Hamburg fire

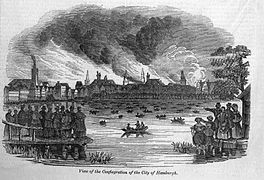

The Hamburg fire was a major city fire in Hamburg that destroyed large parts of the old town between May 5 and May 8, 1842 . In connection with the history of Hamburg, there is often only talk of the Great Fire . The fire was still visible from a distance of over 50 kilometers.

course

The fire broke out on May 5, 1842 at around one o'clock in the morning in house number 44 in Deichstrasse on Nikolaifleet near the cigar maker Eduard Cohen, according to other sources in house number 42. The exact cause of the fire remained unclear. It was quickly noticed by the night watchmen , but the syringe men who had rushed up were unable to put out the fire or prevent it from spreading to other houses. Due to the previous drought and persistent winds, it spread quickly. At times the fire even threatened to spread to the area on the other, eastern bank of the Nikolaifleet, the Cremon , but the smaller fires that arose there were suffocated in time. The fire in the Nikolaiviertel spread mainly to the north and west. Considerations of hindering the expansion by blasting were initially rejected.

On the morning of May 5th, Ascension Day in 1842, a considerable part of the Nikolaiviertel was already in flames. The main morning service was held in the Nikolaikirche , and another, final service was held at noon. Around 4 p.m. the tower caught fire and could not be saved despite great efforts. According to stories, the chimes sounded one last time due to the effects of the heat, then the tower collapsed and set the nave on fire.

Towards evening the flames threatened the old town hall , which stood northeast of the Nikolaikirche on the Trostbrücke on the square where the house of the Patriotic Society is today. After a large part of the files had meanwhile been brought to safety, it was decided to blow up the town hall, but the demolition was only incomplete, so that the flames found sufficient food in the rubble and could spread over the aisle.

During the course of May 6th, the fire migrated north and hit the area where the stock exchange and town hall complex is located today . The new exchange, which had only been moved into in December 1841, threatened to enter. Although the young building was temporarily surrounded by flames on all four sides, it was saved. In the evening the fire touched the goose market ; however, further expansion to the west could be stopped with the help of explosions.

It then spread to the east and north. On May 7th, despite desperate rescue attempts, the Petrikirche burned down, as did the Gertrudenkapelle , which was not rebuilt; the area east of it, including the Jacobikirche , was spared. The inner Alster and Glockengießerwall finally stopped the fire from spreading, and on May 8 the last house on Kurz Mühren street burned down . The extension of the Kurzen Mühren to the Ballindamm is therefore called the end of fire today . (The Brandstwiete in the southern old town, on the other hand, has nothing to do with the Great Fire, but is derived from the Hamburg citizen Hein Brand , whose arrest in 1410 led to the uprising of the Hamburg citizens and to the first Hamburg constitution.)

In the course of time, syringes (fire brigades) from cities in the near and distant neighborhood were called in, including from Altona , Uetersen , Wedel , Wandsbek , Geesthacht , Lauenburg , Lübeck , Stade and Kiel .

At the Zollenbrücke

Illustration for “Roland and Elisabeth” by Elise Averdieck

consequences

The great fire devastated more than a quarter of the then urban area. 51 people were killed, the number of homeless people was estimated at 20,000, the number of destroyed houses at around 1,700 in 41 streets. 102 granaries were destroyed, as were three churches, including the main churches of St. Nicolai and St. Petri, the town hall, the bank, the archive and the Commercium with the old stock exchange.

For years the cityscape was characterized by the destroyed areas and the makeshift apartments built on them, which were supposed to alleviate the homelessness of citizens and businesses.

As early as May 6th, an aid association for the victims of the fire had been set up in the house of the businessman August Abendroth , whose members joined a public support agency by resolution of the Senate on May 11th. At the same time, the extensive destruction in the old town gave the opportunity to comprehensively redesign the inner city area and modernize the infrastructure. The planning for this was also tackled in May 1842 under the leadership of the English engineer William Lindley , before the clean-up work began on May 26th. The Hamburg architect Alexis de Chateauneuf was significantly involved in the renewal of the cityscape , and suggestions by the architect Gottfried Semper were also incorporated into the joint effort. The area around the Kleine Alster , where a new city center was created, changed particularly radically . Klosterstraßenfleet and Gerberstraßenfleet were filled in, the small Alster was brought into its current rectangular shape and the space for the town hall and town hall market was prepared, even if it was 44 years before the laying of the foundation stone for today's Hamburg town hall and a further eleven years until its opening.

Typical of the buildings that arose after the great fire were classicist forms and borrowings from Italian cities. The round arch style , which determines the appearance of numerous buildings such as the post office or the Niemitz pharmacy on Georgsplatz, was decisive . This after-fire architecture can still be seen today, for example, in the Alsterarkaden or the post office building by the architect Alexis de Chateauneuf , but overall only a few examples have survived.

