Neue Preussische Zeitung (Kreuzzeitung)

The Kreuzzeitung was a national daily newspaper in the Kingdom of Prussia and later the German Empire from 1848 to 1939 . It appeared from 1848 with twelve issues a week (one morning and one evening issue daily except Mondays) and from 1929 with seven issues a week (daily). The newspaper had editorial offices in various cities at home and abroad. The head office was originally located at Dessauer Strasse 5, from 1868 at Königgrätzer Strasse 15 and from 1927 at Dessauer Strasse 6-8 in Berlin .

With the Iron Cross as an emblem in the title, it was initially officially called Neue Preußische Zeitung , although it was simply called the Kreuzzeitung in general and also in official usage . In 1911 the name was changed to Neue Preußische (Kreuz-) Zeitung and from 1929 to Neue Preußische Kreuz-Zeitung . From 1932 to 1939 the official title was only Kreuzzeitung.

The paper was a trend-setting organ of the conservative upper class. The readership included the nobility, officers, high officials, industrialists and diplomats - but never more than 10,000 subscribers . Because the readers were among the elite , the Kreuzzeitung was often quoted and was at times very influential. From the first to the last edition, the newspaper used the German motto of the Wars of Liberation as a subtitle : “Forward with God for King and Fatherland”.

Emergence

In the Kingdom of Prussia, the Allgemeine Prussische Staatszeitung appeared as the official gazette from 1819 , from which the German Reichsanzeiger and today's Federal Gazette later developed. Another newspaper, which particularly represented the interests of the Prussian upper class, did not exist. In response to the March events , the then Bundestag repealed the Karlovy Vary resolutions on April 2, 1848 . The bourgeoisie in particular, but also radical left forces, used the newly won freedom of the press and founded numerous newspapers. Examples include the National-Zeitung with bourgeois-liberal aspects or the Neue Rheinische Zeitung with radical-communist content.

Monarchist- conservative circles forced the establishment of their own newspaper as an antipole; this became the Kreuzzeitung . Originally it was supposed to be called "The Iron Cross" , which some of the founding fathers found too militaristic. They agreed on the non-binding name "Neue Preußische Zeitung" with an illustration of the Iron Cross in the lettering. The newspaper was named Kreuzzeitung by the authors, creators and readers from the very first issue . The main initiators were:

- Ernst Ludwig von Gerlach ,

- Leopold von Gerlach ,

- Hans Hugo von Kleist-Retzow ,

- Ernst Karl Wilhelm Adolf Freiherr Senfft von Pilsach ,

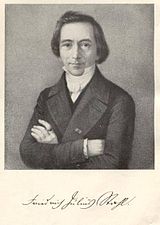

- Friedrich Julius Stahl ,

- Hermann Wagener ,

- Moritz August von Bethmann-Hollweg ,

- Otto von Bismarck

- Carl von Voss book

Almost all of them belonged to the camarilla around Friedrich Wilhelm IV. The introduction of the newspaper and the establishment of the publishing house were prepared according to general staff. Good networking in the highest state institutions should be characteristic. To this end, the founding fathers met at the “Zum Schwarzen Bären” inn in Potsdam . Berlin was chosen as the printing location and seat of the “Neue Preußische Zeitung AG”. The calculated starting capital of 20,000 thalers was achieved by selling shares of 100 thalers each. A total of 80 people drew, including Bismarck, who then wrote articles for the Kreuzzeitung personally for a long time. Carl von Voss-Buch is the largest shareholder with shares worth 2,000 thalers. The subscription price was set at 1.5 thalers per quarter, outside of Berlin the purchase costs were 2 thalers due to the postage surcharge. The sheet was initially to be printed by the Brandis company at Dessauerstrasse 5 in Berlin. From mid-June 1848, three trial newspapers were sent out. This enabled a large number of subscriptions to be sold to aristocrats, district administrators and higher officials right away. The editor-in-chief was taken over by Hermann Wagener, so that on June 30, 1848 the regular "number 1" of the Neue Preußische Zeitung could appear.

According to its new organ , the Prussian Conservative Party was also called the Kreuzzeitungspartei or "Kreuzpartei". Likewise, the colloquial terms “black” or “black disposition” for members and voters of Christian-conservative parties go back to the Kreuzzeitung; because the sheet was printed in jet black ( RAL 9005 ) until its end .

Development up to the establishment of an empire

The Kreuzzeitung was controversial from the start, even among the various conservative groups. Particularly at the beginning of the era of reaction , a section of the high nobility “categorically rejected such democratic weapons for forming opinions”. However, Wagener was able to gain the trust of the initiators very quickly. With the support of Friedrich Julius Stahl, he built up a dense network of authors and informants within a very short time. The majority wrote their articles under a pseudonym as freelance workers. Correspondents were only permanently employed in Vienna, Dresden, Munich and other capitals of the individual German states . For a long time Bismarck personally supplied reports from Paris to the newspaper. The reporters got news from all other countries from the diplomats in Berlin.

The editorial team was relatively independent. Whereby the newspaper's loyalty to the monarchy was never questioned. Until the end of 1849, the sheet was not yet self-supporting. Friedrich Wilhelm IV. Is said to have personally supported the Kreuzzeitung financially at this time. Nevertheless, the editorial team was soon able to buy back most of the shares from the donors. The respective editor-in-chief will take over the chairmanship of the stock corporation. The shareholders were only represented in a five-person committee , which had the right to check the bookkeeping , but was unable to influence the newspaper's content or personnel.

The first editor-in-chief was already clearly aware that this independence had clear limits. After the newspaper permanently and undisguised the person and dictatorship of Napoleon III. criticized, Bismarck urged the paper to exercise restraint. The editors ignored the information. Consequence: In April 1852, the Kreuzzeitung was banned in France , and several editions were also confiscated in Berlin. The next tensions followed when the editors openly spoke out against the abolition of the basic rights of the German people and thus against the small German solution . This is where the most diverse power interests and spheres of influence met.

The newspaper's position repeatedly met with resistance from the then Prussian Prime Minister Otto Theodor von Manteuffel , a declared opponent of the Kreuzzeitung. Another bitter rival of the paper was the head of the police department in the Ministry of the Interior, Karl Ludwig Friedrich von Hinckeldey . This startled not afraid, the editor of the new Prussian newspaper for several days in detention to lock when he refused to name the share of all writers together with anonymous authors of the Police Department. Hinckeldey received a personal reprimand from the king for his unauthorized action. Although Wagener was backed by this, he resigned from office with the Kreuzzeitung, exasperated. Tuiscon Beutner became the new editor-in-chief in 1854. Friedrich Wilhelm IV. Gave him on the way "that the newspaper should appear undeterred and nothing to change in its policy, only should be careful about France".

