Mathilde of Canossa

Mathilde (also Mathilde von Tuszien ; * around 1046; † July 24, 1115 in Bondeno ) from the family of the Lords of Canossa was one of the most powerful nobles in Italy in the second half of the 11th century.

As margravine she ruled over large areas of Tuscany and Lombardy . As a relative of the Salian imperial family, she brokered a settlement in the so-called investiture dispute . In this extensive conflict with the emerging reform papacy over the relationship between spiritual ( sacerdotium ) and secular ( regnum ) power, Pope Gregory VII dismissed and excommunicated the Roman-German King Henry IV in 1076 . In January 1077, after his penance in front of Canossa Castle ( Canusia in Latin ), Gregory was re-accepted into the community of the sacrament by Gregory . The understanding between the king and the pope was short-lived. In the conflicts with Henry IV that arose a little later, Mathilde put all her military and material potential into the service of the reform papacy from 1080. During the turmoil of the investiture dispute, their farm became a place of refuge for numerous displaced persons and experienced a cultural boom. Even after Gregory's death in 1085, Mathilde remained an important pillar of the Reform Church. Between 1081 and 1098 the Canusinian rule got into a great crisis due to the grueling disputes with Henry IV. The documentary and letter transmission is largely suspended for this time. A turning point resulted from a coalition of the Canusine woman with the southern German dukes, who were in opposition to Heinrich.

After Heinrich's retreat in 1097 to the empire north of the Alps, a power vacuum developed in Italy. The struggle between regnum and sacerdotium changed the social and rulership structure of the Italian cities permanently and gave them space for emancipation from foreign rule and communal development. From autumn 1098 Mathilde was able to regain many of the lost areas. Until the end she tried to bring the cities under her control. After 1098, she increasingly used the opportunities offered by the use of script to consolidate her rule again. In her last years she was worried about her own memory , which is why the childless Mathilde concentrated her donation activities solely on the Polirone monastery as her heir.

With Mathilde's death, the family died out in 1115. Popes and emperors fought over their rich inheritance, the " Mathildic goods ", well into the 13th century. Mathilde became a myth in Italy, which found its expression in numerous artistic, musical and literary designs as well as miracle stories and legends. The aftermath reached its peak during the Counter-Reformation and the Baroque . Pope Urban VIII had Mathilde's body transferred to Rome in 1630, where she was the first woman to be buried in Saint Peter . Posterity will especially remember her role in the meeting between Pope Gregory VII and King Henry IV in the late January days of 1077.

Life until the assumption of power

Origin and rise of the Canusiner

Mathilde came from the noble family of Canossa, the Canusiner , a name that was only invented by later generations. The oldest proven ancestor of the Canusines is Siegfried (Sigefredus), who lived in the first third of the 10th century and came from the county of Lucca . He probably increased his sphere of influence in the area around Parma and probably also in the foothills of the Apennines . His son Adalbert-Atto was able to bring several castles in the foothills of the Apennines under his control in the politically fragmented region. He built in the mountains southwest of Reggio and the castle of Canossa to a fortress.

In the year 950 King Lothar of Italy died suddenly , whereupon Berengar von Ivrea wanted to take power in Italy. After a short imprisonment, Lothar's widow Adelheid found refuge with Adalbert-Atto in Canossa Castle. The East Frankish-German King Otto I then intervened in Italy himself and married Adelheid in 951. This resulted in a close bond between the Canusines and the Ottonian ruling family. Adalbert-Atto appeared in the king's documents as an advocate and was able to establish contacts with the papacy for the first time in the wake of the Ottonian. The ruler also owed Adalbert-Atto the award of the counties of Reggio and Modena . In 977 at the latest, the dignity of Mantua was added.

Adalbert's son and Mathilde's grandfather Tedald continued their close ties to the Ottonian rulers from 988. In 996 he is listed as dux et marchio (Duke and Margrave) in a document. This title was adopted by all subsequent Canusins.

A division of the inheritance among the three sons of Tedald could be prevented. The rise of the family reached a climax under Mathilde's father Boniface von Canossa . The Canusiner Atto, Tedald and Bonifaz instrumentalized monasteries for their expansive expansion of rule. They founded monasteries ( Brescello , Polirone , Santa Maria di Felonica ) in places that were important in terms of transport policy and strategy for the administrative consolidation of larger property masses, used three family saints (Genesius, Apollonius and Simeon) to stabilize the Canusinian power structure and strove to exert influence on long-standing convents ( Nonantola Abbey ). The transfer of monasteries to local bishops and the promotion of spiritual institutions also enlarged their network. The appearance as the guardian of order consolidated their position along the Via Emilia . Arnaldo Tincani was able to prove the considerable number of 120 farms in the Canossa estate in the Po area .

Boniface worked closely with the Salian ruler Konrad II . He received the Margraviate of Tuscany in 1027, thereby doubling the Canusiner's domain. Boniface rose to become the most powerful person between the middle Po and the northern border of the Patrimonium Petri . Emperor Konrad wanted to tie his most important partisan south of the Alps to himself in the long term through a marriage. On the occasion of the wedding of Konrad's son Heinrich III. Bonifaz probably met Beatrix with Gunhild in Nijmegen . She was most likely married in 1037 to the much older Margrave Boniface of Tuszien-Canossa. In the marriage, Beatrix brought important marriage assets in Lorraine. As the daughter of Duke Friedrich of Upper Lorraine , she was brought up in the vicinity of Empress Gisela after his death . For Boniface, marriage to a duke's daughter and relatives of the emperor brought prestige and the prospect of an heir.

The Canusinians were not a noble family with many children. The relationship with Beatrix resulted in a son and two daughters. Friedrich and little Beatrix died in 1055 at the latest. Mathilde, who was probably born in 1046, survived as the youngest daughter. Boniface was a feared prince throughout his life and, for some small vassals , a hated prince. He was murdered in May 1052 while hunting in a forest near Mantua . In the years that followed, his widow was largely able to keep the family estates together. She also made important contacts with leading figures in the church renewal movement and developed into an increasingly important pillar of the reform papacy.

Mathilde's birthplace and birthday are unknown. Italian scholars have been arguing about her place of birth for centuries. She was born in Lucca after Francesco Maria Fiorentini , a Lucca doctor and scholar of the 17th century . For the Reggian Benedictine Camillo Affarosi , Canossa was their place of birth. Lino Lionello Ghirardini and Paolo Golinelli advocated Mantua. A recent publication by Michèle K. Spike also favors Mantua as it was the center for Boniface's court at the time. In addition, were Ferrara or the small Tuscan town of San Miniato discussed. According to Elke Goez, there is no evidence of a permanent court in the sources for Mantua or any other place.

Mathilde must have spent the early years around her mother. With the death of her brother Friedrich, the family's position became much more difficult. Beatrix hoped to maintain Boniface's legacy by remarrying. Probably in the summer or autumn of 1054 she married Heinrich III. Deposed Duke Gottfried the Bearded of Lower Lorraine. But with that she had a marital connection with one of Henry III's worst enemies. closed. Heinrich moved to Italy in 1055, but Gottfried was able to flee. It is no longer in the tradition for more than a year. Beatrix and her daughter Mathilde submitted to the emperor in Florence . Mother and daughter were taken as prisoners to the empire north of the Alps. Their exact whereabouts remain unknown. Heinrich did not give the imperial fiefs of the late Boniface to third parties, but kept these goods.

Due to the early death of the emperor at the age of 39 in October 1056, the family was able to return to Italy a few months later and began to restore the previous balance of power. She was supported by the papacy. Pope Viktor II had accompanied the Canusines on their return. In June 1057 he held a synod in Florence. Viktor was not only present at the humiliation of Beatrix in Florence, but the programmatic choice of location of the Synod also made it clear that the Canusinians had returned to Italy strengthened at the side of the Pope and had been completely rehabilitated. While Henry IV was a minor, the reform papacy sought protection from the Canusins. According to Donizo, the panegyric biographer Mathilde and her ancestors, Mathilde was fluent in both French and German due to her origins and living conditions.

Marriage to Gottfried the Hunchback

Possibly using the time Henry IV was a minor, Beatrix and Gottfried wanted to consolidate the connection between Lorraine and Canossa in the long term by marrying their two children. In 1069 Mathilde married Gottfried the Hunchback . The couple stayed in Lorraine, Beatrix returned to Italy alone. Mathilde became pregnant in 1070. Gottfried seems to have informed the Salian royal court about this event. In a document from Henry IV dated May 9, 1071, Duke Gottfried or his heirs are mentioned. Mathilde gave her daughter the name of her mother, but the child died a few weeks after the birth on January 29, 1071.

