Battle of Marignano

| date | September 13-14, 1515 |

|---|---|

| place | Near Melegnano, southeast of Milan |

| output | Decisive Franco-Venetian victory |

| consequences | De facto end of common federal expansion efforts |

| Peace treaty | " Eternal direction " on November 29, 1516 |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Commander | |

|

|

|

| Troop strength | |

| approx. 16,000 French approx. 17,000 mercenaries approx. 12,000 Venetians, of which approx. 8000 archers, 12,000 horsemen, 74 heavy artillery, over 300 light artillery |

approx. 22,000 confederates, including approx. 3000 free servants, 300 cavalry, 6 light guns |

| losses | |

|

5000-8000 fallen |

9,000-10,000 dead |

League of Cambrai (1508–1510)

Agnadello - Padua - Polesella - Mirandola

Holy League (1510 / 11–1516)

Brescia - Ravenna - Navarra - St. Mathieu - Novara - Guinegate - Dijon - Flodden Field - La Motta - Marignano

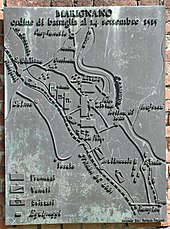

The Battle of Marignano (now Melegnano ) took place on September 13 and 14, 1515 in the Italian Lombardy and was a military conflict between the Confederates and the Kingdom of France over the Duchy of Milan . The defeat at Marignano ended the expansionist efforts of the Swiss Confederation and was one of the last great battles in which the old Swiss Confederation took part. The retreat of the Confederates near Marignano has long been considered the first documented orderly retreat since ancient times . But this representation was contradicted. In 19th century literature, the Battle of Marignano is also referred to as the "Battle of the Giants" ( Italian battaglia dei giganti ).

prehistory

The Old Confederation played at the turn of the 15th into the 16th century temporarily an important role in the clashes for control of Italy . With the help of around 5,000 federal mercenaries, King Ludwig XII conquered . 1499 the Duchy of Milan , to which he raised claims as the grandson of the Milanese Princess Valentina Visconti , daughter of Duke Gian Galeazzo Visconti . In the following year, the Duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza (“il moro”), succeeded in recapturing his duchy, also with the help of around 5,000 federal mercenaries. In Novara, it finally came to the meeting of two armies from Swiss mercenaries in the service of France and Milan, as the Federal Diet , the " Reislauferei " as mercenaries was then called, was unable to bring under control. The siege of the city of Novara by around 10,000 confederates in the service of France ended with the so-called " betrayal of Novara ": Ludovico Sforza was betrayed by his federal mercenaries and died in 1508 in French captivity. In the service of France, around 6,000 federal mercenaries also subjugated Genoa for France in the spring of 1507 . Nevertheless, Louis XII renewed. In 1509 the pay alliance with the Confederates, which had been the basis for his successes in Italy since 1499, did not.

Pope Julius II , the declared opponent of the French expansion to Italy, won the Confederations on March 14, 1510 through the mediation of the Bishop of Sion, Cardinal Matthäus Schiner , for a pay alliance that allowed him to recruit 6,000 mercenaries in the Confederation and in Valais allowed. However, in September 1510, the Diet prevented these troops from being deployed against France (→ Chiasser Zug ). In 1511 the Pope succeeded in uniting France's opponents in the Holy League . These were the Roman-German Emperor Maximilian I von Habsburg , the Republic of Venice and the Kingdom of Aragon . Even in the Confederation, there was now a change of opinion against France, since Louis XII. refused to pay compensation for the murder of two federal envoys on his territory. A first campaign by around 10,000 Swiss Confederates to Milan, the so-called «Cold Winter Campaign» in 1511, was broken off without success. It was not until April 30, 1512 that the Federal Diet decided to launch another military campaign into Lombardy, after negotiations with Louis XII. about a renewal of the pay alliance of 1499 had failed because it wanted to pay too little after its victory over the Holy League at Ravenna (April 11, 1512). Around 18,000 Confederates therefore moved to Lombardy in the so-called "Great Pavierzug" in the summer of 1512 and reinstated the son of Ludovico Sforza, Maximilian Sforza , in his duchy in December . As a thank you for the service rendered, i.e. the expulsion of the French, Cardinal Matthäus Schiner presented the Confederates with 42 banners on behalf of the Pope, which went down in history as the " Julius banner" . Milan was now a protectorate of the Swiss Confederation and had to compensate for its protection with trade privileges and annual payments of 40,000 ducats. Large areas south of the Alps went to the Confederates and their allies as "Ennetbirgische Vogteien". All Alpine passes between the Stilfserjoch and the Great St. Bernhard were thus under direct control of the Swiss Confederation. The supremacy of the Confederation in Lombardy was confirmed by a brilliant victory against an attack by French and Venetian troops at the Battle of Novara on June 6, 1513. The Swiss Confederation then declared war on France in August and invaded Burgundy . On September 13, 1513, Louis XII declared himself. ready for peace and assured the confederates in the Treaty of Dijon the Duchy of Milan. Since the federal troops withdrew without waiting for the ratification of the treaty, Ludwig later revoked the treaty.

