Henry III. (HRR)

Henry III. (* October 28, 1016 or 1017; † October 5, 1056 in Bodfeld , Harz ) from the Salier family was king from 1039 until his death in 1056 and since 1046 emperor in the Roman-German Empire .

At a young age, Heinrich was raised to the rank of co-king by his father Konrad II in 1028 and endowed with the duchies of Bavaria and Swabia . In contrast to other changes of power in the Ottonian-Salian times, the transition of royal rule after the death of his father took place smoothly and Heinrich continued the policy of his predecessor in the given channels. His term of office led to a hitherto unknown sacred exaggeration of the royal rule. During Heinrich's reign, the Speyer Cathedral was expanded to become the largest church in Western Christendom at the time. In relation to the dukes, Heinrich enforced his view of the legally established power of disposal over the duchies and thus secured their control. In Lorraine this led to years of conflict, from which Heinrich emerged victorious. But a powerful opposition group also formed in southern Germany between 1052 and 1055. In 1046 Heinrich ended the papal schism , freed the papacy from its dependence on the Roman nobility and laid the foundation for its universal validity. For a long time his reign was seen as the high point of medieval imperial rule and his early death was viewed as a catastrophe for the empire. More recent contributions, however, speak of the beginning of a crisis in the Salian monarchy in the later years of his reign.

Life until assumption of power

Origin and family

Heinrich was probably born in 1016 rather than 1017 as the son of Conrad the Elder, later Emperor Conrad II, and Giselas of Swabia . Heinrich's younger sisters Beatrix (approx. 1020-1036) and Mathilde (after mid-year 1025 – beginning 1034) remained unmarried and died early. Heinrich's father came from an aristocratic family from the Rhineland-Franconia, whose property and count's rights had been in the area around Worms and Speyer for generations ; In addition, Konrad was the great-grandson of Konrad the Red, who died in the battle against the Hungarians in 955 on the Lechfeld, and was related to the Ottonians through his wife Liutgard . Heinrich's mother Gisela was widowed twice. Her father Hermann von Schwaben had unsuccessfully asserted his own claims in the king's election in 1002. Gisela's mother Gerberga was a daughter of the Burgundian King Konrad and a granddaughter of the West Franconian Carolingian ruler Ludwig IV. Heinrich's birth falls into a difficult situation for the Salian family. Konrad had only been involved in a bloody feud two months earlier and could only rely on the support of friends and relatives. The relationship with Heinrich II was strained for Konrad because of his marriage to Gisela von Schwaben, which some contemporaries rejected as a marriage of relatives . Konrad lost the imperial grace and it seemed at first that Konrad could not even become a duke.

Consolidation of the dynasty and securing of the succession

After the death of Henry II, the last male representative of the Ottonian dynasty, Konrad was able to assert himself as ruler at a gathering of the great in Kamba in 1024 . In addition to Konrad's descent from Otto I - which he shared with his competitor Konrad the Younger - the character traits virtus and probitas (efficiency and righteousness) that earned Konrad widespread approval. As the first Salic ruler, Konrad systematically built up his son Heinrich as his successor. Bishop Brun of Augsburg and from around May 1029 to July 1033 Bishop Egilbert von Freising took care of Heinrich's education. Certainly the Kapellan and historiographer Wipo also participated in the upbringing at times.

Heinrich received a good education at the court of the Augsburg bishop Brun. As the brother of Emperor Heinrich II, he was certainly the right person to convey ruling traditions and imperial ideas to the heir to the throne. At the beginning of 1026 Konrad moved from Aachen via Trier to Augsburg , where the army gathered for the Italian campaign . For the period of the ruler's absence, Heinrich was entrusted to the " tutela " (tutela) of Bruns. Already at this time Konrad arranged the succession. With the consent of the princes, he appointed his son Heinrich as his successor in the event of his death. After Konrad's return from Italy, he transferred the Duchy of Bavaria, which had been vacant since February 1026, to his son in Regensburg on June 24, 1027 due to the death of Henry V. The award of the duchy to a not yet ten-year-old king's son who was not from Bavaria was unprecedented. In 1038, a year before Konrad's death, Heinrich also took over the Swabian duchy.

As early as February 1028, Heinrich's interventions contained the addition "only son" in his father's diplomas . The royal dignity was transferred on a court day in Aachen for Easter in 1028. With the consent of the princes and the 'people', Heinrich was made king and consecrated by Archbishop Pilgrim of Cologne . A few months later Konrad's first imperial bull shows the image of the emperor's son with the inscription Heinricus spes imperii (Heinrich, hope of the empire) on a diploma dated August 23, 1028 for the Gernrode Abbey . Heinrich's emphasis on the bull with the reference to the empire, whose crown he will one day wear, carefully suggests the idea of co-emperorship.

The firm anchoring of royal rule and empire in his house intended by Konrad went even further. In the spring of 1028 an embassy went to the imperial court in Byzantium . Following the Ottonian tradition, Konrad first looked for a Byzantine emperor's daughter for Heinrich. Only after this plan failed, Heinrich was betrothed to Gunhild , the daughter of the Anglo-Scandinavian King Canute the Great , at Whitsun 1035 at the Bamberg Court Day . A year later, again at Pentecost, the wedding took place in Nijmegen .

In 1027 Konrad met the childless King Rudolf of Burgundy near Basel to arrange the transfer of the Kingdom of Burgundy after Rudolf's death. It may also have been determined that Heinrich should enter into the contract in the event of the untimely death of his father. After two large-scale campaigns against his adversary Odo von der Champagne , Konrad completed the acquisition of Burgundy in a demonstrative coronation act on August 1, 1034. This marked the beginning of the time of the “Trias of Empires” (tria regna) , that is, when the royal rule in Germany, Italy and Burgundy was combined to form an empire under the rule of the German king and emperor. In autumn 1038 Konrad II held court in Solothurn . He transferred the Regnum Burgundiae to his heir to the throne. The act of homage served above all to secure the succession of the young Salier in a newly acquired domain. With the election, homage and acclamation by the Burgundians, the Salians were able to show that the rule came to them by hereditary path and not through an act of violence. In 1038 Heinrich stayed in Italy with his father. On their return, Heinrich's first wife Gunhild, who had recently given birth to their daughter Beatrix , died.

Although Heinrich was legally a king, he had to become familiar with the practice of rulership over time. The first independent act is a peace treaty with the Hungarians from 1031. This was the consequence of a failed advance by Konrad II the previous year and resulted in territorial losses between Fischa and Leitha . In 1033 Heinrich successfully carried out a military campaign against Udalrich of Bohemia .

Even against the will of his father, he was able to maintain an independent position. When Konrad tried to overthrow Duke Adalbero of Carinthia in 1035, Heinrich refused to support him. It was only when Konrad threw himself at his son's feet in tears and pleaded not to disgrace the empire that Heinrich gave up his resistance. Heinrich justified himself by pointing out that he had sworn an oath to Adalbero.

When Konrad died in Utrecht in 1039 , this meant no danger to the kingdom and the kingdom. The transfer of power was the only safe change of the throne in Ottonian-Salian history. Henry III. had been prepared by his father for his future duties as king through the designation , the elevation to Duke of Bavaria, the coronation of the king in Aachen, the transfer of the Duchy of Swabia and the acquisition of Burgundy for the independent royal rule. Heinrich and his mother took the corpse of his father with the court entourage to Cologne and from there via Mainz and Worms to Speyer . According to Wipo, he showed his “humiliating devotion” by “lifting the body on his shoulders at all church portals and, most recently, at the burial of his father”. He gave support to his father's soul through funeral services and memorial services . Konrad was buried with high honors in the Speyer Cathedral . Concern for the salvation of his father's soul motivated Heinrich to make numerous donations. On May 21, 1044, Heinrich made an important foundation for the salvation of his father's soul in the Utrecht Cathedral . Heinrich made it mandatory for the canons of the Aachen Marienstift to celebrate the anniversary of his father's death and that of his wife Gunhild, who died in 1038, with mass ceremonies and extended night-time officers every year.

Royal and Imperial rule

Assumption of power

The change of government took place without any difficulties. Only Gozelo von Lorraine is reported to have initially considered refusing to pay homage. However, his attitude did not lead to serious conflict. Although Heinrich was already co-king, the usual formalities were carried out after his father's death. A throne was placed in Aachen and homage is also reported. However, a tour to gain and recognize power, as was the case under Heinrich II and Konrad II, did not take place. However, Heinrich visited all parts of the empire in 1039/40 and undertook governmental acts. Unlike at the beginning of his father's reign in 1024, there was no unrest or opposition in Italy when Heinrich came to power. The conflict between Archbishop Aribert of Milan and his father Konrad was quickly resolved by Heinrich after Aribert submitted to a court day in Ingelheim in 1040 and paid homage to the king.

