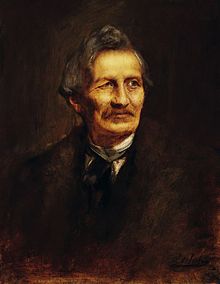

Gottfried Semper

Gottfried Semper (born November 29, 1803 in Hamburg , † May 15, 1879 in Rome , Italy) was a German architect and art theorist in the mid-19th century. He is considered a representative of historicism , especially the neo-renaissance , and a co-founder of modern theater architecture .

Life

Young years (until 1834)

Gottfried Semper was the son of the wealthy wool manufacturer Gottfried Emanuel Semper (1768–1831) from Landeshut in Silesia, who had come to Hamburg as a child, and Johanna Marie née Paap (1771–1857), who came from a Huguenot family . After the marriage, Gottfried Emanuel Semper took over the management of the wool factory JW Paap, which was founded in Altona in 1651 and is famous throughout Europe and belongs to his wife's family. Gottfried Semper was born in Hamburg in the back yard of an apartment building on Neuer Wall 164 (today 80–84) and baptized reformed in Altona, which was then Danish . He was the fifth of eight children. Shortly afterwards the family moved into their own house on the "Hopfensack". After the French occupation of Hamburg in 1806, the family moved to Altona. He was prepared for grammar school by Pastor Mielck in Barmstedt and from 1819 he attended the Hamburg school of scholars at the Johanneum . In 1823/1824 he studied mathematics and history at the University of Göttingen . After an unsuccessful attempt to get a job as a trainee at the Düsseldorf Hafen- und Wasserbauten in 1825 , he enrolled in the architecture class of the Munich Art Academy at the end of the year without, however, undertaking any serious studies.

Extensive hikes led him through Germany in 1826 ( Heidelberg , Würzburg , Regensburg ), in December 1826, after a duel with Harro Harring, he had to flee to Paris , where he worked for Jakob Ignaz Hittorff and Franz Christian Gau , the city's famous architects of German origin. Here he worked concentrated on several study drafts. In Paris he also got to know the scientific collections of the Jardin des Plantes , which impressed him very much.

In 1828 he began to work as a trainee in port construction in Bremerhaven , but in 1829 he traveled to Paris for another study visit. There he experienced the July Revolution of 1830 with great enthusiasm . In August 1830 he left for Italy and was in Rome at the end of November. In February 1831 he was in Pompeii and a little later left for Sicily with six French architects to study the temples of Agrigento, Selinunte and Segesta. He then went to Greece with the French architect Jules Goury, where Friedrich Thiersch gave him diplomatic status so that he could visit the temples of Aegina. In vain, however, he hoped for a job at the residence designed by Leo von Klenze for King Otto of Greece. In 1832 he was involved in archaeological research on the Athens Acropolis for four months . He was particularly interested in the question raised in the Biedermeier period as to whether the buildings of the Greeks and Romans were brightly painted or not ( polychrome dispute ). When he returned to Rome, he managed to detect traces of color on all parts of the Trajan Column. He sent samples to his brother Wilhelm, a pharmacist in Altona, for chemical analysis. His reconstructions of the picturesque furnishings of ancient villas made in Italy inspired his later designs for the decorative paintings in Dresden and Vienna. In 1834 his work Preliminary Remarks on Painted Architecture and Sculpture with the Ancients appeared , in which he clearly took a stand for polychromy, which he underpinned by his color studies on the Trajan Column in Rome. His theses received the approval of Karl Friedrich Schinkel , but also earned him the opposition of the art theorist Franz Kugler .

In 1833 he received his first building contract in Rome from the merchant and banker Conrad Hinrich Donner , for whom he built a small private museum on his country estate in Altona (today Hamburg-Ottensen ). This was to be Semper's first museum building, for which the Danish architect CF Hansen was originally intended. The pavilion for the private sculpture collection , crowned by an octagonal dome, combined a greenhouse in an iron and glass construction and a small orangery . Even then, Semper tried to find the best possible lighting for the exhibits. The question of optimal lighting should also be of central importance for all of his other gallery and museum buildings. Gottfried Semper was a member of the Hamburg Artists' Association from 1832 .

Time in Dresden (1834 to 1849)

Through Franz Christian Gau, with whom he had worked in Paris, and on the recommendation of Schinkel, Semper was appointed professor of architecture at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Dresden on May 17, 1834 and was appointed to this position on September 30 introduced. Gottfried Semper's pupils at the art academy included Ludwig Theodor Choulant (1827–1900), Adolf Heinrich Lier and Oskar Mothes .

