Soul hole

Soul hole ( French dalle hublot ) is a name for an "entrance and exit opening for the soul of the deceased" after Abraham Lissauer . Heine-Geldern defines the term more narrowly as “... the opening made in the locking stones of so many megalithic graves .” For Otto Höver , megalithic graves were “massive spell-casings against the demonic power of the living corpse and at the same time seats for the souls who have been separated as a precaution small opening - the so-called soul hole - was left in the stone structure, where the anima could secretly slip in and out. ”The term was used in archeology and ethnology , but is considered out of date. The German word “Seelenloch” is also used in English-language publications.

Pierced stones

distribution

Soul holes in stones occur in Spain, Ireland, Italy, England (Channel Islands), France, Switzerland, Germany, Sweden, Russia and India.

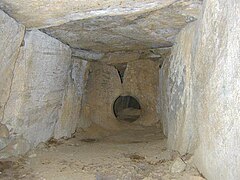

Gallery graves or stone boxes

The portal stones, especially of gallery graves or dolmens of the Schwörstadt type, are often perforated. Examples are the La Chaussée-Tirancourt gallery grave of the Seine-Oise-Marne culture in France or the Heidenstein from Niederschwörstadt , the remains of a Dolmen of the Schwörstadt type. Stone boxes of the Westphalian-Hessian type usually have perforated stones as access, e.g. B. the stone box near Altendorf (today Naumburg), Kassel district. The stone box on the Hartberg of Schankweiler contained a collar bottle , also belongs to the Wartberg horizon. A lock stone was found at the gallery grave of Guiry-en-Vexin .

- Soul holes

Soul hole in the stone box from Skogsbo or Norra-Säm (Sweden)

Alcaidús d'en Fàbregues soul hole ; Menorca

Soul hole in the stone chamber grave of Züschen , Hesse

Other Neolithic findings

Outside the distribution area of the gallery graves, round or oval soul holes can also be found on the Golan ( Ala-Safat ), in Sweden (called Gavelhål there ) in about 60 megalithic stone boxes in the west of southern Sweden, in Ireland in South Tyrol ( stone chamber grave from Gratsch ) and on Menorca (e.g. the Dolmen de Binidalinet , Dolmen de Montplé , Alcaidús d'en Fàbregues and Ses Roques Llises ). The Swedish stone boxes with a soul hole are mostly found in the interior of Västergötland. There is a smaller group in Bohuslän and on Göta älv . The Bostrup box, which is widespread in North Jutland and is close to the Swedish forms, also occurs here.

Some openings are rectangular or semicircular.

Metal Age finds

Stone boxes with perforated stone are typical of the early Bronze Age stone boxes of the Maykop culture in southern Russia and in the Caucasus , for example in the Klady burial ground . Occasionally, Urnfield steles or slabs with holes have also been found (e.g. the grave slab of Illmitz , HaA 2 in the Natural History Museum in Vienna ).

Hole stones ("porthole slabs") are common in the basement of medieval Ireland .

In Melanesia , soul holes have also been identified in dolmens used to bury skulls.

Openings in urns

An opening made in an urn after the fire is sometimes called a soul hole. The holes can be in the wall or in the bottom of the vessels. Pierced covers are documented in East and West Prussia. Soul holes are common in urns of the Lusatian culture and Urartean incendiary vessels.

Abraham Lissauer also found urns with holes in the cemetery of Dahnsdorf (Brandenburg) that had been made before the fire. The dolia , which served as grave covers ("bells"), were pierced after the fire, however, Lissauer observed that "on the inner floor surface a layer appears as if it had blown off". For Lissauer, however, it is inexplicable why not all dolia and urns are pierced. Buchholz was also able to find a conical bowl with a notched rim in the Lusatian grave field of Beelitz , a "drilled and smoothed hole" in the ground before the fire. Pastor Senf was able to prove in the urn grave field of Sproitz , today the district of Görlitz , that the perforation was carried out on site. He found ceramic remnants from the perforation 3 cm above the hole in the corpse fire and concluded: "Only after these [remains] were embedded in the vessel did it receive a traffic door." Mustard assumed that the drillings were made with a sharp stone.

In urns from Roman provincial burial grounds, intentional perforations of the soil are also known, which are known as soul holes.

Soul holes in coffins

The hand-made anthropomorphic clay coffins from Deir el-Balaḥ in Israel are heavily influenced by Egypt, but were made on site. Some of them have holes in the bottom, on the back, but also near the head. These are interpreted as soul holes, but also as drains for putrefactive juices. During the funeral ceremony in Taiwan , a Feng Shui specialist punched a hole in the hardwood coffin with a hammer and chisel so that the mana of the deceased could escape. To keep the hole clear after the coffin was sunk, it was protected with five stones.

Graves

Even in stone tombs in classical Greece and in Lycia there are sometimes small openings near the gable. FJ Tritsch also sees these as soul holes, but would like to call them false doors . Classical tombs in Cyprus sometimes have a door stone with a hole (e.g. Marion tomb 6A with a seated burial), which Gjerstad et al. however, to be interpreted as an opening for the offering of dead donations , not as a soul hole. This may also apply to other, comparable findings.

