Besançon

| Besançon | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| region | Bourgogne-Franche-Comté ( Prefecture ) | |

| Department | Doubs | |

| Arrondissement | Besançon | |

| Canton |

Chief lieu of six cantons |

|

| Community association | Grand Besançon Métropole | |

| Coordinates | 47 ° 15 ' N , 6 ° 1' E | |

| height | 235-610 m | |

| surface | 65.05 km 2 | |

| Residents | 115,934 (January 1, 2017) | |

| Population density | 1,782 inhabitants / km 2 | |

| Post Code | 25,000 | |

| INSEE code | 25056 | |

| Website | http://www.besancon.fr/ | |

Besançon |

||

Besançon [ bəzɑ̃ˈsõ ] (German obsolete Bisanz, Latin Vesontio ) is a city with 115,934 inhabitants (as of January 1, 2017) in the east of France . It is the administrative seat of the Doubs department , was the capital of the Franche-Comté region and is the seat of the Archdiocese of Besançon . The inhabitants of the city are called Bisontines / Bisontins . The population of Besançon is 244,448.

The place, which was founded in a loop of the Doubs river , played an important role during the time of the Roman Empire under the name Vesontio . In the Middle Ages, Besançon succeeded in gaining and maintaining its status as a free city in the Holy Roman Empire . During the 17th century, the region of what is now Franche-Comté was fiercely contested; Besançon has only been part of France since 1678. After the French conquest, the city was heavily fortified. In the course of industrialization , Besançon became the center of the French watch and textile industry. To this day, the city is a leader in the fields of micro and nanotechnology.

The capital of Franche-Comté, which has been named the “greenest city in France”, offers an extraordinarily high quality of life. Thanks to its rich historical and cultural heritage and unique architecture, Besançon has been a City of Art and History since 1986 . Its military fortifications , which go back to Vauban , have been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2008 .

geography

location

Besançon lies on the Rhine-Rhône axis, an important connecting route between the North Sea and the Mediterranean or between northern and southern Europe. The city is located where the massif of the Jura Mountains merges into the fertile Franche-Comté plain . It lies on the northern edge of the Jura; north of the city is a range of hills belonging to the promontory (Avants-Monts). South of Besançon is the first fold of the Jura. The city is traversed by the Doubs River and is located in the northwest of the department of the same name . The neighboring cities of Dijon in Burgundy , Lausanne in Switzerland, Belfort at the foot of Alsace and the border with Germany are all 90 kilometers from Besançon. The French capital Paris is 327 kilometers (as the crow flies) away. Besançon is almost exactly halfway between the cities of Lyon and Strasbourg ; the distance to both is about 190 kilometers.

Since 2004 Besançon has formed the Métropole Rhin-Rhône together with the cities of Dijon , Mulhouse , Belfort , Montbéliard , the trinational Eurodistrict Basel , Le Creusot - Montceau-les-Mines , Chalon-sur-Saône and Neuchâtel . Besançon has been a member of the Pôle métropolitain Center Franche-Comté together with some neighboring cities since 2012 .

City structure

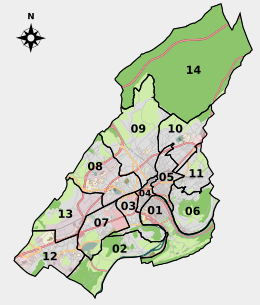

Besançon has 14 districts with a population of around 2,200 (Tilleroyes and Velotte) to just under 20,000 (Planoise) (2006 population in brackets); the numbers refer to the adjacent card:

- 01 Center (La Boucle and Saint-Jean), Chapelle des Buis (11.232)

- 02 Velotte (2,227)

- 03 Grette-Butte (9,311)

- 04 Battant (4,200)

- 05 Chaprais (14,969)

- 06 Bregille-Pres-de-Vaux (3,244)

- 07 Saint-Ferjeux-Rosemont (6,457)

- 08 Montrapon-Fontaine-Écu-Montboucons-Temis (12,745)

- 09 Saint-Claude-Torcols (14,521)

- 10 Palente-Orchamps-Saragosse (11,190)

- 11 Vaites-Clairs-Soleils (5,498)

- 12 Planoise-Châteaufarine-Hauts du Chazal (19.309)

- 13 Tilleroyes-Trépillot (2,178)

- 14 Chailluz

Neighboring communities

The following municipalities border the municipality of Besançon; clockwise, starting in the north, they are called: Châtillon-le-Duc , Bonnay , Vieilley , Mérey-Vieilley , Braillans , Thise , Chalezeule , Montfaucon (Doubs) , Morre , Fontain , Beure , Avanne-Aveney , Franois , Serre- les-Sapins , Pirey , École-Valentin .

Metropolitan area

The municipalities of Besançon, Avanne-Aveney , Beure , Chalezeule , Chalèze , Châtillon-le-Duc , Devecey , École-Valentin , Miserey-Salines , Pirey and belong to the residential unité urbaine of Besançon, in which a total of 134,376 inhabitants live on 122 km² Thise .

In 1999, 222,381 people in 234 municipalities lived in the Aire urbaine , a geographical economic area , in a metropolitan area stretching over 1,652 km².

climate

The climate of Besançon has oceanic influences in the form of abundant and frequent rainfall on the one hand and continental influences on the other hand, which manifest themselves in harsh winters and dry and hot summers. There are strong fluctuations both from one season to another and between years. With 1108 mm of precipitation per year, Besançon is one of the rainier cities in France, along with Brest and Biarritz . Every year there is an average of 141 days of precipitation, of which around 30 days are snow. Despite this, Besançon has 1797 hours of sunshine per year, which fluctuate between 55 a month in December and 246 in August. The temperature is below freezing 67 days a year. Besançon has relatively little wind. The average wind speed is 2.2 m / s, gusts over 100 km / h only occur once a year. The highest temperature ever measured is 40.3 ° C on July 28, 1921, the lowest temperature at −20.7 ° C on January 9, 1985. The annual average temperature is 10.2 ° C.

|

Average temperatures and rainfall for Besançon, 1971–2000

Source: Météo France

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

history

Besançon developed from a Gallic oppidum into one of the cultural, military and economic centers of today's France. Due to the large number of historically valuable artefacts, both of Germanic and French origins, the city is allowed to carry the title City of Art and History .

Prehistory to antiquity

The presence of hunters and gatherers in the region is documented for the Middle Paleolithic (around 50,000 years ago) . Excavations carried out in the past centuries have unearthed traces of settlement from the Neolithic Age . The banks of the Doubs , the foot of the Roche d'Or and Rosemont hills were mainly settled . The finds were dated to 4000 BC. Dated.

In the 2nd century BC Today's Besançon was under the rule of the Sequani . These Celtic people controlled a large territory between the Rhône , the Saône , the Jura and the Vosges . A series of excavations in the area of the former city wall, especially in 2001, has shown that the settlement was enclosed by a wall (murus gallicus) ; however, the craftsmen settled outside the wall. The oppidum, called Vesontio in Latin, was the main town and economic center of the Sequani. It was threatened by the Teutons and in 59 BC. BC, perhaps even earlier, conquered by the Suebi under Ariovistus , later by the Haeduer and in 58 BC. Finally by the Romans under Julius Caesar . Because of its strategically favorable location, Caesar chose the city as the main town of the Sequans (Civitas Maxima Sequanorum). Vesontio became a military base and trading hub of Roman Gaul; it flourished during which it grew into one of the largest cities of Gallia Belgica and later Germania superior .

In AD 68, the region was the scene of the Battle of Vesontio , in which Lucius Verginius Rufus , the emperor Nero was devoted, and the rebel Gaius Iulius Vindex faced each other. The latter committed suicide after his defeat. The Romans enlarged the city and built numerous structures, especially along the Cardo (today's Grande Rue ) and also on the right side of the Doubs, where they built an amphitheater with space for 20,000 visitors. In the underground of Besançon there are numerous artefacts from the Roman era, especially within the Doubs loop and in the immediately adjacent areas, where more than 200 sites exist. From the time of Marcus Aurelius , buildings such as the Porte Noire , built around 175 AD, the columns of Square Castan , the aqueduct that supplied the city with water, the amphitheater and Roman houses with mosaics, which are now in the Musée des beaux-arts et d'archéologie de Besançon are on display; between 172 and 175 there were also riots. During the Tetrarchy , Vesontio was raised to the capital of the Provincia Maxima Sequanorum . In 360, however, the passing Emperor Julian referred to the city as a market town, which indicates a decline; Besançon was now just a village.

middle Ages

Shortly after the fall of the Roman Empire, the Gallic peoples were united under the Merovingian king Clovis I. The Sequani were incorporated into the Franconian Empire at the same time as the Burgundians and the Alamanni .

