Martin's Day

The St. Martin (also Saint Martin's Day or St. Martin , in Bavaria and Austria, Martini , of lat. [Festum Sancti] Martini 's "Feast of St. Martin") in the church year the feast of St. Martin of Tours on 11 November . The date of the required day of remembrance in the Roman general calendar , which is also found in the Orthodox calendars of saints, the Protestant calendar of names and the Anglican Common Worship , is derived from the burial of Bishop Martin of Tours on November 11, 397 . St. Martin's Day is characterized by numerous customs in Central Europe, including St. Martin's goose meal, St. Martin's procession and St. Martin's singing .

Roots of tradition

The different customs have their roots in two different occasions. It was not until the 19th century that the customs got their content related to the figure of St. Martin and the legends about him such as the division of the coat.

- In Christianity influenced by Byzantium , St. Martin's Day was at the beginning of Lent , which was celebrated before Christmas from the Middle Ages to modern times - in the Orthodox churches sometimes until today . The number of animals that could not be fed through the winter had to be reduced, and existing foods such as fat, lard and eggs that were not "suitable for Lent" had to be consumed. On the last day before the start of this fasting period, people were able to feast again - analogous to Carnival .

- In addition, St. Martin's Day was the end of the farming year, new wine could be tasted, it was the date for the cattle drive or the end of the grazing year and the traditional day on which the tithing was due. Taxes used to be paid in kind, including geese. On this day, employment, lease, interest and salary periods began and ended. Later, the day of St. Leonhard of Limoges , the patron saint of cattle, on November 6th was named for this. Land leases still often refer to martini as the start and end date, as the time corresponds to the start and end of the natural management period. Martin's day was therefore also called interest day .

The oldest layer of the Martins tradition, which existed regionally until around 1800, resulted from both motifs. On the eve of November 11th, the children's mores had their place, there were social celebrations with food and drink, at home or in the tavern, and Martin fires were burned, surrounded by fire customs such as jumping over the fire, dancing around the fire, blackening faces and Torch relay with straw torches. These customs were still largely spontaneous and disordered. In the 18th and 19th centuries there were also police bans on Martin fires. It was not until the 20th century that it became customary in the Rhenish carnival to proclaim the carnival session on November 11th.

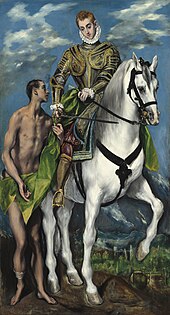

Today's research on customs observes that the emergence of the enlightened bourgeoisie and the urbanization movement since the 19th century led to the development of the spontaneous Martins tradition "into an urban and catechetical large-scale event with complex organizational structures", which then turned into an "economic" towards the end of the 20th century Functionalization and Commercialization ”could be. Spontaneous walks and lantern parades of the children were the initiative and organization of adults - schools, church parishes or municipalities - subjected. For the "construction of a Martin tradition", medieval saint legends are used and a continuity between the Middle Ages and the present is shown. Mainly the legend of the soldier Martin's coat sharing with a beggar became the motif of catechetical and educational efforts after the First World War , especially in the Rhineland. In Paderborn , a “Martin's Committee” was set up in the 1950s to organize the spontaneous activities observed by children in the city with the statutory objectives of “promoting charitable action and thinking and educating children to love their neighbor, and conveying suggestions for making torches , Lamps and lanterns ”. A prepared Christmas presents after the St. Martin's procession are made out of the heat. The refusal of military service of the Roman soldier Martin for religious reasons, reported by Martin's biographer Sulpicius Severus , does not play a role in Martin's custom; The focus is still on the mounted soldier in an officer's coat.

regional customs

Martin goose

The traditional Martinsgansessen ( also known as Martinigans or Martinigansl in Austria ) is particularly common today .

A historical attempt to explain this custom is based on the assumption that in times of feudalism , the origin was a feudal obligation due on Martin's Day , a levy called Martin's lap . Since this often consisted of a goose, the name Martin's goose was developed, and because Martin's Day was traditionally celebrated with a fair or a dance music evening, it made sense to make the goose for a feast and to eat it festively that evening.

Legends like to tell that the St. Martin's goose had its origin in Martin's life: against their own will and despite the reservations of the clergy, the people of Tours pressed for Martin to be ordained bishop. Ascetic and humble as he led his life, he considered himself unworthy of such a high office and therefore hid in a goose pen. The geese, however, chattered so excitedly that Martin was found and could be consecrated. According to another account, the citizens of Tours resorted to a ruse: a farmer went to Martin's hiding place and asked him to visit his sick wife. Helpful, as Martin was, he took his things and accompanied the farmer home. He probably looked pretty dirty - like he'd lived in a goose barn for a while. Another story goes that a chattering flock of goose waddled into the church and interrupted Bishop Martin during his sermon. Then this was caught and consumed.