After the death of his first wife Gunhild, it was five years before Heinrich decided to enter into a new marriage. The offer of Grand Duke Yaroslav I of Kiev to give him his daughter as his wife remained in vain . In the summer of 1043 Heinrich wooed Agnes von Poitou , a daughter of Duke Wilhelm V of Aquitaine . The advertisement was successfully presented by Bishop Bruno von Würzburg . After the engagement in Besançon in Burgundy , the coronation as queen took place in Mainz. The solemn wedding took place in Ingelheim at the end of November 1043 . Strictly ecclesiastical circles raised concerns about this marriage, because the bride and groom were too closely related to each other as descendants of Henry I according to canon law . This marriage should serve to further secure the German rule in Burgundy, because the grandfather of the bride was Count Otto Wilhelm , who at the time of Heinrich II. The legacy of Rudolf III. had fought most of Burgundy .

Conflicts with Bohemia and Hungary

In his early years Heinrich was initially interested in maintaining the hegemonic position in Eastern Europe. Břetislav I gave the occasion to intervene in Bohemia when he tried to expand his dominion to the north. In 1039 he invaded Poland, conquered and destroyed Krakow and entered Gniezno with his troops . The relics of St. Adalbert was Břetislav after Prague convert to his claim to the legacy Bolesław Chrobry to substantiate. Since Poland was under German suzerainty , this meant an attack on the Roman-German ruler. In October 1039 Heinrich therefore prepared a campaign under the leadership of Ekkehard II of Meissen . Břetislav gave in, promised to bow to Heinrich's demands and held his son Spytihněv hostage. In the course of the following year, however, the Bohemian failed to meet his obligations, but prepared himself for defense and secured the support of the Hungarians. In August Heinrich therefore undertook a campaign against Bohemia, but suffered a heavy defeat. Most of the warriors of the contingent died, the Fuldaer Totenannalen name numerous individual fates. An offer to negotiate in the following year was nevertheless answered by Heinrich with a demand for unconditional submission. The fighting resumed in August 1041. This time Bohemia was attacked from the west and north. In September 1041 the armies united in front of Prague. There was no battle because Břetislav found himself on his own. His ally Peter of Hungary had in the meantime been overthrown. In order to prevent further devastation of his country, Břetislav was left with only submission. In October 1041 he appeared at the court in Regensburg, brought rich gifts and paid the owed tribute. At the request of his brother-in-law, Margrave Otto von Schweinfurt , he was enfeoffed again with the Duchy of Bohemia. He had to cede his Polish conquests and recognize the German suzerainty, but he was allowed to keep Silesia.

Older research saw the conflict with Bohemia as a starting point for a tighter organization of the border regions. Heinrich is said to have distinguished himself as a foresighted founder of brands with the help of which the borders were to be secured according to plan. The brands Cham , Nabburg , a Bohemian mark and a so-called Neumark, which is said to have been directed against Hungary in the southeast, were attributed to his “state-creating” initiative. Friedrich Prinz, however, questioned this assessment . The concept of rule led to extremely dangerous situations in the border areas of the empire, provoked unnecessary hostilities and exacerbated existing ones. In contrast, Daniel Ziemann recently recognized no “larger-scale political concepts” in Salier’s policy on Hungary.

In the course of the military actions against Bohemia, Hungary also moved into Heinrich's field of vision. After the early death of his son Heinrich , Stephan I had adopted his nephew Peter, the son of his sister and the Venetian doge Ottone Orseolo , and made him heir to the throne. However, a coup led Sámuel Aba , a brother-in-law of Stephen, to power; the backgrounds cannot be illuminated. Peter, who still stood on Břetislav's side in 1039/40 and was one of Heinrich's opponents, found himself a refugee in 1041 at the Regensburg Court Congress. Sámuel Aba invaded Carinthia and the Bavarian Ostmark in the spring of 1041 . This provoked Heinrich's backlash, which led to the regaining of the areas between Fischa, Leitha and March , which were ceded to Stephan in the peace of 1031 . On July 5, 1044, the king defeated the numerically superior Hungarians in the battle of Menfö an der Raab . After the battle, Heinrich threw himself barefoot and wrapped in a penitent's robe to the ground in front of a relic of the cross and asked his entire army to do the same. A little later he walked barefoot through Regensburg and thanked God for his help in the fight. The city's churches received donations. Peter was enthroned again in Stuhlweissenburg and recognized the feudal sovereignty of the empire. Sámuel Aba was executed as a traitor after his capture.

However, this did not mean that the situation in Hungary could be stabilized in the long term. When Heinrich set out on his journey to Rome, Peter had already been overthrown by Andreas , a nephew of Stephen I, who had returned from exile . Andreas tried to normalize relations with the empire in order to consolidate his rule. According to Hermann von der Reichenau's report , he offered the emperor submission, annual tribute and devoted service "if he allowed him to keep his empire". Heinrich's primary goal, however, was to defeat Andreas in order to avenge his protégé Peter. Two campaigns he undertook in 1051 and 1052 were unsuccessful. In 1052 Pope Leo IX mediated . a peace. This turned out to be detrimental to the empire, as an impairment of the honor regni , as the Annales Altahenses critically noted. At the end of his reign Heinrich was far from keeping Hungary, Bohemia and Poland dependent on feudal rights. He could not even be sure of his Bohemian vassals, as Duke Spytihněv II , who was raised in 1055, established closer ties with Hungary.

Promotion of Speyers

Empress Gisela died in March 1043. She was solemnly buried in Speyer. At the funeral, the king appeared barefoot and in a penitent's robe, threw himself on the ground with outstretched arms in the shape of a cross in front of the crowd, and through his weeping moved all those present to tears. Research speaks of “Christomimetic royalty” for this period. The kings emulated Christ's humble self-denial, thereby demonstrating their qualifications for the royal office.

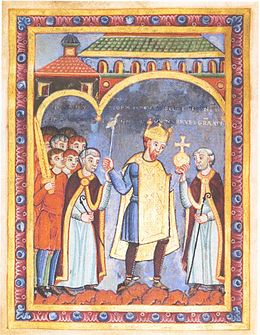

Heinrich promoted Speyer much more than his father Konrad. At the end of 1045 at the earliest, or shortly before he left for Italy for the coronation of the emperor, he gave the church the Codex Aureus Escorialensis, a magnificent gospel, also known as the Speyer gospel . The images of rulers are among the most splendid of the Middle Ages. They show the Salian dynasty as it emerged in 1045. The left picture shows the first generation with Emperor Konrad II and his wife Gisela. The code of splendor begins with the emperor's tears, with his repentance and penitence. Konrad implores the grace of God. The right picture represents the second generation with Heinrich III. and his wife Agnes. St. Mary is enthroned as Queen of Heaven in front of the Speyer Cathedral, which is consecrated to her. Henry III, the ruling ruler, bows down before her and hands her the golden book of the Gospels.

The foundation intention of the images of the rulers is controversial. Johannes Fried suspects that Agnes' pregnancy and thus the desire for an heir to the throne were the specific cause. Agnes had given birth to a daughter as the first child at the end of September / beginning of October 1045. At the same time, Heinrich fell so seriously ill that one had to reckon with his death. The continuation of the entire Salian royal family seemed endangered. With these pictures, Maria, the patron saint of the Speyer Cathedral, should be voted graciously. Agnes was entrusted with her intercession so that she might give birth to an offspring. In contrast, Mechthild Black-Veldtrup refers to the upcoming trip to Rome and the dangerous accompanying circumstances, not least with regard to the travel strains of the pregnant queen. Ludger Körntgen emphasizes the aspects of the memoria : liturgical remembrance of the living and the deceased. The Codex Aureus also contains the sentence: Speyer will shine in splendor through King Heinrich's favor and gift (Spira fit insignis Heinrici munere regis) .

After the mother's death, the cathedral was considerably expanded and enlarged by a third. With a total length of 134 meters, it rose to become the largest church in Western Christianity. The Salian burial place was also expanded. The king laid out a burial ground which, with a size of 9 × 21 m, was unrivaled in any other place of worship in the empire. Space was created for future burials of rulers, which paved the way for a continuous royal burial. Heinrich can be identified almost every year in “his beloved place” until Easter in 1052. At Easter in 1052, however, there were rifts between Heinrich and the Speyer Bishop Sigebod , which apparently related to the burial place in the cathedral. The contemporary report by Hermann von der Reichenau states that Heinrich Speyer “disliked Speyer more and more”. Compared to other historians, the importance of the cathedral for Heinrich III. accepts Caspar Ehlers . Since Heinrich's coronation as emperor in 1046, Speyer had increasingly faded into the background. Out of a total of eleven documents for Speyer, only two have survived. Goslar came to the fore as the new focal point. Heinrich's intestate burial in Goslar and the corpse burial in Speyer illustrate, according to Ehlers, the reservations Heinrich had about Speyer.

