Habsburg (castle)

| Habsburg | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Southwestern side of the Habsburg |

||

| Alternative name (s): | Habsburg Castle | |

| Creation time : | Around 1020/30 to around 1300 | |

| Castle type : | Höhenburg, summit location | |

| Conservation status: | West part preserved, east part decayed | |

| Place: | Habsburg | |

| Geographical location | 47 ° 27 '45.9 " N , 8 ° 10' 51.7" E | |

| Height: | 505 m | |

|

|

||

The Habsburg , in recent times also called Habsburg Castle , is a summit castle in Switzerland . It is located in the municipality of Habsburg in the canton of Aargau at an altitude of 505 m above sea level. M. on the elongated ridge of the Wülpelsberg. It is known as the ancestral seat of the ruling dynasty of the Habsburgs , whose rise began with the acquisition of areas in the vicinity. Radbot is said to have been the founder of the Habsburgs around 1020/30 . In 1108 Otto II was the first of the family to be documented as Count von Habsburg.

The Habsburgs only lived here for around two hundred years. The increasingly powerful dynasty of counts left the castle around 1220/30 because it appeared too small and not representative enough. It was then awarded to various servants . With the conquest of Aargau in 1415 by the Confederates , the Habsburgs, who had meanwhile established a far more important center of power in Vienna , finally lost their ancestral castle. The Habsburgs have been owned by the Canton of Aargau since 1804.

The first buildings were built in the early 11th century. The Habsburg was expanded into a double castle in several steps. At the beginning of the 13th century it reached its greatest extent. After the Habsburgs moved out, the older, front part of the castle in the east fell into ruin . The younger, rear part of the castle in the west remained and was able to preserve its appearance to this day, apart from a few renovations. Extensive archaeological investigations took place in 1978/83 and 1994/95 . The Habsburg has been a cantonal monument since 1948 and is one of the cultural assets of national importance in the Swiss inventory of cultural assets . The Palas is used as a restaurant since 1979, this is affiliated with a museum on the castle's history.

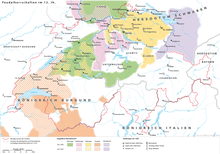

location

The Habsburg is located immediately northwest of the village center of the municipality of the same name , about 35 meters above the village at 505 m above sea level. M. The approximately three kilometers southwest of the old town of the district main town Brugg situated castle extends over a length of just over 100 meters on the rocky summit ridge of Wülpelsbergs. This limestone hill, covered by mixed forest, forms an extension of the Jura folds . Towards the west and north it drops steeply to the plain of the Aare valley , which is 160 meters below . The east and south sides of the ridge, on the other hand, form the edge of a gently sloping plateau that merges seamlessly into the Birrfeld . The A3 motorway runs through the Habsburg tunnel a little more than 400 meters southwest of the castle .

history

prehistory

During the Hallstatt period (1st and 2nd centuries BC) there was a small settlement at the site of today's castle. From the second half of the 1st century AD there was a signal station for the Romans on the Wülpelsberg . It was maintained by legionaries from the Vindonissa military camp four kilometers to the northeast (in today's municipality of Windisch ). The signal station enabled a line of sight between the camp and the Bözbergpass and was probably in operation even after the camp was closed in 101. At the end of the 3rd century, the Wülpelsberg served as a place of refuge for civilians. It was easy to defend and promised protection from the sporadic raids of the Alemanni , which the few soldiers in late Roman times could not offer.

Founding saga

According to a legend that Ernst Ludwig Rochholz first recorded in the middle of the 19th century, Radbot is said to have been the builder of the castle. He lived in Altenburg an der Aare , within the walls of a fort built by the Romans. In search of a hawk that he had lost during the hunt, his hunting party climbed the densely forested Wülpelsberg and found the escaped bird on top of the hill. Radbot recognized the favorable position of the hill and decided to build the "Habichtsburg" at this point.

Tschudi speaks out against the legend about the hawk. He writes about it: “But that a fable writer writes the Vesti has received the name Habichsburg from a Habich / contradicts the mock bishop Wernher's founder of the castle, sealed his own document / so he after Anno Domini 1027. gives Muri to Gottshuss and is still found unscathed / in it first Habesburg itself and not Habichsburg nempt. “It therefore derives the name Habsburg from Habesburg, in the sense of have / the property (to preserve or secure).

