devil

The devil is an independent and supernatural being in various religions . He plays a special role in Christianity and Islam as the personification of evil . In Christian art he is often depicted as a black-winged angel or as a “junker” with a horse's foot, in Islam a black figure symbolizes his corrupted nature. Mara or Devadatta takes the place of a "devilish" demon being in Buddhism .

Depending on the religion, cultural epoch and place, the devil is given different names.

Word origin

The word "devil" comes from the ancient Greek Διάβολος Diábolos, literally 'jumble' in the sense of 'confounder, twisting facts, slanderer' from διά dia ' throwing apart' and βάλλειν bállein 'throwing', put together to διαβάλλειν disguises ; Latin diabolus .

The devil in different religions

Judaism

In the translation of the Hebrew texts of Job 1 EU and Zechariah 3 EU into Greek , the Jewish ha-Satan became diabolos ('devil') of the Septuagint . The conceptions of Satan in Judaism are clearly different from the conceptions and the use of the term Satan in Christianity and Islam. Due to the interpretation and interpretation of the Tanach by the respective scholars, there are significant differences.

In the Tanakh, Satan is primarily the title of accuser at the divine court of justice (the Hebrew term Satan ( שטן, Sin - Teth - Nun ) means something like "accuser"). The term can also be used for people, the Hebrew word is then generally used without the definite article ( 1 Samuel 29.4 EU ; 1 Kings 5.18 EU ; 11.14.23.25 EU ; Psalm 109.6 EU ; as verbs in the sense of “enemy” or “hostility” in the Psalms: Ps 38,21 EU ; 71,13 EU ; 109 EU ). Usually the title Satan is bestowed on different angels and can then be indicative on its own.

In Judaism, Satan is not seen as something personified or even as evil personified. In Judaism, both good and bad are seen as two sides of a togetherness that both z. B. are based in God, the eternal being. Good and bad are of this world, which is transcendent to God, the eternal being. Satan, when the title is given to an angel in a context or in a story, does not always act on his own authority and not according to his own will, but on behalf of God and is fully under the control and will of God. The title of Satan is given to various angels and people in the Tanakh and other sacred writings of Judaism.

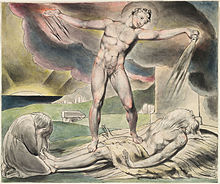

The most detailed account of an angel with the title Satan working on God's behalf can be found in the book of Job . The narrative begins with the scene at the heavenly court of justice where God and an angel are present. Because of the objection of the angel in this divine court, who acts as the accuser, i.e. as Satan , a reproach is made against God. The pious and prosperous Job is only faithful to God because God does not allow any misfortune around him. Then God allows Satan to test Job's trust in God. Despite the misfortunes and in spite of the painful illness that overtook the unsuspecting Job on behalf of God, Job accepted his sad fate and did not curse his God . However, he criticizes him and insists that he has done nothing wrong. Job's friends are convinced that he must have done wrong, because God does not allow an innocent man to suffer so much misfortune. This refutes the angel's objection that there is no human being who remains loyal to God in every situation or who does not apostate from God as soon as he is doing badly from a human point of view. In two other cases, a Satan appears as a tempter ( 1. Chronicles 21.1 EU ) or accuser ( Zechariah 3.1 EU ) of sinful man before God. In Num 22,22-32 EU the angel (Satan) who stands in the way is ultimately not acting negatively, but is sent by God to prevent worse for Balaam .

In the extra-biblical popular Jewish stories of the European Middle Ages, the title Satan is sometimes given to an angel who is cast out by God because he wanted to make himself equal to God. The stories in which this happens are told juxtaposed in full awareness and knowledge of the teachings of Judaism, which always rejected such ideas. He is considered to be the bearer of the principle of evil. Here alludes to old terms of the Persian culture, in which the dual principle of the fight between good and evil plays a major role, and the ideas of the surrounding Christian culture. They are therefore rather fantastic stories or horror stories and not biblical Jewish teachings or didactic Jewish tales of tradition. It is possible that the ideas of Christianity will only be retold by way of illustration in order to present the positions of Christians that contradict those of Judaism.

The Qliphoth of the Kabbalistic cosmology are metaphorically understood as veiling bowls of the “spark of divine emanation” and fulfill similar functions as the devil figures in other religious systems. In Judaism, divinity is understood with the revelation of the only reality of God, which, however, is veiled by the Qliphoth. Qliphoth are therefore associated with idolatry, impurity, evil spiritual forces such as Samael and the accusing satans , and sources of spiritual, religious impurity.

Christianity

In Christianity , the devil is the epitome of evil. He is also called (deviating from the Old Testament meaning of these names) Satan or Lucifer . The devil is seen as a fallen angel who rebelled against God .

The Christian tradition also often relates the serpent in the creation story to the devil. This equation can already be found in the Revelation of John . Traditionally, the devil is seen as the author of the lies and evil in the world. Revelation calls him the "great dragon, the old serpent called the devil or Satan and who deceives the whole world" ( Revelation 12.9 EU ). The letter to the Ephesians describes his work as "the rule of that spirit that rules in the air and is now still active in the disobedient". The devil is mentioned in detail in the apocryphal Ethiopian Book of Enoch as Azazel as one of those sons of God who with the daughters of man fathered the Nephilim , the "giants of ancient times".