Mathilde's marriage to Gottfried failed after a short time. She fled to her mother in Italy, where her stay in Mantua on January 19, 1072 can be proven. There she and her mother issued a deed of donation for the St. Andrew's monastery . However, Gottfried did not want to accept the separation from his wife. As early as 1072 he moved across the Alps and visited several places in Tuscany; apparently, as Mathilde's husband, he laid claim to these areas. Mathilde stayed in Lucca during this time. There is no evidence that the couple met. Only in a single document dated August 18, 1073 in Mantua for the monastery of San Paolo in Parma , Mathilde named Gottfried as her husband. In the summer of 1073 Gottfried had left Italy and returned to Lorraine. Mathilde wanted to continue her life in a monastery. In 1073/74 she tried in vain to dissolve the marriage relationship with the Pope. The Pope needed Duke Gottfried as an ally and was therefore not interested in a divorce. At the same time he hoped for Mathilde's help with his crusade plans. As a result, the couple continued to live separately until Gottfried was assassinated in February 1076. Mathilde made no spiritual gifts either for Gottfried or for her child, who died young. Her mother Beatrix, however, had founded the Frassinoro Abbey in 1071 for the salvation of her granddaughter Beatrix and donated twelve farms "for the health and life of my beloved daughter Mathilde" ("pro incolomitate et anima Matilde dilecte filie mee").

Introduction to the rulership by her mother Beatrix

After her unsuccessful marriage, Mathilde wanted to become a nun, but her mother began to build her up as a presumptive successor in the entire Canusin region and sought the broadest possible public consensus. Shortly after her return, Mathilde and her mother made a deed in Mantua on January 19, 1072. They donated their court in Fornigada to the St. Andrew's monastery there. The two princesses tried to be present throughout their territory. In today's Emilia-Romagna region , their position was much more stable than in the southern Apennines, where they could not get their followers behind them despite rich donations. They therefore tried to act as guardians of justice and public order. Mathilde's participation is mentioned in seven of the sixteen placita held by Beatrix . Supported by judges, Mathilde has already held three placita alone. On June 7, 1072 Mathilde and her mother presided over the court in favor of the monastery of San Salvatore on Monte Amiata . On February 8, 1073 Mathilde presided over the court in Lucca in favor of the local monastery of San Salvatore e Santa Giustina without her mother . At the instigation of the abbess Eritha, the monastery properties in Lucca and Villanova am Serchio were secured by the royal spell . Mathilde's stay is unknown for the next six months, while her mother attended the enthronement ceremonies for Pope Gregory VII.

Her mother introduced Mathilde to numerous personalities in church reform, especially Pope Gregory VII himself. Mathilde had already met the future Pope, then Archdeacon Hildebrand, in the 1960s . After his election as Pope, she met him for the first time from March 9th to 17th, 1074. With Mathilde and Beatrix, the Pope developed a special relationship of trust in the period that followed. However, Beatrix died on April 18, 1076. On August 27, 1077 Mathilde donated her court Scanello and other real estate to the extent of 600 manses near the court to Bishop Landulf and the cathedral chapter of Pisa as a soul device for herself and her parents .

Rule of the Margravine Mathilde

Mathilde's role during the investiture controversy

State of the empire when Mathilde came to power

After the death of her mother, Mathilde took over the inheritance, contrary to the provisions of the Salian and Lombard law in force in Italy , according to which Henry IV would have been the legal heir. A fief under imperial law was of subordinate importance for the Canusinians in view of the minority of Henry IV and the close cooperation with the reform papacy.

Mathilde's mother died at the time when the conflict between Henry IV and Pope Gregory VII was escalating. Mathilde and Beatrix were among Gregory's closest confidants. From the beginning he took her into his confidence and let her know about his plans against the Roman-German king. On a court day in Worms on January 24, 1076, the king, together with the two archbishops Siegfried von Mainz and Udo von Trier, as well as another 24 bishops, formulated drastic accusations against Gregory VII. They dismissed him from obedience. The allegations concerned Gregor's election, which was described as illegitimate, the government of the Church through a “women’s senate” and that “he shared a table with a strange woman and housed her, more familiar than necessary”. The contempt was so immense that Mathilde was not even called by name. The Pope reacted on February 15, 1076 with the excommunication of the king and released his followers from the oath of loyalty by virtue of his power of binding and redemption. These measures had a tremendous effect on contemporaries, as the words of the Gregorian Bonizo von Sutri show: "When the news of the banishment of the king reached the ears of the people, our whole world trembled."

Efforts to find a balance between King and Pope

Mathilde was a second cousin of Henry IV through the Empress Gisela. Because of her family ties to the Salians, she was suitable for a mediator role between royalty and the Roman Church. The princes asked Heinrich to break away from the ban within a year. Heinrich then crossed the Alps in winter and appeared in front of Canossa Castle on January 25, 1077. He moved into the Bianello castle . Since Mathilde's castles became the setting for the reconciliation between the emperor and the Pope, she must have been very closely involved in the negotiations. According to the agreement reached through intermediaries, the king spent three days in the forecourt of Canossa Castle in a penitent's robe, barefoot and without a sign of authority, despite the winter cold. Thereupon Gregor released him from the spell and took him back into the church. For Mathilde, the days in Canossa were a challenge. All those arriving had to be accommodated and looked after appropriately. She had to take care of the procurement and storage of food and fodder, and the supplies in the middle of winter. After the ban was dissolved, Heinrich stayed in the Po Valley for several months and demonstratively devoted himself to his rulership. Pope Gregory stayed in Mathilde's castles for the next few months. Heinrich and Mathilde never met again in person after the Canossa days. In the years from 1077 to 1080 Mathilde went about the usual activities of her rule. In addition to a few donations for the diocese of Lucca and Mantua, court documents dominate.

Disputes with Henry IV.

At the Roman synod of Lent in early March 1080 Heinrich was again banned by Gregory. The Pope combined this with a prophecy: If the Salier does not go under by August 1st, he should be chased out of office, Gregory. But unlike the first ban, the bishops and princes stood behind Heinrich. In Brixen on June 25th of the same year, seven German, one Burgundian and 20 Italian bishops decided to depose Gregory VII and nominated Archbishop Wibert of Ravenna as Pope. The break between the king and the pope also escalated the relationship between Heinrich and Mathilde. In September 1080 Mathilde sat in court on behalf of the Bishop of Ferrara . There the Margraves Azzo von Este, the Counts Ugo and Ubert, Albert, the son of Count Boso, Paganus von Corsina, Fulcus von Rovereto, Gerhard von Corviago, Petrus de Ermengarda and Ugo Armatus met. Mathilde swore her faithful to the upcoming fight against Heinrich. In October 1080 an army of the margravine suffered a defeat at Volta Mantovana against troops close to the king . Some Tuscan count houses took advantage of the uncertainty and positioned themselves against Mathilde. Few places remained true to her. In a donation of December 9, 1080 to the monastery of San Prospero , only a few local followers are named.

Heinrich crossed the Alps in the spring of 1081. He gave up his previous reluctance towards his cousin Mathilde and honored the city of Lucca for their transfer to the royal side. On June 23, 1081, Heinrich issued the citizens of Lucca a comprehensive privilege in the army camp outside Rome. By granting special urban rights, the king intended to weaken the rule of the Marquis of Canossa. In July 1081 a committee which meets under chairmanship of Henry Hofgericht in Lucca imposed on Mathilde even the imperial ban . All goods and fiefs were withdrawn from her. The consequences for Mathilde were relatively minor in Italy, but she suffered losses in her far-away Lorraine possessions. On June 1, 1085, Heinrich gave Mathilde's goods Stenay and Mosay to Bishop Dietrich von Verdun .

A guerrilla war developed which Mathilde waged from her castles in the Apennines. In 1082 she was apparently insolvent. Therefore she could no longer bind her vassals to her with generous gifts or fiefs. But even in dire straits she did not let up in her zeal for the reform papacy. Although her mother was also a supporter of church reform, she had distanced herself from Gregor's revolutionary goals, where these endangered the foundations of her rule structures. In this attitude, mother and daughter are clearly different from each other. Mathilde had the church treasure of the Apollonius monastery built near Canossa Castle melt down. Precious metal vessels and other treasures from Nonantola Abbey were also melted down. Mathilde sold her Allod Donceel to the Abbey of Saint-Jacques in Liège. She made the proceeds available to Pope Gregory. The royal side then accused her of plundering churches and monasteries. Pisa and Lucca sided with Henry. As a result, Mathilde lost two of her most important pillars of power in Tuscany. She had to stand by and watch as anti-Gregorian bishops were installed in several places.

In the summer of 1084 an outnumbered army of the margravine achieved a success against Heinrich's troops at Sorbara, northeast of Modena. Mathilde was able to take the Cologne-born Bishop Eberhard von Parma hostage. In 1085, together with Thedald , the Archbishop of Milan , and the Bishops Gandulf of Reggio Emilia and Eberhard of Parma , clergy who were critical of the reform papacy died. Mathilde took this opportunity and filled the bishops' see in Modena, Reggio and Pistoia with Gregorians again.

