The late summer

The post-summer with the subtitle Eine Erzählung ( 1857 ) is a novel in three volumes by Adalbert Stifter . The work is one of the great literary novels of the 19th century. What is described is an idealized, partially synthetic path of a young person, shielded from life, into adulthood.

content

In the late summer, Stifter tells an educational, love and family story. In it, the life courses of two mirror-inverted couples are so intertwined that the younger couple finds fulfillment where the older only experiences a late summer. The negative experiences of the older couple create insight, orientation and material conditions as a prerequisite for the successful life of the younger ones.

Chapter overview

First volume

- The domesticity

- The hiker

- The contemplation

- The accommodation

- The good bye

- The visit

- The encounter

Second volume

- The extension

- The approach

- The view

- The party

- The Bund

Third volume

- The unfolding

- The trust

- The message

- The review

- The conclusion

Contents of the first chapter

In the first chapter of the first volume, Die Häuslichkeit, the first-person narrator Heinrich Drendorf, the name is only mentioned III.5, describes his growing up in the unnamed "city", according to the interpreters of Vienna . His family initially rented the first floor of a town house: “ We each had a room in the apartment ” (9) , and later our own house with a garden in the suburbs. The busy father, who comes from a simple rural background, has worked his way up from clerk to owner of a successful commercial business and can only seldom “ spare a moment ” (10) for idle contemplation, enables his son and daughter Klotilde to fail himself An upbringing based on the idea of man of idealistic philosophy , with a calm severity that even the mother, " a friendly woman " (11) , does not dare to break out of " fear of the father ". Already at the beginning there appears in the person of the father, who in the course of his life has built a library and a small art collection and in whom “ no room is allowed to show the traces of immediate use ” (10) , an idea of order that follows According to the ancient motto unum est verum pulchrum et bonum, beauty and morality are closely linked - although this is repeatedly broken up, be it intentional or unintentional, by the echoes of commercial pragmatism:

- “ As we gradually grew up, we were drawn more and more into the company of our parents. Father showed us his pictures and explained some of them to us. He said that he only had old ones who had a certain value, which one could always have if one should ever be obliged to sell the pictures. “ (15) .

It can also be seen here that reflecting on the old is conducive to education, as in the following the contemplation of art is like a contemplation of nature when the father explains that a successful work requires movement, but then “ movement is still again "And" rest in motion [...] the condition of every work of art " (ibid.) , Which already suggests the foundation of artistic aesthetics in the reception of creation .

With Heinrich's moral maturation, the strictness of his father's upbringing diminishes, gives way to a demand for responsibility in the gradual transfer of the management of the pension (which comes from the inheritance of Heinrich's great-uncle) to the boy and even enables openness, his goal and his To allow meaning to be found only where social convention demanded the opposite:

- " [...] what people resented my father [was] that he should have ordered me to have a class useful to civil society, so that I could devote my time and my life to it, and one day part consciously, mine To have done an obligation. "

- “ Against this draft, my father said that humans were not there first for the sake of human society, but for their own sake. And if everyone is there in the best way for his own sake, he is also there for human society. Whoever God had made the best painter in this world would be doing mankind a disservice if he wanted to become a judge, for example. “Since God“ already [directs] it that the gifts are properly distributed so that every work that is to be done on earth is done ”, everyone should follow“ his inner urge ”,“ which leads one to something. “ (17) . Heinrich's mentor Risach later expresses himself similarly: “The greater the power [of the disposition], the more I believe it works according to the laws peculiar to it, and the greatness inherent in man unconsciously strives towards his goal from the outside, and achieves the more effective, the deeper and more unwavering it strives. " (III, 2)

The openness that is given here to the development of the son is determined equally by echoes of a thought of entelechy such as predestination , as well as those of usefulness and order. It is precisely those who claim that “ they have become merchants, doctors, civil servants for the benefit of mankind ” (18), however, because “ in most cases it is not true ”, because they often only had “money and Good ”in the sense of the common good that is sworn. The good, however, is free not only from these, but from any purposes:

- “ God has not given us the benefit as an end in our actions, neither the benefit for us nor for others, but he has given the practice of virtue its own charm and beauty, which things the noble minds strive for. Anyone who does good because the opposite is harmful to the human race is already quite low on the ladder of moral beings. “ (19) .

