Literature of the Restoration Era

The literature of the restoration epoch includes the literature of the period from 1815–1848 , which is essentially characterized by the contemplative Biedermeier and the also politically understood Vormärz from the end of the Vienna Congress in 1815 to the beginning of the bourgeois-liberal March Revolution in 1848.

For epochs

With regard to the literature of the period from 1815 to 1848, one can distinguish between different currents. The politically committed literature of the Vormärz and the seemingly idyllic Biedermeier can be highlighted most clearly . With his three-volume work, the Biedermeier Period , Friedrich Sengle emphasized the similarities between these literary directions. According to his observation, all authors reacted to the challenge of modernization, either by opening up to the new era and becoming socially and politically active, or by fearfully rejecting modern developments and emphasizing traditional values.

The name of the era is still fluctuating. Sengles “Biedermeier Era” did not catch on because the term is one-sided, the alternative “restoration era” is ambiguous because there have been political restorations in other times as well.

Spiritual currents of the time

The literature of this era is very diverse and shaped by Christian awakening literature and the idyllic Biedermeier on the one hand, the committed literature of Vormärz and Young Germany and the agitation poems, for example by Georg Herwegh, on the other. Nevertheless, it is possible to view the literature of this period as a unit.

All authors were aware that they were living in a transition period. They had witnessed the great French Revolution and learned in 1815 that the old conditions were largely restored with the Congress of Vienna . As a result of the Karlsbad resolutions in 1819, fraternities were banned and freedom of teaching and the press was severely restricted. So-called “Biedermeier quietism ” also spread among intellectuals , accompanied by a retreat into the private sphere of the family. One practiced “gentle modesty” ( Eduard Mörike ) and cultivated the “devotion of the little one” ( Adalbert Stifter ).

However, it was clear to many contemporaries that this would not stay that way and that progress could not be stopped. Church and religion had apparently survived the revolution unscathed, but atheism became a way for enlightened intellectuals to escape the coercion of these institutions. The economy was still oriented towards the ideal of the craftsman, but the guilds had been abolished in Prussia , freedom of trade was introduced and industrialization broke through. The old political powers were restored, but the territorial shifts of the Napoleonic era persisted and the liberal movement fought for political participation by the bourgeoisie, which eventually led to the March Revolution of 1848.

The poets felt this time and the people in it as torn, and torn, between contradictions, who are unable to make consistent decisions, are typical of the literature of the epoch. Immermann describes this attitude towards life in his autobiographical book Die Jugend 25 years ago as divided and double, pathological, nervous and weak. This attitude is also reflected in the characters in the novel, such as Mörike's painter Nolten and especially in the friend of the title character, Larken .

The confrontation with Goethe was also formative for the poets of the era . They were aware that after the height of German classical music their works could only be epigonal . August Graf von Platen-Hallermünde and Friedrich Rückert tried to use ancient and oriental models to open up new forms of poetry, but their works seem primarily artificial and Rückert in particular was often parodied. Mörike, on the other hand, succeeded in productively developing ancient forms in his poems based on Goethe's example.

Schiller's classic role model also played a role in drama, for example with Franz Grillparzer .

On the other hand, there was a conscious turning away from classical literature. With the poets of Vormärz, poetry of experience was basically only parodic. Christian Dietrich Grabbe wrote a drama of the open form with Napoleon or Die Hundred Tage and Georg Büchner wrote a documentary drama with Danton's death .

In prose, which was not tied to ancient traditions, the forms literally exploded: travelogues, reports, essays and character sketches developed into popular genres.

The poets of this epoch were not just concerned with dealing with the literary forms of the Classical period. They also accused Goethe of his “Olympic” coldness and opposed him with their commitment. Heinrich Heine summed up the feeling of many when he wrote that the death of Goethe meant the end of the art era . This saying contains both: the distance to a time when art was only practiced for art's sake and the social realities ignored, but at the same time also the sadness about the loss of the possibility of an autonomous art .

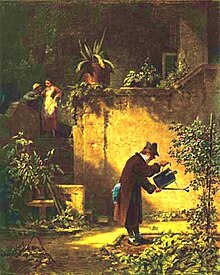

Biedermeier

The Biedermeier man was caricatured as a petty bourgeois who had been depoliticized and driven by naive, authority-loyal aspirations and addiction to harmony . These and similar connotations cling to the by no means insignificant literature of Biedermeier to this day, such as B. Franz Grillparzer's The Dream of a Life that today can hardly be read without irony:

- Only one thing is happiness down here

- One: the inner quiet peace

Characteristic of the Biedermeier is the emphasis on calm, order, civil tranquility, modesty, moderation and the quiet, inconspicuous; the demonic is avoided. As a result, smaller forms are preferred, such as mood pictures, sketches or novels. It is certainly true to say that a number of Biedermeier authors were determined by a conservative to reactionary attitude and longed for a simple, harmonious life in a world increasingly shaped by industrialization and the associated urbanization . The work of Heinrich Clauren is characteristic of this tendency , especially his story Mimili , with which Biedermeier literature began successfully in 1816. In this sense, the literature of the Biedermeier period is, as can already be seen in some respects from Romanticism , idyllic and turned away from current events and thus a reflex on the social present, on an alienation and emptying of meaning, which is reflected in the return to the elementary Experience and creation should be escaped. In contrast to Romanticism, whose writers were still mainly recruited from the nobility , the Biedermeier writers were citizens who often came from rather simple backgrounds.

