German Revolution 1848/1849

The German Revolution of 1848/49 - also referred to as the March Revolution in relation to the first phase of the revolution in 1848 - was the revolutionary event that occurred between March 1848 and July 1849 in the German Confederation . The surveys also affected provinces and countries outside the federal territory that were under the rule of the most powerful federal states Austria and Prussia , such as Hungary , Northern Italy and Posen .

The associated events were part of the liberal , bourgeois - democratic and national unity and independence uprisings against the restoration efforts of the ruling houses allied in the Holy Alliance in large parts of Central Europe (see European Revolutions 1848/1849 ). As early as January 1848, Italian revolutionaries had risen against the rule of the Austrian Habsburgs in the north of the Apennine peninsula and the Spanish Bourbons in the south. After the beginning of the French February Revolution , the German states also became part of these surveys against the restoration powers that had ruled from 1815 after the end of the Napoleonic Wars (see also the democratic movement in Germany ).

In the German principalities , the revolution began in the Grand Duchy of Baden and within a few weeks spread to the other federal states. From Berlin to Vienna it forced the appointment of liberal governments in the individual states (the so-called March Cabinets ) and the holding of elections to a constituent national assembly , which met on May 18, 1848 in the Paulskirche in the then free city of Frankfurt am Main . According to the March gains relatively quickly-won successes, such as lifting of press censorship or emancipation , the revolutionary movement from the middle of 1848 was increasingly on the defensive. The high points of the surveys that flared up again , especially in the autumn of 1848 and during the imperial constitution campaign in May 1849, which regionally (for example in Saxony , the Bavarian Palatinate , the Prussian Rhine Province and above all in the Grand Duchy of Baden) assumed civil war-like proportions, could ultimately lead to the failure of the No longer stopping the revolution in relation to its essential core requirement. By July 1849, the first attempt to create a democratically constituted, unified German nation-state was suppressed by predominantly Prussian and Austrian troops with military force.

The persecution of supporters of a liberal, republican-democratic or socialist orientation that went hand in hand with the suppression of the revolution and the subsequent era of reaction caused tens of thousands to flee the German states in the years after 1848/49. At first they found asylum mainly in France, England or Switzerland . Many, who could afford a ship voyage lasting several weeks, looked for themselves and their families overseas for the personal and political freedoms that were denied them in their original homeland. In Australia and the USA , the term Forty-Eighters is used to describe the immigrants who fled German countries between the end of the 1840s and the mid-1850s.

Historical classification

Interest Groups

The revolutionaries in the German states strove for political freedoms in the sense of democratic reforms and the national unification of the principalities of the German Confederation. Above all, they represented the ideas of liberalism . However, in the further course of the revolution and thereafter, this split increasingly in different directions, which set different priorities in key areas and sometimes opposed each other (e.g. in the attitude to the importance of the nation, the social question, economic development, civil rights, as well as to the Revolution itself).

Circles with radical democratic, social revolutionary, early socialist and even anarchist goals were also heavily involved in the local revolutionary activities and uprisings . These had a predominantly extra-parliamentary effect, in parliaments they were underrepresented or not represented at all. They were therefore unable to assert themselves in the governing bodies of the revolution.

Outside the German Confederation, countries and regions that were affiliated to the Habsburg Empire sought to become independent from its supremacy. These included Hungary , Galicia and the northern Italian principalities. In addition, the revolutionaries in the predominantly Polish-inhabited province of Posen campaigned for the separation from Prussian rule.

Of the five powerful European states, the European pentarchy , only England and Russia remained untouched by the events, with Russia apart from the participation of the Russian military in the suppression of the Hungarian uprising against the Austrian Empire in 1849. In addition, Spain , the Netherlands and the young remained and Belgium, which is comparatively liberal anyway, was largely uninvolved in the events of the revolution.

Significance for Central Europe

In most states, the revolution was suppressed by 1849 at the latest. The republic lasted in France until 1851/1852. Only in the kingdoms of Denmark and Sardinia-Piedmont did the successes of the revolution last for a long time. For example, the constitutional changes that were implemented in constitutional monarchies persisted into the 20th century. The constitution of Sardinia-Piedmont became the basis for the Kingdom of Italy, which was enforced in 1861 (cf. Risorgimento ).

A lasting result of the bourgeois democratic efforts in Central Europe since the 1830s was the transformation of Switzerland from a loose and politically very heterogeneous confederation into a liberal federal state . The new Federal Constitution of 1848 made possible by the Sonderbund War of 1847 determines its basic state and social structures to this day.

Although the nation-state goals of the March Revolution in particular failed with its fundamental concerns for change and resulted in a period of political reaction , historically the wealthy bourgeoisie prevailed with it and ultimately became a politically and economically influential power factor alongside the aristocracy . From 1848 at the latest, the bourgeoisie , in the narrower sense the upper bourgeoisie , became the economically ruling class of Central European societies. This rise began with the political and social struggles since the French Revolution of 1789 (see also the bourgeois revolution ).

The revolutions of 1848/49 shaped the political culture and the pluralistic understanding of democracy of most of the states of Central Europe in the modern era in a long-term and lasting manner: in the Federal Republic of Germany (whose constitution is based on the draft constitution drawn up in the Paulskirche in Frankfurt in 1848/49), in Austria , France , Italy , Hungary , Poland , Denmark and Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic and Slovakia ). With the events of 1848/49 the triumphant march of bourgeois democracy was initiated, which in the long term determined the later historical, political and social development of almost all of Europe .

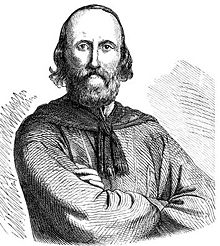

In addition to previous developments based on the Enlightenment, the March Revolution provided some ideal impulses for the development of the European Union (EU) in the late 20th century. The Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini represented a Europe of peoples even before the revolutionary turmoil around 1848 . He set this utopia against the Europe of the authoritarian principalities and thereby anticipated a basic political and social idea of the EU. Mazzini's corresponding ideas had already been taken up in 1834 by some idealistic republican Germans, among them Carl Theodor Barth , in the secret society Young Germany . Together with Mazzini 's Young Italy and Young Poland , founded by Polish emigrants , they also formed the supranational secret society Young Europe in Bern, Switzerland, in 1834 . The spirit of optimism at the beginning of the March Revolution was often shaped by their ideals, when in many places the revolutionary base was talking about an "International Spring of Nations ".

History and causes

Economic and social backgrounds

A direct harbinger of the March revolutions in what was then Central Europe was the crisis year of 1847, which was preceded by a bad harvest in 1846. This resulted in famines in almost all German states and regions as well as various hunger riots as a result of the rise in food prices , such as the so-called " potato revolution " of April 1847 in Berlin. Many groups of the population, including poorer ones, affected by pauperism (pre-industrial mass poverty) such as workers, impoverished craftsmen, agricultural workers, etc., then increasingly joined the demands of democratic and liberal-minded circles due to their social hardship. One consequence of the crisis was the decline in purchasing power for industrial products, especially textiles, which the decline of the still strong artisanal textile sector led. In the German federal states, many families still worked in the textile industry in minimally paid home work for a few wealthy entrepreneurs and landowners. The decline not only of the textile industry, but of the handicrafts in general , was also due to the advancing industrial revolution in Europe, which - starting in England - gradually affected social, economic and industrial conditions as early as the middle of the 18th century due to technical inventions fundamentally changed the entire continent. In addition, there was such a population growth that the increasingly productive agricultural economy in the country and the industry in the cities could no longer absorb the mass of labor that had been created. The result was mass unemployment. The surplus labor formed an " industrial reserve army ". More and more people were looking for work in factories and the newly emerging factories in the fast-growing cities , where many products could be manufactured more cheaply through more rational mass production .