Even under Beutner's leadership, the paper was not immune to confiscation . Printed editions have repeatedly been completely confiscated . The reasons for this were the different views of the Conservative Party, which ultimately led to several splits from 1857 onwards. The relationship between the Kreuzzeitung and Bismarck also developed negatively. On the one hand, he had his press employee Moritz Busch regularly write articles for the Kreuzzeitung until 1871, on the other hand, the Norddeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung continually developed into “Bismarck's house postil”.

Although the Kreuzzeitung predominantly represented the views of the arch-conservatives, ergo the representatives of the king and later the emperor, it also always described the interests of the liberal-conservative, Christian-conservative and socially-conservative forces. The paper presented a fact or an action primarily as a report or message . But just the fact that she published different positions without comment, brought her regular criticism. The German question and the relations between the German states and the major European powers developed into constant controversial issues .

The Kreuzzeitung received most of the information from younger diplomats . The first foreign correspondents were George Ezekiel for Paris and from 1851 Theodor Fontane for London. Later the Kreuzzeitung had permanent employees in all European capitals. Until then, reports from foreign newspapers were sometimes taken over and issued as separate works. What violates copyright law today was a widespread custom back then, not only among German newspaper writers. Even the Times translated entire articles in the Kreuzzeitung and without hesitation cited “own Berlin-Correspondent” as the source .

Fontane worked in London not only for the Neue Preussische Zeitung . For a time he was directly subordinate to the German ambassador Albrecht von Bernstorff and launched press reports in support of Prussian foreign policy in English and German newspapers. At the same time he traveled to Copenhagen , from where he regularly wrote articles about the German-Danish War for the Kreuzzeitung. In his life reports, Fontane stated that he “did not find any Byzantinism or grumbling at the Kreuzzeitung” and that Friedrich Julius Stahl's motto was:

"Gentlemen, let's not forget, even the most conservative paper is still more of a paper than conservative."

This meant that the sales success of a newspaper always includes the presentation of different opinions, which should generally be reproduced without any judgment on the author. In 1870 Fontane switched to the Vossische Zeitung as a theater critic .

The newspaper was printed from 1852 to 1908 at the Heinicke'schen Buchdruckerei in Berlin. The publisher Ferdinand Heinicke also took over responsibility for the content of the paper as the so-called seat editor . In this way, the Kreuzzeitung protected its editors from legal disputes and lawsuits.

Trends during the Imperial Era

In 1861 the circulation was 7,100 and increased to around 9,500 by 1874. Despite the relatively small circulation, it stood at the interface between politics and journalism and at the height of its power. Almost all newspapers at home and abroad regularly used introductory sentences such as "According to information from the Kreuzzeitung ...", "Well-informed circles of the Kreuzzeitung have learned ...", "As the Kreuzzeitung reports ..." etc. After the establishment of the Reich , the reputation of the newspaper changed permanently. The reasons for this were the so-called "era articles", the "Hammerstein affair", but above all the dissolution of the Prussian Conservative Party. This split into the following among others:

- Free Conservative Party

- German Progressive Party

- National Liberal Party

- German Center Party

- Christian Social Party

- German Conservative Party

From 1868 Bismarck used the notorious reptile fund to influence the press and implement his policies. There is evidence that the Neue Preußische Zeitung received no funds from the “black coffers”. The editors even dared to question these propaganda methods in two articles . As a stock corporation, economically self-sustaining, the Kreuzzeitung was in principle independent of the crown and government. Likewise, it has never been a party newspaper or the “mouthpiece” of a particular party. Until the last issue in 1939, the paper had no party affiliation. Rather, the Kreuzzeitung represented the link between all conservative forces.

The "era articles"

In autumn 1872 Philipp von Nathusius-Ludom took over the editor-in-chief. He had no journalistic qualifications, but tried hard to make the paper populist for readers - in today's parlance - and to unleash controversy. His endeavors ended ominously.

In June and July 1875 the journalist Franz Perrot published the five-part series of articles under a pseudonym in the Kreuzzeitung: "The era of Bleichröder - Delbrück - Camphausen and the new German economic policy". In it he attacked Bismarck indirectly in the person of his banker Gerson von Bleichröder. In the articles heavily edited by Nathusius-Ludom, Bismarck's economic policy was described as the cause of the founders' row , the bankers were accused of selfish speculation and Bismarck was accused of corruption with little concealment .

The articles sparked a scandal . Perrot revealed that bankers, noblemen and members of parliament could not only gain advantages on the stock exchange through diplomatic channels . It came to light that several civil servants engaged in wild speculation and used their official or political influence in personal participation and the formation of public companies. Bismarck had to comment on the allegations in court and before the Reichstag . For him, the conflict with the Kreuzzeitung was "now flagrant and the tablecloth cut up". Bismarck publicly called for a boycott of the Kreuzzeitung newspaper. The countered by publishing over 100 names of declarants , noblemen, members of parliament and pastors who expressed their consent to the publication of the research in letters to the newspaper.

Nothing could be proven to the Chancellor; but in fact he had hoped that his economic policies would split the Liberals . In addition, his policies did contribute to momentous fluctuations on the stock market. For example, he bought up private railways himself or through middlemen in order to establish a kind of state railroad system, and thus put the railways corporation and their steel suppliers under considerable pressure. Perrot's allegations of corruption also later turned out to be correct. The documents found showed that Bismarck had, among other things, participated in the establishment of the Boden-Credit-Bank with his own funds , whose deed of foundation and articles of association had been personally signed and thus given it a privileged position among the German mortgage banks. The “Iron Chancellor” has never forgiven the Kreuzzeitung for the “era articles”. Even in his old work, Thoughts and Memories , he spoke of “poisoning” and the “vulgar Kreuzzeitung”.

Who Perrot's source was could never be known. It was speculated whether Wilhelm I wanted to personally give his Chancellor a lesson. Outwardly, the emperor did not comment on the allegations of corruption; however, he disliked the anti-Jewish polemics contained in the five articles. The aim of the article was not primarily to defame the Jews. The stated aim was to "annoy Bismarck with illness". The representative attacks on the Jewish bankers went too far for Wilhelm I, who advocated the integration of the Jews , signed an all-German state law on equal rights for Jews in 1871 and in 1872 raised Gerson Bleichröder as the first Jew to hereditary nobility . Consequence: Franz Perrot and Philipp von Nathusius-Ludom had to leave the Kreuzzeitung.

