Konrad Grebel

Konrad Grebel (* around 1498 in Grüningen / Switzerland ; † August (?) 1526 in Maienfeld near Chur) was the son of a well-known Zurich merchant and councilor . He is considered a co-founder of the Anabaptist movement and is often referred to as the Anabaptist father.

Beginnings

Konrad Grebel was born in Grüningen as the son of Bailiff Hans Jakob Grebel (around 1460–1526) and his wife Dorothea, daughter of Hans Fries, Ammann von Uri. The family on his father's side had belonged to the Meisen guild for generations . His father was a member of the Small Council , and from 1521 to 1525 about 30 times Tagsatzung envoy . He was open to the Reformation, but at the same time was an opponent of Zwingli. In 1526 Hans Jakob Grebel was probably wrongly executed. Allegedly, he had disregarded the 1522 ban on accepting foreign pension funds.

Konrad was the second of six children. He spent his youth in Grüningen Castle , to which he was to return as a prisoner in 1525. In 1511 he moved with his family to Zurich , where he attended the Carolina Latin School belonging to the Grossmünster . Then studied from 1514 to 1515 in Basel under Glarean , from 1515 to 1518 in Vienna under Vadian and from 1518 to 1520 Paris again under Glarean. However, he never achieved a university degree. During this time, Konrad Grebel began extensive correspondence with contemporary philosophers with a humanistic character. Among them was above all Joachim von Watt (called Vadian ), his teacher at the University of Vienna and later brother-in-law. A total of 56 letters from Grebel to him have survived.

After Grebel's father had received news about his son's relaxed student life in Paris, he canceled the financial support and ordered Konrad back to Zurich around 1521. For a time he worked as a lecturer at Andreas Cratander in Basel, but returned to Zurich after only two months. He made contact with a group that had formed around the Swiss reformer Huldrych Zwingli . He and his cousin Leopold had already been contacted by Zwingli during their studies in Vienna. In this reading group, also known as sodality , the Vulgate as well as the Hebrew scriptures of the Old and the Greek scripts of the New Testament were studied in addition to the Greek classics . It was here that Grebel met Felix Manz , who later became the Baptist , with whom he soon developed a deep friendship.

On February 6, 1522, Konrad married Grebel. His wife Barbara (her family name is unknown) was probably a novice at the Dominican monastery in Oetenbach , where a sister of Grebel lived as a nun . Barbara was already pregnant at the time of the marriage. The marriage had three children: Theophil (1522), Joshua (1523) and Rachel (1525). Although Grebel's parents reacted with displeasure at the wedding, they still took the young couple into their home. A letter to Vadian shows that the young family lived in Konrad Grebel's parental home until 1524.

Grebel and Zwingli

In the spring of 1522 Konrad Grebel experienced the decisive turning point towards the gospel preached by Zwingli and actively and publicly advocated the Reformation . With like-minded people he participated in provocation of the Old Believers by means of preaching disorders. This meant that he in July 1522 together with Klaus Hottinger and the two bakers Bartlime Pure and Heinrich Aberli before the Council was quoted, where he called one of the council members as a devil. Grebel, for his part, urged the council not to hinder the evangelical movement any further. One consequence of the provocations was the convocation of the First Zurich Disputation in January 1523, where the scriptural sermon was declared the norm in Zurich's territory. When, as a result, Reformation circles in rural communities in Zurich raised the tithing question and openly broke with the veneration of saints and the celebration of mass , Grebel and other radical Zwingli students sided with them. Grebel also unreservedly supported the iconoclastic actions that had been carried out in the city of Zurich and the surrounding communities since autumn 1523. In this troubled situation, the council called a second disputation to publicly discuss the church decorations and the mass . At this Second Zurich Disputation in October 1523, the theological justification for the abolition of the mass and the removal of the pictures from the churches from the Bible was given . Zwingli, however, left it to the council to determine the time and the procedure for the establishment of the new order. Grebel and Simon Stumpf resolutely objected to Zwingli giving the authorities such powers in religious matters. The split between Zwingli and the Grebelkreis, which had already been announced in the tenth question, now became evident.