A new stratum of the population, the proletariat (the employed working class ), grew rapidly. Working and living conditions in and around industrial companies were generally catastrophic in the 19th century. Most workers lived in the ghettos and slums of the cities on the edge of the subsistence level or often below it, threatened with unemployment and without social security. Years before the March Revolution, there had been repeated small, regionally limited uprisings against industrial barons. For example, the weavers' revolt of June 1844 in Silesia , a hunger revolt by the weavers from Langenbielau and Peterswaldau , was the first significant uprising of the German proletariat in the national public as a result of the social hardship caused by industrialization . However, the uprising was suppressed by the Prussian military after just a few days .

The wealthier bourgeoisie also saw themselves increasingly restricted in their economic development. Due to the customs policy of the principalities, the possibilities of free trade were severely limited. Demands for a liberalization of the economy and trade had also become louder in the first decades of the 19th century in the German states. On March 22, 1833, the German Customs Union was founded, which simplified trade in the German states. As a result, at the end of the 1830s there was an overall economic upswing. However, little changed in the social hardship of the poorer sections of the population.

Political background

A major goal of the March Revolution was to overcome the restoration policy that had shaped the time since the Congress of Vienna in 1815. It prevented a federal reform with the expansion of the institutions, as was already considered when the federal government was founded.

One of the most important advocates of the political restoration was the reactionary Austrian diplomat and State Chancellor Prince Klemens Wenzel von Metternich . The policy of restoration adopted by most European states at the Congress of Vienna on June 9, 1815 - immediately before Napoleon Bonaparte's final defeat at the Battle of Waterloo (June 18, 1815) - was intended to be politically domestic and interstate Restore the power relations of the Ancien Régime in Europe as they had prevailed before the French Revolution of 1789. This meant the domination of the nobility and the restoration of their privileges. Furthermore, the Napoleonic reorganization of Europe, which had also established civil rights with the Code civil , should be reversed.

Domestically, in the course of the Restoration, calls for liberal reforms or for national unification were suppressed, censorship measures tightened and freedom of the press severely restricted. The works of literary Junge Deutschland , a group of young revolutionary writers, were censored or banned. Other socially critical or nationalist poets were also affected by the censorship, so that some of them had to go into exile - especially to France or Switzerland. Well-known examples are Heinrich Heine , Georg Herwegh , Georg Büchner (who with the pamphlet Der Hessische Landbote spread the slogan “Peace to the huts, war to the palaces!”) Or Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben (the poet of the Deutschlandlied ).

Above all, the student fraternities at that time supported the demand for national unification and democratic civil rights. As early as October 1817, at a major demonstration on the occasion of the fourth anniversary of the Battle of Leipzig and the 300th anniversary of the Lutheran Reformation near the Wartburg, the so-called Wartburg Festival , they vehemently advocated German unity. There was also a public book burning when a minority of the demonstrators burned state symbols and mock-ups of works by “un-German” writers who were described as reactionary (see the book burning at the Wartburg Festival in 1817 ).

Corresponding activities inspired by the Wartburg Festival drew the state authorities' attention to the fraternities, which were exposed to increasing repression . These repressions were given legal form in 1819 as the Karlsbad Decisions , which were a reaction to the murder of the poet August von Kotzebue by the radical democratic fraternity member Karl Ludwig Sand , who was considered fanatical nationalist . Despite the ban and persecution, members of the fraternities often remained active underground . In some cases, apparently non-political cover organizations were set up and expanded, such as the gymnastics movement of " Turnvater Jahn ", where liberal and national ideas culturally influenced by Romanticism were still cultivated, but which also had anti-emancipatory and anti-enlightenment traits in them. Overall, there was also a widespread, predominantly religiously motivated anti-Judaism in these groups . This had an impact among others in the of Würzburg outgoing Hep-Hep riots of 1819, which in many places pogrom-like escalated against the Jewish emancipation focused in general and against the economic emancipation of the Jews in particular.

The July Revolution of 1830 in France, in which the reactionary royal house of the Bourbons under Charles X had been overthrown and the bourgeois-liberal forces installed the “citizen king” Louis Philippe of Orleans , gave new ones to the liberal forces in Germany and other regions of Europe Boost. As early as 1830, regionally limited uprisings had occurred in various German principalities, such as Braunschweig , Kurhessen , the Kingdom of Saxony and Hanover , some of which had led to constitutions in the respective states.

In the Italian states as well as the Polish provinces of Austria, Prussia and Russia ( Congress Poland ) there had been uprisings in 1830 with the aim of national autonomy . In the United Kingdom of the Netherlands , the Belgian Revolution led to the secession of the southern provinces and the establishment of an independent Belgian state as a parliamentary monarchy .

Overall, however, Metternich's system was initially retained, even if cracks appeared everywhere. Even after the Karlovy Vary resolutions, despite the " demagogue persecution ", there were further spectacular gatherings similar to the Wartburg Festival, such as the Hambach Festival in 1832, at which the forbidden republican black, red and gold flags were demonstratively displayed.

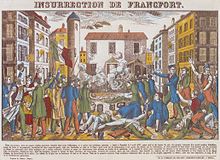

The Frankfurt Wachensturm on April 3, 1833 was the first attempt by around 50 students to trigger an all-German revolution. The action was directed against the seat of the German Bundestag , which the Democrats viewed as an instrument of restoration policy. After the storming of the two Frankfurt police stations, the rebels wanted to capture the princes' ambassadors in the Bundestag and thus set the tone for an all-German uprising. The action, which had already been betrayed in advance, failed in the beginning after an exchange of fire in which there were some dead and injured.

course

introduction

A key factor behind the March revolutions was the success of the February revolution in France in 1848 , from where the revolutionary spark quickly spread to the neighboring German states. The events in France, where it was possible to depose the citizen-king Louis Philippe , who had in the meantime visibly abandoned liberalism , and finally to proclaim the Second Republic , set in motion revolutionary upheavals whose turmoil kept the continent in suspense for a year and a half.

The most important centers of the revolution after France were Baden , Prussia , Austria , Northern Italy , Hungary , Bavaria and Saxony . But also in other states and principalities there were uprisings and popular assemblies at which the revolutionary demands were articulated. Based on the Mannheim people's assembly on February 27, 1848, at which the “ March demands ” were formulated for the first time, the core demands of the revolution in Germany were: “1. Arming the people with free election of officers, 2. Unconditional freedom of the press, 3. Jury courts based on the example of England, 4. Immediate establishment of a German parliament. "

In the Kingdom of Denmark , the revolutionary events of 1849 resulted in a new constitution in which a constitutional monarchy and a bicameral parliament with universal suffrage were introduced.

In some states of the German Confederation, for example in the kingdoms of Württemberg and Hanover , or in Hesse-Darmstadt , the princes quickly gave way. Liberal " March Ministries " were soon set up there , some of which complied with the demands of the revolutionaries, for example by setting up jury courts , abolishing press censorship and liberating the peasants . Often, however, it was just a promise. In these countries the revolution was reasonably peaceful because of the early concessions.

As early as May / June 1848, the ruling royal houses began to intensify restorative activities, which increasingly pushed the rebels in the states of the German Confederation on the defensive. The suppression of the June uprising in Paris in the further course of the French February Revolution was a decisive event for the onset of the counterrevolution (“ reaction ”) in the other European states as well. The June uprising of the Parisian workers is also historically seen as a marker for the split between the revolutionary proletariat and the bourgeoisie .

A chronological course of the revolution in its entirety is difficult to grasp, since the events cannot always be clearly related to one another, decisions were made on different levels and in different places, sometimes almost simultaneously, sometimes at different times, and then revised.

Timetable

Pre-revolutionary development

- September 18, 1814 to June 9, 1815: Congress of Vienna . The decision to “reorganize” Europe introduces the restoration policy . The phase of the political “ pre-march ” begins .

- October 18, 1817: German unity is called for at the Wartburg Festival .

- Late summer – autumn 1819: In most of the states of the German Confederation, the Hep-Hep riots lead to anti-Jewish riots that are directed against the emancipation of Jews and escalate in a pogrom-like manner in some places.

- September 20, 1819: As a result of the murder of the poet August von Kotzebue , the Karlovy Vary resolutions created the legal basis for repression against the democratic and national efforts of the fraternities and other opposition groups, e. B. through bans on democratic groups and associations, press censorship, etc.

