Stonehenge

Coordinates: 51 ° 10 ′ 44 " N , 1 ° 49 ′ 35" W.

Stonehenge [ stəʊ̯n'hɛndʒ ] is a building near Amesbury , England, which was built in the Neolithic and used at least until the Bronze Age .

It consists of a ring-shaped earth wall, inside of which there are various formations of worked stones grouped around the center. Because of their gigantic size, they are called megaliths . The most noticeable of these are the large circle of formerly 30 standing cuboids, which originally had a closed ring of 29 segments on their upper side, and the large horseshoe made of originally ten such columns, each of which was connected to five pairs by a capstone. the so-called triliths . Within each of this horseshoe and circle stood two figures similar in shape: both made of much smaller, but formerly twice as many stones.

These four formations are supplemented by the "altar" near the center of the complex, the so-called "sacrificial stone" inside - and the heelstones a good bit outside of the northeast exit. In addition, three concentric circles of holes were created within the ring wall and in the largest of them four menhirs were stationed so that they form a rectangle. Other buildings from the megalithic era - above all barrows and two structures known as racecourses - can be found in the area. There also seems to have been a processional path that led from the exit mentioned to the right to the bank of the Avon. The radius that leads down to the entrance of the monument then points in its extension to the south coast of England, interestingly exactly at the point where the rivers Avon and Stour join the English Channel. According to this, a ceremonial procession could have taken place in the sense of a circular movement following the course of the sun , which began on a certain morning in the northeast and ended in the evening coming up from the south.

There are various hypotheses , some complementing one another, and some contradicting one another, about the reason for and the ultimate purpose of this elaborately designed complex . These range from a self-portrait of a primordial political alliance between two formerly hostile tribal organizations (hierarchy of size of the menhirs) to a burial site, an astronomical observatory including a calendar for the sowing and harvesting times to a religious place of worship.

All of these speculations, even the rather absurd ones, agree on one point: The architects of the monument succeeded in aligning the horseshoes and the stones placed vertically in front of their openings exactly with the sunrise on the day of summer turning.

The path from the simplest to the most complex, final version of this system can be divided into at least three sections:

- The first phase, during which a circular earth wall with a surrounding ditch was built, is dated around 3100 BC. Dated.

- The Aubrey holes as the largest of the three circles of holes mentioned at the beginning, plus additional holes outside the ring wall, date from around the early third millennium BC. BC (see chapter Stonehenge 1 ). They are usually interpreted to mean that they served as burial chambers and / or received wooden posts.

- The stone structures were built from around 2500 to 1700 BC. BC, whereby earlier versions were radically modified several times.

According to first vague indications, the beginnings of the complex as an actually megalithic monument go back significantly further than previously assumed; so it seems as early as 3000 BC To have given a first version of stone structures. The further statements in this article refer to the date that was previously assumed to be certain.

The latest research suggests that the place where the remains of the monument can be seen today had a special ritual significance for the people as early as 11,000 years ago .

The UNESCO declared the Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites in 1986 for World Heritage . The monument has been owned by the English state since 1918; It is managed and developed for tourism by the English Heritage , and its surroundings by the National Trust .

overview

The name Stonehenge is already recorded in Old English as Stanenges or Stanheng . While the first part of the name is the Old English word stān "stone", the second element is unclear. It could be hencg "angel, hinge" or a noun derivation from the verb hen (c) en "hang", which would then mean "gallows". Indeed, medieval gallows had two feet, thus resembling the triliths in the center of the monument. The attempted interpretation as "stones hanging (in the air)" lacks semantic consistency.

The second component of the name, Henge , is used today as an archaeological technical term for that class of Neolithic buildings that consist of a ring-shaped raised enclosure with a recess (ditch) running along the inside. Stonehenge itself is what is known as an atypical henge according to current terminology , as the moat is outside the ring wall.

The complex was built or continuously changed in several phases, which extend over a period of about 2000 years. However, it can be proven that the site was already in use before the first stone construction. Three large presumed post holes near the present parking lot date from the Mesolithic , around 8000 BC. In the vicinity of the cult site, ash remains from cremations from the period between 3030 and 2340 BC were found in soil samples. BC, suggesting that the site was in use as a burial site before the stones were erected. The most recent cultic activities (druids, origin of the Avalon saga?) Date from around the 7th century AD, the grave of a decapitated Anglo-Saxon should be mentioned as a specific artifact .

It is difficult to date the various phases of the monument's design and to understand their meaning , as earlier excavation methods did not meet today's standards and there are still hardly any theories that would enable one to empathize with the thoughts and actions of the people of that time.

So it remains uncertain what the function of the holes found in the ground was. Some scientists consider that their original task was to include supporting pillars for the purpose of no less speculative roofing of the square. Others, on the other hand, argue that such hypothetical tribes were merely phallic symbols or totem poles , which were later replaced by towering rocks in the course of technological advances and cultural and demographic changes (population growth, increase in labor force).

One understands intuitively that the purpose of such constructions is to impress the viewer from a distance; H. also, to make enemies consider whether they dare to attack. The successive expansion of the facilities could then be interpreted as a symbolic "arms race" among neighboring tribes. The question remains whether such a dynamic is compatible with the long periods of further development of the monument. It was also assumed that memories of military conflicts might be reflected in the structures of Stonehenge, for example the displacement of a larger number of 'indigenous people', embodied by the (?) Bluestones, who were temporarily removed from the ring wall. The fact that this defeated culture was subsequently integrated into the dominion of the victors - perhaps symbolized by the huge sarsen horseshoe - would then correspond to the often observed result of a previous territorial conflict. (See also below, in the chapter Urpolitik in the context of bluestones and the commentary in section Phase 3 III .)

The fact that so far only little material has been discovered from which 14 C data could be obtained makes it more difficult to understand the temporal development of these cultures, and thus also the gradually made changes to the shape of the monument that were only archaeologically discovered. The sequence of these interventions that is most commonly accepted today is explained in the following text with reference to the plan sketch shown. The megaliths that are still found today are highlighted by coloring their outlines (blue, brown and black); the capstones were left out for the sake of clarity and speculation is being made about the disappeared remainder of the severely damaged complex. During the feudal phase of England, the monument was partly used as a quarry for the construction of churches, fortresses and palaces of the mighty, on the other hand there are clear traces of deliberate destruction. Carefully dismembered columns, smashed portraits etc. are mostly interpreted by today's archeology in terms of the destruction of a culture by the subsequent victors; at the same time it appears from around 1400 BC. To have come to a change in burial customs (from megalithic communal graves to graves for individual rulers), which can also be interpreted in this sense.

The attachment

The heel stone and the sacrificial stone and with them the openings of the two central horseshoes were aligned with the position of sunrise at midsummer; Besides others, the four stones of the rectangular structure on the ring wall seem to have to do with different periodicities of celestial mechanics . For these reasons, it is often assumed that Stonehenge was a prehistoric observatory , although the exact type of use and its importance, for example for sowing and harvesting at the best possible times (see below), are still being discussed.

Description of the stones (from the inside out)

- The altar stone: a five-meter block of green sandstone closest to the center of the complex.