The last picture, which Heinrich himself commissioned around the middle of the 11th century, has come down to us in the so-called Codex Caesareus. As in the Codex Aureus, Heinrich and his wife stand alone with Christ, bowed and humble again. In none of the pictures commissioned by him are there any great people in the vicinity. It is the last image of a ruler of this kind from the Middle Ages.

Imperial coronation and reform papacy

The years 1044 to 1046 marked a time of serious crisis for the papacy. The causes can be found in the disputes of the Roman aristocratic factions over the rule of the city, in which the popes themselves were a party. In the autumn of 1044 Pope Benedict IX. expelled from the Tusculans as a result of the Roman nobility battles. At the beginning of the year 1045 the Crescentier elected their partisan Bishop Johannes von Sabina to be Pope Silvester III in his place. Benedict IX however, succeeded in March 1045 to oust New Year's Eve and to recapture the papal throne. For unknown reasons, however, Benedict ceded his dignity on May 1, 1045 to the archpriest Johannes Gratianus von St. Johann at the Porta Latina for a large payment of money. The new Pope took the name Gregory VI. on.

According to current research, Heinrich moved to Rome because of the imperial coronation and not to end the papal schism. Heinrich set the date around September 8th, the day of the birth of Mary, as the time for the departure to Italy in 1046. On this occasion he made a number of donations to the Church of Speyer. As the first Roman-German ruler, Heinrich was able to enter Italy without encountering resistance. On October 25, 1046, a synod took place in Pavia , which mainly opposed the sale of church offices. On November 1, Heinrich met Pope Gregory VI, who had been in office for more than a year. together. The talks apparently went smoothly at first, because in Piacenza they both signed up for a prayer fraternity. The king then seems to have received information that aroused the suspicion that Gregory VI. had bought the dignity of the Pope. This raised a fundamental problem: if the imperial crown was beyond any doubt, Heinrich needed a coronator whose dignity and legality were beyond question. The king had a synod called in Sutri on December 20, 1046 . It is the first reform synod of the reign of Henry III. to look at, which set itself the goal of going against the simony . The synod came to the conclusion that Benedict IX, who was not present, was no longer Pope. The published New Year's Eve received a penalty, the extent of which is unknown. Gregory VI. presided over as incumbent Pope, but drew so much criticism that, under pressure from the Assembly, he was ready to resign and paved the way for a new, unencumbered Pope. On December 24, 1046, another synod was held in Rome, which continued the reform work begun in Sutri, Benedict IX. formally resigned and elected a new Pope. Heinrich's preferred candidate, Archbishop Adalbert von Hamburg-Bremen , turned it down and suggested his friend, Bishop Suidger von Bamberg. As a result, Suidger was raised to Pope on December 25, 1046 as Clemens II .

Immediately afterwards, the new Pope Heinrich and his wife Agnes crowned Emperor and Empress. For Agnes, the designation Consors Regni has prevailed in the law firm , Heinrich also had the late antique title Patricius Romanorum assigned to him. The Patricius was traditionally regarded as the patron of Rome and was entitled to participate in the elevation of the Pope. So the new emperor was able to justify his actions retrospectively.

In January 1047, at the synod convened in Rome, the purchase of church offices was sharply condemned and resolutions were passed on how to proceed against simonist priests. In the same month Heinrich, accompanied by Clemens II, advanced to southern Italy to clarify the political situation in the Lombard principalities. He withdrew the principality of Capua from Waimar IV , who was striving for supremacy in this area, and transferred it again to Pandulf IV , who had once been deposed by Conrad II. The main reason for this measure may have been that Pandulf was in close contact with the Tusculans and could endanger Rome and the Papal States with his power. At the same time, the Norman leaders Rainulf with Aversa and Drogo von Hauteville were enfeoffed with his Apulian land. This provision was at the expense of the legal claims of the Byzantine Empire, from which the Normans had already wrested parts of Puglia. This was the first time that Norman leaders entered into a direct feudal bond with the empire and achieved legalization of their conquered land holdings. Apparently Heinrich tried to strike a balance between Norman and native leaders. However, this reorganization did not last; Waimar soon reappeared as a feudal lord of the Normans. Heinrich returned to Germany before the summer of 1047.

With the uprising of Pope Clement II, a development was initiated that led to an interlocking of the empire with the church. Clemens and his successors had been members of the imperial episcopate and retained their diocese even after they were made pope. This made it possible to include the Roman bishopric more closely in the network of relationships within the imperial church. Clemens was followed by Bishop Poppo von Brixen as Pope Damasus II in 1047/48 and Bishop Bruno von Toul as Pope Leo IX in 1048/49 . With the five-year pontificate of Leo IX. the struggle over the grievances in the church ( priesthood , simony ) reached its first climax. Leo collected personalities in his environment such as the Liège cathedral canon Friedrich, the later Pope Stephan X , who became Chancellor of the Roman Church, Hugo Candidus, clergyman at the Remiremont convent , Humbert, monk of the Moyenmoutier Abbey , who became Cardinal Bishop of Silva Candida , but also the young Roman cleric Hildebrand, who later became Pope Gregory VII. They were all shaped by the spirit of church renewal. With the pontificate of Leo IX. Efforts to centralize and organize the church as a whole received a boost. The papacy began to break away from its regional ties to the Roman-Central Italian region and developed into an institutionally anchored primacy. Leo traveled to southern Italy, Germany and France and visited the border regions of Hungary himself. During his five-year reign, twelve synods chaired by him personally met in Germany, France and Italy on the reform of the clergy. Efforts to renew the church were made by Emperor Heinrich III. supports. His rule was also based strongly on church norms and canonical scriptures. Heinrich fought the simony, and the priest sons were given - probably against the will of most of the imperial bishops - no chance to get a bishopric. At the Mainz Synod of October 1049, a close cooperation between the two highest powers became clear. But a few years later Leo did not succeed in getting Henry's support against the expanding Normans in southern Italy. On June 18, 1053, the papal army suffered a crushing defeat near Civitate in northern Apulia ( Battle of Civitate ). Leo was captured by the Normans and died soon after his release. In the following year Heinrich arranged for a trusted advisor, Bishop Gebhard von Eichstätt, to be appointed Pope Viktor II.

Imperial politics

Nobility politics

When Duke Conrad the Younger of Carinthia died on July 20, 1039, Heinrich initially did not reoccupy this duchy either. The three southern German duchies of Bavaria, Swabia and Carinthia were thus under the control of the king. Never before had a Roman-German ruler had such a broad power base when he took office. Bavaria was awarded to the Luxembourgish Heinrich VII in 1042 without a choice of the local greats in Basel . In 1045 the King of Swabia transferred Otto II to the Ezzone . Heinrich was able to expand his position on the Lower Rhine because Otto left the Suitbertinsel ( Kaiserswerth ) and Duisburg to him. The leading role of the Ezzone in imperial politics is illustrated by the considerations of a group of princes, whom Heinrich Ezzonen succeeded Henry III. to determine when he fell so seriously ill in autumn 1045 that one expected his death. But Heinrich got well again. 1047 received the Swabian Count Welf III. the Duchy of Carinthia. All the newly appointed dukes were strangers. So they were dependent on the support of the royal central authority. The official character was thus preserved, the inheritance of the ducal dignity and the formation of new ducal dynasties could be prevented.

The new dukes in Bavaria and Swabia died as early as 1047. At the beginning of 1048 Heinrich transferred the Duchy of Swabia to Otto (III.) Von Schweinfurt from the Franconian line of the Babenbergs . Bavaria was awarded in February 1049 against the usual co-determination of the Bavarian nobility and to a stranger to the country, the Ezzonen Konrad . Soon there must have been disagreements between the emperor and the new Bavarian duke. According to the founding report of the Brauweiler Abbey , the reason for the later removal of Konrad was the fact that he had spurned marriage to one of the imperial daughters and married Judith von Schweinfurt against the will of Heinrich Judith . However, the background to the conflict that triggered it is more likely to be found in different views of Heinrich's policy on Hungary. The aristocratic faction around Duke Konrad has probably sought a compromise with the Hungarians. The emperor's uncle, Bishop Gebhard III. von Regensburg , played a decisive role in the deposition of Konrad. Gebhard was considered an exponent of a position hostile to Hungary. An open hostility is said to have existed between Gebhard and Konrad from 1052 at the latest. Heinrich took vigorous action against the opposition that was forming. At Easter 1053 both parties were summoned to court. On April 11th, the verdict against Konrad followed at the Merseburg Hoftag. He was found guilty and deposed as Duke of Bavaria. Heinrich commissioned Bishop Gebhard I to manage the duchy.

