Hamburg citizen military

The Hamburg citizen military, also called "Hanseatic Citizens Guard", was a civil defense formation of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg founded in 1814 and existing until 1868 , which was made up of conscripted citizens and townspeople.

Citizen Guard, Hanseatic Legion, Hamburg Garrison and Infantry Regiment Hamburg

As far as there was temporal overlap, the citizen military existed alongside other military formations in Hamburg. In contrast to the standing Hamburg garrison, its members were not barracked . The reasons for the parallel existence of both troops are of different nature. The Hanseat rejected the one to regularly officer corps forming needle (cf.. " Hanseat and nobility ") and hated at the same time the composite of uprooted lives largely team status. Hamburg needed these troops in order to be able to occupy and defend its fortifications sufficiently in the event of a crisis, but did not want to rely on them alone. The civil military as a second unit in the event of war, especially since the members had to pay for their own costs, was cheaper than an otherwise necessary increase in the garrison. Since Hamburg had practically had military sovereignty since the end of the 13th century, the purposes of arming the people elsewhere played no role, such as the intention not to give the princes any means of pursuing claims to power in foreign policy. But the people of Hamburg also valued the fact that the citizen's military was a force that the Senate could not easily use against the citizens.

The citizen militia did not follow the tradition of the “Bürgerwache” (civic guard) of Hamburg, which, due to its miserable condition, had a “generally recognized ridiculousness, shown in caricatures”. In contrast, the Hamburg citizen military received recognition for its good equipment, uniforms, training and leadership. In 1843 it took part in a concentration of the X Army Corps in the Lüneburg area, with the cavalry almost arousing the admiration of the assembled military.

If the officer corps of the later civil military was the domain of the merchants and upper-class citizens , the officers of the civil guard were “mainly from the middle and petty bourgeoisie.” In contrast to the civil guard, the civil military was an element of comprehensive armament, i.e. a militia . A vigilante guard, on the other hand, was primarily a unit that performed police tasks and served more to secure social conditions than to defend against external enemies. The civil guard existed until 1810 and was disbanded under the French occupation.

The " Hanseatic Legion " was a volunteer group founded by the interim liberator of Hamburg, Colonel Tettenborn (1778-1854), parallel to the forerunners of the citizen military, which was to go into the fight against Napoleon . Not least because of the Senate's (justified) fear of the returning French under the Russian flag, they fought not to give an excuse for retaliatory measures against the city and subsequently consisted not only of hamburgers but also of residents of Bremen and Lübeck .

When Hamburg joined the North German Confederation in 1867, Hamburg gave up its military sovereignty and initially had to take on two battalions of the Prussian Army . The Hamburg contingent to the armed forces of the German Confederation was dissolved and the men and officers of the Hamburg garrison (city military) were transferred to the new infantry regiment "Hamburg" (2nd Hanseatic) No. 76 .

In addition, the Hamburg citizen military was able to exist for another year before it was finally dissolved in 1868.

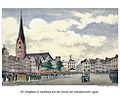

The other troops in Hamburg in the picture

history

Lineup

Already during the Napoleonic occupation operated u. a. David Christopher Mettlerkamp (1774–1850) and Friedrich Christoph Perthes (1772–1843) created a powerful force for the planned overthrow after Napoleon's defeat in Russia . The policy of the old Senate, which was aimed at neutrality, meant that Hamburg could only expect very limited outside help, as was shown by the successful siege of the city by Vandamme in May 1813. Mettlerkamp was subsequently commander of the "Hanseatic Citizens Guard", which, in contrast to the "Hanseatic Legion", which also took part in the war against France, was only to be used for the liberation of the Hanseatic cities.

She took part in the siege of Hamburg, which was occupied by Marshal Davout , and after his withdrawal rode into the liberated city at the head of the troops led by General Bennigsen .

