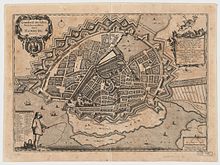

Hamburg ramparts

The Hamburg ramparts were fortifications that were built around Hamburg from 1616 to 1625 under the direction of Johan van Valckenburgh . Between 1679 and 1682, the so-called “New Plant” to protect the eastern suburb of St. Georg and the Sternschanze in the north-west were added. After the end of the French occupation in 1814, the fortress structures were demolished and ramparts and ditches were converted into green spaces . While the eastern part later had to give way to the construction of the Hamburger Kunsthalle and Hamburg Central Station , the western section between Dammtor and Stintfang has been preserved as part of the Planten un Blomen park and the old Elbpark . The former Wallring is also clearly recognizable by the streets around the city center ( Ring 1 ).

prehistory

Since the 13th century, Hamburg was surrounded by a city wall that roughly enclosed the area of what is now the Hamburg-Altstadt district . East of the city there was an upstream Landwehr since the 14th century , which was supposed to protect the apron between the Hammer Baum (at today 's Burgstraße underground station ) and the Kuhmühle from intruders.

From 1475, the city wall in the area of the Alster lowlands was supplemented by a first wall ( Alter Wall ). In the middle of the 16th century, the entire (old) city was surrounded by the so-called New Wall , which already had several roundabouts . The street Neuer Wall still marks the course of this wall in the west of the old town. However, these fortifications were already out of date when they were built and limited the growth of the emerging city.

Due to the ongoing conflict with neighboring Altona , which then belonged to the Kingdom of Denmark , a more massive fortification was necessary. When the Danish King Christian IV founded the Glückstadt naval port in 1616 , the Hamburg residents commissioned the Dutch fortress builder Johan van Valckenburgh to build new fortifications.

Around a quarter of Hamburg's income had to be spent on building the ramparts for ten years. In 1624 the complex was essentially finished. Fortifications made of masonry would have cost many times over, and the investment in the ramparts quickly paid off for the city. During the Thirty Years' War Hamburg was one of the few German cities that remained unscathed. Because of its massive fortifications, not a single attack was made on the city during this war, so it was considered a safe place.

construction

The new fortifications were not only intended to enclose the previous urban area, but by including the Geest ridge to the west (" Hamburger Berg "), they were intended to prevent the lower town from being shot at with cannons from there. The chosen semicircle with a radius of around 1.2 kilometers around the Nikolaikirche also offered enough space for the necessary expansion of the city, today's Neustadt .

In order to be able to build as closed a fortress ring as possible around the city, an additional dam was raised, which from now on separated the Alster , which had been dammed up for a long time, into the Outer and Inner Alster (in place of today's Lombard Bridge ). In the south and east of the city, the existing wall was integrated into the new system and expanded. Several roundels were converted into bastions .

The fortifications were built from earth based on the Dutch model and surrounded by a wide moat. Ramparts and bastions were covered with turf and provided with pointed wooden posts, which should make it difficult to use scaling ladders to overcome the ramparts. The Hamburg population was obliged to participate in the construction.

Bastions and ravelins

The new wall ring was provided with a total of 22 bastions , 21 of which had a pentagonal floor plan, while one of the smaller bastions protruded as a triangle from the ramparts. All bastions were named after the councilors who were in office in the 17th century . From the western port entrance these were clockwise:

| Johannis | east of the Landungsbrücken (street Johannisbollwerk ), at that time the western boundary of the harbor entrance |

| Albertus | at the smelt catch |

| Casparus | near the Bismarck monument |

| Henricus | near the Museum of Hamburg History |

| Eberhardus | near the artificial ice rink Wallanlagen |

| Joachimus | near the Laeiszhalle on Johannes-Brahms-Platz |

| Ulricus | near the Hamburg pre-trial detention center |

| Rudolphus | In Planten un Blomen at the Stephansplatz underground station , parts of the bastion and the fortification moat are still clearly visible |

| Peter | near the Dammtor train station |

| Diedericus | at the western beginning of the Lombard Bridge |

| David | on the wall that separated the Outer and Inner Alster |

| Ferdinandus | upstream bastion on the left bank of the Alster, at the gallery of the present , namesake for the later "Ferdinandstor" |

| Vincent | at the old building of the Hamburger Kunsthalle |

| Jerome | near the Hamburg Central Station |

| Sebastian | Corner of Steinstraße / Steintorwall |

| Bartholdus | near the Deichtorhallen at Deichtorplatz |

| Ericus | Ericus at the top of the new Spiegel publishing house |

| Nicolaus | today Brooktorkai / Osakaallee |

| Gerhardus | today Sandtorkai / Sandtorpark |

| Ditmarus | at today's Sandtorkai |

| Hermannus | at today's Sandtorkai |

| Georgius | in front of the island of Kehrwieder , today Kehrwiederspitze, at that time the eastern boundary of the port entrance |

There were also 11 ravelins with a triangular floor plan, which were supposed to protect the trench sections between the bastions. The 15 bastions in the west and east of the complex were made in full size, while the bastions on the south side facing Grasbrook and the Elbe were made in a smaller form.

