Megalithic in the Netherlands

The Megalithic occurred in today's Netherlands during the Neolithic period on especially in the Northeast. Megalithic structures, i.e. structures made of large erect stones, come in various forms and functions, mainly as graves , temples or menhirs (stones standing alone or in formation). Only grave sites are known from the Netherlands. These large stone graves ( Dutch Hunebedden ) are between 3470 and 3250 BC. By members of the western group of the funnel cup culture(TBK) and until about 2760 BC. Has been used. The facilities were subsequently used after the end of the funnel beaker culture in the late Neolithic through the individual grave culture and the bell beaker culture , during the ensuing Early Bronze Age and, to a lesser extent, until the Middle Ages .

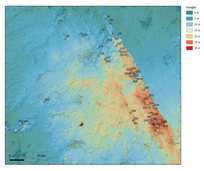

Of the originally more than 100 large stone graves in the Netherlands, 54 are still preserved today. Of these, 52 are in the province of Drenthe . Two more are in the province of Groningen , one of which has been converted into a museum. There is also a facility in the province of Utrecht , the classification of which as a large stone grave is uncertain. Destroyed megalithic graves are also known from the province of Overijssel . Most of the surviving graves are concentrated on the Hondsrug ridge between the cities of Groningen and Emmen .

The graves aroused the interest of researchers early on. The first treatise was published in 1547. A book by Johan Picardt , published in 1660 , who believed the graves to be buildings by giants , found widespread use . In 1685, Titia Brongersma carried out the first known excavation of a large Dutch stone grave. In 1734 a first law was passed to protect graves; this was followed by others in the 18th and 19th centuries. Leonhardt Johannes Friedrich Janssen presented an almost complete list of the graves for the first time in 1846. William Collings Lukis and Henry Dryden made the most precise plans of numerous graves in 1878. Modern archaeological research into the megalithic graves was initiated in 1912 by Jan Hendrik Holwerda , who completely excavated two structures. Shortly afterwards, Albert Egges van Giffen began further research. He measured all the facilities, carried out numerous other excavations and had almost all of the graves restored until the 1950s. Van Giffen also developed a numbering system that is still used today for the large stone graves, with a capital letter for the province and a number ascending from north to south (and a lower case letter for destroyed structures). Since 1967 there has been a museum in Borger , which is exclusively dedicated to the megalithic graves and their builders.

The chambers of the graves were made of granite - boulders built during the ice age were deposited in the Netherlands. The gaps between the stones were filled with dry stone masonry made of small stone slabs. The chambers were then covered with earth. Some of the mounds also have a stone surround. Depending on whether the access to the chamber is on a narrow or a long side, the graves are referred to as dolmens or passage graves . Almost all facilities in the Netherlands are passage graves, only one is a dolmen. The graves are similar in their basic structure, but vary greatly in size. The chamber length ranges from 2.5 m to 20 m. Small chambers were built in all construction phases, while larger chambers were only added in later phases.

Due to the unfavorable conservation conditions, only small remains of human bones could be recovered from the graves. Mainly it is corpse burn . Only very limited statements can be made about the age at death and the sex of the dead.

The additions, on the other hand, are very rich. Thousands of pottery fragments were found in some graves, which could often be reconstructed into hundreds of vessels. Other additions were stone utensils, jewelry in the form of pearls and pendants, animal bones and, in rare cases, objects made of bronze . The rich spectrum of shapes and decorations of the vessels made it possible to distinguish between several typological levels, which allow conclusions to be drawn about the history of the construction and use of the graves.

Research history

Early Research (16th-18th Century)

The modern study of the Dutch megalithic tombs began in 1547 with Anthonius Schonhovius Batavus (Antony van Schoonhoven), canon of St. Donatian's Cathedral in Bruges . In a manuscript he referred to a text passage in the Germania des Tacitus , in which " Pillars of Heracles " in the land of the Frisians are mentioned. Schonhovius equated this with one of the graves near Rolde and mixed the text of Tacitus with local legends. He assumed that the building material was brought by demons who were worshiped under the name Heracles . He also held the graves for altars on which human sacrifices were carried out. His text was taken up by numerous other scholars in the following decades and the pillars of Heracles or the "Duvels Kut" ("Teufelsfotze", another name that, according to Schonhovius, was used for the grave near Rolde), were used between 1568 and 1636 recorded on several maps.

It took more than a hundred years before someone wrote about the Dutch megalithic graves who had also personally inspected them. The from Bentheim originating Johan Picardt was among others in Rolde and Coevorden as Pastor worked and was also responsible for the Moorkolonisierung the border between Bentheim and Drenthe. In 1660 he published a three-part work on the antiquities of the Netherlands and in particular the province of Drenthe and the city of Coevorden. Picardt's views were heavily influenced by biblical stories. He took the hypothesis that the megalithic tombs were built by giants who finally immigrated to Drenthe from the Holy Land via Scandinavia . This view was widespread, not least because of the impressive illustrations in Picardt's book. At the same time, before and during Picard's lifetime, there were other (mainly German) researchers who rejected this idea and ascribed the construction of the graves to ordinary people. Furthermore, Picardt provided detailed descriptions of the structure of the graves for the first time and also mentioned ceramic vessels as additions.

A few years after Picardt, the lawyer and historian Simon van Leeuwen also visited the megalithic tombs in the province of Drenthe and dedicated a section to them in his work Batavia Illustrata, published posthumously in 1685 . Van Leeuwen also thought giants were conceivable as builders, but thought more of tall Cimbri and Celts .

From Dokkum Dating poetess Titia Brongersma led in 1685 by the first known excavation of a large stone grave in the Netherlands. Together with her cousin Jan Laurens Lentinck, the mayor of Borger , she organized the investigation of the large stone grave Borger (D27). Brongersma herself published only two poems about this, from which it emerges that she thought the tomb was a temple , which was dedicated to nature. She exchanged a lot about this with her friend, the doctor and poet Ludolph Smids from Groningen . For his part, Smids first wrote a poem about the excavation. In his work Poëzije he published these poems in 1694 and also added a more detailed description of the finds and findings from the grave. Smid's publication of the excavation in Borger and his correspondence with Christian Schlegel meant that the idea of giants as builders of the megalithic graves was increasingly rejected. Smids himself revised his views after his conversion from Catholicism to Calvinism and took up Picardt's views again in his 1711 work Schatkamer der Nederlandse oudheden .

In 1706 Johannes Hofstede and Abraham Rudolph Kymmel carried out another excavation on a large stone grave in Rolde (D17). Hofstede described in his report for the first time the different layers within the complex as well as the stratigraphic position of the ceramic found. Unfortunately, the report had no influence whatsoever on Hofstede's contemporaries, as it was not published until 1848.

In the 1730s, new dykes were built in large parts of the Netherlands and northwestern Germany , as the old ones were based on wooden structures that had been eaten away by imported shipworms . The new dykes consisted of stone-covered mounds of earth, which is why boulders have now become a popular building material. The completely unregulated search for boulders also led to boundary stones being removed. This prompted the government of Drenthe to pass a resolution on July 21, 1734 banning such acts. At the same time, this resolution placed the megalithic graves under protection. After two royal decrees in Denmark (1620) and Sweden (1630), this was the third law for the protection of antiquities in Europe.

In 1732, the wealthy Amsterdam textile merchant Andries Schoemaker took a trip to Drenthe together with the draftsman Cornelis Pronk and his pupil Abraham de Haen . The first realistic drawings of the two large stone graves near Havelte (D53 and D54) were made. Schoemaker also prepared a detailed description of the systems. Both draftsmen later returned to Drenthe. De Haen still has a drawing of the large stone grave D53 from 1737 and Pronk one of the large stone grave Midlaren (D3) from 1754.

In 1756 Joannes van Lier was commissioned with the restoration of the large stone grave Eext (D13). This facility, which was sunk into the ground, had been discovered by a stone seeker around 20 years earlier and was also rediscovered by stone seekers in 1756. The vessels and axes found in the process were sold to collectors. In addition, two cap stones were removed. Van Lier carried out a detailed examination of the complex and restored the burial chamber to its original state as well as possible. Just two days later he published a newspaper article about his work. Shortly afterwards, Cornelis van Noorde made a drawing of the grave. Henrik Cannegieter , Rector of the Latin School in Arnhem , wrote a treatise on the grave based on the newspaper article without ever looking at it himself or having contacted van Lier. At the suggestion of his friend Arnout Vosmaer , van Lier dealt critically with this treatise in five long letters. The first monographic treatise on a large Dutch stone grave emerged from these letters. It was published by Vosmaer in 1760.

Between 1768 and 1781, Petrus Camper made drawings of eight large stone graves, including the large stone grave Steenwijkerwold (O1) , which was destroyed in the 19th century .

In 1774 Theodorus van Brussel published a new edition of Ludolf Smids' Schatkamer of the Nederlandse oudheden and provided it with extensive comments of his own. Van Brussel took the view (obviously ignorant of van Lier's work) that the megalithic tombs were natural structures that had formed on the seabed and that after the land had dried up, they had their present-day appearance through erosion .