In 1053 the deposed Duke Konrad managed to flee to the Hungarian enemy and to rally and mobilize large circles of Bavaria against the ruler. In 1055 a group of powerful princes joined together in the southern German duchies against the authoritarian rule of the king, including the Bishop of Regensburg, the powerful Duke Welf III. and the deposed Duke Conrad I of Bavaria. The reasons remain in the dark; the conspirators planned to murder Heinrich. Conrad I was planned as his successor. The planned regicide reveals the greatest tensions in the regulatory system. Never before had such events occurred in the Frankish-German domain. The coup was, however, due to the sudden death of Welf III. and Konrads I. foiled. The Niederaltaich annals attributed this to divine intervention. According to the founding report of the Ezzonen Monastery , which has belonged to the Archbishops of Cologne since 1051 , Heinrich is said to have commissioned his cook to murder Konrad by poison. But there are no parallel sources that even hint at such allegations. Bishop Gebhard von Regensburg was summoned, convicted and imprisoned, but soon afterwards released again and accepted by the emperor at the mercy of the following year.

Salian-Billungian relations deteriorate

According to the prevailing research opinion deteriorated between Heinrich III. and Saxony 's relations. Saxony was viewed by Egon Boshof , Wolfgang Giese and Stefan Weinfurter as the place of the earliest opposition to the Salier. In contrast, Florian Hartmann recently analyzed the Duchy of Saxony and found an almost conflict-free time in this region. The idea of rebellious Saxons under Heinrich III. is based primarily on the use of sources that were written at a later time and report under the impression of the Saxon War.

During the reigns of Conrad II and Henry III. the relationship between the Salians and the Billungers was initially characterized by indifference. Saxony was given the character of a secondary country . According to Gerd Althoff, a process in 1047 marked a turning point in Salian-Billungian relations. In that year Heinrich visited the Archbishop Adalbert von Bremen and stayed at the royal court in Lesum. Adam von Bremen cites the reason for this visit that they “wanted to discover the allegiance of the dukes”. The Kaiser was saved from an attack just in time. The Billunger Count Thietmar , the brother of Duke Bernhard II of Saxony , is said to have prepared an assassination attempt. This plot was revealed to Heinrich through a vassal of the count. The allegation should be clarified in Pöhlde with a judicial duel. It was unusual for a nobleman, the Billunger Thietmar, to stand up against his own vassal; Heinrich at least allowed this to happen, or perhaps even requested it himself. In a duel, the Billunger died of his wounds, whereupon his son brought the vassal into his power and killed. The emperor, in turn, avenged this by exiling Thietmar's son for life and confiscating his property. The severity and consistency with which Heinrich III. took action against the Billunger and his son, the relations with the Billungern deteriorated. According to Florian Hartmann, however, these events did not result in any outrage on the part of the Billungers against Heinrich. Rather, half a year later, Duke Bernhard supported the awarding of a wild bans to the Bremen church.

Under Heinrich, a new way of dealing with conflicts between king and great began, which differed considerably from the practice in the Ottonian period. In an amicable settlement, the opponents of the king had so far declared themselves ready to give satisfaction through submission at the end of disputes, whereupon the king showed leniency and forgiveness. Heinrich III accepted this well-rehearsed ritual. no longer. The consequences for those affected were now much harder. For the first time under Heinrich , the death penalty was set for crimes against majesty (contemptor imperatoris) , i.e. for every rebellion against the ruler. The behavior and reactions of the Billungers make it clear that they did not approve of the practice used against their relatives. The vigorous expansion of the imperial estate in Saxony, where the Salians did not own any property, also caused displeasure. All attempts by the kings to tighten the administration and to promote the expansion of the imperial property sparked resistance there. The Saxon property was used more intensively for the upkeep of the royal court. According to a southern German chronicler, Saxony developed into the "coquina imperatoris" ("Emperor's kitchen").

The royal palace had already been relocated from Werla to Goslar under Heinrich II . Henry III. promoted Goslar with several privileges, since silver mining provided the royalty with considerable income. The new Palatinate with the Palatinate Monastery of St. Simon and Judas became a central place of the imperial administration. However, tensions with the Saxons deepened when Adalbert was appointed Archbishop of Hamburg-Bremen. Adalbert developed into a bitter opponent of the Billunger. The Billungers had persecuted himself, his church and the church people with deadly enmity. Duke Bernhard viewed the archbishop from the outset as his opponent, who was sent to his territory for surveillance and as a spy, "in order to betray the country's weaknesses to strangers and the emperor".

Clashes in Lorraine

In Lorraine, Duke Gozelo had ruled both Lower Lorraine and Upper Lorraine from 1033. His death on April 19, 1044 led to serious disputes between Heinrich and Gozelo's younger son Gottfried the Bearded about the succession plan . The specific facts can hardly be elucidated from the sparse sources. According to the presentation of the Annales Altahenses and Hermann von der Reichenau , it seems that Gottfried opposed the will of the father as well as the order of the king. Gozelo had already transferred the Duchy of Upper Lorraine to Gottfried during his lifetime . Lower Lorraine, however, was given to his younger son Gozelo II - despite his cowardice (ignavus) and ineptitude ( quamvis ignavo ). However, the annalist of Niederaltaich clearly ascribes the decision to the king alone to give the duchy of Lower Lorraine to his older son after Gozelo's death. Henry III. Gottfried only wanted to award Upper Lorraine. Apparently, through the death of Gozelos I, he used the opportunity to smash the Lorraine power complex. At the death of his father in 1044, Gottfried the Bearded objected and also wanted the duchy of Lower Lorraine. Gottfried referred to his previous important position and probably also to the will of his father. As a further argument, the idoneity principle may have played a role in the following disputes, since Hermann von Reichenau testifies to the inability of Gozelos II, whom the King of Lower Lorraine gave to administer.

Heinrich remained adamant in the conflicts and demanded the recognition of Gozelos II as duke, although Gottfried declared his willingness to provide whatever consideration he asked if he could only keep both duchies. For Heinrich the official character of the ducal dignity was decisive and while maintaining his official sovereignty he had the intermediate powers at his discretion. In the following conflicts, Gottfried is said to have allied himself with Henry I of France . This high treason, as handed down in the Annales Altahenses, was questioned by Egon Boshof in a fundamental study.

Gottfried was stripped of his imperial fiefs through a prince's verdict, which meant the loss of both Lorraine. In the winter of 1044 Heinrich began the campaign. At the same time, riots broke out in Burgundy, which, however, could be ended without any major intervention from the king. In January 1045 Heinrich was able to accept the submission of the Burgundian rebels. During the conflicts, Gottfried was politically isolated. Heinrich managed to win over the leading families in Lorraine, especially the Ezzone, but also the Lützelburger, for his cause. The Lorraine episcopate also proved to be reliable support for the king. On a farm day in Goslar in the spring of 1045, Heinrich received the homage to a son of Baldwin V of Flanders and assigned him a border area adjacent to Flanders, to which Gottfried had made a claim. In doing so, he won Baldwin's neutrality, but at the same time supported the Flemish expansion into the empire. The military clashes dragged on for a long time, as a severe famine forced the warring parties to curtail their actions. It was not until July 1045 that Gottfried submitted and was taken into custody by Heinrich im Giebichenstein . A decision at a court day in Aachen in May 1046 was awarded to him by the Duchy of Upper Lorraine after his release from custody. As a guarantee of future good behavior, he had to hold his son hostage. Lower Lorraine was transferred to the Lützelburger Friedrich , whereby the Lützelburger emerged as beneficiaries from the disputes. They now ruled over two duchies and were able to maintain a key position in Upper Lorraine with the diocese of Metz . By the middle of the year the situation was considered to have calmed down and settled so that Heinrich was able to make preparations for the Italian train.

Obviously, beyond his submission, Gottfried tried hard to find a reconciliation with Heinrich. The snub had to hit him all the harder when the emperor at the grave of the apostle princes - probably on the occasion of his imperial coronation - announced an indulgence and publicly pardoned his opponents and enemies, but Gottfried expressly excluded. The exclusion from the act of forgiveness profoundly contradicted the imperial peace policy and illustrates how deep Heinrich's distrust of Gottfried must have been. Probably after Heinrich's return from Italy in May 1047, Gottfried began to prepare for a renewed outrage. More by chance than deliberately planned, Gottfried, Dietrich von Holland , Baldwin V von Flanders and Count Hermann von Hainaut came together to form a coalition. In the following military conflicts, the imperial palaces of Nijmegen and Verdun were destroyed. Heinrich was able to encircle the uprising through a meeting with Henry I of France and through agreements with the Danes and Anglo-Saxons, who agreed to help the navy. In the following year he succeeded in turning things around. In January 1049 Dietrich of Holland fell. After Gottfried in 1049 by Pope Leo IX. had been excommunicated , he submitted to the ruler in Aachen in July of this year and had to renounce his duchy. The fact that Gottfried still found advocates among the princes suggests that they certainly considered the right of Lorraine. Gottfried was imprisoned in Trier under the care of Archbishop Eberhard . In autumn Baldwin was also defeated by Flanders. Heinrich had thus faced the greatest danger to his rule to date and achieved his goal of smashing an oversized duchy and subjecting it to better control of the central authority. In the long run, however, the situation for the empire turned out to be disadvantageous. The weakening of the Lorraine ducal power led to the fact that the ruling nobility could not be controlled less and less. The successors of Gottfried in the divided duchy did not have the basis to represent the interests of the empire powerfully. The political fragmentation of the western border area led to a loss of power in the empire. The main beneficiary was Count Baldwin V of Flanders.