The successor to Louis XII, Francis I of France, continued to try to enforce France's claims to Milan. At first he negotiated unsuccessfully with the Confederates in order to obtain a return without a fight. He offered 400,000 kroner, which had been provided for in the Treaty of Dijon, if the Confederates allowed him to conquer the Duchy of Milan. They rejected the offer. When Francis I then went to Lombardy in the spring of 1515 with a considerable army of around 55,000 infantry and cavalry , the Diet sent around 18,000 men across the Alps to protect Milan in April / June 1515. Despite his superiority, Francis I continued to negotiate with the Confederates. On September 8, 1515, Francis I and a part of the Confederates concluded the Treaty of Gallarate , which provided:

- France pays the Confederation the 400,000 kroner of the Dijon Treaty and 300,000 kroner each for the cost of the campaign and for the evacuation of the occupied Milanese territories, so a total of 1,000,000 kroner. In return, the confederates renounce their rights in Milan and give up their role as protector of Duke Maximilian Sforza.

- The Milanese Duke Maximilian Sforza is to receive a French duke title as a severance payment.

- All conquered areas in Ticino go back to the Duchy of Milan, but Francis I recognizes the federal assets of 1500 in Ticino: Leventina , Blenio , Riviera and Bellinzona .

As a result, a total of around 10,000 men withdrew from Bern , Solothurn , Freiburg , Biel / Bienne and the Valais , as they were in favor of accepting the French proposals.

Course of the battle

A skirmish outside the gates of Milan led the Confederates to attack the French on September 13th. The papal legate and Cardinal Matthäus Schiner , who encouraged the Confederates to attack , probably played an important role . The battle began unusually late around 3 p.m. Divided into three groups of violence - in the middle the cantons of Central Switzerland, on the right the Zurich, left the Lucerne and Basler - the Confederates penetrated deep into the French army camp with around 20,000 men and held their own there until late at night. Since the battle was undecided, both armies bivouacked on the battlefield. When the battle resumed the next day, the Venice Light Horse , led by the experienced condottiere Bartolomeo d'Alviano , brought the decision when they went into battle at 10 o'clock, shouting "San Marco!" Around noon the remaining Confederates retreated towards Milan with the wounded, flags and guns. The majority of the approximately 12,000 to 14,000 fallen were confederates.

The retreat of the Confederates near Marignano is considered to be one of the first documented, organized retreats since ancient times. However, this representation was contradicted. So wrote NZZ -Redaktor Andres Wysling in an article of 20 March 2015 a "Swiss Marignano myth". The Duke of Milan had ordered a retreat, but it did not materialize because the troops could not find each other. Some persevered, others independently sought an escape. The withdrawal began as a panic escape. Only when French troops gave the Swiss escorts because the Venetian horsemen were chasing them did "something like an easy order" emerge. Confederates who were scattered and who did not succeed in joining the main troop were wiped out. Even Lombard farmers attacked Confederates who were wandering aimlessly.

The Swiss painter Ferdinand Hodler heroized the battle in his famous fresco in the Swiss National Museum (Zurich). The victory of the French was not only due to their numerical superiority, but also to the tactical skill with which Francis I, intuitively using the internal disagreement of the enemy, split the federal forces and thus decisively weakened them. The defeat of Marignano remains the most significant event in Swiss military history in terms of numbers, but also in terms of its historical effects.

Consequences of the battle

Most of the federal towns wanted to continue the war against France even after the defeat at Marignano. On September 24, the Diet decided to send a further 22,000 men to Lombardy. However, only the central Swiss cantons sent some contingents, which were then also called back soon. On October 4th, Milan fell into the hands of France after the surviving Swiss withdrew without a fight and Duke Maximilian Sforza abdicated for a pension of 30,000 ducats. On November 7th, through the mediation of Duke Karl III. of Savoy, the Peace of Geneva between France and the Confederation was achieved, but this was rejected by Uri, Schwyz, Zurich, Basel and Schaffhausen. In March 1516, these places therefore made 15,000 men available to the Roman-German Emperor Maximilian I for his campaign to Northern Italy. Since the other places adhered to the Treaty of Geneva and the French even sent 6,000 men reinforcements, a new fratricidal war threatened the mercenaries of the various federal places. However, since the emperor could not raise the agreed pay payments, the confrontation did not take place.

On November 29, 1516, the Swiss Confederation and France finally signed a peace treaty known as the "Eternal Direction" , in which all previous hostilities were abolished and a court of arbitration should be set up for future conflicts. Neither contractor was to support the other's enemies, and the Confederates were allowed to keep their conquests in Italy with the exception of the Ashen valley. As compensation for the war, Francis I paid another 700,000 crowns to the thirteen towns in the Confederation . Milan returned to France until it came to the Habsburgs in 1521 after the Battle of Bicocca . Another alliance that the Swiss Confederation (except Zurich) concluded with France in 1521 allowed France to recruit up to 16,000 Swiss mercenaries in return for annual payments, trade freedoms and other advantages. The confederates thus placed themselves entirely at the service of the French court and renounced an independent role in European politics.