In 1790 Engelbertus Matthias Engelberts published the third volume of his historical work De Aloude Staat En Geschiedenissen Der Vereenigde Nederlanden, which was aimed at a wide audience . In it he devoted himself in detail to the megalithic graves and summarized the current state of research quite completely. He also added two (rather imprecise) drawings of the Tynaarlo (D6) large stone grave to his text . It is worth mentioning that he observed that the flat side of the capstones in the graves always points downwards. He therefore rejected the idea that the complexes served as altars.

In 1790 the resolution to protect the megalithic graves was renewed. In 1809 the Landdrost von Drenthe, Petrus Hofstede , again banned the removal of stones from the graves and digging in hills. In 1818/19 the local authorities were obliged to closely monitor compliance with this law and to draw up annual reports on it.

19th century

In 1808 the Royal Hollandsche Maatschappij der Wetenschappen initiated a competition on the initiative of Adriaan Giles Camper , the son of Petrus Campers, with the aim of clarifying the ethnic identity of the builders of the megalithic tombs.

In April 1809, the large rock grave Emmen-Noord (D41) , which had been completely hilly until then, was uncovered and examined. Johannes Hofstede , the brother of Petrus Hofstede, wrote a detailed report on this. His brother then obtained that Johannes Hofstede was granted the sole right to carry out excavations in the province of Drenthe. Later in the year he examined four other large stone graves. However, these excavations were not documented in more detail.

Nicolaus Westendorp made further important research contributions at the beginning of the 19th century. In 1811 he visited the megalithic graves in Drenthe and seven others in Germany . He wrote an extensive treatise with which he finally won the 1808 competition. Westendorp described a distribution area of megalithic systems that reached from Portugal to Scandinavia. He assumed a common origin for all of these plants. He took up the observation made by van Lier that the large stone graves only contained stone tools. On this basis, Westendorp argued for a two-period system consisting of a Stone Age and a subsequent Metal Age . The Danish researcher Christian Jürgensen Thomsen was heavily influenced by his work in developing his three-period system . Westendorp compared the inventories of the great stone graves with the material legacies of several ancient peoples and excluded most of them because of their use of metal tools. Since assignment to a previously unknown people was out of the question for him, he pleaded for early Celts as builders. He first published his theses in 1815 as an essay and in 1822 as a monograph. Westendorps work received a lot of attention, but also received criticism. For example, his Celtic hypothesis has been called into question, since large stone graves are missing in large parts of Central and Eastern Europe , even though these were inhabited by Celts.

In the 1840s, communal land was to be parceled out. For the megalithic graves there was again the danger of destruction, which is why Johan Samuel Magnin , provincial archivist of Drenthe, sent a petition to King Wilhelm II in 1841 , in which he demanded that ancient graves should be excluded from the privatization of the land. The petition was unsuccessful. Even a newspaper article by the doctor Levy Ali Cohen , published in 1842, did not result in a change in the law.

Furthermore, in the 1840s, two history books, which were quite popular at the time and aimed at a wide audience, were published in which a large room was devoted to the megalithic graves. In 1840 Johannes Pieter Arend published the first volume of his Algemeene Geschiedenis des Vaterland. He relied primarily on the work of Engelberts and Westendorp and saw the early Celts as the builders of the graves. Grozewinus Acker Stratingh, on the other hand, advocated the then new thesis in 1849 that the graves were built by ancestors of the Celts and Teutons who were not known by name .

The most important researcher in the mid-19th century was Leonhardt Johannes Friedrich Janssen (1806–1869), curator of the collection of Dutch antiquities in the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Leiden . His preoccupation with large stone graves began in 1843 when he had several models of the large stone grave Tynaarlo (D6) made for various museums. In 1846 he excavated the stone box from Exloo-Zuiderveld (D31a) and the large stone grave Zaalhof (D44a). In 1847 he studied the Dutch megalithic graves on site and published a paper on the subject the following year. Janssen thus presented for the first time an almost complete descriptive overview of the large stone graves still preserved in the Netherlands. In 1849 he carried out another excavation on the remains of the stone box in Rijsterbos (F1). Later he devoted himself to questions about the construction methods of the graves and the way of life of their builders. Janssen's biggest mistake was that the date of the systems was far too young. He described the ceramic finds as "Germanic" and considered the youngest graves to be Roman times . In 1853 he fell for the Hilversum worker Dirk Westbroek , who had faked several supposedly Stone Age hearths. In one of them there was a worked sandstone slab from the Middle Ages or the modern era , which Janssen dated Roman times and regarded as confirmation that the Stone Age in the Netherlands did not end until the Romans. Janssen's mistake shaped prehistory research in Leiden for many decades to come. It was not until 1932 that the stoves in Hilversum were exposed as fakes.

The writer Willem Hofdijk was strongly influenced by Janssen's work and wrote several works between 1856 and 1859 in which he sketched a vivid picture of the Dutch prehistoric times. An astonishing curiosity is his dating of the megalithic tombs , which he found in his work Ons Voorgeslacht (Our Ancestors) in the time around 3000 BC. Chr. Located. In general, they were considered to be significantly younger at that time, but Hofdijk assumed, probably more by chance, a date that roughly corresponds to today's knowledge.

In 1861 and 1867, illegal excavations caused severe damage to the large stone grave De Papeloze Kerk (D49). In order to prevent further destruction, all but one of the graves became property of the state or the province of Drenthe around 1870. At the suggestion of the amateur archaeologist Lucas Oldenhuis Gratama , several facilities were subsequently restored, but this was done in an unprofessional manner . Gratama took over an erroneous assumption from Westendorps that the graves originally had no mounds and therefore had them removed as supposed wind drifts without documentation.

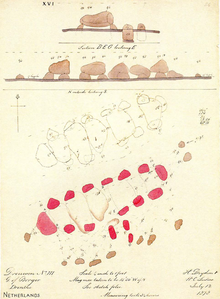

Augustus Wollaston Franks , curator at the British Museum , visited Drenthe in 1871 and was very disappointed with the unprofessional restoration of the megalithic tombs. At his suggestion, William Collings Lukis (1817–1892) and Henry Dryden (1818–1899) undertook a research trip to Drenthe in 1878 . Both had previously examined megalithic sites in the United Kingdom and Brittany and now produced very precise floor plans and sectional drawings of 40 large stone graves in the Netherlands as well as several watercolors of ceramic finds.

Willem Pleyte , Janssen's successor as curator at the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, published an extensive list of the archaeological sites in the Netherlands that were known at the time from 1877 onwards. He made extensive use of photography for the first time . The first known pictures of Dutch megalithic stone graves were made in 1870. In 1874 Pleyte went on a trip through Drenthe together with the photographer Jan Goedeljee and had all the megalithic graves photographed there. The photos served him as a template for lithographs . Apparently independent of Pleyte's work, Conrad Leemans , the director of the Rijksmuseum, made a trip to Drenthe in 1877 . Jan Ernst Henric Hooft van Iddekinge , who had already been there with Pleyte, made plans for the large stone graves for Leemans, but the quality of the plans did not come close to the work of Lukis and Dryden.

The realization that the Dutch megalithic tombs were part of a Stone Age culture that spanned large parts of northern and central Europe gradually took hold from the end of the 19th century. Nicolaus Westendorp had already noticed the great similarity to the graves in northwest Germany in 1815. Augustus Wollaston Franks noticed in 1872 that not only the graves but also the burials found were very similar to those from Germany and Denmark . In 1890 the Königsberg prehistorian Otto Tischler first established the existence of various regional groups within the funnel cup culture and narrowed down the distribution area of the western group more precisely. At the beginning of the 20th century, Gustaf Kossinna distinguished four regional groups based on ceramics: a north, west, east and south group. Konrad Jażdżewski was able to provide an even more detailed overview in the 1930s and also divide Kossinna's eastern group into an eastern and southeastern group.

20th and 21st centuries

At the beginning of the 20th century, the physician Willem Johannes de Wilde made important research contributions. In the years 1904–1906 he visited all the remaining large stone graves in the Netherlands, made plans, took photos and developed an extensive catalog of questions about the architecture of the individual facilities. Unfortunately, his records are incomplete.

A new phase of megalithic research in the Netherlands began in 1912 when the Leiden archaeologist Jan Hendrik Holwerda completely excavated the two large stone graves near Drouwen (D19 and D20). In the following year he examined the large stone grave Emmen-Schimmeres (D43).

Shortly after Holwerda, the Groningen archaeologist Albert Egges van Giffen carried out further excavations. His work was to shape megalithic research in the Netherlands for several decades. In 1918 he completely excavated the large stone grave Havelte 1 (D53), a large stone grave near Emmerveld (D40), the large stone grave Exloo-Noord (D30) and two large stone graves near Bronneger (D21 and D22) and made test excavations at the large stone grave Drouwenerveld (D26) Large stone grave Balloo (D16) and another large stone grave near Emmerveld (D39). Furthermore, between 1918 and 1925, he examined the remains of three destroyed facilities: the Steenwijkerwold stone grave (O1), the stone box in Rijsterbos (F1) and the Weerdinge stone grave (D37a). In addition, he re-measured all the remaining systems in the Netherlands and published his De Hunebedden work in Nederland, which consists of two volumes of text and an atlas volume, in 1925-27 . For this he developed the numbering system still used today for the graves with a capital letter for the province followed by a number increasing from north to south (as well as an appended lower case letter for destroyed facilities). In 1927 van Giffen dug two more graves: The large stone grave Buinen-Noord (D28) and the large stone grave Eexterhalte (D14). In the 1940s he examined the remains of several destroyed facilities.