Also in the New Testament, Satan is referred to as an angel who pretends to be the angel of light ( 2 Cor 11:14 EU ) and is presented as a personified spirit being who always acts as the devil. So it says: “He who commits sin is of the devil; for the devil sins from the beginning. But the Son of God appeared to destroy the works of the devil ”( 1 Jn 3 : 8 EU ).

In the book of Isaiah there is a song of mockery of the king of Babylon , a passage of which was later referred to by Christian tradition as Satan, but originally an allusion to the figure of Helel from the Babylonian religion , the counterpart to the Greek god Helios . The reference to the king is made clear at the beginning:

"Then you will sing this mocking song to the King of Babel: Oh, the oppressor came to an end, the need came to an end."

“Oh, you fell from heaven, you radiant son of the dawn. You fell to the ground, you conqueror of the peoples. But you thought in your heart: I will climb heaven; up there I set up my throne, over the stars of God; I sit on the mountain of the assembly of gods, in the far north. I rise far above the clouds to be like the highest. "

The church fathers saw in this a parallel to the fall of Satan described in Lk 10.18 EU ("He said to them: I saw Satan fall from heaven like lightning"). A theological justification for the equation is that the city of Babylon in Revelation will be destroyed by God together with the devil on the last day. Others object that an assumed simultaneous annihilation does not mean identity.

In a similar way, parts of Ez 28 EU were also related to the fall of Satan. There the prophet speaks of the end of the king of Tire, who, because of his pride, considers himself a god and is therefore accused. In verses 14–15 it is said to the king: “You were a perfectly formed seal, full of wisdom and perfect beauty. You have been in the garden of God, in Eden. All sorts of precious stones surrounded you […] Everything that was exalted and deepened in you was made of gold, all these ornaments were attached when you were created. I joined you with a fellow with outspread, protective wings. You were on the holy mountain of the gods. You walked between the fiery stones. "

In the Gospels , Jesus refers to the devil in various parables, for example in the parable of the weeds under the wheat:

“And Jesus told them another parable: The kingdom of heaven is like a man who sowed good seeds in his field. Now while the people were sleeping, his enemy came, sowed weeds under the wheat, and went away again. As the seeds sprouted and the ears formed, the weeds also came out. Then the servants went to the landlord and said, Lord, did you not sow good seeds in your field? Then where did the weeds come from? He replied: An enemy of mine did that. Then the servants said to him, Shall we go and tear it up? He replied: No, otherwise you will uproot the wheat together with the weeds. Let both grow until the harvest. Then, when the time of harvest comes, I will tell the workers: First gather the weeds and tie them in bundles to burn; but bring the wheat into my barn. "

Before the millennial kingdom , according to the revelation of John, there is a fight between the archangel Michael and his angels and Satan, which ends with the devil and his followers being thrown to earth (fall from hell). For the duration of the thousand-year empire, however, he was tied up, only to be briefly released afterwards. He then seduces people for a certain time before he is thrown into a lake of fire ( Rev. 20 : 1–11 EU ).

A few Christian communities, such as the Christadelphians , the Church of the Blessed Hope or Christian Science , reject the idea of the existence of a devil or Satan as a real evil spirit.

Roman Catholic Church

The denial of evil ( Abrenuntiatio diaboli ) belongs in the Roman Catholic Church to the rite of baptism and to the renewal of baptismal promises in the celebration of Easter vigil . In the Catechism of the Catholic Church in 391–394 it says about Satan:

“Scripture testifies to the disastrous influence of him whom Jesus calls the 'murderer from the beginning' (Jn 8:44) and who even tried to dissuade Jesus from his mission received from the Father [cf. Mt 4,1-11]. 'The Son of God appeared to destroy the works of the devil' (1 Jn 3: 8). The most disastrous of these works was the lying deception that led people to disobey God.

However, the power of Satan is not infinite. He is just a creature; powerful because he is pure spirit, but only a creature: he cannot prevent the building of the kingdom of God. Satan is active in the world out of hatred of God and of his kingdom, which is based on Jesus Christ. His actions bring terrible spiritual and even physical damage to every person and every society. And yet this his doing is permitted by divine providence, which directs the history of man and the world powerfully and mildly at the same time. It is a great mystery that God allows the devil to do something, but 'we know that God works everything to goodness with those who love him' (Rom 8:28). "

The Catholic literary scholar and anthropologist René Girard interprets the Christian understanding of Satan in his analysis of the New Testament texts as one of the main motifs of Christian revelation. In the context of the mimetic theory formulated by him, the depiction of the devil in the Gospels is a paradigm of the mimetic cycle: The devil is the tempter and the founder of desire and " scandal " (skándalon), his work is the self-driving mimetic (= imitative ) Violence, and he is the "murderer from the beginning" who brings about the mythical religious system, the church myth of Christ, that is the becoming and worship of the Jewish traveling preacher, rabbi and messiah Jesus of Nazareth and the separation from Judaism. In the exposure of human (mimetic) violence through the Passion and in the subsequent end of the salvific sacrificial cult of the archaic world, the meaning of the triumph of the cross over the "powers and powers" of the Epistle to the Colossians ( Col 2: 14-15 EU ) and that To see the deception of the “rulers of this world” in 1 Corinthians ( 1 Cor 2, 6–8 EU ) ( Pauline theology and the “principle of evil” ), if one equates these and similar terms with Satan, as the church fathers did . Girard's view was received by some theological circles, but his ideas are unusual in Christian dogmatics and hardly known by the church public. However, he refers to Origen and his thesis of Satan deceived by the cross as the bearer of “an (r) important intuition”, which in the Western Church “came under suspicion of being 'magical thinking'”.