The history of Besançon in the early Middle Ages has been little researched, and documents and other references are largely missing. The city is first mentioned in a letter from Louis le Pieux to Archbishop Bernoin in 821; here Besançon was called Chrysopolis . From 843 to 869 the diocese of Besançon was part of Lotharii Regnum , later of Lotharingien and after the death of Lothar II , Charles the Bald took possession of it on the basis of the provisions of the Treaty of Meerssen (870). Until 879 it was part of the west of France .

In 888 Odo of Paris feudalized his empire and founded the duchies and counties of Burgundy . At that time, Burgundy had Dole as its capital and belonged to the county of Varais , where Besançon was also located. The first Count of Burgundy was Otto-Wilhelm , the Count Palatine . At the same time Besançon became an independent archbishopric and episcopal seat, whereby it became a tradition that the archbishop also became chancellor of the king of Burgundy. The last king of Burgundy, Rudolf III , had no male successors and gave his possessions to Henry II as a fief.

Thus Besançon and the entire Free County of Burgundy became part of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation in 1032 . Archbishop Hugo von Salins also becomes master of the city with imperial support, which he leads into a blooming phase. After his death in 1066, however, she fell into a long crisis caused by succession struggles. However, throughout the Middle Ages, Besançon remained a city under direct imperial rule and which remained independent from the county of Burgundy.

In the 12th and 13th centuries, the Bisontines defied the power of the archbishops and finally obtained their urban independence in 1290 . Besançon remained part of the German Empire, but governed itself with a council of 28 civil servants, who were directly appointed by the male electorate, and a council of 14 governors who were elected by these civil servants. Besançon retained this status of a free city for almost 400 years. The Free Counts of Burgundy , who had gained control of Franche-Comté , became the protective power for the free city, which became prosperous during this period.

Modern times

After the death of Charles the Bold Besançon was from Louis XI. promoted. At the beginning of 1481 he not only confirmed the town charter, but also ordered the transfer of the University of Dole to Besançon. The driving force behind these developments was Charles of Neuchâtel , Archbishop of Besançon and advisor to Louis XI.

With the beginning of the Renaissance, Franche-Comté fell back to the German Empire. Emperor Charles V fortified Besançon and turned the city into a bulwark for his empire. A Comtois, Nicolas Perrenot de Granvelle , became Imperial Chancellor in 1519 and Minister of Justice in 1532. The region benefited from Charles V's benevolence, Besançon grew to become the fifth largest city in the empire and received several architectural monuments such as the Granvelle Palace and the town hall, the facade of which is still adorned by a statue of Charles V today. The population, which in 1518 numbered 8,000–9,000 people and in 1608 11,000–12,000 people, more than half lived from viticulture, which became the city's most important industry. The Cabordes de Besançon, which have been preserved to this day, date from this period .

While the 16th century was marked by prosperity, the 17th century was a period of war and hardship. From 1631 the city twice hosted Gaston de Bourbon , brother of the king and personal enemy of Cardinal Richelieu . During the Ten Years War , which raged in Franche-Comté as part of the Thirty Years War , plague and famine raged in the region. Besançon escaped sieges several times, but the plague broke out in 1636 and from 1638 to 1644 the population of the city suffered from starvation.

From 1651 negotiations were in progress about an exchange contract: Philip IV , King of Spain, should cede the city of Frankenthal to the German Empire and get Besançon in return. The Bisontines only approved this plan in 1664. In order to found a new bailiwick, 100 villages had to be added to the city. For a ten-year period, Besançon lost its free city status and became Spanish property. However, the peace was short-lived: on February 8, 1668, the army of the Grand Condé marched into Besançon after the local authorities had surrendered. On June 9th, however, the French had to retreat. Fortification work began that same summer: the foundation stone for the citadel was laid on September 29, 1668 and extensive work was carried out on the other side of the city around Charmont.

On April 26, 1674, a force of the Prince of Condé , which numbered 15,000-20,000 men and was supported by Vauban , marched on in front of Besançon to besiege and take it. In order to force a quick conquest of the city, Vauban had a large artillery of 36 cannons carried to Mont Chaudanne during the night . After a 27-day siege, which King Louis XIV attended at the Château de Marnay as well as Louvois , the fortress fell into the hands of the besiegers on May 22nd. Besançon was subsequently raised to the capital of Franche-Comté with the patents of October 1, 1677 at the expense of Dole. Step by step, numerous authorities such as the military government, the economic administration, the parliament or the university were settled in Besançon. The Treaty of Nijmegen , signed on August 10, 1678, finally annexed the city and its surrounding area to France.

Louis XIV decided to develop Besançon into a bulwark of his eastern defense and entrusted Vauban with carrying out the necessary construction work. The citadel was completely rebuilt between 1674 and 1688, further fortifications followed in 1689–1695 and numerous barracks were built from 1680 onwards. The construction of the fortress was so expensive that Louis XIV is said to have asked whether the walls were made of gold.

In the 18th century, thanks to capable administrators, Franche-Comté experienced a period of prosperity, during which the population of Besançon grew from 14,000 to 32,000 inhabitants and monuments and magnificent buildings were built.

As a result of the French Revolution , Besançon lost its status as the seat of the archbishop and as the capital. It was now nothing more than the capital of a department from which the most agriculturally productive areas - those in the lowlands - had been separated. The population, which had been around 32,000 before the revolution, fell to 25,328 in 1793, recovering slightly to 28,423 by 1800. At the same time, however, the watch industry settled in the city: in 1793 a group of Swiss watchmakers around Laurent Mégevand , who had been expelled from Switzerland for his political activities, founded a watch manufacture in Besançon. Although part of the population of Besançon was not friendly to the watchmaking trade, 14,700 watches were made in 1794/95, and in 1802/03 there were already 21,400.

During the Third Republic , Besançon experienced stagnation, and the population fluctuated around 55,000 for several decades. The watch industry developed independently of this, with production increasing to 395,000 watches in 1872 and 501,602 in 1883. In 1880 90% of the watches made in France came from Besançon, where 5000 master watchmakers and 10,000 piece workers were employed in this branch. The pressure of Swiss competition plunged the Besançon watchmaking into a crisis, from which the sector recovered at the beginning of the 20th century: 635,980 watches were produced in 1900, and the number of employees fell to around 3,000 by 1910. At the same time, others developed Branches of the economy such as the brewing industry (with Gangloff being the most famous company in the industry), paper production and metal processing. However, the textile industry developed most dynamically after Hilaire de Chardonnet developed a method of making artificial silk and allowed the city to use this method in a factory that opened in Prés-de-Vaux in 1891 . From June to October 1860, the International Exhibition 1860 was held on Place Labourey (today's Place de la Révolution) to promote watchmaking on the one hand and local handicrafts on the other. At the end of the 19th century Besançon also became a seaside resort: in 1890 the Compagnie des Bains Salins de la Mouillère was founded, and tourism developed around the Besançon-les-Bains brand , which included a thermal bath , a hotel and a casino Kursaal and in 1896 a tourist association was established. In 1910, Besançon was hit by the worst flood to date .

Second World War

At the beginning of the Second World War , the German army marched into Besançon on June 16, 1940, although the French military had blown up all bridges before the advancing enemy. After the invasion, Besançon became part of France intended for German settlement, with the demarcation line only 30 km west of the city. In the event of a German victory in World War II, Besançon would have become part of the German Empire. Until the bomb attack by the British Air Force on the night of July 15-16, 1943, in which a bomber fell on the station and left 50 dead and 40 seriously injured, the city had been spared major destruction. The Resistance became active relatively late in Besançon: the first assassinations were carried out in the spring of 1942. The Germans responded with arrests, and on September 26, 1943, 16 members of the Resistance were executed in the Citadel of Besançon . 83 more suffered the same fate as a result. On September 6, 1944, Besançon was retaken by the American 3rd and 45th Infantry Divisions, which had landed in Provence . The 6th Corps of the American Army marched into Besançon on September 8, 1944 after a four-day battle, and General Charles de Gaulle visited the liberated Besançon on September 23, 1944. The best-known members of the Resistance in Besançon include Gabriel Plançon , Jean and Pierre Chaffanjon , Henri Fertet , the Mercier brothers , Raymond Tourrain , Marcelle Baverez , Henri Mathey and Father Robert Bourgeois .

post war period

After the end of the war, Besançon, like all of France, experienced a strong economic boom. The population grew particularly rapidly, it increased by 38.5% between 1954 and 1962, which was only exceeded by Grenoble and Caen . The infrastructure was only able to keep up with this development with a delay: in 1970 the rail link to Paris was electrified, the Rhine-Rhône Canal expanded from 1975 and Besançon only got a motorway connection in 1978 . The idea of building an airport in La Vèze was quickly abandoned.

