . Duke Leopold III. allowed the pledge to be redeemed in 1379 , after which the offices came into the possession of the Gessler family . This ministerial family , which gained notoriety through the tell saga , was represented by subordinates. After the death of Heinrich III. Gessler wanted the abbey to eliminate the legal violence caused by the pledge and to take over the pledge itself. In 1408, Duke Friedrich IV granted the appropriate permit. However, due to the following events, the intended change of ownership did not take place. When Frederick at the Council of Constance one of the three then reigning Popes, John XXIII. , helped to escape, King Sigismund asked the neighbors of the Habsburgs to take their lands in the name of the empire. In April and May 1415 the Swiss conquered Aargau. Muri was now part of the Free Offices , a common rule of the new sovereigns . On October 16, 1431, the six towns of Zurich , Lucerne , Schwyz , Unterwalden , Zug and Glarus issued a new umbrella letter confirming the rights of the abbey. Uri , which was accepted into co-rulership in 1532, did the same in 1549.

Possessions of the monastery

The monastic domain in Muri grew to an area of 1031.12 Jucharten (418.82 hectares ) by 1779 . It was mainly an arable farm, but the abbey also had forests and herds of pigs, horses and sheep. Almost a quarter of the area was accounted for by the Sentenhof , which was built around 1500 , mainly in the area of the neighboring municipality of Boswil . The only dairy farm in the region served the self-sufficiency with meat and dairy products. With an area of 112 hectares, the Sentenhof, which was sold in 1846, is today the largest private farm in Aargau. The monastery obtained fish from the bailiwick of Gangolfswil on Lake Zug , after which it was sold to Zug in 1486 from specially created ponds in Muri. The head of the domain was originally a provost , later a civil servant conductor, to whom several dozen employees were subordinate. Other important offices were the large waiter (wine cellar and kitchen), waiter (fish ponds and water supply), market staller (horses and wagons) and master tiller. Craftsmen worked on a daily wage as needed. In addition, there were numerous agricultural workers seasonally.

In the sovereign office of Muri , the abbey was the sole lord of the church, tithe and lower judge as well as the owner of all goods and farms. Most of the office consisted of the parish of Muri, which included the present-day parishes of Aristau (with Althäuser and Birri), Buttwil , Geltwil (with Isenbergschwil) and Muri. Then there were the hamlets of Grod, Grüt and Winterschwil in the northern part of the parish of Beinwil . The compulsory and lower court district exceeded these boundaries: It also included the hamlets of Brunnwil and Horben in the parish of Beinwil and part of Besenbüren in the Boswil district. Part of the parish of Muri, but not of the Muri office, was the Wallenschwil exclave in the Meienberg office . Another special case was the hamlet of Werd in today's municipality of Rottenschwil : There the abbey owned a third of the entire lower and blood jurisdiction (the other two thirds belonged to the cellar office of the city of Bremgarten ). The criminal court cases in the Official Muri completed the non-resident bailiff , the Lower Court was set up by a monastery and entlöhnter Ammann ago. A monastery chancellery has been guaranteed since the middle of the 16th century , which carried out all notarial tasks in the Muri office and also provided the clerk of the court.

Of particular importance were the church patronage , which the abbey received or acquired as a gift over the years. She strove to incorporate the patronage as quickly as possible in order to dispose of the proceeds of the church property (especially the tithes ). The churches in Eggenwil and Hermetschwil , which later became part of the Hermetschwil monastery, were part of the early equipment of the monastery . Bünzen was added in 1321, Villmergen and Sursee in 1399 , Lunkhofen in 1403 , Boswil in 1483 and Wohlen in 1484 . The goods north of Muri were mainly administered from the Muri-Amthof in Bremgarten, where the abbey had enjoyed tax exemption since 1397. The administration of the goods in the extensive parish of Sursee took place from the Murihof. From the time the monastery was founded, the abbey had owned twelve farms in Thalwil , and until 1244 it also owned the church there. The official building of the monastery (demolished in 1900) was on the shores of Lake Zurich . The free float in Gersau , Nidwalden , Alsace and Markgräflerland from the founding time has not been passed down since the 14th century. There were extensive extensions of ownership in the 17th and 18th centuries in Thurgau and on the Neckar (more on this in the next but one section ).

Crisis and reforms

The Muri monastery was never purely an aristocratic monastery and also accepted novices from lower social classes. In 1380 the convent elected Konrad Brunner to be the first abbot of large-scale farming. As in other monasteries, the rules of the order were no longer strictly adhered to and a benefice economy developed , with which the monks each financed their own household and servants. In 1402 Brunner had to appeal to a court so that the income from the parish Sursee could be used at least temporarily for the reconstruction of the monastery buildings. He also limited the number of benefices to a dozen so as not to overload the monastery economy. Visiting the baths in Baden or social events in Zurich was part of the monks' lifestyle . The celibacy was rarely enforced; for example, Abbot Johannes Hagnauer left four children.

In 1523 the Reformation began to spread from Zurich in the free offices. Although Abbot Laurentius von Heidegg had a son and was friends with Dean Heinrich Bullinger, the father of the reformer of the same name , he turned against the innovations. In 1529 several parishes in the catchment area of the monastery joined the Reformation, in Muri itself the new believers made up a slim majority. Troops from Reformed Bern , who had arrived too late for the battle of Kappel , occupied the monastery in mid-October 1531 and caused great damage in an iconoclasm . The Second Land Peace of Kappel , which was concluded a month later, resulted in the re-Catholicization of the Free Offices by the victorious central Swiss towns. Heidegg financed the repair and expansion of the monastery in part from his private assets.

The following abbots tried to push through the reforms decided at the Council of Trent , but met with fierce opposition from the Convention. The efforts under Abbot Jakob Meier , who had two concubines and who brought the monastery to the brink of ruin through mismanagement, suffered a setback . In 1596 he was arrested and deposed with the permission of the nuncio . Only Meier's successor, Johann Jodok Singisen , succeeded in consistently implementing the reforms. This included the introduction of the strict enclosure , the abolition of benefices, the replacement of servants by lay brothers and the systematic training of monks. With the support of the nuncio, Singisen was able to quickly break the resistance of the convent. He had the monastery expanded structurally; Until 1610 a building was built attached to the cloister , which is known today as the Singisen Wing. In 1622 he achieved the exemption of the abbey from episcopal jurisdiction. Pope Gregory XV confirmed this, but it was not until 1645 that the diocese of Constance finally consented after a compromise had been negotiated (confirmation of the election of a new abbot by the diocese). Due to his numerous services, Singisen is considered the second founder of the Muri Monastery. During his 48-year tenure, the convent grew roughly three-fold to 30 monks.