Iconography and popular beliefs

Iconographic attributes of the devil go back in part to pagan gods, for example with the Greek god Pan . The devil is usually depicted as black and hairy, with one or two goat or horse feet , ram horns and a tail. When he disappears, he also leaves a bad stench.

Islam

Even if Islam rejects the idea of absolute evil as an opponent of God, Islam knows a variety of personifications of evil. Among them the Dajal , the embodiment of the false prophet in the Islamic end times, the biblical Pharaoh, to whom the sin of being equal to God, is attributed, the gods of the pre-Islamic Arabs (Taghut), Cain, who is charged with murder in the To have brought the world, Iblis , the fallen angel and Satan , a power leading to evil. But every rational being, that is, the people and the jinn who are held responsible by God for their deeds, can be called devils (Shaitan, Arabic الشيطان, Plural شياطينShayāṭīn, identical in meaning and origin with Hebrew שטן= Satan) apply and are referred to as Satans of the al-Ins or "al-Jinn". The devils cause suffering, make life difficult for others, cause doubts in God and lead to evil.

Iblis, who is considered to be the seducer of men and jinn, did not rebel against God, but against the command to submit to man. So Iblis asked permission to mislead people. While Iblis himself does not represent a thoroughly evil figure, the term Satan only refers to evil forces, including Iblis, but only when he acts as a seducer. Under the influence of modern Salafist theology , the devil is increasingly replacing the former role of satans and jinn . In addition, the devil rises to be a permanent threat affecting both social and political affairs and acting to the detriment of Puritan Muslims, while the unbelievers are in constant danger of being under the influence of the devil.

The Sufism go against emphasizes a monistic conception of the world in which evil has not its own reality has, but is represented by one's ego. Here, too, figures such as Iblis and Pharaoh play an important role; they are both considered a symbol of human sins, such as pride (Pharaoh) and envy (Iblis). Satan also plays a role as a force that stimulates the evil inclinations of man ( nafs ).

Yezidism

The form of evil does not exist in Yezidism . The Yazidi idea is that God is omnipotent and that no other power can exist next to God. The Yazidis do not utter the word of evil because the utterance of this word alone is a question of the uniqueness of God. According to Yazidi belief, God would be weak if he allowed a second force to exist alongside him. This idea would not be compatible with the omnipotence of God.

Zoroastrianism

The religion of Zarathustra, Zoroastrianism , has a dualistic character: “And in the beginning there were these two spirits, the twins, who, according to their own words, are called good and bad in thinking, speaking and doing. The good traders made the right choice between them. "

Gérald Messadié sees Satan's change from the accuser in God's counsel to God's adversary as the takeover of Ahriman from Zoroastrianism; there the evil creator of the world and the good god Ahura Mazda are indeed antagonists.

In Zoroastrianism (also known as Zoroastrianism), souls cross the Činvat Bridge after death . This is where judgment is held: for the righteous person the bridge is wide as a path, for the other it is narrow as a knife point. The good get into the blissful realms of the paradise Garodemäna (later Garotman ), the "place of praise"; but the soul of the evil one comes to the "worst place", d. H. in hell. The demons of Zoroastrianism are called Daevas , Drudsch and Pairikas (Peri) and are sometimes thought of as fiends who are in fleshly intercourse with bad people and seek to seduce the good, and sometimes as treacherous demons who experience drought, bad harvests, epidemics and other plagues impose on the world.

The creation story of Zoroastrianism says that in the first 3000 years Ahura Mazda (God) first created the egg-shaped sky and then the earth and the plants through a long ruling breeze. In the second cycle of 3000 years the primeval animals and then primitive man emerged. This was followed by the break-in of the Anramainyu (the "devil"), who killed primitive man and the primitive animal and opened a period of struggle that only ended with the birth of Zarathustra. This event coincided with the 31st year of King Vistaspa's reign . And from then on, 3000 years will pass again until the savior Saoschjant is born, who will destroy the evil spirits and bring about a new, immortal world; the dead will also rise from the dead.

Instead of the one Messiah , three are mentioned in other passages, which means that this teaching differs from the corresponding one in the Old Testament. On the other hand, the doctrine of the resurrection even agrees in details with the Christian doctrine, so that the assumption that the latter is borrowed from the religion of the Zoroastrians who are close to the Hebrews has a certain probability in itself. In particular, the terms heaven and hell were not known in ancient Judaism.