- July 1830: The July revolution in France also triggers some regionally limited uprisings in the states of the German Confederation, such as the tailor revolution in Berlin.

- May 27, 1832: At the Hambach Festival , calls for a unified Germany and for democratic rights are again made.

- April 3, 1833: The attempt at an all-German revolutionary uprising fails at the Frankfurt Wachensturm .

- 1834: In Bern , the secret societies Young Italy , Young Germany and Young Poland formed by exiled democrats unite on the initiative of the Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini to form the supranational secret society Young Europe .

- 1834: Georg Büchner and Friedrich Ludwig Weidig distribute the social revolutionary pamphlet Der Hessische Landbote from the underground in the Grand Duchy of Hesse with the motto “Peace to the huts, war to the palaces!”.

- 1837: The protest proclamation of the Göttinger Sieben (a group of well-known liberal university professors, including the Brothers Grimm ) against the repeal of the constitution in the Kingdom of Hanover , spread throughout the German Confederation. The scholars are dismissed and some of them are expelled from the country.

- June 1844: In a region of Silesia the weavers rise up due to increasing social hardship ( weaver revolt ).

- April 1847: The so-called Berlin Potato Uprising as a result of increased food prices due to bad harvests in the previous year is crushed by the Prussian military after a few days.

- September 12, 1847: At the Offenburg assembly , radical democratic Baden politicians demanded basic rights with the “demands of the people” and countered the industrialization perceived as a threat from early socialist ideas.

- October 10, 1847: At the Heppenheim conference , the political program of the moderate liberals is formulated.

Transitional phase to the March Revolution from January 1848

- January 1848: National revolutionary uprisings against the rule of the Spanish Bourbons in southern Italy ( Sicily ) and against that of the Austrians in northern Italy ( Milan , Padua and Brescia ) usher in the pan-European phase of the revolutions of 1848/49.

- February 24, 1848: Beginning of the February Revolution of 1848 in France. Proclamation of the Second Republic . Prime Minister François Guizot resigns. Citizen King Louis Philippe abdicates and goes into exile in England.

Revolutionary development in 1848

- February 27, 1848: Inspired by the February Revolution in France, the Mannheim People's Assembly formulates a petition to the government in Karlsruhe with so-called March demands and thus becomes a beacon of the March Revolution in the states of the German Confederation.

- February 29: The Bundestag sets up a political committee made up of representatives from the Bundestag; In the coming weeks the Bundestag will pass several federal resolutions with the aim of appeasing the unrest among the people.

- March 1: Beginning of the March Revolution in Baden with the occupation of the state house of the Baden state parliament in Karlsruhe.

- March 4: Beginning of the March Revolution in Bavaria with uprisings in Munich

- March 5: The Heidelberg Assembly invites you to the pre-parliament .

- March 6th: Beginning of the March Revolution in Prussia with the first unrest in Berlin

- March 9: Under pressure from the opposition, King Wilhelm I of Württemberg appoints the opposition leader Friedrich Römer as head of government and several liberals into the government instead of the conservative Joseph von Linden, and appoints them as the March Ministry .

- March 13: Beginning of the March Revolution in Vienna with the storming of the Ständehaus; Resignation of the State Chancellor, Prince Metternich , who emigrates to England.

- March 15: Under the impression of 20,000 demonstrators, the governor's council in Pest (now Budapest ), the highest administrative body of the Hungarian part of the Austrian Empire , approves the demands of radical Hungarian intellectuals around Sándor Petőfi (including one who is independent from Vienna ), formulated in "Twelve Points" Ministry and independent Hungarian parliament, withdrawal of all Austrian troops from Hungary, the establishment of a Hungarian national army and the creation of a national bank) and thus turns the Kingdom of Hungary into a de facto independent state.

- March 17th: Milan declares the separation of Lombardy from Austria and its connection to the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont .

- March 18: When King Friedrich Wilhelm IV's patent was read out on reforms in Prussia, an armed struggle between citizens and the military ensues at a meeting in front of the Berlin City Palace . During the reading, after an initially peaceful atmosphere, revolutionary slogans are loud. Two shots go off, whether on purpose or from a misunderstanding, is never resolved. This is followed by a change in the mood of the demonstrators and the targeted deployment of the military. Fierce street and barricade fighting ensued and claimed several hundred deaths, according to the authorities, 303 people, 288 men, 11 women and 4 children.

- March 19: King Friedrich Wilhelm IV. Is forced to appear in front of the “ March fallen ” in the courtyard and to pull off his hat. On March 21, he rides through Berlin with a black, red and gold sash and declares that he wants Germany's freedom, Germany's unity .

- MARCH 20: abdication of the Bavarian King Ludwig I in favor of his son Maximilian II. As a result of unrest in Munich and other cities in Bavaria

- 18.-22. March: The popular uprising in Milan against the rule of Austria in Lombardy leads to the First Italian War of Independence between Austria and Sardinia-Piedmont , whose troops support the northern Italian revolutionaries.

- March 23: Revolution in Venice - Daniele Manin proclaims independence from Austria and declares the city a republic (cf. Repubblica di San Marco ).

- March 31 to April 3: The pre-parliament meets in Frankfurt am Main .

- Beginning of April: Beginning of the Schleswig-Holstein uprising as a result of the national German uprisings in the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein . Both German and Danish national liberals claimed the Duchy of Schleswig, which was still formally a royal Danish fiefdom in personal union with Denmark.

- April 12 to April 20: The Republican-motivated Hecker procession in Baden was put down on April 20 in a battle on the Scheideck near Kandern in the Black Forest, Lieutenant General Friedrich von Gagern fell as commander of the federal troops. Friedrich Hecker goes into exile .

- April – May: Uprising of the Poznan Poles against Prussian supremacy under the leadership of Ludwik Mieroslawski

- May 15th: Second Viennese uprising

- May 17: Emperor Ferdinand I flees Vienna to Innsbruck under the pressure of the revolutionary unrest.

- May 18: Opening of the Frankfurt National Assembly in the Paulskirche , the first all-German democratically elected parliament; it is supposed to prepare German unity and work out a constitution for the new unified state.

- June 2nd - December 12th June: The Slavs Congress meets in Prague and calls for the transformation of the Danube Monarchy Austria "into a union of peoples with equal rights".

- June 16: Suppression of the Whitsun uprising in Prague by Austrian troops

- June 24th: The French June uprising is put down in Paris. After that, the counter-revolution also strengthened in the states of the German Confederation and increasingly forced the revolutionaries on the defensive.

- July 25th: The northern Italian insurgents, led by Sardinia-Piedmont, are defeated by the Austrian troops in the battle of Custozza .

- August 9: Armistice between Austria and Sardinia-Piedmont

- August 26th: Armistice between Prussia and Denmark. The National Assembly finally has to approve the Malmö Treaty on September 16, revealing its own powerlessness. The crisis leads to new unrest in Frankfurt am Main ( September Revolution ) and other German cities.

- September 12: The republican nationalist leader Lajos Kossuth becomes Prime Minister in Hungary. The Austrian emperor is denied the title of "King of Hungary". There was national revolutionary unrest against the supremacy of Austria.

- September 18: Barricade fighting against Prussian and Austrian troops in Frankfurt: September Revolution

- 21-25 September: 2nd Baden uprising in Loerrach ; Gustav Struve , who proclaimed the German republic on September 21, was subsequently arrested.

- 6-31 October: After just under four weeks, the Vienna October Uprising is bloodily suppressed by imperial troops under Prince Windischgrätz .

- November 9th : Robert Blum , member of the Frankfurt National Assembly, is shot dead in the course of retaliation against the Austrian revolutionaries in Vienna, demonstratively disregarding parliamentary immunity.

- November 21: Constitution of the Central March Association as a nationwide republican organization by members of various parliamentary groups of the democratic left in the Frankfurt National Assembly

- December 2: The Austrian Emperor Ferdinand I abdicates and leaves the throne to his nephew Franz Joseph I.

- December 27: The National Assembly in Frankfurt adopts the basic rights of the German people .