The program of the novel is already given in the first chapter. The natural order, which is not created out of the compulsion of society, but out of the righteous person, creates morality and beauty in one - however not as the ultimate perfect result, but in the movement of lifelong maturation, which is accompanied by the equally necessary rest internalization.

Contents of the other chapters

Heinrich expands his theoretical knowledge to include areas of experience of working people and nature: He studies the agricultural, craft and industrial techniques and production methods from materials to products and, on hikes in the city's surroundings and then in the high mountains, researches plants, animals and rocks, draws them and compares the various forms with the scientific classifications. When looking from the high mountains, he notices the structural similarities with microscopic structures, such as the ice crystals on a window pane, and he has "endeavor [...] to trace the formation of this earth's surface and, by collecting many small facts in various places to expand the great and sublime whole ”(I, 2). When he is looking for protection from a thunderstorm, the fully blooming roses on a house wall lure him into the Asperhof or Rosenhof, where the older owner, the host, welcomes him in a friendly manner. His name, Gustav Freiherr von Risach, he hears I, 5 from village people and only III, 3 personally from him. Regular visits to the Rosenhaus deepen the relationship and the host becomes Heinrich's mentor and role model.

The educated and multi-faceted landlord, collector, natural scientist bought the old Aspermeierhof years ago and expanded it into a well-organized, effective agricultural operation from an ecological point of view and created a "blessed land made happy by God". Using the weather forecast as an example, he shows the visitor that people can gain insights beyond the technical measuring instruments through precise observations of the nature of insects, birds, plants, etc., since "every knowledge has outlets that one often does not suspect" and that "one does shouldn't neglect the smallest things if you don't yet know how they are related to the bigger ones ”. He uses this natural system and tries to optimize it, e.g. B. by soil refinement, planting suitable plants that serve as food for insects and birds. The prerequisite for success is conscientious work and careful handling: "Nobody can fully assess the value of these plants by caring for them". Next to the farm, Risach has built the “carpenter's house”: a restoration workshop for old furniture and equipment with a collection of construction plans and ornamental drawings by Master Eustach. His brother Roland roams the rural areas and buys old handicrafts that are worth restoring on behalf of Risach in order to preserve these values from decay. Because “in the old devices [...] there is a charm of the past and withered away, which becomes stronger and stronger in people when they get into the higher years. That is why he seeks to preserve what belongs to the past, just as he also has a past [...] Old habits have something calming about them, even if it is only of the existing and always happened ”(I, 4).

The host has set up a girl's sculpture in a temple-like design on the central marble staircase of his house, which he found in junk on a trip to Italy and which he soon acquired and which, at home, cleaned and polished, turns out to be a marble antique work of art. Almost exactly in the middle of the story, Heinrich reports - again a thunderstorm is involved - of an awakening experience in front of this girl's picture, which gives him access to art and which at the same time reflects his awakening love for Natalie, the daughter of Risach's friend Mathilde . Heinrich's fantasies merge the statue and Natalie and also a third figure, Nausikae, who comes to life for him when he reads the Odyssey: “The forehead, the nose, the mouth, the eyes, the cheeks [...] had the free, the high, the Simple, delicate and yet strong, which points to the fully formed body, but also to a peculiar will and a peculiar soul [...] Natalie thus came from the sex that had passed away and that was different and more independent than that present ”(I, 7).

Natalie and Mathilde come regularly to the rose bloom from their nearby castle, the Sternenhof, to the rose house, where Heinrich stops over and over again. In front of the fully bloomed roses on the wall of the manor house - meditative contemplation in front of the flowers - a ceremonial set-up takes place in which Heinrich is also classified without knowing their meaning. Only in III, 4, in retrospect , does Risach tell him about his unhappy childhood love, which only came true in old age. Gradually, under the knowing, but not interfering, company of Risach and Mathilde, under the spell of roses, the love between Heinrich and Natalie deepens and consolidates, both of whom have long been closed.