During discussions as to whether the old vigilante guard should be revived or a citizen militarist should be created, the proponents of a mere vigilante guard referred to the impairment of employment opportunities through military service and turned against a stronger militarization of Hamburg. In contrast, the civil guard officers who had returned from the field, to whom the civil guard appeared to be a relic from the past, embodied the spirit of the times. Therefore, on June 3, 1814, Mettlerkamp received the order to reorganize the civil guard. In the competition between the civic militaries that dissolved after the war, the existing and competing civic guards and the returning Hanseatic Legion, it initially failed until the Senate created compulsory military service in Hamburg on September 10, 1814, according to which all citizens and residents as well as their sons from 20 to 45 years of age . Years of service were compulsory. The reform was promoted by the pathetic condition of the vigilante guard and its "generally recognized and caricatured ridiculousness".

The citizen militia drew its legitimacy from the experiences of the wars of freedom : “The Hamburg citizen militair is founded both in Hamburg's special constitution and in the general German armament that was restored in 1813.” The views on military service may also be very different “in the monarian and republican states , but nevertheless the free man's right to arms is and remains deeply rooted in German nature. "

The Hamburg fire of 1842

In addition to some unpleasant incidents, especially with the federal contingent, the citizen's military proved itself during the Hamburg fire of 1842. While the city's administrative bodies were weak, lacking in leadership and incompetent, many people marched through the city and plundered. Of course, where "the civil guards, (...) especially the officer corps , were at hand in sufficient strength, it was possible to drive the robbers into pairs with little energy, but at least with the naked weapon." It spoke for the authority of the officers and the willingness of the guardsmen that, in view of the utter confusion in the city and the failure of the political leadership, the civil military did not join the "general and headless race, rescue and escape of all residents of Hamburg".

The revolution of 1848/49

The civil military acted less happily during the revolution of 1848/49 . Disputes within the officer corps over the quality of the troop leadership finally ended in a duel between Colonel Stockfleth and Major Kessler, the battalion commander of the hunters. The question of how the civic military should fulfill its mandate, as well as the political tensions, carried over to the individual units of the civic military.

According to the civil military regulations of 1848, NCOs and officers were now to be elected by the men. This gave an advantage to those who, given their economic circumstances, were able to afford to eat and drink plentifully. The electoral law was therefore repealed at the end of 1849 after calm had returned.

When Prussian troops came from the theater of war in Schleswig-Holstein in August 1849 and were quartered in the city, the Gänsemarktwache was stormed by guards and tumulters. It was not until the next morning that parts of the civil military were able to end the tumult.

Otherwise, however, the civilian military fulfilled its regulatory function. In Hamburg, where more than three quarters of all residents were excluded from civil rights and, to an even greater extent, from any say in the matter, demonstrations of dissatisfaction were particularly prevalent in times of crisis. "Since the members of the civil military belonged to the privileged, they mostly fulfilled the city government's policy, which was determined by the interests of the large merchants."

The last reform from 1854

The last reform of the civil military took place in March 1854. The officers prevented a regulation according to which, in urgent cases, the police officer could have called up the civil service, as this would have put the civil service on an equal footing with the paid police corps. The task of national defense was also retained in order not to turn the civilian military into an auxiliary police force. In the case of joint operations by the citizenry and contingent, the Senate was now in command in order to avoid disputes over competence. The stipulation remained that anyone who went bankrupt was demoted to a simple guardsman . Business success or failure and advancement in the civil military remained closely linked.

Loss of meaning and dissolution

After 1849, however, the civil military lost its political importance, and its tasks were gradually restricted. Nor did it keep pace with military developments. Questions of etiquette and representation became more and more important. When Hamburg joined the North German Confederation in 1866 , the federal contingent was dissolved and replaced by the "Hamburg" (2nd Hanseatic) No. 76 infantry regiment . The civil military no longer fit into this military system. At the suggestion of the citizenry passed by a narrow majority, the Senate decided, despite a signature campaign that had collected over 14,000 signatures in ten days, to dissolve the citizen military "in which many bourgeois families had seen their pride", which took place on July 30, 1868. "With the Hamburg citizen military, the last testimony to the idea of a democratic, defense-only military constitution that was born in the wars of freedom disappeared." The IR 76 was originally set up on October 30, 1866 in Bromberg and took over on October 1, 1867 according to the Convention of June 27, 1867 Men and NCOs of the disbanded battalions of the federal contingents of Hamburg and Lübeck. With the formation of the North German Confederation, Hamburg had given up its military sovereignty.