After his release from prison, Gottfried was soon looking for ways to build up a new position of power. Without consulting the emperor, he married Beatrix von Tuszien , the widow of Margrave Bonifatius von Tuszien, who was murdered in 1052 . The enormous position of power that he thus achieved in northern Italy prompted Heinrich to move to Italy for the second time in the spring of 1055. Gottfried quickly left for his home in Lorraine, Beatrix and her daughter Mathilde were captured and led into the kingdom at the end of 1055. Together with Pope Viktor II, who has been in office since April 13, 1055, a reform synod was held in Florence at Pentecost . Viktor transferred the Duchy of Spoleto and the Margraviate of Fermo from Heinrich . Negotiations on the problem of Norman expansion have started with the Lombard principalities and Byzantium, but nothing is known about the result. Heinrich returned to Germany in November 1055. The most important goal, the consolidation of rule in Italy, had been achieved. The Norman question, however, remained unanswered.

Church politics

Henry III. strengthened the episcopal churches at the expense of the imperial monasteries. He confirmed the transfer of former imperial abbeys and monasteries to the bishops of Bamberg , Brixen , Minden , Cologne and Passau . However, this does not mean that measures to strengthen the remaining imperial monasteries were discontinued. The protection and promotion of these monasteries were inextricably linked with the well-being and existence of the king and empire (stabilitas regni vel imperii) . Equipping the monasteries and monasteries with possessions and rights not only served to secure the salvation of the king's soul, but also guaranteed the continued existence of the empire.

Above all, however, the empire's episcopal churches were promoted. Between 1049 and 1052 Hildesheim received six major donations. Three donations were made to Halberstadt during the same period. Following the government practice of his predecessors, Heinrich further expanded the imperial church by granting and confirming immunities , forests, monetary sovereign rights and counties. As a result, the imperial church was able to effectively render the services resulting from the gifts of property and rights for the ruler and to fulfill the royal service (servitium regis) . The arenas of the diplomas occasionally emphasize that the ruler has to look after all the churches in the empire and to encourage each one in their task of serving God. In all difficult situations during his reign, the imperial church proved to be a solid support. Heinrich exercised significant influence on the elevation of the bishops and the heads of the imperial abbeys and imperial monasteries. The royal decisions were entirely in line with the church reform trend. With the succession plan in Eichstätt in 1042, Heinrich did not accept the candidate Konrad proposed by Bishop Gebhard von Regensburg because he was the son of a priest. Heinrich also paid attention to the high quality of the officials. They had to know the church laws and apply them in their churches. He introduced an important innovation in the ceremonial of the bishopric. He was the first ruler to use the ring in addition to the staff during the investiture. The ring is a spiritual sign that symbolizes the marriage of the bishop to his church. Under his son, this act led, under the slogan investitura per annulum et baculum (investiture with ring and staff) to massive conflicts with the representatives of the Gregorian reform .

Until 1042, the year Poppos , the patriarch of Aquileia died , he led a largely independent territorial and ecclesiastical policy. It was shaped by sharp conflicts, including foreign policy, into which he had drawn Konrad II. As early as 1027 he had his rival Grado destroyed in order to enforce his claim as patriarch , and this happened again in 1044. This threatened an open conflict with Venice , on whose territory Grado was located. In fact, the city recaptured Grado after Poppo's death. Karl Schmid is one of the few who commented on this scarcely researched process: “It is symptomatic, with a view to Aquileia and its priority as patriarchy, that Heinrich III. Poppos did not continue his anti-Gradensian and thus anti-Venetian politics after his death [...] ”.

The interlocking of the court chapel with the imperial church was further strengthened under Heinrich, the efficiency of the court chapel in royal service reached its peak. In 1040 the top offices were reorganized. Since 965 the Archbishop of Mainz had held the highest ecclesiastical office of the court orchestra with the dignity of arch chaplain . As arch chaplain, he was also arch chancellor of the East Franconian-German Empire. At the time of Heinrich, the Archbishop of Mainz Bardo was increasingly named Arch Chancellor in the documents . The office of arch chaplain was separated from that of arch chancellor. Eventually the title archicapellanus was completely replaced by capellarius . At the same time, the function of the chief chaplain in the court chapel was exercised by a leading chaplain. He was subject to the ruler's instructions to a much greater extent and was constantly present at court. This increased the effectiveness of the administration. With the expiration of the office of the Archkapellans, the Arch Chancellor moved to the head of the ecclesiastical court offices. The Arch Chancellor for Germany, the Archbishop of Mainz, had the privilege of sitting next to the Emperor (primatus sedendi) , and thus documented his priority over the other greats. The Archbishop of Cologne, Hermann II, held the office of Arch Chancellor for the Italian part of the empire . For Burgundy, Henry III. another Arch Chancellery and transferred it to Archbishop Hugo von Besançon .

By founding palatinate monasteries in his favorite Palatinate Goslar and in Kaiserswerth, Heinrich III. an even closer connection between the royal rulership center and the church, which broadened the personnel base of the royal court chapel. The Pfalz Goslar with the Pfalzstift St. Simon and Judas became the most important training center. Nine documents for the Pfalzstift have been received. They are all donations with which the Pfalzstift was richly endowed. With the apostles Simon and Jude , Heinrich chose the day saints of his birthday (October 28) as patron saints. The importance Heinrich attached to his birthday is unusual for a medieval ruler, since at this time it was not the date of birth but the day of death - as the beginning of life in God - that was important.

Under Henry III. a particularly large number of chaplains were appointed bishops. The "Kapellan bishops" should guarantee particularly close ties between the episcopal churches and the ruling court. The chaplains who were active in the administration and administration of justice performed masterpieces in this area. The performance of the court chancellery meant that the medieval royal charter reached its peak at this time.

Peace program

Preservation of justice and peace were among the king's most important duties. The idea of "peace through rule" originated in the ancient world and was discussed intensively in the early Middle Ages, but faded into the background in the Ottonian period. With Heinrich this idea came to the fore again. The central idea of his kingship was the idea of peace. In Wipo's Tetralogus , the ruler is asked to actively tackle the imperial task of order. He should lead the entire world (totus orbis) to God-pleasing and God-willed comprehensive peace (pax) . The king is celebrated as the "author of peace" (auctor pacis) and "hope of the world" (spes orbis) . Penance and mercy were among the foundations of Heinrich's peace orders. The commandment of general peace to all was always connected with his weeping penance. As early as his stay in Burgundy in 1042, the chroniclers report that he had secured the peace without, however, giving any further information about the nature of his approach. At the Synod of Constance in October 1043, a few weeks after the victorious Hungarian campaign, Heinrich exhorted the people to make peace. At the end of the synod he had issued a royal edict with which he ordered “a peace that has not been known for many centuries”. It is uncertain what the immediate driving force behind the peace idea was. Possibly there were suggestions from the southern French-Burgundian region, where the God's peace movement had spread widely. In the union of bishops and princes, certain groups of people as well as certain ecclesiastical festivals and periods of time were placed under special protection ( pax Dei and Treuga Dei ). The pronounced piety of the second Salic ruler and the Burgundian origin of his wife, who is also described as extremely pious, speak for influences from this side. However, in contrast to the God's Peace Movement, this peace should by no means be concluded together with the greats of the kingdom, but solely by ruling ordinance.

Particularly violent attacks on this peace concept came from church circles. In a letter from 1043, Abbot Siegfried von Gorze takes the view that Heinrich was committing a sin by marrying Agnes. The main aim of the letter was to prove that Heinrich and Agnes were too closely related and that the planned marriage was therefore canonically inadmissible. The court's argument that this would allow the German and Burgundian empires to be merged into one great peace unit was described by Siegfried as erroneous and pernicious. The abbot spoke of a pernicious peace (pax perniciosa) because it would come about in disobedience to canonical and thus divine laws.

Succession to the throne and early death

From his first marriage to Gunhild, Heinrich had a daughter named Beatrix . His second marriage had three daughters Adelheid (1045), Gisela (1047) and Mathilde (1048). The couple took care of the maintenance of the Salic memoria in the Saxon ladies' pens in an exemplary manner. At the age of seven, Beatrix became head of the Quedlinburg and Gandersheim monasteries in 1044/45 . Adelheid was also given an education at the Quedlinburg convent early on and later headed Gandersheim and Quedlinburg as abbess for more than 30 years .