The battle was a turning point in Swiss warfare, as it proved that the infantry, in the form of mercenary troops, was no longer the only weapon that decided the war. Due to the "Eternal Direction" with France, the Swiss lost their position as an independent great power . However, federal mercenaries continued to fight in the French army in northern Italy.

Also participating in the battle was the Toggenburg and later Zurich reformer Huldrych Zwingli in his capacity as a Catholic priest of Glarus. He belonged to the Glarus army. Soon afterwards he began to preach against the “red hats” (= “red hats”), by which he meant in particular his former friend Cardinal Matthäus Schiner, in whom he saw, not completely wrongly, one of the main warmongers. Indirectly, the Battle of Marignano also contributed to getting the Reformation going in Zurich.

After Marignano the confederates did not pursue any further expansion policy, not even a common foreign policy. Because of the denominational split in the alliance, they were no longer able to develop uniform positions. But as early as the 15th century, different geographical thrusts had made the pursuit of common foreign policy goals very difficult.

In the 19th century the defeat of Marignano was interpreted as the beginning of the Swiss policy of neutrality . This view of the battle is also expressed in the inscription Ex Clade Salus ("Salvation from defeat") on the 1965 monument.

Monuments and memorials

- In 1965, on the occasion of the 450th anniversary of the battle, a memorial by the Schwyz sculptor Josef Bisa was erected in Zivido on behalf of a Swiss committee . It bears the inscription Ex Clade Salus ("Salvation from defeat") first formulated at the time by one of the initiators of the monument, the Zurich pastor Peter Vogelsanger .

- In the hamlet of Mezzano near Melegnano there is the Ossario Santa Maria della Neve , in which the bones of the fallen are kept.

- The French Renaissance composer Clément Janequin put the battle of Marignano and the victory of Francis I over the confederates into music in the chanson La guerre .

- In 1939 Jean Daetwyler composed a military march on behalf of the Central Valais Music Association, which he named "Marignan".

- In memory of the battle, a street in San Giuliano Milanese was named Via dei Giganti ("Street of the Giants").

literature

- AA.VV .: Volti di una guerra. 1515 Marignano. Museo nazionale svizzero, Zurigo 2015.

- Hans Delbrück : History of the Art of War. The Modern Age. Reprint of the first edition from 1920. Nikol, Hamburg 2003, ISBN 3-933203-76-7 .

- Hervé de Weck: Marignano, Battle of. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . 2009 .

- Ruben Rossello, Marino Viganò (Ed.): Il cielo di Marignano. Dalla battaglia alla docufiction della Televisione svizzera. 13/14 September 1515–2015. Fondazione Trivulzio-Chiasso, SEB Società Editrice 2015.

- Walter Schaufelberger : Marignano. Structural limits of federal military power between the Middle Ages and modern times. Huber, Frauenfeld 1993, ISBN 3-7193-1038-8 .

- Markus Somm : Marignano. The story of a defeat. Stämpfli, Bern 2015, ISBN 978-3-7272-1441-7 ( preprint ).

- Emil Usteri: Marignano. The fateful years 1515/1516 in the field of view of the historical sources. Report house, Zurich 1974, ISBN 3-85572-009-6 .

Web links

- Hervé de Weck : Marignano, Battle of. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Meinrad Lienert : The battle of Marignano, Swiss sagas and heroic stories. Stuttgart 1915. On haben.at, databases on European ethnology / folklore

- Pro Marignano Foundation

- Hooray, lost! 499 years of Marignano

- The battle for Marignano. Day indicator

- Hans Conrad Zander : 14.09.1515 - The battle at Marignano WDR ZeitZeichen (podcast).

- "The smell of the decaying spread in all directions"

Individual evidence

- ↑ Winfried Hecht: The Julius banner of the town facing Rottweil. In: Der Geschichtsfreund: Messages from the Central Switzerland Historical Association . 126/7 (1973/4). doi : 10.5169 / seals-118647

- ↑ With halberds against cannons: Blind into perdition - Marignano 1515 . In: NZZ , March 20, 2015

- ^ A b Andres Wysling: Retreat under the protection of the French . nzz.ch, March 20, 2015; accessed on July 13, 2015.

- ↑ Andres Wysling: “Battle of the Giants” , nzz.ch, March 20, 2015, accessed on July 13, 2015.

- ↑ Thomas Maissen : History of Switzerland. here + now, Baden 2010, ISBN 978-3-03919-174-1 , p. 98.

- ^ Andres Wysling: Marignano - on the battlefield of urban planning , nzz.ch, July 10, 2015, accessed on July 13, 2015.