The watch industry initially remained dominant, but lost its importance at the expense of more dynamic industries such as the textile, construction and food industries. In 1954, 50% of industrial jobs were in watchmaking, but this proportion fell to 35% by 1962. In 1962, three companies had more than 1,000 employees: the watch manufacturers Lip and Kelton-Timex and the textile manufacturer Rhodiacéta . However, Besançon remained the center of watchmaking in France, as it housed corporate headquarters and research and development departments. At the same time, the textile industry experienced an upswing: Rhodiacéta had 3,300 employees in 1966 and the family business Weil had 1,500 employees in 1965 and was France's leading manufacturer of men's clothing.

In view of this exponential growth and in particular the shortage of housing, the city administration decided to build the residential districts Montrapon-Fontaine-Écu and Palente - Orchamps from 1952 , and from 1960 the three 408 buildings named after the number of apartments. These quarters were mainly inhabited by industrial workers. The weaknesses of this model became apparent very quickly and between 1961 and 1963 the systems had to be modernized and expanded. At the same time, the new Planoise district, the two industrial areas Palente and Trépillot and the Bouloie campus were set up. Three connecting roads were also built to speed up traffic. With a decree of June 2, 1960, which established regions, Besançon became the regional capital.

Crisis and realignment

The 1973 oil crisis marked the end of the boom for Besançon and the beginning of an economically difficult period. This crisis is best symbolized by the Lip affair , which is still having an impact today: the watch manufacturer Lip had to submit a dismissal plan in the spring of 1973, which resulted in a labor dispute based on self-management and solidarity-based economy and a wave of solidarity that resulted in a demonstration of 100,000 people in an otherwise deserted city. After resuming operations in the meantime, the company finally had to file for bankruptcy in 1977. The Rhodiacéta plant closed in the early 1980s and that of Kelton-Timex shortly thereafter. In the 1990s, the textile manufacturer Weil relocated its production and drastically reduced its workforce. Thus around 10,000 jobs in the city were lost within 20 years. Since then, Besançon has been restructured from an industrial to a service economy, which has been encouraged by the decentralization policy that France has been pursuing since 1982. The know-how that Besançon has built up over two centuries of watchmaking has been successfully used to become an international leader in areas such as microtechnology , precision mechanics and nanotechnology . The high quality of life, the cultural heritage and the convenient location in terms of transport have further contributed to a renewed economic upturn.

population

The city of Besançon had 116,914 inhabitants as of January 1, 2010, making it the 30th largest city in France. Since 1975, when the population of the city reached its maximum of 120,315, it has therefore shrunk slightly. Compared to other French regional capitals, Besançon is a rather small city. Its metropolitan area, in which 244,449 inhabitants live, is, however, the largest in Franche-Comté, ahead of the agglomerations around the cities of Montbéliard (162,650 inhabitants) and Belfort (112,693 inhabitants). Population censuses have been carried out regularly in the city since 1793.

| year | 1793 | 1800 | 1806 | 1821 | 1831 | 1836 | 1841 | 1846 | 1851 | 1856 | 1861 | 1866 | 1872 | 1876 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residents | 25 328 | 28 436 | 28 727 | 26 388 | 29 167 | 29 718 | 36 461 | 39 949 | 41 295 | 43 544 | 46 786 | 46 961 | 49 401 | 54 404 |

| year | 1881 | 1886 | 1891 | 1896 | 1901 | 1906 | 1911 | 1921 | 1926 | 1931 | 1936 | 1946 | 1954 | 1962 |

| Residents | 57 067 | 56 511 | 56 055 | 57 556 | 55 362 | 56 168 | 57 978 | 55 652 | 58 525 | 60 367 | 65 022 | 63 508 | 73 445 | 95 642 |

| year | 1968 | 1975 | 1982 | 1990 | 1999 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2016 | |||

| Residents | 113 220 | 120 315 | 113 283 | 113 828 | 117 733 | 117 080 | 117 836 | 117 599 | 117 392 | 116 914 | 116 466 | |||

| Sources: Cassini and INSEE From 1962: only main residences. | ||||||||||||||

politics

mayor

|

|

Municipal council

The Besançon City Council currently has 55 members.

The election to the municipal council on June 28, 2020 led to the following result:

| Party / list | percent | Seats |

|---|---|---|

| Anne Vignot ( The Greens - PS - PCF ) | 43.8 | 40 |

| Ludovic Fagaut ( LR ) | 41.6 | 11 |

| Eric Alauzet ( LREM ) | 14.6 | 4th |

coat of arms

Description: A black eagle on gold (imperial city), holding a red column in its claws on both sides .

Town twinning

-

Huddersfield , Kirklees ( England ), since 1955/1995

Huddersfield , Kirklees ( England ), since 1955/1995 -

Freiburg im Breisgau ( Germany ), since 1959

Freiburg im Breisgau ( Germany ), since 1959 -

Hadera ( Israel ), since 1964

Hadera ( Israel ), since 1964 -

Pavia ( Italy ), since 1964

Pavia ( Italy ), since 1964 -

Neuchâtel ( Switzerland ), since 1975

Neuchâtel ( Switzerland ), since 1975 -

Douroula ( Burkina Faso ), since 1985

Douroula ( Burkina Faso ), since 1985 -

Kuopio ( Finland ), since 1986

Kuopio ( Finland ), since 1986 -

Bistrița ( Romania ), since 1990

Bistrița ( Romania ), since 1990 -

Man ( Ivory Coast ), since 1991

Man ( Ivory Coast ), since 1991 -

Bielsko-Biała ( Poland ), since 1993

Bielsko-Biała ( Poland ), since 1993 -

Tver ( Russia ), since 1996

Tver ( Russia ), since 1996 -

Aqabat Jabr , Palestinian Territories (near Jericho ), since 2004

Aqabat Jabr , Palestinian Territories (near Jericho ), since 2004 -

Charlottesville , Virginia ( United States ), since 2006

Charlottesville , Virginia ( United States ), since 2006

Economy and Infrastructure

traffic

In ancient times, Besançon was on a Roman road that was called Via Francigena from the Middle Ages . In addition to Besançon, it ran through Calais , Reims , Lausanne and Aosta; it was part of a route connecting Rome to the North Sea .

Today, as in most European cities, traffic is determined by the car and road traffic is constantly increasing. The city is connected to the French and international motorway network with the A36 (La Comtoise) Dole – Belfort motorway , which runs north of the Besançon area. The national road N 57 connects Besançon with Metz, Nancy and Switzerland, the N 83 with the important cities of Lyon and Strasbourg . For a long time, attempts have been made to relieve traffic in the city center by means of a bypass road. The northeast section (Voie des Montboucons) has been completed since 2003, the southwest section (Voie des Mercureaux) was opened to traffic on July 11, 2011.

The rail connection was greatly upgraded with the opening of the LGV Rhin-Rhône on December 11, 2011. Since then, TGVs have connected the Besançon Franche-Comté TGV station outside the city and, less frequently, the Besançon-Viotte station near the city center with Paris (travel time 2 hours), Lyon (1:55 hours) and Strasbourg (1:30 hours). The opening of this high-speed route has also made direct connections possible with other large cities such as Zurich , Frankfurt am Main , Lille or Marseille . The west and south sections of this line (between Genlis and LGV Sud-Est or between Dole and Bourg-en-Bresse ) are in planning and should go into operation by around 2020. The Besançon-Viotte city railway station is on the Dole – Besançon – Belfort railway line and is also the junction of the Bourg-en-Bresse – Besançon and La Chaux-de-Fonds – Le Locle – Besançon railway lines that end here, as well as the partially closed Vesoul – Devecey– Besançon . The latter was partially reactivated and now serves as a feeder to the new Besançon Franche-Comté TGV station. TER trains run from Viotte and Besançon-la Mouillère train station to Belfort , Montbéliard , Dole, Dijon , Morteau , Lons-le-Saunier , Bourg-en-Bresse and Switzerland.

The Rhine-Rhône Canal , which runs through Besançon, is only used by excursion boats. An expansion of this waterway, which would also allow commercial use, was rejected in 1997, although this project is sometimes being discussed again. Aviation is just as insignificant in Besançon: there are two airports in the neighboring municipalities of the city, namely the Aérodrome de Besançon-La Vèze and the Aérodrome de Besançon-Thise . The closest airports are Geneva , Lyon and Basel .

