megalith

As a megalith (from ancient Greek μέγας mégas "large" and λίθος líthos "stone") archeology describes a large, mostly uncut stone block that was erected and sometimes positioned in stone settings .

definition

In Northern and Western Europe, megalithic were originally large stone settings ( dolmen , from Breton taol 'table' and maen 'stone' , actually "stone table") and upright stones that either stand individually as menhir or are arranged in several, for example Form stone circles ( Cromlechs ).

In 1867, at the second Congrès International d'Anthropologie et d'Archéologie Préhistoriques , an agreement was reached on only designating monuments made of almost uncut stones as megaliths, for example not the Egyptian obelisks or the Parisian Halle aux blés . The walls of Tyrins have been called Cyclopean , not megalithic. However, this definition excludes, for example, the Triliths of Stonehenge and the megalithic temples of Malta , which are composed of worked stones. Colin Renfrew pointed out the difference in appearance and function between the older, uncut stone monuments and the newer, more complex constructions .

Following Glyn Daniel , only Neolithic buildings made of large stones are now referred to as megaliths, because otherwise, as Daniel remarks, some Welsh pigsties could also be described as megalithic.

Gordon Childe proposed in 1946 that additional structures should be included:

- Tombs made of smaller stones and with a cantilever vault roof , such as the cantilevered tombs in Attica and Antiparos ;

- Rock tombs , for example in Sicily , Etruria and the Iberian Peninsula ;

- collective stone boxes , like the stone boxes of Attica and Antiparos.

For Childe, only collective burials are to be classified as megalithic. Closed stone boxes for individual burials, on the other hand, are not locked, even if they are made of large stones, such as some dolmens in North Africa and Palestine .

- Stone circles can be part of a megalithic burial or exist independently of it.

- According to Childe, megaxyle architecture is to be distinguished from megaliths: "Timber architecture was translated into stone - in England, Etruria, India - and such translation need not imply a megalithic complex."

- Entrance stones with a soul hole ( porthole slabs ) are permissible signs of megalithic architecture. The Caucasian stone boxes, the Necropolis B of Tepe Sialk (Iran) and the large stone graves of India therefore also fall into this category.

Childe's definition is unwieldy and cannot be used in areas without bone preservation, and accordingly it has not caught on in further research.

In 1956, Karl Joseph Narr defined a megalithic structure as follows:

- Buildings made of upright unworked stones ( orthostats ) with a capstone placed on top of "a certain, not precisely defined size",

- Menhirs,

- Stone circles (Cromlechs),

- Rows of stones , which are missing in many areas.

Controversial types remain “large systems made from smaller stones” and “systems carved into the rock”. Fool adds that today there is "little inclination" to call domed tombs and tombs , as they are known from the Mycenaean Bronze Age, megalithic.

Typology

The first division of the megalithic structures in Northern Europe was made by Oskar Montelius . He distinguished dolmens, passage graves and stone boxes. His system was expanded by Sprockhoff and Schuldt, among others. There are now a large number of national and regional typologies that cannot be combined into a single linguistic usage. Therefore, Furholt et al. 2010 presented a classification that combines various individual features.

Cultural classification

The various megalithic structures in Europe and other continents do not necessarily suggest a common culture (" megalithic culture "). Pottery and other artefacts that accompany the stone setting do not always belong to the same culture; this also applies to the most common types, i.e. menhirs , dolmens , passage graves or stone boxes . According to others, the similarity of the megalithic structures preserved on the European Atlantic and North Sea coasts suggests a genetic relationship, even if the accompanying artifacts do not belong to the same culture, e.g. B. by colonization or cultural exchange .