Since he had too little money to build the castle, Radbot asked his brother, Bishop Werner von Strassburg , for support. Werner granted this and came to visit to inspect the building. However, on the Wülpelsberg he only found a simple tower. Werner reprimanded Radbot sharply, whereupon the latter assured him that within one night the castle would have a strong wall. When Werner woke up the next morning, many knights and their servants were camped around the castle. Count Radbot reassured the startled bishop and said these knights had followed his call. Strong castle walls are only useful if they are defended by loyal and well-paid followers.

Ancestral seat of the Habsburgs

The origin of the ruling dynasty later known as "von Habsburg " is unclear. According to the Acta Murensia , created around 1160, Guntram der Reiche , who presumably descended from a branch of the Alsatian Etichones , is the progenitor. In the second half of the 10th century he had free float in Aargau , Breisgau , Frickgau , Upper Alsace and Zurichgau . In Aargau, the private property ( allod ) concentrated on the area between the Aare and the mouth of the Reuss , the so-called Eigenamt . Other possessions were further south in the area around Muri and Bremgarten . Guntram's son Lanzelin (or Kanzelin) gave the order to build a small castle, the Altenburg castle , using the existing walls of a Roman fort on the Aare . From here he managed the property on his own, where he had a particularly large number of lordly rights.

In a will dated 1027, Bishop Werner von Strassburg , son of Landolt - who is identified with Lanzelin, son of Guntram - is named the founder of the Habsburgs. However, this will turned out to be a forgery made around 1085. It is now certain that Werner's younger brother Radbot had the Habsburg built around 1020/30 around two kilometers south of Altenburg. The impetus for this is likely to have been a feud with his next younger brother Rudolf, which flared up over the property in Muri and led to the destruction of the manor house there. The foundation of the Muri monastery by Radbot and his wife Ita von Lothringen , daughter of Duke Friedrich von Ober- Lothringen , in the year 1027 - probably to atone for a debt they had taken on themselves - is also related to this.

The name of the castle is probably derived from the Old High German word hab or haw , which means "river crossing". This means a ford near Altenburg, where the boats going downstream had to dock in order to bypass the rapids that followed. The boat traffic could be monitored from the castle. The purpose of the castle was primarily to expand the country and to symbolize the claim to power. The prevailing thesis in the first half of the 19th century that the Habsburgs were built as a military base during the conflict with the Kingdom of Burgundy to secure the border and traffic routes has been refuted. In a document from 1108 referred to as Havichsberch , the name changed to Habsburg via Havekhesperch (1150), Habisburch (1213) and Habsburc (1238/39). Also in 1108, Otto II., The first member of the family as Count von Habsburg ( comes de Hauichsburch ) can be documented.

Although the Habsburgs had become landgraves in Upper Alsace and bailiffs of the Strasbourg bishopric at the end of the 11th century , in what is now Switzerland they were initially overshadowed by more powerful noble families. Thanks to their status as loyal followers of the Hohenstaufen dynasty and the creation of diverse family relationships, after the Lenzburger died out in 1173, they succeeded in taking over their county rights in western Zürichgau and Frickgau, and around 1200 also those in southern Aargau.

When more areas were added after the Zähringer died out in 1218, the Habsburgs soon proved to be too small and not representative for the counts who had become powerful. Between 1220 and 1230 they moved out of their ancestral castle and settled in the neighboring town of Brugg . In the decades that followed, a building later known as the “Effingerhof” (demolished in 1864 when a printing works was built) served as one of their most important residences there. In 1273 Rudolf I was elected German king and was also able to take over the inheritance of the Counts of Kyburg . Five years later he succeeded in defeating the Bohemian King Ottokar II in the battle of the Marchfeld and conquering the duchies of Austria and Styria . As a result, the center of power of the Habsburgs shifted to Vienna ; the scattered possessions in Switzerland, Alsace and southern Germany became the foreland .

- See also: List of the Habsburgs' tribe , to the Counts of Habsburg - the Habsburgs kept the title Count , then Prince Count of Habsburg until 1918

Changing owners

After the castle had served its purpose as the residence of the Counts of Habsburg, it was given to various ministerial families. The front part, which from then on remained uninhabited, went to the Lords of Wülpelsberg. The fiefdom above the rear part fell to the Habsburg taverns and the Habsburg-Wildegg truchess, who had always held important court offices at the Habsburg and also administered other castles in the vicinity ( Schenkenberg and Wildegg , the former probably also Freudenau ). They were originally a single family, but were divided into two lines by the second quarter of the 13th century at the latest.