The mutual admission of love breaks out when the two of them meet one day - Heinrich is a guest at the Sternenhof - in a grotto that Mathilde has created on her country estate. The well nymph erected there is involved in the diverse relationship game that drives the story with the female figures in relation to the characters involved. In front of the picture, Heinrich and Natalie reveal in a conversation about the marble stone, the precious stones and above all about the elementary meaning of "water [...] as the moving life of the earth as the air is its tremendous breath" (II, 5) their soul community and swear eternal love. However, they make a marriage dependent on the consent of the parents, which, however, is not questionable for the reader from their knowledge of the parents. The love story of Heinrich and Natalie ends with the marriage.

Before Heinrich is ready for this bond, the host introduces him more and more to his cultural work over seven years of traveling between town and country. It extends equally to the surrounding nature and landscape, in which he, as the landlord, practices organic farming, as well as to the aesthetic design of the living space with the house as the focus. The artistic activity, which essentially collects and restores, follows a comprehensive beautification program, which focuses on the renovation of churches and altars in the area as well as on the manufacture of everyday utensils for the Asperhof and the Sternenhof. In addition to participating in Risach's activities, Heinrich immersed himself in works of art and studied the great authors from the natural sciences, history and literature, for whose understanding Risach provided him with detailed comments.

On his excursions, which are expanding more and more into higher mountain regions, Heinrich tries by drawing, collecting, measuring, building hypotheses to penetrate more and more precisely into the formations of the earth accessible to him and to create a documented image of the landscape with its lakes and mountain ranges. His explorations culminate in climbing a glacier in winter. He observes a sunrise, the magnificent description of which testifies to the transition from a scientific approach to nature to a transcendental one.

After Heinrich, as he says, has taken on the consecration of this undertaking, he can be initiated into the symbolism of the Rosenwand. In the "Communication" and the "Review", the penultimate chapters, Risach tells his adept the tragic prehistory of the post-summer world like an initiation that allows Heinrich to understand and relive the foundation events of the rose ceremony, and in it for him to be accepted into the adopted Risach family prepared.

Risach tells how he, an orphan from a modest background, came to the Heinbach estate as a young private tutor, where he was supposed to educate and teach Alfred, the son of the wealthy Makloden family. A passionate affection develops between Mathilde, Alfred's older sister, and Risach, unnoticed by Mathilde's parents. As if inspired by a foreign power, one day they confess their love and swear to one another to belong to one another forever. For a long time they keep their chaste love a secret. When Risach finally reveals himself to Mathilde's mother, something begins that Risach compares to the calamities in ancient tragedy. The girl's parents reproach him for abuse of trust. Because of the age of the daughter and Gustav's missing profession, they rejected the love bond at this point and suspended them on probation, and they demanded an immediate separation. Risach submits to the parents 'decision and lets the mother persuade her to tell Mathilde of the parents' command. The girl is stunned, indignant, deeply affected. She would have expected Gustav's opposition to the parents' prohibition, felt his behavior as an outrageous betrayal of love and declared the bond ended. She later marries Count Tarona and has two children with him, Natalie and Gustav.

The dramatic scene of the Bruch takes place in front of a rose hedge in Heinbach's garden. Mathilde, in a passionate outburst, calls upon the thousand blooming roses as witnesses to a love that she considered indestructible. In immense, silent pain Risach reaches into the rose branches, presses the thorns into his hand and lets the blood run down on it.

Risach leaves Heinbach and tries to put an end to his life. However, the thought of his late mother keeps him from doing it. After a long mourning he entered the civil service, made a career there, gained reputation and fortune, was raised to the nobility, married a wealthy woman in a marriage of convenience and inherited her after her untimely death. If he gets rich, he gives up his position early. Despite his great reputation in the civil service, he was dissatisfied with his work, because he felt more of the artistic creativity in himself, e.g. B. a builder. Even as a child he liked to be in control of his actions and he was more interested in sensually perceptible processes than abstract systems. Although he is not an artist, he sees himself as a guardian of “pure art” in relation to works that represent “lust and vice”, as they are valued by uncultivated people. As a “priest” he delays “the step of calamity when the art service begins to deteriorate”, and carries “the lamp first when it is supposed to get light again after darkness” (III, 3). He explains to Heinrich that social conditions have become such that more and more people are missing their true essence in the machinery that has developed to satisfy general needs. So he too failed to act according to what “ things only demanded for themselves and what was in accordance with their essence. "

The baron acquires the Asperhof and begins his "the essence of things" activity there. He plants one wall of his house with the roses that bloom every year in all colors as a symbol of calamity and at the same time as an image of overcoming and renewal.