The "Hammerstein Affair"

Benno von Niebelschütz became the new editor-in-chief in 1876 . With him, according to the Emperor, the newspaper lost "not only every journalistic bite, but in some cases even its legibility". He was followed in 1884 by Wilhelm Joachim Baron von Hammerstein . Under his leadership, the paper dealt with the so-called Jewish question as an independent topic. From today's perspective, the Kreuzzeitung came close to anti-Semitic publications at times. The term “ anti-Semitic ” did not exist in Germany before 1879 and the controversy was fueled by various supporters and opponents from all possible directions. Even among the Jewish associations there were contradicting tendencies which, on the one hand, advocated a turn to modern society and strong assimilation , and , on the other hand, sought to preserve the traditions of the faith. At the latest with Theodor Herzl , who sought the establishment of a Jewish state with publicity, the debate took on foreign policy dimensions. In the last two decades of the 19th century, the topic was so prominent that no newspaper could get around it.

Hammerstein worked closely with the court preacher Adolf Stoecker , with whom he maintained a personal friendship. Stoecker demanded, also in articles of the Kreuzzeitung, the restriction of the constitutional equality of the Jews that took place in 1871 and an unconditional assimilation in the form of baptism . He also accused several people of abusing Jewish emancipation to secure positions of economic and political power. Hammerstein and Stoecker ignored the warnings from the Crown Prince and shortly afterwards Emperor Friedrich III. completely, who repeatedly referred to hostility towards Jews as the “shame of the century”. The imperial family was determined to put an end to Stoecker's work. In the spring of 1889 the Privy Council officially informed him that he had to stop his agitation. Because Stoecker continued to rush, he was forced to resign a year later by Wilhelm II , who became emperor after the early death of his father.

In fact, the Jews were an integral part of the German Empire. Jewish authors have also worked for the Kreuzzeitung since it was founded. Around 1880 she employed 46 permanent Jewish correspondents and several Jewish freelancers. In the conservative parties there were Jewish MPs with a large Jewish electorate. The reproach by the emperor had its effect. For example, in 1890 the Kreuzzeitung did not take part in the Vering – Salomon duel , which was controversially discussed in the media , but dealt with the disputes objectively. The paper followed a self-developed "taming concept" which it outlined in the summer of 1892 with the words: "The Kreuzzeitung is there to keep anti-Semitism within limits."

However, editor-in-chief Hammerstein himself did the greatest damage to the Kreuzzeitung in terms of seriousness and credibility. Hammerstein, who liked to portray himself as a “clean man”, always full-bodied campaigning for law and order , cultivated co-marital relationships and lived on a very large scale, was dismissed from the Kreuzzeitung's committee on July 4, 1895 for dishonesty. Background: In his role as editor-in-chief, he approached a paper supplier named Flinsch and suggested a deal to him. He asked for 200,000 marks (equivalent to around 1.3 million euros today) and in return undertook to buy all the paper for the Kreuzzeitung from Flinsch for the next ten years. The deal came about. Hammerstein had extremely inflated bills issued and put the difference in his own pocket. To do this, he forged the signatures of the supervisory board members Georg Graf von Kanitz and Hans Graf Finck von Finckenstein, as well as the seal and signature of a head of office . The matter was exposed. When it came to light that Hammerstein had used up a pension fund set up by the Kreuzzeitung , he resigned his mandates in the Reich and Landtag in the summer of 1895 and fled with the 200,000 marks via Tyrol and Naples to Greece.

The scandal caused quite a stir and was debated several times in the Reichstag . The competition from Kreuzzeitung - and it was great - brought the story to the front pages and reported almost daily on the status of the investigation. In the search for the criminal editor-in-chief, the Reich Justice Office finally sent a criminal superintendent Wolff to southern Europe. He roamed several countries and found Baron von Hammerstein alias “Dr. Heckert ”on December 27, 1895 in Athens . Wolff led via the German embassy whose designation and left him on arrival in Brindisi arrest. In April 1896 Hammerstein was sentenced to three years in prison.

In the course of these events, the Neue Preußische Zeitung lost around 2,000 readers. The circulation fell steadily. Even Wilhelm II couldn't change that, who refused to drop the paper and had it publicly announced: "The Kaiser reads the Kreuzzeitung as before, it is even the only political newspaper he reads."

Neutrality in the First World War

The decline was only stopped by Georg Foertsch , who took over as editor-in-chief in 1913 and kept the circulation constant at 7,200 copies until 1932. The major a. D. previously worked for the Imperial Navy as a press attaché. He maintained neutrality and concentrated on the Kreuzzeitung's core competence, international reporting. Foertsch promoted young journalists, but only hired professionals. These had excellent connections to diplomats, politicians, industrialists at home and abroad, so that the Kreuzzeitung was able to publish numerous reports exclusively and / or as the first. Domestically, he maintained personal contacts with the Reich Treasury , from where Foertsch regularly received comprehensive information on the current financial and economic situation and the plans of the German Reich.

The new editor-in-chief reorganized the finances and combined the buildings and editorial offices that the newspaper had acquired in recent decades, which the newspaper owned at home and abroad, into a wholly-owned subsidiary , Kreuzzeitung Immobilien AG . He also increased the subscription price to 9 marks (around 55 euros today) per quarter. The readership obviously had no problem with that. Noble landowners, politicians and high officials in particular received the paper for an additional 1.25 Marks per week (around 8 euros today) with two daily deliveries by the Reichspost . In the German protected areas as well as Austria-Hungary and Luxembourg, the postage fee was also 1.25 marks per week. The single number cost 10 pfennigs.

One of his best foreign experts was Theodor Schiemann . He attracted Wilhelm II's attention through his books and political articles in the Kreuzzeitung. This resulted in a friendly relationship through which Schiemann, as an advisor, was able to exert political influence, especially on Eastern European issues. On the eve of the First World War , Schiemann foresaw a two- front war and published on May 27, 1914 in the Kreuzzeitung: “The German Reich has to reckon with the fact that it will find England on the side of its future opponents, and not negligently such a conflict The article had no effect: On August 7, 1914, the Kreuzzeitung published Kaiser Wilhelm's well-known speech “To the German People!” that “now the sword must decide”.