In 1047 Archbishop Hermann of Cologne asked to pray for the birth of an emperor's son. On November 11, 1050, after seven years of marriage, the long-awaited presumptive heir to the throne was born. His birth was finally greeted with a long sigh . The parents chose the name of their grandfather Konrad for their son. On Christmas 1050, the imperial father made the present members swear allegiance to the still unbaptized son. Archbishop Hermann performed the baptism in Cologne on Easter (March 31, 1051). The reform abbot Hugo von Cluny took over the sponsorship and pleaded for the renaming of the child to Heinrich . The choice of Hugo as godfather of the heir to the throne documents the close ties between the Salian ruling house and the religious currents of that time. When the emperor had his three-year-old son elected his successor in the royal office in the royal palace of Trebur (south of Mainz on the right side of the Rhine) in 1053 , the voters expressed a reservation that had never been seen in the history of the royal election. They only wanted to follow the new king if he became a just ruler (si rector iustus futurus esset) . A year later the child was crowned and consecrated king on July 17, 1054 in Aachen by Archbishop Hermann von Köln. A little later, the care of the second son Konrad, born in 1052, was settled: the Duchy of Bavaria was transferred to him. The second-born was probably intended as a “personnel reserve” for the successor to the first-born, which can no longer be contested. In the summer of 1054, Agnes gave birth to Judith, another daughter. After the second son Konrad had already died on April 10, 1055, Heinrich privato iure transferred the Bavarian duchy to his wife for an indefinite period of time, without taking into account the electoral rights of the grandees.

Henry III. also initiated the later marriage of his successor in a binding manner. On Christmas 1055, the heir to the throne in Zurich was betrothed to Bertha from the house of the Marquis of Turin . The purpose of the marriage was to strengthen the Turin margrave house against the Lorraine-Tuscan ducal and margrave house, which was hostile to Heinrich, and to bind it to the Salian imperial house.

Heinrich died unexpectedly on October 5th, 1056 at the age of 39 after a brief, serious illness in the Königspfalz Bodfeld am Harz, where he had been hunting. On the death bed, he made sure that the greats confirmed his succession to the throne by re-electing the son for the last time. According to the Niederaltaich annals , the empire enjoyed peace and quiet "when God, out of anger over our sins, covered the emperor, whom he had gifted, with a serious illness". The internal organs were buried in the Palatinate Church of St. Simon and Judas in Goslar. The body was transferred to Speyer and buried on October 28, 1056 at the father's side. Heinrich gave both churches special care, and in Speyer in particular his memory was fostered in the following period. His most important donations for the Speyer Church are noted in a necrologium ( Necrologium Benedictoburanum ). When Godfrey of Viterbo Heinrich is the first time with the nickname niger recorded (the Black). The nickname gradually disappeared in the 19th century. The affairs of state for Heinrich's son of the same name were initially carried on by his mother Agnes von Poitou. However, their rule came more and more into the criticism of reform-minded clergy like the Archbishop Anno of Cologne .

effect

Judgments of contemporaries

The judgments made by contemporaries paint a mixed picture. Unlike his father, Heinrich III. no historiographer found who would have dominated the judgment of posterity. Konrad's court historiographer Wipo described the duties of the ruler in his tetralogue , a kind of imperial mirror, presented at Christmas 1041 , and in his proverbia , and developed the basic principles of a royal ethic. Education, science and wisdom appear here as prerequisites for just governance. Bern von Reichenau describes Heinrich in his letters of dedication as an invincible bringer of peace, as the most benevolent and fairest ruler of the world and as a promoter of the faith and glory of kings. He hoped that Henry's rule would mark the beginning of a new age of unity and peace. Praise and award seals praise Heinrich as a peace-loving ruler and compare him to the Old Testament King David . This comparison can already be found in the Merovingian and Carolingian times and Heinrich II. And Konrad II. Had already been praised as David, but the reference to David occurs under Heinrich III. especially often. David was associated with the idea of the beginning of a golden age. The court scholar and teacher of Heinrich, Wipo, compared his pupil several times with King David. There are two David songs in the Cambridge song collection . Even Petrus Damiani , the reformer and scholar at the papal court, celebrated Henry as the renewer of the Golden Age of David.

Clearly in contrast to the works created in the vicinity of the court are some mostly later voices from the circle of church reformers who, against the background of the advancing church reform, express criticism of Heinrich's measures in Rome. In the pamphlet “De ordinando pontifice” (On the elevation of the pope) Heinrich is vehemently denied the authority to remove or replace a pope, because priest, bishop and pope are placed above all lay people . A similar criticism has come down to us in the deeds of the Liège bishops (Gesta episcoporum Leodicensium) . It is reported that Bishop Wazo of Liège had the deposition of Gregory VI. Condemned because the Pope cannot be judged by anyone on earth. This is the first evidence of the debate about the status and legitimation of the king that began in the middle of the 11th century. The ruler's sacredness began to be demarcated from that of the clergy, and ultimately devalued.

Heinrich's style of rule did not only attract criticism from church reformers. According to the report of the monk Otloh von St. Emmeram in his Liber Visionum (Book of Visions), written around 1063, God himself punished the emperor with death because he ignored the so important virtue of rulership of helping the poor and taking care of their concerns have. Instead, he gave himself to money business, that is, an occupation that was the opposite of ideal rulership behavior. In the second half of the 11th century, denying the petitioners' concerns as king turned out to be a serious point of criticism when it came to the suitability of royal rule.

But criticism also came from a completely different side: the greats of the empire were dissatisfied with the style of rule. Heinrich's contemporaries noticed the ruler's increasing harshness in dealing with opponents. The chronicler Hermann von Reichenau wrote about the year 1053: “At this time both the greats of the empire and the less powerful grumbled more and more frequently against the emperor and complained that he had long since fallen from the initial attitude of justice, love of peace, piety, fear of God and various virtues, in which he should have made progress every day, more and more towards selfishness and neglect of his duties and will soon be much worse. ”However, there are no reports of the specific actions of the ruler that provoked this criticism.

The conservative Lampert von Hersfeld was concerned in his annals with the preservation of the old, Christian-monastic and political values, which he in the reign of Henry III. still looked embodied. But after the ruler's death, Lampert also noted a deep upset in Saxony because of Heinrich's behavior. In 1057 he reported about the plans of Saxon princes to murder the young Heinrich IV. The reasons given are the injustices that were inflicted on the Saxons by his father. One must fear that the son will follow in his father's footsteps in character and way of life.

Research history

Henry III. was also judged very differently in historical studies. This is due on the one hand to the inconsistent picture of the sources and on the other hand to the controversies about the meaning and consequences of the so-called investiture dispute that shaped the time of his son and successor. The time of Henry III. was and is considered by many historians as a high point in the imperial history of the Middle Ages. For research in the 19th century, German imperial glory reached its zenith under Conrad II and especially under his son. Albert Hauck wrote in his Church History of Germany that, after Charlemagne, Germany had no more powerful ruler than Heinrich. Ernst Steindorff came to a very balanced judgment in his “Yearbooks of the German Empire”. For the individual events he always tried to consider several perspectives. His conclusion emphasized the position of Henry III. between his father, who raised “nation and empire to a level of power and prosperity”, and the “collapse of the empire, the dynasty and the nation”, which Steindorff identified in the time of Heinrich's successors.

Heinrich's early death at the age of 39 has long been viewed in historical research as a "catastrophe of the greatest magnitude" for the empire. Paul Kehr said that Heinrich had bravely fought all dangers. He had rendered the Lorraine-Tuscan connection harmless and had the papacy under his control. For Kehr, therefore, was the anniversary of Henry III's death. "A black day for German history". The favorable assessment of Henry III. reached its peak in 1956 under Theodor Schieffer . To this day, all representations refer to Schieffer's work, even if they come to different conclusions. Schieffer described Heinrich's death as a "catastrophe of the greatest magnitude". For Schieffer, Heinrich was the "key figure in the history of the empire and the church".

In the second half of the 20th century, research took a turn in the assessment of the second Salic ruler. In 1979 Egon Boshof painted the picture of an empire in crisis for the second half of Heinrich's reign. Against the increasingly "autocratic style of government" Henry III. opposed the princes, who would have opposed this model to the conventional claim to participation in rulership. The discussion that gradually set in "about the right relationship between royal and spiritual power" had to "ultimately expand into an attack on the foundations of theocratic kingship". Following the results of Boshof, Friedrich Prinz drew “a rather sobering conclusion” for Heinrich's reign. In his portrayal, Prince put Heinrich's personality and his decisions more in the spotlight. In his personnel policy, the king had not had a lucky hand, especially when it came to the occupation of the duchies. For the past few years, Prinz has found “conditions similar to civil war”.