Manichaeism

The Manichaeism , an already extinct religion that originated in the third century, taught a strong dualism between the forces of light and darkness. According to the Manichaean concept, God and the devil are completely different. Eons ago both principles of good and bad existed separately, but merged when the beings of darkness attacked the world of light. Manichaeism thus rejects the equation of the devil with the fallen angel, Satan; In Manichaeism, evil has no origin in the creative act or the heavenly world of God, but comes from his own kingdom, the world of darkness. The devil consists of five different shapes: a fish, an eagle, a lion, a dragon and a demon. Manichaeism calls the devil the "prince of darkness", but also calls him Satanas , Ahriman, al-ayṭān or Iblis al Qadim, depending on the audience . As an antithesis to the creative and good God, the devil can only reproduce through sexual intercourse, but not himself create beings from nothing. The children of the devil also include Saklas and Nebroel, two evil spirits in Gnostic literature. The deity with whom Moses spoke according to the Bible would have been, not God, but the prince of darkness.

Lucifer

The term Lucifer, which is also often used, is of non-Jewish origin: In ancient times , Lucifer was the name for the planet Venus ; in ancient Babylon, Venus was called the “day star”, “son of dawn” or “morning star” or “evening star”. The Roman mythology knows Lucifer, the son of Aurora , the goddess of the dawn. In Greek mythology , the goddess Eos is the counterpart to the Roman aurora. And here, too, this goddess had a son, whose name was Phosphoros or Eosphóros (Greek for 'light bearer'). This corresponds to the Roman Lucifer (Latin for 'light bearer' or 'light bringer'). Since in Isaiah 14:12 an angel falling down from the heavens [actually cherub , s. u.] of the dawn "is mentioned, the" shining star "of Isaiah 14:12 was reproduced in the Vulgate as" lucifer ".

Designations

Devil names

The names listed below partly denote the devil, partly one of several devils or a manifestation of the devil. See the respective explanation and the linked articles.

Abrahamic Religions

Names from the field of Judaism, Islam and Christianity (languages: Hebrew, Arabic, Greek, Latin, German):

- Asmodaeus , demon in the Talmud and name of the ruler of the Schedim

- Asazel (Hebrew), a devil figure at the time of the Second Jerusalem Temple who stole the secrets of heaven and taught people the art of making weapons. At that time this figure may have been a demonization of Prometheus , a titan who brought fire from heaven to man. That fire gave the Hellenistic culture the opportunity to manufacture weapons and a military advantage over the Jews, which is why, from a Jewish perspective, he was given the role of a diabolical fallen angel. It has its origin in the Bible, however, and represents a desert demon, which itself does not represent any danger, but corresponds to the ancient Egyptian deity of chaos, Seth , from whom this figure is likely to have been adopted.

- Azazil (Arabic); the name occurs in Arabic literature and Koran exegesis, but not in the Koran itself; often as the name of Iblis before his exile

- Baphomet

- Beelzebub (Hebrew-Latin, from Ba'al Sebul, "Prince Ba'al")

- Belial (Hebrew, Latin) or Beliar (Greek); a demon in the Jewish Tanach or in the Old Testament

- Chutriel; he is destined to scourge the damned in hell

- Diabolos (Greek) or Diabolus (Latin); derived from this the adjective diabolic ("devilish")

- Iblis , a devil figure in the Koran. The name has not yet been found in pre-Islamic literature, but in the Christian "Kitab al Maghal", where it also denotes a name of Satan.

- Legion , name of a demon in the New Testament

- Lucifer (German) or Lucifer (Latin, literally "light bearer", "light bringer"), name of the fallen angel

- Mastema, a devil in the jubilee book

- Mephistopheles , in short: Mephisto, literary figure in Goethe's drama Faust

- Phosphoros (Greek, literally "light bearer", "light bringer", cf. Lucifer),

- Samael (Hebrew), also Sammael or Samiel; Israel's main accuser in the Jewish tradition and a false god in Gnosis

- Satan or Satanas (Hebrew), opponents

- Schaitan or Scheitan (Arabic), name for the supreme tempter and his successors in Islam

- Urian , Mr. Urian

- Voland ( Middle High German vâlant ), old name of the devil, also in medieval northern France

Other religions and languages

- Angat ( Madagascar )

- Bies [spoken bjes ] (in Polish and some other Slavic languages)

- Czort (in Polish and some other Slavic languages)

- Čert (in Czech )

- Kölski ( Iceland )

- Milcom, ammonite devil

- Ördög (in Hungarian )

- Pii Saart ( Thailand )

- Yerlik or Erlik denotes a diabolical figure in the ( Old Turkish ) language. The shamanistic world views are diverse, and so are the myths about Erlik's origin. According to a creation myth, God and his first creature, identified with Erlik, swam in the eternal ocean. Then when God wanted to create the world, he sent Erlik to the bottom of the ocean to collect earth from which creation would arise. But Erlik hid part of the collected earth in his mouth to create his own realm. When Erlik almost choked on it, God helped him spit out the hidden earth, which then became all unpleasant places in the world. God angrily punished Erlik by granting him his own kingdom, but assigning it to the underworld, whereupon Erlik became the deity of the underworld. According to the mythology collected by Vasily Verbitsky from Turks in the Altai region, Erlik was cast out by the heavenly beings along with spirits who followed him. In the practical living out of faith, Erlik are sometimes sacrificed to appease him. So-called “shadow shamans” trace their teachings back to Erlik himself and believe that after her death with Erlik they will enjoy a higher rank in the underworld. In addition to elementals cast out by heaven, Erlik is in command of other demons such as Körmös and Hortlak .