During the First World War, not only did all parties enter into the so-called truce , but also basically all German newspapers. This went so far that several conservative parties effectively ceased their activities. During this time , the Kreuzzeitung delivered well-researched leading articles , which are still one of the most important sources for historians on military and daily political events of the First World War.

On November 9, 1918, the headline of the Kreuzzeitung with the headline "The Kaiser thanks!"

“We have no words to express what moves us at this hour. The thirty-year reign of our emperor, who always wanted the best for his people, ended under the force of events. The heart of every monarchist cramps at this event. "

Deep sadness, apathy , escapism and hopelessness as well as fears of what was to come and even panic reactions characterized the prevailing mood of the old elites after the collapse of the German Empire. For the old royal Kreuzzeitung a world has irrevocably collapsed.

Situation in the Weimar Republic

In the literature, the attitude of the editors and thus the basic political direction of the Kreuzzeitung are interpreted differently, especially during the Weimar period . Depending on the ideological view of the author, the spectrum ranges from “stick Protestant”, “feudal”, “German national”, “ultra-conservative”, “agricultural”, “East Elbian”, “Junky-conservative” to “anti-modern”. More recent research uses “monarchist-conservative” as an umbrella term and regards other descriptions at least as one-sided, some of them as incorrect. As early as November 12, 1918, the Kreuzzeitung ran the headline: “Germany is facing an upheaval as history has never seen it before” and, true to Aristotle's constitutional doctrine, called democracy a “degenerate” form of government, “only tyranny is worse”. The goal of the paper remained the same: the defense of the monarchy. That is, the attitude of the Kreuzzeitung was directed against the Weimar Republic, but also against a dictatorship.

Politically, most of the employees of the Kreuzzeitung did n't feel at home anywhere after the November Revolution. Few of the editors turned their backs on the paper; almost all of them were monarchists. They received some of the highest wages in the industry, especially on time. The Kreuzzeitung was not affiliated with parties, so that the correspondents had a relatively large amount of leeway. As before, most of the newspaper consisted of uncommented foreign news, which had to be researched carefully. Travel expenses were reimbursed as well as " cover bills ". The Kreuzzeitung gave employees access to the highest circles at home and abroad. Due to its relationship to politics and business, the Kreuzzeitung was still regarded by journalists as a cadre forge. The world stage , for which the opponent was everything that was called the old German leadership, certified the "old royalist Kreuzzeitung useful foreign policy information" and liked to employ journalists like Lothar Persius , who had learned their trade at the Neue Preussische Zeitung . And even the forward apparently had no qualms about hiring people like Hans Leuss , who had to leave the Kreuzzeitung because of his anti-Jewish agitation.

Jewish editors continued to work for the Kreuzzeitung. The paper deliberately stood out from the “radical anti-Semitism” of the Hugenberg press . In principle, the newspaper cannot be called Jewish-friendly, but neither can it be called anti-Semitic. The personalities of the respective editors shaped the political tendencies of the paper. Some authors almost naturally used the colloquial expressions of the time such as "Judas wages", "Judas kiss" or "Judas politics". However, non-Jewish politicians were also defamed as " Judas ", who was considered a symbol of a traitor. The editors were stunned by the repositioning of some conservative parties. For example, the center had transformed from a Catholic-conservative party into a Christian-democratic people's party and was capable of forming coalitions with all political groups until the end of the Weimar Republic. From now on, the Kreuzzeitung did not primarily denigrate communists or socialists, but the politicians of the center. Their denomination basically played no role. The paper described the Catholic center politician Matthias Erzberger as a “spoiler” and “fulfillment politician”, as did the Catholic center deputies Heinrich Brauns or Joseph Wirth , all of whom a year earlier had expressly identified with Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg's truce policy.

As early as November 17, 1919, Georg Foertsch attacked “massively republican Reich ministers” in an article. In the memoir he published that the forces against “this corrupted revolutionary government are gaining ground every day” and concluded with the declaration of war: “We or the others. That is the watchword! ”The new Reich government then filed a criminal complaint . Foertsch received a fine of 300 marks for insulting . In mitigating the sentence, the court took into account "that the Kreuzzeitung in principle represents a standpoint opposing the Reich government and that the author thought and wrote into an irritated mood against the Reich government".

Political Direction

The paper particularly strengthened the conservative Bavarian People's Party (BVP), which split off from the German Center Party after the so-called Erzberger reforms and was the most elected party in Bavaria in all state elections up to 1932 . The BVP opposed republican centralism and initially openly demanded secession from the German Reich. Journalistic support was provided by Erwein von Aretin , editor-in-chief of Münchner Neuesten Nachrichten , who was also on the supervisory board of the Kreuzzeitung. He belonged to the top management of the monarchists in Bavaria and also spoke openly for a separation of the Free State from the Reich and the proclamation of the monarchy.

The Kreuzzeitung also supported the monarchist wing of the German National People's Party (DNVP) led by Kuno von Westarp . This was at times seen as the most suitable party for implementing one's own convictions. This included the rejection of the republic in its status quo, the Treaty of Versailles and the reparations claims of the victorious powers. However, a basic Christian attitude always played a decisive role. Alfred Hugenberg's policy of rapprochement with the NSDAP met with criticism from the editor-in-chief and on the supervisory board of the Kreuzzeitung. Specifically, they rejected the exaggerated Germanism of the German Nationals as well as National Socialism in principle. The Kreuzzeitung openly castigated the “primitive Germanic fantasies” and the “new communist terrorist actions of the National Socialist Party”. She accused the NSDAP not only of “betraying the thought of the nation”; she repeatedly described how "millions of Germans fall into the brown pied piper". Ultimately, the editor-in-chief emphasized in a large article on December 5, 1929 that the Kreuzzeitung was not the “mouthpiece of the DNVP” and “not at all a German national party organ”.