Rise to the prince abbey and territorial rule

In 1647 Abbot Dominikus Tschudi arranged for the relics of the catacomb saint Leontius to be transferred from Rome to Muri. As a result, the monastery was a much visited place of pilgrimage. During the Thirty Years War , monks from friendly monasteries in southern Germany repeatedly found refuge in Muri. In 1656 the church treasure was temporarily brought to Lucerne during the First Villmerger War for fear of looting. In 1651 Tschudi acquired the rule of Klingenberg near Homburg in Thurgau for the abbey . The central Swiss umbrella towns had asked him to do so, so that the rulership for sale remained in Catholic hands. The abbey, which now belonged to the court lordship in Thurgau , had to take out a loan to finance the transaction, the repayment of which stretched over several decades.

The most important abbot next to Singisen is Plazidus Zurlauben , who was very concerned about representation. A few months after taking office, in 1684 he decided to rebuild the monastery complex. On May 1, 1684, the catacomb saint Benedictus was brought to the monastery church in a translation ceremony. The beginning was made in 1685/86 the abbot's chapel and abbot's apartment. In 1694 a new west wing followed, in 1696 a new south wing. In addition, various economic buildings were built around the turn of the century. The most important building project concerned the monastery church, which no longer met the needs of the time. Between 1694 and 1697, Zurlauben had the nave replaced by an octagon based on the northern Italian model, and in 1698 the Loreto Chapel was built in the cloister . The renewed and expanded monastery complex was now predominantly characterized by baroque architecture; the construction costs amounted to more than 150,000 guilders . In 1700/01, Zurlauben also had Horben Castle built on the Lindenberg above Muri as a summer residence and rest home for the monks.

Zurlauben expanded the existing court and land rule of the Abbey in Thurgau: in 1693 he acquired the rule of Sandegg in Salenstein , five years later the rule of Eppishausen in Erlen . He achieved the greatest gain in prestige in 1701 when he acquired the title of prince abbot for himself and his successors at the imperial court in Vienna . As members of the imperial prince Council , the abbots of Muri had the right to diets take what they never took advantage. The abbey built a cohesive rulership territory on the upper Neckar, consisting of the goods and rights of impoverished imperial knights of the knight canton Neckar-Black Forest . The territory included several villages around Horb am Neckar and Sulz am Neckar . It all began in 1706 with the acquisition of the Glatt estate with Glatt Castle . The villages of Diessen, Dettlingen and Haidenhof followed in 1708, Dettensee in 1715 , Dettingen in 1725 and the Neckarhausen manor in 1743. The abbey spent 310,000 guilders on the territorial expansion.

During the Second Villmerger War in 1712, the monks again sought refuge in Lucerne. The monastery treasure, archive and library were also temporarily transferred there. The monastery remained undisturbed, but war taxes, confiscations and damage to the collatures caused losses of around 100,000 guilders. Muri, which was now the richest abbey in Switzerland, was soon able to make up for this. From 1712 Bern was also involved in the sovereignty of the free offices. Around 1750 the convent had over 50 members. Prince Abbot Gerold Meyer placed the order in 1788 to build a new east and south wing. He reacted to the increasing pressure from Enlightenment circles to open the monastery school to broader sections of the population. The monumental building should provide enough space for a school and library, and the establishment of a seminary was planned. In 1798 the building shell was completed. The planned new construction of the west wing and the church towers could no longer be carried out because the political events rolled over.

Decline and suspension

The French invasion swept away the old order. In March 1798 the prince went into exile and the convent renounced his sovereign rights on his behalf. The government of the new Helvetic Republic placed the monastery under state administration and ordered an inventory . In August, the members of the convention had to take an oath on the constitution. The abbey had to pay high war taxes and extensive requisition services. In addition, between January and September 1799, in the early phase of the Second Coalition War , 5500 French soldiers were accommodated and fed. In anticipation of the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss , the Principality of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen took almost the entire Muri rule on the Neckar in possession on November 2, 1802 (the later Oberamt Glatt ), a small part went to the Duchy of Württemberg . Gerold Meyer lost his title of prince, the financial loss totaled 950,000 guilders. Although the abbey tried to obtain appropriate compensation through legal channels, it was not until 1830 that the small sum of 70,000 guilders was settled.

In the canton of Aargau , which was established in 1803, the monasteries were again allowed to manage their goods freely, on the other hand, the farmers could buy their way from interest and tithes. In order to at least partially compensate for the considerable financial damage, the abbey sold the Thurgau dominions of Sandegg and Eppishausen in 1807. The federal treaty signed in 1815 expressly guaranteed the continued existence of the monasteries. In 1830 liberal forces came to power who wanted to push back the influence of the Catholic Church, which was considered hostile to the state. Seven liberal cantons, including Aargau, passed the Baden Articles in 1834 . The church was placed under state control, while the monasteries had to support the school system and the poor financially. The Muri Abbey, which at the time had assets of three million francs and had 80 employees, had to draw up an extensive inventory. The cantonal government presented on 7 November 1835, the abbey under state administration and forbade the reception of novices. Only after troops from Aargau had occupied the Freiamt did the clergy swear an oath on the constitution on November 30th. The administrator Rudolf Lindenmann sold the remaining monastery goods, some of them below their value.

On January 10, 1841, after the adoption of a new constitution, which had been clearly rejected in all Catholic districts, an armed uprising broke out in Freiamt , which the government troops quickly put down. The cantonal government accused the monasteries, especially Muri, of instigating the uprising. At the request of Augustin Keller , the Grand Council decided on January 13th to repeal it immediately. Colonel Friedrich Frey-Herosé (who later became Federal Councilor ) received the order to implement the decision. He restricted the monks' freedom of movement and on January 25th ordered them to leave the canton within 48 hours. Abbot Adalbert Regli stayed behind with four monks for a few days to arrange the transfer of the monastery property. On February 3, he was the last to leave Muri.

The Aargau monastery dispute led to domestic and foreign political tensions. Prince Metternich , the Austrian State Chancellor, even considered military intervention. Finally, the canton of Aargau agreed to a compromise in 1843 and allowed the women's monasteries again, but the men's monasteries remained permanently closed. In February 1841, the expelled convent accepted an offer from the canton of Obwalden, whereupon several friars moved to Sarnen in November 1841 to teach at the college. The Benedictines ran it until the secularized canton school in Obwalden was founded in 1974, and from 1868 to 2000 they also ran an affiliated boarding school . Until the end of the school year 2012/13, friars were part of the teaching staff of the canton school. From September 1843 Abbot Adalbert Regli conducted negotiations with Metternich to take over the vacant Augustinian canon monastery in Gries near Bozen . In June 1845 the first friars moved and founded the Muri-Gries Abbey , which is still a member of the Swiss Benedictine Congregation today.