- The little horseshoe closes immediately : it housed 19 stones made from dolerite , a very hard basalt from the Preseli Mountains in south-west Wales . Because of their bluish shimmer, the megaliths of this material are also known as bluestones. Its height reaches up to 2.8 m (towards the open legs it decreases to 70 cm), and its shape is typical of the conical shape of the Stone Age obelisk. A striking feature is that the two stones left and right of the base of this horseshoe show a cross-section that corresponds to the geometry of a tongue and groove connection from the carpentry trade.

- The big horseshoe includes the small one. It consisted of ten sandstone blocks (so-called sarsen ), which were connected in twos by a third on the top. With a height of over 5 m, they weigh up to 50 tons and must have been moved on sledges that were pulled by an estimated 250 men on inclines of up to 1000 men. Alternatively, the use of draft animals is discussed.

- The circle of originally 60 bluestones follows the mighty sarsen horseshoe. On average, they are a good deal smaller than those of the bluestone horseshoe and their shape is cylindrical (instead of conical).

- The formation of this bluestone circle surrounds another circle, which in turn was constructed from sarsen: originally 30 in number, approx. 4.5 m high and connected by 29 placed blocks so that a closed ring structure was created.

- The sacrificial stone , the name of which is also misleading because it can easily be confused with the altar stone , is currently in the middle of the northeast opening of the ring wall, in a sense at the exit of the complex. The audio guide, which is used to guide visitors around the monument, states that this stone was probably upright and that its red spots are not blood (which would have long since been weathered and washed off), but iron oxide inclusions . The name "sacrificial stone" is therefore more than questionable.

- The Heelstone or Friars Heel, referred to in German as "heel stone", stands relatively far outside the ring wall.

- The four station stones .

Other special features:

- The Aubrey holes (56 pieces)

- The Y and Z holes (29 and 30)

On behalf of English Heritage , laser scans were made of the surfaces of all 83 monumental Stonehenge stones that were still preserved. A total of 72 previously unknown engravings were discovered. 71 of them show axes (up to 46 cm tall), one a dagger. The complex is similar to the stone circles in northern Scotland known as the Ring of Brodgar .

History of origin

In 1995 the excavation findings of the 20th century were evaluated and based on 14 C dating, they were divided into three phases. A slight change made in 2000 to an older date is based on the method that has since been improved ( Bayesian statistics ) to evaluate the 14 C data. Further minor modifications were added until 2009.

Based on their own evaluations, employees of the latest data surveys presented a new study at the end of 2012 in which they proposed five phases instead of the previous three - also using a Bayesian classifier. A similar interpretation had already been made in 1979, but received little attention.

Stonehenge 1

The first structure was about 115 m in diameter and consisted of a circular wall with a ditch surrounding it (7 and 8), which is classified according to an atypical henge system. The large, northeast-facing opening of this ring wall was opposite a smaller one in the south (14) ; Deer and ox bones were placed at the bottom of the trench. These bones were much older than the antler picks used to dig the trench and were well preserved when they were buried. This first phase is dated to around 3100 BC. Dated. At the outer inner edge of the area enclosed in this way, there was a circle of 56 holes (13). These Aubrey holes , named after their discoverer, John Aubrey , a 17th century historian, may once have been designed to hold wooden pillars in place.

A second wall (9) now surrounding the ditch could also originate from this phase (Stonehenge 1), which is to be defined as pre-megalithic .

Stonehenge 2

There are no longer any visible remains that could safely indicate the appearance of the building structures during the second phase. The dating done therefore more indirect, among other finds from "grooves Ceramics" ( English Grooved Ware ), which in this period ( late Neolithic ) belong. Forms of holes detectable in the ground could be in the early third millennium BC. BC and have carried posts. More posts could have been in holes discovered at the north entrance; two parallel rows of posts would have run from the south entrance into the interior. However, at least 25 of the Aubrey holes contained remains of cremation burials dating from around two centuries after the holes were built. The holes were used as burial places - if necessary, they were converted for this purpose, or the hypothetical posts were removed at every burial. The remains of thirty other cremations were discovered in the ditch and at other points of the complex, mostly in the eastern half. Unburned pieces of human bones from this period were also found in the trench.

Stonehenge 3 I.

In the center of the sanctuary, around 2600 BC Two concentric semicircles made of 80 stones, the so-called bluestones , were created. They were moved later, but the holes in which the stones were originally anchored (the so-called Q and R holes) have remained detectable. Again there is little dating evidence for this phase. As already mentioned, the bluestones come from the area of the Preseli Mountains , which are about 240 km from Stonehenge in what is now Pembrokeshire in Wales. The stones are mostly made of dolerite , interspersed with some inclusions of rhyolite , tuff and volcanic ash. They weigh about four tons. Known as the Altar Stone (1), the six-ton stone is the only one made from green sandstone. It is twice the size of the largest of the bluestone horseshoe stones (which does not yet exist at this stage) and is also from Wales. It is no longer possible to clarify whether it was due to ice-age earth movements or human will. Perhaps it stood upright in the center as a large monolith , perhaps it was intended that it should lie down. Many of the early megalithic complexes represent burial facilities: the giant graves , also known as the devil's beds.

At that time, the entrance was widened so that its two side parts now pointed exactly to the positions of the sunrises at the time at the summer and winter solstice . As mentioned, the bluestones were removed after a while and the remaining holes (Q; R) filled.

The heelstone (5) may also have been placed outside the northeast entrance during this period. The dating is uncertain, however, in principle every section of the third phase comes into question. There was possibly a second stone, but it can no longer be found. Two, possibly three large stones were placed inside the northeast entrance (pressure compaction in the ground). Only one of them, 4.9 m long, remained in its place - overturned - and is known as the sacrificial stone (4).

Phase 3 also includes the construction of the four station stones (6) and the construction of the avenue (10), a path bordered on both sides by a moat and earth wall, which is also known as the processional path and leads over a distance of 3 km to the Avon River. Investigations of this route showed that it ran through a meltwater channel from the last Ice Age, which was only slightly reworked.

At some point in the third construction phase, trenches were dug both around the two station stones on the north-south diagonal and around the heelstone, which must have stood as a single monolith since then. This phase of the construction of Stonehenge is what the Archer of Amesbury should have seen; towards the end of the phase, Stonehenge seems to have replaced the Henge of Avebury as the central cult site of the region.

Stonehenge 3 II

At the end of the third millennium BC, according to radiocarbon dates between about 2440 and 2100 BC. BC, the main building activity took place. Now the two Sarsen constructions (gray in the plan) were erected, which determine the overall impression of Stonehenge today. Many of these 74 megaliths, the smaller 25 and the large 50 tons, come from a quarry 30 km to the north near Marlborough , according to geochemical tests in 2020.

30 of these blocks formed a circle with a diameter of thirty meters. That there were once 30, grouped into a complete circle, could only be proven in 2013, when a long-lasting drought caused by differences in the vegetation showed the compaction in the subsoil even where the stones themselves are no longer present. The horseshoe from the 5 triliths was then set up within this circle .