Revolutionary development in 1849

- February – March: New uprisings in some Austrian regions of northern Italy, in particular the revolutionary coup against Grand Duke Leopold II in Tuscany, lead to another war between Austria and Sardinia-Piedmont .

- March 23rd: Another defeat of the northern Italian revolutionaries and Sardinia-Piedmont against the Austrian army in the battle of Novara

- March 28th: After many controversial debates, the National Assembly adopts the Paulskirche constitution .

- April 3: The Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV refuses the Imperial Crown offered to him by the National Assembly ( Imperial Deputation ). With this, German unity and the imperial constitution failed.

- April 14th: Hungary declares its independence from Austria and proclaims a republic. Then it comes to the Hungarian War of Independence against Austria.

- May: In the May uprisings, the Reich constitution campaign begins with an attempt to enforce the constitution in some states and regions of the German Confederation - and to install individual republics as well. The confrontation between revolution and reaction leads to a civil war escalation in some states . In addition to Saxony and Baden, for example, the Prussian Rhine province and the neighboring province of Westphalia (→ Iserlohn revolt of 1849 and revolution of 1848/49 in Westphalia ) and the Palatinate (Bavaria) ( Palatinate revolt ) are centers of such uprisings.

- 3rd-9th May: During the May uprising in Dresden , a Saxon republic is proclaimed, which fails due to the suppression of the uprising by Prussian troops.

- May 11th: Mutiny of the Baden garrison in Rastatt : Beginning of the Baden May Uprising.

- May 13: Grand Duke Leopold von Baden leaves the country.

- June 1st: The Republic is proclaimed in Baden. Lorenz Brentano takes over the presidency of the provisional government. Prussian troops begin to advance towards Baden.

- 6-18 June: The rump parliament, the remnant of the National Assembly, meets in Stuttgart ; it is dissolved by Württemberg troops on June 18 .

- July 23: Rastatt is captured by Prussian troops, end of the Baden Revolution and symbolic end of the German Revolution of 1848/49

Aftermath until October 1849

- August 6th: Milan peace treaty between Austria and Sardinia-Piedmont

- August 23: Austrian troops crush the revolutionary republic of Venice. Upper Italy is again in Austrian hands.

- October 3: The last Hungarian revolutionaries capitulate to the Austrians in the Komorn Fortress .

Developments in the countries

bathe

On February 27, 1848, a people's assembly had already taken place in Mannheim , at which the fundamental demands of the revolution were anticipated. The Baden revolutionaries, especially their strongly represented radical democratic wing, demanded the most far-reaching changes.

Under the leadership of the lawyers Friedrich Hecker and Gustav Struve , they demanded, among other things, the creation of actual popular sovereignty , the abolition of noble privileges , popular arming and a progressive income tax . In doing so, they were already making social revolutionary and socialist demands.

As representatives of the left wing in the Frankfurt pre-parliament , which was supposed to prepare the elections for a constituent national assembly , Struve and Hecker had called for a federal German republic with not only political but also social changes. A corresponding program published by Struve was rejected by the majority of the pre-parliament.

Thereupon Hecker, Struve and their supporters tried their own way, starting from southwest Germany , in the so-called " Hecker uprising ". In Constance they supposedly proclaimed the republic on April 12, 1848, together with the Bonn university professor Gottfried Kinkel and others; however, none of the three Konstanz newspapers mentioned this in their reports on the speech in question. The Hecker train set out with about 1200 men in the direction of the Rhine plain , where it unite with a train led by the left-wing revolutionary poet Georg Herwegh and his spy Emma , the " German Democratic Legion " from France , and headed for the Baden capital, Karlsruhe wanted to march in order to enforce the republic in all of Baden from there. Both groups were defeated and wiped out by the regular military in a short time: Hecker's Freischar on April 20, 1848 in a battle near Kandern in the Black Forest , Herwegh's Freischar a week later near Dossenbach .

Hecker was able to escape into exile , which ultimately led him to the USA via Switzerland . The Heidelberg poet Karl Gottfried Nadler took his defeat as an occasion for his mock ballad Peep box song by the great Hecker .

Another uprising of Struve in September 1848 in Loerrach , where he and his supporters proclaimed the republic on September 21, also failed. Struve was captured and in a treason trial in Freiburg with some other revolutionaries to a prison sentence convicted was freed until he Maiunruhen in 1849 again. The further revolutionary development of Baden was then essentially limited to the debates in the Frankfurt National Assembly .

In May 1849, after the National Assembly in Frankfurt had failed, there were further uprisings in Baden along with other German states, the so-called May uprisings as part of the imperial constitutional campaign . The Democrats wanted to force the recognition of their respective governments in an imperial constitution.

The Baden garrison mutinied in the federal fortress of Rastatt on May 11th. A few days later, Grand Duke Leopold fled from Baden to Koblenz . On June 1, 1849, a provisional government under the liberal politician Lorenz Brentano took over government. There were fights against federal troops and the Prussian army under the leadership of the "Kartätschenprinzen" Wilhelm of Prussia , the later German Emperor Wilhelm I. The Baden Revolutionary Army could not withstand the pressure of the overwhelming strength of the Prussian troops.

The Baden revolutionaries were under the leadership of the Polish Revolutionary General Ludwik Mieroslawski in June 1849 . Mieroslawski was a tactically skilled and experienced soldier of the revolution. In the course of the March Revolution he had already led the uprising of the Poznan Poles in 1848 against Prussian domination and other preceding Polish uprisings (see sub-article Poznan, Poland ). However, Mieroslawski resigned on July 1, 1849 as commander of the Baden revolutionary troops; he was resigned by the hesitant attitude of the Brentano government, which relied on negotiations and postponed a general arming of the people demanded by the radicals. Furthermore, the morale of the troops had declined, so that Mieroslawski ultimately saw the military situation for a success of the Baden republic as hopeless.

Brentano's indecision had led to his overthrow by Gustav Struve and his followers at the end of June 1849. But this step could not stop the process of disintegration of the revolutionary troops. Without a unified military command, the remaining committed militants had almost no chance. The downfall of the Baden revolution was basically sealed.

On the side of the Baden revolutionaries, the socialist Friedrich Engels was also actively involved in the fighting. Engels was the editor of the Neue Rheinische Zeitung published by Karl Marx in 1848/49 and a critical and sympathetic observer of the revolution. A year earlier, in February 1848, Engels and Karl Marx had published The Communist Manifesto on behalf of the League of Communists . Wilhelm Liebknecht , who was still relatively unknown at the time and later co-founder of the Social Democratic Workers' Party (SDAP), the predecessor party of the SPD , was also active as adjutant Gustav Struves on the side of the revolutionaries.

When the fortress of Rastatt fell on July 23, 1849 after a three-week siege , the Baden revolution had finally failed. 23 revolutionaries were executed, some others such as Gustav Struve , Carl Schurz and Lorenz Brentano were able to escape into exile . In total, around 80,000 people from Baden left their country after the revolution. That was about five percent of the population. Some of the prominent revolutionaries later continued their political commitment to democratic goals in the USA and made political careers there. Carl Schurz became US Secretary of the Interior in 1877 and held this post until 1881.

What was characteristic of the Baden Revolution in contrast to the other uprisings in the German Confederation was that the demand for a democratic republic was most consistently represented. In contrast, a constitutional monarchy with a hereditary emperor was favored by the majority in the committees and revolutionary parliaments of the other principalities of the German Confederation .

Prussia, Poznan, Poland

Prussia

Under the pressure of the revolutionary events in Berlin since March 6, 1848, the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV initially gave in and made concessions. He agreed to convene the state parliament , introduce freedom of the press , remove customs barriers and reform the German Confederation . After the relevant patent had been read out on March 18, two shots were fired from military rifles and displaced thousands of the citizens who had gathered on Schlossplatz. As a result, there was a barricade uprising in Berlin and street fights between the revolutionaries against the regular Prussian troops , in which the rebels were able to prevail for the time being. On March 19 the troops were withdrawn from Berlin on the orders of the King. Several hundred dead and over a thousand injured on both sides were the result of these fighting.