Paragraphs and covering designations

Some people assume that mentioning the devil's name could lead to his being called. There are therefore a multitude of disguising names and descriptions for the devil. Another reason for using a paraphrase may be to emphasize an aspect of one's being. Examples:

- Incarnate

- Gottseibeiuns (popular)

- Daus (popular, outdated), contained in the phrase "ei der Daus"

- Adversary

- Seducer

- Lord of hell

- Cuckoo ("Get the cuckoo")

- Höllenwart (derived from the old devil names "Hellewart", "Hellewirt" or "Hellehirt")

- Prince of this world

- Son of damnation

- fallen morning star

- Lord of the Flies (literal translation from Hebrew Beelzebub )

- Thousand artist ( latin milleartifex )

- (Old) Nick, English nickname for the devil (used for example in the film The Cabinet of Dr. Parnassus )

- Old Scratch or Mr. Scratch, English nickname for the devil (used for example in the story A Christmas Carol )

Deities identified with the devil

There are deities from other religions and mythologies who have been identified with the devil within Christianity.

The devil in psychoanalysis

In 1922, the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud dealt with the Christian folk belief in the devil. In the essay published in 1923, A Devil's Neurosis in the Seventeenth Century (XIII, pp. 317-353), he rated church pastoral care as not helpful in dealing with sick people. The diagnosis of the clinical picture of the Bavarian Catholic Christian, painter and Teufelsbündler Christoph Haitzmann , who in 1669 had committed himself to the devil with his own blood, was: "Depression that has not been dealt with as a result of the loss of a loved one". The legend has passed down the following events: On September 8, 1677 on the day of the birth of Mary , during an exorcistic practice at midnight in the pilgrimage church of Mariazell, the devil appeared as a winged dragon to Christoph Haitzmann in the presence of monks.

“We know of the evil demon that he is intended as an opponent of God and yet is very close to his nature [...] It doesn't take a lot of analytical acumen to guess that God and the devil were originally identical, a single figure that later became two with opposite properties was broken down ... It is the well-known process of breaking down an idea with [...] ambivalent content into two sharply contrasting opposites. "

According to the psychoanalyst Slavoj Žižek , not only does the devil "function as diabolos (from diaballein: separate, pull one into two) and Jesus Christ as his opposite, as a symbol (to symbolize: collect and unite)". Rather, according to Lk 14.26 EU , Jesus Christ himself is the separator (diabolos) and both the devil and Judas Iscariot are merely his supporters.

Cultural and historical significance

The devil in a fairy tale

Numerous fairy tales tell - mostly contrary to Christian dogmatics - of a devil who often has comical traits. These include B. KHM 29 The devil with the three golden hairs , KHM 100 The devil's sooty brother, KHM 125 The devil and his grandmother or KHM 189 The farmer and the devil.

The devil in film and television

Many actors have embodied the devil over the course of time, with a wide variety of approaches, from very humorous to extremely serious and nasty:

- John Gottowt - 1913 in The Student of Prague

- Reinhold Schünzel - 1919 in Uncanny Stories

- Benjamin Christensen - in 1922 in Häxan

- Emil Jannings - 1926 in Faust - a German folk tale

- Werner Krauss - 1926 in The Student of Prague

- Theodor Loos - 1935 in The Student of Prague

- Walter Huston - 1941 in The Devil and Daniel Webster

- Laird Cregar - 1943 in A Heavenly Sinner

- Vincent Price - 1957 in The Story of Mankind

- Gustaf Gründgens - 1960 in Faust

- Julie Newmar - 1963 in Twilight Zone (Of Late I Think of Cliffordville)

- Eddie Powell - 1967 in The Devil's Bride

- Burgess Meredith - 1967 in The Torture Garden of Dr. Diabolo

- Christiane Schröder - 1971 in The Devil in Love

- Christopher Lee - 1971 in Poor Devil

- Dieter Franke - 1977 in Who will tear away from the devil

- Patrick Macnee - 1978 in Battlestar Galactica (TV Series)

- Horst Frank - 1979 in Timm Thaler (TV series)

- Danny Elfman - 1980 in Forbidden Zone

- David Warner - 1981 in Time Bandits

- Tim Curry - 1985 in Legend

- Jack Nicholson - 1987 in The Witches of Eastwick

- Robert De Niro - 1987 in Angel Heart

- Roberto Benigni - 1988 in A Heavenly Devil

- Jeff Goldblum - 1990 in The Devil Mr. Frost

- Max von Sydow - 1993 in In a small town

- Viggo Mortensen - 1995 in God's Army - The Last Battle

- Al Pacino - 1997 in On behalf of the devil

- Robert Englund - 1997 in A Terribly Nice Family

- Gabriel Byrne - 1999 in End of Days

- Harvey Keitel - 2000 in Little Nicky - Satan Junior

- Elizabeth Hurley - 2000 in Devilish

- Armin Rohde - 2002 in 666 - Don't trust anyone you sleep with!