Construction

In Europe, there are diverse relationships between the long-lived, often rebuilt megalithic and related sites made of less permanent material (such as wooden circles, etc.), within which one usually searches in vain for a scheme of dependencies, chronology and geographical distribution. This is usually only possible on a regional level. The question of whether the different regional types have independent origins or a common root is still open. Various construction methods are known in Europe in which (at least in part) megaliths were used:

- in Scandinavia and northern Central Europe : dolmen, gallery grave , passage grave , large dolmen , barn bed without chamber , barrow , stone box , polygonal barn and ancient barn ;

- in the British Isles : Boulder Burial , Cairn , Clava Cairn , Clyde tomb , Cotswold Severn tomb , Court tomb , Passage tomb , Portal tomb (burial mound with portal stones) and Wedge tomb ;

- in France : cairn, gallery grave, dolmen with side chambers ;

- in the Iberian Peninsula : Anta , Mámoa , Pedra Formosa ;

- on the islands of the western Mediterranean : Giant Tomb , Naveta , Talayot , Taula , Maltese temples , Torre ;

- mainly in Greece and West Anatolia mostly in the area of the Mycenaean culture : Tholos .

In Europe, individual megaliths (menhirs) or groups of individual stones have been set up in stone settings in some regions :

- Individual stones: menhir, baitylos , statue menhir ;

- Rows of stones ;

- Stone circles (Cromlechs): In south-east Scotland there are stone circles with recumbent stone circles .

Standing stones or similar megalithic forms from the Iron Age or the Early Middle Ages are not part of the traditional megalithic systems. This includes:

- Building blocks ,

- Gotland picture stones ,

- Rune stones in Scandinavia,

- Pictish symbol stones ,

- Ogham stones ,

- Mask stones ,

- Cross slabs and

- the Iron Age fluted menhirs of Brittany .

Partly also:

- Ship settlement mostly in Sweden,

- other Iron Age stone setting (circles, semicircles or avenues) mainly in France, England,

- Baityloi from Roman times as part of stone cults,

Origin of the building material

The stones of the northern European megaliths come from the deposits of the Ice Age (erratic blocks, granites , gneisses and other rocks). Many of the remaining megaliths were broken from relatively soft sedimentary rocks.

New research

The formation of theories as well as the criteria for inclusion or exclusion as a megalithic monument or building were limited until the end due to the limited possibilities for age determination: This means that an essential category was missing to determine affiliations or simultaneity and sequences via dating.

As late as 1956, Karl Joseph Narr had basically pointed out that “prehistoric megalithicism does not coincide with any group of forms that can be worked out by archaeological means, or that with some probability it can be shown to be rooted in such a complex.”

In 2015, the University of Gothenburg started a project under the direction of the Neolithic researcher Bettina Schulz Paulsson, which opened up a total of 35,000 existing megalithic objects on mainland Europe and in the western Mediterranean area, including those with older findings. With the now significantly improved analysis technology of the radiocarbon method, "the age of 2410 sites was (determined) on the basis of samples, some of which were already examined earlier, in the context of megalithic buildings and artifacts of the same age from neighboring cultures."

Schulz Paulsson summarized the work in book form in 2017; A year and a half later, the scientific journal PNAS ( Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America ) published its report and thus constituted it as basic research.

For the results of the research see: Data collection and conclusions

Occurrence

In Europe

The construction with megaliths ( French pierre dressée ) took place in Europe between around 4500 BC. BC ( Brittany ) and 800 BC When the last large stones were built in Sardinia . The menhirs are found primarily in southern and western Europe; in Germany between Saarland and Thuringia.

Many megalithic systems have been destroyed since industrialization. Megaliths fell victim to land consolidation, landscaping projects or the construction of churches and ports. In northern Germany, they were used to build dikes and, in shredded form, as paving stones.

- Numerous systems have been preserved in Great Britain and Ireland. There are around 1,600 megalithic tombs in Ireland.

- There are over 900 megalithic buildings in Germany in the three large coastal states as well as in North Rhine-Westphalia, Brandenburg and Saxony-Anhalt, and a few in southern Baden-Württemberg.

- 53 megalithic structures in the Netherlands have been preserved.

- In Belgium , the five megalithic complexes near Wéris are worth highlighting, three of which are still preserved today.

- Denmark still has over 2067 plants (from around 5000 before), more than a quarter of them in the former offices of Holbæk (317) and Sorø (245) in western Sjælland .

- There are still more than 450 systems in Sweden (from around 650 once).

- Larger megalithic complexes in Switzerland include the Menhir of Bonvillars , the Alignement of Clendy , the Parc la Mutta in Falera , the stone row of Lutry and the Chemin des Collines in Sion .

