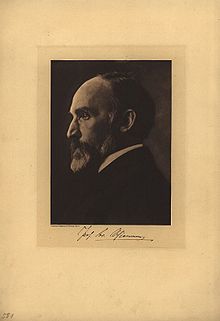

Theodor Schiemann

Theodor Schiemann (* July 5 jul. / 17th July 1847 greg. In Grobin , Kurland , † 26 January 1921 in Berlin ) was a German historian , archivist , Professor of East European History in Berlin, political writer and founder of the East European Studies in Germany.

Life

Theodor Schiemann was a member of the German Baltic Schiemann family, which was shaped by conservative national thinking and Christian-Protestant faith . He attended grammar school in Mitau and studied history at the University of Dorpat from 1867 to 1872 . Here Carl Schirren and his fight against the Russification of the Baltic States became a role model. It then worked as a private tutor in Mitau and as an archivist in Gdansk . In 1874 he received his doctorate from the University of Göttingen . Later he wrote about this time in his memoirs: What I took with me into bourgeois life was a firm German national consciousness and the decision to devote my life to the German cause in the Baltic provinces .

Schiemann married Caroline von Mulert and had five children, including the future botanist Elisabeth Schiemann . In order to take care of the family he found employment as a high school teacher in Fellin and from 1883 as a city archivist in Reval .

Because of the Russification policy under Tsar Alexander III. Like many other Baltic Germans, Schiemann moved with his family to Berlin in 1887, where Heinrich von Treitschke became his mentor. In 1889 he found a job in the Secret State Archives. Schiemann taught at the War Academy . He became a member of the RSC-Corps Holsatia Berlin. He was able to do his habilitation quickly and became a private lecturer for middle and modern history at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität . In 1892 he received the newly established extraordinary professorship for Eastern European history and regional studies at the university. On June 30, 1902, Schiemann succeeded in founding the seminar for Eastern European history and regional studies , the cornerstone for the institutionalization of German Eastern European research. He was appointed full professor at the beginning of 1906 and was one of the editors of the journal for Eastern European history .

Journalistic and political work

The four-volume history of Russia under Nicholas I , his life's work, is a strongly personal presentation in which the history of diplomacy is always in the foreground.

From 1887 to 1893 Schiemann wrote as a Berlin correspondent for the Münchener Allgemeine Zeitung and from 1892 to 1914 for the Neue Preußische Zeitung, the " Kreuzzeitung ". In doing so, he represented a policy of strength and a conception of foreign policy that focused on the "coexistence" of Germany and Great Britain and the "coexistence" of Germany and Russia .

At that time, the field of Eastern European history was closely linked to politics. Through his books and the political articles in the Kreuzzeitung, Schiemann attracted the attention of Kaiser Wilhelm II and a friendly relationship developed through which Schiemann was able to exert political influence as an advisor, especially on issues relating to the Baltic States .

During the First World War , Schiemann propagated the “Russian danger” in a large number of writings and advocated an annexationist policy with regard to the Baltic States. He became the eloquent advocate of the idea that we should create a German community out of the Baltic Sea . Several German-Baltic associations served him as a medium. In his memorandum The German Baltic Provinces of Russia in April 1915, he advocated the thesis that Estonia , Livonia and Courland formed a geographical and cultural unit and were of interest to the Reich not only because of their German character, but also because of their commercial importance.

The entire official German “border state policy” was mainly influenced by the “Schiemann School” and its teaching by the Russian nationality state . Schiemann's “Eastern European School”, which was led by Paul Rohrbach , had a decisive influence on this “border state policy”, ie the dissolution of multinational Russia. Baltic German journalists such as Schiemann and Rohrbach had a lasting influence on the predominantly anti-Russian and Ukrainophile public opinion in Germany and thereby favored the German government's policy of “revolutionizing” or “liberating” Ukraine .

Despite their tendencies towards Germanization , such as the planned settlement of Russian Germans in the Baltic States, the "Schiemann School" was a bitter opponent of the Pan-Germans and was one of their sharpest propagandistic opponents. In contrast to the Pan-German “master folk attitudes”, it wanted to grant autonomy to the Eastern European “marginalized peoples”. There were also sharp disputes with political liberalism , especially personal ones between Theodor and his nephew, the politician Paul Schiemann . The Russian February Revolution of 1917 gave the Schiemann School and the Ukrainian publicists a considerable boost because their plans became more real and they tried to gain more influence over the civil and military leadership of the Reich.

When Schiemann was appointed curator of the university of the conquered city of Dorpat by the emperor in 1918 , he spoke in his opening speech about the liberation of old Livonia from the coercion of Russian tyranny and the pressure of Russian megalomania .

Theodor Schiemann was known as Germany's expert on Russia. He considered the Russian Empire to be “morbid”, only held together by the “brackets of autocracy”. His image of the Russian people was shaped by prejudice, as he attested to political immaturity because of his alleged oriental orientation, which he described as the result of many years of autocratic rule. It was Schiemann's merit to have laid the foundations for scientific research into Russia in Germany.

His grave in the old garrison cemetery in Berlin-Mitte no longer exists.

Memberships

- Society for History and Archeology of the Baltic Provinces of Russia , corresponding member

Fonts (selection)

- The oldest Swedish cadastre of Livonia and Estonia: a supplement to the Baltic goods documents (on behalf of the Fellin Literary Society ). Reval: F. Kluge, 1882 ( digitized from the University of Tartu ).

- Russia, Poland and Livonia until the 17th century. 2 volumes. 1886/1887 (= general history in individual representations ).

- Library of Russian Memories. 7 volumes. 1893-1895.