The lords of Wülpelsberg died out around 1300 and the front part fell to the knight Werner II von Wohlen, who lived in Brugg. His son Cunrat III. Acquired part of the rear castle fiefdom from the stewardesses in 1364. Henmann von Wohlen, Cunrat's son, bought the remaining shares in 1371 and united the entire castle loan in one hand. In the early 15th century, the forest south and east of the castle was cleared and the hamlet of Habsburg was created, which initially consisted of only a few houses and only grew into a village in the 18th century.

Latent tensions between the German King Sigmund and the Austrian Duke Friedrich IV erupted in March 1415 at the Council of Constance , when Friedrich gave the antipope Johannes XXIII. helped to escape. Sigmund urged the Confederates to conquer Habsburg territories in the name of the empire, whereupon Bern quickly took the western part of Aargau. In view of the hopeless situation, Henmann von Wohlen capitulated without a fight at the end of April 1415 and recognized the new sovereigns from Bern. In return, he received a guarantee on his property. The Habsburgs, however, lost their ancestral castle for good.

Henmann von Wohlen transferred his property to his nephew Petermann von Greifensee in 1420, who sold the castle to the city of Bern in 1457. 1462 Habsburg got to Hans Arnold Segesser and finally in 1469 to the monastery Königsfelden in Windisch , once occupied by the Habsburgs to commemorate the murder of Albrecht I. had been established. When the monastery was closed in 1528 as a result of the Reformation , the Habsburgs came back into the possession of the city of Bern. The administration was now taken over by the Königsfelder Hofmeister, who stationed a high guard in the castle and sent an estate manager to cultivate the surrounding fields, forests and vineyards. Since 1804 the Habsburgs have been owned by the Canton of Aargau , which continued to use them as an estate .

Building history

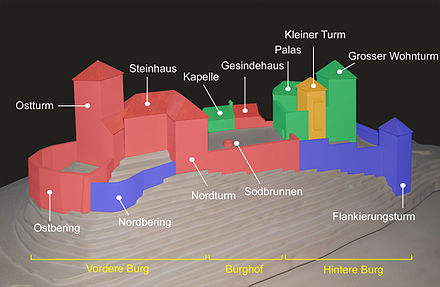

Palas, Small tower and Large residential towers are still there today.

The Habsburg was built in several construction stages. Its division into the front castle in the east, the central courtyard and the rear castle in the west goes back to the expansion of the foundations in the 11th century.

The oldest part, the front castle, which had fallen into ruin, initially consisted mostly of wood . Subsequent building activity destroyed remains and traces. The stone house is dated to the second quarter and the middle of the 11th century. Servant and farm buildings were in the courtyard and are likely to have been made of wood. A curtain wall , built as a dry stone wall or as a wooden palisade , surrounded the stone house on three sides.

In the last third of the 12th century, the front part of the castle was significantly expanded. Here, the stone house by East Tower, Ostbering was Torzwinger and North Tower added, while in the courtyard chapel and a Sodbrunnen emerged. The walling of the courtyard and the construction of the small tower, the first part of the rear castle, also fell during this period. The construction activity in the 12th century was limited to the north ring, which connected the north tower with the east ring. The front castle was largely completed.

At the beginning of the 13th century, work on the rear castle began. On the west side of the small tower was the particularly strong fortified large tower, on the north side another wall with the flanking tower in the extreme west. At the turn of the 13th to the 14th century, the Palas, protruding to the south, followed . Since the front castle had already been left to decay at that time, a section ditch was dug in the castle courtyard to better defend the rear castle and two more walls were built. The remaining remains of the front castle were razed around 1680 and the site leveled in 1815 . The rear castle was renovated in 1866/67, 1897/98, 1947/49, 1979 and most recently in 1994/96.

Todays use

The hall has been used as a restaurant since 1979. Tables are located in the knight's hall on the second floor, in the castle parlor to the southwest and in the Gothic hall to the southeast on the first floor and in the tavern on the ground floor. The Jägerstube in the small tower and the castle courtyard are also used by the local restaurants. The managed premises are designed for around 200 people. A wine cellar is attached to the restaurant.

In the small and large towers there is a free exhibition with display boards about the Habsburg dynasty, the history of building and settlement and everyday life in the castle in the Middle Ages. The castle has been part of the Museum Aargau network since 2009 .