The Kreuzzeitung also only supported the Stahlhelm to a limited extent in the person of Theodor Duesterberg , whom the National Socialists discredited because of his “not purely Aryan origin”. In Duesterberg's candidacy during the Reich presidential election in 1932, a steel helmet was shown above the Iron Cross in the headline of the newspaper, but this was only a means to an end. Editor-in-chief Foertsch repeatedly exposed the NSDAP's election campaign methods, also claimed that “Hitler was not free from socialist ways of thinking and therefore a danger to Germany”, and again headlined with sentences like: “May the day come when the black again -White-red flag is blowing on the government buildings. "

The Stahlhelm had over 500,000 and the DNVP almost a million members. Both groups had their own party newspapers. These members never belonged to the target group of the Kreuzzeitung, whose circulation was constant at 7,200 until 1932. At no time did the sheet become the property of Stahlhelm or the DNVP. Franz Seldte , the federal leader of the steel helmet, owned the Frundsberg Verlag in Berlin, through which he distributed several publications for the steel helmet. Alfred Hugenberg owned over 1,600 German newspapers, so that he never needed the Kreuzzeitung as a “mouthpiece” or party newspaper, but wanted to take it over for reasons of prestige. The target group of the Kreuzzeitung always remained the conservative upper class. This included the members of the German Men's Club . All members of the supervisory board of the Kreuzzeitung and Georg Foertsch as editor-in-chief were also represented. Many of the approximately 5,000 members of the men's club were readers of the Kreuzzeitung, provided information and provided financial aid to the newspaper during the years of inflation.

Paul von Hindenburg received unreserved support from the Kreuzzeitung, who was regarded as the guarantor and sole personality for the restoration of the monarchy. Hindenburg, too, occasionally passed internal information to the paper and wrote short articles himself, which he had published about Kuno von Westarp in the Kreuzzeitung. An interview with the Berliner Tageblatt , which came about at the request of the Reich President's press department, is legendary . Hindenburg reluctantly agreed to the conversation, said he grabbed one of those fatal world newspapers for the first time in his life and said in a defiant tone to his press officer: “But I will only continue to read the Kreuzzeitung.” Accordingly, the interview with Theodor Wolff was slow . Right at the beginning, Hindenburg replied to the question of whether he knew the Berliner Tageblatt : "I've been used to reading the Kreuzzeitung for breakfast all my life." The rest of the conversation didn't get any better because Hindenburg spoke to Wolff, the most influential representative of the Mosse-Presse risked talking neither about hunting nor about the military.

For the Kreuzzeitung, Hindenburg remained the bearer of hope until shortly before January 30, 1933, showing little inclination to transfer the office of Chancellor to Hitler. On August 12, 1932, he publicly rejected Hitler's demand “to transfer the leadership of the Reich government and the entire state authority to him in full”. The Kreuzzeitung praised Hindenburg's attitude towards Hitler as "understandable and well-founded". Approval of Hitler's demands, according to the newspaper, would have degraded the Reich President to a "puppet that is staged at ceremonial acts dressed in state robes". With this assessment, the Kreuzzeitung designed exactly the scenario which, after the seizure of power should be true of Hitler.

Economic collapse

In the course of hyperinflation in 1922/23 , the Kreuzzeitung ran into existential difficulties financially. She continuously lost her reserves and all real estate. Foertsch managed to keep the business going through private donations from members of the gentleman's club. In order to prevent a takeover by the Hugenberg Group, in September 1926 he agreed an interest group with Helmut Rauschenbusch , who was also a member of the gentlemen's club and publisher of the German daily newspaper . To do this, they founded the Berliner Zentraldruckerei GmbH , in which the Kreuzzeitung and the German daily newspaper were printed from January 1927. Although some employees, such as the journalist Joachim Nehring , provided articles for both papers in the future, the editorial offices of the Kreuzzeitung and the German daily newspaper remained self-sufficient.

The edition of March 1, 1929 brought about a major change. The Neue Preußische (Kreuz-) Zeitung officially became the Neue Prussische Kreuzzeitung . The editors presented this to the readers as follows:

“From today our paper will appear in a different guise. The following consideration was decisive for the change in our headline: Our newspaper, founded under the name 'Neue Preußische Zeitung' in 1848, was soon widely publicly named after its landmark, the Iron Cross, or simply 'Kreuzzeitung'. Even today, our paper is known almost exclusively by this name at home and abroad. Likewise, in political terms the word 'Kreuzzeitung' has been a fixed term for decades, which has its basis in the Iron Cross with its legend ' With God for King and Fatherland '. Indeed, for Christian-conservative thinking and working, this cross with its accompanying words is an established symbol for which we fight, now as it was before. We remain true to our great tradition, which has its roots in Prussia and the Prussian kingdom. "

But not only the name was changed. For reasons of economy, the paper will now only appear once a day instead of twice a day, but now also on Mondays. An increase in circulation could not be achieved. Around this time, around 4,700 different daily and weekly newspapers were published throughout the Reich. Never before and since have there been more newspapers in Germany. Smaller and “independent” publishers were subject to enormous competitive pressure. Mergers took place almost weekly. With the beginning of the global economic crisis , the Kreuzzeitung faced bankruptcy and was incorporated as a wholly-owned subsidiary into the Deutsche Tageszeitung Druckerei und Verlags AG . As a representative of the Kreuzzeitung, Kuno von Westarp moved to the supervisory board. At the same time, the company took over the Deutsche Schriftenverlag , in which, among other things, the central organ The Stahlhelm , which was distributed by Franz Seldte, appeared. In this way, Seldte entered the supervisory board of the Deutsche Tageszeitung Druckerei und Verlags AG , but left the company together with Westarp in 1932.

In terms of circulation and content, nothing changed for the Kreuzzeitung. Their intended readership remained unchanged: the nobility, large landowners, industrialists, senior officers and civil servants. Foertsch and Rauschenbusch got along very well, so that from now on two daily newspapers for an identical target group were produced by the same publisher. Both the Kreuzzeitung and the Deutsche Tageszeitung kept their individual departments and editors-in-chief. In the spring of 1932, the Kreuzzeitung hit another blow. On April 3, 1932, she had to report in a large advertisement that her “Editor-in-Chief Major a. D. Georg Foertsch died suddenly and unexpectedly at the age of 60 on the night of April 2nd, after he had done his editorial work the day before as usual until the evening hours. "The Weltbühne headlined:" Kreuz-Zeitung (†) : A reptile perishes and dies the well-deserved national death. ”This did not mean the death of Georg Foertsch per se, but rather that through his death the newspaper became leaderless and would inevitably perish due to the various actors and spheres of interest.