Further development

The first service in the monastery church did not take place again until St. Martin's Day (November 11th) 1850. The Roman Catholic parish of Muri recognized the monastery church as the second parish church in 1863. However, it remained in the possession of the canton, which only made the most necessary repairs. After parts of the stucco ceiling fell down in 1928, an interior restoration was carried out for the first time from 1929 to 1933. The parish and canton signed a return contract in 1939; the ceremonial handover took place on January 13, 1941, exactly one hundred years after the monastery was closed. The first comprehensive exterior restoration of the monastery church took place between 1953 and 1957, a second between 1995 and 1997. In 1960 the parish established a small hospice in the convent wing; Since then, individual Benedictines have again been present in Muri and have taken on pastoral tasks in the region.

After the monastery was closed, there were numerous plans to use the vacant buildings. The cantonal teachers' seminar was to be set up in the spacious east wing , but in 1846 the Grand Council decided in favor of the Wettingen monastery, which had also been closed . In 1851 the German publisher Joseph Meyer intended to move his Bibliographical Institute from Hildburghausen to Muri. The negotiations failed a year later after the cantonal government announced that it wanted to set up a psychiatric clinic (a project that was ultimately realized in Königsfelden). In 1861 a cantonal agricultural school was opened. It never really got a foothold and had to be closed in 1873 due to insufficient interest from farmers. Projects for a sugar factory and machine embroidery also failed. In November 1883, the Grand Council approved the reconstruction of the east wing. A cantonal nursing home "for disabled and frail adults" was created, which was opened in September 1887 and, when completed, was to offer space for 340 people.

In 1843 the Progymnasium district school began teaching in the south wing . It was the only school of its kind in Aargau that was directly subordinate to the canton and not, as is usual, a community association. The liberal government feared that the predominantly conservative municipal authorities in the Muri district would otherwise influence school material. It was not until 1976 that the Muri district school was given equal status by decree, and a municipal association was established two years later. In 1851 the municipality of Muri decided to merge the primary school, which was spread over three buildings . Initially, the plan was to move to the office building , but the project came to nothing. In 1857, the municipality decided to use the convent wing instead, and the move was completed a year later. On the ground floor of this building, in the former monastery kitchen, there was a cheese dairy from 1868 to 1897 . From 1847 to 1876 there was a "poor welfare and work institution" in the Singisen wing. It was replaced by the St. Martin retirement home in 1900 , which used the building until 1991 and then moved into a new building in the neighborhood. The monastery pharmacy in the south wing, which had existed since 1705 and had been run by tenants since 1839, moved to the Singisen wing in 1862 and was closed in 1895; the 18th century furnishings have been exhibited in the National Museum in Zurich ever since .

At the beginning of February 1871 the French Bourbaki army crossed the border and was interned . On February 7, 970 of the approximately 87,000 soldiers were brought to Muri. The monastery served as accommodation, and the population donated money and clothing. By the end of the internment on March 13th, 22 soldiers had died of typhus , a memorial plaque on the parish church commemorates this. On August 21, 1889, a fire broke out in the attic of the east wing for reasons that were never clear . All inmates of the care facility could be rescued in time. Aided by stored wood and strong winds, the east wing burned out completely. The flames spread to the abbot's chapel and the sacristy, which were irreparably damaged and then demolished. A spread to the south wing and the choir of the monastery church could be prevented. 43 fire brigades from four cantons were on duty for up to five days as the fire kept flaring up. The cantonal fire insurance institute almost went bankrupt and was only able to avert it with 25% higher premiums. The east wing received a temporary roof that lasted a hundred years.

The canton decided not to restore the nursing home and offered the community the fire ruins for sale. When the community assembly declined this offer, the Grand Council sold the building to a consortium that promised the settlement of industry. Neither a cigar nor a canning factory was built. In 1897 a German brewer expressed his interest, but moved to the USA after the contract was signed . A charitable foundation acquired the east wing from the bankruptcy estate in 1899 and had it repaired. She ran an old people's asylum, a language school and a home for orphans. An association bought the east wing from the foundation in 1908 and set up a nursing home that started operations in 1909 and is still in operation today. In 1938 a functional building was added to the north end of the east wing (modernized in 2009). At the end of the 1950s, the nursing home wanted to build a second extension that would have flanked the monastery church on its north side. The municipal council approved the project, but the cantonal government approved a complaint submitted by the parish for monument preservation reasons.

Cultural influence

According to the Acta Murensia, there was a monastery school in Muri from the beginning . It limited itself to training its own offspring and never had more than twelve students at a time. The pupils' families had to pay for books and school supplies themselves. In addition to the Latin schools in Bremgarten and Mellingen , the monastery school was the only place in the Free Offices where higher education was provided. For a long time it was the only educational establishment in Muri. A village school did not open until 1735, when the abbey donated 2,000 guilders for this purpose and claimed the right to elect the schoolmaster. Due to political pressure, the abbey had to open the convent school to external students at the beginning of the 19th century. It turned into a grammar school with 40 to 50 students, but was closed in 1835 by order of the canton.

The monastery library goes back to the first head of the monastery, Reginbold. The Acta Murensia contain a list of the books he acquired. In addition, the monks Nokerus and Heinricus are mentioned by name as the first scribes of the scriptorium . Over the centuries, the book inventory grew despite fires and warlike events. In 1609, Abbot Johann Jodok Singisen had the vestibule of the monastery church extended and the library set up in the new room (the construction was canceled again in 1810 after the library had moved to the south wing). At the same time, Singisen opened a bookbinding shop and, in 1644, a printing shop . The latter remained in operation until 1799 when the printing press was confiscated and brought to Zurich. While the monastery archives were transferred to the Aargau State Archives after it was abolished, the Benedictines were left with over half of the codes . They were initially kept in Gries and brought to Sarnen in 1914 to the college's archives. The other codes are in the possession of the Aargau Cantonal Library .