On his third march to Italy, Heinrich besieged Mantua and thus attacked the sphere of influence of Margravine Mathilde. In April 1091 he was able to take the city after an eleven month siege. In the following months Heinrich achieved further successes against the vassals of the margravine. In the summer of 1091 he managed to get the entire area north of the Po with the counties of Mantua, Brescia and Verona under his control. In 1092 Heinrich was able to conquer most of the counties of Modena and Reggio. In the course of the military conflict, the monastery of San Benedetto Po suffered severe damage, so that on October 5, 1092, Mathilde donated the church of San Prospero, the church of San Donino in Monte Uille and the church of San Gregorio in Antognano to the monastery. Mathilde conferred with her few remaining faithful in the late summer of 1092 in Carpineti . The majority spoke out in favor of peace. Only the hermit Johannes from Marola strongly advocated a continuation of the fight against the emperor. Thereupon Mathilde implored her followers not to give up the fight. The emperor's army began to siege Canossa in the autumn of 1092, but withdrew after a sudden failure of the besieged.

In the 1090s Heinrich got increasingly on the defensive. A coalition of the southern German dukes had prevented him from returning to the empire over the Alpine passes. For several years the emperor remained inactive in the area around Verona. In the spring of 1093, Konrad , his eldest son and future heir to the throne, fell from him. Konrad joined the Gregorian camp and the Margravine Mathilde. Sources close to the emperor saw the trigger for the outrage in Mathilde's influence on Konrad, but tradition shows that there was no closer contact between the two before the outrage. A little later, Konrad was taken prisoner by his father. With Mathilde's help, he was freed. With their support Konrad was from Archbishop Anselm III. crowned king of Milan before December 4, 1093. Together with the Pope, Mathilde carried out the marriage of King Conrad with a daughter of King Rogers I of Sicily . This was intended to win the support of the Normans of southern Italy against Henry IV. Konrad's initiatives to expand his rule in northern Italy probably led to tensions with Mathilde. Konrad found no more support for his rule. After October 22, 1097, only his death in the summer of 1101 from a fever is recorded.

In 1094 Heinrich's second wife Praxedis (Adelheid) fled and spread serious allegations against her husband. Heinrich then had her arrested in Verona. With the help of the margravine, Praxedis was able to free herself and find refuge with her. At the beginning of March 1095 Pope Urban II had a synod held in Piacenza under the protection of Mathilde . There Praxedis appeared and complained publicly about her husband "because of the unheard of atrocities of fornication which she had endured with her husband". After the synod, Mathilde probably had no more contact with Praxedis.

Marriage to Welf V. (1089-1095)

At the age of 43, Mathilde married the Bavarian duke's son Welf V, who was no more than 17 years old . However, none of the contemporary sources goes into the great age difference. The marriage was probably concluded at the instigation of Pope Urban II in order to politically isolate Henry IV. According to Elke Goez , the union of northern and southern Alpine opponents of the Salier initially had no military significance, because Welf did not appear in northern Italy with troops. In Mathilde's documents, no Swabian names are listed in the following period, so that Welf could have moved to Italy alone or with a small entourage. According to the Rosenberg Annals, he even came across the Alps disguised as a pilgrim. Mathilde's motive for marriage, despite the large age difference, may also have been the hope for offspring. Late pregnancy was quite possible, as the example of Constance of Sicily shows.

Welf is documented three times as a spouse. In the spring of 1095 the couple separated. In April 1095 Welf had signed Mathilde's certificate for Piadena . The next diploma on May 21, 1095 was already issued by the margravine alone. Welf's name no longer appears in any of the Mathildic documents. As a father-in-law, Welf IV tried to reconcile the couple. He was primarily concerned with the goods of the childless Mathilde. The marriage was never divorced or declared invalid.

Heinrich's withdrawal and new room for maneuver for Mathilde

With the de facto end of Mathilde's marriage, Heinrich regained his capacity to act. Welf IV switched to the imperial side. The emperor locked in Verona was finally able to return to the empire north of the Alps in 1097. After that he never returned to Italy, and it would have been 13 years before his son of the same name set foot on Italian soil for the first time.

In 11th century Italy, the rise of the cities began, in interaction with the overarching conflict. They soon succeeded in establishing their own territories. In Lucca, Pavia and Pisa, consuls appeared as early as the 1080s , which are considered to be signs of the legal independence of the "communities". Pisa sought its advantage in changing alliances with the Salians and the Marquis of Canossa. Lucca remained completely closed to the Margravine from 1081. It was not until Allucione de Luca's marriage to the daughter of the royal judge Flaipert that she gained new opportunities to influence. Flaipert was already one of the Canusiner's most important advisors during Mathilde's mother's lifetime. Allucione was a vassal of Count Fuidi, with whom Mathilde worked closely. Mantua had to make substantial concessions in June 1090. The residents of the city and the suburbs were freed from all “unjustified” oppression and all rights and property in Sacca , Sustante and Corte Carpaneta were confirmed.

After 1096 the balance of power slowly began to change again in favor of the margravine. Mathilde resumed her donations to ecclesiastical and social institutions in Lombardy, Emilia and Tuscany. In the summer of 1099 and 1100 her route led to Lucca and Pisa for the first time. There it can be detected again in the summer of 1105, 1107 and 1111. In the early summer of 1099 she donated a piece of land to the monastery of San Ponziano for the establishment of a hospital. With this donation, Mathilde resumed her relations with Lucca.

After 1090 Mathilde accentuated the consensual rule . After the profound crises, she was no longer able to make political decisions on her own. She held meetings with spiritual and secular greats in Tuscany and also in her home countries of Emilia. She had to take into account the ideas of her loyal friends and come to an agreement with them. In her role as the most important guarantor of the law, she became less and less important to the bishops. They repeatedly asked the margravine to put an end to grievances. As a result, the bishops expanded their position within the episcopal cities and in the surrounding area. After 1100 Mathilde had to repeatedly protect churches from her faithful. The accommodation duties were reduced.

Court culture and domination practice

The yard has developed since the 12th century to a central institution of royal and princely power. The most important tasks were the visualization of the rule through festivals, art and literature. The term “court” can be understood as “presence with the ruler”. In contrast to the Brunswick court of the Guelphs, there are no court offices with Mathilde. Scholars such as Anselm von Lucca , Heribert von Reggio and Johannes von Mantua were around the margravine . Mathilde encouraged some of them to write their works. At her request, Bishop Anselm von Lucca wrote an interpretation of the Psalter , John of Mantua a commentary on the Song of Songs and a reflection on the life of Mary. Works were dedicated or presented to Mathilde, such as the Liber de anulo et baculo of Rangerius of Lucca , the Orationes sive meditationes of Anselm of Canterbury , the Vita Mathildis of Donizo , the miracle reports of Ubald of Mantua and the Liber ad amicum of Bonizo of Sutri . Mathilde contributed to the distribution of the books intended for her by making copies. More works were dedicated only to Henry IV among their direct contemporaries. As a result, the margravine's court temporarily became the most important non-royal spiritual center of the Salier period. It also served as a contact point for displaced Gregorians in the church political disputes. Paolo Golinelli interpreted the repeated admission of high-ranking refugees and their care as an act of Caritas . As the last political expellee, she granted the Archbishop Konrad von Salzburg , the pioneer of the canon reform , asylum for a long time in 1112 . This brought her into close contact with this reform movement.

Mathilde regularly sought the advice of learned lawyers when making court decisions. A large number of legal advisors are named in their documents. There are 42 causidici , 29 iudices sacri palatii , 44 iudices , 8 legis doctores and 42 advocati . According to Elke Goez, Mathildes Hof can be described as "a focal point for the use of learned jurists in the case law by lay princes". Mathilde encouraged these scholars and drew them to their court. According to Elke Goez, the administration of justice was not a scholarly end in itself, but served to increase the efficiency of rulership. Goez sees a legitimation deficit as the most important trigger for the margravine's intensive administration of justice, since Mathilde was never formally enfeoffed by the king. In Tuscany in particular, an intensive administration of justice can be proven with almost 30 placita . Mathilde's involvement in the founding of the Bolognese School of Law, which has been suspected again and again, is viewed by Elke Goez as unlikely. According to Burchard von Ursberg , Irnerius , the alleged founder of this school, produced an authentic text of the Roman legal sources on behalf of Margravine Mathilde. According to Johannes Fried , however, this can at best refer to the Vulgate version of the Digest , and even that is considered unlikely. The role of this scholar in Mathilde's environment is controversial. According to Wulf Eckart Voss, Irnerius has been a legal advisor since 1100. When analyzing the documentary mentions, however, Gundula Grebner came to the conclusion that this scholar should not be classified in the environment of Mathilde von Canossa, but in that of Heinrich V.