- The figures for megalithic sites in Poland are not reliable, but are included in the pre-war German figures .

- There are megaliths in southern Russia too.

- Numerous megaliths can be found in Portugal (especially near Évora ).

Outside of Europe

Megaliths can be found in Georgia , Turkey , Syria and Palestine , India , Indochina , Indonesia and Korea as well as in Africa ( North Africa , Ethiopia and Madagascar ) without a genetic link between the locations having to exist. A geological curiosity is the split Al-Naslaa megalith near the Tayma oasis in Saudi Arabia . The Moai statues of Easter Island , the Olmec heads , a few Toltec and Aztec statues and several monuments in Tiahuanaco can also be described as "megalithic".

interpretation

In many cases it is now unknown what purposes megalithic structures served and why they were built. They often served as graves and for religious purposes. Sometimes a function as a memorial, as a border marker or as a symbol of political power comes into consideration. Some objects are also considered to be of importance for astronomical calculations, a well-known example is the Stonehenge complex ; The observatory at Nabta-Playa in southern Egypt is less known .

The size of the stones enticed people used to on giant to believe (Giant), who have transported the stones had. This can still be seen in the etymology of the name " Hinkelstein ": Due to a misunderstanding, the "Hünenstein" became a "Hühnerstein". In the south-west of Germany there are the dialect words Hünkel or Hinkel for "chicken" - this is how the German word formation "Hinkelstein" came about. With Christianization, legends emerged about the creation of megaliths by the devil's hand. Some have the devil in their name ( Teufelssteine , Devil's Arrows , Devils Circles etc.).

In the 18th and 19th centuries there was again interest in the megalithic systems. At that time, many believed that the buildings could be traced back to the Druids of the Celts , such as the English antiquarian William Stukeley .

Non-Megalithic Traditions in Europe

Megalithic systems could only arise where stones could be worked with the resources of the time. In the area of the funnel beaker culture (TBK), these were essentially the erratic blocks of the Ice Age that only had to be transported or, if necessary, split. Where erratic blocks were not available in sufficient quantity and size, other structures were built, e.g. B. in the area of the southern TBK the death huts and the chamber facilities in the low mountain range (south of the Mittelland Canal ) in Germany, mainly between the Weser and Saale.

See also

literature

- Michael Balfour: Megalithic Mysteries. An Illustrated Guide to Europe's Ancient Sites. Dragon's World, Limpsfield 1992, ISBN 1-85028-163-7 .

- Hans-Jürgen Beier : The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest (= contributions to the prehistory and early history of Central Europe. Vol. 1, ZDB -ID 916540-x ). Beier & Beran, Wilkau-Hasslau 1991 (also: habilitation paper, University of Halle, 1991: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs in the five new East German federal states (formerly GDR) - an inventory ).

- Karl W. Beinhauer, Gabriel Cooney, Christian E. Guksch, Susan Kus (eds.): Studies on megalithics. State of research and ethnoarchaeological perspectives / The megalithic phenomenon. Recent research and ethnoarchaeological approaches (= contributions to the prehistory and early history of Central Europe. Vol. 21). Beier and Beran, Weissbach 1999, ISBN 3-930036-36-3 .

- Julian Cope: The Modern Antiquarian. The Pre-Millennial Odyssey through Megalithic Britain. Thorsons, London 1998, ISBN 0-7225-3599-6 (guide to megalithic sites in Great Britain).

- Julian Cope: The Megalithic European. The 21st Century Traveler in Prehistoric Europe. Element, London 2004, ISBN 0-00-713802-4 (travel guide to megalithic sites in “Rest of Europe”).

- German Archaeological Institute , Madrid Department: Problems of Megalithic Tomb Research . Lectures on the 100th birthday of Vera Leisner (= Madrid Research. Vol. 16). de Gruyter, Berlin and others 1990, ISBN 3-11-011966-8 .

- John D. Evans, Barry Cunliffe , Colin Renfrew (Eds.): Antiquity and Man. Essays in honor of David Glyn. Thames & Hudson, London 1981, ISBN 0-500-05040-6 .

- Mamoun Fansa : Great stone graves between Weser and Ems (= archaeological messages from northwest Germany. Supplement 33). Third, modified edition. Isensee, Oldenburg 2000, ISBN 3-89598-741-7 .