Front castle

| Construction stages | |

|

2nd quarter and middle 11th century. Last third 11th century 12th century |

Early 13th century 2nd half of 13th century 13th / 14th century Century and 1559 |

| Legend | |

| A: Castle moat B: East Bering C: East tower D: Latrine E: North wall F: Zwinger G: Stone house (core structure) H: North tower | J: Gate K: Nikolaus Chapel L: Section ditch M: Inner courtyard N: Small tower O: Palas P: Large tower Q: Flanking tower |

Stone house

The stone house contains the oldest remaining structural remains of the entire complex. The building, which dates from the founding time around 1020/30, was initially free-standing. The side length was 18.5 by 13.2 meters, with which the stone house far exceeded the dimensions of contemporary castles in the wider area. The wall thickness of 1.9 meters suggests that the multi-storey stone house served not only for representation but also for defense purposes.

The walls have only been preserved up to a height of almost two meters. They consist of small house stones and have interrupting gaps in places. On the east side there is a door opening leading into the basement-like ground floor. The entrance on the north side was built in later, as is evident from the remains of the reveals . Inside there is a transverse wall that was built in the last third of the 11th century and in the 12th century was provided with a wall on both sides. This measure suggests an increase in the stone house. The function of two stumps of the wall attached to the north wall at that time remains unclear. The part west of the transverse wall is occupied by a water reservoir built in 1908 .

East Tower and East Bering

Immediately to the east of the stone house was a moth , an artificially created mound of earth that sloped steeply towards the neck ditch . On this hill stood the rectangular east tower with a side length of 9.5 by 9.2 meters. It is unusual that the east tower, built in the last third of the 11th century, was rotated by about 45 ° compared to the stone house, so that it only touched the older core building with one corner. On the north side of the tower there was a small square of walls that served as a latrine shaft . The Ostbering was built at the same time as the east tower. This circular wall began at the latrine shaft, then led along the edge of the neck ditch and finally ended on the south side at the gate kennel . The also artificially created neck ditch is now easily recognizable as a prominent incision in the ridge.

North Tower and North Bering

The north tower was added to the north-west corner of the stone house. Its base was 8.5 by 8.2 meters, the wall thickness 1.3 meters. Its exposed location on the steeply sloping northern slope of the ridge led to a poor state of preservation of the tower walls and to landslides of the debris filling, which leveled the terrain. A ground-level hearth made of tamped clay indicates that the north tower served as a kitchen building. In the northeast corner there was a small cellar measuring 2.2 by 1.8 meters. This could only be entered from above through an opening in the ceiling.

The north bering was not built until the 12th century and closed the gap in the wall that had existed between the north tower and the east ring. Its winding course is probably due to the fact that a weakly walled section collapsed and was rebuilt somewhat offset.

Gate kennel and gatehouse

The south bering was in front of the south flank of the stone house and the east tower by around five meters and formed a 22.5 meter long gate fence with outer walls 1.3 meters thick. At the eastern end, where the wall met the east ring and the east tower, was the front castle gate. After passing the Zwinger, you entered the courtyard through the actual castle gate. This second gate was initially just a simple passage, but was expanded into a gatehouse around 1200. The gatehouse protruding into the castle courtyard, of which only remains of the foundations remain, was the western end of the gate kennel; its eastern wall was in line with the western wall of the stone house.

Courtyard

The central courtyard was an average of 32 meters long and 30 meters wide. It formed a largely flat surface between the front and rear castle. At its edge were a section of ditch , the castle chapel , the servants' quarters , a Sodbrunnen and a cistern . During the 17th and 18th centuries, the courtyard was the site of a lime kiln and two swamp lime pits . The lime burning site was undoubtedly built from demolition material from the front castle.

Section trench

When the section trench was dug in the 14th century, the front part of the castle was already in such a bad structural condition that it could no longer fulfill its defensive function. The owners at that time, the Lords of Wülpelsberg, were primarily interested in the fiefdom and let the building fall into disrepair. Therefore the Truchsesse von Habsburg-Wildegg decided to better protect their own part of the castle. They had a ditch dug, which served as an approach barrier to protect the east side of the rear castle. The trench had an average width of 7.4 meters and a depth of 2.5 to 3.7 meters. After an almost dam-like castle path had been laid in it in 1562, the moat was filled in around 1650/70.