Until well into the 14th century, medieval rule was exercised through outpatient government practice. There was neither a capital nor a preferred place of residence for the Canusinians. Rule in the High Middle Ages was based on presence. Mathilde's domain included most of the current double province of Emilia-Romagna and part of Tuscany. Mathilde traveled in her domain in all seasons. She was never alone in this. There were always a number of advisors, clergy and armed men in their vicinity that could not be precisely estimated. She maintained a special relationship of trust with Bishop Anselm von Lucca, who was her closest advisor until his death in May 1086. In the later years of her life, cardinal legates often stayed in her vicinity. They arranged for communication with the Pope. The Margravine had a close relationship with the cardinal legates Bernard degli Uberti and Bonussenior von Reggio . In view of the strains of being in control of the journey, Elke Goez judged that she must have been athletic, persistent and capable. The distant possessions brought a considerable administrative burden and were often threatened with takeover by rivals. Therefore Mathilde had to count on local confidants, in whose recruitment she was supported by Pope Gregory.

In the case of a rulership without a permanent residence, the visualization of rulership and the representation of rank were of great importance. From Mathilde's reign there are 139 documents (74 of which are original), four letters and 115 lost documents ( Deperdita ). The largest proportion of the number of documents are donations to church recipients (45) and court documents (35). In terms of the spatial distribution of the documentary tradition, Northern Italy predominates (82). Tuscia and the neighboring regions (49) are less affected, while Lorraine has only five documents. This is a unique tradition for a princess of the High Middle Ages. A comparably large number of documents does not appear again until the time of Henry the Lion five decades later. At least 18 of Mathilde's documents were stamped with a seal. At the time, this was unusual for lay princes in imperial Italy . There were very few women who had their own seal. The margravine wore two seals of different pictorial types. One shows a female bust with loose, falling hair. The second seal from the 1100s is an ancient gem , not a portrait of Matilda and Godfrey the Hunchback or Welf V. A firm Mathilde for issuing the certificates can be excluded with high probability. To consolidate her rule and as an expression of the understanding of rule, Mathilde referred to her powerful father in her title; it was called filia quondam magni Bonifatii ducis .

The castles in their domain and high church festivals also served to visualize the rule. Mathilde celebrated Easter as the most important act of power representation in Pisa in 1074. The pictorial representations of Mathilde also belong in this context, some of which, however, are controversial. The statue of the so-called Bonissima at the Palazzo Comunale , the cathedral square of Modena , was probably made in the 1130s at the earliest. The princess's mosaic in the church of Polirone was also made after her death. Mathilde had her ancestors put in splendid coffins. However, she did not succeed in bringing together all the bones of her ancestors to establish a central point of reference for rule and memory . The remains of the grandfather remained in Brescello , those of the father in Mantua and those of the mother in Pisa. Their withdrawal would have meant a political retreat and the loss of Pisa and Mantua.

Through the use of the written form, Mathilde supplemented the presence of the immediate presence of power in all parts of her sphere of influence. In her great courts she used the script to increase the income from her lands. Scripture-based administration was still a very unusual means of realizing rule for lay princes in the 11th century.

In the years from 1081 to 1098, however, the Canusinian rule was in a crisis. The documentary and letter transmission is largely suspended for this period. A total of only 17 pieces have survived, not a single document from eight years. After this finding she was not in Tuscany for almost twenty years. However, from autumn 1098 Mathilde was able to regain a large part of the lost territories. This increased interest in receiving certificates from her. 94 documents have survived from its last 20 years. Mathilde tried to consolidate her rule with the increased use of writing. After the death of her mother (April 18, 1076), she often provided her documents with the phrase “Matilda Dei gratia si quid est” (“Mathilde, by God's grace, if she is something”). The personal combination of symbol (cross) and text ("Matilda Dei gratia si quid est") was unique in the personal execution of the certificates. By referring to the immediacy of God, she wanted to legitimize her contestable position. There is no consensus in research about the meaning of the qualifying suffix “si quid est”. This formulation, which can be found in 38 original and 31 copially handed down texts by the Margravine, ultimately remains as puzzling as it is singular in terms of tradition. One possible explanation for their use is that Mathilde was never formally enfeoffed with the margravate by the king. Like her mother Beatrix, Mathilde carried out all kinds of legal transactions without mentioning her husbands and thus with full independence. Both princesses took over the official titles of their husbands, but refrained from masculinizing the titles.

Promotion of churches and hospitals

By opening up the stock of documents, Elke Goez refuted the widespread notion that the margravine had given churches and monasteries rich gifts at all times of her life. There were very few donations initially. Already one year after the death of her mother, Mathilde lost influence on the inner-city monasteries in Tuscany and thus an important pillar of her rule.

The issuance of deeds for monasteries concentrated on convents that were located in Mathilde's immediate sphere of influence in northern and central Italy or Lorraine. The main exception to this was Montecassino . The most important of her numerous donations to monasteries and churches included those to Fonte Avellana , Farfa , Montecassino, Vallombrosa, Nonantola and Polirone. In this way she secured the financing of the old church buildings. She often stipulated that the proceeds from the donated land should be used to build churches in the center of the episcopal cities. This money was an important contribution to the funds for the expansion and decoration of the churches of San Pietro in Mantua , San Geminiano of Modena , Santa Maria Assunta of Parma , San Martino of Lucca , Santa Maria Assunta of Pisa and Santa Maria Assunta of Volterra .

Mathilde supported the construction of the Pisa Cathedral with several donations (1083, 1100 and 1103). Your name should be permanently associated with the cathedral building project. She released Nonantola from paying tithes to the Bishop of Modena. The funds released as a result could be used for the monastery buildings. In Modena, with her participation, she secured the continued construction of the cathedral. Mathilde acted as mediator in the dispute between the cathedral canons and the citizens over the remains of St. Geminianus . The festive consecration took place in 1106. The Relatio fundationis cathedralis Mutinae reports on these processes . Mathilde is presented as a political authority: She is present with an army, gives support, recommends receiving the Pope and reappears for the consecration, during which she dedicates immeasurable gifts to the patron.

Numerous examples show that Mathilde made donations to bishops who were loyal to the Gregorian reforms . In May 1109 she gave land in the area of Ferrara to the Gregorian bishop Landulf of Ferrara in San Cesario sul Panaro and in June of the same year possessions in the vicinity of Ficarolo . The Bishop Wido of Ferrara , however, was hostile to Pope Gregory VII and had written De scismate Hildebrandi against him . The siege of Ferrara undertaken by Mathilde in 1101 led to the expulsion of the schismatic .

On the other hand, nothing is known of Mathilde's sponsorship of nunneries. Their only relevant intervention concerned the Benedictine Sisters of San Sisto of Piacenza, whom they chased out of the monastery for their immoral behavior and replaced with monks.

Mathilde founded and sponsored numerous hospitals to care for the poor and pilgrims. For the hospitals she selected municipal facilities and important Apennine passes. The welfare institutions not only fulfilled charitable tasks, but were also important for the legitimation and consolidation of the margravial rule.

Adopted by Guido Guerra around 1099

In the later years of her life, Mathilde was increasingly faced with the question of who should take over the Canusinian inheritance. She could no longer have children of her own. Apparently for this reason she adopted the Guidi descendant Guido Guerra. On November 12, 1099, he was referred to in a certificate from the princess as her adopted son (adoptivus filius domine comitisse Matilde) . With his consent, Mathilde renewed and expanded a donation from her ancestors to the Brescello monastery . However, this is the only time that Guido had the title of adoptive son (filius adoptivus) in a document that was considered to be authentic . At that time there were an unusually large number of vassals in Mathilde's environment. In March 1100, the Margravine and Guido took part in a meeting of abbots of the order of the Vallombrosan , which they both sponsored . On 19 November 1103 they gave the monastery Vallombrosa possessions on both sides of the Vicano and half of the castle Magnale with the court Pagiano. After Mathilde had bequeathed her property to the Apostolic See in 1102 (so-called second Mathildic donation), Guido withdrew from her. With the donation he lost hope of the inheritance. However, he signed three more documents with Mathilde for the Abbey of Polirone.

From these sources, Elke Goez , for example, concludes that Guido was adopted by Mathilde. According to her, the margravine must have consulted with her loyal followers beforehand and reached a consensus for this far-reaching political decision. Ultimately, pragmatic reasons were decisive: Mathilde needed a political and economic administrator for Tuscany. The Guidi possessions in the north and east of Florence were also a useful addition to the Canusinian possessions. Guido Guerra hoped that Mathilde's adoption would not only give him the inheritance, but also an increase in rank. He also hoped for support in the dispute between the Guidi and the Cadolingians for supremacy in Tuscany. The Cadolinger were named after one of their ancestors, Count Cadalo, who was attested from 952 to 986; they died out in 1113.

Paolo Golinelli doubts this reconstruction of the events. He thinks that Gudio Guerra held an important position among the margravine's vassals, but was not adopted by her. This is also supported by the fact that after 1108 he only appeared once as a witness in one of her documents, namely in a document dated May 6, 1115, which Mathilde issued on the sick bed in Bondeno di Roncore for the benefit of the Polirone monastery .