This assessment was true. On May 2, 1932, Kuno von Westarp renounced the rights to which he was entitled and resigned from his supervisory board post. This meant that the Kreuzzeitung was only a brand of the Deutsche Tageszeitung Druckerei und Verlag AG . Franz Seldte also left the publishing house in 1932. Westarp and Seldte recognized that Franz von Papen's plans to integrate, curb and dominate the National Socialists within a monarchist-conservative government could no longer be realized. This also made the Kreuzzeitung obsolete. As was to be expected, after the Reichstag election in June 1932, the circulation fell to 5,000 copies. Above all officials now orientated themselves in the direction of Völkischer Beobachter .

time of the nationalsocialism

On September 18, 1932, the paper was officially renamed to (only) Kreuzzeitung . On the same day, Hans Elze, Georg Foertsch's "right hand man", took over the orphaned chair of the chief editor. On January 16, 1933, the German newspaper Druckerei und Verlag AG changed its name to Deutsche Zentraldruckerei AG . The corporation remained under the leadership of Helmut Rauschenbusch.

After the freedom of the press had already been restricted by emergency ordinances in the Weimar Republic , the ordinance of the Reich President for the protection of people and state came into force on February 28, 1933 . In this way, the basic right to freedom of expression and freedom of the press was abolished and the distribution of “incorrect news” was prohibited. What was right and what was wrong will in future be determined by the Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda . On April 30, 1933, the Reich Association of the German Press approved the synchronization . In this episode, Elze left the Kreuzzeitung on August 2, 1933, because he “did not want to be dictated what and what should be reported”. In addition, a regulation now stipulated that each owner was only allowed to be involved in one daily newspaper and that publishers with more than one daily newspaper were to be expropriated. Rauschenbusch decided in favor of the Kreuzzeitung. The last edition of the Deutsche Tageszeitung appeared on April 30, 1934 ; and that although it had a significantly higher circulation than the Kreuzzeitung. However, Rauschenbusch was no longer able to influence the content of the Kreuzzeitung. In order to be able to enforce a control of the content, the editors-in-chief were appointed from 1935 by the Reich Press Chamber. They were no longer subordinate to the publishers, but made their editorial decisions based on the instructions of the Propaganda Ministry.

After a large number of changes in the editorial team and its management, the remaining recipients of the newspaper knew by the summer of 1937 at the latest that the days of the Kreuzzeitung were numbered. Until then, the National Socialists had shown a certain consideration for the old-conservative readers of the traditional paper. The grace period ended on August 29, 1937. The front page read: "As of today we have taken over the Kreuzzeitung". On that day, Joseph Goebbels appointed the convinced National Socialist Erich Schwarzer as the new editor-in-chief and integrated the Kreuzzeitung into the Deutsche Verlag together with other bourgeois-conservative media . At this point in time, the editors of the Kreuzzeitung had still delivered some reports worth reading, for example Hans Georg von Studnitz , who interviewed Gandhi and Nehru during a six-month stay in India in 1937 . The old members of the editorial team reacted to the new tones that Erich Schwarzer struck, partly with resignation, partly with a kind of service according to regulations .

The last editor-in-chief was Eugen Mündler in May 1938 . The Kreuzzeitung - or what was left of it - appeared under his direction with the text of the Berliner Tageblatt . Readers received the last edition of the Kreuzzeitung on January 31, 1939. After 91 years, a piece of German press history ended .

Editors-in-chief

- 1848–1854 Hermann Wagener

- 1854–1872 Tuiscon Beutner

- 1872–1876 Philipp von Nathusius-Ludom

- 1876–1884 Benno von Niebelschütz

- 1884–1895 Wilhelm Joachim von Hammerstein

- 1895–1906 Hermann Kropatscheck

- 1906–1910 Justus Hermes

- 1910–1913 Theodor Müller-Fürer

- 1913–1932 Georg Foertsch

- 1932–1933 Hans Elze

- 1933 Rudolf Kötter

- 1934–1935 Rüdiger Robert Beer

- 1935–1937 Fritz Chlodwig Lange

- 1937–1938 Erich Schwarzer

- 1938–1939 Eugen Mündler

Well-known authors (selection)

- Alexander Andrae , pseudonym: Andrae-Roman

- Berthold Auerbach

- Julius Bachem

- Theodor Fontane

- Hermann Ottomar Friedrich Goedsche , pseudonym: Sir John Retcliffe

- Wilhelm Conrad Gomoll

- Siegfried Hirsch

- George Ezekiel

- Otto Hoetzsch

- Helene von Krause , pseudonym: C. v. Bright

- Hans Leuss

- Marx Möller

- Joachim Nehring

- Lothar Persius , fleet expert

- Julius Rodenberg

- Justus Scheibert , war correspondent

- Louis Schneider , Russia correspondent

- Gustav Schlosser

- Klaus-Peter Schulz

- Franz-Josef Sontag , pseudonym: Junius Alter

- Adolf Stein

- Hans Stelter

- Louise zu Stolberg , under a pseudonym

- Rudolph Stratz , theater critic

- Hans Georg von Studnitz , Asia correspondent

- Alexander von Ungern-Sternberg , pseudonym: Sylvan

literature

- Bernhard Studt: Bismarck as an employee of the "Kreuzzeitung" in the years 1848 and 1849. J. Kröger, Blankenese 1903.

- Hans Leuss: Wilhelm Freiherr von Hammerstein. 1881–1895 editor-in-chief of the Kreuzzeitung. On the basis of letters and notes left behind. Walther, Berlin 1905.

- Luise Berg-Ehlers: Theodor Fontane and the literary criticism. On the reception of an author in the contemporary conservative and liberal Berlin daily press. Winkler, Bochum 1990, ISBN 3-924517-30-4 .

- Meinolf Rohleder, Burkhard Treude: New Prussian (cross) newspaper. Berlin (1848-1939) . In: Heinz-Dietrich Fischer (Ed.): German newspapers from the 17th to the 20th century . Pullach near Munich 1972, pp. 209-224.

- Burkhard Treude: Conservative Press and National Socialism. Content analysis of the "Neue Preußische (Kreuz-) Zeitung" at the end of the Weimar Republic (= Bochum studies on journalism and communication studies; 4). Study extension Brockmeyer, Bochum 1975.

- Theodor Fontane in literary life. Newspapers and magazines, publishers and associations (= publications of the Theodor Fontane Society; 3). Shown v. Roland Berbig among employees v. Bettina Hartz. de Gruyter, Berlin a. a. 2000, ISBN 3-11-016293-8 , pp. 61-70.

- Dagmar Bussiek: “With God for King and Fatherland!” Die Neue Preußische Zeitung (Kreuzzeitung) 1848–1892 (= series of scholarship holders of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung; 15). Lit, Münster u. a. 2002, ISBN 3-8258-6174-0 .

Web links

- Front page from July 24, 1914 on the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum to Serbia

- Front page from January 9, 1919 on the reign of terror in Berlin .