New understanding of baptism

In a time of self-reflection, Grebel now checked his position. In 1524 he held Bible studies on the Gospel of Matthew in the Castelberg reading group , put together a Bible concordance on the topics of faith and baptism , and contacted other reformers by letter such as Martin Luther , Andreas Bodenstein von Karlstadt and Thomas Müntzer . Karlstadt initially sent his friend Gerhard Westerburg with some of his tracts to the Proto-Anabaptists in Zurich; in the fall of 1524 he even traveled to join them himself. However, an agreement with him was not reached. In September and October Konrad Grebel and his friends wrote two letters to Müntzer in which they expressed their sympathy and solidarity, but also some criticism. Points raised were the doctrine of the sacrament , the tithing question, non-violence and the liturgical reform . The common rejection of infant baptism was of central importance.

Since the spring of 1524, when Wilhelm Reublin and Johannes Brötli openly called in their congregations to refuse infant baptism , the new understanding of baptism had become a central point in the dispute with Zwingli. Grebel and Manz publicly questioned the biblical justification of infant baptism and demanded a disputation from the city council on the baptism issue. Zwingli's first baptism disputation in Zurich on January 17, 1525 ended with a resounding success. The Zurich Council issued a mandate in which all those who refused to be baptized were asked to have their newborn children baptized immediately. Anyone who does not comply with this request within eight days will be expelled from the country. Grebel himself was affected by this verdict because he had not baptized his daughter Rachel, who was born on January 6, 1525. In a second mandate from January 21, 1525, Grebel and Manz were forbidden from any further agitation against infant baptism and teaching in their Bible schools ( special schools ) was forbidden. The non- Zurich Anabaptists (Reublin, Brötli, Castelberger and Hätzer ) were asked to leave the Zurich area within eight days.

First baptism of believers

Disappointed about the outcome of the baptism disputation and probably desperate about the threat of breaking up their circle, some of the opponents affected by child baptism probably met for a meeting in the house of the Manz family on the evening when the mandate was issued. The first known baptism of believers took place on the occasion of the meeting of the radical reading group . According to his own statements, it was Jörg Blaurock who asked Konrad Grebel to carry out the baptism. In a simple ceremony, Grebel baptized the former priest with a kitchen ladle , who in turn baptized the rest of the congregation.

The report of this first baptism clearly bears traits of a founding myth and only appeared years later in the history book of the Hutterite Brothers . The chronicle reports that "fear began and came upon them" and "that their hearts were afflicted". Blaurock kneeled down and asked to be baptized "into his faith and knowledge". There are different interpretations of this event. They range from the planned establishment of the first Anabaptist congregation to the spontaneous provocation of the authorities. Zwingli interpreted this first "re-baptism" as a conscious act of separation. In fact, the subject of "repetition of baptism" had never been addressed in Grebel's letters and had not previously been the subject of government mandates.

Missionary activity

In the week after January 21, 1525, there was lively Anabaptist missionary activity in Zollikon . Grebel held a sacrament service there in a private house on January 22nd or 23rd. Unlike Brötli, Manz, Blaurock and others, however, he does not seem to have carried out any adult baptisms in Zollikon himself. Since he did not want to submit to the council mandate, he evaded to Schaffhausen , where he met with the reformer Sebastian Hofmeister . From here he stayed in contact with Reublin and Brötli, who had also fled to northeastern Switzerland. He also stayed in touch with Balthasar Hubmeier , who was actually carrying out an Anabaptist Reformation in Waldshut during this time.