Mathildic donations

On November 17, 1102 Mathilde donated her property to the Apostolic See at Canossa Castle in the presence of the Cardinal Legate Bernhard von San Crisogono. This is a renewal of the donation, as the first document was allegedly lost. Mathilde had initially transferred all of her property to the Apostolic See in the Holy Cross Chapel of the Lateran before Pope Gregory. Most research has dated this first donation to the years between 1077 and 1080. Paolo Golinelli spoke out for the period between 1077 and 1081. Werner Goez placed the first donation in the years 1074 and 1075, when Mathilde's presence in Rome can be proven. At the second donation, despite the importance of the event, very few witnesses were present. With Atto from Montebaranzone and Bonusvicinus from Canossa, the certificate was attested by two people of no recognizable rank who are not mentioned in any other certificate.

The Mathildische donation caused a sensation in the 12th century and has also received a lot of attention in research. The entire tradition of the document comes from the curia. According to Paolo Golinelli, the transfer from 1102 is a forgery from the 30s of the 12th century; in reality, Mathilde made Heinrich V her only heir in 1110/11. Even John Laudage looks for his study of the sources, the Matilda gift for a fake. Elke and Werner Goez, on the other hand, considered the second deed of donation from November 1102 to be authentic in their document edition. Bernd Schneidmüller and Elke Goez believe that the issuing of a certificate about the renewed transfer of the Mathildic goods was made out of curial fear of the Guelphs. Welf IV died in November 1101. His eldest son and successor Welf V had emilian and Tuscan rulership rights through his marriage to Mathilde. Therefore, reference was made to an earlier award of the inheritance before Mathilde's second marriage. Otherwise, given the spouse's considerable influence, their consent should have been obtained.

Werner Goez explains with different ideas about the legal implications of the process that Mathilde often had her own property even after 1102 without recognizing any consideration for Rome's rights. Goez observed that the donation is only mentioned in Mathildic documents that were created under the influence of papal legates. Mathilde did not want a complete waiver of all other real estate and usable rights and perhaps did not notice how far the consequences of the formulation of the second Mathildic donation went.

Last stage of life and death

In the last phase of her life, Mathilde pursued the plan to strengthen the Abbey of Polirone. The Church of Gonzaga freed them in 1101 from the malos sacerdotes fornicarios et adulteros (" wicked , unchaste and adulterous priests") and gave them to the monks of Polirone. The Gonzaga clergy were charged with violating the duty of celibacy . One of the main evils that the church reformers acted against. In the same year she gave the Abbey of Polirone a poor house that she had built in Mantua; she thus withdrew it from the monks of the monastery of Sant'Andrea in Mantua who had been accused of simony . Polirone Abbey received a total of twelve donations in the last five years of Mathilde's life. So she transferred her property in Villola (16 kilometers southeast of Mantua) and the Insula Sancti Benedicti (island in the Po, today on the south bank in the area of San Benedetto Po) to this monastery. The abbey thus rose to become the house monastery of the Canusines. The monastery chose it as a burial place for itself. The monks used Mathilde's generous donations to rebuild the entire abbey and the main church. Mathilde wanted to secure her memory not only through donations, but also through written memories. Polirone was given a very valuable Gospel manuscript. The book, kept in New York today, contains a liber vitae , a memorial book, in which all of the monastery's important donors and benefactors are listed. This document also deals with Mathilde's memorial. The Gospel manuscript was commissioned by Mathilde; It is not clear whether the codex originated in Polirone or was sent there as a gift from Mathilde. It is the only larger surviving memorial from a Cluniac monastery in northern Italy. Paolo Golinelli emphasized that, through Mathilde's favor, Polirone also became a base where reform forces gathered.

Heinrich V had been in diplomatic contact with Mathilde since 1109. The Salian emphasized his blood relationship with her and demonstratively cultivated the connection. At his coronation as emperor in 1111, disputes over the investiture question broke out again. Heinrich captured Pope Paschal II and some of the cardinals in St. Peter's Church and forced the coronation. When Mathilde found out about this, she asked for the release of the two Cardinals, Bernhard of Parma and Bonussenior of Reggio, who were very close to her. Heinrich complied with her request and released both cardinals. Mathilde did nothing to get the Pope and the other cardinals free. On the way back from the Rome train, Henry V visited the Margravine from May 6th to 8th, 1111 at Bianello Castle . Mathilde achieved the solution from the imperial ban. According to the unique testimony of Donizo, Heinrich transferred the rule of Liguria as viceroyalty to her. At this meeting he also concluded a firm agreement (firmum foedus) with her , which only mentions Donizo and the details of which are not known. In German history since Wilhelm von Giesebrecht, this agreement has been undisputedly interpreted as an inheritance, while Italian historians repeatedly questioned its significance under inheritance law. Luigi Simeoni and Werner Goez have been critical of the assumption of an inheritance . Elke Goez is assuming a standstill agreement. Mathilde, whose health was weakened, probably waived her further support for Pope Paschal II with a view to a good understanding with the emperor. Paolo Golinelli thinks that Mathilde recognized Heinrich as the heir to her property. After his interpretation, the ban against Mathilde was lifted and the margravine reinstated in the northern Italian parts of the formerly large area of Canossa with the exception of Tuscany. Donizo imaginatively embellished this process with the title of viceroy. Some researchers see in the agreement with Henry V a turning away from the ideals of the so-called Gregorian reform, but Enrico Spagnesi emphasizes that Mathilde has by no means given up her church reform -minded policy.

A short time after meeting Heinrich, Mathilde retired to Montebaranzone near Prignano sulla Secchia . In Mantua in the summer of 1114 the rumor that she had died sparked jubilation. The Mantuans strived for autonomy and demanded entry into the margravial castle of Rivalta, five kilometers west of Mantua. When the citizens found out that Mathilde was still alive, they burned the castle down. Rivalta Castle symbolized the hated power of the margravine. Donizo, in turn, used this incident as an instrument to illustrate the chaotic conditions that the sheer rumor of Mathilde's death could trigger. The margravine guaranteed peace and security for him. But Mathilde was able to recapture Mantua. In April 1115, the aging Margravine gave the Church of San Michele in Mantua the rights and income of the Pacengo court. This documented legal transaction proves their intention to win over an important spiritual community in Mantua.

Mathilde often visited the place Bondeno (today Bondanazzo) in the middle of the Po valley, where she owned a small castle, which she often visited between 1106 and 1115. During a stay there, she fell seriously ill, so that she could finally no longer leave the castle. In the last months of her life, the sick margravine was no longer able to travel strenuously. According to Vito Fumagalli , she stayed in the Polirone area not only because of her illness. The House of Canossa had largely been ousted from its previous position of power at the beginning of the 12th century. In her last hours the Bishop of Reggio, Cardinal Bonussenior, stayed at her sick bed and gave her the sacraments of death . On the night of July 24, 1115, Mathilde died of sudden cardiac arrest at the age of 69. After her death, Heinrich succeeded in taking possession of the Mathildic property in 1116 without any apparent resistance from the curia . The once loyal Mathilde accepted Heinrich as their new master without resistance. For example, powerful vassals of the Margravine such as Arduin de Palude, Sasso von Bibianello, Count Albert von Sabbioneta, Ariald von Melegnano, Opizo von Gonzaga and many others came to Heinrich.

reception

High and late Middle Ages

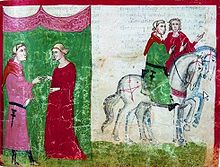

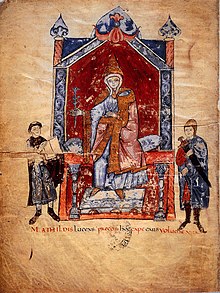

Between 1111 and 1115 Donizo wrote the chronicle De principibus Canusinis in Latin hexameters , a story of the Canusinians, especially Mathilde. Since the first edition by Sebastian Tengnagel , it has been called Vita Mathildis . She is the main source to the margravine. The Vita Mathildis consists of two parts. The first part is dedicated to the early Canusinians, the second deals exclusively with Mathilde. Donizo was a monk in the monastery of Sant'Apollonio. With the Vita Mathildis he wanted to secure eternal memory of the princess. Donizo has most likely coordinated his vita with Mathilde in terms of content including the book illumination down to the smallest detail. However, shortly before the work was handed over, Mathilde died. Text and images on the family history of the Canusiner served to glorify Mathilde, were important for the public staging of the family and were intended to guarantee eternal memory . Positive events were highlighted, negative events were skipped. The Vita Mathildis marks the beginning of a new literary genre. With the early Welf tradition, it establishes medieval family history. The house and reform monasteries, sponsored by Guelph and Canusian women, attempted to organize the memories of the community of relatives and thereby "to express awareness of the present and orientation to the present in the memory of one's own past at the same time". Eugenio Riversi considers the memory of the family epoch, especially the commemoration of the anniversaries of the dead, to be one of the characteristic elements of Donizo.