Building and fountain

The servants' house was at the point where the section trench had been subsequently dug. It was probably 10 meters long and 7.5 meters wide and had a small annex on the west wall that served as a latrine shaft. The castle chapel is one of the few buildings that have not yet been excavated. On the basis of old illustrations, including a watercolor by Hans Ulrich Fisch from 1634, some statements can still be made about the building, which was demolished in 1680. It should have been built on to the east of the servants' house and had two storeys.

The top of the well had an oval mouth 2.9 meters wide and 2.4 meters long. When it was accidentally rediscovered by an excavator driver, it was completely filled with limestone fragments and gypsum stone. Presumably it is the excavation of a gypsum pit in Habsburg or Windisch, which was filled in in the 19th century. On the occasion of the conservation in 1995, drillings resulted in a depth of 68.5 meters. The cistern, which was built at the beginning of the 13th century, was located at the gatehouse somewhat exposed outside the curtain wall, whereby the scoop shaft should have led up to the top of the curtain wall.

Rear castle

The rear castle has largely been preserved, albeit with numerous structural changes. In 1983, Aargau Cantonal Archeology carried out a comprehensive building survey. She found that the previous dating was incorrect for all buildings, and came to a very different result, especially for the small tower. So it was previously assumed that the large tower was built around 1020, now its construction time is estimated at the beginning of the 13th century. The small tower, however, had to be from 15./16. Century can be predated to the last third of the 11th century. The construction time of the Palas will be the 12./13. Century re-estimated to the middle of the 13th century.

Small tower

The small tower was built during the expansion at the end of the 11th century and has a footprint of 7.6 by 7 meters. It was part of a previous building of today's rear castle, which was replaced in the early 13th century by a hall and a large tower. During this renovation, the small tower was preserved. When the inner courtyard was converted into a residential wing at the end of the 16th century, the height of the small tower was reduced. In 1937/38 and 1947/49, extensive redesigns (modern interior fittings, installation of new intermediate floors and windows) resulted in the loss of other old buildings.

Only two walled-up window notches on the original first floor with an inwardly and outwardly sloping reveal can be ascribed to the original structure without a doubt. The portal walls of the walled-up high entrance are made of sandstone and probably originated from a renovation in the 13th century, as this type of construction only appeared at this time. On the north facade there are the beginnings of a toilet dungeon. The two high-lying narrow notches with an inwardly sloping soffit come from a later medieval construction phase. The other window and door openings date from the 16th to 20th centuries.

Big tower

The big tower was built at the beginning of the 13th century. It is 20.15 meters high and has a diamond-shaped floor plan of 10.2 by 10 meters. At the base, the wall thickness is 2.1 meters, which is reduced to 1.8 meters at a height of 10.5 meters through an internal recess. The tower was used for living and consists of megalithic masonry, the typical masonry for castles in this area. The roughly hewn quarry stones are built in layers on top of each other.

The original entrance is 7.4 meters above the courtyard floor, the entrance on the ground floor was only excavated in 1898. The four present-day intermediate floors were all built after 1866 and are no longer at their original altitude. With one exception, they cannot be precisely dated. The lowest intermediate floor was pulled in below the old entrance in 1995 and is only accessible from above. It has no medieval predecessor and serves as weather protection for the castle museum.

Today's second mezzanine floor was originally the first floor from where the tower could be entered. The remains of the chimney can also be found here in the northwest corner , which was probably seldom or never used, as no traces of soot were found during the construction inspection in 1995/96. Today's third floor was originally the second. There the tower can be exited through a door in the east wall. Today, due to the raised floor, the passage has a staircase leading down to the portico in the inner courtyard.

In front of the building of the palace there was a circumferential, two-storey arbor at this height on the outside of the tower, which could also be entered this way. In any case, the walled-up beam holes found there allow this statement. The upper storey of the arbor was probably also accessible from the third storey at the time. Today's fourth floor must have been covered by a square pointed helmet in the Middle Ages . The roofing in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period can only be proven on the basis of contemporary image documents, as the tower was given a new upper end with a crenellated crown in 1866. When the top wall sections were redesigned, any roof supports that were still there were destroyed and can therefore no longer be verified.

Hall

The rectangular palace closes to the south prominent, east to the big tower on. The walls are dated to the middle of the 13th century, so they are younger than those of the great tower. The hall has three floors and has a basement. On the west wall are the remains of a toilet dungeon. The building was extensively rebuilt in 1559 and basically got its current appearance. The windows facing east and south (two and three-part Gothic window groups) as well as the gable roof with east-facing Gerschild come from this period. Access to the individual floors of the palace is via the staircase and arbor system in the inner courtyard, which was renovated in 1948. Two late Gothic decorated oak pillars with saddle wood support the cellar ceiling. The flat barrel ceiling above the guest room on the ground floor also dates from 1948 , a copy of the original from 1559.