The surfaces of all sarsen are hewn and smoothed. The capstones of the sarsen formations (circle + horseshoe) received two holes on their underside, which complement each other with the pegs on top of the supporting stones to form a version of the tongue and groove connection . A symbolic purpose of this measure cannot perhaps be ruled out, but it certainly served to wedge the elements together. Something similar can be found on the end surfaces to the left and right of each of the 29 capstones of the circle, and they were also given the shape of carefully crafted circular segments in order to connect them to form a perfect ring.

There are also chiseled or scratched images on some of the sarsen. Perhaps the oldest, a flat rectangular figure on top of the inside of the fourth trilith, could represent a mother goddess. Perhaps closer than this interpretation would be to think of an abstract representation of the 4 station stones opposite this symbol - but here too it is still open what their meaning is. Fewer questions remain with regard to the other symbols. Particularly noteworthy are the depiction of a bronze dagger and fourteen ax heads on stone 53, further depictions of ax heads can be found on stones 3, 4 and 5. The dating of the images is difficult, but there are similarities to late Bronze Age weapons. Again, it is not easy to decide whether these representations were attached to the megaliths still in the manufacturing process or subsequently, possibly on work platforms built for this purpose.

Stonehenge 3 III

At a later point in the Bronze Age, the bluestones appear to have been erected again for the first time. However, the exact appearance of the site during this period is not yet clear.

Stonehenge 3 IV

In this phase, roughly between 2280 and 1930 BC BC, the bluestones were rearranged again. One part of them was integrated as a circle between the sarsen circle and the sarsen horseshoe and the other set up in the form of an oval around the center of the monument. Some archaeologists believe that an additional batch of bluestones would have to be brought in from Wales to complete this new building project. The altar stone could have been slightly relocated parallel to the erection of the oval, possibly away from the center to its current position (closer to the base, including the sarsen horseshoe). The work on the bluestones of this phase (3 IV) was carried out rather carelessly in comparison with the work on the sarsen in the previous phases. The bluestones that were initially removed and now set up again were poorly embedded in the ground, and some of them soon fell over again.

Stonehenge 3 V

Soon after, the northern part of the bluestone circle established in Phase 3 IV was removed, creating the arched formation we know today as the bluestone horseshoe. This structure mirrored that of the sarsen horseshoe, only that it was built from individually standing and considerably smaller, but almost twice as many stones: 19 compared to the 10 supporting stones of the sarsen horseshoe. This restructuring of the monument is dated from 2270 to 1930 BC. Dated. This phase (Stonehenge 3 V) thus runs parallel to that of Seahenge in Norfolk .

Stonehenge 3 VI

Around 1700 BC Two more rings of hole excavations were created just outside the Sarsen circle, in addition to the circle of Aubrey holes , which are located opposite on the inner periphery of the ring wall. The new circles are called the Y and Z holes (11 and 12). Their 30 or 29 holes were never filled with stones, otherwise soil compaction would have been found in them due to the pressure exerted by the stones. The Stonehenge monument appears on it from 1600 to 1400 BC. To have been given up, possibly in connection with the downfall or the suppression of the culture of its creators by a subsequent one. The holes filled up over the next few centuries, and the top layers of this material date from the Iron Age .

Alignment, proportion and symbolic character

The alignment was carried out in such a way that the sun rose directly over the heelstone on the morning of midsummer day , when it reached the furthest north-east in its course of the year, and sent its rays in the direction of the building. It is not known what significance the long shadow at the moment of sunrise that the heelstone threw on the altar stone, the base of the bluestones and sarsen horseshoes, among other things, on this occasion.

However, it is assumed with certainty that this architecture was by and large deliberately designed and implemented. The rising point of the sun at the turn of summer is directly dependent on the geographical latitude . In order to implement the orientation of the monument according to a plan, it must have been calculated or practically determined according to its position in this regard (51 ° 11 ′). This approach should therefore have been fundamental to the placement of the stones in at least some of the phases of Stonehenge. The heelstone and with it the symmetry axis of the horseshoe are therefore interpreted as part of a solar corridor that encompasses the rise of our daytime star.

Stonehenge could have served, among other things, to predict the summer and winter solstice and the spring and autumn equinox , and thus the seasonal turning points that are important for an arable culture.

According to research findings from a little earlier, the lunar course could be assigned a far greater role than previously assumed. For example, Gerald Hawkins published an article in Nature in 1963 called Stonehenge Decoded . Accordingly, the 19 megaliths of the bluestone horseshoe seem to be used to calculate the so-called Meton cycle , a period of around 19 years, during which the summer solstice and lunar eclipse fall on the same day. Since the latter event always includes the full moon and this in turn leads to particularly violent tidal currents , a correspondingly strong ebb can be expected for midday in the Avon .

The Neolithic circular system of Stonehenge, which dates back to the 1st phase around 3100 BC. The Aubrey holes on the outer edge have construction features and characteristics that, according to the computer scientist Friedel Herten and the geologist Georg Waldmann, indicate a lunisolar calendar . In their 2018 study, it is suggested that the Stonehenge lunisolar calendars and the Nebra Sky Disc were based on an 18.6 year cycle and relied solely on observing the movement of the northern lunar turns. With both systems, solar and lunar eclipses could have been predicted to the day more than 5000 years ago.

Urpolitik in the context of bluestones?

Roger Mercer has claimed that the bluestones are exceptionally finely worked. He postulated that they had once been brought to Stonehenge from an older monument in Pembrokeshire that had not yet been localized . Most other archaeologists agree that the bluestones were no less carefully worked than the sarsen stones. But if Mercer's considerations were correct, then the bluestones could have been transported away from that place in order to confirm a newly established alliance with the two sarsen formations based on their combination. This would not be countered by the interpretative approach according to which the bluestone structures in this alliance symbolize an inferior, therefore 'made small' enemy: The bluestones are, as I said, relatively tiny, almost dwarfs compared to the giants of the sarsen. Likewise, the change to the order suggested by Mercer in the sense of the dating outlined above (according to which the Bluestones were first in the Stonehenge area, then apparently, temporarily displaced by the Sarsen) would not fundamentally change the political character of his thesis.

In addition to this approach, some archaeologists have put an interpretation up for discussion, according to which the very hard eruptive material of the bluestones and the relative softness of the sarsen blocks made of sedimentary sandstone could symbolically stand for an alliance of two cultures or groups of people, each from the other Areas and therefore must have had different backgrounds.

New analyzes of contemporary burial sites nearby known as the Boscombe Bowmen have shown that at least some of the people who lived at the time of Stonehenge 3 may have come from what is now Wales. An analysis of the crystal polarization in the Bluestones has also shown that they can only have come from the Preseli Mountains .

Set-ups of bluestones resembling the little horseshoe from Stonehenge 3 IV have also been found at the sites known as Bedd Arthur in the Preseli Mountains and on the island of Skomer off the southwest coast of Pembrokeshire.

Techniques of edification and creation

Aubrey Burl claims that the bluestones were not transported here by humans alone, but at least part of the way through the Pleistocene glaciers from Wales. So far, however, no geological evidence of such a transport between the Preseli Mountains and Salisbury Plain has been found . In addition, no other specimens of this unusual dolerite stone have been found near Stonehenge.

There is much speculation about the methods of construction of the facility. If the bluestones did not change their places by glacier transport , as Aubrey Burl suspects, but were transported by human hands, there are many methods of moving huge stones with ropes and wood.