Bonizo von Sutri gave Mathilde his Liber ad amicum . In it he compared her to her glorification with biblical women. After an assassination attempt on him in 1090, however, his attitude changed because he did not feel sufficiently supported by the margravine. In his Liber de vita christiana he took the view that domination by women was harmful. As examples he named Cleopatra VII and the Merovingian Queen Fredegunde . Rangerius von Lucca also distanced himself from Mathilde when she did not position herself against Henry V in 1111. Out of bitterness, he no longer dedicated his Liber de anulo et baculo to Mathilde, but to John of Gaeta, who later became Pope Gelasius II.

Violent criticism of Mathilde is related to the investiture dispute and relates to specific events. The Vita Heinrici IV. Imperatoris blames her for the apostasy of Conrad from Henry IV. The Milanese chronicler Landulfus Senior made a polemical statement in the 11th century . He accused Mathilde of having ordered the murder of her first husband. She is also said to have incited Pope Gregory to excommunicate the king. Landulf's polemics were directed against Mathilde's partisanship in the battles of Pataria for the archiepiscopal chair in Milan.

Mathilde's tomb was converted into a mausoleum before the middle of the 12th century. For Paolo Golinelli, this early design of the grave is the beginning of the Mathilde myth. In the course of the 12th century two opposing developments occurred: Mathilde's person was mystified, at the same time historical memory of the Canossa event declined. In the 13th century, Mathilde's guilty feelings about the murder of her first husband became a popular topic. The Gesta episcoporum Halberstadensium took it up: Mathilde had confessed to Pope Gregory the murder of her husband, whereupon he had released her from her sentence. Through this act of leniency, Mathilde felt obliged to donate her property to the Holy See. In the 14th century there was a lack of clarity about the historical facts about Mathilde. Only the name of the margravine, her reputation as a virtuous woman, her many donations to churches and hospitals and the transfer of her goods to the Holy See were present. The knowledge of the conflicts between Heinrich and Gregor was forgotten. Because of her connection to the Guidi , Florentine chronicles paid little attention to her, because the Guidi were mortal enemies of the Florentines. For the Nuova Chronica begun by Giovanni Villani in 1306 , Mathilde was a decent and pious person. It emerged from the secret marriage of a Byzantine emperor's daughter to an Italian knight. She did not consummate the marriage with Welf V. Instead, she decided to live her life chaste and pious works.

Early modern age

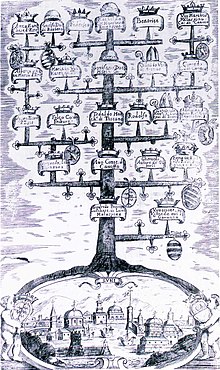

In the 15th century, Mathilde's marriage to Welf V disappeared from chronic and narrative literature. Numerous families in Italy tried rather to claim Mathilde as their ancestress and to derive her power from her. Giovanni Battista Panetti wanted to prove in his Historia comitissae Mathildis that they belonged to the Estonian family . He claimed she was married to Azzo II , the grandfather of Welf V. In his epic Orlando furioso, Ariostus also mentioned Mathilde's alleged relationship with the Estonians. Giovanni Battista Giraldi also assumed a marriage between Mathilde and Azzo II and referred to Ariostus. Many more generations followed this tradition. Only the Estensian archivist Ludovico Antonio Muratori was able to break away from the Estonian family structure in the 18th century. Yet he did not draw a more realistic picture of the margravine. For him she was an Amazon queen . In Mantua, however, Mathilde was captured by the Gonzaga . Giulio Dal Pozzo underpinned Malaspina's claim with his work Meraviglie Heroiche del Sesso Donnesco Memorabili nella Duchessa Matilda Marchesana Malaspina, Contessa di Canossa , written in 1678 .

Dante's Divine Comedy made a significant contribution to the myth . Whether Dante is referring to Mathilde von Canossa, Mechthild von Magdeburg or Mechthild von Hackeborn in the figure Matelda is a matter of dispute. In the 15th century, Mathilde was stylized by Giovanni Sabadino degli Arienti and Jacopo Filippo Foresti as a warrior for God and the Church.

Mathilde reached the climax of the positive assessment in the time of the Counter Reformation and in the Baroque . She rose to become a virtuous heroine and a role model for all of Italy. Pope Urban VIII had her body transferred to Rome in 1630 and she was the first woman to be buried in Saint Peter . Mathilde should serve as a symbol of the triumph of the church over all adversaries for everyone to see. Gian Lorenzo Bernini designed the grave monument, the statue was created by the sculptor Andrea Bolgi . In the dispute between Catholics and Protestants in the 16th century, two opposing judgments were received. From a Catholic perspective, Mathilde was glorified for supporting the Pope. For the Protestants she was responsible for the humiliation of Henry IV in Canossa and was denigrated as a "pope whore" , as in the biography of Henry IV by Johannes Stumpf .

In the historiography of the 18th century ( Lodovico Antonio Muratori , Girolamo Tiraboschi ) Mathilde was the symbol of the new Italian nobility, who wanted to create a pan-Italian identity. Contemporary representations ( Saverio dalla Rosa ) presented her as the Pope's protector.

In addition to the upscale literature, numerous regional legends and miracle stories in particular contributed to Mathilde's subsequent stylization. She was transfigured relatively early from the benefactress of numerous churches and monasteries to the sole monastery and church donor of the entire Apennine landscape. Around one hundred churches are attributed to Mathilde. The myth of the hundred churches developed from the 12th century. Numerous miracles are associated with Mathilde. She is said to have asked the Pope to bless the Branciana fountain . According to a legend, women can get pregnant after a single drink from the well. According to another legend, Mathilde is said to have preferred to stay at the Savignano Castle . There one should see the princess galloping in the sky on full moon nights on a white horse. According to a legend from Montebaranzone, she brought justice to a poor widow and her twelve-year-old son. Numerous legends surround Mathilde's marriages. She is said to have had up to seven husbands and, as a young girl, fell in love with Henry IV.

Modern

In the 19th century, which was enthusiastic about the Middle Ages, the myth was renewed. The remains of Canossa Castle were rediscovered, and Mathilde's whereabouts became popular travel destinations. In addition, Dante's praise for Matelda came back into the spotlight. One of the first German pilgrims to Canossa was August von Platen . In 1839 Heinrich Heine published the poem On the castle courtyard of Canossa stands the German Emperor Heinrich , in which it says: "Peep out of the window above / Two figures, and the moonlight / Gregor's bald head flickers / And the breasts of Mathildis."

In the era of the Risorgimento , the struggle for national unification was in the foreground in Italy. Mathilde was instrumentalized for daily political events. Silvio Pellico stood up for the political unity of Italy. He designed a play called Mathilde . Antonio Bresciani Borsa wrote a historical novel La contessa Matilde di Canossa e Isabella di Groniga (1858). The work was very successful in its time and saw Italian editions in 1858, 1867, 1876 and 1891. French (1850 and 1862), German (1868) and English (1875) translations were also published.

The Mathilde myth lives on in Italy to the present day. The Matildines were a Catholic women's association founded in Reggio Emilia in 1918, similar to the Azzione Cattolica . The organization wanted to bring together young people from the province who wanted to work with the church hierarchy to spread the Christian faith. The Matildines revered Mathilde as a pious, strong, and steadfast daughter of St. Peter. After the Second World War, numerous biographies and novels were written in Italy on Mathilde and Canossa. Maria Bellonci published the story Trafitto a Canossa ("Tormented in Canossa"), Laura Mancinelli the novel Il pincipe scalzo . Local historical publications honor her as the founder of churches and castles in the regions of Reggio Emilia , Mantua , Modena , Parma , Lucca and Casentino .

A large number of communities on the northern and southern Apennines traces their origins and their heyday back to Mathilde's epoch. Numerous citizens' initiatives in Italy organize removals under the motto “Mathilde and her time”. In 1988, Emilian circles unsuccessfully applied for Mathilde's beatification . The place Quattro Castella had its name changed to Canossa out of admiration for Mathilde. Since 1955, the Mathilden Festival at Bianello Castle has been a reminder of Mathilde's meeting with Heinrich V. The organizer is the municipality of Quattro Castella, which has owned the castle since 2000. The ruins on the hills of Quattro Castella have been the subject of a petition for UNESCO World Heritage . Every year on the last Sunday of May there is a festival in Quattro Castella in honor of Mathilde.

Research history

Mathilde receives a lot of attention in Italian history. Mathilden congresses were held in 1963, 1970 and 1977. On the occasion of the 900th return of the events of Canossa, the Istituto Superiore di Studi Matildici was founded in Italy in 1977 and inaugurated in May 1979. The institute is dedicated to the research of all Canusiner and publishes a magazine called Annali Canossani .