One day Mathilde is standing in front of him in front of the rose wall. There is a tearful reconciliation. Both are alone again after marriages they entered into by convention and after the death of their partners and renew their bond. Mathilde gives Risach, who has remained childless, the younger son Gustav, to whom she has given his first name, for upbringing and purchases the Sternenhof in the neighborhood, which she renovated and furnished with Risach's help. Like Risach's manor, Mathilde's castle is a symbiosis of nature and culture. During a tour of the rooms Heinrich found out: “One could walk along [the suites], be surrounded by pleasant objects, and not feel the cold or the storm of the weather or winter, while one could see fields and forests and mountains. Even in summer it was a pleasure to walk half in the open and half in art here with the windows open ”. Here Risach explains his conception of a redesign to him: “The devices were designed in the manner that we learned from antiquity, [...] but in such a way that we did not imitate antiquity, but manufactured independent objects for the present time with traces of the Learning from times past ”(I, 7).

A lively visit develops between the aged couple, the buried love awakens anew to a summer one, of which Risach declares that she is “ perhaps the clearest mirror ” of “ what human circumstances have to show, ” but marriage would be too painful and for Mathilde would not match their particular relationship history.

The story ends with the reunion of the Heinrichs family and the circle around Risach and Mathilde. With their marriage, Heinrich and Natalie fulfill one of Risach's highest postulates, the justification of a “ fundamentally ordered family life ”, which is currently more necessary than “ upswing, progress, or whatever is called that appears to be desirable. ““ Art, science, human progress, the state rests on the family. “Heinrich and Natalie's happiness is built on the busy life of Heinrich's parents and the hardships and sad experiences of Gustav and Mathilde, their understanding of the children, whose education and support they see as their central task, and with this idyll he ends Novel.

Guiding symbols

With “Post-Summer”, Adalbert Stifter covers two important realism topics, literature and science. The literature is specifically discussed below. "Der Nachsommer" functions as an educational novel, both in terms of scientific matters and character traits. The subject of literature is largely filled with the aspect of love, which will now be discussed further.

If the two love stories are compared with each other, it can be seen that the failure of Risach and Mathilde to live together forms the basis for a harmonious and functioning coexistence for Natalie and Heinrich. The tragedy between Risach and Mathilde is, so to speak, a prerequisite for the happiness of young people. The suppressed love of Mathilde and Risach is not only a basis for living together, but also for the clear and harmonious development of Heinrich and his life path (cf. p. 31 / Edmund Godde). In a letter, Stifter himself explains that "[the love stories] [] in late summer not only [function] as actual love stories, but as a further basis for the bourgeois Bildungsroman" (p. 117 / Werner Welzig).

Leitmotifs accompany the action, so that you can follow the development of the event through the entire story. The three central guiding symbols are the rose, the marble and the cactus.

The Rose

The rose is the symbol of the development of love, or rather the act of love between Risach and Mathilde. The rose appears for the first time in the form of a rose garden in the Heinbach family, the Mathildes family. From then on, this plant accompanies Risach and Mathilde on the most important paths and steps of their mutual love. For example, the rose stands as a symbol of parting and separation, when the promise of an eternal covenant between Risach and Mathilde is destroyed by their parents' objection. The farewell scene takes place on the rose hedge: “She hid her face in the roses before her, and her glowing cheek was even more beautiful than the roses. She pressed her face completely into the flowers and wept so much that I thought I could feel her body trembling ”(Vol. 3, p. 325). The sign of the rose can therefore also be recognized in "late summer" as a "traumatic experience of loss" (p. 233 / Doerte Bischoff). Because through the annual repetition of the withering, Baron von Risach repeatedly experiences the painful feeling of losing something that he has attached his heart to. Because the rose is the most important symbol of love and the link between Risach and Mathilde, the baron owns so many bushes and tries to restore the connection on a more abstract level. Another time the rose stands as a symbol of the union, when Mathilde and Risach meet again in front of the rose hedge that surrounds the Asperhof and now stay together. If only one symbol can be ascribed to the rose, it will be that of love, as Mathilde's words confirm when they meet again, "and you love me too, that's what the thousand roses outside the walls of your house say" (p. 580 / Wilhelm Goldmann Verlag (WGV)). A sign of the constant love of the older couple can also be found in the book, because every year when the roses are in bloom, Mathilde and her family spend a while at the Asperhof. It's something constant, a cycle that repeats itself every year.