Such legends have only been known since the 16th century. They are regarded as "secondary legends" ( etiologies ) that try to explain a custom in retrospect. The connection of the geese with the lease date of St. Martin's Day is seen in research as older than the legends.

In the bishop's chronicle of Lorenz Fries from 1546, a festive goose meal from Würzburg citizens is shown on St. Martin's night.

In Germany , the goose is traditionally eaten with red cabbage and bread dumplings or potato dumplings . A traditional custom when eating the St. Martin's goose is the goose poem .

Martiniloben as a culinary offer

In Gols , to or around St. Martin, the patron saint of the day is the state saint of Burgenland , the wine cellars were initially only open to wine growers and locals to taste the young wine. Tourist marketing began here around 1997. Today the Martiniloben is a multi-community event with significant tourism turnover.

Saint Martin's Parade

In many regions of Germany, Austria, Switzerland , Luxembourg as well as in East Belgium, South Tyrol and Upper Silesia , moves are common on St. Martin's Day. During the parades, children with lanterns move through the streets of the villages and towns. They are often accompanied by a rider sitting on a white horse who, wearing a red cloak, depicts St. Martin as a Roman soldier . In Bregenz this custom is called Martinsritt , in the Rhineland Martinszug and in Vianden (Luxembourg) Miertchen . The legendary gift of the coat to the beggar is also often reproduced. Martin's songs are sung during the parade , often accompanied by a brass band . The lanterns are often tinkered beforehand in primary schools and kindergartens.

The current form of the Martinszug, in which Saint Martin rides as a soldier or as a bishop, was created around the turn of the 20th century in the Rhineland, after there had already been light parades in the form of “noise parades with lights” or as an organized parade led by adults ( Documented from Dülken in 1867 ). In October 2017, an initiative of 73 Sankt Martin's associations applied for recognition of the tradition they cultivated as an intangible cultural heritage within the meaning of UNESCO . Today's St. Martin trains are mostly parish, school-oriented and catechetical. The role play of the “mantle division” accentuates the appeal for human help, which is to be conveyed to the participating children in retrospective recourse to the Martin legend.

There is often a big one at the end Martin's fire. Nowadays, children in some regions of West Germany receive a Stutenkerl (Westphalian) or Weckmann (Rhenish) made from yeast dough with raisins . In most regions (also often in West Germany), Stutenkerle / Weckmänner are an Advent pastry that is consumed on Christmas Eve / Day. The pipe stands (on both days) symbolically for a crosier. In some regions of West Germany there are Martin's squirrels. In southern Germany, little Martin geese made from biscuit or yeast dough, but also Martin croissants or pretzels are common. In parts of the Rhineland and Westphalia as well as the Ruhr area , the Sauerland and other parts of Germany, the children receive a “Martinsbrezel” - a pretzel made from sweet yeast dough, in some regions sprinkled with sugar.

The largest St. Martins parades in Germany with up to 8,000 participants take place in Worms-Hochheim , Kempen am Niederrhein, Essen-Frintrop and Bocholt . Nowadays, for organizational reasons, the trains also take place on other days around the actual festival day in some places, for example because there is only one Martin actor or only one brass band available for several district trains.

The custom is not limited to the German-speaking area. The German community in Stockholm organizes a St. Martin's parade, and the custom also exists in the Netherlands .

Martinssingen - Martinisingen

After the St. Martin's procession or on a slightly different date, St. Martin's singing is also practiced in many places , in which the children go from house to house with their lanterns or lanterns and sing to ask for sweets, pastries, fruit and other gifts. There are numerous local names for these Heischegänge, in the Rhineland for example Kötten , Schnörzen , Dotzen or Gribschen .

In East Friesland and other Protestant areas, this corresponds to martinis singing on the evening of November 10th. It refers to Martin Luther , whose first name, according to his baptism date on November 11th, goes back to Saint Martin of Tours (see name day ), and can be seen as a Protestant modification of the elements of Catholic tradition that were given a new meaning in the 19th century; now Martin Luther was celebrated as “the friend of light and the man of faith”, “de Pope in Rome de Kroon offschlog”. Martin von Tours songs were repackaged or rededicated to Martin Luther songs, the customs such as the lantern parades were linked.

Martin's blessing

Especially in Eastern Austria , the pastors bless the new wine ( Heuriger ), which is then served by the Heuriger hosts for the first tasting after this "Martiniloben".