During the Second World War , the stones of the Havelte 1 (D53) large stone grave were buried and a runway was built at its location. The airfield was bombed in 1944 and 1945. After the war, the facility was rebuilt in its original location.

In the 1950s, van Giffen mainly devoted himself to the restoration of the graves. He made missing wall stones recognizable by having their stand holes filled with concrete . In 1952 he carried out an excavation at the large stone grave Annen (D9) and in 1957 together with Jan Albert Bakker at the large stone grave Noordlaren (G1) and 1968-1970 with Jan Albert Bakker and Willem Glasbergen at the large stone grave Drouwenerveld (D26).

Van Giffen had the idea for a museum specifically dedicated to the megalithic graves and their builders in 1959. The exhibition developed by Diderik van der Waals and Wiek Röhling was presented from 1967 in a restored farmhouse in Borger. Unfortunately, the house burned down twice and the museum was finally relocated to the former poor house near the Borger stone grave (D27). In 2005, a newly built visitor center with open-air facilities was opened at this location under the name Hunebedcentrum .

Jan N. Lanting carried out further excavations between 1969 and 1993. He examined the remains of several destroyed facilities, most of which had been discovered by the amateur archaeologist Jan Evert Musch . Lanting also examined the Heveskesklooster stone grave , which was only discovered in 1982 and converted into a museum in 1987.

In the 1970s, Jan Albert Bakker presented his dissertation , which is still an authoritative overview of the western group of the funnel beaker culture. The then known grave inventories of the Dutch large stone graves made up an essential part of his database. In 1992 he published a monograph on the architecture of the graves and in 2010 another on the history of research.

Anna L. Brindley was able to develop a seven-step internal chronology system for the funnel cup west group based on the extensive ceramic finds from the large stone graves in the 1980s.

The few bone remains known from the Dutch graves have not been systematically examined for a long time. This only changed in the years 2012-2015, when Liesbeth Smits and Nynke de Vries those found in the megalithic tombs cremations were evaluating.

In 2017, all large stone graves in the Netherlands were recorded in a 3D atlas using photogrammetry . The data was obtained from the Gratama Foundation through a collaboration between the Province of Drente and the University of Groningen .

Existence and distribution

It is not known how many large stone graves there were originally in the Netherlands. Their number is likely to have been over 100. 53 graves are still preserved today. There is also one that has been converted into a museum and a stone complex, which is questionable as to whether it is the remains of a large stone grave. Furthermore, 23 destroyed graves are known about which reliable information is available. Jan Albert Bakker also lists nine possible sites about which only vague information is available from older literature and whose classification as large stone graves is uncertain (he does not consider information on 19 other sites to be reliable). Bert Huiskes was 96 also for the province of Drenthe field names identify which indicate possible destroyed megalithic tombs.

The large stone graves of the Netherlands were built by members of the funnel cup culture. This is a Neolithic cultural complex that dates back to 4100 BC. Spread from Denmark over large parts of Europe and until 2800 BC. Chr. Had existed. The funnel beaker culture was divided into several regional groups that were spread from central Sweden in the north to the Czech Republic in the south and from the Netherlands in the west to Ukraine in the east. Megalithic tombs were not common in the entire area of distribution, but limited to Scandinavia , Denmark, northern and central Germany , northwestern Poland and the Netherlands. The Dutch large stone graves are counted together with the facilities of western Lower Saxony to the western group of the funnel beaker culture. The original total number of graves is difficult to estimate. About 20,000 systems are known that are still preserved or about which reliable information is available (of which over 11,600 in Germany, 7,000 in Denmark and 650 in Sweden). The total number of all large stone graves of the funnel beaker culture ever erected is likely to have been at least 75,000, perhaps it was even up to 500,000. The Dutch graves thus form a comparatively small group on the far western edge of the funnel cup culture.

The preserved graves are all in the provinces of Drenthe and Groningen. The largest part is concentrated on a strip running from north-north-west to south-south-east on the Hondsrug ridge between the cities of Groningen and Emmen . Almost all of these graves can be reached via the N34 road. Three plants are located some distance west of the main group at Diever and Havelte . The locations of several destroyed plants are loosely scattered between them and the main group. In the north of the province of Groningen, near the coast, was founded in 1983 in the church today Eemsdelta under a mound , the stone grave Heveskesklooster (G5) discovered and the Muzeeaquarium Delfzijl implemented.

Two large stone graves are known to have been destroyed in the province of Overijssel . The large stone grave Steenwijkerwold (O1) was located in the very north of the province, about 8 km from the two large stone graves near Havelte (D53 and D54). In the east of the province, near the German border, there was the Mander stone grave (O2). The megalithic graves were located a few kilometers to the north near Uelsen in the Grafschaft Bentheim district in Lower Saxony .

Far away from the other plants, in the north of the province of Utrecht, lies the stone from Lage Vuursche (U1). If it were the remains of a large stone grave, it would be the southernmost and westernmost in the Netherlands as well as the westernmost megalithic tomb in the area where the funnel cup culture is distributed.

Bakker also believes that it is possible that there could have originally been megalithic graves in the province of Gelderland , since megalithic graves are also known from the neighboring region to the east, northern North Rhine-Westphalia .

| province | obtain | implemented | destroyed | questionable / received |

questionable / destroyed |

Field name references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drenthe | 52 | 18th | 8th | 96 | ||

| Groningen | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||

| Overijssel | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Utrecht | 1 |

Grave architecture

Grave types

The large stone graves of the funnel beaker culture have overhanging burial chambers built from boulders and are divided into several types based on various characteristics. The main feature is the position of the access to the burial chamber. If it is on a long side, one speaks of a passage grave . The counterpart to this is the dolmen , which has an access on one narrow side or, in the case of very small structures (the primeval dolmen ), has no access at all. The number of gangue stones as well as the shape of the mound and the presence or absence of a stone enclosure are used as further classification features.

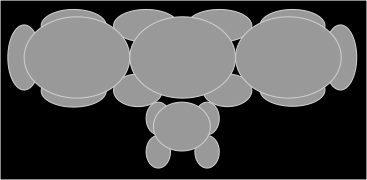

Of the 54 preserved structures in the Netherlands, 52 are safe or have a high probability of being identified as passage graves (another one is too badly damaged for a safe classification). Albert Egges van Giffen distinguished between four sub-types:

- The "ganggraf" (passage grave): Van Giffen only referred to those graves as such with a stone enclosure and a covered passage in front of the entrance.

- The "portaalgraf" (portal grave): By this, van Giffen meant those graves whose access is preceded by a pair of gangestones without a capstone.

- The "trapgraf" (stepped grave): This refers to systems sunk into the ground, the grave chambers of which are not accessible through a horizontal corridor, but through a stone staircase. The only example of this type in the Netherlands is the large stone grave Eext (D13). In the rest of the distribution area of the funnel beaker culture, graves with such an access construction are rare. Only four examples from Lower Saxony (the large stone grave Deinste 1 , the large stone grave Krelingen , the large stone grave Sieben Steinhäuser C and the destroyed large stone grave Meckelstedt 2 ) are known to be comparable.

- The "long count" (long grave): Thus, a system is with a long barrow meant that encloses several grave chambers. The only example of this type in the Netherlands is the Emmen-Schimmeres large stone grave (D43). Similar systems from Lower Saxony are also known for this type, such as the Hünenbett A in Daudieck , the Großsteingrab Kleinenkneten II or the Großsteingrab Tannenhausen .

- Schematic representation of the passage grave types according to van Giffen

In more recent literature (for example in Bakker) these terms van Giffens are no longer used and all these facilities are instead only referred to as passage graves. In Lower Saxony, the name Emsland Chamber was coined for a sub-form of the passage grave, which is typical for the western group of the funnel cup culture. A large number of the Dutch passage graves also correspond to this type. The Emsland Chamber is characterized by a comparatively long, mostly east-west oriented burial chamber with an entrance on the southern long side, which is enclosed at a short distance by a stone enclosure.

The big exception among the Dutch facilities is the relocated Heveskesklooster (G5) stone grave , which is the only known dolmen (more precisely a large dolmen ) in the country. It consists of three pairs of wall stones on the long sides, a capping stone on the northern narrow side and three cap stones. The entrance is on the open southern narrow side.

Smaller tombs, the chambers of which are mostly sunk into the ground and made of small-format stone slabs, are known as stone boxes. Some specimens from the time of the funnel beaker are also known from the Netherlands. These facilities are generally not counted among the megalithic graves.

Hill fill and enclosure

Originally, all graves were filled with mounds. This was round for smaller systems and oval for larger ones. Only the large stone grave Emmen-Schimmeres (D43) has a different shape. Here the two burial chambers lie in a slightly trapezoidal long bed with rounded narrow sides and a stone enclosure. Wrapping was also found in eight or nine other systems. These are always larger systems with a chamber length of 8 m and more.