Grebel's further paths cannot be precisely followed. His presence in St. Gallen is documented around Easter 1525 . Together with Wolfgang Ulimann , Hans Krüsi and Lorenz Hochrütiner , he was responsible for the widespread dissemination of Anabaptist ideas. According to the contemporary chronicler Fridolin Safe , Grebel is said to have baptized around three hundred people in the Sitter outside the city of St. Gallen. After his letter on the question of baptism was read out in public in the city, he was forced to leave St. Gallen. This was also the final break with his fatherly friend Vadian.

After a short return to Zurich, where he managed his affairs and tried in vain to get his wife to accompany him, he began preaching in the Zurich Oberland in the summer of 1525 . At that time, a real peasant revolt was going on in the Grüninger office . Grebel and the other Anabaptist preachers, to whom Manz and Blaurock had also joined, found an attentive audience. With their Anabaptist message, they heated up the anti-clerical and anti-nobility sentiment considerably and were very popular.

Captivity and death

On October 8, 1525, Grebel was arrested together with Blaurock and imprisoned in Grüninger Castle, the place where he was born. The two were then transferred to prison in Zurich. At the request of the Grüninger Landvogts Jörg Berger, a third baptismal disposition was carried out from November 6th to 8th, in which Felix Manz, who was arrested again, also took part. Due to the large number of people, the event had to be moved from the town hall to the Grossmünster . After the disputation, which was more like a court hearing, the three Anabaptist leaders were thrown into the New Tower on November 18, 1525 with bread and water for an indefinite period ( as long as God was content and my gentlemen well covered ) . At the beginning of March 1526, the prisoners were interrogated again. The sentence has now been set to life imprisonment. In addition, the council decided to punish rebaptism with drowning in the future . Two weeks later, on March 21, 1526, the captured Anabaptists managed to escape from prison.

After fleeing to Appenzell and Graubünden , Konrad Grebel turned to continue promoting the Anabaptist concerns. However, he was soon overtaken by the plague . He was able to make his way to Maienfeld , where he died in the summer of 1526 in the house of his sister Barbara. How and where he was buried is not known.

Work and appreciation

About 70 letters from Grebel have survived between 1517 and 1525. Most of these are addressed to Vadian and date from his student days. The petition to the Zurich Council, the protestation and protective letter , which was previously attributed to him, comes from Felix Manz. On the other hand, the two letters that were addressed to Müntzer by the Anabaptists were written by Grebel himself. He never seems to have completed a script he had planned on the question of baptism. The Bible Concordance, which appeared in Augsburg in 1525 under the name of Hans Krüsi, may have come from Grebel.

His actual Anabaptist ministry only lasted a year and a half. Since he was the first known believer to be baptized during the Reformation, he was and is also called the Anabaptist Father in free church and Anabaptist circles .

Zwingli saw only minor differences between his and Grebel's reformatory ideas. However, his replies make it clear that he did not understand Grebel's real concern: freedom of conscience and the separation of church and state . The Zurich Anabaptist congregation under Grebels and Manz's leadership were thus the avant-garde of an idea that would only take hold in Europe centuries later.

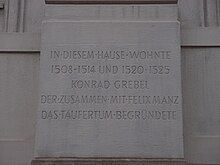

On the occasion of the Mennonite World Conference in 1952 in Basel, a memorial plaque for Konrad Grebel was set up at his parents' house on Neumarkt in Zurich. The board contains the following text: In this house lived 1508–1514 and 1520–1525 Konrad Grebel, who founded the Anabaptism together with Felix Manz.

The Conrad Grebel University College, which belongs to the University of Waterloo in Ontario , Canada, is named after Grebel .

literature

- Friedrich Wilhelm Bautz : Grebel, Konrad. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 2, Bautz, Hamm 1990, ISBN 3-88309-032-8 , Sp. 295-296. * Harold S. Bender: Conrad Grebel, approx. 1498–1526. The Founder of the Swiss Brethren, Sometimes called Anabaptists . Goshen 1950.

- Heinold Fast : Konrad Grebel: the will on the cross. In: Hans-Jürgen Goertz (ed.): Radical Reformers. Munich 1978, ISBN 3-406-06783-2 , pp. 103-114.