The king felt compelled to show his respect for the revolutionaries who had been killed. On March 19, he bowed to the laid out " March fallen " before they were buried on 22 March in the so-called " cemetery of the March fallen ". On March 21st he rode through Berlin wearing a band in the colors of the revolution black-red-gold and promised in an appeal “ To my people and to the German nation ” that Prussia would rise up in Germany. In the evening the black, red and gold flag was placed on the scaffolding of the palace dome. In a proclamation the king said:

“Today I adopted the old German colors and placed myself and my people under the venerable banner of the German Empire. From now on Prussia will be part of Germany. "

The next day Friedrich Wilhelm IV wrote secretly to his brother, Prince Wilhelm:

“Yesterday I had to put on the Reichsfarben voluntarily in order to save everything. If the throw is successful ... I put it down again! "

On March 29, 1848, a Liberal March Ministry was set up. The new government included two former, bourgeois representatives of the First United State Parliament from 1847: the Rhenish bankers Ludolf Camphausen and David Hansemann . Of course, conservative aristocrats like Karl von Reyher were also part of the Camphausen-Hansemann cabinet . They blocked reform projects. The bureaucracy and the army remained virtually unchanged in terms of personnel and structure. Until the end of April 1848, the Prussian March Ministry enjoyed great trust among the population. However, a revolutionary reorganization of the state was never in the interests of Camphausen and Hansemann. In alliance with the conservative forces and the monarchy, they only intended a “limited reform” of Prussia. On June 20, 1848, the March Ministry was abolished.

When events had calmed down somewhat at the end of May 1848, the king made a reactionary about-face. With the Berlin Zeughaussturm there was another revolutionary surge on June 14th. The people armed themselves from the arsenal. On November 2, 1848, General Friedrich Wilhelm von Brandenburg was appointed Prime Minister of Prussia. A week later the royal troops returned to Berlin. The Conservative MP Otto von Bismarck , who later became Prime Minister of Prussia and finally Chancellor of the German Reich founded in 1871, was also involved in the subsequent counter-revolution in Prussia . The negotiations of the Prussian National Assembly on a constitution that had been taking place since May 22nd, which Friedrich Wilhelm IV and his predecessor had repeatedly promised since 1815 but never implemented, ultimately remained unsuccessful. The draft constitution presented in July 1848, the " Charte Waldeck ", which provided for some liberal democratic reforms, was rejected by both the Conservative MPs and the King.

On November 10 and 15, 1848, the king had the military break up the deliberations of the Prussian National Assembly in Berlin. In Dusseldorf revolutionary forces called on November 14, 1848 for a tax boycott , an armed vigilante declared themselves "permanent" to carry out and monitor it and a little later searched the local post office for taxpayers' money the city and the government's ban on vigilante groups. On December 5, the king decreed the dissolution of the National Assembly he had moved to Brandenburg and on the same day imposed a constitution that fell far short of the demands of the March Revolution. The king's position of power remained untouched. This reserved the right of veto against all resolutions of the Prussian state parliament as well as the right to dissolve the parliament at any time. The state ministry - the Prussian government - was answerable not to parliament, but only to the king. Nevertheless, the imposed constitution initially contained some liberal concessions taken from the “Charte Waldeck”, which were, however, modified in the following months.

At the end of May 1849, the National Assembly was replaced by the Prussian House of Representatives , Second Chamber . A three-class suffrage was introduced in order to secure the domination of the haves. This undemocratic right to vote remained in force in Prussia until 1918.

This reaction led to counter-movements, especially in the western provinces of Prussia. In the electoral districts of Rhineland and the Province of Westphalia , which were formerly dominated by liberal or Catholicism, many democratic members were elected in the new elections to the Prussian House of Representatives. However, the king's troops had gained the upper hand over the revolution in May 1849 at the latest with the failure of the Iserlohn uprising in Westphalia and the Prüm armory storm in the Rhineland.

Poznan, Poland

The majority of Poles lived in the Grand Duchy of Posen 1848 was a Prussian province . The former Polish-Lithuanian state had become the political plaything of the major European powers by the end of the 18th century. After several violent partitions among Russia, Prussia and Austria, the state ceased to exist in 1795.

At the beginning of the 19th century there was only one Polish vassal state under Napoleonic protection from 1807 to 1815 , the Duchy of Warsaw under Duke Friedrich August I of Saxony, who was also King of Saxony. After the victory of the partitioning powers over Napoleon, the Duchy of Warsaw was divided between Russia and Prussia at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, recognizing an obligation to safeguard the Polish nationality of the residents.

In the period that followed, conspiracies repeatedly formed in the Polish areas of Russia, Prussia and Austria with the aim of rebuilding an independent Poland. In the wake of the French July Revolution of 1830, this led to the November uprising in the Russian part of the country , but it was unsuccessful.

In 1846 a secretly planned Wielkopolska uprising in the Grand Duchy of Poznan was uncovered and put down in the bud. Its leader, the Polish revolutionary Ludwik Mierosławski , was captured, sentenced to death in the Poland trial in Berlin in December 1847 , but then pardoned with seven others on March 11, 1848 to life imprisonment.

After the fighting in Berlin on March 18 and 19, 1848, 90 Polish revolutionaries, including Mierosławski and Karol Libelt , were released from Moabit prison. In the early stages of the March Revolution, which in Europe was perceived as the spring of nations, the revolutionaries still had a friendly attitude towards Poland, which initially welcomed and encouraged the subsequent uprising in Poznan . Shortly after his liberation in April and May 1848, Mierosławski headed the uprising of the Poznan Poles against Prussian rule, which was now perceived as German . The uprising was directed against the inclusion of predominantly Polish areas in the elections for the Frankfurt National Assembly and thus against the incorporation of part of Poland into a German nation-state. Another aim was the unification of all of Poland. In this respect, the revolution in Poznan also aimed at the liberation of the Kingdom of Poland, the so-called “ Congress Poland ”, which had been under direct Russian rule as a province since 1831 after the loss of its autonomy.

In the course of the revolution in Prussia, where conservative forces had increasingly started to determine the situation again, the initial enthusiasm for Poland had given way to a more nationalistic attitude in Prussia. In addition, the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV did not want to risk a war with Russia because of the Poznan uprising . On May 9, 1848, the uprising of the Poznan Poles was suppressed by a superior force of Prussian troops and Mierosławski was arrested again. Upon the intervention of revolutionary France, he was pardoned after a short time and expelled to France; until he was called in June 1849 by the Baden revolutionaries, who put him at the head of their revolutionary army (see sub-article Baden ).

After the revolution of 1848, the Poles in Prussia realized that a violent uprising could not lead to success. As a method to maintain national cohesion and to defend against the Prussian policy of Germanization , organic work became increasingly important in the now constitutional Prussian state.

Austria, Bohemia, Hungary, Italy and the First Italian War of Independence

Austria

In the Habsburg empire and multi-ethnic state of Austria , the monarchy was not only threatened by violent uprisings in the heartland of Austria itself, but also by further revolutionary unrest, for example in Bohemia, Hungary and northern Italy . The Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont provided the revolutionaries with military support. While the Hungarian, Bohemian and Italian uprisings sought, among other things, independence from Austrian supremacy, the revolution in the heartland of Austria, as in the other states of the German Confederation, aimed at a liberal and democratic change in government policy and the end of the restoration.

There was also a starvation winter in Austria in 1847/1848. The economic hardship hit the disadvantaged population groups hardest. In the working class too, anger at the traditional political system was on the verge of boiling over. Works such as Alfred Meissner's Neue Sklaven or Karl Beck's poem Why we are poor give a vivid picture of the anger and despair that prevailed among the population.