As part of an experiment in 2001, an attempt was made to transport a large stone along the suspected land and sea route from Wales to Stonehenge. Numerous volunteers pulled him across the country on a wooden sledge and then loaded him onto a replica of a historic boat. This soon sank together with the stone in rough seas in the Bristol Channel . A second experiment in August 2012, however, was successful and brought a bluestone by sea via the Bristol Channel and the Avon using Stone Age methods.

It has been suggested that A-shaped wooden frames, similar to a roof structure , were used to erect the stones and move them into a vertical position with ropes. The capstones could, for example, have been raised step by step with wooden platforms and then pushed up into place. Alternatively, they could have been pushed or pulled up into position via a ramp. The mortise and tenon joints on the stones suggest that the builders already had woodworking skills. Appropriate knowledge should have been of great help in the design and construction of this monument.

By Alexander Thom was opined that the builders of Stonehenge, the megalithic yard have used as the basis for various lengths.

The depictions of weapons engraved on the sarsen stones are unique in megalithic art in the British Isles. Elsewhere, abstract illustrations were preferred. Equally unusual for this culture is the horseshoe arrangement of the stones, as the stones were always arranged in circles elsewhere. The ax motif found, however, is comparable to the symbols in Brittany during this period. It is therefore likely that at least two construction phases of Stonehenge were built under significant continental influence. This would explain, among other things, the unusual structure of the monument.

There are estimates of the manpower required to build each phase of Stonehenge. The sums exceed several million man-hours . Stonehenge 1 believed to have taken about 11,000 hours of labor, Stonehenge 2 around 360,000, and the various parts of Stonehenge 3 could have taken up to 1.75 million hours of labor. The processing of the stones is estimated at around 20 million working hours, especially in view of the moderately powerful tools at this time. The general will to erect and maintain this building must therefore have been extremely strong and still required a strong social organization. In addition to the extremely complex organization of the construction project (planning, transport, processing and precise installation of the stones), this also requires a high overproduction of food for years in order to feed the actual “workers” while they are working on the project.

Reception and research history

First written mentions

The entire period from the archaeologically proven abandonment of Stonehenge at the end of the Bronze Age to the conquest of England by the Normans lies in historical darkness. Heinrich von Huntingdon was first mentioned by name around 1130 in his history of England ; in it he lists Stanenges in a short list of famous monuments in England. Geoffrey von Monmouth devotes himself to the stone circle in more detail in his History of the Kings of Britain , written around 1135 . He attributes the construction of the monument to the magician Merlin .

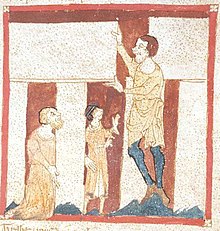

The first pictorial representations of the complex come from manuscripts from the 14th and 15th centuries. Relatively realistic pictorial representations have existed since the 16th century.

The historian Polydor Virgil (1470–1555) takes up Monmouth's description and also declares Stonehenge as a monument that the magician Merlin erected with the help of his magical powers at the time of the conquest of England by the Anglo-Saxons.

Theorizing since early modern times

Around 1580, the archaeologist William Lambarde ruled out a supernatural development of the complex for the first time by observing that carpentry techniques were transferred to the stone construction of Stonehenges when the stone circle was built. He is also the first to recognize that the stones were not brought in from Ireland by Merlin with the help of magic, as described earlier, but come from the Marlborough region.

The first book about Stonehenge appears in 1652. Its author, the builder Inigo Jones , who examined the complex in detail on behalf of the English king Jacob I , explains the stone circle as a Roman temple in honor of the god Coelus . In the following years, various other authors attempted to interpret the stone circle: The doctor Walter Charleton assumes in 1663 that Stonehenge was a coronation site for the Danish kings of England. The historian Aylett Sammes attributes the construction of the complex to the ancient Phoenicians in 1676.

At the end of the 17th century, the archaeologist John Aubrey (1626–1697) recognized the connection between Stonehenge and comparable monuments in Scotland and Wales and was the first to attribute the construction of all these facilities to real local builders. However, it is fatal for future research and the interpretation of the complex up to our time that Aubrey ascribes Stonehenge and all similar monuments on the British Isles to the Celts . His mistake becomes understandable from the scientific perspective at the end of the 17th century: There are no possibilities for dating prehistoric ground monuments; According to the biblical creation story, the age of the world is dated to a few thousand years, and the literature of ancient writers known to Aubrey contains no evidence of a pre-Celtic population of the British Isles. Aubrey can, however, take from the ancient Latin and Greek authors detailed descriptions of the druids as a Celtic priestly class and so he carefully suspects that the stone circles are the temple complexes of these same druids. In fact, there is more than 1,000 years between the abandonment of the facility at the end of the Bronze Age and the first appearance of so-called Celtic cultural features in Europe.

Eighteenth-century researchers take up Aubrey's thesis enthusiastically: The historian John Toland assigned Stonehenge to the Druids in his Critical History of Celtic Religion and Scholarship , written in 1719 . Between 1721 and 1724, the physician William Stukeley carried out the most detailed and precise measurements of the facility up to that point and was the first to suspect an axial alignment of the facility to the point of the summer solstice. In 1740 he summarized his results in a book and, using questionable and unscientific methods, interpreted Stonehenge as a druidic temple.

In his book The Geology of Scripture , Henry Browne , curator of Stonehenge since 1824 , interprets the stone circle as an antediluvian temple from Noah's time . He refers to the theories of the paleontologist William Buckland (1784-1856), who represents the theory of catastrophe or cataclysm instead of the theory of evolution .

First astronomical theories

At the beginning of the 20th century the astronomer Joseph Norman Lockyer (1836–1920) was the first to give a glimpse of a possible astronomical use of the facility . He suspects - like Stuckeley a century before him - that the system was oriented towards the point of the summer solstice, but speculates on the use of the stone circle as an astronomical calendar to determine holy Celtic festivals. Lockyer's theory was ignored by the archaeologists of his time, as his calculation bases were imprecise and, in some cases, arbitrarily selected by him in order to achieve the results he wanted. Stonehenge is therefore still “only” regarded by the archaeological experts as a prehistoric place of worship or consecration.

Astronomer Gerald Hawkins tried to change this picture when he published his book Stonehenge Decoded in 1965 . With the help of detailed measurements of the monument and complicated calculations, Hawkins wants to prove that Stonehenge served as a kind of stone-age computer with which its builders would have been able to predict lunar eclipses quite reliably, for example. Like John Aubrey's "Celtic thesis" at the time, Hawkins' theory is now being enthusiastically taken up by the general public. The professional world, on the other hand, tears up his research: The archaeologist Richard JC Atkinson , for example, proves that Hawkins also included parts of the facility in his evidence that verifiably existed or were built at different times and therefore cannot be part of the same facility.

Excavations and research

Modern exploration of Stonehenge began with the researcher William Cunnington (1754–1810). Cunnington's excavations and observations confirm the dating of Stonehenge to pre-Roman times. His research between 1812 and 1819 is published in the local history work Ancient History of Wiltshire by historian Richard Colt Hoare .