Stefan Weinfurter embedded his structural-historical representation in a concept of conflicting "order configurations". Rituals within the framework of the “configurations of order” represented by the king, such as the so-called “weeping of penance”, the ritual, publicly performed weeping of the ruler, and his peace order based on the imitation of Christ have therefore lost their integrative power and run counter to other contemporary ideas fundamentally. Other “configurations of order” were represented and, in the long term, also enforced, such as the “consensual principle” that grew out of the establishment of noble rule, that is, the participation of the princes in imperial affairs. The same applies to the "functional orderly thinking" that is valid in church circles, the division of society into functional groups, which no longer assigned the king a place in the ordo ecclesiasticus (order of the church) and thus contributed to a desacralization. In one of the most recent overview presentations, Egon Boshof counts Heinrich's reign "without a doubt one of the most glamorous epochs in medieval history", because "during his reign the order of harmonious interaction between secular and spiritual power was completed".

More recently, Heinrich III moved. again intensified in the interest of research. This is mainly explained by the publicly perceived discussion about his year of birth 1016 or 1017 and the associated anniversary. In 2015, the work of the Regesta of the Second Salic King began. In October 2016, the anniversary was celebrated with a specialist conference in Bochum. In 2017, on the occasion of the 1000th birthday of Heinrich III. held a series of lectures. From September 3, 2017 to February 28, 2018, the Kaiserpfalz Goslar presented the exhibition “1000 Years of Heinrich III. The 'Kaiserbibel' as a guest in Goslar ”. The exhibits include the "Codex Caesareus Goslariensis" Gospel Book from around 1050 on loan.

sources

- Adam of Bremen : Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum. In: Werner Trillmich , Rudolf Buchner (Ed.): Sources of the 9th and 11th centuries on the history of the Hamburg church and the empire. (FSGA 11), 7th edition, compared to the 6th with a supplement by Volker Scior, Darmstadt 2000, pp. 137–499, ISBN 3-534-00602-X .

- Annales Altahenses maiores. Edited by W. v. Giesebrecht, ELB Oefele, Monumenta Germaniae historica, Scriptores rerum Germanicarum in usum scholarum [4], 2nd edition. 1891. Digitized

- Hermann von Reichenau : Chronicon . In: Rudolf Buchner, Werner Trillmich (Hrsg.): Sources of the 9th and 10th centuries on the history of the Hamburg church and the empire. (Freiherr vom Stein Memorial Edition 11), Darmstadt 1961, pp. 615–707.

- Lampert von Hersfeld : Annals . Latin and German. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2000 (Selected Sources on German History of the Middle Ages Freiherr vom Stein Memorial Edition; 13).

- The documents of Heinrich III. (Heinrici III. Diplomata). Edited by Harry Bresslau and Paul Kehr. 1931; 2nd unchanged edition Berlin 1957. Digitized version (DD H. III)

literature

Overview works

- Egon Boshof : The Salians. 5th updated edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 3-17-020183-2 , pp. 91-164.

- Hagen Keller : Between regional boundaries and a universal horizon. Germany in the empire of the Salians and Staufers 1024 to 1250 (= Propylaea history of Germany. Vol. 2). Propylaen-Verlag, Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-549-05812-8 .

- Stefan Weinfurter : The Century of the Salians 1024–1125: Emperor or Pope? Thorbecke, Ostfildern 2004, ISBN 3-7995-0140-1 .

Representations

- Matthias Becher : Heinrich III. (1039-1056). In: Bernd Schneidmüller , Stefan Weinfurter (Hrsg.): The German rulers of the Middle Ages. Historical portraits from Heinrich I to Maximilian I. Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-50958-4 , pp. 136–153.

- Jan Habermann (Ed.): Emperor Heinrich III. Government, Empire and Reception (= contributions to the history of the city of Goslar / Goslar Fundus. Vol. 59). Publishing house for regional history, Bielefeld 2018, ISBN 978-3-7395-1159-7 .

- Gerhard Lubich , Dirk Jäckel (Ed.): Heinrich III. Dynasty - Region - Europe (= research on the history of the emperors and popes in the Middle Ages. Vol. 43). Böhlau, Cologne et al. 2018, ISBN 978-3-412-51148-7 .

- Johannes Laudage: Heinrich III. (1017-1056). A picture of life. In: Das Salische Kaiser-Evangeliar, Commentary Vol. 1. Edited by Johannes Rathofer. Publishers Bibliotheca Rara, Madrid 1999, pp. 87-145.

- Rudolf Schieffer : Heinrich III. 1039-1056 . In: Helmut Beumann (Hrsg.): Kaisergestalten des Mittelalter. Beck, Munich 1984, ISBN 3-406-30279-3 , pp. 98-115.

- Ernst Steindorff : Yearbooks of the German Empire under Heinrich III. 2 volumes. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt, 1963, ND from 1874 and 1881 (so far only biography of Heinrich III.).

Lexicon article

- Heinrich Appelt : Heinrich III .. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 8, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1969, ISBN 3-428-00189-3 , pp. 313-315 ( digitized version ).

- Tilman Struve : Heinrich III . In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages (LexMA) . tape 4 . Artemis & Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1989, ISBN 3-7608-8904-2 , Sp. 2039-2041 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Heinrich III. in the catalog of the German National Library

- Publications on Heinrich III. in the opac of the Regesta Imperii

Remarks

- ↑ Gerhard Lubich, Dirk Jäckel: The year of Heinrich III's birth: 1016. In: German Archives for Research into the Middle Ages 72 (2016), pp. 581–592 ( online ); Gerhard Lubich: Assessing the Emperor: Heinrich III. in historiography and historical research. In: Jan Habermann (Ed.): Kaiser Heinrich III. Government, Empire and Reception. Bielefeld 2018, pp. 21–31, here: p. 28 f.

- ↑ Via her mother Geberga, Gisela descended in the fourth degree from King Heinrich I, from whom Konrad descended in the fifth degree. The ecclesiastical marriage laws only forbade marriages in the ratio 4: 3, but some stricter standards were also applied.

- ↑ Wipo c. 2.

- ↑ Caspar Ehlers: Father and son in the travel kingdom of the early Salian empire. In: Gerhard Lubich, Dirk Jäckel (Eds.): Heinrich III. Dynasty - Region - Europe. Cologne et al. 2018, pp. 9–38, here: p. 10.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram : Konrad II. 990-1039. Emperor of three kingdoms. Munich 2000, p. 133.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram: Konrad II. 990-1039. Emperor of three kingdoms. Munich 2000, p. 47. See: MGH DD Ko II. 114ff .

- ^ MGH DD Ko II. 129 . Compare with Thomas Zotz: Spes Imperii - Heinrichs III. Rule practice and integration into the empire. In: Michael Borgolte (Ed.): Contributions to the honorary colloquium by Eckhard Müller-Mertens on the occasion of his 90th birthday. Berlin 2014, pp. 7-23 ( online ).

- ↑ Egon Boshof: The Salians . 5th, updated edition, Stuttgart 2008, p. 53.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram: The embassy of Conrad II to Constantinople (1027/29). In: Mitteilungen des Institut für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung 100, 1992, pp. 161–174; Herwig Wolfram: Konrad II. 990-1039. Emperor of three kingdoms. Munich 2000, pp. 215-221; Franz-Reiner Erkens : Konrad II (around 990-1039) rule and empire of the first Salier emperor. Regensburg 1998, pp. 113-116.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram: Konrad II. 990-1039. Emperor of three kingdoms . Munich 2000, p. 93.

- ^ Franz-Reiner Erkens: Konrad II. (Around 990-1039) rule and empire of the first Salier emperor. Regensburg 1998, p. 168.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: The Century of the Salians 1024–1125 . Ostfildern 2006, p. 54.

- ↑ Claudia Zey: Wives and Daughters of the Salic Rulers. On the change in Salic marriage policy during the crisis. In: Tilman Struve (Ed.): The Salians, the Reich and the Lower Rhine. Cologne et al. 2008, pp. 47–98, here: pp. 54 and 57 ff. ( Online ).

- ↑ Claudia Garnier : The culture of the request. Rule and communication in the medieval empire. Darmstadt 2008, p. 105.

- ↑ Wipo c. 39.

- ↑ Egon Boshof: The Salians . 5th, updated edition, Stuttgart 2008, p. 120.

- ↑ Claudia Zey: Wives and Daughters of the Salic Rulers. On the change in Salic marriage policy during the crisis. In: Tilman Struve (Ed.): The Salians, the Reich and the Lower Rhine. Cologne et al. 2008, pp. 47–98, here: pp. 54 and 57 ff ( online ); Mechthild Black-Veldtrup: Empress Agnes (1043-1077). Source-critical studies. Cologne et al. 1995, p. 63 ff.

- ^ Rudolf Schieffer: Heinrich III. 1039–1056 , in: Helmut Beumann (ed.), Kaisergestalten des Mittelalters, Munich 1984, pp. 98–115, here: p. 103.

- ↑ Friedrich Prinz: Emperor Heinrich III. and his contradicting judgment and reasons . In: Historische Zeitschrift 246 (1988), pp. 529-548.

