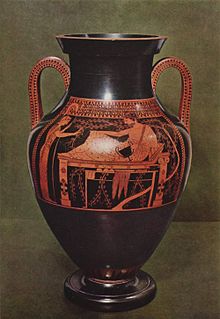

Amphora

An amphora or amphora (from ancient Greek ἀμφορεύς amphoreus 'two-handled clay vessel'; formed from ἀμφί amphí 'on both sides' and φέρειν phérein 'carry') is a bulbous, narrow-necked vessel with two handles, mostly made of clay, but also of metal (bronze, silver , Gold). Originally, two handles were supposed to make it easier to carry. Amphorae are among the ancient vases .

An amphora is any pottery that has two handles and whose base, which often consists of a point or a button, makes it difficult or impossible to hold it upright.

The amphora is also a unit of measurement . The volume as a Roman measure of capacity is one Roman cubic foot, which is about 26.026 l .

use

Amphorae were used in ancient times as storage and transport vessels for oil , olives and wine as well as for honey , milk , grain , garum , tropical fruits such as dates and others. They were produced in those regions in which the goods to be transported were produced, for example where wine or olive cultivation took place. Depending on the content, the volume is different, capacities are between 5 and 50 liters.

Often they were thrown away as one-way containers after transport, so the Monte Testaccio in Rome consists largely of amphorae fragments. Other specimens found a new use, for example as an urn in cremation burials or to cover the dead in body graves .

Today amphorae are only made for decorative purposes, for example as a vase . The amphora still plays a special role in the production of special wines, the so-called "amphora wine". This expansion is particularly popular with "biodynamic wines", but sulphurized wines from Georgia are also often expanded in special amphorae. See also: Quevri wine .

Archaeological importance

A change in shape and frequent inscriptions offer dating options. Absolutely datable finds from shipwrecks and other closed finds allow a chronological classification. The chronology of the pre-Roman Iron Age of Central Europe also includes the amphorae chronology .

As the origin and content of many amphorae forms are known, archaeological finds also allow the reconstruction of trade connections . Numerous amphorae also have amphorae stamps.

Greek amphorae

Types

There are different types of amphorae that were in use at different times. Some had a lid. The following types are examples of fine ceramics of the archaic and classical times. Certain types can also be found in Toreutic.

Neck amphora (approx. 6th – 5th century BC)

In the neck amphora, the handles are attached to the neck, which is separated from the stomach by a clear kink. There are two different types of neck amphora:

- the Nolan amphora (end of the 5th century), which is named after the place where Nola was found near Naples, and

- the Tyrrhenian amphora .

Some special forms of the neck amphora have certain peculiarities:

- the pointed amphora , the lower end of which is pointed and partly button-like.

- the loutrophoros , which was used to store the water during the marriage and burial rituals.

Abdominal amphora (approx. 640-450 BC)

In contrast to the neck amphora, the abdominal amphora does not have a separate neck, rather the abdomen merges into the neck in a curve. From the middle of the 5th century it was hardly produced.

The pelike is a special form of the abdominal amphora that appeared towards the end of the 6th century. With her, the belly is offset downwards, so the largest diameter is in the lower area of the vase body. The low center of gravity and the wide base give these vessels a particularly stable stand.

Panathenaic price amphora

A special form are the Panathenaic price amphoras with black-figure painting , which were made for the Athenian Panathenaic Festival and - apparently for cultic reasons - retained the black-figure painting style for centuries after the 'invention' of the red-figure painting style.

Similar shapes

Similar to ancient amphorae are the Amphoriskos and the Pithos .

Roman amphorae

Display as spherical panorama

General

Roman amphorae were mainly used for the transport and storage of basic foodstuffs such as olive oil , wine, fish sauces , fruits and grain. The capacity was often around 25 to 26 liters, which explains why the term amphora has become an important unit of measure for liquids over time (26.2 liters). Large bulbous olive oil amphoras from the Baetica of the Dressel 20 type with a content of 70 l could sometimes also reach a total weight of 100 kg. Occasionally stamps have been affixed to these, although research is uncertain whether these were made by the amphorae pottery or by the producer of the olive oil. Like the painted or carved numbers and letters ( graffiti or tituli picti ), they are an important epigraphic source for economic history.