- Heinold Fast: Grebel, Konrad. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 7, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1966, ISBN 3-428-00188-5 , p. 15 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Hans-Jürgen Goertz : Konrad Grebel. Critic of the pious appearance. 1498-1526. A biographical sketch. Bolanden / Hamburg 1998, ISBN 3-930435-21-7 .

- Hans-Jürgen Goertz: Konrad Grebel - a radical in the Zurich Reformation. Zurich 2004, ISBN 3-290-17317-8 .

- Peter Hoover: Baptism by Fire. The radical life of the Anabaptists - a provocation. Down to Earth, Berlin 2006, ISBN 978-3-935992-23-7 , Konrad Grebel on pp. 16-19 and 31-35.

- Diether Götz Lichdi: Konrad Grebel and the early Anabaptist movement. Location 1998, ISBN 3-927767-70-0 .

- Andrea Strübind : More zealous than Zwingli. The early Anabaptist movement in Switzerland. Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-428-10653-9 .

- Meyer von Knonau : Grebel, Konrad . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 9, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1879, pp. 619-622.

Web links

- Literature by and about Konrad Grebel in the catalog of the German National Library

- Hans-Jürgen Goertz: Grebel, Konrad. In: Mennonite Lexicon . Volume 5 (MennLex 5).

- Ulrich J. Gerber: Konrad Grebel. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Harold S. Bender, Leland D. Harder: Grebel, Conrad (approx. 1498-1526) . In: Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online

Individual evidence

- ↑ Dieter Götz Lichdi: The Mennonites in the past and present. From the Anabaptist Movement to the Worldwide Free Church , Großburgwedel 191983, p. 26.

- ^ Family tree of Jakob Grebel. Retrieved October 9, 2019 .

- ^ Heinold Fast: Grebel, Konrad. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 7, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1966, ISBN 3-428-00188-5 , p. 15 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ↑ Goertz (1998), p. 22.

- ↑ Goertz (2004), p. 14f.

- ^ Emil Arbenz, Hermann Wartmann (ed.): Vadian letter collection of the St. Gallen city library . Vol. I-VII, St. Gallen 1888–1905.

- ↑ Zwingli's letter is no longer preserved, but Grebel's answer of September 8, 1517 is. Emil Egli (Ed.): Huldreich Zwingli's complete works , Vol. VII. Leipzig 1911, No. 27.

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Goertz (2004), p. 26.

- ↑ Fast (1978), p. 106.

- ↑ Goertz (1998), p. 51.

- ↑ Goertz (1998), p. 64ff.

- ↑ Goertz (1998), pp. 73f.

- ↑ See Strübind (2004), The Disputation of January 1525. pp. 337–351.

- ↑ Goertz (1998), p. 109.

- ↑ Strübind (2004), p. 352.

- ^ Fritz Blanke: Brothers in Christ. The history of the oldest Anabaptist community . Zurich 1955.

- ↑ Goertz (1998), p. 113.

- ↑ Peter Hoover: Baptism of Fire. The radical life of the Anabaptists - a provocation , Down to Earth, Berlin 2006, ISBN 978-3-935992-23-7 , pp. 16-19

- ↑ Goertz (1998), p. 115.

- ↑ Goertz (1998), pp. 199ff.

- ↑ Goertz (1998), p. 118.

- ↑ Heinold Fast: Hans Krüsis little book about faith and baptism. An Anabaptist print from 1525. In: Zwingliana. 11/1 (1962), pp. 456-475.

- ↑ Hanspeter Jecker: Dialogue, conversation and steps towards reconciliation between Anabaptist-Mennonite congregations and Evangelical-Reformed churches (PDF; 37 kB)

- ^ Conrad Grebel University College

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Grebel, Konrad |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Co-founder of the Anabaptist movement |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1498 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Grüningen |

| DATE OF DEATH | after March 1526 |

| Place of death | Maienfeld |