The marble

In "late summer" marble is not only seen as an extraordinarily valuable and impressive rock, but also as a symbol of the existence of a relationship between Natalie and Heinrich. It is therefore not surprising that the key scene of their love takes place in the nymph grotto, in which both confess their love in front of the marble figure. First and foremost, everything beautiful is associated with marble in "late summer". One often speaks of the finely curved lines or the light that makes the marble appear beautifully in its full shine. Heinrich also compares Natalie's beauty with a piece of marble. "I looked at Natalie [...] only now did I realize why she was always so strange to me, I recognized it since I had seen my father's cut stones" (p . 368 / WGV). Marble is also used as a symbol of the paternal-friendly bond between Risach and Heinrich, since Heinrich “one day [found] a piece of marble [and] decided [ss] to give this marble to [his] guest friend on his research trips "(P. 171 / WGV)

The Cactus

The cactus stands as a symbol for the love development of Heinrich and Natalie. Heinrich is deeply enthusiastic about the cacti in the greenhouse and one day brings the Cereus peruvianus to Risach's house. The cactus develops almost parallel to the progression of the love affair between Natalie and Heinrich and the closer they are to starting a family, the more perfect the cactus appears. With the wedding and thus the beginning of a family happiness in harmony, the cactus blooms. The blooming cactus thus stands for family happiness.

Definition of happiness

The cactus as the last of the three symbols is seen as a harmony for family happiness , but what exactly is meant by happiness in late summer is defined by Frank Schweizer as follows: “Happiness, which is inexhaustible and therefore essentially heterogeneous compared to everything else, arises from love , from Heinrich's league with Natalie. Not the natural scientist Heinrich, not even his fatherly friend Risach, but the organism of the family and the generations is the real subject of poetry ”(Frank Schweizer). He also describes that “Stifter [s] [] novella characters become happy or unhappy due to his affect theory: those who stick to reason are rewarded and are allowed to marry, those who give in to desire remain without a wife and child. The family is the greatest happiness that can be achieved ”(p. 201; Frank Schweizer).

This theory is confirmed if one looks at the course of the two love stories in late summer . The happiness of the first love story fails because of “desire [to which one] gives in”; Since Risach and Mathilde swore the covenant when they were young and kept it secretly for a longer period, Risach and Mathilde were not granted the happiness of a family and thus of an order (family order). Heinrich and Natalie, however, were sensible in seeking the permission of the families - "My friend, we have assured ourselves of the continuity and the incessantness of our inclination [...] but what will happen now [...] depends on our relatives" (P. 420 / WGV) - and promised to dissolve the covenant if a family member objected, “If one thing says no and we cannot convince it, it will be right […] but we can then no longer see ”(p. 420 / WGV). In this way, the young people can enjoy the happiness of starting a family because they have obeyed the mind and are thus rewarded. With the marriage to Natalie the book ends and thus the aim of the book is reached. The book is a life story that shows a development. Everyone develops, just not in the same direction and with this life path, as it runs in the book, through the influences of the father, Risach, society, the preoccupation with nature and with the love for Natalie, the ideal of Development shown. Since the development novel ends with the marriage to Natalie, one can say that the ideal of development is associated with the happiness of founding a harmonious, loving family and thus creating order in this area. (P. 627 / Stuttgart edition)

Features of the novel

About the environment: The Biedermeier period as a form of romanticism reflects on the individual in the novel, shows private matters and illuminates bourgeois life. After the repression of the Carlsbad Decrees by Metternich , play major political issues aimed at changes in the current situation does not matter. People were satisfied when the state left them alone with their small lives. An early form of disaffection with politics ? The inner emigration ?