- Rosalinda Celentano - 2004 in The Passion of the Christ

- Peter Stormare - 2005 in Constantine

- John Light - 2005 in The Prophecy: Uprising

- Peter Fonda - 2007 in Ghost Rider

- Dave Grohl - 2007 in Kings of Rock - Tenacious D

- Christoph M. Ohrt - 2007 in A devil for the Engel family

- Ray Wise - 2007 to 2009 in Reaper (TV series)

- Bryan Cranston - 2008 Fallen Angels 3

- Mark Pellegrino - 2009 in Supernatural (TV Series)

- Tom Waits - 2010 in The Cabinet of Dr. Parnassus

- Nicholas Ofczarek - 2012 in Jesus Loves Me

- Philip Davis - 2013 in Being Human (TV Series)

- Tom Ellis - 2016 in Lucifer (TV Series)

- Justus von Dohnányi - 2017 in Timm Thaler or The Laughter Sold (film)

Many other films deal with the devil:

- Rosemary's Baby (1968)

- The Exorcist (1973)

- The Omen (1976)

- Exorcist II - The Heretic (1977)

- Halloween the night of horror (1978)

- The Last Temptation of Christ (1988)

- The Nine Gates (1999)

- Exorcist: The Beginning (2004)

- The Exorcism of Emily Rose (2005)

- Requiem (2006)

- The Omen (2006)

- The Reaping: The Messengers of the Apocalypse (2007)

- Gonger - Evil Never Forgets (2008)

- Gonger 2 - Evil Returns (2010)

- Devil (2010)

The devil in music and literature (selection)

The tritone , frowned upon in the Middle Ages, was also referred to as the diabolus in musica (Latin: 'devil in music') or the devil's interval . Since the song Black Sabbath by the band of the same name , which is based on the tritone, this has been a trademark of their "evil" sound. The title of the album Diabolus in Musica by the metal band Slayer also alludes to the tritone.

The devil's violin is a simple rhythm and noise instrument.

The devil is the theme of the following pieces of music (selection)

- Giuseppe Tartini : Devil's Trill Sonata for the violin (18th century)

- The Rolling Stones : Sympathy for the Devil (1968)

- AC / DC : Highway to Hell (1979)

- Marilyn Manson : You and Me and the Devil Makes 3 (2007)

The story The Devil on Christmas Eve by Charles Lewinsky offers a cheerful view of the devil . In the text, the devil visits the Pope to seduce him. He does.

In the work The Master and Margarita by the Russian writer Michail Bulgakov , the magician Voland embodies the devil and is assisted by characters named Behemoth , Asasselo and Abaddon .

Wanders German Proverbs Lexicon offers 1700 proverbs with the word devil .

The devil in the theater

In the play Kasper saves a tree, staged by Martin Morgner (first performance 1986), the Baron Lefuet represents the devil.

The devil in the puppet show

In traditional puppet theater , the devil appears as the incarnation of evil. He contrasts figures that embody the principle of the good, such as puppets , fairies or angels . In the classic puppet show by Dr. Faustus plays the role of the devil as Mephistopheles in the role of the counterpart and companion of the main character Faust. In the modern traffic junk game, the devil acts as a seducer who wants to tempt people to behave in a way that is illegal, accident-prone and anti-cooperation. In this role he reflects the destructive tendencies in people, which are determined by self-interest, gainfulness, striving for power and other vices and are already found in child behavior. The characters in the puppet theater have experienced different interpretations in the course of their long theater history. In the pedagogically oriented modern traffic theater, the rigid typology and the fixation on the eternal evil is partly abandoned and with the help of the audience itself the devil is given the chance of an ultimate conversion to the good and useful.

Depending on the type of puppet theater, the figure of the devil can be found in the form of a hand puppet , stick puppet or marionette .

Survey

According to a survey of 1003 people in Germany in March 2019, 26 percent believe in the existence of a devil. The situation in the USA in 1997 was comparable.

literature

- Daniel Arasse : Portraits of the Devil. With an essay by Georges Bataille . Matthes & Seitz, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-88221-588-5 .

- Verena Bach: In the face of the devil. Its appearance and representation in film since 1980. Herbert Utz Verlag, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-8316-0636-6 .

- Klaus Berger : What is the devil there for? Gütersloher Verlagsanstalt, Gütersloh 2001, ISBN 3-579-01454-4 .

- Maria-Christina Boerner: Angelus & Diabolus. Angels, devils and demons in Christian art. Edited by Rolf Toman . Verlag H. F. Ullmann, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-8480-0771-4 .

- Anna Maria Crispino, Fabio Giovannini, Marco Zatterin (eds.): The book of the devil. History, cult, manifestations. License issue. Gondrom, Bindlach 1991, ISBN 3-8112-0909-4 .

- Alfonso M. DiNola: The devil. Essence, effect, history. Dtv, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-423-04600-7 .

- Kurt Flasch : The devil and his angels. The new biography. C. H. Beck, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-406-68412-8 ( Review. In: Die Welt. September 16, 2015).

- René Girard : I saw Satan fall from the sky like lightning. Hanser, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-446-20230-7 (original edition: Je vois Satan tomber comme l'éclair. 1999).

- Bruno Gloger, Walter Zöllner : Faith in the devil and witchcraft. Koehler & Amelang, Leipzig 1983.

- Herbert Haag : Belief in the devil. Katzmann, Tübingen 1980, ISBN 3-7805-0393-X .

- Marianne Hauser: Shaping Evil. Phenomenology of its origin and approaches to its conceptual foundation. Altenberge (Oros) 1986.