Fur / nut mats

In some predominantly Protestant areas of southern Germany, such as in the Donau-Ries , on the Swabian Alb and in Central Franconia , the Pelzmärtel , also Pelzmartin or Nussmärtel , brings gifts on Martin's Day.

Friendship meal of Saint Martin

Since 1973 the construction industry association North Rhine-Westphalia e. V. organized a friendship meal with prominent speakers on Martin's Day. In total, the association's member companies have raised over 1.5 million euros for charitable purposes since the event was set up.

additional

see also: Martinswein

literature

- Martin Happ: Old and new pictures of Saint Martin: Customs and uses since the 19th century (= Cologne publications on the history of religion. Vol. 37). Böhlau, Köln / Weimar 2006, ISBN 3-412-05706-1 (also dissertation University of Cologne 2006; limited preview in the Google book search).

- Wilhelm Jürgensen: Martinslieder. Investigation and texts. M. &. H.Marcus, Breslau 1909 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- Annette Schneider: Study on children's parties at Martini and Nikolaus: examined using the example of selected locations in the Mansfeld region . Halle (Saale) 1994, DNB 947623299 ( dissertation Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg 1996).

- Karl Simrock , Heinrich Düntzer : Martinslieder. Marcus, Bonn 1846 ( digitized in the Google book search).

- Carl Clemen : The origin of the Martinsfest. In: Journal of the Association for Folklore 28, 1918, pp. 1–14.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Martin von Tours in the Ecumenical Lexicon of Saints

- ^ Manfred Becker-Huberti : Celebrations - Festivals - Seasons. Living customs all year round. Special edition, Herder Verlag, Freiburg (Breisgau) 2001, ISBN 3-451-27702-6 , p. 34.

- ^ A b c Manfred Becker-Huberti: Celebrations - Festivals - Seasons. Living customs all year round. Special edition, Herder Verlag, Freiburg (Breisgau) 2001, ISBN 3-451-27702-6 , p. 36.

- ↑ Dieter Pesch: The Martins Customs in the Rhineland. Change and present position. (Dissertation of February 6, 1970) Münster 1970, p. 29 ff.

- ↑ Dieter Pesch: The Martins Customs in the Rhineland. Change and present position. (Dissertation) Münster 1969, p. 59.

- ↑ Dieter Pesch: The Martins Customs in the Rhineland. Change and present position. (Dissertation) Münster 1969, p. 51 ff.

- ↑ Martin Happ: Old and new pictures of the holy Martin. Customs and uses since the 19th century. Cologne-Weimar-Berlin 2006, pp. 208, 214.

- ↑ Martin Happ: Old and new pictures of the holy Martin. Customs and uses since the 19th century. Cologne-Weimar-Berlin 2006, p. 215 f .; in Paderborn this is linked to the veneration of St. Liborius , who, according to an unsecured legend, is said to have been friends with Martin von Tours. In Westphalia the tendency was only adopted relatively late from the Rhineland.

- ↑ Martin Happ: Old and new pictures of the holy Martin. Customs and uses since the 19th century. Cologne-Weimar-Berlin 2006, p. 208.

- ↑ Wigand's Conversations Lexicon for all stands. Otto Wigand, Leipzig 1849, OCLC 299984559 , p. 582.

- ↑ Journal of the Association for Hessian History and Regional Studies: The customs from the legendary time of the Germans, namely the Hessians. 1st volume. Kassel 1867, p. 318.

- ↑ Stefan Kummer : Architecture and fine arts from the beginnings of the Renaissance to the end of the Baroque. In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. 4 volumes; Volume 2: From the Peasants' War in 1525 to the transition to the Kingdom of Bavaria in 1814. Theiss, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-8062-1477-8 , pp. 576–678 and 942–952, here: p. 586.

- ↑ Martiniloben: Important economic factor orf.at, November 11, 2017, accessed November 11, 2017.

- ↑ Miertchen

- ↑ Miertchen

- ^ Burghart Wachinger : Martinslieder. In: author's lexicon VI, 166–169.

- ↑ Dieter Pesch: The Martins Customs in the Rhineland. Change and present position. (Dissertation) Münster 1969, p. 58.

- ^ Manfred Becker-Huberti : Celebrations - Festivals - Seasons. Living customs all year round. Special edition, Herder Verlag, Freiburg (Breisgau) 2001, ISBN 3-451-27702-6 , p. 37.

- ↑ Citizens and Tourist Association Essen-Frintrop 1922 e. V.

- ↑ Martinisingen. In: fulkum.de

- ↑ Martin Happ: Old and new pictures of the holy Martin. Customs and uses since the 19th century. Köln-Weimar-Berlin 2006, pp. 349–357, quotation p. 352.