About the content: The most important point of the novel is the central theme of education . Education of the heart in the narrower sense, classic education with " body theory, soul theory, theory of thought, moral theory, legal theory, history " and ancient languages, the educational journey , scientific interest and a universalistic approach that ends in a well-meaning amateurism. Science without science? Perhaps this can be explained by the fact that the goal was not knowledge of nature, but self-knowledge. This self-knowledge came about through meaningful occupation. Here, too, the journey was the goal.

On the title: "Post-summer" is the time of the extended summer without its heat, with mild, sunny days, but still without the coolness of the autumn night. In a figurative sense, it is also the time of the mature person who has already passed the height of his life without, however, already being of old age. The term "Indian Summer" falls twice in the novel by the hospitality (as founder the host Risach of the narrator in a remarkable reversal of the relationship is called), this refers to a so its present stage of life, on the other hand the birds enjoy a late summer where they enjoy the freedom one more time before leaving the country in winter.

- Ulrich Greiner explains: […] One surprising day, Mathilde appears and asks his forgiveness. They are both old now - whatever that means, because if you do the math, you will see that both ages must be somewhere around 50. [...] Summing up your late days, Risach says about himself and Mathilde: "So we live happily and steadily, as it were, a late summer without a previous summer."

Names: The founder introduced the names of his main characters very late. Mostly he describes the people by their function: the father, the mother, the sister, the host, the princess, the gardener, the zither player. He carefully approaches the name with the first names of the most important people: Mathilde, Natalie, Gustav, Eustach, Roland and Klotilde. The first-person narrator calls himself Heinrich Drendorf late, his host, Baron von Risach, remains nameless until almost the end, with the exception of hints. Why doesn't Stifter name the characters in his novel? Perhaps it is not so much for him that the readers “get an idea” of the people, but rather of the person's path through life. The winding paths unravel and everything will be fine.

Idealization of love: the novel contains tragic and happy love stories. Nevertheless, love always remains “pure” and chaste, the lovers are shy and “blush” only when thinking of the loved one. A kiss appears as an uncontrolled exuberance of feelings. Calm and (self-) control is the goal of love, not the happiness of emotions. Love is not an everyday occurrence, and lovers do not think about tomorrow, their apartment, their income, and certainly not about the problems that they create for themselves and others through being in love. This applies to both of the novel's central love stories. In this idealized conception of love, the focus is not on the fulfillment of desire, but on personal inner growth in the search for it.

Humor: The novel is not just serious. At some points, Stifter describes cheerful scenes with a wink: Heinrich comes home and has an important personal message to give his family that upsets him inside. “ They were reassured then, and as it was their way, they did not ask me about my reason. “Or Heinrich is traveling with his pretty sister. As soon as they arrive at the inn, the following happens: “ Everyone who could operate an oar or were trained to put on a crampon or use an alpine stick came over and offered their services. "

Roses: Roses are the symbol of love in this novel, and the time from the first buds to full bloom is considered the most beautiful time of the year. Applied to people's lives, the parallel can be drawn to the maturation process, which consists in the full development of the personality.

Collecting: Collecting is a central characteristic of people in "late summer". Whether it is about plants, stones or paintings, every person in the story takes pleasure in this “hobby”. It serves as an exchange of knowledge and an educational maxim, because "[...] in a collection [things] gain in language and meaning [...]". (P. 689 / Stuttgart edition) Collecting is an expression of respect for the things that should come to light. As a result of this activity, the objects gain in importance and are made clear to the reader through the description of the variations and special features. The devotion to the “things” that make up collecting makes people a model for their environment. Adalbert Stifter particularly emphasizes the people who act according to this model in his story, thereby the gardener and the zither player gain importance for the plot. By dealing with the “things” in their work area, they show how successful it can be to show respect and awe for nature and objects of art.