The abbey produced some outstanding artists. These include the poet Konrad von Mure (approx. 1210–1281) and the painters Johann Caspar Winterlin (approx. 1575–1634) and Leodegar Kretz (1805–1871). Historiography was very important , starting with the Acta Murensia. From around 1500 the collection also included the Chronicon Murense , which was created in Engelberg in the 12th century and contained a copy of the imperial chronicle . Based on this, the historian Aegidius Tschudi wrote a monastery chronicle in the 1530s. His nephew Dominikus Tschudi created a genealogy of the Habsburgs using the same sources , Augustin Stoecklin created various collections of sources and Prince Abbot Fridolin Kopp also conducted historical research. The most important chronicler is Father Anselm Weissenbach, who wrote a monastery history between 1683 and 1693. His work formed the basis for the most extensive historical work to date, which Father Martin Kiem published in two volumes in 1881 and 1891. The most important work in the monastery library is the Muri Easter play . This fragmentary manuscript from the middle of the 13th century was discovered in the cover of a Vulgate edition in 1840 and is considered the oldest known sacred drama in German rhymes.

Only a fraction of the once extensive church treasure that the abbey acquired or received as a gift remains in Muri. The abbey suffered its first losses in 1798, when the financial difficulties of the Helvetic government melted down a considerable number of objects. In 1803, the canton of Aargau returned part of the property that had been confiscated at the time. Before and after the abolition of the monastery, the monks withdrew numerous objects from the state and brought them to Sarnen. The authorities had the rest transported to Aarau and stored. In the following years, the canton distributed cult devices to various Aargau parishes, including Muri. The rest of the confiscated church treasures were sold to art dealers between 1844 and 1851. In this way, the objects came into the possession of museums, private collections and the papal curia .

Coat of arms and seal

From around 1480 the convent had a coat of arms showing a crowned golden snake in a blue field. Abbot Johannes Feierabend introduced its own coat of arms for the abbey in 1508. Derived from the Latin origin of the place name Muri (murus) , a three-row, black jointed wall with three battlements is depicted on it. From 1930, the municipality of Muri had the coat of arms of the former abbey, but in 1972 it changed to a two-row wall based on a representation from 1618. The older version remains unchanged today as the coat of arms of the Muri district.

The oldest surviving seal is that of Abbot Arnold (from 1223). The abbot seals subsequently changed when each new monastery head took office. They showed a figurative representation of the respective abbot. From the term of office of Abbot Georg Russinger in the first half of the 15th century, the heraldic aspect was weighted more and more, until finally Jakob Meier broke with tradition completely in 1585 and limited himself to a coat of arms with an inscription.

Monastery complex

St. Martin monastery church

Exterior

The geostete monastery church is dedicated to Saint Martin of Tours ordained and is in the angle between the cloister and the east wing. It is 60 meters long and at the transept up to 31 meters wide. Over the centuries it has outwardly grown into a unity of Romanesque , Gothic and Baroque , characterized by cubic rigor, rich structure and diverse gradations. The oldest parts go back to the middle of the 11th century; it concerns the substructure of the two church towers , the walls of the transept and the choir and the crypt .

The building consists mainly of white plastered quarry stone masonry , in addition there are house stones in places . A variety of wall openings structure the structure. The octagon has large thermal baths , the choir has narrow round-arched lights, the transept has a late Gothic tracery window and a Romanesque blind arcade . The north and south towers on the west facade (both built in 1558) are each 32 meters high up to the eyelashes . The 25 meter high dome above the octagon is also characteristic . This central dome building, the largest of its kind in Switzerland, is crowned by a ball on which a trumpet angel stands. An eight-sided roof turret rises above the crossing of the transept, built in 1491 , which bears the Swiss German name "Güggelturm" because of the cock at the top .

inner space

The low, frescoed confessional church can be reached through the main portal in the west . On the sides are the foundations of the two church towers and three of the original eight confessionals . A large arch forms the transition to the central octagon , the work of the Ticinese plasterer Giovanni Battista Bettini. The room was framed in the roughly square floor plan of the nave. In this way, four small rooms in the diagonal axes and two larger side rooms were created. The star vault of the dome rests on the beams without an attic or tambour . A round All Saints Day motif decorates the center of the dome, the dome wraps contain depictions of Benedictine missionaries. There are also other paintings over the arched apexes connected to a continuous cornice . All ceiling paintings are by Francesco Antonio Giorgioli . Under the floor of the octagon there are graves with the remains of the monastery founders Ita of Lorraine and Radbot and of Abbot Johann Jodok Singisen .

To the east of the octagon is the crossing (also known as the monk's choir), which is three steps higher. Narrow passages lead to the side arms of the transept, in which chapels have been set up for Our Lady (north) and St. Benedict of Nursia (south). Six steps lead from the crossing to the high choir adjoining to the east, which has a star vault. The ceilings of the crossing, the high choir and the side chapels are painted with other frescoes by Giorgioli. Under the floor of the high choir and the transept is the Romanesque crypt , a three-aisled hall supported by six columns with groin vaults . You can access it through narrow corridors from the transept chapels.

Furnishing

With a few exceptions, today's interior is in the Rococo style and was created between 1743 and 1750. These works, commissioned by Prince Abbot Gerold Haimb, come mainly from the Fürstenberg court carpenter Matthäus Baisch and the Allgäu painter Franz Joseph Spiegler , as well as various regional artists Trains. In and next to the octagon there are six altars, which vary greatly in size and proportion. The largest are the Leontius Altar in the north and the Benedict Altar in the south side room; they contain the relics of two catacomb saints brought from Rome . In the northeast and southeast niches are the Petrus altar and the Descent from the Cross. On the crossing pillars to the left and right of the choir arch are the Holy Cross and the Michael altars. The pulpit with various carvings and a funnel-shaped raised pulpit basket is attached to the wall between the Leontius and Petrus altars. A donor memorial hanging as an epitaph on the wall between the Descent from the Cross and Benedict Altar reminds of Ita and Radbot, the monastery's founders.

A choir grille , created by the Constance locksmith Johann Jakob Hoffner, separates the dome from the adjoining monks' choir. The different patterns are arranged in such a way that a three-dimensional impression is created. The two-part choir stalls in the monks' choir are the work of the local carver and draftsman Simon Bachmann. It is one of the most important Swiss sculptures of the 17th century. The high altar , stylistically at the transition from the Regency style to the Rococo, occupies the entire east wall of the high choir. It has less of an effect due to its architecture (for example the columns are of different heights), but more due to its numerous gold-plated carvings that decorate the blue and white marbled links. On the side walls of the high choir are the abbot's throne and the celebrant seats. The armchairs stand on low parquet steps in front of carved beams, which are divided into three by pilasters .

Organs

The monastery church has five organs of different sizes. The "Great Organ" is located on the western gallery above the confessional church. It was built by Thomas Schott between 1619 and 1630 and has 34 registers . The company Orgelbau Goll cleared out the case completely in 1919/20 and changed the disposition fundamentally, as the organ was considered out of date according to the zeitgeist of the time. The restorer Josef Brühlmann and the organ builder Bernhardt Edskes von Metzler Orgelbau reconstructed the large organ between 1965 and 1972, taking care to restore the original condition wherever possible.