- ↑ Following Prince's assessment: Stefan Weinfurter: Das Jahrhundert der Salier 1024–1125 . Ostfildern 2006, p. 111.

- ^ Daniel Ziemann: The difficult neighbor. Henry III. and Hungary. In: Gerhard Lubich, Dirk Jäckel (Eds.): Heinrich III. Dynasty - Region - Europe. Cologne et al. 2018, pp. 161–180, here: p. 180.

- ↑ Claudia Garnier: The culture of the request. Rule and communication in the medieval empire. Darmstadt 2008, p. 100.

- ↑ Annales Altahenses ad 1052.

- ↑ Egon Boshof: The Salians . 5th, updated edition, Stuttgart 2008, p. 157.

- ^ O regina poli, me regem spernere noli. Me tibi commendo praesentia dona ferendo, patrem cum matre, quin iunctam prolis amore, ut sis adiutrix et in omni tempore fautrix see to the translation. Stefan Weinfurter: order configurations in the conflict. The example of Henry III. In: Jürgen Petersohn (Ed.): Mediaevalia Augiensia. Research on the history of the Middle Ages. Stuttgart 2001, pp. 79-100, here: p. 86.

- ↑ Ante tui vultum mea defleo crimina multum. Da veniam, merear, cuius sum munere caesar. Pectore cum mundo, regina, precamina fundo aeternae pacis et propter gaudia lucis . see the translation: Stefan Weinfurter: Configurations of Order in Conflict. The example of Henry III. In: Jürgen Petersohn (Ed.): Mediaevalia Augiensia. Research on the history of the Middle Ages. Stuttgart 2001, pp. 79-100, here: p. 86.

- ↑ Lothar Born Scheuer: Misery Regum. Investigations into thoughts of crisis and death in the theological ideas of the Ottonian-Salic period. Berlin 1968.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: The last Salians in the judgment of their contemporaries . In: Christoph Stiegemann, Matthias Wemhoff (Hrsg.): Canossa 1077. Shock of the world . Munich 2006, pp. 79–92, here: p. 81.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Canossa. The disenchantment of the world . 2nd edition, Munich 2006, p. 32.

- ↑ Johannes Fried: Virtue and Holiness. Observations and reflections on the images of Henry III's rulers. in Echternach manuscripts. In: Wilfried Hartmann (Ed.): Middle Ages. Approaching a strange time . Regensburg 1993, pp. 41-85, here: p. 47.

- ^ Mechthild Black-Veldtrup: Empress Agnes (1043-1077). Source-critical studies . Cologne 1995, p. 117.

- ↑ Ludger Körntgen: Kingdom and God's grace. On the context and function of sacred ideas in historiography and images of the Ottonian-Early Salian period . Berlin 2001, p. 252.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: The Century of the Salians 1024–1125 . Ostfildern 2006, p. 90.

- ↑ Johannes Laudage: Heinrich III. (1017-1056). A picture of life. In: Das Salische Kaiser-Evangeliar, Commentary Vol. I. edited by Johannes Rathofer, Madrid 1999, pp. 87–200, here: p. 98.

- ↑ Such a formulation from the Annales Altahenses maiores, op. 1045.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: Legitimation of rule and the changing authority of the king: The Salier and their cathedral in Speyer . In: Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): Die Salier und das Reich Vol. 1: Salier, Adel und Reichsverfassungs . Sigmaringen 1991, pp. 55-96, p. 73.

- ↑ Hermann von Reichenau, Chronicon, a. 1052.

- ↑ Caspar Ehlers: Metropolis Germaniae. Studies on the importance of Speyers for royalty (751–1250). Göttingen 1996, p. 91 ff.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Configurations of order in conflict. The example of Henry III. In: Jürgen Petersohn (Ed.): Mediaevalia Augiensia. Research on the history of the Middle Ages . Stuttgart 2001, pp. 79-100, here: p. 99.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: The Century of the Salians 1024–1125 . Ostfildern 2006, p. 93.

- ↑ Egon Boshof: The Salians . 5th, updated edition, Stuttgart 2008, p. 126.

- ↑ Guido Martin: The Salic ruler as Patricius Romanorum. To the influence of Henry III. and Heinrichs IV. on the occupation of the Cathedra Petri , In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien, Vol. 28 (1994), pp. 257-295, here: p. 260.

- ↑ Guido Martin: The Salic ruler as Patricius Romanorum. To the influence of Henry III. and Heinrichs IV. on the occupation of the Cathedra Petri , In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien, Vol. 28 (1994), pp. 257-295, here: p. 264.

- ^ Egon Boshof, The Salians . 5th, updated edition, Stuttgart 2008, p. 131.

- ↑ Egon Boshof: The Salians . 5th, updated edition, Stuttgart 2008, p. 131

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: The Century of the Salians 1024–1125 . Ostfildern 2006, p. 96.

- ↑ Egon Boshof: The Salians . 5th, updated edition, Stuttgart 2008, p. 96.

- ↑ On this: Monika Suchan: Princely opposition to royalty in the 11th and 12th centuries as a designer of medieval statehood. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien, Vol. 37 (2003) pp. 141–165, here: p. 149.

- ↑ Fundatio monasterii Brunwilarensis ed. By Herman Pabst, NA 12 (1874), pp. 174-192, here: c. 8, p. 161.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter, The Century of the Salians 1024–1125 . Ostfildern 2006, p. 110. Also: Egon Boshof, Die Salier. 5th, updated edition, Stuttgart 2008, p. 96.

- ↑ Egon Boshof: The Empire in Crisis. Thoughts on the outcome of Henry III's government. In: Historische Zeitschrift 228 (1979), pp. 265–278, here: p. 282.

- ↑ Hermann von Reichenau, Chronicon, a. 1052.

- ^ Stefan Weinfurter: Canossa. The disenchantment of the world 2nd edition, Munich 2006, p. 44.

- ↑ Annales Altahenses a. 1055

- ↑ Fundatio monasterii Brunwilarensis ed. By Herman Pabst, NA 12 (1874), pp. 174-192, here: c. 8, p. 161.

- ↑ Ernst Steindorff: Yearbooks of the German Empire under Heinrich III. , Vol. 2 (1881 reprint 1969), pp. 321f.

- ↑ Florian Hartmann: And do the Saxons fight forever? Henry III. and the Duchy of Saxony. In: Gerhard Lubich, Dirk Jäckel (Eds.): Heinrich III. Dynasty - Region - Europe. Cologne et al. 2018, pp. 73–86, here: p. 85.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: The Billunger in the Salierzeit. In: Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): The Salians and the Empire. Sigmaringen 1990, Vol. 3, pp. 309-329, here: p. 319.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: The Billunger in the Salierzeit. In: Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): The Salians and the Empire. Sigmaringen 1990, Vol. 3, pp. 309-329, here: p. 309.

- ↑ Adam III, Aug.

- ↑ Florian Hartmann: And do the Saxons fight forever? Henry III. and the Duchy of Saxony. In: Gerhard Lubich, Dirk Jäckel (Eds.): Heinrich III. Dynasty - Region - Europe. Cologne et al. 2018, pp. 73–86, here: p. 78.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: Legitimation of rule and the changing authority of the king: The Salier and their cathedral in Speyer. In: The Salians and the Empire, Vol. 1 . Sigmaringen 1991, pp. 55-96, here: p. 84.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: The Billunger in the Salierzeit. In: Stefan Weinfurter (Ed.): The Salians and the Empire . Sigmaringen 1990, Vol. 3, pp. 309-329, here: pp. 320 f.

- ↑ Chronicle of the Petershausen Monastery, Book 2, cap. 31.

- ↑ See Tillmann Lohse: The duration of the foundation. A diachronic comparative history of the secular collegiate monastery St. Simon and Judas in Goslar. Berlin 2011, pp. 45–71.

- ↑ Adam III, Aug.

- ↑ Adam III, 5.

- ↑ Hermann von Reichenau, Chronicon, a. 1044

- ^ Egon Boshof: Lorraine, France and the empire in the reign of Henry III. , In: Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter . Vol. 42 (1978), pp. 63-127, here: p. 66.

- ^ Egon Boshof: Lorraine, France and the empire in the reign of Henry III. , in: Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter, Vol. 42 (1978), pp. 63–127, here: p. 69.

- ↑ Annales Altahenses ad 1044.

- ^ Egon Boshof: Lorraine, France and the empire in the reign of Henry III. In: Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter . Vol. 42 (1978), pp. 63-127, here: p. 75.

- ^ Egon Boshof: Lorraine, France and the empire in the reign of Henry III. In: Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter. Vol. 42 (1978), pp. 63-127, here: p. 78.

- ^ Egon Boshof: Lorraine, France and the empire in the reign of Henry III. In: Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter. Vol. 42 (1978), pp. 63-127, here: pp. 89f.

- ↑ Stefan Weinfurter: The Century of the Salians 1024–1125 . Ostfildern 2006, p. 107.