Around 1900, John Lubbock shows on the basis of bronze objects found in neighboring burial mounds that Stonehenge was already in use in the Bronze Age. William Gowland (1842–1922) restored parts of the complex and undertook the most careful excavations up to that point, which were completed in 1901. From his findings he concludes that at least parts of the monument were created at the time of the transition from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age. Archaeologist William Hawley excavated roughly half of the site between 1919 and 1926. However, his methods and reports are so inadequate that no new knowledge emerges. During this time, however, the geologist H. Thomas succeeded in proving that the bluestones were brought from South Wales by the builders of the facility .

1950 commissioned the Society of Antiquaries the archaeologists Richard Atkinson , Stuart Piggott and John Stone with further excavations. You will find many fireplaces and develop the division of the individual construction phases further, as it is still most often represented today.

Archaeologists Richard Atkinson and Stuart Piggott continued to dig in the second half of the 20th century. With the development and perfection of radiocarbon dating from the middle of the 20th century, it is now possible for the first time to reliably date the facility to the first half of the 2nd millennium BC. Atkinson and Piggott are also restoring other parts of the complex by erecting some of the overturned and tilted stones and setting them in concrete in the ground. These reconstructions are still limited to those stones that demonstrably only fell in modern times, or got in a lopsided position.

Much of the recent damage to the monument can be traced back to the earlier need of the surrounding population for stones on the one hand, and to the souvenir needs of previous visitors on the other. In the meantime, a blacksmith in the nearby town of Amesbury offered tourists a hammer that they could use to chop off bits of stones as souvenirs.

As part of the Stonehenge Riverside Project , archaeologists have been digging up the remains of a Neolithic village from 2600 to 2500 BC ( Grooved Ware ) in Durrington Walls since September 2006, 3.2 km from Stonehenge . “We think we've found the village of the builders of Stonehenge,” said Mike Parker Pearson , director of the excavation project at the University of Leeds , in January 2007 .

The first excavation in the stone circle since 1964 will take place from March 31 to April 11, 2008. Led by Timothy Darvill and Geoff Wainwright , a trench dug during the Hawley and Newall excavations in the 1920s is being reopened to look for organic material. With the help of mass spectrometry and radiocarbon dating, it is possible to determine the point in time at which the bluestones were erected to within a few decades.

In 2010, notable new discoveries will be made on the site. The application of modern technology indicates that there is much more to Stonehenge than just the world-famous circle of stone giants. The whole area, which covers many square kilometers, seems to be criss-crossed with places of worship and mysterious complexes. British researchers such as Vincent Gaffney from the University of Birmingham believe that no more than ten percent of what Stonehenge was and what it looked like in detail. A scientific examination of the site, which has just begun, has already discovered new circles - “ Timberhenge ” -, ditches and hills as well as carefully laid out walls and depressions.

Investigations in 2013 on the avenue leading from the River Avon to the southwest into the facility revealed that a meltwater channel had run here since the end of the Ice Age. Michael Parker Pearson of the University of Sheffield and Heather Sebire of English Heritage believe the builders of Stonehenge realized that the gully was pointing precisely in the direction of the winter solstice . This is how they explain the location of the prehistoric facility with this site feature found.

In September 2014 Vincent Gaffney from the University of Birmingham announced at the British Science Festival in Birmingham that based on the data collected over the past few years as part of the international Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes Project (since 2010 extensive surveys with ground penetrating radar and magnetometer ) On an area of 12 km² a first three-dimensional map with the traces of the as yet unexcavated finds was created. This includes 17 previously unknown wood and stone structures as well as dozen newly discovered burial mounds. It is now believed that Stonehenge was the center of scattered ritual monuments that expanded over time.

In November 2015, the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute (LBI) for Archaeological Prospection and Virtual Archeology (Vienna) reported the discovery of a 12-14 ° C warm spring 3 km away near Amesbury, which, because it does not freeze, is favorable for animals and thus could have been for hunters. Bones with stone arrowheads were found, and flint bulbs were found in an area of a spring pool.

Modern history

More recently, Stonehenge has been influenced by the close proximity of two busy roads (the main A303 between Amesbury and Winterbourne Stoke and the A344, which runs right past the monument). There were always various suggestions to relocate the streets or to tunnel them under. Since the 1950s, suggestions have been made to improve the situation for the protection of the facility and for visitors.

The Stonehenge complex was fenced in in 1901 and has only been accessible for an entrance fee since then. During the First World War, the Stonehenge Aerodrome , a field airfield , was built to the west in the immediate vicinity of the facility . After the war it was used as a depot for building materials and finally as a pig farm.

The flow of visitors increased massively after the Second World War. Parking spaces and toilets have been created opposite the stone circles on the other side of the A344. After repeated vandalism, the system had to be guarded around the clock. A hut was set up next to the parking lot for the guards. Since 1968, a tunnel under the A344 has connected parking spaces and the monument, a semi-underground building with a café and museum shop was built in it and expanded several times. The situation has been viewed as a national disgrace for decades. In 1978 additional fences were erected, since then visitors could no longer move freely between the stones, but had to stay on a path between the wall and the stone circles. Due to the never-ending rush of tourists, only the circumnavigation of the facility remained in the flow of visitors. It was hardly possible to linger for reflection in the memorable place.

Redesign since 2013

Since December 2013, the surroundings of Stonehenge and the access for visitors have been reorganized. The A344 road was abandoned in the section of the facility, the parking lots and the old visitor care facilities were demolished and renatured by mid-2014.

Instead, a visitor center with exhibitions and other offers was set up at a distance of around two kilometers from the stone circles. The buildings cannot be seen from the monument, so that a much more undisturbed experience is offered than before. Visitors can reach the stone circles from the museum on foot via a processional street or use a shuttle bus. The time on the road can and should be used to get in the mood with the help of an audio guide in many languages. Use of the shuttle bus and the audio guide are included in the entrance fee. Members (including temporary members) of the English Heritage receive free access. We recommend that you reserve in advance to visit the facilities. In the visitor center, an exhibition about the builders of Stonehenge, their culture and their history will be shown for the first time. It consists of a central video and five thematic information stations. The video shows the construction of the facility and the changing landscape as a result. The stations provide information on three levels of specialization. The exhibition is conceived together with the audio commentary and information boards in the area, all three media work together and complement each other. Outside the visitor center, huts and pits of the builders of Stonehenge have been reconstructed.

The way from the visitor center to the monument runs along the former road, about halfway through a small knoll the view of the complex opens up for the first time. The shuttles stop there for a moment and visitors have the choice of walking the rest of just under a kilometer in order to approach the stone circles independently, or to cover the rest of the way in the bus.

The new buildings were erected without foundations so as not to disturb any archaeological finds in the ground below.

New religious use

With the rediscovery and spread of classical literature, after the Renaissance there was an increasing interest in the druids mentioned in the ancient texts. Since the scientific exploration of prehistory was still in its infancy, Stonehenge was assigned to the Druids as a pre-Roman temple. This mistaken association is still influential. In 1781 the Englishman Henry Hurle founded a secret society called the Ancient Order of Druids . Although interest in druids waned in the mid-19th century, the religious orders that had emerged continued to exist. Their trips to Stonehenge always attracted onlookers. A striking example is the ceremony of the Ancient Order of Druids in August 1905, when 700 members of this order gathered in Stonehenge and solemnly accepted 256 candidates into their order. Today the modern druids form part of the new religious landscape, especially of Neopaganism . They meet regularly in Stonehenge and hold their ceremonies there.