The Epistle organ with 16 registers, built in 1743 by Joseph and Victor Ferdinand Bossart, stands on the gallery above the altar of the Descent from the Cross. In the same year, father and son Bossart also built the gospel organ with eight registers. Both organs are almost identical in appearance, the differences are marginal. There are also two transportable small organs in the choir, a positive and a shelf . These are true-to-original reproductions of two small organs from the 17th and 18th centuries, which Bernhardt Edskes made in 1992.

Bells

Eleven church bells hang in the towers of the monastery church . The jubilee or Leontius bell from 1750 is the largest. It is the only one in the north tower and weighs around 4,300 kg with a diameter of 190 cm. The reliefs show the Annunciation, St. Benedict , the coat of arms of Prince Abbot Gerold Haimb and St. Martin with a beggar. In 1907 it was cast in the H. Rüetschi foundry in Aarau . It is the only one not to be rung manually.

Six bells can be found in the south tower. The oldest, the angelus bell from 1551, weighs around 2200 kg with a diameter of 155 cm; the relief shows twice the coats of arms of the abbot Johann Christoph vom Grüth and the convent. Three more bells date from 1679. The Vespers bell (1100 kg, 125 cm) has a relief with St. Sebastian and the coat of arms of Abbot Hieronymus Troger . The storm and fire bell (550 kg, 95 cm) depicts St. Michael , surrounded by angels and the coat of arms of the abbot and the convent. An unnamed bell (130 kg, 67 cm) depicts the Saints Agatha , Katharina , Antonius and Hieronymus . The festival bell (200 kg, 65 cm) with the coat of arms of Prince Abbot Ambrosius Bloch , St. Wendelin and the Mother of God dates from 1750 . The Brother Klausen bell from 1977 (360 kg) replaced the plague bell from 1827, which is now in the cloister.

The "Güggelturm" has two bells. The older one with a diameter of 96 cm was cast at the end of the 15th century. The younger (66 cm) dates from 1602; Depicted as a relief are the coat of arms of Abbot Johann Jodok Singisen and the convent, St. Martin, Our Lady and the crucified. Finally, two more bells hang in the ridge turrets of the two side chapels. The bell on the Leontius Chapel (46 cm) dates from 1647 and has reliefs of Saints Martin and Leontius as well as the Mother of God. The bell on the Benedict Chapel (43 cm) was cast in 1695, the coat of arms of Prince Abbot Plazidus Zurlauben is shown .

Convent wing and Singisen wing

The convent wing surrounds the cloister on three sides. The former chapter house , which has served as a sacristy since 1890, is located in the east wing, which was rebuilt in 1601 . The hall has a central column made of stucco marble and a ceiling decorated with acanthus tendrils, both built in 1707. The polygonal apse on the east wall contains an altar for Maria Magdalena from 1759, which stood in the crypt until 1933 (the previous altar was removed around 1890). In 1957 Baroque frescoes from the second half of the 17th century were exposed on both sides, depicting the crucifixion and the lamentation. In the same year the vestry cupboards were put together from older components (around 1700).

The west wing of the convent wing, built in 1604, contains a vaulted cellar that was once used to store wine. In 1685/86 the south wing of the convent wing was built. Its facade has 13 axes; four axes that led to the Lehmannbau were broken off in 1867. Modifications in the years 1899/1900 and 1963–1966 led to further major changes in the external appearance. On the ground floor is the former kitchen, a two-aisled hall with groined vaults and five square pillars. A shell limestone fountain from 1788 stands on the wall. The ceiling of the corridor on the first floor of the south wing was created by the plasterer Giovanni Battista Bettini. At the western end of the corridor is the former refectory . Inside there is a dome stove created in 1762 , the frieze tiles of which were painted by Caspar Wolf .

The Singisen wing, named after Abbot Johann Jodok Singisen, was built in 1610 and completely rebuilt in 1692/94. The elongated, three-story building is attached to the cloister at right angles and protrudes to the west. The plain-looking facade has 13 axes on the long side and two axes on the transverse side, divided by cornices . The portal wall is a square basket arch, flanked by Tuscan pilasters and a segmented gable . The south wall is decorated with Zurlauben's coat of arms, the underside of the roof gable with volute consoles and diamonds.

Cloister

The cloister was rebuilt in 1534/35 under Abbot Laurentius von Heidegg . It is made up of parts of the three adjoining buildings (monastery church, convent wing, Singisen wing). The ceiling of the west wing is stuccoed with acanthus medallions, the east wing has a beamed ceiling (replaced the badly damaged stucco in 1956), the south wing a groin vault. The connecting element of the three differently designed wings are the 19 three-part lancet windows facing the inner courtyard . They are adorned with a total of 57 cabinet disks , which are among the most important works of Renaissance glass painting in Switzerland.

The window arches were initially unglazed. From 1554, Abbot Johann Christoph vom Grüth had them decorated with cabinet disks, which were donated by friendly monasteries, the federal umbrella locations of the abbey, neighboring towns, magistrates and foreign envoys, according to the custom of the time. The discs are painted with biblical and secular motifs. When the monastery church was rebuilt in 1695, most of the north wing was demolished, which meant that the existing windows were lost. After the monastery was closed, the cabinet disks were removed, brought to Aarau and exhibited there in the government building from 1869 . From 1897 they adorned the Aarau Art and Craft Museum. In 1957, the panes were brought back to Muri and inserted into the restored window arches at their original location.

Loreto Chapel

When the north wing of the cloister was demolished, three yokes remained in the north-western corner. Abbot Plazidus Zurlauben had a Loreto chapel built there, which he consecrated in 1698. The small and artistically simple chapel room contains a blue altar porch, the ribbed vault is also painted blue with the representation of the firmament. The keystones are carved with the coats of arms of the abbot and the monastery, the altar has a low cartouche top . Behind the lattice is a wooden statue of Our Lady flanked by four angels.

The chapel is of particular importance as an entrance to the family crypt of the former Austrian ruling house Habsburg-Lothringen . Traditional burial sites such as the Imperial Crypt in Vienna were denied to the Habsburgs for decades after they were deposed. In March 1970 Archduke Rudolph signed a contract with the Catholic parish of Muri to use the Loreto Chapel as a new burial site. The crypt space required for this was newly laid out, as there was no cellar below the Loreto Chapel. The funeral there began in 1971 with the heart burial of the last Emperor Karl I, who died in 1922.The heart urn is located in a brick stele behind the altar, on the back wall of the chapel, and since 1989 has also been the heart urn of the last Empress Zita von Bourbon-Parma . Archdukes Robert (1996), Rudolph (2010) and Felix (2011) found their final resting place in the crypt itself . The Muri Monastery is thus the oldest known and at the same time the youngest burial place of its donor family. A bronze bust placed in the cloister has also been a reminder of Emperor Karl since 2010.