For the poets of the Biedermeier era, nature was no longer a projection surface of longing pain in the world and the ego, but goods and creation and to be closely observed. This happened not only from a Christian, but also from a pantheistic point of view. Emerging research trips served to appreciate all the individual elements of this nature, many of which were also gladly collected, cataloged and then exhibited at home. And even if it was precisely this esteem that pointed to the Christian God as the Creator, religiosity did not close in , but actually promoted tentative empirical interests. The criticism of the perceived alienation, however, also created an elitism that distinguished itself from lightness and licentiousness.

Stifter formulates this as a “gentle law”: “[...] Just as it is in external nature, so it is also in internal nature, in that of the human race. A whole life full of justice, simplicity, self-conquest, intellect, effectiveness in one's circle, admiration for the beautiful combined with a serene and serene death, I consider great: powerful movements of the mind, terribly rolling anger, the desire for vengeance, the inflamed spirit who strives for activity, outlines, changes, destroys and in the excitement often throws his own life down, I do not consider them bigger, but rather smaller, since these things are so well only the productions of single and one-sided forces, like storms, fire-breathing mountains , Earthquake. Let us seek to see the gentle law by which the human race is guided. [...] It is [...] the law of justice, the law of custom, the law that wants everyone to be respected, honored and safe next to the other, so that he can pursue his higher human career, himself Acquire the love and admiration of his fellow human beings that he is guarded as a treasure, just as every person is a treasure for all other people. This law is everywhere where people live next to people. "(Preface to Bunte Steine , 1853)

The conclusion of the time can generally be seen in Stifter's work. His first novel Nachsommer (which he himself called “Narrative”) did not appear until 1857, but was nevertheless considered the most excellent work of the Biedermeier period. Stifter's Bildungsroman Postsommer is actually not part of the Biedermeier period. Rather, this Bildungsroman belongs to the canon of realism literature and is an example of this peculiar genre in Germany. Stifter worked on Rosegger and Ganghofer , on Heyse , Freytag and Wildenbruch as well as directly in the following bourgeois realism , on Storm and Fontane and through them on Thomas Mann and Hesse .

Stifter's work, which repeatedly caused controversy, also shows elements that go beyond the Biedermeier. In the novella Brigitta, for example, in addition to the fatalistic sophistication, there is also emancipatory aspects of women's rights.

Other Biedermeier writers, more or less, are Annette von Droste-Hülshoff , Franz Grillparzer , Wilhelm Hauff , Karl Leberecht Immermann , Nikolaus Lenau , Eduard Mörike , Wilhelm Müller (the "Greek miller"), Johann Nepomuk Nestroy , Ferdinand Raimund , Friedrich Rückert , Friedrich Hebbel and Leopold Schefer . Pure Biedermeier literature is found much more in the trivial area, in literary calendars and the like. Ä.

Literary pre-March in Germany

The term “Vormärz” is a vague collective term for the oppositional to revolutionary political literature of the decades before the German March Revolution of 1848. The beginning of this literary era is controversial; some put it in 1815 ( Congress of Vienna ), others in 1819 ( Karlsbader Resolutions ), 1830 ( July Revolution ) or 1840. The literary works of Georg Büchner ( Woyzeck , Lenz , Der Hessische Landbote , Leonce and Lena ) are also included in the literature of the Vormärz , Danton's death ) and the young Germany's group of authors . The Vormärz, which aimed for political changes in Germany and hoped for an improvement in living conditions, stood in contrast to the literature of the conservative, restorative and politically resigned Biedermeier. Important genres of the pre-March period are the letter and the travelogue .

The boy Germany , whose publications in 1835 by the German Bundestag were banned, is probably the most important group of authors that time. The representatives of this current wanted to achieve the political consciousness of the bourgeoisie and demanded a politically committed literature with the aim of revolution. The main representatives were Christian Dietrich Grabbe , Ludwig Börne (letters from Paris), Heinrich Laube , August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben , Ferdinand Freiligrath (Ca ira; new political and social poems), Bettina von Arnim (this book belongs to the king), Georg Weerth (Humorous sketches from German commercial life, life and deeds of the famous knight Schnapphanski), Louise Aston (My Emancipation) and Georg Herwegh (poems of a living person).

Heinrich Heine , who is sometimes also attributed to Young Germany, distanced himself from these “ tendency poets ” for aesthetic reasons , because in their “rhyming newspaper articles” they advocated changes in a too rebellious manner and neglected poetry , art and aesthetics . Nevertheless, as the poet of Vormärz, Heine shared the social criticism of the Young Germans and his works were banned along with those of Young Germany in 1835.

See also

literature

- Sengle, Friedrich: Biedermeier period. German literature in the area of tension between restoration and revolution 1815-1848. 3 vols. Metzler, Stuttgart 1971–1980.

- Horst Albert Glaser (Ed.): German literature. A social story. Vol. 6: Bernd Witte (Ed.): Biedermeier, Young Germany, Democrats 1815-1848. Reinbek: Rowohlt 1980 (rororo 6255).

- Günter Blamberger , Manfred Engel , Monika Ritzer (eds.): Studies on the literature of early realism. Frankfurt: Lang 1991.

- Hanser's social history of German literature . Lim. v. Rolf Grimminger. Vol. 5: Gerd Sautermeister, Ulrich Schmidt (ed.): Between Revolution and Restoration 1815-1848 . Hanser, Munich 1998 (dtv 4347).

- Joachim Bark: Biedermeier and Vormärz / Bourgeois Realism. Klett, Stuttgart 2001 (History of German Literature, Vol. 3) ISBN 3-12-347441-0 .

- Manfred Engel : Pre-March, early realism, Biedermeier period, restoration period? Comparative attempts at contouring for a contourless epoch. In: Oxford German Studies 40 (2011), 210–220.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Kurt Rothmann: Small history of German literature. Reclams Universal Library, 20th edition Stuttgart 2014, chap. 13.