On the summer solstice of 1972, Stonehenge hosted one of the free festivals popular in Great Britain at the time for the first time . This Stonehenge Free Festival has grown in popularity over the years; In 1984, an estimated 70,000 visitors met at the stone circle and celebrated the solstice with live music and various Druidic and neo-pagan cult acts. In 1985, in the run-up to the festival, there were violent conflicts between visitors and the police (battle of the beanfield) , whereupon the regulatory authorities banned the festival in Stonehenge and closed the area to all visitors, especially on the two solstices and the equinoxes.

In 1998, small groups of neo-pagans (including druids) were allowed back into the stone circle, and at the turn of the millennium, the Secular Order of Druids , citing the right to freely practice their religion, achieved that the ban on gathering for Stonehenge was lifted. In 2014, 36,000 people, tourists and devout druids, celebrated the beginning of the longest day of the year in Stonehenge the night before. The police arrested 25 people - mostly for drug offenses.

Esoteric

The amateur archaeologist Alfred Watkins (1855–1935) put forward a theory in the 1920s according to which the prehistoric megalithic structures - including Stonehenge - were connected by so-called ley lines , dead straight lines. Watkins, however, was thinking of real road connections. The author John Michell (born 1933) took up this thesis; In his book The View over Atlantis , published in 1969, he no longer interpreted the lines as paths, but instead brought the ley lines into connection with earth's magnetic force fields and “centers of force”.

This view quickly found numerous followers among the followers of esotericism up to our time. Michell's thesis should prove that the prehistoric builders of Stonehenge and comparable megalithic monuments still lived in perfect harmony with the cosmos and could sense such “lines of force” and “centers”, where they then built temples like Stonehenge, for example.

Documentary filmmaker Ronald P. Vaughan claims to have discovered a remarkable unit of measurement in the course of his research. The distance to the center of the neighboring stone circle of Avebury would correspond with 27,830 meters exactly to the 1440th part of the equatorial circumference (1: 1440 ≙ 1 minute: 1 day).

Reception in art and culture

Myths and legends

The heel stone was once known as Friar's Heel (English for ' monk's heel '). A legend that can be dated to the 17th century at the earliest tells the origin of the name:

“The devil bought the stones from a woman in Ireland and brought them to Salisbury Plain . One of the stones fell into the Avon , the rest it deposited in the plain. The devil shouted out loud, 'Nobody will find out how these stones got here.' A monk replied, 'Only you believe that!' Whereupon the devil threw one of the stones at him and hit him on the heel. The stone got stuck in the ground and that's how it got its name. "

Some believe that the name Friar's Heel is derived from Freya's He-ol or Freya Sul , named after the Germanic deity Freya and the (allegedly) Welsh words for "way" or "Sunday".

Stonehenge is often associated with the Arthurian legend . Geoffrey of Monmouth claims that Merlin brought Stonehenges from Ireland , where it was originally built on Mount Killaraus by giants who brought the stones from Africa. After his reconstruction at Amesbury, Geoffrey continues, they first got Ambrosius Aurelianus , then Uther Pendragon and later Constantine III. buried inside the ring. At many points in his Historia Regum Britanniae , Geoffrey mixes British legend with his own imagination. He associates Ambrosius Aurelianus with the prehistoric monument just because his name is similar to that of nearby Amesbury.

In modern times, pseudoscientists like Erich von Däniken have put forward the thesis that Stonehenge was built by extraterrestrial visitors to Earth.

literature

The first literary works related to Stonehenge emerged at the end of the 16th and beginning of the 17th centuries: During this time Edmund Spenser wrote his epic poem The Faerie Queene and Thomas Rowley wrote his drama The Birth of Merlin . Both works deal with the connection between the magician Merlin and Stonehenge and are largely inspired by Geoffrey von Monmouth's book History of the Kings of Britain . The poet John Dryden wrote a poem in the second half of the 17th century in which he pays homage to Stonehenge as the coronation site of Danish kings. In the 18th and 19th centuries, however, Stonehenge hardly played a role in non-scientific literature.

The novel Tess from the d'Urbervilles by Thomas Hardy (1840–1928) , published in 1891, is worth mentioning again . In this love story, Stonehenge plays a central, symbolic role. The novel was in 1979 by Roman Polanski with Nastassja Kinski in a Leading Role filmed and won three Oscars later; it was not shot on the original locations.

The non-scientific literature on Stonehenge in the 20th century is considerably richer and is mainly dominated by historical novels. From the now almost unmanageable number of publications, for example, the novel Pillar of the Sky by Cecelia Holland , the novel Die Druiden von Stonehenge by Wolfgang Hohlbein published in 1995 or the novel Stonehenge by Bernard Cornwell , published in Germany in 2001, should be mentioned . But also family sagas, horror, fantasy and even crime novels take up Stonehenge as a more or less dominant part of their plot. In his monumental work on life in the 1920s, John Cowper Powys combines Glastonbury Romance legends about the Holy Grail and the Arthurian myth in one episode with Stonehenge.

painting

Only three images of Stonehenge are known from the entire Middle Ages. The earliest drawings come from two manuscripts from the 14th and one manuscript from the 15th century.

The first of the three images shows the system in a panoramic view - but in perspective it is distorted into a rectangle; the second illustrates the construction of the complex by the magician Merlin and shows how he lifts one of the cap stones onto two bearing stones. The third illustration was rediscovered in 2007 and comes from the historical work Compilatio de Gestis , which was probably written around 1441. The text accompanying this illustration also refers to the construction of the complex by the magician Merlin .

The first realistic depiction was made by the Dutch artist Lucas de Heere (1534–1584) as a watercolor to illustrate his report Corte Beschryving van England, Scotland and Ireland, which was handwritten from 1573 to 1575 . The picture shows the stone circle from an elevated position from a north-westerly direction. The human figure in the center of the picture is leaning against the bearing stone No. 60. An engraving from 1575, signed only with the initials “RF”, and a watercolor by William Smith from 1588 in the manuscript Particular Description of England show the layout from a view similar to de Heere's watercolor. All three pictures are probably based on the same, unknown original. The engraving, signed only with "RF", was the model for a Stonehenge illustration in 1600 in the ancient book Britannia by William Canden (1551–1623). The illustration itself was the model for further pictures of Stonehenge.

The writings of the archaeologist John Aubrey (1626–1697) at the end of the 17th century, the research published on Stonehenge by the doctor William Stukeley in 1740 and the poems of Ossian by James Macpherson (1736–1796) influenced the artist in the course of the 18th century To interpret Stonehenge in her pictures as a Celtic or Druidic place of worship.

