Passage grave

A passage grave is a large stone grave with a chamber and an access that is structurally separated from the chamber. Usually the ceiling of the corridor is lower than that of the chamber. Access to the chamber, often set off with a threshold stone, can be via a central, eccentric (p-dolmen, q-dolmen) or a side passage (cross-aisle passage grave).

Nomenclature and delimitation

The passage grave is called Jættestue ("giant room") in Denmark , Gånggrift in Sweden , Dolmen à couloir in France , and sepulcro de corredor in Spain. British-Irish systems have (translated) the same name ( Passage grave or Passage Tomb), but look (like the French systems) structurally completely different.

Dating

Passage graves were created by the Neolithic funnel cup culture . They can be found in Scandinavia , Northern Germany and the Netherlands . They were mostly erected here at the beginning of the MN A (Middle Neolithic A) between (3300-3000). In Prissé-la-Charrière in southwest France, the system was only used for a few generations, between 4400-4200 cal .

Typology

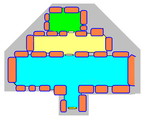

The access to the passage grave lies transversely to the longitudinal axis of the chamber. Square or round structures (in the upper picture on the right) are otherwise usually included in the dolmens. A different stipulation applies to passage graves in Sweden . There are some unusually small passage graves with only two cap stones in the area of distribution (e.g. Amelinghausen-Sottorf in the Lüneburg Heath , Klein Stavern in the Emsland ).

On the other hand, there are very long chambers up to 29 meters west of the Weser . East of the Weser, the Lehnstedt 82 and 83 (11.2 and 9.3 m) facilities in the Elbe-Weser triangle and the stone chamber at Dohnsen (16 m) are the exceptions in terms of chamber length. Although the bearing stones of passage graves (unlike Urdolmen ) are already upright on their smallest surface, some passage graves were built in pits ( stone chamber of Deinste in Lower Saxony). They are probably the earliest examples. The Trapgraf von Eext (staircase grave - D13 in Gieten Eext) - in the Dutch province of Drenthe is a specialty.

architecture

Floor plans of the chamber

The floor plans of the chambers, either oval, polygonal, rectangular or trapezoidal, also bulged (slightly D-shaped) or with parallel long and obtuse angled narrow sides, are almost always (not in the passage grave of Lovby Kirketomt ) significantly longer than wide. The megalithic complex of Ebendorf in Barleben near Wolmirstedt in Saxony-Anhalt is the only one with a shifted parallelogram as a floor plan. The large stone grave Bakenhus has a 23 meter long, boat-shaped chamber. Systems with axial access are considered dolmens in Germany .

- Floor plans

Access to dolmen and passage grave with quarters

According to Ewald Schuldt's terminology (cf. types of Mecklenburg megalithic tombs ), it differs from the dolmen in that it has a (lateral) access on one of the two long sides. The new German research sees it as a variant of the dolmen, which is regionally dominant in the province of Drenthe (Netherlands), in western Lower Saxony (as the Emsland Chamber ) and otherwise in Holstein , as the Holstein Chamber and in the bordering Mecklenburg , in eastern Lower Saxony and in Saxony -Anhalt and Scandinavia appear as a larger or smaller minority. Bornholm only knows about ten passage graves, no dolmens.

Chamber and passage

The width / length ratio of the passage graves is generally between 1: 1.2 and 1: 6. Only the long Emsland chambers clearly exceed this ratio with up to 1:14 ( De hoogen Steener in Werlte , approximately 30 m long). The usually short, but sometimes up to ten meters long dolmen access can open into the chamber in the middle or offset towards one end. Staggered corridors are particularly common in Holstein and led to the name Holstein Chamber. In the short corridor graves, the number of bearing stones (even or odd) on the access side is responsible for this. The Luneburg group of megalithic plants shows, according to Friedrich Laux quick transition from the Dolmentypen the passage grave. Over there:

- two ancient dolmen

- ten chamberless giant beds

- five enlarged or rectangular poles

- over 90 passage graves

Whether there was a succession of dolmens and passage graves, as postulated by early Danish research, has meanwhile become disputed. See construction crew theory .