Lehmannbau (east and south wing)

The largest and at the same time youngest building in the monastery complex is the “Lehmannbau”, built in the early classical style, named after the Fürstenberg court architect Valentin Lehmann. In 1789 he estimated the costs for the east and south wings at 353,676 guilders (a west wing that was also planned was never realized). The construction was partly financed by repaying a bond from the Fürstenbergers to the abbey. Lehmann was in charge of the construction and awarded various commissions to artists from Switzerland and southern Germany. For example, Peter Anton Moosbrugger carried out the stucco work in the ballroom. When the construction work had to be stopped in 1798, the costs had risen to around 570,000 guilders. Nothing has been preserved from the equipment from that time. After the fire in 1889, the east wing was given a temporary roof. A comprehensive exterior restoration began in 1985; The roof, the facade and the windows were reconstructed according to Lehmann's original plans. The work was ceremonially completed on August 21, 1989, exactly one hundred years after the fire.

The east wing of the Lehmann building is four stories high and extends over a length of 218 meters. The east-facing front with 49 axes is the longest classicist facade in Switzerland. It is characterized by rigorous simplicity and regularity, with risalits and different roof shapes setting accents. A cornice separates the two lower floors from one another, while on the other hand, square pilaster strips combine them into one unit. The two upper floors are grouped together by pilasters (double at the corners). The main portal is framed by an aedicula with Doric columns; on it sits a triangular gable with acroteria . The central projection takes up nine axes, of which the three central ones protrude again and are also arched. In this area the windows have pointed arches , in the three central axes they are also suspected . All other windows are rectangular and rest on brackets . The 65-meter-long south wing has three floors and is very simply designed. The slightly protruding corner pavilions are lined with square pilaster strips, the brackets are completely missing in the rectangular windows. A narrow arch-shaped passage leads through the middle of the south wing, the outer portal of which is framed by two pilaster strips with acroteria and a triangular gable.

Fountains and gardens

In the cloister courtyard, between the convent wing and the south wing, is the Martinsbrunnen. It was commissioned by Abbot Johann Jodok Singisen in 1632 and originally stood in the adjacent convent garden. The figure, a representation of the patron saint of the monastery, Martin von Tours, was created by the Alsatian sculptor Gregor Allhelg . The fountain was moved to Lucerne in 1881 , and the figure came into the possession of the Keusch family from Boswil. The fountain basin was reconstructed in 2008 on the initiative of the Friends of the Muri Monastery Church. In the course of this, Josef Ineichen restored the original fountain column and the figure.

A park in the style of an English landscape garden extends east of the monastery complex . The area in front of the central projection of the east wing, the former abbot garden, is designed as a baroque garden . The area was previously used for agriculture and was the location of the monastery stables. Over time, it turned into a publicly accessible green area with old trees. The park has been wheelchair accessible since the renovation in 2011. To the north of the monastery church is the kitchen garden, which has been attested to on views of the monastery since 1609. Since the redesign in 2001/02, it has served its original purpose again, namely the cultivation of useful plants. The ProSpecieRara Foundation planted bushes with old berry varieties. The convent garden at the Singisen wing was redesigned in 2003/04. The historical spatial order of the baroque complex, as it existed until the monastery was closed in 1841, was restored.

Demolished building

On the north side of the monastery area was the "women´s house", in which the female guests of the monastery lived. It was built in 1703/04 and externally resembled the Singisen wing; in 1787 it was stuccoed by Peter Anton Moosbrugger. After the abolition of the monastery, the building served as an educational institution, and from 1912 it housed the Hotel Löwen. In 1949 the women's house was demolished to make room for an operating building for the nursing home. The tavern sign and a fragment of the paneling (today in Sursee and Aarau) have been preserved. In 1697 and 1698 two monastic storage buildings were built on the street east of today's Lehmann building (referred to as “Vordere Föhn” and “Hintere Föhn”). After significant renovations in the first half of the 20th century, only the foundation walls have been preserved, each with a relief of the coat of arms of Abbot Plazidus Zurlauben. To the south of the cloister complex, Zurlauben had an existing building rebuilt and expanded in 1694. It contained rooms for servants and craftsmen, sickrooms, a chancellery, a mill and a bakery. The building, which cost 22,400 guilders to build, was demolished in 1789 to make room for the south wing of the Lehmann building.

use

Music and art

In 1969, on the initiative of the then Aargau government councilor Leo Weber, the St. Martin Cultural Foundation (Murikultur Foundation since 2011) was established. Its aim is to promote the cultural offer inside and outside the monastery. A dozen permanent employees and numerous volunteers organize around 100 events every year. Since 2011, Murikultur has been recognized by the cantonal government as a cultural institution of at least cantonal importance and receives operating contributions for it. The association "Friends of the Muri Monastery Church", founded in 1992, works closely with Murikultur. Its purpose is to maintain the Benedictine tradition in the monastery church and to preserve the church.

The octagon of the monastery church has been performing numerous classical concerts since 1971. With its five organs and four galleries for additional musicians, the church is particularly suitable for scenic oratorios . The Austrian church musician Johannes Strobl has been the artistic director of the concert series, which lasts from May to September, since 2001 . In the winter half-year chamber music and symphonic performances take place in the ballroom of the east wing . Concerts in the refectory serve to promote young talents, and there are also occasional concerts and theater performances in the courtyard of the monastery.

Two museums are accessible from the cloister. The monastery museum, opened in 1992, is located in the east wing next to the sacristy. A part of the former church treasure of the abbey, which was divided up and scattered in 1841 when the monastery was closed, is exhibited there. The collection includes a silver tabernacle , vestments , monstrances , chalices and other liturgical items. The "Museum Caspar Wolf" in the Singisen Wing is the largest permanent exhibition with works by the painter Caspar Wolf from Muri , who is considered a pioneer of high mountain painting . Oil paintings, watercolors, gouaches, chalk drawings, sketches, engravings and reproductions can be seen. It was opened in the refectory in 1981, was located in the vaulted cellar of the west wing from 1997 and moved into its current exhibition space in January 2018. The "Singisenforum", opened in 1998 on the ground floor of the Singisen wing, specializes in contemporary art; Every year there are changing exhibitions with works by regional artists.