In 1797, the tallest of the still standing triliths fell inside the complex. For the artists, the problem arose of reproducing the structure and depth of the stone setting in their pictures. As a reaction to this, pictures from the 18th and 19th centuries now prefer to show the stone circle from a particularly deep perspective and depict the stones against the backdrop of a deep horizon. One of the most famous paintings that take this perspective is a watercolor by John Constables (1776–1837), who visited Stonehenge in 1820. Constable initially only made a sketch and then created a watercolor of the stone circle 15 years later. Other well-known pictures of Stonehenge were made by the English landscape painter William Turner (1775–1851). Around 1811 he drew a first view of the stone circle, which he later used as a template for a painting. Another picture was taken in 1828 and shows Stonehenge during a thunderstorm.

The painter and sculptor Henry Moore (1898–1986) created one of the most important recent works of art on Stonehenge in the 1970s with the Stonehenge album, which includes 16 lithographs .

music

- In his work Broken Circle for Sextet, the German composer Valentin Ruckebier makes several references to Stonehenge and the numerous theories and legends surrounding the ancient purpose of the stone circle.

- The progressive metal band Stonehenge from Hungary is named after the monument.

- From 1972 to 1984 the Stonehenge Free Festival music festival was held annually between the Stonehenge Stones and enjoyed great popularity with bands and audiences.

- Chris Evans and David Hanselmann released the concept album Stonehenge in 1980 , in which they linked various myths, including the Arthurian legend .

- The Norwegian comedian duo Ylvis asked in 2013 in the music video Stonehenge about the meaning of the building.

Replicas and derived names

- America's Stonehenge is an unusual stone circle formation near Salem , New Hampshire in the northeastern United States of America.

- When Mary Hill in the state of Washington was of Sam Hill with Maryhill Stonehenge a scale replica of Stonehenge built in the reconstructed original state as a war memorial. It is also aligned with the rise point of the midsummer sunrise. This was done using a virtual horizon instead of the currently visible position of the sun on the actual landscape horizon .

- Stonehenge inspired the geologist Jim Reinders for his work Carhenge (1987) or "Auto-Henge" at Alliance ( Nebraska ). He built the replica from gray-painted cars together with his family and dedicated it to his late father.

- In New Zealand in February 2005, Stonehenge Aotearoa was inaugurated, a functional replica that is used as a teaching aid for astronomical relationships and Maori culture.

Documentation

- The Stonehenge secret code. (OT: Stonehenge Decoded. ) Documentation and docu-drama , Great Britain, 2009, 43:32 min., Script and direction: Christopher Spencer, Colin Swash, production: National Geographic Channel, German first broadcast: December 13, 2009, series: Terra X . The film follows the excavations of a team led by Mike Parker Pearson ( University of Leeds ). Pearson was able to substantiate his thesis of a nationally significant place of worship for Stone Age clans who celebrated a rebirth there at the winter solstice with extensive finds in the area around the stone circle. However, the film claims that the extremely hard trilith stones were hewn exclusively with stones and not with iron, despite obvious and demonstrated finds from copper and goldsmith work.

- Stonehenge - The Ultimate Experiment. (OT: Mysterious Science: Rebuilding Stonehenge. ) Documentary and reconstruction, Great Britain, 2005, 78 min., Written and directed: Pati Marr, Johanna Schwartz, Bruce Hepton, production: National Geographic Channel, arte France, German first broadcast: December 2nd 2006, summary from arte, youtube.com

Quotes about Stonehenge

- How great! How wonderful! How incomprehensible! (engl. How grand How wonderful how incomprehensible! ) - Sir Richard Colt Hoare in Ancient History of Wiltshire (1812 to 1819)

- Much of what has been written about Stonehenge is made up, second-rate, or just plain wrong. ( Much of what has been written about Stonehenge is derivative, second-rate or plain wrong. ) - Christopher Chippindale

- Every age has the Stonehenge it deserves - or desires. ( Every age has the Stonehenge it deserves - or desires. ) - Jacquetta Hawkes

- Stonehenge, neither for disposition nor ornament, has anything admirable; but those huge rude masses of stone, set on end, and piled each on other, turn the mind on the immense force necessary for such a work. - Edmund Burke , in: "On the sublime and beautiful"

literature

- Stonehenge. In: Johann Heinrich Zedler : Large complete universal lexicon of all sciences and arts . Volume 40, Leipzig 1744, column 406 f.

- Karl Beinhauer (Ed.): Studies on Megalithics , (English edition: The Megalithic Phenomenon: Recent Research and Ethnoarchaeological Approaches ), 1999, ISBN 978-3-930036-36-3 .

- Barbara Bender et al .: Stonehenge. Making space. Oxford 1998.

- Aubrey Burl: Prehistoric Stone Circles. Shire, Aylesbury 1979, 1988, 2001, ISBN 0-85263-962-7 .

- Aubrey Burl: The Stonehenge People. London 1987.

- Rodney Castleden: The Making of Stonehenge. Routledge, London / New York 1993, ISBN 0-415-08513-6 .

- Christopher Chippindale: Who owns Stonehenge? Batsford, London 1990, ISBN 0-7134-6455-0 .

- Rosamund Cleal, KE Walker, R. Montague, Michael J. Allen (Eds.): Stonehenge in its landscape. Twentieth-century excavations. English Heritage, London 1995, ISBN 1-85074-605-2 ( digitized ).

- Barry Cunliffe , Colin Renfrew (Eds.): Science and Stonehenge. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1997, 1999, ISBN 0-19-726174-4 .

- Alex M. Gibson: Stonehenge & timber circles. Tempus, Stroud 1998, ISBN 0-7524-1402-X .

- Friedel Herten, Georg Waldmann: Functional principles of early time measurement at Stonehenge and Nebra . In: Archaeological Information . tape 41 , 2018, p. 275–288 , doi : 10.11588 / ai.2018.0.56947 ( PDF [accessed June 19, 2019]).

- Bernhard Maier : Stonehenge. Archeology, history, myth. Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-50877-4 (2nd edition 2018).

- Bernd Mühldorfer (Ed.): Mycenae - Nuremberg - Stonehenge. Trade and Exchange in the Bronze Age. (Treatises of the Natural History Society Nuremberg eV 43). VKA, Fürth 2000, ISSN 0077-6149 .

- John David North: Stonehenge. Ritual Origins and Astronomy , HarperCollins, London 1997, ISBN 0-00-255850-5 .

- Mike Parker Pearson: Stonehenge. Exploring the greatest Stone Age mystery, Simon & Schuster, London 2012, ISBN 978-0-85720-730-2 .

- Mike Pitts: Hengeworld. Arrow, London 2001, ISBN 0-09-927875-8 .

- Julian Richards: The Stonehenge Environs Project. London-Southampton 1990, ISBN 1-85074-269-3 ( digitized ).

- Julian Richards: Stonehenge. English Heritage, London 2005, ISBN 978-1-905624-92-8 .

- Wolfhard Schlosser , Jan Cierny: Stars and stones. A practical astronomy of the past. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1996, ISBN 3-534-11637-2 (from page 82ff. In detail on Stonehenge with good graphics and tables).

Web links

- Guide to Stonehenge from English Heritage

- Stonehenge dossier of the BBC with videos, theories etc.