City traffic is u. a. operated by buses: Veolia Transdev's network, called Ginko , consists of 19 city and 30 regional lines. A quarter of the fleet is powered by natural gas for environmental reasons. The old Besançon tram was discontinued in 1952, a new line went into operation on August 30, 2014. Besançon pioneered the establishment of a pedestrian zone in 1974. A free bike rental system called VéloCité has existed since 2007 and a car sharing service (Auto'cité) since 2010 .

economy

In Besançon, Hilaire de Chardonnet opened the first commercial rayon spinning mill in 1889, whose products were drawn and spun from collodion . This invention came about as a response to the devastating silkworm plague on the mulberry plantations in the Lyon region , at the time the center of French silkworm breeding.

The main industries today are microtechnology and watchmaking. There are also textile and metal processing companies. The Besançon area is known for its dairy products, especially cheese (Comté and Morbier). In Besançon there is a large plant in which important components of the high-speed train TGV are manufactured.

media

- France 3 Bourgogne - Franche-Comté: TV

- L'Est Républicain: Newspaper

Education and Research

The University of Franche-Comté , headquartered in Besançon, has around 21,000 students.

There are also five grammar schools, eleven other high schools and 39 elementary schools in the city.

Religions

Christianity is the main religion in the city. It was introduced to the region by Saints Ferreolus and Ferrutio from the third century onwards, although this view is not undisputed. After the two preachers had been tortured and beheaded, the first church was built with today's Cathedral of Besançon . After that, numerous other churches emerged over time, until the reform and the separation of state and religion broke the omnipotence of the Catholic Church in Franche-Comté. From 1793 the Protestants, who had been expelled in 1575, began to settle again in Besançon as watchmakers. The city dedicated the Chapelle du Refuge in the Hôpital Saint-Jacques in 1793, the Champs Bruley cemetery in 1803 and the Couvent des Capucins chapel in 1805 (later destroyed). The main Protestant church is now the Chapelle du Saint-Esprit , consecrated in 1842 . In the 20th century, numerous other Christian groups came to the city with the Orthodox Protestant churches of various currents, the Jehovah's Witnesses and the Mormons. The Catholic Church today suffers from low visitor numbers in its churches, but remains the denomination with the greatest professorship among the Bisontins.

In terms of the number of believers, Islam is the second most important religion in Besançon: the proportion of Muslims in the population is estimated at 13% or 15,000 people. Islam came to the region from the 1870s when soldiers from the French colonies were stationed on France's eastern border to fight against Germany in the wars. They stayed until after the Second World War. The actual immigration from North Africa began in the 1960s, and the immigrants gradually built up their own religious community. At the end of the 1990s, the Mosquée Sunna de Besançon, the first mosque to be inaugurated, has since been joined by several other houses of prayer.

The history of the Jews in Besançon begins in the Middle Ages when trade in the city gave rise to a Jewish community. The Jews were expelled from the city in the 15th century after being tolerated for a long time. After the French Revolution, the Jewish community returned, established a Jewish cemetery in 1796 and built a synagogue in the Moorish style in Battant, which still exists today as the synagogue of Besançon . The Jewish community took part in the fighting of World War I, and fell victim to the Holocaust in World War II . The Jewish community has regained its strength through immigration, especially from North Africa, and the services in the synagogue are now held according to the Sephardic rite.

With immigrants from Asia, Buddhism also came to Besançon in the 1970s. In the 1980s, a Cambodian fat cat even came annually to hold ceremonies and guide the believers. A Buddhist center was established to build a pagoda in Planoise. Although there are many Buddhist religious associations, this religion has remained a minority phenomenon in Franche-Comté.

Culture and sights

Architectural heritage from ancient times

In ancient times, Besançon was called Vesontia and was an important city in Gaul , conquered by the Romans . Monumental buildings were erected in it, some of which have been preserved. Accidental archaeological finds in excavations often bring new finds from this era to light.

The best-known and best-preserved building from Roman times is the Porte Noire , a Gallic-Roman triumphal arch built under Marcus Aurelius in what is now the Saint-Jean district. It underwent a lengthy and laborious restoration at the beginning of the 21st century after the ravages of time and environmental pollution had damaged it. Exactly opposite the Porte Noire is the Square Castan , an ensemble of archaeological finds from the 2nd or 3rd century, which is surmounted by eight Corinthian columns .

On the other side of the Doubs , in the Battant district, the traces of the Vesontio amphitheater can be seen. However, only a few steps and foundation walls are preserved today, as the stones were used in the construction of other buildings in the Middle Ages. In Besançon, traces of two Roman houses have also been found in the former residential area of Vesontio: the Domus du Palais de Justice and the Domus du collège Lumière , whose mosaics are exhibited on the sites themselves and in the Musée des beaux-arts et d'archéologie de Besançon . Excavation finds in a less prominent place are, for example, ancient foundations in the underground car park of the Conseil régional de Franche-Comté .

Military architectural heritage

Most of today's fortification system (citadel, selection of city walls, bastions and the FG) is the work of Vauban . With this ensemble Besançon is represented on the list of world cultural heritage of UNESCO . The fortifications on the other hills were built in the 19th century, while structures from the time before Vauban's work have survived to this day.

The Citadel of Besançon was built between 1678 and 1771 according to plans by Vauban. With 250,000 visitors annually, it is the most visited place in Franche-Comté . It extends over 11 hectares on the summit of Mont Saint-Étienne at an altitude of 330–370 m above sea level and dominates the meander loop of the Doubs, which is 240–250 m. Today it houses the Resistance and Deportation Museum , a museum about life in Franche-Comté, the regional archaeological office and a zoo. It is the symbol of Besançon. The Fort Griffon, the name of its builder, the Italian architect Jean Griffoni received, which was entrusted in 1595 with the construction work, serving as a second citadel. It was completely rebuilt by Vauban and sold by the army in 1947. It has since hosted a school and the IUFM .

The system of fortifications around the La Boucle district, which were rebuilt between 1675 and 1695, is known as the city wall of Vauban . Vauban replaced the medieval fortifications, which were repaired and expanded under Charles V , with a belt with six fortified cannon towers, namely Tour Notre-Dame, Tour bastionnée de Chamars, Tour bastionnée des Marais, Tour bastionnée des Cordeliers (completed in 1691), Tour bastionnée de Bregille and Tour bastionnée de Rivotte .

There are also facilities that date back to before the French conquest. The Tour de la Pelote, which is located in today's Quai de Strasbourg , was built in 1546 on the instructions of Charles V by the city government. It owes its name to Pierre Pillot , Lord of Chenecey , to whom the land on which the tower was built belonged. The Porte Rivotte, which dates from the 16th century, consists of two round towers, one of which has an ornamental pediment with a sculpture of the sun by Louis XIV . The Porte Taillée, which was dug into a rocky ravine, dates back to the Romans. It is located at the entrance to the city from the direction of Switzerland. Above the Porte Taillée there is a guardhouse and a peeping tower, which were built in 1546. The Tour Carrée, which is now in the Promenade des Glacis , is also called Tour de Battant or Tour Montmart and dates back to 1526.

In the 19th century, more fortifications were built that cover all the elevations around the city. The Fort de Chaudanne (official name Fort Baudrand ) was built between 1837 and 1842, the Fort de Bregille (official name Fort Morand ) in the years 1820-1832 , the Fort de Planoise (official name Fort Moncey ) in the years 1877-1880 . The latter is used today by the Compagnons d'Emmaüs . The Fort Benoît was built from 1877 to 1880 and the Fort de Beauregard in 1830. The Fort Tousey and the Fort des Trois Châtels are Lunettes d'Arçon called round turrets with conical roofs, which in the late 18th and early 19th Century were built. A third Lunette d'Arçon is located within the walls of Fort de Chaudanne, but it was damaged during the fort's construction at the end of the 19th century. Furthermore, the Fort de Rosemont (built during the war 1870–1871), the Fort des Montboucons (built 1877–1880) and the Fort des Justices (from 1870) are noteworthy.

The Caserne Ruty, formerly called Caserne Saint-Paul , consists of four buildings that enclose a roll call square and date from the 18th and 19th centuries. Here today are the General Staff of the 7th Tank Brigade and Force No. 1 of the French land forces housed.

Religious buildings

Numerous churches and abbeys were built in Besançon since the third century and especially in the High Middle Ages after the city became the seat of a diocese. The city experienced high points of construction activity in the ninth century, when Hugo I von Salins held the office of bishop, and after the annexation by France in 1674. In 1842, the Église du Saint-Esprit ("Holy Spirit Church") became the Center of the Protestant community, in 1869 the Jews inaugurated their synagogue . Mosques have also been built in the city since the end of the 20th century.