He swore the oath of subjects to the Saxon King Anton the Kind and thus became a Saxon citizen. He became director of the Dresden Building School and a member of the Saxon Art Association . In Dresden he also joined the Masonic lodge To the three swords and Astraea to the green diamond .

On September 1, 1835, Semper married the major daughter Bertha Thimmig, who gave birth to a total of six children between 1836 and 1848.

In Dresden, Semper was a member of a large number of artistic and literary associations. In addition to the Saxon Art Association, he belonged to the circles around Johann Gottlob von Quandt , Martin Wilhelm Oppenheim and Julius Mosen , was a member of the Hiller-Kränzchen and Hillers Salon and, with Richard Wagner, in the pre-revolutionary Monday Society , the Albina and the Fatherland Association .

In 1837 he presented the first drafts for an extension of the Zwinger (Zwingerforum) and a court theater. From this, the first Royal Court Theater , which opened in 1841 (burned down in 1869), was carried out over the next few years . The plans for the kennel forum were revised several times, but not implemented. Instead, it was decided in 1846 to close the Zwinger to the northeast with a picture gallery. Semper traveled to Italy to get to know galleries there. The draft presented by him was accepted for execution, and construction work began as early as the summer of 1847. After Semper's escape from Dresden in 1849 because of participation in the Dresden May Uprising , the master builder Karl Moritz Haenel was given the task of completing the building (by 1855). The resulting plaza between the Zwinger, the Catholic Court Church and the castle through the construction of the picture gallery and the court theater still impresses today as an effective ensemble.

around 1860 by Louis Thümling

In addition to these large orders, other buildings were built that are inextricably linked with his name, such as the Maternihospital , the Dresden synagogue ( destroyed during the Nazi era ) , the Oppenheim City Palace and the one built for the banker Martin Wilhelm Oppenheim (1781–1863) Villa Rosa . The latter is considered a prototype of German villa architecture.

After the Hamburg fire in 1842, Semper was in Hamburg from May 21 to 28 and submitted his construction plan as a variant of Lindley's first plan , which, in Semper's view, lacked an "artistic trait". Semper's ideas did not come to fruition directly, but were partly taken up in Chateauneuf's construction plan .

The German Revolution also reached Dresden in May 1849, where the Dresden May Uprising broke out. Gottfried Semper and his friend Richard Wagner fought as staunch Republicans for basic civil rights. As a member of the Dresden Municipal Guard, Semper had barricades rebuilt so that they could be defended more efficiently. However, although requested, he did not join the Provisional Government as he considered this to be incompatible with his oath of subjects. The uprising finally failed on May 9, 1849. Semper fled via Pirna and Zwickau and reached Würzburg on May 16. On the same day, the new government issued a profile against the "first class democrat" and "chief ringleader" Semper. His family initially stayed in Dresden.

Although Semper's reputation as an architect was mainly based on his designs and buildings in Dresden, Semper turned his back on Dresden forever. It was not until 14 years later, in 1863, that the Saxon government lifted the profile against him. Semper was also spied on by the Saxon police later in England and Zurich . When the first court theater built by him fell victim to a fire in 1869 and Saxony's King Johann commissioned him to build the second at the urging of the citizens, he provided the plans, but his son Manfred Semper , who was also an architect, took over the construction management .

After Semper's escape, the architect Hermann Nicolai succeeded him in the summer of 1850 as professor of the construction atelier of the Academy of Fine Arts. Nicolai taught a style of the Saxon Neo-Renaissance in Dresden until his death in 1881, which was further spread by many of his students as the so-called Semper Nicolai School .

Post-Revolutionary Period (1849 to 1855)

Semper fled via Zwickau, Hof , Karlsruhe and Strasbourg, first to Paris and then to London . He stayed in Paris until the autumn of 1850, but was unable to establish a secure existence. He drafted a synagogue there, but the construction was never carried out. Although he initially had the plan to emigrate to America , he broke with this plan again when he was already on the ship for the crossing. The reason for this was an activity promised to him in England. So he met Henry Cole (1808-1882), head of the School of Designs , in London. This gave him the opportunity to teach at the Department of Practical Art at the School of Designs in 1852 . It was also through Cole that Semper met Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha , the Prince Consort of Queen Victoria of England . He wanted to build a cultural forum ("Albertopolis") on the area in South Kensington, which was bought with the proceeds from the world exhibition , and asked Cole and Semper to work out plans for it. In 1855 Semper submitted his designs and the prince was very impressed. However, they were never carried out as they were rejected by the Board of Trade as too financially risky.