The art: The art plays an essential role in the everyday life of the story. In "late summer" one can find an unusually large number of descriptions of sculptures, paintings and other handicrafts. At the Asperhof there are some restoration sites where old equipment is restored in order to be able to extend the useful life of the works of art. (See p. 92 f. / Stuttgart edition) Because the Baron von Risach is of the opinion that “a veil of oblivion will lie over all works of art that are still there” (p. 109 / Stuttgart edition). The fact that art is described as ephemeral establishes the relationship to human life and nature. Man, nature and art are tightly bound together. Adalbert Stifter lets this fact come to the fore again and again in "late summer", but the reader often only recognizes his comments at second glance. A particularly important main message from Stifter to the reader is the invitation to be more “in awe of things”. (P. 266 / Doerte Bischoff) The "things" include everything that surrounds people. These also include stones, plants or art objects.

Quotes

- “ Doesn't the greater part believe that man is the crown of creation? And don't those who are unable to step out of their ego think that the universe is only the scene of this ego, including the innumerable worlds of eternal space? And yet it should be completely different. "

- “ The master said nothing to this praise, but lowered his gaze to the floor, but my host seemed pleased with my judgment. "

- “ The sea, perhaps the greatest thing that the earth has, I took into my soul. "

- “ I saw peoples and learned to understand and often love them in their homeland. "

- “ No thanks until it's all over. "

- “ When I had come quite a long way out and found myself in a part of the country where gentle hills alternate with moderate areas, farmyards are scattered, fruit-growing stretches across the country, as it were, in forests, the church towers shimmer in between the dark arbor the creeks rushing through the valley and everywhere because of the greater widening that the land gives, the blue jagged band of the high mountains can be seen, I had to think of a stop. "

Quotes about "post-summer"

- Three strong volumes! We believe we are not risking anything if we promise the Crown of Poland to those who can prove that they have selected them without being obliged to act as an art judge. Friedrich Hebbel , 1858.

- If one disregards Goethe's writings and especially Goethe's conversations with Eckermann, the best German book there is: what is actually left of German prose literature that deserves to be read again and again? Lichtenberg's Aphorisms, the first book in Jung-Stilling's life story, Adalbert Stifter's Nachsommer and Gottfried Keller's people from Seldwyla - and that will mean the end of it. Friedrich Nietzsche , Human, All Too Human , 1878.

- Which is why Adalbert Stifter's “Nachsommer” remains one of the greatest novels in the German language. Ulrich Greiner in the time , 2009

Literature (selection)

Text output

First edition: Adalbert Stifter: Der Nachsommer. A story. Pesth: G. Heckenast 1857, 3 vols. 483, 420, 444 pp., Title of vol. 1 lithographed and illustrated.

- Vol. 1. Digitized and full text in the German text archive , Vol. 2. Digitized and full text in the German text archive Vol. 3. Digitized and full text in the German text archive

Historical-critical edition:

- Adalbert Stifter: The late summer. A story. Edited by Wolfgang Frühwald and Walter Hettche. Stuttgart u. a .: Kohlhammer 1997 (Adalbert Stifter: Works and Letters. Historical-Critical Complete Edition. Ed. by Alfred Doppler and Wolfgang Frühwald, Vol. 4.1, 4.2 and 4.3)

- Adalbert Stifter: The late summer. Apparatus. From Walter Hettche. Stuttgart u. a .: Kohlhammer 2014 (Adalbert Stifter: Works and Letters. Historical-Critical Complete Edition. Ed. by Alfred Doppler and Wolfgang Frühwald, Vol. 4,4 and 4,5)

Other editions:

- National research and memorial sites for classical German literature in Weimar (ed.) Stifter's works in four volumes, Der Nachsommer I,

- Adalbert Stifter, The Post-Summer . Novel. With an afterword and selected bibliography by Uwe Japp. Artemis and Winkler, Düsseldorf, Zurich, 2005.

- Hümmeler, Hans (ed.): Adalbert Stifter: Der Nachsommer, Düsseldorf 1949

- Stefl, Max (ed.): Adalbert Stifter: Der Nachsommer. Augsburg 1954

- Jeßing, Benedikt (ed.): Adalbert Stifter: Der Nachsommer, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-15-018352-9

- Adalbert Stifter: Der Nachsommer, Zurich / Düsseldorf 15th edition 2005, ISBN 978-3-538-05200-0 (Winkler Weltliteratur thin print)

- Stifter, Adalbert: The late summer . A story. Wilhelm Goldmann Verlag Munich (vol. 1378/79/80).