The most important building dedicated to the Catholic faith is the Cathedral of St. John (cathédrale Saint-Jean), an example of Gothic architecture that was built or expanded in the 9th, 12th and 18th centuries. It has two absiden and houses the painting Vierge aux Saints from 1512, one of Fra Bartolommeo's main works . The cathedral towers over the former cathedral district, where the seat of the Archdiocese of Besançon is in the former Hôtel Boistouset . Here is also the old archbishop's palace , which today serves the rectorate of the academy . The Grand Séminaire was built between 1670 and 1695 under Archbishop Antoine-Pierre I von Grammont and completed in the 18th century with the construction of a portal and the residential building in front . Its chapel has an elegant facade with Corinthian pilasters on two floors. A tympanum with a virgin and child by the sculptor Huguenin from 1848 sits enthroned on its portal .

Apse of the Saint-Jean cathedral

Portal of the Saint-Jean cathedral

Church Saint-Pierre

Church Sainte-Madeleine

Saint-Maurice Church

Notre-Dame-du-Foyer chapel

At the other end of the old Cardo and today's Grande Rue is the Sainte-Madeleine church . which was built 1746–1766 according to plans by Nicolas Nicole . With the construction of the two towers from 1828 to 1830, it was finally completed. One of the two towers houses the famous Jacquemart bell ringer machine . The roof consists of colored glazed roof tiles.

In the actual city center stands the Saint-Pierre church, which was built from 1782 to 1786 and designed by the Bisontine architect Claude Joseph Alexandre Bertrand . The particularly high church tower is striking; it used to serve as a clock tower for the town hall opposite . The church of Saint-Maurice , founded in the 6th century, was rebuilt between 1711 and 1714 and given a Jesuit-style facade with a carillon on top. The Église Notre-Dame corresponds to the former Benedictine Abbey of Saint-Vincent , which was founded in the 11th century. It was made the parish church of Notre-Dame during the First Empire . Its facade was designed in 1720 by the architect Jean-Pierre Gazelot . However, its large entrance portal and the bell tower date from the 16th century. Today it is used by the humanities faculty. The Église Saint-François-Xavier was built as an old chapel of the Jesuit college between 1680 and 1688. It has a Latin cross plan , surrounded by small side chapels. In 1975 it was closed. The Saint-Paul Abbey was the church of the old abbey founded by Donatus in 628 . It was rebuilt in the 14th and 15th centuries and has a beautiful Gothic nave. The Notre-Dame-du-Foyer chapel , built by Nicolas Nicole from 1739 to 1745 , was formerly the chapel of the Couvent du Refuge until it was annexed in 1802 to the Saint-Jacques Hospital .

Outside the historic city center are two important Catholic churches. The Saint-Ferjeux basilica was built in Roman-Byzantine style on the cave of the patron saints Besançons, Ferreolus and Ferrutio . The Notre-Dame des Buis dates back to the 19th century and is 491 m above the city.

The old Hospice du Saint-Esprit, now the Temple du Saint-Esprit , was consecrated to the Protestant community in 1842 . It is a Gothic building from the 13th century, to which a chapel was added in the 15th century, but the church tower was destroyed during the French Revolution. His gallery with wood carvings by an unknown artist is important. Its neo-Gothic portal was built in 1841 by the architect Alphonse Delacroix in place of the old vestibule.

The Jewish community, which flourished in Besançon in the middle of the 19th century, had the synagogue built from 1869 to 1871 according to plans by Pierre Marnotte . The building was declared a Monument historique in 1984 and is notable for its Moorish style , inspired by the Alhambra in Granada . The youngest religious buildings in Besançon belong to the Islamic denomination. The Sunna Mosque was built in the Saint-Claude district on land made available by the city; the Al-Fath mosque is in the Planoise district .

Buildings

In Besançon there are 184 buildings classified as Monument historique (see also list of Monuments historiques in Besançon ). For its historical and cultural heritage and unique architecture, the city was awarded the City and Country of Art and History award by the French Ministry of Culture in 1986 .

The old town is surrounded by a loop of the Doubs and dominated by Besançon's landmark, the citadel (La Citadelle). In addition to a beautiful zoological garden with a noctarium , insectarium and an aquarium, the "Musée comptois" (objects on the traditions of Franche-Compté), the "Musée de la Résistance et de la Déportation" (Museum of Resistance and Deportation) and a small exhibition about the French builder Vauban . There is also a restaurant and souvenir shops there.

Many Hôtels particuliers from the 16th to 18th centuries (see Hôtel d'Anvers , Hôtel de Champagney , Petit Hôtel Chassignet , Hôtel Terrier de Santans and Hôtel Boistouset ) are classified as buildings worthy of protection.

theatre

- Opéra Théâtre

- Grand Kursaal

- Nouveau Théâtre - Center Dramatique National

- Théâtre Bacchus

- Théâtre de la Bouloie

- Théâtre de l'Espace

Festivals

- GéNéRiQ Festival (contemporary music) in February

- Festival International des Langues et des cultures du monde (theater) in March

- Festival de Besançon-Montfaucon (early music) in May

- Bien Urbain (street art) in June

- Festival jazz et musique improvisée en Franche-Comté festival (jazz and new improvisational music) in June

- Orgue en ville (organ concerts) in July

- Besançon - International Music Festival (classical music) in September

- Livres dans la Boucle (Book Fair) in September

- Festival Détonation (contemporary music) in September

- Lumières d'Afrique festival (African films) in November

movie theater

- Multiplex cinema Marché Beaux-Arts

- Multiplex cinema Mégarama

- Cinema Plazza Victor Hugo

- Kursaal

- Espace Planoise

Museums

Five museums in Besançon have been awarded the Musée de France award.

The Musée des beaux-arts et d'archéologie de Besançon is the oldest museum in France. It was founded in 1694, about 100 years before the Louvre . Today it is housed in an old grain market from 1835 and was refurbished in the 1960s by Louis Miquel , a student of Le Corbusier .

The Musée du Temps , which was inaugurated in 2002, was created on the basis of the city's history museum . It is located in the Palais Granvelle and combines in a unique concept its collection of wristwatches , sundials and hourglasses as well as other timepieces with the history museum's collection of paintings and engravings.

There are three museums in the citadel . The Musée de la Résistance et de la Déportation was opened in 1971 in the former cadet residence and is one of the most important of its kind in France. In 20 exhibition rooms, it deals with topics from the Second World War such as National Socialism , the occupation , the Vichy regime , deportation , Resistance and liberation and exhibits photographs, texts, documents and original objects. Two halls are dedicated to artists who created their works in concentration camps . The Musée Comtois , which was established in the Front Royal in 1961, is dedicated to the art and traditions of the region. A permanent exhibition of some of the museum's 20,000 objects from the 19th and 20th centuries is shown in 16 halls. The Muséum d'histoire naturelle, founded in 1959 on the initiative of the then mayor Jean Minjoz , offers a tour on the theme of evolution . Its zoo, insectarium , noctarium and aquarium exhibit live animals.

Parks and green spaces

With 2,408 hectares of green space , including 2,000 hectares of forest, Besançon is often referred to as the greenest city in France; per inhabitant it has 204 m² of green space. The Chailluz forest covers a quarter of the urban area with its 1625 hectares. The city owns this forest, which is largely made up of deciduous trees, and which has an animal park, an exercise trail, and several hiking trails.

The historic city center is surrounded by a green belt. To the west of the old town, on the left bank of the Doubs, are the gardens of the Gare d'eau . When the Rhine-Rhône Canal was built in 1833 , the city built a small port for canal shipping. When a canal was built below the citadel , this port became obsolete. The 2 hectare park around the former harbor basin belongs to the Conseil général du Doubs today .

Immediately to the north of these gardens is the Chamars promenade, which was laid out in the late 18th century and got its name from a contraction of the Champs de Mars (campus martii) . Originally there was swampy terrain at this location, which was divided into the small and large chamars by an arm of the Doubs. Vauban considered this place to be difficult to defend and therefore had it fortified with a wall and bastions. In 1739 the city was allowed to convert this place into a park. Under the direction of the Bisontine architect Claude-Joseph-Alexandre Bertrand , it was rebuilt from 1770 to 1778 and got a café, a public bath, an aviary for rare birds, cascades, a botanical garden and a park in the French style. In 1830 the inner wall was torn down to build the harbor; in the process, a large part of the former park facilities also disappeared. Between 1978 and 1982, the site was converted back into a park, with only two guard houses, a few plane trees and the stone vessels by the sculptor Jean-Baptiste Boutry remaining from the original complex .