Again on Cole's recommendation, he was commissioned to set up the departments of Canada, Turkey, Egypt, Sweden and Denmark at the Crystal Palace . Otherwise, Semper managed to get by with odd jobs (World Exhibition 1851, hearse for the Duke of Wellington 1852). Due to the lack of opportunity to work as an architect, Semper concentrated on his theoretical work. Preparatory work was carried out for his later major work The Style in the Technical and Tectonic Arts or Practical Aesthetics , which finally appeared in two volumes in 1860 and 1863. In 1851 he published The Four Elements of Architecture and in 1852 Science, Industry and Art . In 1855, Semper went to Zurich on the mediation of Richard Wagner .

Time in Zurich (1855 to 1871)

On February 7, 1855, the Swiss Federal Council appointed Semper professor for life. From 1855 he worked as a professor of architecture at the new polytechnic and many of his students, such as Alfred Friedrich Bluntschli , Johann Rudolf Rahn and Theophil Tschudy , later contributed to his international fame - not without self-interest, because most of the Semper students from Zurich were famous and successful themselves Become an architect. The payment allowed Semper to bring his family from Saxony to Zurich.

The Swiss Confederation was planning after the founding of the modern state in 1848, a pan-Swiss Polytechnic to set up in Zurich. As an expert, Semper assessed the designs for a university building that had now been submitted to an architectural competition , declared them unsatisfactory and developed their own concept; this was to be repeated later in Vienna. Proudly placed and clearly visible from all sides on a terrace above Zurich's old town , where fortifications had been standing shortly before, the new federal educational institution symbolized the beginning of a new era. The main building, erected between 1858 and 1864, which is still reminiscent of Semper despite many renovations, initially had to accommodate not only the newly established Polytechnic (since 1911 Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich , ETH) but also the existing Zurich University .

Semper’s other buildings in Switzerland include the Federal Observatory (1861–1864) in Zurich and the town house (1865–1869) in Winterthur . His main theoretical work The Style in the Technical and Tectonic Arts or Practical Aesthetics was also created in Zurich.

In 1861, the Swiss municipality of Affoltern am Albis granted Semper citizenship in return for planning the reconstruction of the church tower. This civil right was confirmed by the Zurich cantonal government in December 1861. Equipped with Swiss passports, Semper was able to travel to Germany again.

Semper designed a design for a Richard Wagner Theater in Munich for King Ludwig II of Bavaria . The plans for the Festspielhaus from 1864 to 1866 remained unrealized; the conception of the two monumental festival staircases as transverse wings, which is unusual in the theater building, was incorporated into the later construction of the Vienna Burgtheater . In 1866 Semper was appointed a foreign member of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences .

Time in Vienna (from 1871)

As early as 1833 there were first plans for the public presentation of the Imperial Art Collections in Vienna. With the plans for Vienna's Ringstrasse in 1857, the museum question became acute again. The exhibits of the imperial art collections were housed in different buildings and the natural objects collections eke out their existence in the cramped rooms of the Hofburg . With regard to the establishment of museums (though via museums for the art industry), Semper had written a work in English in London in 1852, the manuscript of which he donated to the Austrian Museum for Art and Industry (now the Museum of Applied Arts Vienna ) in 1867 . It is kept in the MAK library and works on paper collection. When, after two competitions for the museums (1866 and 1867), a satisfactory solution was still not found, the call for an international jury was loud and the name Semper was mentioned more and more often. Certainly his plans for the Zwinger Forum in Dresden - albeit never executed - played a decisive role here as well. Semper's plans were well known in Viennese architectural circles, and about 1844 they were reported in the Allgemeine Bauzeitung .

In 1869 the k. & k. Chief Chamberlain Count Franz Folliot de Crenneville Semper asked to examine the submitted competition plans.

Semper submitted a detailed report on March 11, 1869, in which he rejected both plans and proposed his own concept (with the Hofburg as the focus). After a personal interview with Emperor Franz Joseph I , he was commissioned to make a proposal for new buildings on Vienna's Ringstrasse. In 1869 he designed a huge " Kaiserforum ", which was only partially realized. As a result of his plans, the Kunsthistorisches and the Naturhistorisches Hofmuseum as well as a new throne room were built in front of the Vienna Hofburg .