In order to support the construction planning, to pass resolutions about the necessary funds, but also to improve the fire fighting and the inner-city water supply, as well as the reform of the fire fund, the citizens decided on June 16, at the request of the Senate, to set up an extraordinary council and citizen deputation for Reconstruction of the city, which should include five members of the Senate and fourteen citizens. That included

- Senate Syndicus Wilhelm Amsinck ,

- Senate Syndicate Edward Banks ,

- Senator Andreas Friedrich Spalding ,

- Senator Martin Johann Jenisch the Younger ,

- Senator Heinrich Kellinghusen ,

- Senior elder Johann Jürgen Nicolaus Albrecht ,

- from the college of the 60s Anton Dietrich Schröder ,

- from the finance department Friedrich Hinrich Suse and Christian Wilhelm Köhler as well

- Eduard Johns and Hermann Baumeister as deputies from the parish of St. Petri,

- Christian Jacob Johns and Georg Heinrich Kaemmerer from the parish of St. Nicolai,

- Johannes Amsinck and Heinrich Geffcken from the parish of St. Katharinen,

- Carl Ludwig Daniel Meister and Franz Georg Stammann from the parish of St. Jacobi as well

- Johann Friedrich Anton Wüppermann and Theodor Dill from the parish of St. Michaelis.

The inner-city water supply through pumping stations was largely destroyed and was not restored; instead, a waterworks was built in Rothenburgsort . The water mills on the Alster were also destroyed . Although it became clear that water mills were technically outdated, a new city water mill was built on Poststrasse , which was fed by an underground line from the Inner Alster.

The water level of the Alster could be reduced, which made the areas Uhlenhorst and Harvestehude available for settlement. This was accompanied by the dismantling of the ramparts and finally the abolition of the gate barrier in 1860.

Underground canals to the Elbe were dug for urban drainage . In addition, gas lighting was started to replace the old oil lamps.

Of the three churches that were destroyed, only two were rebuilt. The Petrikirche received roughly its old appearance and has been preserved in this form to this day; Instead of the old Nikolaikirche, one of the most important neo-Gothic church buildings in Europe was built. For a long time, the new tower was the tallest building in Hamburg. The new Nikolaikirche was badly damaged in the Second World War , and today only the tower and some remains of the wall remain.

For the Hamburg area, the fire was primarily of economic importance. The brickworks in the marshland on the Elbe and Oste , for example, flourished in the period that followed due to the large demand for building materials.

An important event in Hamburg's history had to be postponed because of the great fire, namely the opening of the first Hamburg railway line . This led to Bergedorf and was to be opened to traffic on May 7, 1842. Instead of guests of honor, the first trains carried refugees from the burning city - regular operations did not start until May 17th without celebrations.

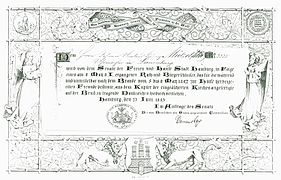

On May 8th, 1843, the first anniversary of the end of the fire, it was decided at the request of an honorable council to the hereditary citizenry , with a commission, to offer the most heartfelt thanks for the various assistance and the solemn and public presentation of commemorative coins and medals made of bronze or copper of the melted bells. In 1843, Johann Smidt , the mayor of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen , the Upper President of the city of Altona and the Upper President of the Prussian Province of Saxony in Magdeburg were granted honorary citizenship of Hamburg.

Compensation from the fire insurer

The Hamburger Feuerkasse , which compensated all the building owners affected, stated that 20 percent of the building stock had been destroyed. She had to take out loans that were not fully paid off until 40 years later. The Aachener Feuerversicherungs-Gesellschaft, a forerunner of today's AachenMünchener Versicherung, paid compensation of 320,000 thalers; the main damaged fire insurance bank, Gothaer Feuer , paid a total of 1.4 million thalers as compensation. The total property damage was estimated at more than 140 million marks. The Hamburger Feuerkasse, a public building insurance company, had to compensate 45 million marks for a total insurance sum of 223 million marks. For this purpose, a loan in the amount of 48 million marks was issued, the repayment of which was made in part from tax revenues and was not completed until 1888. Private fire insurance companies could not choose this entirely logical procedure. For example, the Association of Hamburg Residents , founded in 1795 at the instigation of Georg Ehlert Bieber , had to file for insolvency for insurance against the risk of fire , because it only had reserves of 500,000 marks for a claim for damages of more than 18 million marks. Two Hamburg fire insurance companies suffered the same fate: the Second Hamburg Insurance Company with 1.6 million marks and the Fifth Hamburg Insurance Company with 4.3 million marks. Another insurance company, the Patriotic Assekuranz-Compagnie , doubled its share capital and was able to compensate for the damage totaling 1.5 million marks. The fire insurance company Altona, which was only slightly affected, was able to fully meet the requirements. Most of the supraregional, partly foreign, fire insurers paid their obligations very quickly and in full. These included two French, three or four English and four German insurers (Aachen and Münchener, Colonia , Leipziger and Gothaer). The London-based Phoenix Assurance Company , founded in 1782, published in a commemorative publication of the tabloid Daily Herald in 1960 a loss amount of 250,000 pounds sterling - that corresponded to about 1.7 million thalers, the insurance company Sun named in the same magazine a sum of 117,000 pounds, or 800,000 Thalers. In a commemorative publication published in 1924, the London Alliance named 40,000 pounds - 170,000 thalers. The Royal Liverpool suffered the greatest loss of the British insurers, the loss of which was even greater than that of the Sun. The claims of the German insurers amounted to 1.4 million thalers for Gothaer, 320,000 thalers for Aachener and Münchener, 114,000 thalers for Colonia and 67,000 thalers for Leipziger. The Aachen and Munich director Brüggemann personally ensured that all damages were paid within two weeks, Colonia did this within five weeks and Gothaer within three months.