To the north of the historic center of Battant, on the right bank of the Doubs, is the Promenade des Glacis, created in the mid-19th century and the work of the landscape architect Brice Michel and the architect Maurice Boutterin . In the center of Battant is the Clos Barbierier, laid out in 1988 , which houses a large number of roses. The botanical garden was founded in 1580. It then moved six times and has been at its current location in Place Leclerc since 1957 . The Jardins du Casino are a public park with flower meadows and tree-lined paths. In the Parc de l'observatoire, which was established in 1904 at the urging of the director of the astronomical observatory, Auguste Lebeuf, there are special copper beeches, hanging beeches, chestnuts and pines. In the Promenade Helvétie there is a botanical garden called Jardin des Sens et des Senteurs (Garden of Senses and Scents), which was created in 1987 and which introduces the visually impaired to plants and bushes with special smells or tangible features and which is equipped with explanatory panels in Braille .

The Micaud promenade was laid out step by step over 3 hectares on the right-hand side of the Doubs from 1843 according to plans by the architect Alphonse Delacroix . It bears the name of Jules Micaud , who, as the mayor at the time, commissioned the building. Among the 400 trees you will find special features such as large-flowered magnolias or beeches with deeply toothed leaves, a music hall, a water basin and numerous sculptures. The Granvelle Promenade was originally the private garden of the Granvelle Palace and dates back to the 16th century. The city bought it in 1712 and made it accessible to the public in 1728. Between 1775 and 1778 it was transformed into an ornamental garden by the architect Claude-Joseph-Alexandre Bertrand . Today there is a music hall, an artificial cave, a Wallace fountain , statues by Victor Hugo and Auguste Veil-Picard , the portal of the Église du couvent des Grands-Carmes church and a neoclassical portico that remains from a previous pavilion .

Besançon has numerous fountains, which is mainly due to the city's importance as a thermal bath.

Sports

- Soccer

- The city has the international soccer school on the premises

- Besançon Racing Club (BRC): Football

- Besançon Basket Comté Doubs (BBCD): basketball

- Entente Sportive Bisontine Féminin (ESBF): Handball (women)

- Entente Sportive Bisontine Masculine (ESBM): Handball (men)

Regular events

- February: Open de Franche-Comté, tennis tournament

- May: Foire Comtoise, exhibition, fair

- September: Les Mots Doubs, book fair

- September: Les Terroirs Gourmands, market for regional products

- December: Christmas market

Quotes

“When he had advanced one way in three days, he was informed that Ariovistus was hurrying with all his troops to occupy Vesentio, which is the largest city of the Sequani, and had advanced three days' march from his country. Caesar believed that he had to vigorously prevent this from happening. For of all things useful for the war there was the closest supply in this town, and its natural position made it so solid that it offered a good opportunity to prolong the war because of the Doubs, as if drawn around with a compass, surrounds most of the city; the remainder of the stretch where the river breaks - it is no more than 1,600 feet (480 m) - is taken by a mountain of great height, so that the base of the mountain touches the river banks on either side. A bypassed wall turns this (mountain) into a castle and connects it with the city. "

Personalities

- Claude Goudimel (around 1514–1572), musician (according to another source * 1500 in Vaison)

- Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle (1517–1586), cardinal, diplomat and humanist, adviser to Charles V, Viceroy of Naples

- Jean-Jacques Boissard (1528–1602), antique collector and Latin poet

- Jean-Baptiste Besard (1567–1617), lawyer, lutenist and composer

- Jean-Baptiste Chassignet (1571–1635), writer

- Jean Mairet (1604–1686), pre-classical playwright

- Claude-Adrien Nonnotte (1711–1793), Jesuit, preacher and writer

- Claude Étienne Le Bauld de Nans (1735–1792), actor, director and French teacher

- John Acton (1736–1811), Prime Minister of Naples under Ferdinand IV.

- Pierre-Adrien Pâris (1745–1819), painter and architect

- Antoine-François Momoro (1756–1794), printer

- Jean-François Flamand (1766–1838), infantry general

- Charles Fourier (1772–1837), inventor of the socialist "phalansteries"

- Charles Nodier (1780–1844), romantic writer

- Jean Claude Eugène Péclet (1793-1857), a physicist whose name by the Peclet number is known

- Victor Hugo (1802-1885), writer

- Jean-François Gigoux (1806–1894), painter and graphic artist

- Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809–1865), economist and sociologist, journalist (Le Peuple)

- Adolphe Braun (1812–1877), textile designer and photographer

- Paul Charreire (1820–1898), organist and composer

- Charles Lebouc (1822-1893), cellist

- Hilaire de Chardonnet (1839–1924), inventor of artificial silk

- Alfred Nicolas Rambaud (1842–1905), historian and politician

- Théobald Chartran (1849–1907), history and portrait painter

- Louis-Jean Résal (1854–1919), engineer (e.g. Pont Alexandre III in Paris )

- James Chappuis (1854–1934), natural scientist

- Georges Girardot (1856–1914), genre, nude and landscape painter

- Auguste Lumière (1862–1954) and Louis Lumière (1864–1948), inventors of cinematography and cinema

- Tristan Bernard (1866–1947), lawyer, journalist and humorist

- Max d'Ollone (1875–1959), composer

- Louis Koeltz (1884–1970), Lieutenant General, government representative of France on the Allied Control Council

- Émile Eigeldinger (1886–1973), racing cyclist

- André Bloch (1893–1948), mathematician

- Marcelle de Lacour (1896–1997), harpsichordist

- Henri Zeller (1896–1971), general and military governor of Paris

- Vital Dreyfus (1901–1942), doctor and resistance fighter

- Francis Borrey (1904–1976), doctor and politician

- Geneviève Carrez (1909–2014), German teacher and translator

- Janine Andrade (1918–1997), violinist

- Jean de Gribaldy (1922–1987), cyclist and sports director

- Fred Gérard (1924–2012), jazz trumpeter

- Robert Gigi (1926–2007), cartoonist

- Claude Lorius (* 1932), glaciologist

- Norbert Eschmann (1933–2009), Swiss football player

- Bernard Blum (1938–2014), agricultural scientist and industry manager

- Yves Jégo (* 1961), politician

- Maxence Cyrin (* 1971), pianist and composer

- Ursula Meier (* 1971), Swiss film director and actress

- Mina Agossi (* 1972), jazz singer and songwriter

- Julien Berthier (* 1975), visual artist

- Khedafi Djelkhir (* 1983), boxer

- Aurore Jéan (* 1985), cross-country skier

- Laura Glauser (* 1993), handball player

- Joseph Berlin-Sémon (* 1994), cyclist

- Axel Auriant (* 1998), actor

literature

- Martin Bauch, Ulrike Brummert (ed.): Besançon - A travel book . University Press of the Technical University of Chemnitz, Chemnitz 2012 ( digitized version ).

- Claude Fohlen (Ed.): Histoire de Besançon. Des origines à la fin du XVIe siècle . (Part 1). Besançon 1981, ISBN 2-901040-27-6 .

- Claude Fohlen (Ed.): Histoire de Besançon. De la Conquête française à nos jours . (Volume 2). Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 .

- Reinhold Kaiser: Besançon . In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages (LexMA). Volume 1, Artemis & Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1980, ISBN 3-7608-8901-8 , Sp. 2052-2055.

Web links

swell

- ↑ Jean-Louis Fousseret : Mission d'information commune sur les perspectives économiques et sociales de l'aménagement de l'axe européen Rhin-Rhône, in: Rapport d'information N ° 1920 de l'Assemblée Nationale of November 15, 1999. Visited on December 17, 2012.

- ^ French Ministry of the Environment, Direction régionale de l'Industrie, de la Recherche et de l'Environnement, Bureau de Recherches Géologiques et Minières: Le schéma départemental des carrières du Doubs, June 16, 1998. Visited on November 17, 2012.

- ↑ Vincent Bichet and Michel Campy: Montagnes du Jura, Géologie et Paysages. Besançon 2008, ISBN 978-2-914741-61-3 .

- ↑ Ville de Besançon - L'observatoire socio-urbain ( Memento of December 8, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 4.9 MB).

- ^ Fiche technique , Ville de Besançon ( Memento of November 17, 2008 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ Records météorologiques pour la station de Besançon. In: lameteo.org. Retrieved December 3, 2015 (French).

- ^ Météo France online, visited on November 20, 2009.