Ceiling extension

While the passage grave initially only had ceiling structures that derive their statics from the load-bearing capacity of a three-point support (in the picture above), the final architectural step in the construction with boulders, the yoke construction. With it, three stones (a yoke ) are installed like a trilith as a static component in the overall concept. Because this two-point support is extremely unstable with unprocessed natural stones, the cap stones of the yokes support one another on the sides. The two ends of such rows of yokes, however, always consist of three-point supports, as only they give the entire construction the necessary support. A detail is the occasionally documented support of the cap stones on the intermediate masonry . Cover stones are next to gang stones, the stones removed first when chambers are destroyed.

Bezels

Passage graves are usually found in comparatively short, rectangular or oval barrows or in round hills due to their great length. In particular among Denmark's approximately 500 preserved passage graves, there is a considerable number that are located in round hills. Systems with double oval edging (Lähden, Thuine ) are known from the Emsland . Some passage graves on Lolland and Falster , which have long, narrow chambers and a short passage, are enclosed by giant or giant beds, which are otherwise typical of dolmens . In Lower Saxony, grave IV of the Oldendorfer Totenstatt, about 8 m long, lies in an 80 m long bed , and that of Drangstedt even in a 90 m long bed. A passage grave in Holstein lies in a barren bed over 70 m long. Even longer bezels are only known in Germany for other types of megalithic systems .

Local guys

The passage grave is a characteristic megalithic complex for the TBK, it was initially assigned its own time horizon. PV Glob does this in 1967. The passage burial period was between the dolmen and stone crate times . In Denmark about 500 of 2,800 preserved structures are passage graves.

Secondary chambers

30 Danish passage graves , especially common in Jutland , have side chambers ( Danish: Jættestue med bikammer ). 25 of these systems can be found in Jutland, especially by the Limfjord (e.g. Gadegård , Gamskær , Gundestrup 2 , Fjelsø , Lundehøj , Manstrup, Møllehøje from Kobberup , Mønstedt, Niels Jensens Høj, Nymark Brandalshøj, Ormehøj from Sævehalshøj , Stenshøj , Tustrup ), Vashøj / Storvad Høj and Thusbjerg , as well as 3 systems on Zealand (e.g. Drysagerdys near Dalby, Hørhøj and Kornerup Mark ), 2 on Lolland ( Bag-Hyldehøj , Torhøj ), and Rogenstrup on Falster .

The variously arranged secondary chambers were performed at the same time as the main chamber. That they had a special function can be deduced from the fact that quarters were built elsewhere at the same time , showing an even more differentiated division of the chamber. The majority of the secondary chambers are opposite the entrance. The Visi- or Hvisselhøj is unique in that the corridor opens up three parallel chambers, which are laid out in the manner of three shorter loaves of bread one behind the other.

Side chambers (not so-called front or side chambers ) are known mainly - and in far greater numbers (per system) from Brittany (French: Dolmen à cabinets latéraux or Dolmen transepté ) and from the British Isles (e.g. Loughcrew in Ireland, La Hougue Bie and La Varde on the Channel Islands , West Kennet Long Barrow and Stoney Littleton ) from Spain (e.g. Tholos from El Romeral ), but not from the rest of the northern district (Germany, Netherlands, Norway, Poland and Sweden ) the TBK.

Double-aisle grave

Some passage graves were built as double systems ( Danish Dobbelt- or Tvillingejættestue , Swedish called dubbelgånggrift ), in that two chambers usually have common bearing stones on their adjacent narrow sides.

Double-passage graves can be found in 57 examples on Zealand :

- Aldersro at Værslev, Børnehøj in Roskilde, Brailsdys, Djævelhøj of Tikøb, Drysagerdys at Dalby, Fårdrup, Fjellerup, Forsinge at Ubby, passage graves of Græse at Frederikssund, Gundsølille at Kirkerup, Hyldedysse at Rørby, Korshøj at Ubby, Lodden- or Nordenhøj at Rørby , Lodneshøj near Sneslev, Møllehøj in Hornsherred near Hyllinge Kirke, Ølshøj or Ullershøj near Blistrup, Olshøj (also "Onshøj von Kærby") near Rørby, Østrup near Undløse, Ormshøj near Årby, Månehøj- Måneshøj peninsula near Ørby, Selschausdal near Buerup, Slåenhøj near Kalundborg , Snogedysse near Gentofte (assumed in 1824), passage graves from Snæbum Tjørnehøj near Balby and the Troldhøj from Stenstrup.