To the west of the city, a so-called horn factory was built on the banks of the Elbe in today's St. Pauli district to protect the port and the Albertus and Casparus bastions . This advanced fortification was supposed to keep enemy troops at a distance from the actual fortress. The "Sternschanze" , which was later moved to the northwest, was supposed to fulfill the same purpose (see section: Extension).

The fortifications were armed with almost 300 cannons . The ramparts were completed by a glacis , an enemy-sloping embankment around the city. The street names "Alsterglacis", "Glacischaussee" and "Holstenglacis" remind of this.

City gates

After the medieval city wall of Hamburg still had up to ten city gates , their number was reduced to six in the course of the fortress construction: Millerntor and Dammtor broke through the wall on the west and north side, Steintor and Deichtor on the east and south-east side; Sandtor and Brooktor led south to the Elbe and Grasbrook respectively . This condition lasted around 200 years. Only after the French era , in the first half of the 19th century, were further openings added for the growing traffic (port gate at the Landungsbrücken , Holstentor at Sievekingplatz , Ferdinandstor and Klostertor ). The gate lock replaced the gate closure on September 13, 1798 and was lifted on December 31, 1860 .

Extension: "New Plant" and Sternschanze

A rampart of the same type, the so-called New Plant , was built between 1679 and 1682 to protect the suburb of St. Georg . The area, parallel to the (today's) streets Sechslingspforte and Wallstraße, was later used for the St. Georg General Hospital and the S-Bahn and U-Bahn tracks at the Berliner Tor . The new work was interrupted by two gates on the highways to Lübeck and Berlin: At the Lübeck Gate today still remembers the street Lübeckertordamm and to the Berliner Tor the Berlinertordamm . Later, in Alster near another passage addition, a fee of for its use six pence (equivalent to half a shilling was payable). The Sechslingspforte street in Hohenfelde is a reminder of this.

At the same time as the New Plant, an upstream Sternschanze was built in the north-west of the city , which was intended to keep enemies away from the actual Wallring and was connected to the city by a trench. It later gave its name to the Sternschanzenpark , the underground and S-Bahn station there and, in 2008, the district of the same name .

A surge in the protection of the fortifications and the transformation of the ramparts into green spaces

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Hamburg assumed a special role in German economic history by protecting the ramparts and developed into one of the most important European trading cities. Due to its fortifications, numerous refugees came to the city during the Thirty Years War , which greatly increased the population. In the middle of the 17th century, Hamburg emerged from the war as the wealthiest and most populous city in Germany.

The sharp increase in population, however, increasingly led to cramped space and living conditions within the ramparts. The step-by-step introduction of the gate lock in Hamburg from 1798 onwards, which made admission possible after the gate closed against payment of a blocking fee, made things easier, also in traffic with the growing neighboring towns .

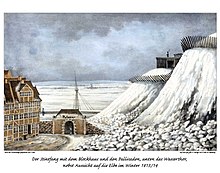

The long phase of the economic boom was only interrupted at the beginning of the 19th century. At that time, the ramparts were already very much out of date. In order not to get involved in armed events, it was decided in 1804 to convert the ramparts into a park. The fortification was no longer an obstacle for the French who took Hamburg in 1806. However, the French began to rebuild Hamburg into a fortress and to restore the ramparts on the orders of their Marshal Davout . The citizens of Hamburg were obliged to do forced labor.

The French occupation ended in 1814 and Hamburg joined the German Confederation the following year . Due to the changed political situation and taking into account the expansion of the city, the ramparts were removed from 1820 to 1837 and converted into green areas under the direction of Isaak Altmann . The old city gates were exchanged for new gate systems, as the gate lock, although long felt to be out of date, was not lifted until 1860.

Altmann's green spaces gained exemplary character throughout Germany during their time. However, they suffered serious losses again from the 1840s (construction of the Hamburg-Bergedorfer Bahn ). In particular, the construction of Hamburg's main train station (1898–1906) with the associated track systems as well as the construction of public buildings such as the art gallery, the Reich Postal Administration and the General Customs Directorate had a destructive effect on the eastern part of the green corridor in the early days . Only in the west of the city center did it initially remain unchanged.