- ↑ Claude Fohlen (Ed.): Histoire de Besançon: Des origines à la fin du XVIe siècle, Volume 1, Besançon 1981, ISBN 2-901040-27-6 , pp. 29-34.

- ↑ Claire Stoullig (ed.): De Vesontio à Besançon, Neuchatel (Chaman Édition) of 2006.

- ^ Julius Caesar, De bello gallico, Book I, Section 38.

- ↑ Jean Leclant and Christian Goudineau: Dictionnaire de l'Antiquité, éd. Pouf.

- ↑ Académie de Besançon: Besançon gallo-romain, ( Memento of December 8, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) visited on March 30, 2010.

- ^ Institut National de Recherches Archéologiques Préventives: Communiqué de presse ( Memento of December 8, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) of April 15, 2004.

- ↑ Claude Fohlen (Ed.): Histoire de Besançon: Des origines à la fin du XVIe siècle, Volume 1, Besançon 1981, ISBN 2-901040-27-6 , pp. 214-219.

- ^ Claude Fohlen (ed.): Histoire de Besançon: Des origines à la fin du XVIe siècle, Volume 1, Besançon 1981, ISBN 2-901040-27-6 , pp. 229-231.

- ↑ Lettres patentes de Louis XI, Thouars, février 1481 (1480 avant Pâques), available online.

- ↑ Lettres patentes de Louis XI, Plessis-du-Parc-lèz-Tours, mars 1481 (1480 avant Pâques), available online.

- ↑ Lettres patentes de Louis XI, Plessis-du-Parc-lèz-Tours, mars 1481 (1480 avant Pâques), available online. After the king's death in 1483, this relocation was not carried out.

- ↑ Claude Fohlen (ed.): Histoire de Besançon: Des origines à la fin du XVIe siècle, Volume 1, Besançon 1981, ISBN 2-901040-27-6 , p. 583.

- ^ Claude Fohlen (Ed.): Histoire de Besançon: Des origines à la fin du XVIe siècle, Volume 1, Besançon 1981, ISBN 2-901040-27-6 , pp. 603-604.

- ↑ Claude Fohlen (ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , p. 9.

- ↑ Claude Fohlen (Ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , pp. 20-21.

- ↑ Claude Fohlen (ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , p. 25.

- ^ Claude Fohlen (Ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , pp. 26-29.

- ↑ Claude Fohlen (Ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , pp. 35-37.

- ^ Claude Fohlen (ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , p. 38.

- ↑ Claude Fohlen (ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , p. 41.

- ↑ Bernard Pujo: Vauban, Albin Michel 1991, ISBN 2-226-05250-X , p. 75.

- ↑ Claude Fohlen (Ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , p. 42.

- ^ Claude Fohlen (Ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , p. 46.

- ↑ Claude Fohlen (Ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , pp. 55-68.

- ↑ Claude Fohlen (Ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , p. 238.

- ↑ Claude Fohlen (Ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , p. 233.

- ^ Claude Fohlen (Ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , pp. 251-253.

- ↑ Claude Fohlen (Ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , p. 378.

- ^ Claude Fohlen (ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , p. 379.

- ↑ Claude Fohlen (Ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , p. 380.

- ↑ Claude Fohlen (Ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , pp. 380-382.

- ↑ Claude Fohlen (ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , pp. 487-488.

- ↑ Claude Fohlen (ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , p. 489.

- ↑ Claude Fohlen (Ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , p. 493.

- ↑ Claude Fohlen (Ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , p. 500.

- ^ Claude Fohlen (Ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , pp. 501-502.

- ↑ Stéphane Simonnet: Atlas de la Liberation de la France. Paris 1994, ISBN 2-7467-0495-1 , p. 35.

- ^ Claude Fohlen (ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , p. 505.

- ↑ Claude Fohlen (ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , p. 508.

- ^ Claude Fohlen (Ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , p. 513.

- ↑ Claude Fohlen (Ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , p. 517.

- ↑ Claude Fohlen (Ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , p. 518.

- ^ Claude Fohlen (ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , p. 519.

- ↑ Claude Fohlen (Ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , p. 521.

- ↑ Claude Fohlen (Ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , p. 523.

- ^ Claude Fohlen (Ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , p. 530.

- ^ Claude Fohlen (ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , p. 531.

- ^ Claude Fohlen (ed.): Histoire de Besançon: De la Conquête française à nos jours, Volume 2, Besançon 1982, ISBN 2-901040-21-7 , pp. 570-571.

- ↑ Hebdo de Besançon: Les Prés-de-Vaux, cœur de l'activité ouvrière bisontine, May 30, 2007.

- ↑ Insee: Population de l'aire urbaine de Besançon, ( Memento of November 5, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) visited on November 13, 2010.

- ↑ Base de données Cassini: Demographie de la commune de Besançon, visited on September 6, 2013.

- ^ INSEE: Chiffres Clé, visited on September 6, 2013.

- ^ Réseau Ferré de France (RFF): LGV Rhin-Rhône - Branche Est, visited on October 27, 2012.

- ↑ Rivernet.org: Abandon du projet canal Rhin Rhône, visited on October 27, 2012.

- ↑ Philippe DEFAWE: La relance du canal Rhin-Rhône parmi les Priorites du gouvernement, in: Le Moniteur des Travaux Publics et du bâtiment , April 7, 2006 ( ISSN 0026-9700 ), visited on 27 October 2012 found.

- ↑ Le tramway du Grand Besançon: Les étapes du projet, ( Memento from 23 September 2016 in the Internet Archive ) visited on 18 June 2014.

- ↑ Ville de Besançon: AutoCité - voitures en libre service, visited on October 27, 2012.

- ↑ Hermann Wille: Great moments of technology. Leipzig 1987.

- ↑ Eglise catholique de Besançon: Qui sont les saints patrons de notre unité pastorale? ( Memento of July 4, 2009 in the Internet Archive ), visited on October 28, 2012.

- ↑ a b Claude Fohlen (ed.): Histoire de Besançon: Des origines à la fin du XVIe siècle, Volume 1, Besançon 1981 ISBN 2-901040-27-6 , pp. 161–167.

- ↑ Yves Jeannin: Le peuple christianisé à la recherche de “ses martyrs”: le cas de Besançon, Mélanges Pierre Lévêque, Besançon 1992, pp. 127-138.

- ↑ Besançon autrefois, pp. 64–72.

- ↑ BVV: Le député de Besançon et l'armée indigène en 1915 (PDF; 6.1 MB), November 2006.

- ↑ a b c migrations.besancon.fr: Islam et Bouddhisme à Besançon, visited on October 28, 2012.

- ↑ La Passerelle: Inauguration de la mosquée de Planoise, visited on October 28, 2012.

- ^ Tribune juive , number 91, p. 22.

- ↑ Ville de Besançon: Laissez-vous conter la Porte Noire (PDF; 1.5 MB), visited on October 21, 2012.

- ↑ Eveline Toillon: Besancon: Insolite et secret. Saint-Cyr-sur-Loire 2003, ISBN 2-84253-914-1 , p. 35.

- ↑ Eveline Toillon: Besancon: Insolite et secret, Saint-Cyr-sur-Loire in 2003, ISBN 2-84253-914-1 , S. 106th

- ↑ Eveline Toillon: Besancon: Insolite et secret. Saint-Cyr-sur-Loire 2003, ISBN 2-84253-914-1 , pp. 101-102.

- ↑ Eveline Toillon: Besancon: Insolite et secret. Saint-Cyr-sur-Loire 2003, ISBN 2-84253-914-1 , p. 113.

- ↑ Dominique Bonnet and Denis Maraux: Découvrir Besançon, Châtillon-sur-Chalaronne (La Taillanderie) 2002, ISBN 2-87629-257-2 , p. 21.

- ↑ Dominique Bonnet and Denis Maraux: Découvrir Besançon, Châtillon-sur-Chalaronne (La Taillanderie) 2002, ISBN 2-87629-257-2 , pp. 38-39.

- ↑ Shadowspro.com: Cadrans Solaires de Besançon, visited on October 28, 2012.

- ↑ Antoine Reverchon: Les grandes villes passées au crible (PDF; 1.2 MB), in: Le Monde (supplément développement durable) of November 10, 2004, p. II ( ISSN 0395-2037 ).

- ↑ Dominique Bonnet and Denis Maraux: Découvrir Besançon, Châtillon-sur-Chalaronne (La Taillanderie) 2002, ISBN 2-87629-257-2 , p. 44.