- History of Russia. 4 volumes. 1904-1919.

literature

- Klaus Meyer: Russia, Theodor Schiemann and Victor Hehn. In: Norbert Angermann , Michael Garleff , Wilhelm Lenz (eds.): Baltic provinces, Baltic states and the national. Festschrift for Gert von Pistohlkors on his 70th birthday. Lit, Münster 2005, ISBN 3-8258-9086-4 , pp. 251–288 (= writings of the Baltic Historical Commission , 14).

- Wilhelm Lenz: Theodor Schiemann's Revaler Years (1883–1887). In: Norbert Angermann, Michael Garleff, Wilhelm Lenz (eds.): Baltic provinces, Baltic states and the national. Festschrift for Gert von Pistohlkors on his 70th birthday. Lit, Münster 2005, ISBN 3-8258-9086-4 , pp. 227-250 (= writings of the Baltic Historical Commission , 14).

- Carola L. Gottzmann / Petra Hörner: Lexicon of the German-language literature of the Baltic States and St. Petersburg . 3 volumes, Verlag Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-11019338-1 , Volume 3, pp. 1132–1136.

- Kurt Zeisler: Theodor Schiemann as the founder of German imperialist research on the East. Dissertation, Halle 1963.

- Roderich von Engelhardt: The German University of Dorpat in its intellectual historical significance . Franz Kluge Reval 1933 (reprint 1969), p. 348 f.

Web links

- Literature by and about Theodor Schiemann in the catalog of the German National Library

- Schiemann, Theodor . In: East German Biography (Kulturportal West-Ost)

- Baltic Historical Commission (ed.): Entry to Schiemann, Theodor. In: BBLD - Baltic Biographical Lexicon digital

Individual evidence

- ↑ Helmut Altrichter: Schiemann, Theodor. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 22, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-428-11203-2 , pp. 741 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ↑ a b c d e Schiemann, Theodor . In: Ostdeutsche Biographie (Kulturportal West-Ost).

- ↑ a b c d Rudolf Vierhaus (Ed.): German Biographical Encyclopedia . Volume 8, Saur, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-598-25030-9 , p. 849.

- ↑ Quoted from Klaus Meyer: Eastern European History. In: Reimer Hansen (ed.): History in Berlin in the 19th and 20th centuries. Personalities and institutions . Verlag de Gruyter, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-11-012841-1 , pp. 553-570, here p. 556.

- ^ Klaus Meyer: Theodor Schiemann as a political publicist. Verlag Rütten & Loening, Frankfurt am Main / Hamburg 1956, p. 19. (= North and East European history studies. Volume 1).

- ↑ John Hiden : Defender of minorities. Paul Schiemann 1876–1944. Hurst Publisher, London 2004, ISBN 1-85065-751-3 , p. 5.

- ↑ CORPS - the magazine. (Deutsche Corpszeitung), 110 year, issue 1/2008, p. 25.

- ^ Klaus Meyer: Eastern European History. In: Reimer Hansen (ed.): History in Berlin in the 19th and 20th centuries. Personalities and institutions . Verlag de Gruyter, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-11-012841-1 , pp. 553-570, here pp. 558 f.

- ↑ Dittmar Dahlmann (Ed.): Hundred Years of Eastern European History. Past, present and future. Verlag Steiner, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-515-08528-9 , p. 7; and 11.

- ^ Klaus Meyer: Theodor Schiemann as a political publicist. Verlag Rütten & Loening, Frankfurt am Main / Hamburg 1956, p. 86. (= North and East European History Studies , Volume 1).

- ^ Klaus Meyer: Eastern European History. In: Reimer Hansen (ed.): History in Berlin in the 19th and 20th centuries. Personalities and institutions . Verlag de Gruyter, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-11-012841-1 , pp. 553-570, here p. 555.

- ^ Klaus Meyer: Theodor Schiemann as a political publicist. Verlag Rütten & Loening, Frankfurt am Main / Hamburg 1956, p. 9 f. (= Northern and Eastern European History Studies , Volume 1).

- ↑ John Hiden: Defender of minorities. Paul Schiemann 1876–1944. Hurst Verlag, London 2004, ISBN 1-85065-751-3 , p. 39.

- ↑ Ulrike von Hirschhausen : The limits of commonality. Germans, Latvians, Russians and Jews in Riga 1860–1914. Verlag Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2006, ISBN 3-525-35153-4 , p. 364.

- ↑ Oleh S. Fedyshyn: Germany's Drive to the East and the Ukrainian Revolution 1917-1918 . New Brunswick / New Jersey 1971, p. 21 ff.

- ^ Peter Borowsky : German Ukraine Policy 1918 with special consideration of economic questions. Lübeck / Hamburg 1970, p. 16 and 292.

- ↑ Oleh S. Fedyshyn: Germany's Drive to the East and the Ukrainian Revolution 1917-1918 . New Brunswick / New Jersey 1971, p. 25 f.

- ↑ Ulrike von Hirschhausen: The limits of commonality. Germans, Latvians, Russians and Jews in Riga 1860–1914. Verlag Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2006, ISBN 3-525-35153-4 , p. 115.

- ↑ John Hiden: Defender of minorities. Paul Schiemann 1876–1944. Verlag Hurst, London 2004, ISBN 1-85065-751-3 , p. 31 ff.

- ↑ Oleh S. Fedyshyn: Germany's Drive to the East and the Ukrainian Revolution 1917-1918 . New Brunswick / New Jersey 1971, p. 42.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Schiemann, Theodor |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German historian |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 17, 1847 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Coarse |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 26, 1921 |

| Place of death | Berlin |