Burial chamber

orientation

In most of the passage graves, the burial chambers are oriented roughly in an east-west direction and the access points to the south. There are large scatterings from northeast-southwest to southeast-northwest, but in almost all chambers the ends lie within the extreme points of the rising and setting of the sun and moon . However, six chambers deviate from this and are oriented between south-south-east-north-north-west and south-south-west-north-north-east.

Chamber size and number of stones

The size of the chambers varies greatly. The shortest chamber with an inner length of 2.5 m has the large dolmen of Heveskesklooster (G5). The smallest passage grave was the destroyed large stone grave Glimmen-Zuid (G3) with an inner chamber length of 2.7 m and an outer length of 3.2 m. The largest grave chamber has the large stone grave Borger (D27). It has an inner length of 20 m and an outer length of 22.6 m and a width of 4.1 m.

The number of pairs of wall stones on the long sides is between two and ten, the number of cap stones between two and nine.

Chamber shape

The grave chambers of the passage graves mostly have a slightly trapezoidal floor plan and are slightly wider on the left side as seen from the entrance than on the right. Albert Egges van Giffen was able to measure 36 chambers in this regard and found a corresponding shape in 29. The difference in latitude varies quite a lot. In most graves, it is between 7 cm and 50 cm, three chambers, however, have a significantly larger difference in width of 87 cm, 88 cm and 106 cm. Of the remaining seven chambers measured, five are wider at the right end than at the left. Here the difference in width is only between 9 cm and 21 cm. With two chambers, both ends are exactly the same width.

Access

In almost all cases, access to the chambers is in the middle of the southern or eastern long side of the passage graves. In the graves with three to five pairs of wall stones, the entrances are usually slightly offset to the right. More rarely, they are exactly in the middle and in two cases they are shifted slightly to the left. Of the seven graves with seven pairs of wall stones, four have access more or less exactly in the middle, one is offset to the left and one to the right. In the case of the graves with nine or ten pairs of wall stones, the entrances are also in the middle or slightly offset to the right. A noticeable deviation from this construction method can only be found in the Emmen-Noord large stone grave (D41). This has four pairs of wall stones and the access is here at the western end of the southern long side between the first and the second wall stone.

The access to the chamber consists either of a simple opening between two wall stones or a corridor in front of it, which typically has one or two pairs of wall stones. Only one grave has a corridor with three pairs of wall stones. Longer corridors, such as are typical for the large stone graves of the funnel-shaped northern group, do not occur in the Netherlands.

At the Großsteingrab Eext (D13) a staircase leads to the entrance instead of a corridor. According to van Lier's investigation in 1756, this consisted of four steps, each of which consisted of one or two flat stone slabs and were bordered by two walls made of rolling stones. At the bottom of the stairs, directly in the entrance to the chamber, was a threshold stone . In 1927 Albert Egges van Giffen found only remnants of this staircase construction.

The chamber floor

The floor of the burial chambers usually consists of several layers of different stones. The top layer consists of burnt granite - grus . This was followed by sandstone slabs or rubble of round or flat shape. In some of the graves there seems to have been another layer of stones underneath. The floors are usually not even, but rather sink slightly towards the middle. The height differences are up to 50 cm.

In the funnel cup north group, the burial chambers are often divided into several quarters by stone slabs set vertically into the ground. In the western group this is seldom the case and for the Netherlands this is only known from one grave. In the northern large stone grave near Drouwen (D19), Jan Hendrik Holwerda found a row of three 70 cm long and 30 cm high slabs at the north-western end of the chamber, which separated a small room 2 m wide and 1 m long.

Drywall

The gaps between the wall stones of the chambers were originally filled from the outside with dry masonry made of horizontally laid stone slabs. Only remnants of this are preserved today. The maximum preserved height of the masonry was 1.4 m in the large stone grave Bronneger 1 (D21). In some very long chambers, larger gaps were not completely filled with dry masonry, but smaller upright boulders were also built in, which had no capstone.

Burials

In contrast to many other areas with megalithic tombs, hardly any organic materials have been preserved in the Dutch megalithic tombs. This also applies to the bones of those buried here. During his examination of the two systems in Drouwen, Jan Hendrik Holwerda was able to find poorly preserved remains of human skeletons in grave D19. Mainly it was teeth and remains of jawbones.

The remains of corpse burns were found in 26 graves . In some cases only a few grams were preserved, but more than 1 kg each could be recovered from the two large stone graves in Havelte (D53 and D54) and the destroyed large stone grave Glimmen 1 (G2). The total weight of the corpse burns recovered from all Dutch large stone graves is just under 8 kg. In most cases the bone fragments could only be assigned to individual individuals, but five individuals could also be distinguished in two graves. A total of 48 individuals could be identified.

Bones from several graves have been dated using radiocarbon dating, which confirms that they come from funnel-shaped burials.

Only limited statements can be made about the sex and age of death of the buried, as both could not or only imprecisely be determined for the majority of individuals. According to the evaluation by Nynke de Vries, there is likely to be a slight surplus of men among the dead. Most of the individuals died in adulthood. Funerals of children and young people make up only a small part.

Additions

Ceramics

By far the largest part of the funnel-shaped grave goods make up ceramic vessels. The largest number comes from the large stone grave Havelte 1 (D53). The fragments found here could be reconstructed into 649 vessels. The destroyed large stone grave Glimmen 1 (G2) contained around 360 vessels and the large stone grave Drouwenerveld (D26) 157.

The spectrum of shapes of ceramics is quite diverse. The funnel beaker , a bulbous vessel with a long funnel-shaped neck, gives its name to the culture of the large stone diggers . Similar vessels with eyelets on the neck and shoulder fold are called eyelet or ceremonial beakers. Collar bottles are small, bulbous bottles with a widening below the mouth. Amphorae are bulbous vessels with a short cylindrical rim. The eyelet or dolmen bottle has a funnel-shaped neck that can be very long in some specimens. There are one or two pairs of eyelets on the neck-shoulder wrap. A similar vessel shape is the eyelet cup, in which the eyelets are close to the bottom. Jugs are tripartite and have a funnel-shaped rim and one or two handles. Shoulder cups have the same structure as jugs, but are wider than they are tall. Steep-walled cups have a straight wall that widens slightly towards the top. Shells with straight or convex walls and sumps also occur. Fruit or foot shells consist of a convex or funnel-shaped neck and a stand. Both can be connected by one or two handles. Grooved neck vessels are two-part flat shells with a conical rim. They only appear in the late phase of the funnel beaker culture. Nozzle cups consist of a bowl and an attached hollow nozzle. Instead of the spout, spoons have a solid handle. Both forms are not always easy to distinguish (especially when they are broken up). Flat ceramic disks, called baking plates, are also used. Forms that have only been assigned once are a spindle-like object and a model of a stool or a throne.

- Ceramics

Stone tools

Other common additions are flint implements . These include hatchets , cross-edged arrowheads , scrapers , blades and tees . The sheeters represent the largest group in terms of numbers. Hatchets, axes and hammers made of rock are rare. A club head is only occupied once .

- Stone tools

Jewellery

In the found items of jewelery are beads made of amber most common. Occasionally there are also pearls made of gagat and quartz as well as pendants made of perforated fossils .

- Jewellery

perforated trilobite , grave D43

metal

Metal finds are a rare group of objects. In the large stone grave Drouwen 1 (D19) strips were found, in the large stone grave Buinen 1 (D28) spirals and in the large stone grave Wapse (D52a) a sheet of copper or arsenic bronze . These are the oldest metal finds in the Netherlands.

- Metal finds

Animal bones

Small remains of mostly burned animal bones were found in 20 large stone graves. Bones from domestic pigs , domestic cattle , sheep / goats , horses , canids , bears , red deer and possibly deer were represented . Most of them were probably used as tools, but at least one bone appears to have come from a food offering. Since only claws were found from the bear , it could be the remains of a bearskin that was used to wrap a person before the cremation.

Laying down in front of the graves

In front of the entrances to several large stone graves , deposits of ceramic vessels and stone implements from the time of the funnel beaker were found, for example at the large stone grave Drouwenerveld (D26) and the large stone grave Eexterhalte (D14). Even when the mounds of the two large stone graves near Midlaren (D3 and D4) were removed around 1870, corresponding ritual pits were probably uncovered but not recognized as such. The pottery is very similar in quality and style to the one found in the burial chambers and also dates to the same time. Storage vessels and baking plates as well as flint scratches are missing in the deposits.