The castle room is on the first floor. This room largely corresponds to the original from 1559. It has a flat barrel ceiling, the beams of which are decorated with star, spiral and spiral wheel motifs; the runners are heart-shaped. Ribbed oak pillars serve as corner supports, and the donkey's back of the entrance portal is profiled in the same way . In one of the corners there is a tiled stove from the 18th century, which was previously in the rectory of Würenlos . The white cornice, plinth and tile tiles are painted with idyllic castle landscapes and floral decorations. It is believed that it is a work from Muri . In the room adjoining the castle room there is a simple box oven that was installed in 1948. He has picture tiles with ruined landscapes in rocaille frames. The furnace is signed by Johann Jakob Fischer from Aarau with the year 1744.

The knight's hall on the second floor was originally divided into several chambers and was given its present form in 1913/14. Inside there is a prism-shaped oven with green glazed relief tiles. These tiles from the 17th century are attributed to the Steckborn workshops (previously in Ermatingen ), but this assumption cannot be confirmed by written sources or signatures. Motifs of the stove are female allegories of virtue standing under arches and between pilasters , while putti cavort between lions' heads and scrollwork in the base frieze .

Inner courtyard and flanking tower

The inner courtyard in the form of an irregular "U" connects the small tower, large tower and hall. It was roofed over in 1594 and converted into a residential wing. The originally slightly inclined monopitch roof was prone to storm damage and was therefore replaced by a more inclined one in 1634. As a result of dilapidation, this building had to be removed again at the beginning of the 19th century, which is why the inner courtyard is now exposed again. On its east side it is bounded by the courtyard wall (previously also by the section ditch).

The flanking tower that was connected to the courtyard wall has not been preserved . It is attributed to the construction phase at the beginning of the 13th century and protected the north-western flank of the castle complex. A branch of the wall leading from the tower may have sealed off the ridge to the west.

Excavation finds

Excavations 1978 to 1983

In the area of the front castle, under the viewing platform, a water reservoir was built in 1908. Scientifically supported excavations did not take place until seventy years later, when the reservoir had to be expanded due to the population growth of the village of Habsburg. The Aargau Cantonal Archeology took this project as an opportunity to excavate the now hidden ruins and make them accessible to the public in a preserved form. The excavations took place between 1978 and 1983 in four stages. An exploratory excavation in the late autumn of 1978 served to precisely localize the ruins and to determine the ideal location for the new water chamber. In the late summer of 1979 a three-month excavation campaign led to the discovery of various wall sections in the western part of the front castle. Some of these had to give way to the reservoir and were later reconstructed on its cover. The investigation and restoration of the central section followed in 1980, and finally that of the eastern section in 1983.

The Roman finds are mostly building ceramics such as bricks or bricks. Particularly noteworthy are fragments of tile bricks with brick stamps from the 21st Legion ( Legio XXI Rapax ), which was stationed in Vindonissa from 44 to 69 AD. A coin from the time of Emperor Probus (276–282) was also found. The historian Franz Ludwig von Haller reported in 1811 that he had found a silver coin from Emperor Hadrian (117-138) on the Habsburg . Numerous spoils are built into the east tower . These come from the ruins of Vindonissa and were brought to the Wülpelsberg in the Middle Ages.

Animal bones make up the main part of the medieval finds and come mainly from the latrine shaft and the core structure of the east tower. This also includes semi-finished products and waste of bone and horn carvings from the 11th and 12th centuries. The second most frequently found fragments of ceramic objects, mainly sparsely decorated pot shards from the period from 1020/30 to around 1100, were found by the archaeologists funnel-shaped to the lip-shaped edge. In the early 13th century, there was finally the transition to groin edges.

Various finds testify to an upscale lifestyle of the castle residents. In addition to an aquamanile in the shape of a bull and shards of an imported amphora from Pingsdorf ceramics , traditional costume components made of non-ferrous metal, glass finger rings and a board game figure made of blue glass should be mentioned. Since only a few stove ceramics came to light, it can be concluded that the tiled stoves will be demolished according to plan when leaving the front castle and using them elsewhere. Iron found objects are mainly belt buckles and agricultural and commercial implements. In addition, two coins were found, one of which turned out to be the issue of the Fraumünster in Zurich (approx. 1055 to 1100).