- Stonehenge Dig 2008, BBC website on the excavations ( Memento of August 16, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- Supposed astronomical alignments at the monument on tivas.org.uk

- "A monumental waste" , Daily Telegraph , on the A303 near Stonehenge

- Stones of England - portal for British megalithic buildings

- Geneviève Lüscher : Stonehenge. Sanctuary in a cultic landscape. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung . December 24, 2012

Documentation and lectures

- Timothy Darvill : Great Riddles in Archeology: Merlin's Magic Circles. Stonehenge and the Preseli Bluestones

- State Office for Monument Preservation and Archeology Saxony-Anhalt : Harald Meller meets… Timothy Darvill

photos

- Stonehenge Laser Scans (English)

- Information and images of Stonehenge on Modern Antiquarian (English)

- Tate Online: British and international modern and contemporary art Overview of the collection of artworks with Stonehenge as a theme in the Tate Gallery (English)

- Stonehenge at sunrise , QuickTime Virtual Reality

- Stonehenge 360 ° panorama on the BBC's Wiltshire website

Individual evidence

- ↑ Entry “Stonehenge” in the Duden .

- ^ EJ de Meester: Did Atlantis lay in England? August 12, 2007, see third graphic , accessed on April 2, 2020 (English).

- ↑ RS Thorpe & O. Williams-Torpe: The myth of long-distance megalith transport . Ed .: In Antiquity. 1991.

- ↑ Angelika Franz: New dating: Stonehenge is probably older than previously assumed . In: Spiegel Online , October 9, 2008, accessed September 11, 2014.

- ^ C. Gaffney, Vince Gaffney, W. Neubauer et al .: The Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes Project. In: Archaeological Prospection. Volume 19, No. 2, April – June 2012, pp. 147–155.

- ↑ Ludwig Boltzmann Institute: The “Stonehenge Hidden Landscape Project” - Results On: lbi-archpro.org from 2014, last accessed on September 11, 2014.

- ↑ Stonehenge; henge 2 . In: Oxford English Dictionary , 2nd edition, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1989.

- ↑ Christopher Chippindale: Stonehenge Complete. Third revised edition, Thames & Hudson, London 2004, ISBN 978-0-500-28467-4 .

- ↑ Stonehenge - a burial place 5000 years ago? Stone circle built later . From: nzz.ch , May 29, 2008, accessed on September 11, 2014.

- ↑ a b Colin Renfrew: The megalithic cultures . Ed .: Spectrum of Sciences.

- ↑ Revealed: Early Bronze Age carvings suggest Stonehenge was a huge prehistoric art gallery . In: The Independent v. October 9, 2012; Stonehenge up close: digital laser scan reveals secrets of the past . In: The Guardian v. October 9, 2012.

- ↑ a b Timothy Darvill, Peter Marshall et al .: Stonehenge remodeled . In: Antiquity. Volume 86, No. 334, December 2012, pp. 1021-1040 [1021f.]

- ↑ a b c Guardian: Stonehenge was built on solstice axis, dig confirms . On: theguardian.com on September 8, 2013, last accessed on September 11, 2014.

- ^ Scientists solve mystery of the origin of Stonehenge megaliths. In: Reuters. July 29, 2020, accessed on August 4, 2020 .

- ↑ A horseshoe as a lunar computer. Stonehenge as an astronomical forecasting tool? On: scinexx.de from February 1, 2008, last accessed on September 11, 2014.

- ↑ Friedel Herten, Georg Waldmann: Functional principles of early time measurement at Stonehenge and Nebra . In: Archaeological Information . tape 41 , 2018, p. 275–288 , doi : 10.11588 / ai.2018.0.56947 ( uni-heidelberg.de [PDF; accessed on June 19, 2019]).

- ^ RS Thorpe and O. Williams-Torpe: The myth of long-distance megalith transport. In: Antiquity 65, 1991.

- ^ Stonehenge News and Information , accessed November 8, 2017.

- ↑ Prof. Christopher Witcombe: Stonehenge

- ^ Stonehenge and Neighboring Monuments. New Edition with Revisions in Interpretation and Dating. Reprint of the 1703 edition printed in London by E. Powell. Published by English Heritage ; edited by Ken Osborne. St. Ives Westerham Press 2002, pp. 17f.

- ↑ Archaeologists find the builders' village - A Stonehenge puzzle seems to have been solved. In: RP Online . July 31, 2007, accessed June 21, 2011 .

- ↑ In: Science . Vol. 320, p. 159 of April 11, 2008.

- ↑ Peter Nonnenmacher: Stonehenge: Stone Age Cinderella - Stonehenge the funds for a visitor center are canceled. On: Badische Zeitung.de of September 3, 2010.

- ↑ Nishad Karim, Aditee Mitra (British Science Association Media Fellows): Unraveling the mysteries of Stonehenge ( Memento of September 11, 2014 Internet Archive ). On: britishscienceassociation.org September 2014.

- ^ University of Birmingham : New digital map reveals stunning hidden archeology of Stonehenge . On: birmingham.ac.uk of September 10, 2014.

- ↑ Maria Dasi Espuig: Stonehenge secrets revealed by underground map . On: bbc.com of September 10, 2014.

- ↑ Stonehenge: Warm springs and pink flints ( science.orf.at ), November 4, 2015, accessed November 4, 2015.

- ↑ Michael Hohla, Rupert Lenzenweger: A shadowy existence - the conspicuous crusty red alga (Hildenbrandia rivularis) in Upper Austria. In: Natural history station of the city of Linz (ed.): ÖKO.L magazine for ecology, nature and environmental protection. Volume 34, Issue 3, Linz 2012, pp. 3–12 ( PDF on ZOBODAT , also flora-deutschlands.de , accessed November 4, 2015).

- ↑ Troubled Stonehenge 'lacks magic' . In: The Independent . 2006. Retrieved April 11, 2009.

- ↑ The description of the visitor facilities since 2013 follows: Christopher Chippingdale, Chris Gosden, et al .: New era for Stonehenge. In: Antiquity. Volume 88, 2014, pp. 644-657.

- ↑ english-heritage.org.uk

- ↑ english-heritage.org.uk

- ↑ ORF: Tens of thousands celebrate the solstice in Stonehenge , June 21, 2014.

- ↑ Ronald P. Vaughan: Genius and Geometry - Stonehenge and Measuring the World. 3sat, 2010, accessed January 29, 2013 .

- ^ Christian Heck: A new Medieval view of Stonehenge. ( Memento of December 6, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) In: British Archeology. 92, January / February 2007 or redicecreations.com

- ^ Henry Moore from Stonehenge, Stonehenge III 1973 , Tate Gallery

- ↑ Valentin Ruckebier: Valentin Ruckebier - Broken Circle. January 20, 2017. Retrieved May 25, 2017 .

- ↑ Ylvis: Stonehenge on YouTube , accessed April 6, 2018.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ C. Chippindale: Stonehenge Complete. London 2004. (page?)

- ↑ Jacquetta Hawkes: God in the Machine. In: Antiquity. Volume 41, No.?, 1967, pp. 174-180, here 174a.

- ↑ Bartleby - "Encyclopedia, Dictionary, Thesaurus and hundreds more.": Edmund Burke (1729–1797). On the sublime and beautiful. The Harvard Classics. 1909-14. «Difficulty» on: bartleby.com ; last accessed on September 11, 2014.