- occasionally on Møn and Langeland ( in Tvedeskov ), Fyn , Ærø ( Lindsbjerg Dysse ) and Samsø (Rævebakken). At Röddinge on Mön , Klekkende Høj was apparently built from an over-long chamber, the axes of which lie on a line and do not form an angle, like the other structures in round hills. Double-aisle graves have parallel entrances.

- A dozen of these systems are known from North Jutland ( passage graves from Gundestrup , Snibhøj near Hobro , Ettrup , Iglsø near Skive and Langmosehøj south of the Tulsbjerge), especially from southern Himmerland .

- three 1956 L. Kaelas not yet known are in Skåne in Sweden ( Snarringe , Stenhögen and Stora Kungsdösen ).

In Aldersroe there are three passage graves in the same megalithic bed. In contrast to dolmens, several passage graves in a common enclosure are rare. B. also at grave no. 2 of the Kleinenknetener stones in Germany. Rarely, as at Græse , on Zealand, but more often in Jutland (passage graves from Snæbum), two chambers are separated from each other but related to each other, in the same hill.

The large stone grave Tannenhausen consisted of two large passage graves, the one adjacent at Tannenhausen, 4.3 kilometers north of Aurich in the Emsland , but their distance was about 5.0 m and they were in separate oval hills.

Germany

The Kleinenknetener stones are located near the small town of Kleinenkneten south of Wildeshausen in Lower Saxony. Hünenbett II is the only complex in which three passage graves (separated from each other) lie within a common enclosure, whereby the associated long mound has long been removed.

Holstein Chamber

The Holstein Chamber or North German Long Chamber is a rectangular shape of the passage grave that is predominantly represented in Holstein. With 58 plants (68%), this so-called southern group (south of the Eider ) is twice as strongly represented in Schleswig-Holstein as the approximately oval chamber of the northern group, with which it overlaps in the Eckernförde area. The length of the chambers varies between 3.0 and 8.5 m, with systems between 3.0 and 5.5 m making up about two thirds, while those over 6.0 m make up the remaining third. The width varies between 1.0 and 2.25 m. 60% of the chambers reach a width of 1.5 m. Usually the systems have three, but often four to six cap stones. Almost half of them were found to have a short corridor made of one or two pairs of stones. An eccentric position of the passage or the chamber opening to the chamber length occurs in 40% of the systems, while the middle position (20%) occurs mainly in long chambers. The rest is so disturbed that a statement about the location of the corridor cannot be made. The original shape of the hill can only be determined in 50% of the plants. According to this, the round hills predominate in the north, whereas the long beds in the eastern and western distribution area predominate, in each case by twice as much.

- to form

The klekkende høj , double passage grave at Røddinge on Mon.

Steenaben - trapezoid passage grave near Lamstedt

While the stone material mostly consists of the erratic blocks of the Ice Age ( boulders ), a few systems are made of other stone material ( Lübbensteine ). The “multicultural” grave field of Wartin offers another special form. Here a passage grave was created in a stone slab stone bed (E. Kirsch 1993), as there are no large debris on the terrace of the glacial valley of the Randow .

Passage grave box

Passage grave boxes are, according to Hans-Jürgen Beier, passage grave derivatives. They are much smaller than passage graves, possibly sunk, built from stone slabs and provided with lateral entrances. They are particularly common in the lower reaches of the Oder ( Beeskow , Klein-Rietz , both districts of Oder-Spree , Wartin 1 and 2 districts of Uckermark and Löwenbruch district of Teltow-Fläming , all in Brandenburg ). In Mierzyn (German: Möhringen) on the outskirts of Stettin there is another facility.