Organizational structure

Seven battalions were formed in Hamburg : six infantry battalions of six companies each , a hunter battalion and a sniper company . There was also a battalion in the suburb of St. Georg and a battalion in the rural area. The company was 200 men in the infantry and 100 men in the hunters and snipers. The regulations also provided for the formation of an artillery and a cavalry corps . At the head of the civil military was a lieutenant colonel as chief , and from 1840 a colonel . The general staff, consisting of four majors and four adjutants , was subordinate to him . Each battalion was led by a major, and the company commanders had the rank of captain . In order to ensure continuity and professionalism, the chief of the civil military, the auditor , the drum and a tribe of artillerymen were paid .

The officers were elected - the chief of the citizen military from the Senate from a list of proposals from the citizen military commission, the majors and captains from the citizen military commission, and the lieutenants and first lieutenants from a commission made up of the chief of the citizen military, the battalion and the company commander. The civil military was thus largely isolated from external influences when selecting its officers and was able to develop a completely closed officer corps in the individual battalions . "The most respected citizens of the city gladly took over an officer position in the service that was so annoying at the time."

The service regulations stipulated: “The officers and NCOs must never forget that their subordinates are citizens and, apart from the service, are equal to them.” Nonetheless, the service regulations essentially dealt with penalties for violations of discipline, whereby in practice the majority of the conscripts should be disciplined by fines and imprisonment, while officers and non-commissioned officers were threatened with demotion and dishonorable dismissal.

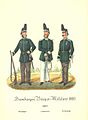

The troops in uniforms since 1853

The relationship between the citizen's military and the federal contingent

Tensions between the two very different military formations in one city were inevitable. The officers of the federal contingent valued the military qualities of the citizen military lower, while the officers of the citizen military felt superior because of their special status as armed citizens. This was even true of the individual guardsmen in relation to soldiers of the federal contingent, who lived in inhumane accommodations and were still subject to corporal punishment . The reputation of the federal contingent was poor among the population, as the soldiers were considered to be a kind of bodyguard for the Senate, while the civil military had a reputation for defending civil liberties. Since the soldiers were often more brutal and more likely to use firearms, the civil military gained a clear advantage among the population, especially in connection with the September unrest in 1830.

The civil military successfully opposed any form of subordination to the contingent early on. When, on the occasion of a parade on October 18, 1823, the city commander and chief of the garrison were supposed to lead the high command of both formations, because as a colonel he had a higher rank than the major in office as chief of the civil military, this appeared “to the officers of the civil military as a tremendous one Provocation. Placing them under the command of a professional soldier hurt their sense of class. ”The fact that the civilian military prevailed on this issue shows that“ the civilian military was also a factor in the domestic political game of forces. ”

The relationship only relaxed from 1835, when the application of conscription to the federal contingent also changed it from a mercenary force to a conscription force.

Significance and social structure of the citizen military

The citizen's military was an important factor in Hamburg. At times it played a role in politics that should not be underestimated. In particular through its self-image of being a guarantor of civil rights, it exerted a not inconsiderable influence on political decisions, especially since it was assigned important administrative tasks.

Unlike in the Prussian army , it was not membership of the military that made the individual part of the leading social class. In Hamburg the merchants were the leading group and they found themselves numerically strong in the officer corps and maintained their contacts in the officers' associations formed at battalion level. The officer drew his authority not from a certain class, but in a strictly bourgeois sense from his own performance, education and persuasiveness. The citizen officer's honor was indivisible. Since discipline was based on the personal integrity of the officer, no distinction was made between defamation by the officer in service and in private life. The duel was accepted in the civil military as a means of restoring honor. A corps spirit prevailed among the officers of the civil military that demanded the exclusion of dissenters of all kinds. Over time, the officers became the actual backbone of the civil guard. Their group consciousness, which they cultivated in their officers' clubs, is largely characterized by the fact that they adopted the concept of honor of the professional officers. Great emphasis was placed on creditworthiness. Those who went bankrupt lost their officer rank.