Until the 1960s, amphora stamps and shapes were the main focus. In the 1970s and 1980s, international discussion forums on amphora research, including typology and chronology, took place. Around 1990 the amphorae from Augst / Kaiseraugst were evaluated for the first time, which served as the basis for the processing of amphorae from Mainz.

Typological classification

As evidence of a past commercial and consumer good, the Roman amphorae represent important potential information carriers on the economic history of the Roman era and provide information about the consumer behavior of the population at that time. The amphorae went unnoticed for a long time. The amphorae, like the rest of the ceramics, are often classified according to shape, origin and also according to content, since their number and variety is too great to be determined according to shape or origin.

At the end of the 19th century, the German archaeologist Heinrich Dressel established the first typological classification of the amphorae known at the time. The types named by him bear his name, supplemented by a numerical designation that marks the type of amphora (see picture example “Dressel 1B”). In part, its classification is still used today as the basis for the designation of the various types of amphora: Wine amphorae, such as Dr. 1, Dr. 2-4, Dr. 5, and oil amphoras, such as Dr. 20 and Dr. 23, will continue to be named after him (Dr. = Dressel). Dressel's work arose, among other things, from studying Roman finds, including Monte Testaccio, one of the largest complexes of Roman amphorae finds, and was published in the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum due to the small inscriptions . Other Roman amphora types are named after researchers such as the Italian underwater archaeologist Nino Lamboglia or sites such as Augst .

Amphorae in the Museo Archeologico Eoliano in Lipari

Monte Testaccio in Rome

Original shop fittings from Herculaneum in Campania (79 AD)

Manufacturing and geographical classification

The containers were mostly produced where they were needed for filling goods and from where they could be transported to their sales areas and destinations in a convenient manner. From the shape and origin of the amphorae it is possible to determine the transported products and their trade routes.

The scientific investigations into the manufacture of the amphorae are used to determine the origin of the clay mixture and the firing temperature. First it is checked which and how many types of clay were used in the production and whether the vessels have a natural sedimentary structure, or whether additional leanings have been added to the clay mixture. Then the firing temperature is determined. Although the weak and overburn samples also exist, a normal fire temperature of approx. 950 ° C was aimed for for most of the Italian amphorae.

Content and use

Amphorae were mainly used as a means of transport, storage or as grave goods. But in antiquity they were mainly used to transport certain foods, so to speak as the containers of antiquity. The amphorae were filled with various goods in the south and were specially traded in the north, where due to the different climate, corresponding products could not be grown and manufactured. The main trade routes via waterways were in the Mediterranean. Tall ships had space for up to 10,000 amphorae as they could be stacked several times. As a rule, the same product was filled into the same containers. There are only indications of unusual amphora contents in individual cases. The goods imported in the amphorae include, for example, olive oil from southern Adriatic Italy (Brindisi) and North Africa (Tripolitana I), pickled olives from Morocco (Schörgendorfer 558), wines from Catalonia, southern France, Italy (Dressel 2-4), Crete, Rhodes (Camulodunum 184) and North Africa, fish sauce from Upper Adriatic Italy (Dressel 6A) or figs and dates from Egypt and Syria.

Either the amphorae of one type dominate within a product group or there are amphorae of different shapes in more or less equal quantities. It is noteworthy that once they had fulfilled their function of transporting goods, they were not used in the same way a second time. They were either disposed of as garbage without further use or converted into coffins, urinals, building materials or even antique Molotov cocktails. They were attractive for re-use because of their mass availability. Almost 6,000 amphorae were found in Augst and Kaiseraugst, 5,000 in Mainz, 7,500 in the Mainz area, 1,500 each in the legion camp of Dangstetten and in Neuss. In addition to the written and image sources, the archaeological findings and finds provide information about their diverse areas of application. Some of the most famous examples of the rubble mounds or rubbish dumps, which consist of amphorae, would be the rubble mound of the legionary camp on the Kästrich in Mainz and the amphorae depot at Dimesser Ort and the Hopfengarten in Mainz.

Graffiti on amphorae in Mainz

Certain stamps called graffiti or marks ante cocturam are pressed into the as yet unfired amphorae . The Mainz amphorae have more than 200 scratches and marks. Only a few of them allow statements to be made about product labeling and product owners. Graffiti and brands ante cocturam are related to the production of containers and do not refer to the goods to be filled or to their future owner.