- Wassilios Klein, Kirsten Nielsen u. a .: devil. In: Theological Real Encyclopedia . 33 (2002), pp. 113–147 (religious-historical, biblical, church-historical, dogmatic and iconographic aspects).

- Anton Szandor LaVey : The Satanic Bible and Rituals. SecondSight, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-935684-05-3 .

- Charles Lewinsky : The devil on Christmas night. Verlag Nagel & Kimche, Zurich 2010, ISBN 978-3-312-00465-2 .

- Jan Löhdefink: Times of the Devil. Concepts of the devil and historical time in early Reformation pamphlets (1520–1526). Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2016, ISBN 978-3-16-154449-1 .

- Sylvia Mallinkrodt-Neidhardt: Satanic Games. The renaissance of Teufel and Co. A critical analysis. Neukirchener Verlagshaus, Neukirchen-Vluyn 2002, ISBN 3-7975-0049-1 .

- Peter Maslowski : The theological monster. The so-called devil and his story in Christianity. IBDK-Verlag, Berlin 1978.

- Fritz Mauthner : History of the Devil. In: Ders .: Atheism and its history in the West. 4 volumes. Volume 1: Introduction. Fear of the devil and enlightenment in the so-called Middle Ages. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart / Berlin 1920, first book. Second section, pp. 186–221 ( scan of the first edition of the French National Library in Fraktur ; scan of the complete, corrected new edition. M-presse, Heppenheim 2010 in the Google book search, ISBN 978-3-929376-66-1 ).

- Gerald Messadié : Devil, Satan, Lucifer. Universal history of evil. Komet-Verlag, Frechen 1999, ISBN 3-933366-19-4 .

- Paul Metzger: The devil (= Marix knowledge ). Marixverlag, Wiesbaden 2012, ISBN 978-3-86539-969-4 .

- Elaine Pagels : Satan's Origin. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1996, ISBN 3-518-39368-5 .

- Egon von Petersdorff: Daemonologie (Vol. 1: Demons in the world plan. Vol. 2: Demons at work ). Christiana publishing house, Stein a. Rhine 1995.

- Chris Redstar: Greetings from Hell. Confessions of a Satanist. BoD, Norderstedt 2004, ISBN 3-8334-2014-6 .

- Kurt Röttgers : Devils and Angels. transcript, Bielefeld 2005, ISBN 3-89942-300-3 .

- (Georg) Gustav Roskoff : History of the devil. A cultural-historical satanology from the beginnings to the 18th century. Greno, Nördlingen 1987, ISBN 3-89190-805-9 .

- Walter Simonis : Where does evil come from? ... when God is good. Graz 1999, ISBN 3-222-12740-9 .

- Walter Simonis: About God and the World. God and creation doctrine. Düsseldorf 2004, ISBN 3-491-70375-1 .

- Wolfgang Wippermann : Racial madness and belief in the devil. Frank & Timme, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-86596-007-3 .

Web links

- Stefan Greif: Do you like the devil? To the devil image of Goethe's time. In: goethezeitportal.de ( PDF ; 256 kB)

- Joseph Jacobs , Ludwig Blau : Satan. In: Isidore Singer (Ed.): Jewish Encyclopedia . Volume 11, Funk and Wagnalls, New York 1901-1906, pp. 68-71 .

- www.infranken.de: Petra Malbrich: Pope Francis warns of the devil: does he exist? (Interview with Hans Markus Horst).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Na'ama Brosh, Rachel Milstein, Muzeʼon Yiśraʼel (Jerusalem) Biblical stories in Islamic painting. Israel Museum, 1991, p. 27 (English).

- ^ Paul Carus : The History of the Devil and the Idea of Evil. 1900, pp. 104–115 ( online ) (German: The history of the devil from the beginnings of civilization to modern times. Bohmeier Verlag, Leipzig 2004, ISBN 978-3-89094-424-1 ).

- ↑ Satan is a Hebrew title, usually an angel , which roughly corresponds to that of an accuser. Lucifer ("light bearer") is also the Latin name of the morning star .

- ↑ Reiner Luyken : There is no more fire in hell. (No longer available online.) In: zeit.de. March 8, 1996, archived from the original on February 22, 2017 ; accessed on January 15, 2019 (source: Die Zeit , 11/1996).

- ↑ Zeki Saritoprak The Legend of al-Dajjal (Antichrist): The Personification of Evil in the Islamic tradition 14 April 2003 Wiley Online Library

- ^ Amira El-Zein: Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn (= Contemporary issues in the Middle East ). Syracuse University Press, Syracuse, N.Y. 2009, ISBN 978-0-8156-5070-6 , p. 45 (English).

- ↑ Michael Kiefer, Jörg Hüttermann, Bacem Dziri, Rauf Ceylan, Viktoria Roth, Fabian Srowig, Andreas Zick: "Let us make a plan in sha'a Allah". Case-based analysis of the radicalization of a WhatsApp group. Springer-Verlag, 2017, ISBN 978-3-658-17950-2 , p. 111.

- ↑ Thorsten Gerald Schneider's Salafism in Germany: Origins and Dangers of an Islamic Fundamentalist Movement transcript Verlag 2014 ISBN 9783839427118 p. 39.