Heintze describes stone mounds in the necropolises of Zonguege, Quibanda and Massa Dois in Angola , which have openings intentionally left free and bordered with stones. She interprets these as soul holes or sacrificial windows.

Further occurrence of soul holes

- Swiss wooden houses sometimes have a "soul hole" (also "poor soul hole") through which the soul of the deceased can get outside, which Otto Tschumi considers a very old custom.

- In Tibet it is believed that the souls of the dead have to pass through a narrow "soul hole" (in a stone) before they can get before the judge of the dead, Yama or Tsi'u . Hummel depicts such a soul hole from the monastery bSam-yas .

- In Maya graves there are often (partly broken) ceramic vessels with a small hole in the middle. This serves the cultic-ritual rendering useless and is also referred to as a "soul hole".

Research history

In terms of research history, the term soul hole is associated with that of the “ megalithic culture ”. Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf assumed a connection between the South Indian megaliths on the one hand and the West Asian and Mediterranean megaliths on the other, because all three sometimes had soul holes. Heine-Geldern assumed that dolmens with a soul hole spread over the Mediterranean region, Palestine, the Caucasus and Persia ( Tepe Sialk ) as far as the Deccan and southern India.

interpretation

The term soul hole goes back to a Scandinavian popular belief. It is based on the idea that the hole was created to allow the soul or spirit of the deceased to leave the tomb. This idea also seems to be represented in Greek popular belief. FJ Tritsch reports of a shepherd on Mount Euboia who explained the lack of a soul hole above the entrance to the so-called Tholos of the tantalid Aigisthus by saying that the murderer and adulterer's soul was to be kept in the grave.

Heine-Geldern considers a “doctrine of salvation and redemption or, if you want to put it more soberly, a magical technique new for its time to overcome the dangers of death threatening the soul, combined with new rites and, at least as far as Southeast Asia is concerned, likely with a new sacrificial animal, the cattle ”for the basis of megalithic buildings as a whole. and believes in a great religious movement, perhaps spread by missionaries. Philippson sees the soul holes in megaliths as evidence of animistic ideas. José Miguel de Barandiarán saw the soul holes of the Eeolithic Basque megalithic complexes as evidence of a belief in life after death, while the east-west orientation of the graves indicates a cult of the sun.

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ Abraham Lissauer: The burial ground on Haideberg near Dahnsdorf, Zauche-Belzig district and “bell-shaped” graves in particular. Extraordinary meeting of January 26, 1895, Zeitschrift für Ethnologie 27, 1895, 97

- ↑ Robert Heine-Geldern: The megaliths of Southeast Asia and their significance for the clarification of the megalithic question in Europe and Polynesia. Anthropos 23 / 1–2, 1928, p. 276

- ↑ Otto Höver: Bookkeeping and Balance Sheet of World History in a New View: On Arnold J. Toynbee's interpretation of early human events . In: Zeitschrift für Religions- und Geistesgeschichte 2/3, 1949/50, p. 254. JSTOR 23894388 , accessed on November 4, 2015.

- ↑ z. BM Gaffikin: Preliminary Report on Pottery from Ballintoy Caves, Co. Antrim. The Irish Naturalists' Journal 5/5, 1934, p. 112.

- ↑ Gustav Perret: Cro-Magnon types from the Neolithic until today (a contribution to the racial history of Lower Hesse). In: Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie 37/1, 1937, 5-7.

- ↑ Reinhard Schindler : Stone box with a soul hole and Iron Age settlement in Schankweiler, district of Bitburg. In: Trier Zeitschrift 30, 1976, pp. 41-61; Niels Bantelmann : The Neolithic finds from the Eyersheimer mill in the Palatinate. In: Prehistoric Journal 59/1, p. 34f.

- ↑ http://www.cercle-sequana.fr/index.php?post/sortie-dans-le-Vexin-dimanche-24-juillet-2011 Guiry-en-Vexin

- ↑ Estyn E. Evans: Giants' Graves. In: Ulster Journal of Archeology , Third Series 1, 1938, p. 9.

- ^ Klaus Ebbesen: Nordjyske gravkister med indgang. Bøstrup cistern. In: Aarbøger for nordisk Oldkyndighed og Historie 1983, pp. 5-65.

- ↑ Alexej D. Rezepkin: The early Bronze Age burial ground of Klady and the Majkop culture in northwestern Caucasus . (Translated from the Russian by Ida Nagler). Archeology in Eurasia, 10. Leidorf, Rahden / Westfalen 2000, ISBN 3-89646259-8

- ↑ http://www.gemeinde-illmitz.at/marktgemeinde/geschichte/

- ↑ Mark Clinton: Porthole slabs in basements in Ireland. In: Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland 127, 1997, pp. 5-17. JSTOR 25549824

- ↑ Alphonse Riesenfeld : The Megalithic Culture of Melanesia. EJ Brill, Leiden 1950, p. 136.