Numerous post cocturam scratches are so shortened or fragmented that an interpretation is not possible. The graffiti post cocturam mainly contain dimensions and name people or groups who are to be interpreted as possible product owners . The graffiti convey different information than the brush inscriptions.

Company signs such as trident, anchor, palmette or star provide additional information about the origin of the amphorae.

Distribution of the amphorae

Unlike the imported tableware, the amphorae are pure transport containers that are found in settlements, graves and shipwrecks and largely come from long-distance trade. Their geographical and sometimes wide spread corresponds to the distribution and sales of the content. Therefore, the delivery areas of these amphorae are shown in the distribution maps, not the production areas, which are only localized by the stamps or scientific investigations.

Analyzes of the remains of the contents determine the form, chronology, origin and imported goods (mostly Mediterranean foods). This applies in particular to the amphorae of the early and middle Imperial Era, while in late antiquity the relationship between form and content is not always clear.

With a few exceptions, the mapped sites are settlement finds, i.e. amphorae that were emptied and finally thrown away as part of settlement activities and that have become known from literature and through autopsy. However, the distribution of the amphorae reflects - as always with archaeological maps - the state of research. Distribution maps of amphorae have so far mainly been available for the Mediterranean region. The distribution and thus the questions of sales areas and trade routes in the provinces north of the Alps have not been dealt with very much.

The shapes of some early and mid-Imperial (7 late Roman) amphorae: 1) Dressel 1, 2) Gauloise 4, 3) Gauloise 5, 4) Camulodunum 184, 5) Crétoise 1, 6) Dressel 43, 7) Keay 25, 8) Dressel 6, 9) Dressel 20, 10) Dressel 10 similis / Lyonnaise 3, 11) Dressel 9 similis / Lyonnaise 3, 12) Augst 17 / Lyonnaise, 13) Schörgendorfer 558

High quality amphorae

In addition to the pointed amphorae used for trading, transport and storage of goods, there are occasionally higher quality amphorae, for example made of glass and metal. These amphorae usually have one foot. The shape of the amphora was only rarely taken up in Roman times, sometimes in the style of a pelike ; other forms of vessels (such as pitchers) are much more common.

The Portland vase with its cameo glass relief images was in the 18th and 19th centuries. Century had a strong role model effect on the art of that time.

Glass amphora, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Portland Vase, British Museum

Replica of the Portland Vase in Wedgwood pottery , circa 1790, Victoria and Albert Museum

literature

- Roald Docter : Transport amphorae . In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 12/1, Metzler, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-476-01482-7 , Sp. 756-760.

- V. Degrassi, D. Gaddi, L. Mandruzatto: Amphorae and coarse ware from late Roman-early medieval layers of the recent excavations in Tergeste / Trieste (Italy). In: M. Bonifay, JC. Tréglia (Ed.): LRCW 2. Late Roman coarse wares, cooking wares, and amphorae in the Mediterranean. (= BAR International Series. 1662). Oxford 2007, ISBN 978-1-4073-0098-6 , pp. 503-510.

- U. Ehmig: Dangstetten IV. The amphorae. Investigations into the supply of a military installation in Augustan times and the basics of archaeological interpretation of finds and findings. State Office for Monument Preservation in the Stuttgart Regional Council. (= Research and reports on prehistory and early history in Baden-Württemberg. 117). Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8062-2394-1 .

- U. Ehmig: The Roman amphorae from Mainz. (= Frankfurt archaeological writings. Volume 4). Bibliopolis, Möhnesee 2003, ISBN 3-933925-50-9 .

- U. Ehmig: The Roman amphorae in the area around Mainz. (= Frankfurt archaeological writings. Volume 5). Wiesbaden 2007, ISBN 978-3-89500-567-1 .

- U. Ehmig: Garbage, Molotov, misunderstandings. Dealing with empty amphorae elsewhere and in Roman Mainz. In: S. Wolfram (Ed.): Müll. Facets from the Stone Age to the Yellow Sack. Accompanying brochure for the special exhibition from 06.06 to 30.11.2003 in Oldenburg, then in Hanau. (= Series of publications by the State Museum for Nature and Man. Volume 27). 2003, ISBN 3-8053-3284-X , pp. 75-85.