In 1871 Semper moved to Vienna because of these orders. At the request of Emperor Franz Joseph I, however, he had to choose an employee who was familiar with the conditions in Vienna (preferably from the ranks of the competition architects). Semper's choice fell on Carl von Hasenauer , whose design he revised in line with his overall concept. Not least because of this, during the construction work between Semper and Hasenauer there were repeated disputes about the authorship of the designs. Ferdinand von Fellner-Feldegg (1855–1936) published an article in the newspaper Der Architekt in 1895 , in which he attributed the authorship of the designs to Gottfried Semper. In 1876, Semper therefore ended his collaboration on this project. In the meantime, however, he had been awarded the Prussian order pour le mérite for science and the arts on May 31, 1874 because of his artistic works, which, according to Schinkel , made him the most important architect in the German-speaking area . In the following year, Semper had to cope with health problems. Two years later, at the age of 75, he died on a trip in Italy . Gottfried Semper was buried in the Protestant cemetery at the Cestius pyramid in the Testaccio district of Rome .

family

Gottfried Semper married Bertha Thimmig (1810–1859) in Dresden in 1838. From this marriage there were four sons and three daughters:

- Elisabeth (1836–1872), married to the lawyer Heinrich Mölling

- Manfred (1838–1913), architect

- Conrad Julius Herrmann (1841–1893), factory owner in Philadelphia

- Anna (1843–1908), married to the historian Theodor von Sickel

- Hans (1845–1920), art historian

- Emanuel (1848–1911), sculptor

plant

The Dresden Court Theater , which burned down in 1869, was Semper's first major work and established his fame as an architect. His artistic goal of having the function and internal structure of a building reflected in its external appearance proved to be trend-setting for theater construction in the 19th century. He tied in with the reform efforts of Friedrich Gilly , Carl von Fischer and Karl Friedrich Schinkel. The Italian High Renaissance served as a model for him . He was based primarily on large Roman buildings (such as the Colosseum ), in which he saw the major construction tasks of the 19th century (e.g. theater and train station) most likely fulfilled.

In addition, Semper is considered to be one of the most important connoisseurs of textile architecture since prehistory ( tents , yurts , circus buildings ).

Buildings and designs (selection)

- in Bautzen

- in Dresden

- Maternihospital - 1837/1838

- Court Theater - 1838–1841 (burned down in 1869)

- Villa Rosa - 1839 (badly damaged in World War II, later demolished)

- Synagogue - 1839–1840 (destroyed on November 9, 1938)

- Palais Kaskel-Oppenheim - 1845–1848 (blown up in 1951)

- Semper Gallery - 1847–1855

- Neues Hoftheater (Semperoper) - 1871–1878 (heavily destroyed in World War II, reopened in 1985 after being built true to the original)

- in Branitz (near Cottbus)

- Expansion of Branitz Castle 1847–1849

- in Schwerin

- Schwerin Palace - 1845–1857 (together with Friedrich August Stüler , Georg Adolf Demmler and Ernst Friedrich Zwirner )

- in Zurich

- Town house - 1858 (unrealized competition design)

- Polytechnic , today ETH - 1858–1864

- Federal observatory

- Washboat - 1862–1864

- in Winterthur

- Townhouse - 1865–1869

- Catholic Church Neuwiesen - 1864 (unrealized competition design)

- in Vienna (all work together with Carl von Hasenauer )

-

Kaiserforum in Vienna, this contains:

- Kunsthistorisches Museum - 1872–1881, completed in 1891

- Natural History Museum Vienna - 1872–1881, completed in 1889

- New Hofburg - 1881–1913

- Burgtheater - 1873–1888

- Semper Depot - 1874–1877 (formerly production site for theater decorations and sets)

-

Kaiserforum in Vienna, this contains:

Fonts (selection)

- Preliminary remarks on painted architecture and sculpture among the ancients. Altona 1834. Digitized version (PDF; 16.07 MB) at the ETH Library ; Digitized at the Bavarian State Library .

- The four elements of architecture. Braunschweig 1851. Digitized version (PDF; 15.9 MB).

- Science, industry and art. Braunschweig 1852 digitized version (PDF; 4.1 MB)

-

The style in the technical and tectonic arts or practical aesthetics. Frankfurt am Main / Munich 1860–1863. Digital version of volume 1 (PDF; 138.58 MB), digital version of volume 2 (PDF; 140.44 MB).

- (Reprinted 1977), ISBN 3-88219-020-5 .

-

Small fonts. Berlin / Stuttgart 1884. Digitized version (PDF; 147.48 MB).