In Italy, Ovidio Capitani was one of the best experts on Canusin history in the 20th century . According to his judgment in 1978, Mathilde's policy was “tutto legato al passato”, completely tied to the past, i.e. outdated and inflexible in the face of a changing time. Vito Fumagalli presented several regional historical studies on the Marquis of Canossa . Fumagalli saw the causes of the Canossa's power in rich and centralized allodial goods , in a strategic network of fortifications, and in the support of the Salian rulers. In 1998, a year after his death, Fumagalli's biography of Mathilde was published.

Of the Italian medievalists , Paolo Golinelli has dealt most intensively with Mathilde in the past three decades. In 1991 he published a biography of Mathilde, which was translated into German in 1998. On the occasion of the 900th return of Mathilde's meeting with her allies in Carpineti, a financially supported Congress was held in October 1992 by the Province of Reggio Emilia. The rule of the Canusiner and the various problems of rule in northern Italy of the 10th and 11th centuries were dealt with. The contributions to this conference were edited by Paolo Golinelli. An international congress in Reggio Emilia in September 1997 was devoted to her afterlife in cultural and literary terms. The aim of the conference was to find out why Mathilde attracted such interest in posterity. Until recently, arts and crafts, tourism and folklore were dealt with. Most of the contributions were devoted to the genealogical attempts of the northern Italian aristocracy to connect with Mathilde in the early modern period. Golinelli published the anthology in 1999. An important result of this conference turned out to be that goods and family relationships were ascribed to her that have not been historically proven.

In German historical studies, Alfred Overmann's dissertation formed the starting point for dealing with the history of the margravine. Over 1893 man lay with his investigation at the same time Regesten Mathilde ago. The work was reprinted in 1965 and was published in Italian translation in 1980. In the last few decades Werner and Elke Goez in particular have dealt with Mathilde. From 1986 the couple worked together on the scientific edition of their documents. More than 90 archives and libraries in six countries were visited. The edition was published in 1998 in the Diplomata series of the Monumenta Germaniae Historica . In addition to numerous individual studies on Mathilde, Elke Goez published a biography of Mathilde's mother Beatrix (1995) and emerged as the author of a history of Italy in the Middle Ages (2010). In 2012 she presented a biography of Mathilde.

The 900th year of Henry IV's death in 2006 brought Mathilde into focus in the exhibitions in Paderborn (2006) and Mantua (2008). The 900th anniversary of her death in 2015 was the occasion for various initiatives in Italy. The 21st Congresso Internazionale di Studi Langobardi took place in October of the same year. This resulted in two conference volumes. An exhibition was held at the Muscarelle Museum of Art in Williamsburg from February to April 2015 , the first in the United States on Mathilde.

swell

- Despite all the panegyric, the most important source of information is Donizo's Vita Mathildis . There are several useful issues.

- Donizo von Canossa, Vita Mathildis (De principibus Canusinis), edited by Ludwig C. Bethmann. In: MGH Scriptores 12, Hannover 1856, pp. 351-409 ( digitized version ).

- Vita Mathildis celberrimae Italie carmine scripta a Donizone presbiytero, qui in arce Canusina vixit, ed. Luigi Simeoni (Ludovico Antonio Muratori, RIS ns V / II). Bologna 1940 (facsimile edition of Cod. Vat. Lat. 4922 with edition by Paolo Golinelli and translation into German by Axel Janeck, 2 volumes, Zurich 1984).

- Donizone, Vita di Matilde di Canossa. Edizione, traduzione e note di Paolo Golinelli , con un saggio di Vito Fumagalli , Biblioteca di Cultura Medievale (= Di fronte e attraverso. Vol. 823). Jaca book, Milano 2008, ISBN 978-88-16-40823-4 .

- Elke Goez , Werner Goez (Hrsg.): The documents and letters of Margravine Mathilde von Tuszien (= Monumenta Germaniae historica lay prince and dynasty documents of the imperial period. Vol. 2). Hahn, Hannover 1998, ISBN 3-7752-5433-1 ( online ).

literature

Lexicon article

- Elke Goez: Mathilde von Canossa. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 5, Bautz, Herzberg 1993, ISBN 3-88309-043-3 , Sp. 1017-1019.

- Paolo Golinelli: MATILDE di Canossa. In: Mario Caravale (ed.): Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (DBI). Volume 72: Massimino-Mechetti. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 2009, pp. 114–126.

- Dieter Hägermann : Mathilde of Tuszien . In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages (LexMA). Volume 6, Artemis & Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-7608-8906-9 , column 393 f.

- Herbert Zielinski : Mathilde. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 16, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-428-00197-4 , pp. 378-380 ( digitized version ).

Representations

- Elke Goez: Mathilde von Canossa. Primus-Verlag, Darmstadt 2012, ISBN 978-3-86312-346-8 .

- Werner Goez: Margravine Mathilde von Canossa. In: Ders .: Life pictures from the Middle Ages: The time of the Ottonians, Salians and Staufers. 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1998, ISBN 3-89678-091-3 , pp. 233-254.

- Paolo Golinelli: Matilde ei Canossa nel cuore del medioevo. Camunia, Milano 1991, ISBN 88-7767-104-1 .

- German translation: Paolo Golinelli: Mathilde and the walk to Canossa. In the heart of the Middle Ages. Translated from the Italian by Antonio Avella. Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf et al. 1998, ISBN 3-538-07065-2 .

- Paolo Golinelli (Ed.): I poteri dei Canossa. Because Reggio Emilia all'Europa. Atti del convegno internazionale di studi (Reggio Emilia-Carpineti, 29-31 October 1992). Pàtron, Bologna 1994, ISBN 88-555-2301-5 .

- Paolo Golinelli (Ed.): Matilde di Canossa nelle culture europee del secondo millennio. Dalla storia al mito. Atti del convegno internazionale di studi, Reggio Emilia, Canossa, Quattro Castella, September 25-27, 1997 (= II mondo medievale. Vol. 8). Pàtron, Bologna 1999, ISBN 88-555-2494-1 .

- Paolo Golinelli: L'ancella di san Pietro. Matilde di Canossa e la Chiesa. Jaca Book, Milano 2015, ISBN 978-88-16-41308-5 .

- Matilde di Canossa e il suo tempo. Atti del XXI Congresso Internazionale di Studi sull'Alto Medioevo in occasione del IX centenario della morte (1115–2015), San Benedetto Po, Revere, Mantova, Quattro Castella, 20–24 ottobre 2015, Spoleto (Fondazione Centro Italiano di Studi sull ' Alto Medioevo) 2016 (= Atti dei congressi. Vol. 21). 2 volumes. Fondazione Centro italiano di studi sull'alto Medioevo, Spoleto 2016, ISBN 978-88-6809-114-9 .

- Michèle K. Spike: Matilda of Canossa & the origins of the Renaissance. An exhibition in honor of the 900th anniversary of her death. Muscarelle Museum of Art at the College of William & Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia 2015, ISBN 978-0-9885293-7-3 ( online ).

Web links

- Literature by and about Mathilde von Canossa in the catalog of the German National Library

Remarks

- ↑ Vito Fumagalli: Le origini di una grande dinastia feudale Adalberto-Atto di Canossa. Tübingen 1971, pp. 74-77.

- ^ Elke Goez: Mathilde von Canossa. Darmstadt 2012, pp. 14-16.

- ↑ Elke Goez: The Canusiner - power politics of a northern Italian noble family. In: Christoph Stiegemann, Matthias Wemhoff (ed.): Canossa 1077. Shaking the world. Munich 2006, pp. 117–128, here: p. 119.

- ↑ Elke Goez: The Margraves of Canossa and the monasteries. In: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages 51, 1995, pp. 83–114 ( online ).

- ↑ Arnaldo Tincani: Le Corti dei Canossa in area padana. In: Paolo Golinelli (ed.): I poteri dei Canossa da Reggio all'Europa. Atti del convegno internazionale di studi, Reggio Emilia, October 29–31, 1992. Bologna 1994, pp. 253-278, here: pp. 276-278.

- ^ Elke Goez: Mathilde von Canossa. Darmstadt 2012, p. 57; Elke Goez: Beatrix of Canossa and Tuszien. An investigation into the history of the 11th century. Sigmaringen 1995, p. 13 ( online ).

- ^ Elke Goez: Beatrix von Canossa and Tuszien. An investigation into the history of the 11th century. Sigmaringen 1995, Regest 4f, p. 199 ( online ).

- ^ Elke Goez: Beatrix von Canossa and Tuszien. An investigation into the history of the 11th century. Sigmaringen 1995, Regest 7b, p. 201 ( online ).

- ^ Elke Goez: Beatrix von Canossa and Tuszien. An investigation into the history of the 11th century. Sigmaringen 1995, p. 10 ( online ).

- ^ Lino Lionello Ghirardini: Storia critica di Matilde di Canossa, Problemi (e misteri) della più grande donna della storia d'Italia. Modena 1989, p. 22; Paolo Golinelli: Mathilde and the walk to Canossa, in the heart of the Middle Ages. Düsseldorf / Zurich 1998, p. 110 f.

