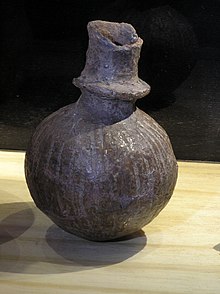

Collar bottle

The collar bottle ( Danish Dysseflaske or Kraveflaske ; Swedish more precisely called Kraghalsflaska ) is typical for the later time horizon of the funnel beaker culture (TBK - 3500–2800 BC). One speaks of a collar bottle horizon. Jażdżewski (1908–1985) already pointed out, however, that the circulation time of the collar bottle is shorter than that of the funnel beaker. Collar bottles occur in settlements and graves. Individual thick-walled, coarse and undecorated bottles have been found in Danish moors .

distribution

The center of distribution is in the western Baltic Sea region , on the Danish islands and in the Weser - Ems region . According to Knöll, the collar bottles disdain the North Sea coast and the tidal area of the Vlaardingen culture in the Rhine estuary . Collar bottles can be found in the following cultures and regions:

- TBK: ( Netherlands , Germany , Poland , Denmark - ceramic B group), Sweden (in Slutarpsdösen )

- Wartberg culture

- Brittany (six pieces)

- in Normandy one specimen was found in a megalithic tomb on the Channel coast .

- Collar bottles are common in Lesser Poland . In the Książnice Wielkie settlement in the Pińczów District , beakers and flasks were the most common ceramic shapes.

shape

Small, spherical, bottle-like, often thin-walled vessel with a flat bottom, a narrow neck and a ring-like ruff. The height is between 8 and 12 cm. The bulbous body can be round or double-conical in shape, possibly also divided by a shoulder break. The narrow neck is interrupted approximately in the middle of its length by a ring that was attached from the outside or pushed out of the neck from the inside. This “collar” gave the vessel its name. The model for the collar bottles could be previously stiffened animal bladder containers implemented in clay , as sometimes made clear by ribs or incised lines on the round body. The belly is often decorated with lines, fringes, dots, crosses, ladder tapes or imprints of cord. The projection can also be patterned, and marginal notches can also be found on the vessel. In the southeast of the distribution area, marginal groups of this species also adorn themselves with handles or feet. A collar bottle with a double spout was found in the Tannenhausen large stone grave in East Friesland . Collar bottles are made up of annular beads.

use

Collar bottles, together with one-handled jugs and amphorae, are part of the typical funeral ceramics of the funnel cup culture. These grave vessels are often made very carelessly, asymmetrical, little or no skimmed and badly fired.

A collar bottle filled with sulfur from the Gellenerdeich settlement ( Oldenburg , Lower Saxony ) indicates its use as a medicine bottle . The formerly liquid contents of other collar bottles consisted of vegetable oils. When closed with a stopper, the collar bottles could be used to store precious liquids.

Dolmens and earth graves with individual burials usually contained only one collar bottle. Multiple-use graves can contain several collar bottles, e.g. For example, in Dötlingen in Oldenburg, the remains of 27 flask bottles were discovered in various backfill layers. Collar bottles (presumably filled) belonged to the grave inventory and are often the only surviving addition. An earth grave from Laschendorf, Malchow in the Mecklenburg Lake District , where the stool was on the left-hand side contrary to the general rule, contained a ribbed pipe, Schlag - and sound instruments, and a belemnite that was mostly cut.

genesis

Andrew Sherratt assumes that the collar bottle originated in Central Europe and spread to Denmark from there. Gordon Childe looked for the origin of the collar bottle in the Maikop culture or the Kurgan of Maikop , but later withdrew this view.

literature

- Jan Albert Bakker: The TRB West Group, Studies in the Chronology and Geography of the Makers of Hunebeds and Tiefstich Pottery. Amsterdam, Universiteit van Amsterdam 1979, ISBN 978-90-70319-05-2 .

- Heinz Knöll 1981: Collar bottles. Their distribution and their time in the European Neolithic. Offa books 41, Neumünster, Wachholtz Verlag.

Web links

- Lüneburg history - with a picture of a collar bottle

- Description Danish and picture

Individual evidence

- ↑ Konrad Jażdżewski, summarizing overview of the funnel cup culture. Prehistoric Journal 23, p. 78. ISSN 1613-0804

- ↑ Heinz Knöll, collar bottles, their distribution and their time in the European Neolithic. Offa books 41, Neumünster 1981, p. 11

- ↑ Jozef Zurowski, New Results from Neolithic Research in the Southwest Polish Loess Region. Prehistoric Journal 21, Issue 1–2, 13, ISSN (Online) 1613-0804, doi : 10.1515 / prhz.1930.21.1-2.3

- ↑ Konrad Jażdżewski, summarizing overview of the funnel cup culture. Prehistoric Journal 21, p. 86. doi : 10.1515 / prhz.1930.21.1-2.3

- ^ Robert BK Stevenson, Prehistoric Pot-Building in Europe. Man 53, 1953, 65. doi : 10.2307 / 2794346

- ↑ Tomasz J. Chmielewski, Cmentarzysko. Aranżacja przestrzeni grzebalnej i obrazadek pogrzebowy. In: Tomasz J. Chmielewski / Edmund Mitris (eds.), Pliszczyn, stanowisko 9. Eneolityczny kompleks osadniczy na Lubelszczyźnie . Ocalone dziedziczwo Archeologicne 5, Pękowice-Wroclaw 2015, p. 147. ISBN 978-83-940949-1-1

- ↑ Tomasz J. Chmielewski, Cmentarzysko. Aranżacja przestrzeni grzebalnej i obrazadek pogrzebowy. In: Tomasz J. Chmielewski / Edmund Mitris (eds.), Pliszczyn, stanowisko 9. Eneolityczny kompleks osadniczy na Lubelszczyźnie . Ocalone dziedziczwo Archeologicne 5, Pękowice-Wroclaw 2015, p. 148. ISBN 978-83-940949-1-1

- ↑ http://www.landesarchaeologen.de/fileadmin/Dokumente/Dokumente_Kommissions/Dokumente_Grabungstechniker/Grabungstechnikerhandbuch/11_2_Nord-_und_Mitteldeutschland_Version_1998.pdf , 11.2

- ^ Andrew Sherratt, The Genesis of Megaliths: Monumentality, Ethnicity and Social Complexity in Neolithic North-West Europe. World Archeology 22/2 (Monuments and the Monumental) 1990, 162. JSTOR 124873

- ^ V. Gordon Childe, The dawn of European civilization . London 1925, 232

- ^ V. Gordon Childe, The Forest Cultures of Northern Europe: A Study in Evolution and Diffusion. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 61, 1931, 340. JSTOR 2843923