The leading group of long-distance trade merchants in Hamburg majored over the officer corps. If members of the lower and lower bourgeoisie wanted to improve their legal status in the city, they had to acquire citizenship. Membership in the citizen's military was a prerequisite for acquiring citizenship, as was the obligation to defend the city, which was part of the Hamburg citizens' oath . However, the cost of uniform and equipment was a significant expense. The uniform and equipment of the cavalry were particularly expensive. All metal parts of the uniform of the officers of the cavalry were gilded. The different levels of effort involved in uniforming at the same time created a barrier for the advancement of many members of the civil military and favored the social isolation of the volunteer corps. On the other hand, the officer's uniform of the Freikorps offered rich Hamburgers who did not belong to the older merchant families an opportunity to compete with them. During the debate in the citizenship about the abolition of the citizen military, MP Ferdinand Laeisz remarked that many of the supporters of the troops owed “the high position they occupy in society” to the citizen military.

In other respects, too, the Freikorps artillery, hunters and cavalry clearly distinguished themselves from the infantry. The Freikorps also decided who they wanted to accept. With the cavalry, the person to be admitted had to have an innocent reputation and be a "trained Reuter". He had to own a riding horse - rental horses and draft horses were forbidden - and contribute to the cost of equipping the trumpeters and maintaining their horses. "These statutes make it clear what [...] was really essential for being accepted into a volunteer corps for the fulfillment of the military task: the possession of a sufficient amount of money." Merchants, 112 of whom paid for “the very splendid uniform with the Ulanentschapka, the armament with dragons and two pistols” and the riding horse.

Members of the citizen military

Chiefs of the civil military

- Peter Kleudgen (1775–1825) 1815 to 1825

- Johann Andreas Prell (1774–1848) 1825 to 1831

- Johann Friedrich Anton Wüppermann (1790–1879) 1831 to 1835

- Carl Möring (1818–1900) 1835 to 1838

- Daniel Stockfleth (1794–1868) 1838 to 1848

- Albert Nicol (1799–1887) 1848 to 1868

- (on an interim basis until liquidation) Hinrich Jacob Burmester (1799–1876) 1868

cavalry

- Adolph Godeffroy (1814-1893), Rittmeister

- Carl Jauch (1828–1888), first lieutenant

- Moritz Jauch (1804–1876), First Lieutenant (husband of Auguste Jauch )

- Ernst Freiherr von Merck (1811–1863), captain and chief of the cavalry

Other units

- Carl Eduard Abendroth (1804–1885), major in the general staff

- Georg Heinrich Ballheimer (1796–1874), second major of the 6th Battalion

- Carl Theodor Bandmann 1852-1859, Major of the 4th Battalion

- Wilhelm Gossler (1811–1895), adjutant in the General Staff

- Nicolaus Ferdinand Haller (1805–1876), guardsman of the 7th Company of the 3rd Battalion

- Carl Philipp Kunhardt (1782–1854), captain of the 2nd battalion

- Georg Ferdinand Kunhardt (1824–1895), captain

- David Christopher Mettlerkamp (1774–1850), Lieutenant Colonel and Commandant

- Gustav Eduard Nolte (politician, 1812) , captain

- Ludovicus Piglhein (1814–1876) Captain of the 6th Company of the 6th Battalion

- Hermann Poelchau (1817–1912), captain in the 6th battalion

- Johann Christian Söhle (1801–1871), second major of the 3rd Battalion

- Johann Stahmer (1819–1896), captain

literature

- Ulrich Bauche : Farewell to the citizen's military. Supplement to the Hamburgensien folder Hamburger Leben, part tenth. Hamburg 1976.