- Digital copies of the years 1857, 1858, 1859, 1867 and 1868. Berlin State Library ; The digital library

Individual evidence

- ↑ Stefan Schilling: The Destroyed Legacy: Berlin Newspapers of the Weimar Republic in Portrait. Dissertation. Norderstedt 2011, p. 405.

- ↑ Austrian Academy of Sciences: http://www.oeaw.ac.at/cgi-bin/cmc/bz/vlg/0870/

- ^ Stephan Zick: Myth "Bismarck's Social Policy": Actors and Interests of Social Legislation in the German Empire. Dissertation. Norderstedt 2016, p. 47.

- ↑ Michael Dreyer: Kreuzzeitung (1848-1939). In: Handbook of Antisemitism . Walter de Gruyter, 2013, p. 418.

- ↑ a b c Dagmar Bussiek: With God for King and Fatherland! The Neue Preussische Zeitung (Kreuzzeitung) 1848–1892 . LIT Verlag, Münster 2002, p. 7 ff.

- ↑ Otto-Ernst Schüddekopf : The German domestic policy in the last century and the conservative thought. The connections between foreign policy, internal governance and party history, presented in the history of the Conservative Party from 1807 to 1918, volumes 1807–1918. Verlag Albert Limbach, 1951, p. 30.

- ^ Stephan Zick: Myth "Bismarck's Social Policy": Actors and Interests of Social Legislation in the German Empire. Dissertation. Norderstedt 2003, p. 47.

- ↑ Hans Dieter Bernd: The instrumentalization of anti-Semitism and the stab in the back legend in the Kreuz newspaper . In: The Elimination of the Weimar Republic on the “Legal” Way: The Function of Anti-Semitism in the Agitation of the Leading Class of the DNVP , chap. 6. Dissertation. Bochum 2004, p. 171 ff.

- ↑ Dagmar Bussiek: With God for King and Fatherland! The Neue Preussische Zeitung (Kreuzzeitung) 1848–1892 . LIT Verlag, Münster 2002, p. 18.

- ↑ a b Bernhard Studt: Bismarck as an employee of the “Kreuzzeitung” in the years 1848 and 1849. Dissertation. Kröger Druckerei, Blankenese 1903, p. 6.

- ↑ a b Dagmar Bussiek: With God for King and Fatherland! The Neue Preussische Zeitung (Kreuzzeitung) 1848–1892 . LIT Verlag, Münster 2002, p. 37.

- ↑ Dagmar Bussiek: With God for King and Fatherland! The Neue Preussische Zeitung (Kreuzzeitung) 1848–1892 . LIT Verlag, Münster 2002, p. 123.

- ^ Moritz Busch: Diaries. Second volume: Count Bismarck and his people during the war with France from diary sheets. Verlag Grunow, Leipzig 1899, p. 224.

- ↑ Reinhart Koselleck : Prussia between reform and revolution. Klett-Cotta, 1987. p. 111 ff.

- ↑ Ursula E. Koch: Berlin Press and European Events 1871. Colloquium Verlag, 1978, p. 76.

- ^ Heide Streiter-Buscher: Theodor Fontane. False correspondence. Walter de Gruyter, 1996, p. 36.

- ^ Edgar Bauer: Confident Reports on European Emigration in London 1852–1861. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 1989, p. 271.

- ^ Eckhard Heftrich: Theodor Fontane and Thomas Mann. Lectures at the International Colloquium in Lübeck 1997. Klostermann Vittorio GmbH, 1998, p. 60.

- ↑ Ursula E. Koch: Berlin Press and European Events 1871. Colloquium Verlag, 1978, p. 72.

- ↑ Karl Ernst Jarcke, George P. Phillips, Guido Görres, Josef Edmund Jörg, Georg Maria von Jochner: Historical-political papers for Catholic Germany. Volume 75. Literary-Artistic Institution, Munich 1875, p. 471.

- ^ Kurt Franke: Democracy Learning in Berlin: 1st Berlin Forum for Political Education 1989. Springer-Verlag, 2013, p. 71 (newspaper studies part 15).

- ^ Heide Streiter-Buscher: Theodor Fontane. False correspondence. Walter de Gruyter, 1996, p. 20.

- ^ Lothar Gall: Bismarck. The white revolutionary. Ullstein, 2002, p. 545 f.

- ↑ Ursula E. Koch: Berlin Press and European Events 1871. Colloquium Verlag, 1978, p. 80.

- ↑ Falko Krause: The light rail in Berlin: planning, construction, effects. Diplomica Verlag, 2014, p. 66.

- ↑ Otto plant: Bismarck - The founder of the empire. CH Beck, 2008, p. 396.

- ^ Paul Bang: Writings on Germany's Renewal, Volume 4. JF Lehmann, 1934, p. 404.

- ↑ Dagmar Bussiek: With God for King and Fatherland! The Neue Preussische Zeitung (Kreuzzeitung) 1848–1892 . LIT Verlag, Münster 2002, p. 235.

- ^ Fritz Stern : Gold und Eisen: Bismarck and his banker Bleichröder. Ullstein, 1978, p. 580 f.

- ↑ Dagmar Bussiek: With God for King and Fatherland! The Neue Preussische Zeitung (Kreuzzeitung) 1848–1892. LIT Verlag, Münster 2002, p. 242.

- ↑ Timo Stein: Between anti-Semitism and criticism of Israel: anti-Zionism in the German left. Springer-Verlag, 2011, p. 17 f.

- ^ Daniela Kasischke-Wurm: Anti-Semitism in the mirror of the Hamburg press during the German Empire, 1884-1914. LIT Verlag, 1997, pp. 97-98.

- ↑ Shulamit Volkov : Jewish assimilation and Jewish idiosyncrasy in the German Empire. In: Past and Present: Historical Journal for Social Science, Volume 9. Göttingen 1983, p. 132.

- ↑ Michael Fleischer: Come on, Cohn. Fontane and the Jewish question. Taschenbuch-Verlag, 1998, p. 46.

- ^ Hans-Joachim Schoeps: Jewish supporters of the Conservative Party of Prussia. In: Journal of Religious and Intellectual History. Vol. 24, No. 4 (1972), pp. 337-346.

- ^ Hans Manfred Bock: Conservative intellectual milieu in Germany: his press and his networks, 1890-1960. Lang-Verlag, 2003, p. 60 f.