From the findings it can be concluded that the housekeeping and everyday way of life of the early Habsburgs hardly differed from that of their subjects. The social primacy was expressed especially in the large consumption of meat as well as the possession of glass objects, valuable clothes and cash.

Excavations 1994/95

Planned underground extensions for the restaurant triggered further excavations in the castle courtyard in 1994. In terms of quantity, these lagged behind the excavations from 1978 to 1983. In addition, the high medieval find layer in the castle courtyard was severely impaired by modern disturbances such as factory management.

Numerous ceramic parts and a few animal bones from the earlier Iron Age were found in a culture layer in the castle courtyard . This cultural layer is attributed to the Hallstatt period of level C / D (6th and 7th centuries BC). In this layer the blade of a stone ax came to light, which suggests that people were already on the Wülpelsberg during the Neolithic Age . Since it is a single find, settlement during this period should be excluded. It is also possible that the blade only got there later.

In the medieval cultural layer, there were isolated Roman objects (brick fragments and a spoil made of shell limestone ), so that one can assume that objects found secondarily were relocated. Underneath were some pot shards and a horseshoe from the 11th / 12th. Century. Green glazed tile fragments from the late 14th century are worth mentioning, which come from an oven that was probably demolished when the palace was rebuilt in 1559. The fragment of an iron helmet is about the same age. A silver coin was also found, a minting of the Archbishops of Salzburg at the time of Frederick IV (1441–1452) or Sigismund I (1452–1461). The backfilled section of the trench contained plenty of finds from the 16th and 17th centuries, including many green glazed ceramic vessels, but also tallow lamps, leaf tiles and fragments of glass bottles and beakers. Metal found objects were mostly of an agricultural nature, such as spades, sickles and horseshoes. There were also door hinges and components of traditional costumes. These objects are likely to be the legacy of wealthy farmers or petty bourgeoisie who managed the estate on the Habsburg.

Archaeozoological evaluation

Around 120 kg of bones came from the excavations in 1978/83 and 1994/95, of which only a small part was archaeozoologically evaluated. From the 11th to 13th centuries, canton archeology mainly evaluated bone finds from the undisturbed excavation layers in the east tower of the front castle. From the early modern era (16th century) the bones from the trench were evaluated. In all four layers examined, bones from domestic animals predominate, while wild animals make up only a small proportion. The hunting so had no economic significance. A relatively high proportion of bird of prey bones was found in the topmost excavation layer of the east tower. It should be noted here, however, that at least the kestrels could have got into the layer for natural reasons and not as municipal waste, since this layer was created when it was uninhabited.

Ratio of the main species, according to the number of bone fragments:

| Excavation layer | Domestic cattle | pig | Goats , sheep | Wildlife | Total number (including indefinite) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bottom layer, east tower | 166 | 406 | 158 | 40 | 953 |

| Middle layer, east tower | 31 | 128 | 46 | 28 | 264 |

| Top layer, east tower | 178 | 931 | 132 | 151 | 1784 |

| Section ditch, castle courtyard | 247 | 222 | 35 | 16 | 718 |

The bone finds show that there was a shift in meat suppliers. In the Middle Ages, pigs, which were often slaughtered before sexual maturity, dominated, while domestic cattle were increasingly consumed in the early modern era. The majority of domestic cattle were slaughtered as adult animals. It is interesting that the chicken does not have more than a percent by weight of bones in any of the layers and can therefore be classified as meaningless as a meat supplier.

literature

- Stephan M. Leuthard, Heirich Gabriel: Palaces and castles of Aargau , Editions Ovaphil, Lausanne 1976.

- Werner Meyer: Castles of Switzerland. 8th volume, Silva-Verlag, Zurich 1981-1983, pp. 70-72.

- Peter Frey: The Habsburg in Aargau. Report on the excavations from 1978–1983. In: Argovia. Annual publication of the Historical Society of the Canton of Aargau, Volume 98. Sauerländer Verlag , Aarau 1986, ISBN 3-7941-2834-6 .

- Peter Frey. The Habsburg. Report on the excavations of 1994/95 . In: Argovia, annual journal of the Historical Society of the Canton of Aargau, Volume 109. Verlag Sauerländer, Aarau 1997, ISBN 3-7941-4469-4 .