See also

literature

- German Archaeological Institute - Madrid Department: Problems of megalithic grave research. Lectures on the 100th birthday of Vera Leisner (= Madrid Research. 16). de Gruyter, Berlin et al. 1990, ISBN 3-11-011966-8 .

- Klaus Ebbesen: Danske jættestuer. Attika, Vordingborg 2009, ISBN 978-87-7528-737-6 .

- Mamoun Fansa : Great stone graves between Weser and Ems (= archaeological messages from northwest Germany. Supplement 33). 3rd revised edition. Isensee, Oldenburg 2000, ISBN 3-89598-741-7 .

- Peter Vilhelm Glob : prehistoric monuments of Denmark. Wachholtz, Neumünster 1968.

- Lili Kaelas: Dolmen and passage graves in Sweden. In: Offa . 15, 1956, pp. 5-24.

- Eberhard Kirsch : Finds from the Middle Neolithic in the state of Brandenburg (= research on archeology in the state of Brandenburg. 1). Brandenburg State Museum for Prehistory and Early History, Potsdam 1993, ISBN 3-910011-04-7 .

- Michael Schmidt: The old stones. Travel to the megalithic culture in Central Europe. Hinstorff, Rostock 1998, ISBN 3-356-00796-3 .

- Ewald Schuldt : The Mecklenburg megalithic graves. Investigations into their architecture and function (= contributions to the prehistory and early history of the districts of Rostock, Schwerin and Neubrandenburg. 6, ISSN 0138-4279 ). German Science Publishing House, Berlin 1972.

- Jürgen E. Walkowitz: The megalithic syndrome. European cult sites of the Stone Age (= contributions to the prehistory and early history of Central Europe. Vol. 36). Beier & Beran, Langenweißbach 2003, ISBN 3-930036-70-3 .

Web links

- [1] , among others, plan of passage grave of Gaarzerhof with three yokes (Jochbauweise) in the middle (private website)

- Ground plan of Møllehøj from Kyndeløse (Danish)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Urs Schwegler, Chronology and Regionality of Neolithic Collective Graves in Europe and Switzerland . Hochwald Librum 2016, 267. ISBN 978-3-9524542-0-6

- ↑ Urs Schwegler, Chronology and Regionality of Neolithic Collective Graves in Europe and Switzerland . Hochwald Librum 2016, 267. ISBN 978-3-9524542-0-6

- ↑ Urs Schwegler, Chronology and Regionality of Neolithic Collective Graves in Europe and Switzerland . Hochwald Librum 2016, 267. ISBN 978-3-9524542-0-6

- ↑ Reena Perschke: The German megalithic grave nomenclature - A contribution to dealing with ideologically loaded technical terminology. In: Archaeological Information . Vol. 39, 2016, pp. 167-176, doi : 10.11588 / ai.2016.1.33548 .

- ^ Karl-Göran Sjögren, Mortuary Practices, Bodies, and Persons in Northern Europe. In: Chris Fowler, Jan Harding, Daniela Hofmann (Eds.): The Oxford Handbook of Neolithic Europe . Oxford, Oxford University Press 2015. 10.1093 / oxfordhb / 9780199545841.013.017, 1007

- ↑ Chris Fowler, Chris Scarre, Mortuary Practices and Bodily Representations in North-West Europe. In: Chris Fowler, Jan Harding, Daniela Hofmann (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Neolithic Europe . Oxford, Oxford University Press 2015, 1027. DOI: 10.1093 / oxfordhb / 9780199545841.013.054

- ^ Glyn E. Daniel : The megalith builders of Western Europe (= Penguin books. A: Pelican books. A 633). Penguin, Harmondsworth 1963.

- ↑ The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs between the Baltic Sea and the Thuringian Forest (= contributions to the prehistory and early history of Central Europe. 1). Beier and Beran, Wilkau-Haßlau 1991, (at the same time: Halle, University, habilitation paper, 1991: The megalithic, submegalithic and pseudomegalithic buildings as well as the menhirs in the five new East German federal states (formerly GDR), an inventory).