Dating of the funnel beaker usage phases

On the basis of the range of shapes and decorations of the ceramic vessels found, several typological levels can be distinguished within the Funnel Beaker Western group, which at the same time indicate different phases of use of the large stone graves. Important older works on this come from Heinz Knöll and Jan Albert Bakker. The typological system that is still relevant today was developed in the 1980s by Anna L. Brindley. By comparing it with a large amount of 14 C data , Moritz Mennenga was able to present the most precise absolute chronological dating of these levels to date.

| horizon | Brindley | Period of time | Mennenga | Period of time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3350-3300 BC | about 50 years | 3470-3300 BC | about 200 years |

| 2 | 3300-3250 BC | about 50 years | ||

| 3 | 3250-3125 BC | approx. 125 years | 3300-3250 BC | about 50 years |

| 4th | 3125-2975 BC | about 150 years | 3250-3190 BC | about 60 years |

| 5 | 2975-2850 BC | approx. 125 years | 3190-3075 BC | approx. 115 years |

| 6th | 2850-2800 BC | about 50 years | 3075-2860 BC | approx. 215 years |

| 7th | 2800-2750 BC | about 50 years | 2860-2760 BC | about 100 years |

Level 1 pottery was the oldest found material found in five graves. These are exclusively small systems with 2–5 pairs of wall stones, chamber lengths between 2.7 m and 6.1 m, round or oval mound embankments without surrounds and access with a pair of gang stones or without gang stones. The establishment of seven or eight other graves was carried out during Stage 2. These also had some small chambers, but now it emerged larger chambers with up to seven Masonry pairs and lengths up to 12.4 m. In the large stone grave Drouwenerveld (D26) and the megalithic grave Emmen-Schimmeres (D43) with its two burial chambers can be seen for the first time a stone enclosure. All other graves of this level still have a pile of mounds without an enclosure. The marriage of the construction of the large stone graves falls in stage 3. In 13 graves, the corresponding ceramics are the oldest finds. Furthermore, both small and large systems were built. The chambers now had up to ten pairs of wall stones and lengths of up to 17 m. Mound embankments were built with or without enclosure and the entrances had zero to two pairs of wall stones. After level 3, no new large stone graves seem to have been built. However, large quantities of ceramics prove that almost all facilities up to level 5 were used continuously. After that, many graves were abandoned. Level 6 and 7 ceramics were only found in a few plants. For some graves, an interruption in use can also be proven. For example, the destroyed large stone grave Glimmen 1 (G2) was used during levels 3–5, abandoned in level 6 and used again in level 7.

Re-use of the graves

Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age

Burials

In most of the Dutch large stone graves , in addition to the funnel-beaker-time additions, vessels and stone utensils of the single grave culture and the bell- beaker culture (both late Neolithic ) and the early Bronze Age winding cord ceramics were found. These finds are generally regarded as additions from subsequent burials . It is noticeable, however, that in addition to the usual grave ceramics of this time, large amphorae and storage vessels were found that are otherwise only known from settlements, but are almost completely absent in individual graves. The megalithic graves therefore seem to have been used for special burials.

Cup stones

In prehistoric times, small circular bowls were attached to several large stone graves in the Netherlands . During an investigation in 2018, Mette van de Merwe identified seven plants with such machining operations. In five cases the bowls are on top stones, in one case on a wall stone and in another case on a surrounding stone. The exact purpose of these bowls is unknown. There is also no concrete evidence of their time in the Dutch graves. A comparison with other regions is therefore necessary. During his investigations into the megalithic stone graves in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Ewald Schuldt found no evidence that the bowls there had been attached by members of the funnel cup culture. They seem to be younger, as they were discovered in several cases in places that were probably only accessible again after the burial chambers had fallen into disrepair for a certain period of time. In Schleswig-Holstein, on the other hand, several large stone graves with bowls are known, which were rebuilt in the late Neolithic and the Bronze Age and used for new burials. For Jan Albert Bakker, all of this suggests that the bowls can be dated to the Late Neolithic and the Early Bronze Age.

Middle Bronze Age to Middle Ages

After the early Bronze Age, the megalithic tombs seem to have hardly been used, as finds from more recent times are very rare. In the destroyed large stone grave Spier (D54a) a notched-carved Bronze Age urn was found. A razor from the Middle Bronze Age comes from the large stone grave in Westenesch-Noord (D42) and a vessel from the Iron Age Harpstedter group from the large stone grave in Drouwenerveld (D26) . In 1750 a Roman silver coin is said to have been found in the large stone grave Eexterhalte (D14) . Around 1800 a boat model was found in the large stone grave Loon (D15), which probably dates to the early Middle Ages. Two similar specimens are of unknown origin. Some early to high medieval vessels are also likely to have come from large stone graves.

literature

Complete overview

- Theo ten Anscher : An inventarisatie van de documentatie relevant de Nederlandse hunebedden (= RAAP report. Volume 16). Stichting RAAP, Amsterdam 1988 ( online ).

- Jan Albert Bakker : The TRB West Group. Studies in the Chronology and Geography of the Makers of Hunebeds and Tiefstich Pottery (= Cingula. Volume 5). Universiteit van Amsterdam, Amsterdam 1979, ISBN 978-90-70319-05-2 ( online ).

- Jan Albert Bakker: A list of the extant and formerly present hunebedden in the Netherlands. In: Palaeohistoria. Volume 30, 1988, pp. 63-72 ( online ).

- Jan Albert Bakker: The Dutch Hunebedden. Megalithic Tombs of the Funnel Beaker Culture. (= International Monographs in Prehistory. Archaeological Series. Volume 2). International Monographs in Prehistory, Ann Arbor 1992, ISBN 1-87962-102-9 .

- Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. From 'Giant's Beds' and 'Pillars of Hercules' to accurate investigations , Sidestone Press, Leiden 2010, ISBN 9789088900341 ( online version ).

- Jan Albert Bakker: TRB megalith tombs in the Netherlands. In: Johannes Müller, Martin Hinz, Maria Wunderlich (eds.): Megaliths - Societies - Landscapes. Early Monumentality and Social Differentiation in Neolithic Europe. Proceedings of the international conference “Megaliths - Societies - Landscapes. Early Monumentality and Social Differentiation in Neolithic Europe "(16th – 20th June 2015) in Kiel (= Early Monumentality and Social Differentiation. Volume 18/1). Habelt, Bonn 2019, ISBN 978-3-7749-4213-4 , pp. 329–343 ( online ).

- Augustus Wollaston Franks : The megalithic monuments of the Netherlands and the means taken by the government of that country for their preservation. In: Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of London. 2nd series. Volume 5, 1872, pp. 258-267.

- Albert Egges van Giffen : De Hunebedden in Nederland. 3 volumes. Oosthoek, Utrecht 1925–1927.

- Albert Egges van Giffen: Opgravingen in Drente. In: J. Poortman (Ed.): Drente. En handboek voor het know about the Drentsche leven in voorbije eeuwen. Volume 1. Boom & Zoon, Meppel 1944, pp. 393-568.

- Evert van Ginkel : De Hunebedden. Gids En Geschiedenis Van Nederlands Oudste Monuments. Drents Museum, Assen 1980, ISBN 978-9070884185 .

- Evert van Ginkel, Sake Jager, Wijnand van der Sanden: Hunebedden. Monuments van een Steentijdcultuur. Uniepers, Abcoude 2005, ISBN 90-6825-333-6 .

- RHJ Klok: Hunebedden in Nederland. Zorgen voor tomorrow. Fibula-Van Dishoeck, Haarlem 1979.

- G. de Leeuw: Onze hunebedden. Gids in front of Drentse hunebedden en de Trechterbekerkultuur. Flint 'Nhoes, Borger 1984.

- William Collings Lukis : Report on the hunebedden of Drenthe, Netherlands. In: Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of London. 2nd series. Volume 8, 1878, pp. 47-55 ( online ).

- Wijnand van der Sanden, Hans Dekker: Gids voor de hunebedden in Drenthe en Groningen. WBooks, Zwolle 2012, ISBN 978-9040007040 .

- J. Wieringa: Iets over de ligging van de hunebedden op het zuidelijk deel van de Hondsrug. In: Nieuwe Drentse Volksalmanak. 1968, pp. 97-114.

- Willem Johannes de Wilde : De hunebedden in Nederland. In: De Kampioen. Volume 27, 1910, pp. 242-244, 256-258, 277-280.

Individual graves

- Jan Albert Bakker: Het hunebed G1 te Noordlaren. In: Groningse Volksalmanak. 1982-1983 (1983), pp. 113-200.

- Jan Albert Bakker: A dolmen bottle and a dolmen from Groningen. In: Jürgen Hoika (Ed.): Contributions to the early Neolithic funnel cup culture in the western Baltic region. 1st International Funnel Beaker Symposium in Schleswig from March 4th to 7th, 1985 (= studies and materials on the Stone Age in Schleswig-Holstein and in the Baltic Sea region. Volume 1). Wachholz, Neumünster 1994, ISBN 3-529-01844-9 , pp. 71-78.

- Jan Albert Bakker: Hunebed de Duvelskut bij Rolde. In: Nieuwe Drentse Volksalmanak. Volume 119, 2002, pp. 62-94.

- Jan Albert Bakker: De Steen en het Rechthuis van Lage Vuursche. In: Tussen Vecht en Eem. Volume 23, 2005, pp. 221-231 ( PDF; 8.5 MB ).

- Jan Albert Bakker: Augustus 1856: George ten Berge tekent de hunebedden bij Schoonoord, Noord-Sleen en Rolde. In: Nieuwe Drentse Volksalmanak. Volume 129, 2012, pp. 211-223.

- J. Boeles: Het hunebed te Noordlaren. In: Groningse Volksalmanak voor 1845. 1844, pp. 33-47.

- H. Bouman: Twee vernielde Hunebedden te Hooghalen. Dissertation, Groningen 1985.