- U. Ehmig: Scientific investigations on Roman amphorae from Mainz and their cultural-historical interpretation. In: N. Hanel, M. Frey (Ed.): Archeology, natural sciences, environment. Contributions of the working group "Roman Archeology" at the 3rd German Archaeological Congress in Heidelberg, May 25-30, 1999. (= BAR International Series. Volume 929). Oxford 2001, ISBN 1-84171-223-X , pp. 85-100.

- Norbert Hanel : Heavy ceramics. In: Thomas Fischer (Ed.): The Roman Provinces. An introduction to their archeology. Theiss-Verlag, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-8062-1591-X , p. 300f.

- Stefanie Martin-Kilcher : The Roman amphorae from Augst and Kaiseraugst. A contribution to Roman trade and cultural history. (= Research in August 7, 1-3). Römermuseum Augst, 1987–1994, DNB 551301686 .

- Stefanie Martin-Kilcher: Distribution maps of Roman amphorae and sales areas for imported food. In: Munster contributions to ancient trading history. Volume 13, No. 2, 1994, pp. 95-121.

- Stefanie Martin-Kilcher: Amphorae: Archaeological questions and questions. In: Excavation - Research - Presentation (= Xanten reports. Volume 14). Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2006, pp. 11-18.

- Ingeborg Scheibler : Amphora 1. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 1, Metzler, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-476-01471-1 , column 625 f.

- F. Schimmer: Amphorae from Cambodunum / Kempten. A contribution to the trading history of the Roman province of Raetia. (= Munich contributions to Roman provincial archeology. Volume 1; = Cambodunumforschungen. Volume VII). Wiesbaden 2009, ISBN 978-3-89500-659-3 .

- W. Schultheis (Ed.): Amphorae. Determination and introduction according to their characteristics. Bonn 1982, ISBN 3-7749-1913-5 .

- G. Thierrin-Michael: Roman wine amphorae. Mineralogical and chemical investigations to clarify their origin and production method. Dissertation . University of Freiburg 1990, DNB 94009648X .

- Stephan Weiß-König: Graffiti on Roman pottery from the area of Colonia Ulpia Traiana, Xanten. (= Xantener reports , Volume 17). Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2010, ISBN 978-3-8053-4273-5 .

Web links

- Publications for the search term amphora in the catalog of the German National Library

- Search for amphorae in the German Digital Library

- Bulletin amphorologique

Individual evidence

- ^ Wilhelm Gemoll : Greek-German school and hand dictionary . G. Freytag Verlag / Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky, Munich / Vienna 1965. S.?

- ↑ W. Schultheis (Ed.): Amphoren. Determination and introduction according to their characteristics . Bonn 1982, p. 13 .

- ^ Brendan P. Foley et al .: Aspects of ancient Greek trade re-evaluated with amphora DNA evidence. In: Journal of Archaeological Science. 39, 2012, pp. 389-398 ( abstract ); sciencemag.org ( memento of November 17, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) of October 13, 2011: "Will DNA Swabs Launch CSI: Cargo Scene Investigation?"

- ↑ Norbert Hanel : Heavy ceramics. In: Thomas Fischer (Ed.): The Roman Provinces. An introduction to their archeology. Theiss, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-8062-1591-X , p. 300f.

- ↑ G. Thierrin-Michael: Dissertation: Römische Weinamphoren. Mineralogical and chemical investigations to clarify their origin and production method . Freiburg 1990, p. 17 .

- ^ Heinrich Dressel (Ed.): Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum. Volume 15: Inscriptiones urbis Romae Latinae. Instrumentum domesticum. Reimer, Berlin 1891–1899.

- ↑ a b U. Ehmig: The Roman amphorae from Mainz (= Frankfurt archaeological writings . Volume 4 ). Bibliopolis, Möhnesee 2003, ISBN 3-933925-50-9 , p. 72-77 .

- ↑ a b S. Martin-Kilcher: Distribution maps of Roman amphorae and sales areas for imported food . In: Munster contributions to ancient trading history . tape 13 , no. 2 , 1994, p. 96 .