← Previous location: Cussey-sur-l'Ognon 17.0 km | Besançon | Next town: Étalans 27.0 km →

![]() Canterbury |

Dover |

Calais |

Wissant |

Guînes |

Licques |

Wisques |

Thérouanne |

Auchy-au-Bois |

Bruay-la-Buissière |

Arras |

Bapaume |

Peronne |

Doingt |

Seraucourt-le-Grand |

Tergnier |

Laon |

Bouconville-Vauclair |

Corbeny |

Hermonville |

Reims |

Trépail |

Châlons-en-Champagne |

Cool |

Brienne-le-Château |

Bar-sur-Aube |

Châteauvillain |

Blessonville |

Langres |

Humes-Jorquenay |

Coublanc |

Grenant |

Dampierre-sur-Salon |

Savoyeux |

Seveux |

Gy |

Cussey-sur-l'Ognon |

Besançon |

Étalans |

Chasnans |

Nods |

Ouhans |

Pontarlier |

Yverdon-les-Bains |

Orbe |

Lausanne |

Cully |

Vevey |

Montreux |

Villeneuve |

Aigle |

Saint-Maurice |

Martigny |

Orsières |

Bourg-Saint-Pierre |

Great St. Bernhard |

Saint-Rhémy-en-Bosses |

Saint-Oyen |

Étroubles |

Gignod |

Aosta |

Saint-Christophe |

Quart |

Nut |

Verrayes |

Chambave |

Saint-Denis |

Châtillon |

Saint-Vincent |

Montjovet |

Issogne |

Verrès |

Arnad |

Hône |

Bard |

Donnas |

Pont-Saint-Martin |

Carema |

Settimo Vittone |

Borgofranco d'Ivrea |

Montalto Dora |

Ivrea |

Cascinette d'Ivrea |

Burolo |

Bollengo |

Palazzo Canavese |

Piverone |

Azeglio |

Viverone |

Roppolo |

Cavaglià |

Santhià |

San Germano Vercellese |

Olcenengo |

Salasco |

Sali Vercellese |

Vercelli |

Palestro |

Robbio |

Nicorvo |

Castelnovetto |

Albonese |

Mortara |

Cergnago |

Tromello |

Garlasco |

Gropello Cairoli |

Villanova d'Ardenghi |

Zerbolò |

Carbonara al Ticino |

Pavia |

Valle Salimbene |

Linarolo |

Belgioioso |

Torre de 'Negri |

Costa de 'Nobili |

Santa Cristina e Bissone |

Miradolo Terme |

Chignolo Po |

San Colombano al Lambro |

Orio Litta |

Senna Lodigiana |

Calendasco |

Rottofreno |

Piacenza |

Podenzano |

San Giorgio Piacentino |

Pontenure |

Carpaneto Piacentino |

Cadeo |

Fiorenzuola d'Arda |

Chiaravalle della Colomba |

Alseno |

Busseto |

Fidenza |

Costamezzana |

Noceto |

Medesano |

Fornovo di Taro |

Terenzo |

Berceto |

Pontremoli |

Filattiera |

Villafranca in Lunigiana |

Bagnone |

Licciana Nardi |

Aulla |

Santo Stefano di Magra |

Sarzana |

Castelnuovo Magra |

Ortonovo |

Luni |

Fosdinovo |

Carrara |

Massa |

Montignoso |

Seravezza |

Pietrasanta |

Camaiore |

Lucca |

Capannori |

Porcari |

Montecarlo |

Altopascio |

Castelfranco di Sotto |

Santa Croce sull'Arno |

Ponte a Cappiano |

Fucecchio |

San Miniato |

Castelfiorentino |

Coiano |

Montaione |

Gambassi Terme |

San Gimignano |

Colle di Val d'Elsa |

Badia a Isola |

Monteriggioni |

Siena |

Monteroni d'Arbia |

Ponte d'Arbia |

Buonconvento |

Montalcino |

Torrenieri |

San Quirico d'Orcia |

Bagno Vignoni |

Castiglione d'Orcia |

Radicofani |

San Casciano dei Bagni |

Abbadia San Salvatore |

Piancastagnaio |

Ponte a Rigo |

Proceno |

Acquapendente |

Grotte di Castro |

San Lorenzo Nuovo |

Bolsena |

Montefiascone |

Viterbo |

Ronciglione |

Vetralla |

Capranica |

Sutri |

Monterosi |

Nepi |

Mazzano Romano |

Campagnano di Roma |

Formello |

La Storta |

Rome

Canterbury |

Dover |

Calais |

Wissant |

Guînes |

Licques |

Wisques |

Thérouanne |

Auchy-au-Bois |

Bruay-la-Buissière |

Arras |

Bapaume |

Peronne |

Doingt |

Seraucourt-le-Grand |

Tergnier |

Laon |

Bouconville-Vauclair |

Corbeny |

Hermonville |

Reims |

Trépail |

Châlons-en-Champagne |

Cool |

Brienne-le-Château |

Bar-sur-Aube |

Châteauvillain |

Blessonville |

Langres |

Humes-Jorquenay |

Coublanc |

Grenant |

Dampierre-sur-Salon |

Savoyeux |

Seveux |

Gy |

Cussey-sur-l'Ognon |

Besançon |

Étalans |

Chasnans |

Nods |

Ouhans |

Pontarlier |

Yverdon-les-Bains |

Orbe |

Lausanne |

Cully |

Vevey |

Montreux |

Villeneuve |

Aigle |

Saint-Maurice |

Martigny |

Orsières |

Bourg-Saint-Pierre |

Great St. Bernhard |

Saint-Rhémy-en-Bosses |

Saint-Oyen |

Étroubles |

Gignod |

Aosta |

Saint-Christophe |

Quart |

Nut |

Verrayes |

Chambave |

Saint-Denis |

Châtillon |

Saint-Vincent |

Montjovet |

Issogne |

Verrès |

Arnad |

Hône |

Bard |

Donnas |

Pont-Saint-Martin |

Carema |

Settimo Vittone |

Borgofranco d'Ivrea |

Montalto Dora |

Ivrea |

Cascinette d'Ivrea |

Burolo |

Bollengo |

Palazzo Canavese |

Piverone |

Azeglio |

Viverone |

Roppolo |

Cavaglià |

Santhià |

San Germano Vercellese |

Olcenengo |

Salasco |

Sali Vercellese |

Vercelli |

Palestro |

Robbio |

Nicorvo |

Castelnovetto |

Albonese |

Mortara |

Cergnago |

Tromello |

Garlasco |

Gropello Cairoli |

Villanova d'Ardenghi |

Zerbolò |

Carbonara al Ticino |

Pavia |

Valle Salimbene |

Linarolo |

Belgioioso |

Torre de 'Negri |

Costa de 'Nobili |

Santa Cristina e Bissone |

Miradolo Terme |

Chignolo Po |

San Colombano al Lambro |

Orio Litta |

Senna Lodigiana |

Calendasco |

Rottofreno |

Piacenza |

Podenzano |

San Giorgio Piacentino |

Pontenure |

Carpaneto Piacentino |

Cadeo |

Fiorenzuola d'Arda |

Chiaravalle della Colomba |

Alseno |

Busseto |

Fidenza |

Costamezzana |

Noceto |

Medesano |

Fornovo di Taro |

Terenzo |

Berceto |

Pontremoli |

Filattiera |

Villafranca in Lunigiana |

Bagnone |

Licciana Nardi |

Aulla |

Santo Stefano di Magra |

Sarzana |

Castelnuovo Magra |

Ortonovo |

Luni |

Fosdinovo |

Carrara |

Massa |

Montignoso |

Seravezza |

Pietrasanta |

Camaiore |

Lucca |

Capannori |

Porcari |

Montecarlo |

Altopascio |

Castelfranco di Sotto |

Santa Croce sull'Arno |

Ponte a Cappiano |

Fucecchio |

San Miniato |

Castelfiorentino |

Coiano |

Montaione |

Gambassi Terme |

San Gimignano |

Colle di Val d'Elsa |

Badia a Isola |

Monteriggioni |

Siena |

Monteroni d'Arbia |

Ponte d'Arbia |

Buonconvento |

Montalcino |

Torrenieri |

San Quirico d'Orcia |

Bagno Vignoni |

Castiglione d'Orcia |

Radicofani |

San Casciano dei Bagni |

Abbadia San Salvatore |

Piancastagnaio |

Ponte a Rigo |

Proceno |

Acquapendente |

Grotte di Castro |

San Lorenzo Nuovo |

Bolsena |

Montefiascone |

Viterbo |

Ronciglione |

Vetralla |

Capranica |

Sutri |

Monterosi |

Nepi |

Mazzano Romano |

Campagnano di Roma |

Formello |

La Storta |

Rome![]()

![]()

![]()