Other users

The nursing home opened in 1909 in the east wing of the Lehmann building now appears under the name “Pflegeimuri”. Almost 300 employees look after around 200 residents in need of care. The nursing home, which also includes departments for the severely disabled and dementia patients, is the second largest employer in Muri. The sponsorship is an association with around 600 members.

The convent wing was the only primary school location for almost a century . The population growth and the expansion of the educational offer resulted in increasing space problems. In 1954 the first new school building was opened, followed by four more. In 1985 the district school also moved out of the south wing. Today eight primary school classes are still taught in the convent wing. The south wing is shared by the Muri municipal administration, the district court , the district office and, since 2011, the public prosecutor's office for the Muri and Bremgarten districts. Since the retirement home St. Martin moved out in 1991, the Singisen wing has been used by some municipal offices and the Benedictine hospice. The public library with 17,000 media is located on the top floor of this building.

The Murensia collection has existed in the convent wing, in the former room of the Benedictine hospice, since November 2009. This specialist library, which is supported by the universities of Zurich , Friborg and Lucerne , among others , is intended to bring together publications and sources on the Muri Monastery and Freiamt as well as scientific tools in one place. With the help of the collection, with a view to the 1000th anniversary of the monastery in 2027, the history of the abbey is to be systematically processed and completed (most of the most recent scientific works date from the 1960s).

legend

A legend known in Freiamt tells of the "Stifeliryter" (boot rider). He is an irascible, hypocritical and greedy conductor (administrator) of the Muri monastery, who harassed the rural population on horseback and in big boots. One day he got involved in a lawsuit with a group of peasants, whereupon the governor had to judge. When the Stifeliryter swore a blasphemous perjury in court, he fell dead instantly. Since then he has been making the area unsafe as a fire-breathing ghost figure riding on his white horse.

literature

- Rupert Amschwand, Roman Brüschweiler, Jean-Jacques Siegrist: Muri. In: Helvetia Sacra. Vol. III / 1, 1986, pp. 896-952.

- Peter Felder, Martin Allemann: The Muri Monastery. In: Swiss Art Guide GSK , Volume 980, Bern 2015.

- Peter Felder: The Muri Monastery . Ed .: Society for Swiss Art History . Swiss art guide, volume 692 . Bern 2001, ISBN 3-85782-692-4 .

- Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton Aargau . Ed .: Society for Swiss Art History. Volume V, Muri District. Birkhäuser, Basel 1967.

- Bruno Meier : The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey . here + now, Baden 2011, ISBN 978-3-03919-215-1 .

- Dieter Meier: The organs of the monastery church Muri - history, description, organ builder . here + now, Baden 2010, ISBN 978-3-03919-201-4 .

- Hugo Müller: Muri in the Free Offices, Volume 2: History of the Muri Community since 1798 . In: Historical Society of the Canton of Aargau (Ed.): Argovia . tape 101 . Sauerländer, Aarau 1989, ISBN 3-7941-3124-X , doi : 10.5169 / seals-7533 .

- Pascal Pauli: Monastery Economics, Enlightenment and “Parade Buildings”. The new building of the Muri monastery in the 18th century . Chronos, Zurich 2017, ISBN 978-3-0340-1358-1 .

- Jean-Jacques Siegrist : Muri in the Free Offices, Volume 1: History of the area of the future municipality of Muri before 1798 . In: Historical Society of the Canton of Aargau (Ed.): Argovia . tape 95 . Sauerländer, Aarau 1985, ISBN 3-7941-2441-3 , doi : 10.5169 / seals-75040 .

Web links

- Anton Kottmann: Muri (monastery). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Muri monastery . In: Bibliography of Swiss History in the Swiss National Library

- Main page of Muri-Gries Monastery at www.muri-gries.ch

- Murikultur Foundation

- Friends of the Muri Monastery Church

- Nursing home website

- Aerial view of the monastery

Individual evidence

- ^ Jean-Jacques Siegrist: Muri in the Free Offices, Volume 1. P. 48-50.

- ^ Jean-Jacques Siegrist: Muri in the Free Offices, Volume 1. P. 53–56.

- ^ Jean-Jacques Siegrist: Muri in the Free Offices, Volume 1. pp. 56-58.

- ^ Jean-Jacques Siegrist: Muri in the Free Offices, Volume 1, p. 75.

- ^ Jean-Jacques Siegrist: Muri in the Free Offices, Volume 1. P. 35–36.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. Pp. 19-20.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. P. 23.

- ↑ Urban Hodel, Rolf De Kegel: Engelberg (monastery). In: Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz ., Accessed on March 20, 2014.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. P. 101.

- ↑ a b Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. Pp. 20-21.

- ^ Jean-Jacques Siegrist: Muri in the Free Offices, Volume 1. P. 84-85.

- ^ Jean-Jacques Siegrist: Muri in the Free Offices, Volume 1. P. 92-98.

- ^ Jean-Jacques Siegrist: Muri in the Free Offices, Volume 1. S. 153.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. Pp. 31-32.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. P. 48.

- ^ Jean-Jacques Siegrist: Muri in the Free Offices, Volume 1. pp. 77-79.

- ^ Jean-Jacques Siegrist: Muri in the Free Offices, Volume 1. pp. 136-140.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. Pp. 33-35.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. Pp. 37-38.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. P. 29.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. Pp. 63-64.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. P. 66.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. P. 68.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. Pp. 72-73.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. P. 75.

- ↑ a b Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. P. 81.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. P. 85.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. P. 39.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. Pp. 85-89.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. P.56.

- ↑ a b Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. P. 40.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. Pp. 103-105.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. Pp. 89-92.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. Pp. 93-96.

- ↑ a b Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. P. 113.

- ^ Hugo Müller: Muri in the Free Offices, Volume 2. S. 9.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. Pp. 115-116.

- ^ Hugo Müller: Muri in the Free Offices, Volume 2. P. 36–43

- ^ Hugo Müller: Muri in the Free Offices, Volume 2. pp. 46-48.

- ↑ a b Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. Pp. 121-122.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. Pp. 136-138.

- ^ Hugo Müller: Muri in the Free Offices, Volume 2. P. 51-52.

- ^ Hugo Müller: Muri in the Free Offices, Volume 2, p. 198.

- ^ Hugo Müller: Muri in the Free Offices, Volume 2. P. 147–151.

- ^ Hugo Müller: Muri in the Free Offices, Volume 2. pp. 143-144.

- ^ Hugo Müller: Muri in the Free Offices, Volume 2. pp. 222-223.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. P. 145.