- ↑ z. B. Tünde Kaszab-Olschewski : The villa rustica Hambach 516 in the Rhenish lignite mining area - graves and enclosure ditches. Master thesis. Bonn 2000, p. 173.

- ↑ Otto Tischler : Schriften der Physikalisch-Wirtschaftsgesellschaft, 27. p. 136, Conwentz in the report on the West Prussian Provincial Museum in Danzig for 1893, p. 30, quoted from Abraham Lissauer: Das Gräberfeld am Haideberg near Dahnsdorf, Kreis Zauche- Belzig and “bell-shaped” graves in particular. Extraordinary meeting of January 26, 1895, Zeitschrift für Ethnologie. 27, 1895, p. 114

- ↑ Abraham Lissauer: The burial ground on Haideberg near Dahnsdorf, Zauche-Belzig district and “bell-shaped” graves in particular. Extraordinary meeting of January 26, 1895, Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, 27, 1895, 114f.

- ↑ Zafer Derin: Potters' Marks of Ayanıs Citadel, Van. In: Anatolian Studies 49, 1999, 90

- ↑ a b Abraham Lissauer: The grave field on Haideberg near Dahnsdorf, district of Zauche-Belzig and "bell-shaped" graves in particular. Extraordinary meeting of January 26, 1895, Zeitschrift für Ethnologie 27, 1895, pp. 114–115

- ^ Buchholz: Prehistoric burial places and dwellings. Session of June 21, 1890, Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, 22, 1890, p. 371, fig. 14.

- ↑ Mustard: bronze needles with a conspicuous point, etc. In: Zeitschrift für Ethnologie 32, 1900, p. 387

- ^ Trude Dothan: Anthropoid Clay Coffins from a Late Bronze Age Cemetery near Deir el-Balaḥ (preliminary report 2). In: Israel Exploration Journal 23/3, 1973, p. 130

- ↑ Peter Thiele: Chinese funerary customs in northern Taiwan. In: Zeitschrift für Ethnologie 100, 1/2, 1975, p. 107. JSTOR 25841509 , accessed on November 4, 2015

- ^ FJ Tritsch, False Doors on Tombs. Journal of Hellenic Studies 63, 1943, pp. 113-115

- ^ Einar Gjerstad, John Lindros, Erik Sjöqvist, Alfred Westholm: The Swedish Cyprus Expedition, Finds and Results of the Excavations in Cyprus 1927-1931 , Volume 2. Stockholm 1935

- ↑ Beatrix Heintze : Burial in Angola - a synchronic-diachronic analysis. In: Paideuma: Mitteilungen zur Kulturkunde 17, 1971, p. 189 ( at JSTOR )

- ↑ Otto Tschumi: Review of: Hoffmann-Krayer , Eduard: Feste und customs of the Swiss people. Revised by Paul Geiger, Zurich, Atlantis-Verlag 1940. In: Anthropos , 35–36 / 4, 1940/1941, p. 1031

- ^ Siegbert Hummel: The funeral in Tibet. In: Monumenta Serica , 20, 1961, p. 273

- ↑ Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf: The Problem of Megalith Cultures in Middle India . Man in India 25/2, 1945, pp. 84f

- ↑ Robert Heine-Geldern: The Dravidaproblem. Gazette of the philosophical-historical class of the Austrian Academy of Science 9, 101/25, 1964, Vienna, 187-201.

- ↑ Ina Wunn: Götter, Mütter, Anhnenkult, Neolithic Religions in Anatolia, Greece and Germany , 1999, p. 151

- ↑ Olaf B. Rader: Grave and rule: political death cult from Alexander the great to Lenin . Munich, CH Beck 2003, ISBN 3406509177 , p. 32.

- ↑ Ditmar Brock: Life in Societies: From the origins to the ancient high cultures . Berlin, Springer 2006, ISBN 9783531149271 , p. 167.

- ↑ Haik Avetisian, Urartian Ceramics from the Ararat Valley as a cultural phenomenon a tentative representation. Iran and the Caucasus 3, 1999/2000, 302.

- ^ FJ Tritsch: False Doors on Tombs. Journal of Hellenic Studies 63, 1943, p. 114

- ↑ Robert Heine-Geldern, The megaliths of Southeast Asia and their significance for clarifying the megalithic issue in Europe and Polynesia. Anthropos 23 / 1–2, 1928, p. 314

- ↑ Robert Heine-Geldern: The megaliths of Southeast Asia and their significance for the clarification of the megalithic question in Europe and Polynesia. Anthropos 23 / 1–2, 1928, p. 315

- ^ Ernst A. Philippson: Review of: Friedrich Pfister, Deutsches Volkstum in Faith and Superstition. Berlin, Walter de Gruyter 1936. Monthly booklets for German teaching 29/5, 1937, p. 230. JSTOR 30169409

- ↑ José Miguel de Barandiarán: Huellas de artes y religiones antiguas en el Pirineo vasco. In: Homenaje al MJ Sr. Dr. D. Eduardo de Escarzaga , Vitoria 1935