- ↑ Peter J. Awn Satan's Tragedy and Redemption: Iblis in Sufi Psychology BRILL 1983 ISBN 9789004069060 p. 93 (English).

- ↑ Willis Barnstone, Marvin Meyer The Gnostic Bible: Revised and Expanded Edition Shambhala Publications 2009 ISBN 978-0-834-82414-0 pp. 575-577.

- ↑ Peter J. Awn Satan's Tragedy and Redemption: Iblis in Sufi Psychology BRILL 1983 ISBN 9789004069060 (English).

- ^ Acta Archelai of Hegemonius, Chapter XII, c. AD 350, quoted in Translated Texts of Manicheism, compiled by Prods Oktor Skjærvø, p. 68 (English).

- ↑ George WE Nickelsburg: Apocalyptic and Myth in 1 Enoch 6-11. In: Journal of Biblical Literature. Volume 96, No. 3.

- ↑ Egypt and The Bible The Prehistory of Israel In the Light of Egyptian Mythology. Brill Archive.

- ↑ Because the Baal statues were also sacrificed in summer, the sacrificial blood attracted the flies. The name is therefore polemically translated as " Lord of the Flies ". Through various readings, Baal Sebul later became Beelsebul, from which folk etymology became Beelzebub .

- ↑ Monferrer-Sala, JP (2014). One More Time on the Arabized Nominal Form Iblīs. Studia Orientalia Electronica, 112, 55-70. Retrieved from https://journal.fi/store/article/view/9526

- ↑ Voland is also the name of the devil in Mikhail Bulgakov's novel The Master and Margarita .

- ↑ Vísindavefurinn: How many words are there in Icelandic for the devil? Visindavefur.hi.is, accessed April 5, 2012 .

- ↑ David Adams Leeming, A Dictionary of Creation Myths, Oxford University Press, 2014, ISBN 9780195102758 p. 7

- ↑ Fuzuli Bayat Türk Mitolojik Sistemi 2: Kutsal Dişi - Mitolojik Ana, Umay Paradigmasında İlkel Mitolojik Categoriler - İyeler ve Demonoloji Ötüken Neşriyat A.Ş 2016 ISBN 9786051554075 (Turkish)

- ↑ AB Sagandykova, Assylbekova, BS Sailan GS Bedelova and Tuleshova The Ancient Turkic Model of Death Mythology Medwell Journals, 2016 ISSN 1818-5800 p. 2278

- ↑ According to the Duden, the connection is uncertain; see. "Daus" .

- ↑ Cf. Meinolf Schumacher : The devil as 'a thousand artists'. A word history contribution. In: Middle Latin Yearbook . Volume 27 (1992), pp. 65-76 ( PDF; 1.4 MB ).

- ^ "Anno 1669, Christoph Haitzmann. I dedicate myself to being Satan, I will be his serf son, and in 9 years I will belong to him with my body and soul. ”Quoted from Rolf Kaufmann: The good thing about the devil. Cape. Decay of the archaic worldview in the Occident ( Memento from April 20, 2008 in the Internet Archive ), para. 106. In: opus-magnum.de, accessed on October 15, 2012.

- ↑ See the first edition in: Imago . Journal of the Application of Psychoanalysis to the Humanities. 9th vol., Vol. 1, pp. 1-34 on Wikisource .

- ↑ Slavoj Žižek : STAR WARS III. About Taoist Ethics and the Spirit of Virtual Capitalism. In: Lettre International . No. 69, Summer 2005, 54, accessed on March 13, 2015.

- ^ Jacob Grimm , Wilhelm Grimm : Children's and house fairy tales. Collected by the Brothers Grimm. Bookshop of the Royal Secondary School in Berlin, 1812/1815.

- ↑ Charles Lewinsky: The devil on Christmas night. Haffmans, Zurich 1997; Nagel & Kimche, Zurich 2010, ISBN 978-3-312-00465-2 .

- ↑ Wolfgang Schneider : Masterpiece of magical realism. In: deutschlandfunkkultur.de . August 17, 2012, accessed on January 15, 2019 (review of the edition: Galiani, Berlin 2012, translated from Russian and edited by Alexander Nitzberg ).

- ^ Karl Friedrich Wilhelm Wander : German Sprichwort Lexikon. Reprint in different versions.

- ↑ Manfred Wegner (ed.): The games of the doll. Contributions to the art and social history of puppet theater in the 19th and 20th centuries. Cologne 1989.

- ^ Wolfram Ellwanger, A. Grömminger: The hand puppet show in kindergarten and elementary school. Herder, Freiburg 1978.

- ↑ Siegbert A. Warwitz : The traffic jasper is coming or what the puppet game can do. In: Ders .: Traffic education from the child. Perceive-play-think-act. 6th edition. Schneider, Baltmannsweiler 2009, pp. 252-257.

- ^ K. Wagner: Traffic education then and now. 50 years of Verkehrskasper. Scientific state examination work (GHS), Karlsruhe 2002.

- ↑ Dietmar Pieper: "The sky is empty" . In: Der Spiegel . No. 17 , 2015, p. 40-48 ( online - April 20, 2019 ).

- ↑ Gustav Niebuhr: Is Satan Real? Most People Think Not.

- ↑ A satire on the way the Catholic Church deals with the devil.