- Anna L. Brindley : The Finds from Hunebed G3 on the Glimmer Es, mun. of Haren, province of Groningen, The Netherlands. In: Helinium. Volume 23, 1983, pp. 209-216 ( online ).

- Anna L. Brindley: Hunebed G2: excavation and finds. In: Palaeohistoria. Volume 28, 1986, pp. 27-92 ( online ).

- Anna L. Brindley: Meer aardewerk uit D6a / Tinaarlo (Dr). In: Paleo-aktueel. Volume 11, 2000, pp. 19-22 ( online ).

- Anna L. Brindley, Jan N. Lanting : A re-assessment of the hunehedden O1, D30 and D40: structures and finds. In: Palaeohistoria. Volume 33/34 1991/1992 (1992), pp. 97-140 ( online ).

- Anna L. Brindley, Jan N. Lanting, AD Neves Espinha : Hunebed D6a near Tinaarlo. In: Palaeohistoria. Volume 43/44, 2001/2002 (2002), pp. 43-85 ( online ).

- Anna L. Brindley, AD Neves Espinha: Vroeg TRB-aardewerk uit hunebed D6a bij Tinaarlo (Dr). In: Paleo-aktueel. Volume 10, 1999, pp. 21-24 ( online ).

- Nynke Delsman : Van offer tot opgraving: Meer informatie over hunebed D42-Westenesch-Noord (gemeente Emmen). In: Paleo-aktueel. Volume 27, 2016, pp. 7-11 ( online ).

- Albert Egges van Giffen: Mededeeling omtrent onderzoek en restauratie van het Groote Hunebed te Havelte. In: Nieuwe Drentsche Volksalmanak. Volume 37, 1919, pp. 109-139.

- Albert Egges van Giffen: De zgn. Eexter grafkelder, hunebed D XIII, te Eext, Gem. Anloo. In: Nieuwe Drentsche Volksalmanak. Volume 61, 1943, pp. 103-115.

- Albert Egges van Giffen: Het Ndl. Hunebed (DXXVIII) te Buinen, Gem. Borger, een bijdrage tot de absolute chronology of the Nederlandsche Hunebedden. In: Nieuwe Drentsche Volksalmanak. Volume 61, 1943, pp. 115-138.

- Albert Egges van Giffen: De twee vernielde hunebedden, DVIe en DVIf, bij Tinaarloo, Gem. Vries. In: Nieuwe Drentsche Volksalmanak. Volume 62, 1944, pp. 93-112.

- Albert Egges van Giffen: Een steenkeldertje, DXIIIa, te Eext, Gem. Anloo. In: Nieuwe Drentsche Volksalmanak. Volume 62, 1944, pp. 117-119.

- Albert Egges van Giffen: Twee vernielde hunebedden, DXIIIb en c, te Eext, Gem. Anloo. In: Nieuwe Drentsche Volksalmanak. Volume 62, 1944, pp. 119-125.

- Albert Egges van Giffen: Een vernield hunebed DXLIIa, het zoogenaamde Pottiesbargien, in het (vroegere) Wapserveld bij Diever, according to Diever. In Nieuwe Drentse Volksalmanak. Volume 64, 1946, pp. 61-71.

- Albert Egges van Giffen: Het grote hunebed D53. In Nieuwe Drentse Volksalmanak. Volume 69, 1951, pp. 102-104.

- Albert Egges van Giffen: On the question of the uniformity of the giant beds. The giant stone long grave near Emmen, Prov. Drenthe. In: Peter Zylmann (Ed.): On the prehistory and early history of Northwest Germany. New investigations from the area between the IJssel and the Baltic Sea. Festschrift for the 70th birthday of Karl Hermann Jacob-Friesen. Lax, Hildesheim 1956, pp. 97-122.

- Albert Egges van Giffen: Een reconstrueerd hunebed. Het gereconstrueerde ganggraf D49, "De Papeloze Kerk" bij Schoonoord, according to Sleen, prov. Drente. In: Nieuwe Drentse Volksalmanak. Volume 81, 1961, pp. 189-198.

- Albert Egges van Giffen: Restauratie en onderzoek van het langgraf (D43) te Emmen (Dr.). In: Helinium. Volume 2, 1964, pp. 104-114.

- Albert Egges van Giffen: De Papeloze kerk. Het bereonstrueerde Rijkshunebed D49 bij Schoonoord, according to Sleen. Wolters-Noordhoff, Groningen 1969.

- Annelou van Gijn , Joris Geuverink , Jeanet Wiersma , Wouter Verschoof : Hunebed D6 in Tynaarlo (Dr.): méér dan een berg grijze stenen? In: Paleo-aktueel. Volume 22, 2011, pp. 38-44 ( online ).

- Henny A. Groenendijk: De herontdekking van het hunebed op de Onner es. In: Historically jaarboek Groningen. 2014. p. 138.

- Henny A. Groenendijk, Jan N. Lanting, H. Woldring: The search for the lost large stone grave G4 'Onner es' (Onnen, Prov. Groningen). In: Palaeohistoria. Volume 55/56, 2013/14, pp. 57-84 ( online ).

- DJ de Groot: Hunebed D9 at Annen (gemeente Anlo, province of Drenthe, the Netherlands). In: Palaeohistoria. Volume 30, 1988, pp. 73-108 ( online ).

- Jan Hendrik Holwerda : Opgraving van twee hunnebedden te Drouwen. In: Oudheidkundige Mededelingen uit het Rijksmuseum van Oudheden te Leiden. Volume 7, 1913, pp. 29-50.

- Jan Hendrik Holwerda: Two huge rooms near Drouwen (Prov. Drente) in Holland. In: Prehistoric Journal. Volume 5, 1913, pp. 435-448.

- Jan Hendrik Holwerda: The big stone grave near Emmen (Prov. Drente) in Holland. In: Prehistoric Journal. Volume 6, 1914, pp. 57-67.

- Eva C. Hopman: A biography of D49, the “Papeloze Kerk” (Schoonoord, Dr.). 2011 ( online ).

- B. Kamlag: Hunebed D32d de Odoorn. Dissertation, Groningen 1988.

- Albert E. Lanting : Van heinde en ver? Een opmerkelijke pot uit hunebed D21 te Bronneger, according to Borger. In Nieuwe Drentse Volksalmanak. Volume 100, 1983, pp. 139-146.

- Jan N. Lanting: De hunebedden op de Glimmer Es (according to Haren). In: Groningse Volksalmanak. 1974-1975 (1975), pp. 167-180.

- Jan N. Lanting: Het na-onderzoek van het vernielde hunebed D31a bij Exlo (Dr.). In: Paleo-Aktueel. Vol. 5, 1994, pp. 39-42 ( online ).

- Jan N. Lanting: Het zogenaamde hunebed van Rijs (Fr.). In: Paleo-Aktueel. Volume 8, 1997, pp. 47-50.

- Jan N. Lanting: What is he werkelijk bekend over Hunebed D12, respectievelijk de schreden en kompasrichtingen bij Van Lier? In: Jan N. Lanting: Critical nabeschouwingen. Barkhuis, Groningen 2015, ISBN 978-94-91431-81-4 , pp. 65-88.

- Jan N. Lanting, Anna L. Brindley : The destroyed hunebed O2 and the adjacent TRB flat cemetery at Mander (Gem. Tubbergen, province Overijssel). In: Palaeohistoria. Volume 45/46, 2003/2004 (2004), pp. 59-94 ( online ).

- W. Meeüsen: Het verdwenen hunebed D54a bij Spier, according to Beilen. Dissertation, Groningen 1983.

- J. Molema: Het verdwenen hunebed D43a op de Emmer Es te Emmen. Dissertation, Groningen 1987.

- Jan Willem Okken : De Verhinderde verkoop van hunebedden te Rolde, 1847-1848. In: Nieuwe Drentse Volksalmanak. Volume 106, 1989, pp. 74-86.

- Daan Raemaekers , Sander Jansen : A paper opgraving van hunebed D12 Eexteres. Van ganggraf naar dolmen. In: Paleo-aktueel. Volume 24, 2013, pp. 43-50 ( online ).

- Wijnand van der Sanden : Reuzenstenen op de es. De Hunebedden van Rolde. Waanders, Zwolle 2007, ISBN 978-90-400-8367-9 .

- Wijnand van der Sanden: Een hunebed in een park - Een bijdrage tot de biography van het grote hunebed van Borger. In: Waardeel. Volume 31 (1), 2011, pp. 1-5 ( online ).

- CW Staal-Lugten: The decorated TRB ceramics of the Hünenbett D19 in Drouwen, Prov. Drenthe. In: Analecta Praehistorica Leidensia. Volume 9, pp. 19-37 ( online ).

- Ernst Taayke : Drie vernielde hunebedden in de gemeente Odoorn. In: Nieuwe Drentsche Volksalmanak. Vol. 102, 1985, pp. 125-144.

- Adrie Ufkes : De inventarisatie van Hunebed O2 van Mander. Dissertation, Groningen 1992.

- Adrie Ufkes: Trechterbekeraardewerk uit het hunebed D52 te Diever, gemeente Westerveld (Dr.). Een Beschrijving van een particuliere collectie (= ARC reports. Volume 2007-20). ARC, Groningen 2007 ISSN 1574-6887 ( online ).