- (Reprinted 1979 and 2008)

Honors

- Gottfried Semper Monument in Dresden (next to the art exhibition building on Brühl's Terrace) by Johannes Schilling

- Monument in Zurich (in front of the northwest corner of the Semper building of the ETH )

- Monument in Hamburg. The architect and builder Franz Bach (1865–1935) from Langendorf near Weißenfels received permission from Semper's eldest son to name his office building (1905–1907) at Spitalerstraße 10 Semperhaus . In 1907 a life-size seated statue of Gottfried Semper made of bronze was inaugurated in the entrance hall, which was created by Semper's youngest son, Emmanuel Semper.

- On his 200th birthday in 2003, Deutsche Post issued a special postage stamp.

Locations

Gottfried Semper School Elementary and community school in the city of Barmstedt

- 25355 Barmstedt

Gottfried-Semper-Strasse in

- 06124 hall

Gottfried-Semper-Weg in

- 95444 Bayreuth

Semperstrasse in

- 12159 Berlin (since 1914)

- 33739 Bielefeld

- 44801 Bochum, Germany

- 09117 Chemnitz

- 44269 Dortmund

- 01069 Dresden

- 45138 Essen (from 1908)

- 22303 Hamburg (from 1907)

- 04328 Leipzig (from 1938)

- 81735 Munich

- 26127 Oldenburg

- 66123 Saarbrücken

- A-1180 Vienna (from 1894)

Semperweg in

- CH-8910 Affoltern am Albis

Sempersteig in

- CH-8000 Zurich (Seilergraben towards ETH)

Semperplatz in

- 22303 Hamburg

literature

- Barbara von Orelli-Messerli: Gottfried Semper (1803–1879). The designs for decorative art. (= Studies on the international history of architecture and art , Volume 80.) Imhof, Petersberg 2010, ISBN 978-3-86568-310-6 . (Dissertation, University of Zurich, 2010)

- Christoph Hölz: Semper, Gottfried. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 24, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-428-11205-0 , pp. 243-247 ( digitized version ).

- Henrik Karge (Ed.): Gottfried Semper. Dresden and Europe. The modern renaissance of the arts. Files from the International Colloquium of the Technical University of Dresden on the occasion of Gottfried Semper's 200th birthday. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich / Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-422-06606-9 .

- Peter Noever (Ed.): Gottfried Semper. The Ideal Museum. Practical art in metals and hard materials (= Studies des MAK , Volume 8.) Schlebrügge, Vienna 2007, ISBN 978-3-85160-085-8 .

- Michael Gnehm: Silent poetry. Architecture and language with Gottfried Semper (= studies and texts on the history of architectural theory ) gta-Verlag, Zurich 2004, ISBN 3-85676-127-6 .

- Winfried Nerdinger , Werner Oechslin : Gottfried Semper 1803–1879. Architecture and science. gta-Verlag, Zurich 2003, ISBN 3-7913-2885-9 .

- Rainer G. Richter: From Hamburg to Rome and a lot in between. Gottfried Semper (1803–1879) on his 200th birthday. Architecture and ceramics in the historicism of Semper. In: Keramos , issue 182 (2003).

- Harry Francis Mallgrave: Gottfried Semper. A 19th century architect. gta-Verlag, Zurich 2001, ISBN 3-85676-104-7 .

- Wolfgang Hänsch : Gottfried Semper and the third Semperoper. 1978.

- Dirk Hempel : Literary Associations in Dresden. Cultural practice and political orientation of the bourgeoisie in the 19th century. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2008, ISBN 978-3-484-35116-5 .

- Ulrich Schulte-Wülwer: Gottfried Semper. In: Ulrich Schulte-Wülwer: Longing for Arcadia. Schleswig-Holstein artists in Italy. Heide 2009, pp. 198-204.

- Sonja Hildebrand: Gottfried Semper. Architect and revolutionary , Darmstadt: wbg Theiss 2020, ISBN 9783806241259 .

- Peter Wegmann: Gottfried Semper and the Winterthur town house. Semper's architecture in the mirror of his art theory . Winterthur City Library, Winterthur 1985, ISBN 978-3-908-05001-8

Web links

- Gottfried Semper. on: stadtwikidd.de , accessed on February 27, 2016 .

- Entry on Gottfried Semper in the Austria Forum (in the AEIOU Austria Lexicon )

- Martin Fröhlich: Semper, Gottfried. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Gottfried Semper. In: arch INFORM .