Already during the Second World War , especially immediately after the capitulation in 1945, the very deep trenches of the ramparts were used to deposit rubble from the neighboring parts of the city center. As a result, the terrain is considerably flattened.

While large parts of the city moat were still preserved around 1890, this disappeared due to the deposition of rubble and the necessary redesign, except for a small piece in the Old Botanical Garden on Stephansplatz . Even behind the wooden dam in St. Georg was a small piece of moat, the "Philosophenteich", which now only reminds of the footpath parallel to the railway line, once called the Philosophenweg, until the City S-Bahn was built .

Today's image of the (western) ramparts is mainly due to the redesign for the international horticultural exhibitions in 1963 and 1973.

Wall systems today

View from Stephansplatz over the Old Botanical Garden to the Heinrich Hertz Tower

Today the former ramparts are divided into the large ramparts , the small ramparts and the old botanical garden . On the occasion of the International Horticultural Exhibition in 1963, these parts of the park were brought together by road bridges and an (initially provisional) road roof to form a continuous park. The ramparts between Millerntor and Dammtor have officially been named Planten un Blomen since 1986 . The section between Millerntor and Stintfang , on the other hand, is called the Alter Elbpark .

Only the Rudolphusbastion at the Stephansplatz underground station has been partially preserved.

The Bismarck monument was erected on the Casparus bastion in 1906 .

Numerous street names are reminiscent of the earlier ramparts, such as Johannisbollwerk, Holstenwall , Dammtor , Dammtorstraße , Glockengießerwall , Lange Mühren, Kurz Mühren, Klosterwall, Hühnerposten , Millerntor , Klostertor , Deichtorplatz , Alsterglacis, Holstenglacis or Glacischaussee. Even after Jan van Valckenborgh one was bridge over a remaining part of the moat in the park Planten un Blomen named.

Between the Dammtor station and south of the main station to the Deichtorhallen , the long-distance railway tracks now use the site of the old fortifications. The connecting line that connected the main train station with the Altona train station was also built on the site of the former ramparts. The road tunnel to relieve traffic at the main train station is called the Wallring tunnel .

literature

- Marion Bendzko-Ciecior: The Hamburg ramparts. An example of the development of the park green with changed urban and green planning objectives. Hamburg 1989.

- Karl-Klaus Weber: Hamburg, the impregnable city. Johan van Valckenburgh's fortifications . In: The war at the gates. Hamburg in the Thirty Years War 1618–1648. Hamburg University Press 2000, pp. 77-100.

- Karl-Klaus Weber: Johan van Valckenburgh. The work of the Dutch fortress builder in Germany 1609–1625. Böhlau, Cologne 1995, ISBN 3-412-04495-4 , pp. 40-54.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Cipriano Francisco Gaedechens in “Hamburg. Historical, topographical and building history communications ”, Verlag O. Meissner, Hamburg 1868.

- ↑ Isabelle Pantel: The Hamburg neutrality in the seven years war . Publications of the Hamburg Working Group for Regional History (HAR), LIT-Verlag, Berlin / Münster 2011, ISBN 978-3-643-11542-3 , p. 81 ff.

- ↑ Monument topography Germany, Hamburg inventory, Eimsbüttel and Hoheluft-West, Christians Verlag, Hamburg 1996.

- ^ Percy Ernst Schramm: Hamburg. A special case in the history of Germany. Hamburg 1964, p. 23.

- ↑ Maja Kolze: City of God and "Cities Queen". Hamburg in Poems from the 16th to the 18th Century , 2011, p. 10.

- ↑ In 1650 Hamburg had 60,000 inhabitants, 1714 Cologne 42,000, 1750 Nuremberg 30,000, 1662 Lübeck 26,597, 1650 Bremen 25,000, 1665 Augsburg 25,000, 1700 Munich 24,000, 1700 Frankfurt 23,000, 1648 Leipzig 14,000, 1648 Berlin 6,000 and 1663 Düsseldorf 4,085 - cf. . Category: Population development (Germany) by municipality ; 1650 Vienna 47.500 - Andreas Weigl: "Demographic change and modernization in Vienna, 1707 to 1991" Archive link ( Memento of the original from September 24, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Gabriele Hoffmann: The ice fortress. Hamburg in the cold grip of Napoleon . Piper, Munich 2012, ISBN 3-492-30183-5 .