Finally, on March 13, 1848 in Vienna, with the storming of the Estates building and attacks by social revolutionaries against shops and factories in the suburbs, the revolution in Austria broke out. The song What comes there from the height , where the "height" referred to the police and the barracks, became the song of the revolution. It is still sung today by various student associations to commemorate the participation of the Academic Legion. Were in an already on 3 March 1848 by the Hungarian before the storm to the House of the Estates nationalists -guide Lajos Kossuth written speech, the resentment against the political system and the demands of the revolutionaries for constitutional transformation of the monarchy and by the constitutions of the Austrian countries expressed. This speech was read out by Adolf Fischhof at the meeting of the estates . The attempt to deliver a petition to Emperor Ferdinand turned into a real demonstration, so that Archduke Albrecht gave the order to fire and the first deaths occurred.

On the evening of March 13th, State Chancellor Prince Metternich , the hated 74-year-old symbol of the Restoration, resigned and fled to England . This event was thematized , for example, by Hermann Rollett's poem Metternich's Linde .

On March 14, Emperor Ferdinand I made the first concessions: He approved the establishment of a national guard and lifted censorship . On the following day he specified this to the effect that he had " granted complete freedom of the press " and at the same time promised the enactment of a constitution (the so-called constitutional promise of March 15, 1848, see picture next door).

On March 17th the first responsible government was formed; its interior minister Franz von Pillersdorf drafted the Pillersdorf constitution , named after him , which was announced on April 25, 1848 for the emperor's birthday party. This constitution had an early constitutional character ; Above all, the two-chamber system and the Reichstag election regulations published on May 9th caused outrage, which led to renewed unrest (“May Revolution”). Due to the “storm petition” of May 15, the constitution was changed so that the Reichstag should only consist of one chamber and was also declared to be “constituent”, that is, it had the task of drawing up a definitive constitution first; the Pillersdorf constitution remained in effect as a provisional arrangement. The overstretched emperor, weak in leadership, escaped the increasing unrest on May 17, 1848 by fleeing to Innsbruck .

On June 16, Austrian troops led by Prince Alfred zu Windischgrätz put down the Whitsun uprising in Prague .

On July 22, 1848, the constituent Austrian Reichstag was opened by Archduke Johann with 383 delegates from Austria and the Slavic countries . Among other things, the peasants' exemption from inheritance was decided there at the beginning of September .

As a result of the events in Hungary since September 12, 1848, when the Hungarian uprising led by Lajos Kossuth culminated in a military conflict against the imperial troops, and as a result of the murder of the Austrian Minister of War Theodor Graf Baillet von Latour on October 6, the third phase of the Austrian revolution, the so-called Viennese “ October Revolution ” , took place in Vienna . In the course of this, the citizens of Vienna, students and workers succeeded in taking control of the capital after the government troops had fled. But the revolutionaries could only hold out for a short time.

On October 23, Vienna was surrounded by counter-revolutionary troops from Croatia under the Banus Joseph Jellačić and from Bohemian Prague under Field Marshal Alfred Fürst zu Windischgrätz . Despite the fierce but hopeless resistance of the Viennese population, the city was retaken by the imperial troops after a week. Around 2,000 insurgents had fallen. Other leaders of the Viennese October Revolution were to death or long prison sentences convicted.

Among the victims who were legally shot was the popular left-liberal republican member of the Frankfurt National Assembly, Robert Blum , who was executed on November 9, 1848 despite his parliamentary immunity and thus became a martyr of the revolution. In literary terms, this event was processed in the (folk) "Song of Robert Blum" , which was sung mainly in the German states outside Austria.

On December 2, 1848 there was a change of throne in Austria . The revolutionary events had made Emperor Ferdinand I's weak leadership clear. On the initiative of the Austrian Prime Minister, Lieutenant Field Marshal Felix Fürst zu Schwarzenberg , Ferdinand abdicated and left the throne to his 18-year-old nephew Franz, who assumed the emperor name Franz Joseph I. With this name he leaned consciously on his great-great-uncle Joseph II (1741–1790), whose politics had stood for a willingness to reform .

This put down the revolution in Austria. The constitution drawn up in March never came into force. However, the events in Hungary and Italy initially remained an obstacle for Franz Joseph I to assert his claim to power in the entire Habsburg Empire.

From a cultural point of view, the year 1848 was marked by the brief lifting of censorship. As a result, a large number of works were published, magazines shot up and disappeared again and the writing culture changed fundamentally. Friedrich Gerhard's “Die Presse frei!” , MG Saphir's “Der tote Zensor” , the censor song or Ferdinand Sauter's “Geheime Polizei” give an idea of the spirit of optimism. There was also sharp criticism of the existing system. Examples of this can be found in Johann Nestroy's Freiheit in Krähwinkel , The Old Man with the Young Woman , Sketches on Hell's Fear , Lady and Tailor or Die liebe Anverwandten (1848), in the political poems of Anastasius Grün and in the writings of Franz Grillparzer : " To the Fatherland ” and “ Thoughts on Politics ” .

Bohemia

In June 1848 the Whitsun Uprising in Prague broke out in Bohemia . The uprising was preceded by the Slavs Congress , also held in Prague from June 2 to 12 , in which the anarchist Mikhail Bakunin was the only Russian to take part alongside the Poznan Poles and Slavic Austrians . The participants in the congress demanded the transformation of the Danube monarchy into a union of peoples with equal rights. The demand for a Czech nation-state was expressly rejected; instead, only autonomy rights vis-à-vis the Austrian central government were sought. The Austrian Emperor Franz Ferdinand I strictly rejected these demands. Czech revolutionaries then began the Pentecostal uprising against Austrian rule. The uprising was suppressed on June 16, 1848 by Austrian troops under Alfred Fürst von Windischgrätz .

Hungary

In Hungary, where Lajos Kossuth , until then Finance Minister and Chairman of the Defense Committee , succeeded the liberal Prime Minister Lajos Batthyány on September 12, 1848 , the Austrian Emperor Ferdinand I was refused recognition as King of Hungary as a result of the revolutionary events in Austria .

The imperial decree of the October Constitution on March 7, 1849, led to the independence uprising. To put down the uprising, an imperial army marched into Hungary under Alfred Fürst zu Windischgrätz . However, this had to withdraw on April 10, 1849 in front of the revolutionary army, reinforced with free troops and Polish emigrants.

On April 14, 1849, the Hungarian Reichstag declared its independence from the House of Habsburg-Lorraine and proclaimed the Republic . Kossuth was then declared the Hungarian imperial administrator . As such, he had dictatorial powers.

The other European states, however, did not recognize independence. Therefore, Russian troops assisted the Austrian army and ultimately together put down the Hungarian revolution. On 3 October 1849 came to the fortress Komárom to surrender the last Hungarian units. In the days and weeks that followed, over a hundred leaders of the Hungarian uprising were executed in Arad . On October 6, 1849, the first anniversary of the October Uprising in Vienna, the former Prime Minister Batthyány was executed in Pest .

Lajos Kossuth, the politically most important representative of the Hungarian freedom movement , was able to go into exile in August 1849 . Until his death in Turin in 1894 , he stood up for the independence of Hungary.

Italian provinces and states

In the 19th century, after the military termination of Napoleonic hegemony in Europe and also in the Italian principalities, Italy consisted of various individual states. The northern Italian regions ( Lombardy , Veneto , Tuscany and Modena ) were under Austrian sovereignty. At the latest since the 1820s, the Risorgimento (“resurrection”) revolts had come about, which sought a unified Italian state and thus also directed against Austrian rule in northern Italy . From the underground, the groups around the radical democratic national revolutionaries Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi were particularly active in the 1830s, when they initiated several uprisings in various regions of Italy in the wake of the French July Revolution, but all of them failed.

These revolutionaries also played an important role in Italy during the March Revolution. Mazzini's theses of a united, free Italy in a Europe of peoples liberated from monarchical dynasties , which were published in the forbidden newspaper Giovine Italia (" Young Italy "), not only influenced the revolutions in the Italian states, but were also significant for the radical democratic currents in many other regions of Europe.

The revolutionary events of 1848 found a strong echo not only in northern Italy but also in other Italian provinces. As early as January 1848, in Sicily , Milan , Brescia and Padua , the first uprisings of Italian freedom fighters against the predominance of the Bourbons in the south and that of the Austrians in the north, which increased on March 17, 1848 in Venice and Milan. In Milan, the revolutionaries declared the independence of Lombardy from Austria and the annexation to the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont . This situation finally led to the war between Sardinia-Piedmont and Austria (see First Italian War of Independence ).