- Literature by and about Gottfried Semper in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Gottfried Semper in the German Digital Library

- Digital copies of works by and about Semper from the ETH Library

- Gottfried Semper in the ETH Library's “Portrait of the Month”

- Gottfried Semper at arthistoricum.net - context of the history of science and digitized works in the themed portal "History of Art History"

- Gottfried Semper - Feuilleton on his 100th birthday in the Innsbrucker Nachrichten

- Information about the tomb

Individual references and comments

- ↑ a b c d Wolf Stadler ao: Lexicon of Art 11th Sem - Tot. Karl Müller Verlag, Erlangen 1994, ISBN 3-86070-452-4 , p. 6.

- ↑ Mallgrave, Harry Francis: Gottfried Semper. Architect of the Nineteenth Century . Yale University Press, New Haven & London 1996, pp. 11 .

- ↑ Martin Fröhlich: Gottfried Semper. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ Heidrun Laudel : Gottfried Semper. Biographical overview. In: Winfried Nerdinger, Werner Oechslin (ed.): Gottfried Semper 1803–1879. Architecture and science. Munich / Zurich 2003, ISBN 3-7913-2885-9 .

- ↑ Eduard Alberti, p. 387.

- ↑ see entry by Semper in the Neue Deutsche Biographie (2010)

- ↑ Gottfried Semper (1803 to 1879) digitized version

- ↑ a b c Winfried Nerdinger, Werner Oechslin: Gottfried Semper 1803–1879. Architecture and science. Zurich 2003, ISBN 3-7913-2885-9 .

- ↑ a b c d Wolfgang Hänsch: History and reconstruction of the Dresden State Opera. Stuttgart 1986.

- ↑ From 1914 public café in Donners Park damaged by bombs in 1942 , demolished after dilapidation.

- ↑ The Monday Society was a debating club of witty people. Ferdinand Hiller founded it in 1845. That is why they were first called "Hiller-Kränzchen".

- ↑ The Albina was founded in 1828 as a “gentlemen's society of the educated estates” and was in the tradition of the Dresden Liederkreis.

- ↑ Dirk Hempel: Literary Associations in Dresden. Niemeyer-Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-484-35116-5 .

- ↑ Fritz Schumacher: How the Hamburg work of art came into being after the great fire. Hans Christians Verlag 1917, reissued in 1969, without ISBN, pages 24–28.

- ↑ a b c Hermann Sturm: Everyday Life & Cult. Gottfried Semper, Richard Wagner, Friedrich Theodor Vischer, Gottfried Keller. Basel 2003.

- ↑ Monica Bussmann: How Gottfried Semper became Swiss. In: ETHeritage. Highlights from the archives and collections of ETH Zurich. ETH Library, September 2, 2016, accessed on December 19, 2020 .

- ↑ Alphons Lhotsky: The building history of the museums and the new castle. Vienna 1941, p. 36.

- ↑ Allgemeine Bauzeitung , year 1844, pp. 5–9.

- ↑ Manfred Semper. Hasenauer and Semper. In: Allgemeine Bauzeitung. Year 1894, p. 59 ff.

- ↑ Margaret Gottfried: Das Wiener Kaiserforum. Vienna 2001.

- ^ The architect , born in 1895, p. 21f.

- ↑ The Order Pour le Mérite for Sciences and Arts. The Members of the Order, Volume I (1842–1881). Gebr. Mann, Berlin 1975, p. 336.

- ↑ knerger.de: The grave of Gottfried Semper

- ↑ Wolf Stadler et al .: Lexicon of Art 11th Sem - Tot. Karl Müller Verlag, Erlangen 1994, ISBN 3-86070-452-4 , pp. 6-7.

- ^ Terhi Kristiina Kuusisto: Textile in Architecture. Master's thesis, Tampere University of Technology, first introductory sentence.

-

↑ G. Semper: The four elements of architecture. (PDF 15.9 MB). Braunschweig 1851;

The Four Elements of Architecture and other writings. Cambridge University Press, England 1989. - ↑ See Andreas Dorschel : Commentary on Gottfried Semper, "Science, Industry and Art" (1852). In: Klaus Thomas Edelmann and Gerrit Terstiege (eds.): Thinking about design - basic texts on design and architecture. Birkhäuser, Basel, Boston, Berlin 2010, p. 106.

- ↑ In Affoltern am Albis a school house and a street were named after him. Semper designed the church tower near the school house.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Semper, Gottfried |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German architect and art theorist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 29, 1803 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Hamburg |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 15, 1879 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Rome , Italy |