- Marcel Veszeli, Jörg Schibler: Archaeozoological evaluation of bone finds from the Habsburg. In: Argovia, annual journal of the Historical Society of the Canton of Aargau, Volume 109. Verlag Sauerländer, Aarau 1997.

- Bruno Meier : A royal family from Switzerland. The Habsburgs, Aargau and the Confederation in the Middle Ages. Verlag hier + now, Baden 2008, ISBN 978-3-03919-069-0 .

- Peter Frey, Martin Hartmann, Emil Maurer : Die Habsburg (= Swiss Art Guide. Series 43, No. 425), 6th, revised edition. Edited by the Society for Swiss Art History. Bern 1999, ISBN 3-85782-425-5 .

- Peter Frey: Land of castles and small medieval towns. In: Limitless. Accompanying brochure for the anniversary exhibition. Brugg, no year.

Web links

- Dominik Sauerländer: Habsburg (castle). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Habsburg Castle - ancestral seat of a dynasty

- Habsburg Castle restaurant

- Aargau Museum

- Castle world: Habsburg

- Habsburg in the inventory of historical monuments of the canton Aargau

Individual evidence

- ↑ Topographic national map 1: 25,000, sheet 1070 Baden. Federal Office for Topography , Wabern near Bern 2008.

- ^ Martin Hartmann, Hans Weber: The Romans in Aargau (p. 172). Verlag Sauerländer, Aarau 1985. ISBN 3-7941-2539-8 .

- ↑ Frey, Argovia 98, p. 64

- ^ Ernst Ludwig Rochholz, Swiss sagas from Aargau, Aarau 1856

- ↑ Meier, pp. 11-12

- ^ Aegidius Tschudi: Chronicon Helveticum

- ↑ Meier, p. 14

- ↑ a b Frey, Argovia 98, p. 107 - the statement that Ita is Werner's sister is incorrect

- ^ Historical - Website of the community of Habsburg , Karl-Friedrich Krieger, Die Habsburger im Mittelalter. From Rudolf I to Friedrich III., Stuttgart - Berlin - Cologne, 1994, p. 14.

- ↑ Meier, p. 32

- ↑ Max Baumann, Andreas Steigmeier : Experience Brugg - Volume 1. Verlag hier + now, Baden 2005. ISBN 3-03919-007-5 (p. 36)

- ↑ Frey, Argovia 109, p. 166

- ↑ a b c Frey, Argovia 109, p. 167

- ↑ Meier, pp. 166-167

- ↑ Frey, Argovia 109, p. 164

- ↑ a b Frey, Argovia 109, pp. 166-167

- ↑ a b Website of the restaurant business , accessed on March 29, 2009.

- ↑ Frey, Argovia 98, pp. 32-34

- ↑ Frey, Argovia 98, pp. 37-40

- ↑ Frey, Argovia 98, pp. 41-44

- ↑ Frey, Argovia 98, pp. 44-46

- ↑ Frey, Argovia 98, p. 47

- ↑ a b c Frey, Argovia 109, pp. 128-130

- ↑ Frey, Argovia 98, pp. 49-51

- ↑ Frey, Argovia 98, p. 52

- ↑ Frey, Argovia 98, pp. 54 ff.

- ↑ The outdated data comes from the book Die Kunstdenkmäler des Kantons Aargau, Volume II, Die Bezirke Lenzburg and Brugg from 1953.

- ↑ Frey, Argovia 98, pp. 57-58

- ↑ Frey, Argovia 109, p. 131

- ↑ Frey, Argovia 98, pp. 58-59

- ↑ a b Frey, Argovia 109, pp. 131-134

- ↑ a b Frey, Argovia 98, pp. 62-63

- ^ Statement from 1927 by the canton master builder H. v. Albertini

- ↑ Frey, Argovia 98, p. 59

- ↑ Frey, Argovia 98, pp. 24-28

- ↑ Frey, Argovia 98, pp. 63-64

- ↑ Frey, Argovia 98, pp. 64-67

- ↑ Frey, Argovia 98, pp. 68-69

- ↑ Frey, Argovia 98, p. 69

- ↑ Frey, Argovia 109, pp. 123-125

- ↑ a b Frey, Argovia 109, pp. 145-147

- ↑ a b Veszeli, Schibler, Argovia 109, pp. 177-179

- ↑ Veszeli, Schibler, Argovia 109, p. 183