reception

Heinrich Heine , who made a trip to Germany in 1843, also visited Hamburg, which was again being built. The Hamburg fire is in the 21st chapter (Caput XXI) of his verse epic Germany. A winter fairy tale entered.

literature

- David Klemm: Hamburg burns: For the visual representation of a disaster of the century. In: Entfesselte Natur: Das Bild der Katastrophe seit 1600 , edited by Markus Bertsch and Jörg Trempler, Michael Imhof Verlag, Petersberg 2018, pp. 80–89, ISBN 978-3-7319-0705-3 .

Contemporary representations

1842

- NN: Hamburgs horror days, in: Der Freischütz , Volume 18, 1842, pp. 290-299, digitized , ZDB -ID 2645241-8

- JA Michaelis: Hamburg's fire accident abroad's undying fame. A detailed description of the terrible conflagration that hit Hamburg so hard from May 5th to 8th, 1842, together with its consequences. Hamburg, At the author's expense, 1842, digitized

1843

- Karl Heinrich Schleiden : Attempt of a history of the great fire in Hamburg from May 5 to 8, 1842 , Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1843, digitized

- Ludolf Wienbarg : Hamburg and its fire days. A historical-critical contribution. Kittler, Hamburg 1843.

1844

- Friedrich Clemens Gerke : Hamburg's memorial book, a chronicle of its fates and events from the origin of the city to the last conflagration and rebuilding , BS Berendsohn, Hamburg 1844, p. 775ff., Digitalized

Fiction

- Elise Averdieck : Roland and Elisabeth (= children's life. Part 2). Kittler, Hamburg 1851 (207th thousand of the total edition. Köhler, Hamburg 1962), stories about the Hamburg fire for children from 6 to 10.

- Elise Averdieck: The Hamburg fire. 1842. Saucke, Hamburg 1993.

- Arne Buggenthin: 1842. The great fire of Hamburg . Acabus-Verlag, Hamburg 2019.

- Edgar Maass : The great fire. Novel. Propylaen-Verlag, Berlin 1939 (from Schröder, Hamburg 1950).

- Carl Reinhardt : The fifth of May. A picture of life from the Lower Elbe , 4 volumes, Wigand, Leipzig 1866–1868, volume 1 digitized , volume 2 digitized , volume 3 digitalized and volume 4 digitalized ; various new editions, some shortened, e.g. E.g .: 76.-80. Thousand. Revised and with an afterword by Harald Busch . Christians u. a., Hamburg 1989, ISBN 3-7672-0498-3 ).

- Paul Schurek : The Hamburg fire. Narrative. Glogau, Hamburg 1922 (ibid. 1949).

Web links

Remarks

- ^ Carl Friedrich Hermann Klenze : The Hamburg fire and Uetersen's help , part 1–3 (1842). Images on Wikimedia Commons : 1 2 3

- ↑ 170 years ago: The great Hamburg fire of 1842. Hamburger Feuerwehr-Historiker e. V. 2012 (PDF; 449 kB)

- ^ Hamburg address book 1841, directory of persons and companies , accessed October 13, 2016.

- ^ Hamburg address book 1841, street directory. Retrieved October 13, 2016.

- ↑ Save the Deichstrasse e. V. ( Memento from July 16, 2012 in the Internet Archive ), www.deichstrassehamburg.de, accessed on July 6, 2011.

- ^ Matthias Gretzschel: The first photo of Hamburg. Hamburger Abendblatt, December 24, 2002, accessed on March 29, 2017 .

- ^ Otto Christian Gaedechens : Hamburg coins and medals . JA Meissner, Hamburg 1850, p. 119 ff.

- ↑ The amounts of damage given in the literature are difficult to compare due to different currency information and conversion methods.

- ↑ Germany. A winter fairy tale by Heinrich Heine - text in the Gutenberg project. Retrieved July 14, 2020 .