King Charles Albert of Sardinia-Piedmont, who has an oriented to France in his state on March 4th 1848 representative constitution was adopted, with whom he is a constitutional monarchy introduced the revolutionary mood would use to Italy under his leadership to one. After Karl Albert's initial successes, however, on July 25, 1848, at the Battle of Custozza near Lake Garda, the King's troops were defeated by the Austrians under Field Marshal Johann Wenzel Radetzky . In the armistice of August 9, Lombardy had to be ceded to Austria. Only Venice remained unoccupied for the time being. Italian revolutionaries declared the city independent on March 23, 1848 and proclaimed the Repubblica di San Marco under the leadership of Daniele Manin .

When, in February 1849, insurgents finally put on a coup against Grand Duke Leopold II of Habsburg in Tuscany, war broke out again. This was again decided in favor of the imperial Austrians under Radetzky in their victory on March 23, 1849 in the battle of Novara against the 100,000-strong army of Sardinia. This crushed the Italian unification movement for the time being and essentially restored Austrian supremacy in northern Italy. King Karl Albert of Sardinia-Piedmont abdicated in favor of his son Viktor Emanuel II and went into exile in Portugal . The new king signed a peace treaty with Austria on August 6th in Milan .

As the last bastion of the northern Italian uprisings of 1848/49, the revolutionary republic of Venice was crushed on August 24, 1849. Radetzky received the post of general, civil and military governor of Lombardy-Veneto from the emperor .

Revolutionary unrest also broke out in many non-Austrian areas of Italy in 1848/49, for example in the Kingdom of Naples - Sicily , also known as the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies , where revolts had already broken out in January 1848, whereupon King Ferdinand II of Naples and Sicily issued a constitution.

Pope Pius IX fled Rome from the worsening unrest in November 1848 and left the Papal States . He went to Gaeta on the coast of Naples-Sicily. On February 9, 1849, the Roman revolutionaries called by Giuseppe Mazzini , the Republic of the Papal States from. On July 3, 1849, the Roman Revolution was suppressed by French and Spanish troops, which in part led to protests in France itself, for example in Lyon . After the uprising was crushed, power was taken over by an executive committee made up of cardinals. The Pope did not return until 1850, reversed most of the reforms introduced in 1846 and established police-state relations.

Bavaria

Since March 4, 1848, there has been an increasing number of democratically and liberally motivated unrest and uprisings in Bavaria . On March 6, the Bavarian King Ludwig I gave in to some of the demands of the revolutionaries and appointed a more liberal cabinet. However, the king was in another crisis because of his inappropriate relationship with the supposedly Spanish dancer Lola Montez , to whom he partially subordinated the state business. This affair also brought criticism from the conservative- Catholic camp to Ludwig . On March 11, 1848, Lola Montez was banished from Munich . New unrest broke out when it was said that the dancer had returned. Thereupon the king finally abdicated in favor of his son, Maximilian II .

After the failure of the Paulskirche constitution , as in some other regions of Germany, as part of the imperial constitution campaign , the Palatinate uprising took place in May 1849 in the Palatinate (Bavaria) . In the course of this uprising, the Rhine Palatinate was briefly split off from Bavarian rule. However, the uprising was quickly crushed by Prussian troops .

Grand Duchy of Hesse

In the Grand Duchy of Hesse, Grand Duke Ludwig II and his chief minister, Karl du Thil , quickly buckled under the pressure of the road. Both were flushed from office. The Grand Duke thanked his son, Hereditary Grand Duke Ludwig III. , in fact and died a few months later. Heinrich von Gagern became the new Prime Minister, but when he took over his duties in the National Assembly , he soon vacated his post. After just a few weeks, a de facto alliance between liberals and the old forces was formed when peasants and democrats tried to intervene in property rights. With the new electoral law of 1849, liberal-democratic state parliaments came into being twice in quick succession, which blocked the state budget. In autumn 1850 there was a "coup d'état from above", when the new strong man in the government, Reinhard Carl Friedrich von Dalwigk , had the new state parliament elect a drastically changed mode , which, however, greatly strengthened the property bourgeoisie, which therefore took part. Overall, the achievements of the revolution were only partially reversed.

Saxony

In the Kingdom of Saxony , in the course of the revolutionary events in March 1848, there was a change of minister and some liberal reforms . After the rejection of the imperial constitution, passed in Frankfurt on March 28, 1849, by the King of Saxony, the Dresden May uprising took place on May 3 .

The central figure in this survey of around 12,000 insurgents, including the then court conductor Richard Wagner , was the Russian anarchist Michail Bakunin . The aim of the uprising was the implementation of the imperial constitution ("imperial constitution campaign") and the achievement of democratic rights. The struggle of the radicals, organized in the March Associations, was aimed less at the recognition of the constitution itself than at the implementation and recognition of a Saxon republic in the imperial constitution.

The revolutionaries formed a provisional government after the king fled the city to Königstein fortress , the chambers were dissolved and the ministers resigned. Most of the Saxon troops were in Holstein. The fled Saxon government turned to Prussia for help. The Prussian troops, together with the remaining regular military units in Saxony, put down the riot on May 9, 1849 after bitter street fighting.

Holstein, Schleswig; first German-Danish war

At the end of March 1848 there was an uprising against the Danish king in the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein . This was preceded by a debate about the future of the absolutist , multi-ethnic Danish state as a whole . At that time, Schleswig and Holstein were ruled by the Danish king in personal union, with Schleswig being a fiefdom of Denmark under constitutional law , while Holstein was a fiefdom of the Roman-German Empire until 1806 and a member of the German Confederation after 1815. In terms of language and culture, Holstein was (Low) German-speaking, while German, Danish and North Frisian were widespread in Schleswig, with Danish and Frisian changing languages in favor of German in parts of Schleswig. Both German and Danish national liberals demanded basic rights and a free constitution and thus stood in opposition to conservative forces who wanted to maintain the paternalistic-conservative state as a whole. On the question of Schleswig's national ties, however, the two liberal groups opposed each other. After King Frederick VII had already submitted a draft for a moderate-liberal constitution for the entire state in January 1848, the two national groups came to a head in March 1848. While Danish national liberals called for the creation of a nation state including Schleswig, German national liberals called for the merger of the two duchies within the German Confederation. Both groups were thus in opposition to a multi-ethnic state as a whole. On March 22nd, in the course of the March Revolution, the so-called March Government was formed in Copenhagen . Two days later, a German-oriented provisional government was established in Kiel . Both governments were shaped by the dualism of liberal and conservative forces, but were irreconcilable at national level. The provisional government was recognized by the Bundestag in Frankfurt am Main before the opening of the Frankfurt National Assembly , but a formal admission of Schleswig into the Bund was avoided. The first German-Danish war then began. Prussian troops pushed forward on behalf of the federal government under General Field Marshal Friedrich von Wrangel to Jutland .

This approach led to diplomatic pressure on Prussia from Russia and England , who threatened to support Denmark militarily. Prussia gave in, and King Wilhelm IV concluded an armistice with Denmark on August 26, 1848 ( Armistice of Malmö ). This included the withdrawal of federal troops from Schleswig and Holstein and the dissolution of the provisional government in Kiel .

This unauthorized action by Prussia led to a crisis in the National Assembly that was now in session in Frankfurt. It became clear how insignificant the resources and influence of the National Assembly were. Ultimately, it was helplessly at the mercy of the powerful individual states of Prussia and Austria. Since the National Assembly had no means of power of its own to continue the war against Denmark without Prussia, it was forced to agree to the armistice on September 16, 1848. The consequence of this approval was renewed unrest all over Germany and especially in Frankfurt am Main (see September unrest ). Prussian and Austrian troops were then ordered to Frankfurt, against which there was barricade fighting on September 18. In these battles, the insurgents were no longer so concerned with the Schleswig-Holstein question, but increasingly with defending the revolution itself.