Special studies

- Wout Arentzen : WJ de Wilde (1860-1936). A forgotten onderzoeker van de Nederlandse hunebedden. Sidestone Press, Leiden 2010, ISBN 978-9088900600 ( online ).

- Jan Albert Bakker: July 1878: Lukis and Dryden in Drente. In: The Antiquaries Journal. Volume 54/1, 1979, pp. 9-18.

- Jan Albert Bakker: Protection, acquisition, restoration and maintenance of the Dutch hunebeds since 1734. An active and often exemplary policy in Drenthe (I). In: Reports van de Rijksdienst voor het Oudheidkundig Bodemonderzoek. Volume 29, 1979, pp. 143-183 ( online ).

- Jan Albert Bakker: De opgraving in het Grote Hunebed te Borger door Titia Brongersma op June 11, 1685. In: Nieuwe Drentse Volksalmanak. Volume 101, 1984, pp. 103-116.

- Jan Albert Bakker: Petrus en Adriaan Camper en de hunebedden. In: J. Schuller tot Peursum-Meijer, Willem Roelf Henderikus Koops (ed.): Petrus Camper (1722 - 1789). Onderzoeker van nature. Universiteitsmuseum, Groningen 1989, ISBN 90-367-0153-8 , pp. 189-198.

- Jan Albert Bakker: Prehistory Visualized: Hunebedden on Dutch School Pictures as a Reflection of Contemporary Research and Society. In: Reports van de Rijksdienst voor het Oudheidkundig Bodemonderzoek. Volume 40, 1992, pp. 29-71 ( online ).

- Jan Albert Bakker: Chronicle of megalith research in the Netherlands, 1547-1900: from Giants and a Devil's Cunt to accurate recording. In: Magdalena Midgley (Ed.): Antiquarians at the Megaliths (= BAR International series. Volume 1956). Archaeopress, Oxford 2009, ISBN 978-1-4073-0439-7 , pp. 7-22.

- Jan Albert Bakker, Willy Groenman-van Waateringe: Megaliths, soils and vegetation on the Drenthe Plateau. In: Willy Groenman-van Waateringe, M. Robinson (Ed.): Man-made Soils (= Symposia of the Association for Environmental Archeology. Volume 6 = BAR International Series. Volume 410). BAR, Oxford 1988, ISBN 0-86054-529-6 , pp. 143-181.

- Anna L. Brindley: The typochronology of TRB West Group pottery. In: Palaeohistoria. Volume 28, 1986, pp. 93-132 ( online ).

- Anna L. Brindley: The use of pottery in dutch hunebedden. In: Alex Gibson (Ed.): Prehistoric Pottery: People pattern and purpose (= British Archaeological Reports. Volume 1156). Archaeopress, Oxford 2003, ISBN 1-84171-526-3 , pp. 43-51 ( online ).

- A. César Gonzalez-Garcia , Lourdes Costa-Ferrer : Orientations of the Dutch Hunebedden. In: Journal for the History of Astronomy. Volume 34/2, No. 115, 2003, pp. 219-226 ( online ).

- Rainer Kossian : Non-megalithic grave systems of the funnel cup culture in Germany and the Netherlands (= publications of the State Office for Monument Preservation and Archeology Saxony-Anhalt - State Museum for Prehistory. Volume 58). 2 volumes. State Office for Monument Preservation and Archeology Saxony-Anhalt - State Museum for Prehistory, Halle (Saale) 2005, ISBN 3-910010-84-9 .

- Mette van de Merwe : A zoektocht naar cup marks op de Nederlandse hunebedden. Saxion Hogeschool, Deventer 2019 ( PDF; 20.4 MB ).

- Jan Willem Okken: Mr. L. Oldenhuis Gratama en het behoud van de hunebedden. In: Nieuwe Drentse Volksalmanak. Volume 107, 1990, pp. 66-95.

- Wijnand van der Sanden: In het spoor van Lukis en Dryden. Twee Engelse oudheidkundigen tekenen Drentse hunebedden in 1878. Matrijs, Utrecht 2015, ISBN 978-90-5345-471-8 .

- Elisabeth Schlicht : Copper jewelry from megalithic graves in Northwest Germany. In: News from Lower Saxony's prehistory. Volume 42, 1973, pp. 13-52 ( online ).

- Nynke de Vries : Excavating the Elite? Social stratification based on cremated remains in the Dutch hunebedden. Master thesis, Groningen 2015 ( online ).

Movies

- Alun Harvey: Dutch Dolmens. Hunebedcentrum, Borger 2021. In: YouTube . April 23, 2021, accessed May 20, 2021.

Web links

- The Megalithic Portal: Netherlands (english)

- Hunebedden in Nederland (Dutch)

- De hunebedden in Drenthe en Groningen (Dutch)

- Het Hunebed Nieuwscafé (Dutch)

- Hunebeddenwijzer (Dutch)

- JohnKuipers.ca: A Hunebed Map of Drenthe (English)

- cruptorix.nl: De hunebedden in Nederland (netherlands)

- Website of the "Hunebedcentrum" in Borger (Dutch)

- De Hunebedden in Nederland - 3D-Atlas (Dutch)

Individual evidence

- ^ Anna L. Brindley : The typochronology of TRB West Group pottery. In: Palaeohistoria. Volume 28, 1986, pp. 93-132 ( online ). Annual figures corrected according to Moritz Mennenga : Between Elbe and Ems. The settlements of the funnel cup culture in northwest Germany (= early monumentality and social differentiation. Volume 13). Habelt, Bonn 2017, ISBN 978-3-7749-4118-2 , p. 93 ( online ).

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, pp. 36-38.

- ↑ Johan Picard: Korte Beschryvinge Van eenige Vergetene en Hidden Antiquities of the Provintien en Landen Located in Noord-Zee, de Yssel, Emse en Lippe. Goedesbergh, Amsterdam 1660.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, pp. 41, 44-48.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, pp. 49-50.

- ↑ Simon van Leeuwen: Batavia Illustrata, Ofte Verhandelinge vanden Oorspronk, Voortgank, Zeden, Eere, Staat en Godtsdienst van Oud Batavien, Mitsgarders Van den Adel en Regeringe van Hollandt / Ten deele uyt W. Van Gouthoven, en other Schryvers, maar wel voornamentlijk uyt een number of oude writings en Authentijque Stukken en Bewijsen, Te samen gesteldt by de Heer Simon van Leeuwen, In sijn leven Substituyt Griffier vanden Hogen Rade van Hollandt, Zeelandt, en Westvrieslandt. Veely, 's-Gravenhage 1685.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, pp. 51-52.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, pp. 54-56.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, pp. 59-60.

- ^ Petrus Speckman van der Scheer: In: Kronijk van het Historisch Gezelschap te Utrecht. Volume 4, 1848, pp. 190-192 ( online ).

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, pp. 57, 59.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, pp. 60, 62-63.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, pp. 64-66.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, pp. 67-69.

- ↑ Joannes van Lier: Oudheidkundige Brieven, bevattende eene negotiating over de manier van Anbaven, en over de Lykbusschen, Wagenen, Veld- en Eertekens of the Oude Germanen. van Thol, 's Gravenhage 1760.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, pp. 72-73.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, p. 91.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, p. 100.

- ↑ Engelbertus Matthias Engelberts: De Aloude State En Geschiedenissen Der Vereenigde Nederlanden. Deel 3rd Allart, Amsterdam 1790.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, pp. 100, 103.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, p. 63.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, pp. 103-104.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, pp. 105-108.

- ↑ Nicolaus Westendorp: Negotiating the answer to the question: welke volkeren hebben de zoogenoemde Hunebedden sticht? in wilted tijden men can be placed, dat zij deze oorden hebben bewoond. Oomkens, Groningen 1822.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, pp. 108, 110, 112-115.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, p. 118.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, pp. 120-121.

- ^ Johannes Pieter Arend: Algemeene Geschiedenis des Vaderlands van den vroegste tijden tot op heden. Deel 1: Van de vroegste tijden tot op het jaar 900 u. Chr. Schleijer, Amsterdam 1841.

- ↑ Grozewinus Acker Stratingh: Aloude state en geschiedenis des vaderlands. 2 (1): De bewoners. Vóór en onder de Romeinen. Schierbeek, Groningen 1849.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, p. 121.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, pp. 122-123, 125-126.

- ^ Leonhardt Johannes Friedrich Janssen: Drenthsche oudheden. Kemink, Utrecht 1848.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, p. 130.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, p. 133.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, pp. 134-138.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, pp. 138-141.

- ↑ Willem Hofdijk: Ons voorgeslacht in zijn leven dagelyksch geschilderd. Kruseman, Haarlem 1859.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, pp. 141-142.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, pp. 145-148.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, pp. 149-150, 153, 157-158.

- ^ Willem Pleyte: Nederlandsche Oudheden van de vroegste tijden tot op Karel den Groote. Leiden 1877-1902.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, pp. 160-162.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, pp. 163-165.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, pp. 181-182.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, pp. 173-174.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: The Dutch Hunebedden. Megalithic Tombs of the Funnel Beaker Culture. 1992, p. 6.

- ^ A b Jan Albert Bakker: The Dutch Hunebedden. Megalithic Tombs of the Funnel Beaker Culture. 1992, pp. 6-7.