- Joachim von Freeden: Malta and the architecture of its megalithic temples. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1993, ISBN 3-534-11012-9 .

- Daniel Glyn: The megalith builders of Western Europe. Greenwood Press, Westport CT 1985, ISBN 0-313-24836-2 .

- Evert van Ginkel, Sake Jager, Wijnand van der Sanden : Hunebedden. Monuments van een Steentijdcultuur. Uitgeverij Uniepers, Abcoude 1999, ISBN 90-6825-333-6 (monograph on megalithic tombs in the Netherlands).

- Johannes Groht : Temple of the ancestors. Megalithic buildings in Northern Germany. AT-Verlag, Baden etc. 2005, ISBN 3-03800-226-7 .

- Roger Joussaume: Dolmens for the dead. Megalith building throughout the world. Batsford Books, London 1988, ISBN 0-7134-5369-9 .

- Raiko Krauß : The prehistoric megalithic tombs of Tunisia. In: Journal for Archeology of Non-European Cultures. Vol. 2, 2007, ISSN 1863-0979 , pp. 163-181.

- Raiko Krauss: How old are the North African megaliths? In: Hans-Jürgen Beier , Erich Claßen, Thomas Doppler, Britta Ramminger (eds.): Neolithic monuments and neolithic societies. Contributions from the meeting of the Neolithic Working Group during the annual meeting of the North-West German Association for Ancient Research in Schleswig, 9. – 10. October 2007 (= Varia neolithica. 6 = Contributions to the prehistory and early history of Central Europe. Vol. 56). Beier & Beran, Langenweißbach 2009, ISBN 978-3-941171-28-2 , pp. 153-159.

- Johannes Müller : On the absolute chronological dating of the European megaliths. In: Barbara Fritsch, Margot Maute, Irenäus Matuschik, Johannes Müller, Claus Wolf (eds.): Tradition and Innovation. Prehistoric archeology as a historical science. Festschrift Christian Strahm (= International Archeology. Studia honoraria. 3). Marie Leidorf, Rahden 1998, ISBN 3-89646-383-7 , pp. 63-105.

- Salvatore Piccolo: Ancient Stones. The Prehistoric Dolmens in Sicily. Brazen Head Publishing, Thornam 2013, ISBN 978-0-9565106-2-4 .

- Michael Schmidt: The old stones. Travel to the megalithic culture in Central Europe. Hinstorff, Rostock 1998, ISBN 3-356-00796-3 .

- Bettina Schulz Paulsson :: Time and Stone. The Emergence and Development of Megaliths and Megalithic Societies in Europe , Oxford Archaeopress Publishing Ltd., September 2017, ISBN 978-1-784916-85-5 .

- Andrew Sherratt : The genesis of megaliths: Monumentality, ethnicity and social complexity in Neolithic north ‐ west Europe. In: World Archeology. Vol. 22, No. 2, 2010, ISSN 0043-8243 , pp. 147-167, JSTOR 124873 .

- Ernst Sprockhoff : Atlas of the megalithic tombs. Parts 1-3. Rudolf Habelt, Bonn, 1966–1975.

- Ernst Sprockhoff: The Nordic megalithic culture (= manual of the prehistory of Germany. Vol. 3). de Gruyter, Berlin and others 1938.

- Sibylle von Reden: The Megalithic Cultures. Evidence of a lost original religion. Sixth edition. DuMont, Cologne 1989, ISBN 3-7701-1055-2 .

- Jürgen E. Walkowitz: The megalithic syndrome. European cult sites of the Stone Age (= contributions to the prehistory and early history of Central Europe. Vol. 36). Beier & Beran, Langenweißbach 2003, ISBN 3-930036-70-3 .

- Detert Zylmann : The riddle of the menhirs. Probst, Mainz-Kostheim 2003, ISBN 3-936326-07-X .