Frankfurt National Assembly

After Friedrich Daniel Bassermann had demanded representation at the German Bundestag in the Baden state assembly on February 12, 1848, this demand took on an extra-parliamentary life, the Heidelberg assembly on March 5 ended with the invitation to a pre-parliament as a constituent member. After the Bundestag had reacted on March 3 with the release of press freedom to the public pressure, he tried also in the field of constitutional and parliamentary representation sovereignty recover by admitting the need for a revision of the Federal Act and the establishment of a Siebzehnerausschusses to Development of a new constitutional basis for a united Germany. The pre-parliament, in which the liberals had the upper hand against the radical left, decided in the first days of April to work with the German Confederation and to jointly tackle the elections for a constituent national assembly in the interests of legalizing the movement. The Fifties Committee was set up to represent the revolutionary movement in relation to the Bundestag , and the Bundestag called on the states of the German Confederation to hold elections for the National Assembly. This met for the first time on May 18, 1848 in the Paulskirche in Frankfurt am Main and elected the moderate liberal Heinrich von Gagern as its president. The National Assembly set up a provisional central power as the executive, which took over state power from the Bundestag. At the head of the central power stood the Austrian Archduke Johann as Reich Administrator , Prince Karl zu Leiningen acted as Prime Minister of the newly created "Reich Ministry".

The Frankfurt National Assembly was supposed to prepare a nationally organized German unity and work out an all-German Reich constitution. In the National Assembly mainly the classes of the bourgeoisie were represented, men of property and education, high officials, professors , officers , judges , public prosecutors, lawyers , etc. Due to the accumulation of the upper bourgeoisie, the national assembly was sometimes derided by the people as the " dignitary parliament " or "Professors' Parliament" called. In fact, however, the parliament was more of a "civil servants" and "lawyers parliament" with a share of almost 50% each. In contrast, large landowners, farmers, entrepreneurs and craftsmen were hardly represented. Workers were not represented in the National Assembly at all. As part of the parliamentary work, different groups and parliamentary groups soon emerged, named after the places where they met after or between the meetings to coordinate their proposals and ideas. Apart from a large group of MPs who did not belong to the parliamentary groups, which were subject to displacements, there were essentially two ideological wings and two middle parties:

- The democratic left - in the parlance of the time also referred to as the whole , consisting of the factions Deutscher Hof , Donnersberg (far left), from November also the Nürnberger Hof - has been united under the umbrella of the Central March Association since the beginning of 1849 , from which above all the " Rump Parliament ”grew.

- The parliamentary-liberal left center - consisting of Württemberger Hof and Westendhall , from September also Augsburger Hof , from February 1849 united with the right center to form the “Weidenbusch” group.

- The constitutionally-liberal right center - shaped by the largest faction Casino , from August with the breakaway Landsberg - together with the left center they formed the liberal center , the so-called halves . In early 1849, part of the casino with the rights to the Paris court merged.

- The conservative right - mostly Protestant conservatives - first met in the Stone House , known as Café Milani from September onwards .

The performances of the groups ranged from the whole "represented a radical democratic " minority position of the establishment of a parliamentary all-German Democratic Republic, on one of the Half advocated constitutional monarchy with Erbkaisertum as so-called small German solution (excluding Austria) or as so-called Greater German solution (with Austria), up to the preservation of the status quo .

In addition to the paralyzing disagreement of the MPs, there was the lack of an executive branch capable of acting to enforce the resolutions of the parliament, which among other things. often failed because of Austrian or Prussian going it alone. This led to several crises , such as the Schleswig-Holstein question regarding a war against Denmark (→ above: Holstein, Schleswig; first Prussian-Danish war ).

In spite of everything, on March 28, 1849, with a majority of 42 votes, the Paulskirche constitution was passed, which provided for a small German solution under Prussian leadership. The King of Prussia was designated as emperor. When, on April 3, King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia refused the imperial dignity offered to him by the emperor's deputation (Friedrich Wilhelm described the imperial crown offered to him as “ripe baked from dirt and Latvians”), the Frankfurt National Assembly had in fact failed. Of the German medium-sized states, 29 approved the constitution . Austria, Bavaria, Prussia, Saxony and Hanover rejected them. The Prussian and Austrian MPs left the National Assembly when they were illegally recalled by their governments.

In order to still push through despite the growing strength of the counter-revolution, the constitution in the individual countries, it came in May 1849 in some revolution centers on the so-called Maiaufständen under the imperial constitution campaign . These uprisings formed a second, radicalized revolutionary surge, which in some areas of the federal government, such as Baden and Saxony, assumed civil war-like proportions. The Frankfurt National Assembly lost the majority of its members due to the recall and further resignations and moved to Stuttgart on May 30, 1849 as the " rump parliament " without the Prussian and Austrian MPs . On June 18, 1849, this rump parliament was forcibly dissolved by Württemberg troops. With the suppression of the last revolutionary struggles in Rastatt on July 23, the German Revolution of 1848/49 finally failed.

Effects and consequences in Germany

The suppression of the revolution and the victory of the reaction had created a specifically German dualism between the ideas of nation (→ patriotism , nationalism ) and democracy , which shaped the history of Germany in the long term and which is noticeable to the present day. Unlike in France , the United States and other countries, for example , where “nation” and “democracy” are traditionally seen as a unit after successful revolutions and a commitment to the nation usually also includes a commitment to democracy, that is a nation -Demokratie ratio in Germany still a matter polarizing - controversial and often very emotionally guided debates (→ German exceptionalism ).

After the failure of the revolution, a reactionary counter-revolution prevailed. In the period of the decade following 1848, known as the era of reaction , there was again a certain restoration of the old conditions, which, however, no longer assumed the dimensions of the Metternichian repression during the Vormärz .

The obvious failure of the nation-state goals of the revolution of 1848/49 often distracts our gaze from the lasting successes and sustainable advances that were achieved in the revolutionary years and which could not be revised by the victorious counter-revolution. In the first place, the final dissolution of the feudal order is usually mentioned . The demand for the abolition of hereditary subservience and the abolition of feudal burdens could be understood by large parts of the rural and peasant population as one of their own and led them to participate in the movements of March 1848. They gave the revolution the mass base and were thus decisive for the Responsible for the success of the March revolutions. The fear of the peasants' war and fear of social revolution had contributed significantly to the rapid retreat and relenting of those in power. The idea, according to which the peasants withdraw from the revolution after fulfilling their demands, thus depriving it of the mass base and thus becoming a reason for failure, was coined by the cultural scientist Wilhelm Heinrich Riehl , a contemporary of the revolution. It has been relativized in the more recent historiography: Everyday and cultural-historical research shows that the participation of rural parts of the population in the revolutionary events of 1848/1849 was far greater than was long wanted to admit. The imperial constitution campaign in particular was supported by broad mobilization in rural areas, including among peasant segments of the population.

Another lasting success of the revolutionary years was the abolition of the secret inquisition justice of the Restoration and Vormärz period. The demand for publicity of criminal justice, for public jury courts , was one of the fundamental March demands. Their enforcement led to a lasting improvement in legal certainty .

In addition, a more or less pluralistic press landscape emerged during the revolution after the press censorship was loosened . New newspapers influenced current political events from left to right. On the left, for example, it was the Neue Rheinische Zeitung published by Karl Marx , which was banned in 1849. The moderate center was represented by the Deutsche Zeitung , among others , while the right was represented by the Neue Preußische Zeitung ( Kreuzzeitung ) , which Otto von Bismarck was involved in founding . With the Kladderadatsch , one of the first important satirical magazines in Germany was launched on May 7, 1848 .

The national idea of a small German unification (→ Union policy ) was - after its temporary failure in the Olomouc punctuation in 1850 - finally by the ruling conservative forces under Prussian leadership, especially under Otto von Bismarck as Prussian Prime Minister since 1862, after the three " German wars of unification " Prussia against Denmark , against Austria and against France implemented and implemented from above. In 1871, after the victory over France, a German Empire with King Wilhelm I of Prussia was proclaimed German Emperor .