- ↑ D53 and D54 / Havelte. In: hunebeddeninfo.nl. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, p. 22.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: The Dutch Hunebedden. Megalithic Tombs of the Funnel Beaker Culture. 1992, p. 7.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: De Westgroep van de Trechterbekercultuur. Studies over chronologie en geografie van de makers van hunebedden en diepsteekceramiek, ten Westen van de Elbe. Dissertation, Universiteit van Amsterdam, Amsterdam 1973, published as Jan Albert Bakker: The TRB West Group. Studies in the Chronology and Geography of the Makers of Hunebeds and Tiefstich Pottery (= Cingula. Volume 5). Universiteit van Amsterdam, Amsterdam 1979, ISBN 978-90-70319-05-2

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: The Dutch Hunebedden. Megalithic Tombs of the Funnel Beaker Culture. (= International Monographs in Prehistory. Archaeological Series. Volume 2). International Monographs in Prehistory, Ann Arbor 1992, ISBN 1-87962-102-9 .

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. From 'Giant's Beds' and 'Pillars of Hercules' to accurate investigations , Sidestone Press, Leiden 2010, ISBN 9789088900341 .

- ^ Anna L. Brindley: The typochronology of TRB West Group pottery. In: Palaeohistoria. Volume 28, 1986, pp. 93-132 ( online ).

- ^ Nynke de Vries: Excavating the Elite? Social stratification based on cremated remains in the Dutch hunebedden. 2015, p. 3.

- ↑ De Hunebedden in Nederland - A 3D model collection by the Groningen Institute of Archealogy. In: sketchfab.com. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: A list of the extant and formerly present hunebedden in the Netherlands. 1988, pp. 65-68.

- ↑ Bert Huiskes: Van veldnaam tot vindplaats? An onderzoek naar het association tussen hunebedden en 'steennamen' in Drenthe. In: Driemaandeljkse Bladen. Orgaan van het Nedersaksisch Instituut der Rljksuniversiteit te Groningen. Volume 37, 1985, pp. 81-94.

- ↑ Bert Huiskes: Steen names en hunebedden. Raakvlak van naamkunde en prehistorie (= Dutch archeological reports. Volume 10). Rijksdienst voor het Oudheidkundig Bodemonderzoek, Amersfoort 1990 ( online ).

- ^ Johannes Müller et al .: Periodization of the funnel cup societies. A working draft. In: Martin Hinz , Johannes Müller (eds.): Settlement, trench works, large stone grave. Studies on the society, economy and environment of the funnel cup groups in northern Central Europe (= early monumentality and social differentiation. Volume 2). Rudolf Habelt Verlag, Bonn 2012, ISBN 978-3774938137 , p. 30 ( online ).

- ^ A b Johannes Müller: Boom and bust, hierarchy and balance: From landscape to social meaning - Megaliths and societies in Northern Central Europe. In: Johannes Müller, Martin Hinz , Maria Wunderlich (Eds.): Megaliths - Societies - Landscapes. Early Monumentality and Social Differentiation in Neolithic Europe. Proceedings of the international conference “Megaliths - Societies - Landscapes. Early Monumentality and Social Differentiation in Neolithic Europe "(16th – 20th June 2015) in Kiel (= Early Monumentality and Social Differentiation. Volume 18/1). Habelt, Bonn 2019, ISBN 978-3-7749-4213-4 , p. 34 ( online ).

- ↑ Johannes Müller: Large stone graves, trench works, long hills. Early monumental buildings in Central Europe (= archeology in Germany. Special issue 11). Theiss, Stuttgart 2017 ISBN 978-3-8062-3464-0 , p. 9 ( online ).

- ↑ this is carefully considered by Jan Albert Bakker: De Steen en het Rechthuis van Lage Vuursche. 2005, p. 229.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: Megalithic Research in the Netherlands, 1547-1911. 2010, p. 8.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: The Dutch Hunebedden. Megalithic Tombs of the Funnel Beaker Culture. 1992, p. 11.

- ^ A b c Jan Albert Bakker: The Dutch Hunebedden. Megalithic Tombs of the Funnel Beaker Culture. 1992, p. 12.

- ^ A. César Gonzalez-Garcia, Lourdes Costa-Ferrer: Orientations of the Dutch Hunebedden. 2003, pp. 223-225.

- ^ A b c Jan Albert Bakker: The Dutch Hunebedden. Megalithic Tombs of the Funnel Beaker Culture. 1992, p. 13.

- ^ D27 / Borger. In: hunebeddeninfo.nl. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ Albert Egges van Giffen: De Hunebedden in Nederland. Volume 1. 1925, p. 145.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: The Dutch Hunebedden. Megalithic Tombs of the Funnel Beaker Culture. 1992, p. 22.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: The Dutch Hunebedden. Megalithic Tombs of the Funnel Beaker Culture. 1992, p. 29.

- ^ Jan Hendrik Holwerda: Two giant rooms near Drouwen (Prov. Drente) in Holland. 1913, fig. 1.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: The Dutch Hunebedden. Megalithic Tombs of the Funnel Beaker Culture. 1992, p. 30.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: The Dutch Hunebedden. Megalithic Tombs of the Funnel Beaker Culture. 1992, p. 28.

- ^ Jan Hendrik Holwerda: Two giant rooms near Drouwen (Prov. Drente) in Holland. 1913, p. 439.

- ^ Nynke de Vries: Excavating the Elite? Social stratification based on cremated remains in the Dutch hunebedden. 2015, pp. 12–14, 58.

- ^ Nynke de Vries: Excavating the Elite? Social stratification based on cremated remains in the Dutch hunebedden. 2015, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Nynke de Vries: Excavating the Elite? Social stratification based on cremated remains in the Dutch hunebedden. 2015, pp. 14–16.

- ^ A b c d Jan Albert Bakker: The Dutch Hunebedden. Megalithic Tombs of the Funnel Beaker Culture. 1992, p. 57.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: The TRB West Group. Studies in the Chronology and Geography of the Makers of Hunebeds and Tiefstich Pottery. 1979, pp. 54-56, 177.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n vessel shapes. In: nonek.uni-kiel.de. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Jan Albert Bakker: The TRB West Group. Studies in the Chronology and Geography of the Makers of Hunebeds and Tiefstich Pottery. 1979, p. 177.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: The TRB West Group. Studies in the Chronology and Geography of the Makers of Hunebeds and Tiefstich Pottery. 1979, pp. 56, 177.

- ^ A b Jan Albert Bakker: The TRB West Group. Studies in the Chronology and Geography of the Makers of Hunebeds and Tiefstich Pottery. 1979, pp. 50, 177.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: The TRB West Group. Studies in the Chronology and Geography of the Makers of Hunebeds and Tiefstich Pottery. 1979, pp. 59-60, 177.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: The TRB West Group. Studies in the Chronology and Geography of the Makers of Hunebeds and Tiefstich Pottery. 1979, pp. 57, 177.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: The TRB West Group. Studies in the Chronology and Geography of the Makers of Hunebeds and Tiefstich Pottery. 1979, pp. 57-59, 177.

- ^ A b Jan Albert Bakker: The TRB West Group. Studies in the Chronology and Geography of the Makers of Hunebeds and Tiefstich Pottery. 1979, p. 60.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: The TRB West Group. Studies in the Chronology and Geography of the Makers of Hunebeds and Tiefstich Pottery. 1979, p. 110.

- ^ Nynke de Vries: Excavating the Elite? Social stratification based on cremated remains in the Dutch hunebedden. 2015, pp. 16-18.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: The Dutch Hunebedden. Megalithic Tombs of the Funnel Beaker Culture. 1992, p. 58.

- ↑ Heinz Knöll: The north-west German deep engraving ceramics and their position in the north and central European Neolithic (= publications of the antiquity commission for Westphalia. Volume 3). Aschendorff, Münster 1959.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: The TRB West Group. Studies in the Chronology and Geography of the Makers of Hunebeds and Tiefstich Pottery. 1979.

- ↑ Anna L. Brindley: Pottery and large stone graves. Aardewerk en megalithic graves. In: Jan F. Kegler, Annet Nieuwhof (Red.): Land of Discoveries. The archeology of the Frisian coastal area. Ostfriesische Landschaftliche Verlags- und Vertriebsgesellschaft, Aurich 2013, ISBN 978-3-940601-16-2 , pp. 137-144.

- ^ Moritz Mennenga : Between Elbe and Ems. The settlements of the funnel cup culture in northwest Germany (= early monumentality and social differentiation. Volume 13). Habelt, Bonn 2017, ISBN 978-3-7749-4118-2 , p. 93 ( online ).

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: The Dutch Hunebedden. Megalithic Tombs of the Funnel Beaker Culture. 1992, pp. 62, 144.

- ^ Anna L. Brindley: The use of pottery in dutch hunebedden. 2003, p. 44.

- ^ Jan Albert Bakker: The Dutch Hunebedden. Megalithic Tombs of the Funnel Beaker Culture. 1992, pp. 58-59.

- ^ Mette van de Merwe: Een zoektocht naar cup marks op de Nederlandse hunebedden. 2019, pp. 2–3.