- Ulrich Bauche: The Hamburg Citizens' Military 1868 , in Ulrich Bauche - Look closely, contributions to the history of society in Hamburg, Hamburg 2019, pp. 146–152, ISBN 978-3-96488-019-2

- L. Behrends: Costs of acquiring small citizenship rights by a non-Hamburg citizen and uniforming as a citizen guard (1844). In: Communications of the Association for Hamburg History. Hamburg 1912.

- Hans-Hermann Damann: Military affairs and civil arming of the free Hanseatic cities in the time of the German Confederation from 1815–1848. Dissertation. Hamburg 1958.

- Andreas Fahl: The Hamburg citizen military 1814-1868. Reimer, Berlin / Hamburg 1987, ISBN 3-496-00888-1 .

- Klaus Groth: Chronicle of the Hamburg location. Images from Hamburg's military past. Dassendorf 2010.

- FHW Rosmäsler: Hamburg's citizen armament, shown in five and thirty figures. Hamburg 1816.

- W. Schardius: Cheerful and serious memories from the years of service of a former staff officer of the Hamburg Citizens' Militair. Hamburg 1881.

- Franz Thiele: Hamburg citizen military 1848/49. Fateful years of an almost forgotten citizen group. Hamburg 1974, OCLC 248347919 .

See also

- Hanseatic Legion

- Bremen city military

- Lübeck Citizens Guard

- Lübeck military (1814–1867)

- Lübeck city military

- Infantry Regiment "Bremen" (1st Hanseatic) No. 75

- Infantry Regiment "Hamburg" (2nd Hanseatic) No. 76

- Infantry Regiment "Lübeck" (3rd Hanseatic) No. 162

Web links

- Klaus Groth, Chronicle of the Hamburg location (PDF; 49.4 MB) - Timeline of all military events in Hamburg and images from all centuries on Hamburg's military history, including images of all troops and branches of service

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f Ulrich Bauche, supplement to the Hamburgensien folder Hamburger Leben, part tenth. Hamburg 1976.

- ↑ on the civil guard: F. Voigt: Some messages about the former Hamburg civil guard. In: Communications from the Association for Hamburg History. 30th year. Hamburg 1912.

- ↑ a b Mayor Amandus Augustus Abendroth , quoted from Fahl: The Hamburg citizen military. 1987, p. 31.

- ^ Klaus Groth: Chronicle of the Hamburg location. Images from Hamburg's military past. Dassendorf 2010, p. 42.

- ↑ Hamburg Infantry Regiment (2nd Hanseatic) No. 76

- ( F ) Andreas Fahl: The Hamburg citizen military 1814–1868. Reimer, Berlin / Hamburg 1987, ISBN 3-496-00888-1 .

- ↑ p. 16.

- ↑ p. 9.

- ↑ p. 20.

- ↑ p. 24 with reference to Cypriano Francisco Gaedechens, The Hamburg military until 1811 and the Hanseatic Legion, Hamburg 1889.

- ↑ p. 25.

- ↑ p. 27.

- ↑ p. 28.

- ↑ p. 29.

- ↑ p. 30.

- ↑ p. 32.

- ↑ a b p. 53.

- ↑ a b p. 59.

- ↑ p. 83f.

- ↑ p. 66.

- ↑ p. 67.

- ↑ p. 68.

- ↑ p. 70f.

- ↑ p. 74 f.

- ↑ p. 77.

- ↑ p. 79.

- ↑ p. 81f.

- ↑ p. 82.

- ↑ p. 34.

- ↑ p. 35.

- ↑ p. 37.

- ↑ p. 45.

- ↑ a b p. 38.

- ↑ p. 167.

- ↑ p. 168.

- ↑ p. 169.

- ↑ p. 55.

- ↑ p. 57.

- ↑ p. 195f.

- ↑ p. 197.

- ↑ p. 188.

- ↑ a b p. 191.

- ↑ p. 287.

- ↑ p. 284.

- ↑ p. 212.

- ↑ p. 246.

- ↑ p. 260.

- ↑ p. 282.

- ↑ p. 283.

- ↑ a b p. 178.

- ↑ a b p. 179.