Web links

- Steinzeugen.de (private site)

- Menhirs on Eichfelder.de , website on mythology and archaic cults

- Stone circles - Menhirs - Dolmen - Ancient Stones (private site)

- Holtorf, Cornelius: Monumental Past: The Life-histories of Megalithic Monuments in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (English, as of 2009)

- Alain Gallay: Megaliths. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

swell

- ^ A b c V. Gordon Childe: The Distribution of Megalithic Cultures, and their Influence on Ancient and Modern Civilizations. In: Man. Volume 46, 1946, p. 97.

- ^ "[...] their function and indeed their appearance are quite different, so that the two groups should be discussed quite separately." Colin Renfrew: Before Civilization. The Radiocarbon Revolution and Prehistoric Europe. Penguin, London 1973, p. 134.

- ↑ Karl Joseph Narr: Archaeological notes on the question of the oldest grain cultivation and its relationship to high culture and megalithic. In: Paideuma. Communications on cultural studies. Volume 6, No. 4, 1956, ISSN 0078-7809 , pp. 244-250, here p. 246, JSTOR 40315506 .

- ↑ Martin Furholt, Doris Mischka, Knut Rassmann, Georg Schafferer 2010, MegaForm - A formalization system for the analysis of monumental building structures of the Neolithic in northern Central Europe. Jungstein Site November 25th, 2010, 2

- ↑ Martin Furholt, Doris Mischka, Knut Rassmann, Georg Schafferer 2010, MegaForm - A formalization system for the analysis of monumental building structures of the Neolithic in northern Central Europe. New Stone Site November 25th, 2010

- ^ V. Gordon Childe: The Distribution of Megalithic Cultures, and their Influence on Ancient and Modern Civilizations. In: Man Vol. 46, No. 4, 1946, p. 97, JSTOR 2793159 : “No single 'culture' as defined by types of pottery and other artifacts is represented by the furniture of these tombs in general, nor yet by that of the more widely distributed subclasses thereof - simple dolmens, passage graves (dolmens á galerie), and cists. "

- ↑ Mario Alinei : Origini delle lingue d'Europe. Volume 2: Continuità dal Mesolitico all'età del Ferro nelle principali aree etnolinguistiche. Il Mulino, Bologna 2000, pp. 468-482, especially pp. 477 f.

- ↑ La estatua-menhir del Pla de les Pruneres (Mollet del Vallès, Vallès Oriental)

- ^ Karl J. Narr: Archaeological notes on the question of the oldest grain cultivation and its relationship to high culture and megalithic. In: Paideuma. Communications on cultural studies. Volume 6/4 (1956), p. 249.

- ↑ Jan Osterkamp: Is there a common root of the megalithic culture? , February 11, 2019. Spectrum of Sciences . (Accessed March 8, 2020).

- ^ Bettina Schulz Paulsson: Time and Stone: The Emergence and Development of Megaliths and Megalithic Societies in Europe , Oxford Archaeopress Publishing Ltd., September 2017, ISBN 978-1-784916-85-5 .

- ↑ Ed .: James F. O'Connell, B. Schulz Paulsson: Radiocarbon dates and Bayesian modeling support maritime diffusion model for megaliths in Europe , Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America , Volume 116, No. 9 | Date = 2019-02-11 | Pages = 3460–3465 | DOI = 10.1073 / pnas.1813268116 | PMID = 30808740.

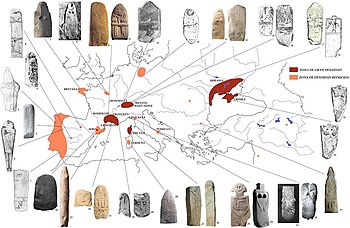

- ↑ photographs and drawings: 1y fourth-Bueno et al. 2005; 2.-Santonja y Santonja 1978; 3. Jorge 1999; 5. Portela y Jimenez 1996; 6. Romero 1981; 7.-Helgouach 1997; 8.- Tarrete 1997; 9, 10, 13, 14, 29, 30, 31, 32.-Philippon 2002; 11.-Corboud y Curdy 2009; 12. Muller 1997; 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 Arnal 1976; 24 and 25 August 1972; 26 y 27.- Grosjean 1966; 34. López et al. 2009 .

- ^ Carleton Jones: Temples of Stone. Exploring the megalithic tombs of Ireland. Collins Press, Doughcloyne 2007, ISBN 978-1-905172-05-4 , p. 10.