- ↑ cf. German Monetary History Section Mark (1871–1923)

- ↑ Hammerstein, Wilh., Freiherr von . In: Brockhaus Konversations-Lexikon 1894–1896, supplement volume 1897, p. 528.

- ↑ Bernhard Studt: Bismarck as an employee of the "Kreuzzeitung" in the years 1848 and 1849. Dissertation. Kröger Druckerei, Blankenese 1903, p. 6.

- ^ Margot Lindemann, Kurt Koszyk: History of the German press. Volume 2. Colloquium Verlag, 1966, p. 138.

- ↑ Kurt Koszyk, Karl Hugo Pruys: Dictionary for journalism. Walter de Gruyter, 1970, p. 205.

- ↑ cf. German Monetary History Section Mark (1871–1923)

- ↑ cf. Information on the top left of every title page from June 1913

- ^ Klaus Meyer: Theodor Schiemann as a political publicist. Verlag Rütten & Loening, 1956, p. 9 f.

- ↑ John Hiden: Defender of minorities. Paul Schiemann 1876–1944. Verlag Hurst, 2004, p. 39.

- ^ Front page of the Kreuzzeitung dated August 7, 1914, see illustration above

- ^ Andreas Leipold: The assessment of Kaiser Wilhelm II. GRIN Verlag, 2008, p. 2.

- ↑ Friedhelm Boll u. a. (Editor): Archives for Social History. Volume 45. Verlag für Literatur und Zeitgeschehen, 2005, p. 561.

- ^ Heinz Reif: Lines of development and turning points in the 20th century. Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 2001, p. 103.

- ↑ Martin Kohlrausch: The monarch in the scandal: the logic of the mass media and the transformation of the Wilhelmine monarchy. Akademie Verlag, 2005, p. 111 f.

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz, Michael Dreyer: Handbook of Antisemitism. Walter de Gruyter, 2013, p. 419.

- ↑ Werner Bergengruen: The existence of a writer in the dictatorship. Oldenbourg Verlag, 2005, p. 236.

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz, Michael Dreyer: Handbook of Antisemitism. Walter de Gruyter, 2013, p. 419.

- ↑ Mirjam Kübler: Judas Iskariot - The occidental image of Judas and its anti-Semitic instrumentalization under National Socialism. Waltrop-Verlag, 2007, p. 104 f.

- ↑ 1918–1933: The Development of Christian Parties in the Weimar Republic . Konrad Adenauer Foundation

- ^ The German Center Party (center) . German Historical Museum

- ^ Heinrich Küppers: Joseph Wirth. Parliamentarians, ministers and chancellors of the Weimar Republic. Steiner-Verlag, 1997, p. 10 f.

- ↑ Federal Archives; Detail in: R 43 I / 1226, p. 38.

- ↑ Federal Archives; Execution of the judgment in: R 43 I / 1226, Bl. 179–186.

- ^ Andreas Kraus: History of Bavaria: from the beginnings to the present. CH Beck, 2004, p. 270.

- ↑ Karsten Schilling: The Destroyed Legacy: Portrait of Berlin Newspapers of the Weimar Republic. Dissertation. Norderstedt 2011, p. 411.

- ^ Heinz Dietrich Fischer: German newspapers from the 17th to the 20th century. Verlag Documentation, 1972, p. 224.

- ↑ "Degeneracy of the Election Campaign". In: Neue Kreuzzeitung, October 8, 1932 (issue B).

- ↑ Dirk Blasius: Weimar's end. Civil War and Politics 1930-1933 . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2005, p. 107.

- ^ Heinrich Brüning: Memoirs 1918–1934. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1970, p. 467.

- ↑ Karsten Schilling: The Destroyed Legacy: Portrait of Berlin Newspapers of the Weimar Republic. Dissertation. Norderstedt 2011, p. 411.

- ^ Title of the morning edition of the Kreuzzeitung January 1, 1929 and Georg Foertsch: Last Appeal . In: Kreuzzeitung, March 12, 1932.

- ^ Heinz Dietrich Fischer: German newspapers from the 17th to the 20th century. Verlag Documentation, 1972, p. 224.

- ↑ Dankwart Guratzsch: Power through organization. The foundation of the Hugenberg press empire. Bertelsmann, 1974, p. 27 ff.

- ↑ Kurt Koszyk, Karl Hugo Pruys: Dictionary for journalism. Walter de Gruyter, 1970, p. 205.

- ↑ Larry Eugene Jones, Wolfram Pyta: I am the last Prussian: the political life of the conservative politician Kuno Graf von Westarp. Böhlau Verlag, 2006, p. 182.

- ^ Emil Ludwig: Hindenburg. Legend and Reality. Rütten & Loening, 1962, p. 213.

- ↑ Hans Frentz: The Unknown Ludendorff: The general in his environment and epoch. Limes Verlag, 1972, p. 270.

- ^ Carl von Ossietzky: The New World Stage: weekly for politics, art, economy. Volume 30. Issues 27–52. Weltbühne, 1932, p. 1027.

- ↑ Jesko von Hoegen: The hero of Tannenberg: Genesis and function of the Hinderburg myth. Böhlau Verlag, 2007, p. 363.

- ↑ Burkhard Treude: Conservative Press and National Socialism: Content analysis of the Neue Preußische (Kreuz-) Zeitung at the end of the Weimar Republic. Study publisher Dr. N. Brockmeyer, 1975, p. 17.

- ^ Otto Altendorfer, Ludwig Hilmer: Medienmanagement, Volume 2: Medienpraxis. Media history. Media regulations. Springer-Verlag, 2015, p. 164.

- ^ Carl von Ossietzky: The New World Stage: weekly for politics, art, economy. Volume 30, Issues 27-52. Verlag der Weltbühne, 1934, p. 1435.

- ↑ Larry Eugene Jones, Wolfram Pyta: I am the last Prussian: the political life of the conservative politician Kuno Graf von Westarp. Böhlau Verlag, 2006, p. 29 f.

- ↑ Tobias Jaecker: Journalism in the Third Reich. Free University of Berlin, Friedrich Meinecke Institute for History, 2000, p. 3 f.

- ^ Burkhard Treude: Conservative Press and National Socialism. Study publisher Dr. N. Brockmeyer, 1975, p. 30.

- ^ Kurt Koszyk: Deutsche Presse 1914-1945. History of the German Press, Part III. Colloquium Verlag, 1972, p. 72 f.

- ^ Norbert Frei, Johannes Schmitz: Journalism in the Third Reich. CH Beck, 2011, p. 47.