- ↑ Michèle K. Spike: Matilda of Canossa & the origins of the Renaissance. An exhibition in honor of the 900th anniversary of her death. Williamsburg 2015, p. 51.

- ^ Elke Goez: Mathilde von Canossa. Darmstadt 2012, p. 57; Elke Goez: Beatrix of Canossa and Tuszien. An investigation into the history of the 11th century. Sigmaringen 1995, p. 29 ( online ).

- ^ Elke Goez: Beatrix von Canossa and Tuszien. An investigation into the history of the 11th century. Sigmaringen 1995, Regest 11c, p. 204 ( online ).

- ^ Elke Goez: Mathilde von Canossa. Darmstadt 2012, p. 68 f .; Elke Goez: Beatrix of Canossa and Tuszien. An investigation into the history of the 11th century. Sigmaringen 1995, pp. 20-25; 149 f. ( online ).

- ↑ Donizo II, 18 BC. 1252 f.

- ^ Elke Goez: Beatrix von Canossa and Tuszien. An investigation into the history of the 11th century. Sigmaringen 1995, p. 30 ( online ).

- ^ Elke Goez: Mathilde von Canossa. Darmstadt 2012, p. 79.

- ↑ Roberto Albicini: Un inedito Kalender / obituario dell'abbazia di Frassinoro ad integrazione della donazione di Beatrice, madre della contessa Matilde. In: Benedictina 53 (2006), pp. 389-403; Paolo Golinelli: Copia di calendario monastico da Frassinoro, dans Romanica. Arte e liturgia nelle terre di San Geminiano e Matilde di Canossa. Modena, 2006, pp. 202-203.

- ^ Elke Goez: Mathilde von Canossa. Darmstadt 2012, pp. 80 and 88; Elke Goez: Beatrix of Canossa and Tuszien. An investigation into the history of the 11th century. Sigmaringen 1995, Regest 26, p. 215 ( online ).

- ^ Elke Goez: Beatrix von Canossa and Tuszien. An investigation into the history of the 11th century. Sigmaringen 1995, p. 31 ( online ).

- ^ Elke Goez: Mathilde von Canossa. Darmstadt 2012, p. 82.

- ↑ Elke Goez, Werner Goez (ed.): The documents and letters of the Margravine Mathilde of Tuszien. Hanover 1998, Dep. 13.

- ^ Elke Goez: Welf V. and Mathilde von Canossa. In: Dieter R. Bauer, Matthias Becher (ed.): Welf IV. Key figure in a turning point. Regional and European perspectives. Munich 2004, pp. 360–381, here: p. 363.

- ^ Elke Goez: Beatrix von Canossa and Tuszien. An investigation into the history of the 11th century. Sigmaringen 1995, Regest 25, p. 215 ( online ). For the abbey cf. Paolo Golinelli: Frassinoro. Un crocevia del monachesimo europeo nel periodo della lotta per le investiture. In: Benedictina 34, 1987, pp. 417-433.

- ^ Elke Goez: Mathilde von Canossa. Darmstadt 2012, p. 87; Elke Goez, Werner Goez (ed.): The documents and letters of Margravine Mathilde von Tuszien. Hanover 1998, No. 1.

- ^ Elke Goez: Beatrix von Canossa and Tuszien. An investigation into the history of the 11th century. Sigmaringen 1995, p. 33 ( online ).

- ^ Elke Goez: Mathilde von Canossa. Darmstadt 2012, p. 87; Elke Goez, Werner Goez (ed.): The documents and letters of Margravine Mathilde von Tuszien. Hanover 1998, No. 2.

- ^ Elke Goez: Mathilde von Canossa. Darmstadt 2012, p. 87; Elke Goez, Werner Goez (ed.): The documents and letters of Margravine Mathilde von Tuszien. Hanover 1998, No. 7.

- ^ Elke Goez: Mathilde von Canossa. Darmstadt 2012, p. 93.

- ^ Elke Goez: Mathilde von Canossa. Darmstadt 2012, p. 87; Elke Goez, Werner Goez (ed.): The documents and letters of Margravine Mathilde von Tuszien. Hanover 1998, No. 23.

- ↑ Johannes Laudage: Power and powerlessness of Mathilde of Tuszien. In: Heinz Finger (Ed.): The power of women. Düsseldorf 2004, pp. 97–143, here: p. 97.

- ↑ Michèle K. Spike: Scritto nella pietra: Le "Cento Chiese". Programma gregoriano di Matilda di Canossa. In: Pierpaolo Bonacini, Paolo Golinelli (eds.): San Cesario sul Panaro da Matilde di Canossa all'Età Moderna: atti del convegno internazionale, 9-10 November 2012. Modena 2014, pp. 11–42, here: p. 12 f. ( online ).

- ^ Tilman Struve: Mathilde von Tuszien-Canossa and Heinrich IV. The change in their relationships against the background of the investiture dispute. In: Historisches Jahrbuch 115, 1995, pp. 41–84, here: p. 42 ( online ).

- ↑ See the letter of rejection of the German bishops from January 1076 (MGH Const. 1, p. 106 No. 58 = The letters of Heinrich IV., Ed. Carl Erdmann [Leipzig 1937] Appendix A, p. 68). Paolo Golinelli: Matilde: La donna e il potere. Matilde di Canossa e il suo tempo: Atti del XXI Congresso internazionale di studio sull'alto medioevo in occasione del IX centenariodella morte (1115–2015). San Benedetto Po - Revere - Mantova - Quattro Castella, 20–24 October 2015. 2 volumes. Part 1, Spoleto 2016, pp. 1–34, here: p. 1 ( online ).

- ^ Bonizo, Liber ad amicum , Book 8, 609; Johannes Laudage. On the eve of Canossa - the escalation of a conflict. In: Christoph Stiegemann, Matthias Wemhoff (ed.): Canossa 1077. Shaking the world. Munich 2006, pp. 71–78, here: p. 74.

- ^ Tilman Struve: Mathilde von Tuszien-Canossa and Heinrich IV. The change in their relationships against the background of the investiture dispute. In: Historisches Jahrbuch 115, 1995, pp. 41–84, here: p. 41 ( online ).

- ^ Tilman Struve: Mathilde von Tuszien-Canossa and Heinrich IV. The change in their relationships against the background of the investiture dispute. In: Historisches Jahrbuch 115, 1995, pp. 41–84, here: p. 45 ( online ).

- ^ Elke Goez: Mathilde von Canossa. Darmstadt 2012, p. 113.

- ^ Alfred Overmann: Countess Mathilde von Tuscien. Your possessions. History of their estate from 1115–1230 and their regesta. Innsbruck 1895, Regest 40a. On the battle of Lini Lino Lionello, see: La battaglia di Volta Mantovana (ottobre 1080). In: Paolo Golinelli (ed.): Sant'Anselmo, Mantova e la lotta per le investiture. Atti del convegno di studi (Mantova 23-24-25 maggio 1986). Bologna 1987, pp. 229-240.

- ^ Elke Goez: Mathilde von Canossa. Darmstadt 2012, p. 117 f .; Elke Goez, Werner Goez (ed.): The documents and letters of Margravine Mathilde von Tuszien. Hanover 1998, No. 33.

- ^ Tilman Struve: Mathilde von Tuszien-Canossa and Heinrich IV. The change in their relationships against the background of the investiture dispute. In: Historisches Jahrbuch 115, 1995, pp. 41–84, here: p. 51 ( online ).

- ^ Tilman Struve: Mathilde von Tuszien-Canossa and Heinrich IV. The change in their relationships against the background of the investiture dispute. In: Historisches Jahrbuch 115, 1995, pp. 41–84, here: p. 53 ( online ); Elke Goez: Mathilde von Canossa. Darmstadt 2012, p. 121.

- ^ Elke Goez: Beatrix von Canossa and Tuszien. An investigation into the history of the 11th century. Sigmaringen 1995, p. 171 ( online ).

- ^ Tilman Struve: Mathilde von Tuszien-Canossa and Heinrich IV. The change in their relationships against the background of the investiture dispute. In: Historisches Jahrbuch 115, 1995, pp. 41–84, here: p. 66 ( online ).

- ^ Tilman Struve: Mathilde von Tuszien-Canossa and Heinrich IV. The change in their relationships against the background of the investiture dispute. In: Historisches Jahrbuch 115, 1995, pp. 41–84, here: p. 66 ( online ).

- ^ Tilman Struve: Mathilde von Tuszien-Canossa and Heinrich IV. The change in their relationships against the background of the investiture dispute. In: Historisches Jahrbuch 115, 1995, pp. 41–84, here: p. 70 ( online ).

- ^ Elke Goez: Mathilde von Canossa. Darmstadt 2012, p. 87; Elke Goez, Werner Goez (ed.): The documents and letters of Margravine Mathilde von Tuszien. Hanover 1998, No. 44.