- ^ Hugo Müller: Muri in the Free Offices, Volume 2. P. 64–67.

- ^ Hugo Müller: Muri in the Free Offices, Volume 2. P. 68-72.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. P. 140.

- ↑ Hugo Müller: Muri in the Free Offices, Volume 2. P. 76-79.

- ^ Hugo Müller: Muri in the Free Offices, Volume 2. pp. 155–157.

- ↑ a b Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. Pp. 142-143.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. Pp. 47-48.

- ↑ Charlotte Bretscher-Gisiger, Rudolf Gamper: Catalog of the medieval manuscripts of the monasteries Muri and Hermetschwil . Urs Graf Verlag, Dietikon 2005, ISBN 3-85951-244-7 ( Online [PDF; 4.1 MB ]).

- ^ Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton of Aargau, district of Muri. P. 297.

- ^ Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton of Aargau, district of Muri. P. 404.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. Pp. 129-130.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. P. 55.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. Pp. 51-52.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. Pp. 128-129.

- ^ Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton of Aargau, district of Muri. Pp. 297-298.

- ^ Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton of Aargau, district of Muri. P. 215.

- ^ Joseph Galliker, Marcel Giger: Municipal coat of arms of the Canton of Aargau . Lehrmittelverlag des Kantons Aargau, book 2004, ISBN 3-906738-07-8 , p. 225 .

- ^ Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton of Aargau, district of Muri. Pp. 215-220.

- ↑ Peter Felder: The Muri Monastery. P. 12.

- ^ Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton of Aargau, district of Muri. Pp. 223-226.

- ↑ Peter Felder: The Muri Monastery. P. 13.

- ^ Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton of Aargau, district of Muri. Pp. 255-258.

- ^ Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton of Aargau, district of Muri. Pp. 258-260.

- ^ Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton of Aargau, district of Muri. Pp. 263-264.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. P. 31.

- ^ Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton of Aargau, district of Muri. Pp. 260, 266.

- ^ Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton of Aargau, district of Muri. Pp. 228-229.

- ^ Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton of Aargau, district of Muri. Pp. 271-276.

- ^ Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton of Aargau, district of Muri. Pp. 279-280.

- ^ Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton of Aargau, district of Muri. Pp. 289-291.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. P. 76.

- ^ Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton of Aargau, district of Muri. Pp. 267-270.

- ^ Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton of Aargau, district of Muri. Pp. 276-277.

- ↑ Dieter Meier: The organs of the monastery church Muri. Pp. 62-87.

- ↑ Dieter Meier: The organs of the monastery church Muri. Pp. 100-111.

- ↑ Dieter Meier: The organs of the monastery church Muri. Pp. 132-143.

- ^ Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton of Aargau, district of Muri. P. 357.

- ^ Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton of Aargau, district of Muri. Pp. 359-360.

- ^ Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton of Aargau, district of Muri. Pp. 358-359.

- ^ Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton of Aargau, district of Muri. Pp. 353-354.

- ^ Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton of Aargau, district of Muri. Pp. 367-372.

- ^ Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton of Aargau, district of Muri. Pp. 356-357.

- ↑ Murikultur Foundation, communication dated July 1, 2018.

- ↑ A brief overview of the Habsburgs and the Muri monastery. (PDF; 27 kB) (No longer available online.) Murikultur Foundation, archived from the original on January 23, 2015 ; Retrieved September 19, 2012 .

- ^ Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton of Aargau, district of Muri. Pp. 339-342.

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. P. 163.

- ^ Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton of Aargau, district of Muri. Pp. 363-366.

- ↑ Martinsbrunnen in the inventory of historical monuments of the Canton of Aargau

- ↑ The park of the pflegimuri. (PDF; 5.9 MB) (No longer available online.) In: Haustizytig May 2011 edition. Pflegeimuri, p. 5 , archived from the original on January 23, 2015 ; Retrieved September 19, 2012 .

- ↑ Redesign of the large kitchen garden, Kloster Muri / AG. (PDF) (No longer available online.) SKK Landschaftsarchitekten, archived from the original on April 16, 2016 ; Retrieved September 19, 2012 .

- ↑ Peter Paul Stöckli: The gardens of the Muri monastery. (Swiss Art Guide, No. 927, Series 93). Ed. Society for Swiss Art History GSK. Bern 2013, ISBN 978-3-03797-112-3 .

- ^ Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton of Aargau, district of Muri. Pp. 361-362.

- ^ Georg Germann: The art monuments of the canton of Aargau, district of Muri. P. 334.

- ↑ a b History of the Murikultur Foundation. (PDF; 122 kB) (No longer available online.) Murikultur Foundation, 2012, archived from the original on March 26, 2016 ; Retrieved September 19, 2012 .

- ↑ portrait. Murikultur Foundation, 2012, accessed on September 19, 2012 .

- ↑ a b Inspired. (PDF; 965 kB) (No longer available online.) Murikultur Foundation, 2012, archived from the original on March 4, 2016 ; Retrieved September 19, 2012 .

- ↑ 920 friends of the monastery donated two million. Aargauer Zeitung , July 6, 2012, accessed on September 19, 2012 .

- ^ Muri Monastery Museum - The sky before your eyes. Aargau Tourism, 2019, accessed on April 24, 2019 .

- ^ Museum Caspar Wolf. Murikultur Foundation, 2018, accessed April 24, 2019 .

- ↑ Muri 's most famous son gets a home: Museum Caspar Wolf opens in 2019. Aargauer Zeitung , January 16, 2018, accessed on April 24, 2019 .

- ^ Singisenforum. Murikultur Foundation, 2018, accessed April 24, 2019 .

- ↑ Organization. (No longer available online.) Pflegeimuri, archived from the original on February 3, 2012 ; Retrieved September 19, 2012 .

- ^ Hugo Müller: Muri in the Free Offices, Volume 2. pp. 144–146.

- ↑ Community schools . Muri Municipality, accessed December 3, 2013 .

- ↑ Bruno Meier: The Muri Monastery, History and Present of the Benedictine Abbey. P. 146.

- ^ Muri library. Murikultur, accessed December 3, 2013 .

- ↑ Murensia Collection. Research project History of Muri Monastery, accessed on September 19, 2012 .

- ↑ The Stifeliryter. Freiämter Sagenweg, accessed on September 19, 2012 .

- ↑ Hans Koch: Freiämter Sagen . In: Historical Society Freiamt (ed.): Our home . tape 52 . Walter Sprüngli, Villmergen 1981, p. 67-69 .

Coordinates: 47 ° 16 '31.3 " N , 8 ° 20' 18.8" E ; CH1903: 668,092 / 236440