Secondary literature

- Doerte Bischoff: Poetic Fetishism. The cult of things in the 19th century. Munich 2013

- Uwe Bresan: Founder's "Rosenhaus". A literary fiction makes architectural history . Alexander Koch, Leinfelden-Echterdingen 2016

- Edmund Godde: Stifter's late summer and Heinrich von Ofterdingen . Investigations on the question of the poetry-historical home of the "post-summer". Diss. Phil. Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn 1960

- Iris Hermann: From crossing the gaze. The gradual manufacture of eroticism in Stifter's “Nachsommer” , in: Traverses. For Ralf Schnell on his 65th birthday . Ed. Iris Hermann and Anne Maximiliane Jäger-Gogoll, Heidelberg 2008 ISBN 978-3-8253-5553-1 pp. 109–118

- Hugo von Hofmannsthal , donor's “Nachsommer” , in: Ariadne. Yearbook of the Nietzsche Society, Munich 1925, pp. 27–35

- Walther Killy , Utopian Present. Founder: “The Post-Summer” , in: ders., Reality and Artistic Character. Nine novels from the 19th century. Munich 1963, pp. 83-103: digitized

- Victor Lange: Founder. Der Nachsommer , in: Benno von Wiese (ed.): Der deutsche Roman , Vol. 2. 1962, pp. 34–75

- Marie-Ursula Lindau: Stifter's "Nachsommer". A novel of restrained emotion . Basler Studies on German Language and Literature, 50. Francke, Bern 1974 ISBN 9783317011211

- Petra Mayer: Between uncertain knowledge and certain ignorance. Narrated knowledge formations in the realistic novel: Stifter's “Der Nachsommer” and Friedrich Theodor Vischer's Auch Eine . Bielefeld 2014

- Mathias Mayer: Der Nachsommer , in: ders., Adalbert Stifter. Telling as recognizing . Reclam, Stuttgart 2001 (= RUB 17627), pp. 145–170 and pp. 257–261 (with bibliography)

- K.-D. Müller: Utopia and Bildungsroman. Structural investigations on Stifter's “Nachsommer” , in: ZfdPh 90, 1971, pp. 199–228

- Chr. Oertel Sjörgen: The Marble Statues as Idea. Collected Essays on Adalbert Stifter's “Der Nachsommer” . Chapel Hill 1972

- Thomas Pohl : Nihilism in Adalbert Stifter's 'Der Nachsommer' and Gottfried Keller's 'Der Grüne Heinrich'. Dissertation online

- Walther Rehm : "Post-Summer". On the interpretation of Stifter's poetry . Munich 1951

- Urban Roedl: Adalbert Stifter in personal testimonies and photo documents. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1965

- Max Rychner : Stifters “Nachsommer” and Witiko , in: ders .: Welt im Wort. Literary essays . Zurich 1949, pp. 181-210

- Arno Schmidt : The gentle monster. A century of "post-summer" , in: ders., Dya na Sore. Conversations in a library , Karlsruhe 1958, pp. 194–229

- Frank Schweizer : Aesthetic Effects in Adalbert Stifter's "Studies". The importance of desire and appropriation in the context of Adalbert Stifter's aesthetic process, differentiated from Gottfried Keller . Peter Lang, Frankfurt 2001. Series: Comparative Literature, 98

- Arnold Stadler : My founder . DuMont, Cologne 2005

- Emil Staiger , Adalbert Stifter, “Der Nachsommer” , in: ders., Masterworks in the German language from the 19th century , Zurich 1943, pp. 147–162

- Werner Welzig (ed.): Adalbert Stifter. The little things scream. 59 letters. Frankfurt 1991, pp. 115-123

- W. Wittkowski, that it will be guarded as a treasure. Founder's "post-summer". A revision , in: Literaturwissenschaftliches Jahrbuch LJb 16, 1975, pp. 73–132

Web links

- The late summer in Project Gutenberg ( currently not usually available for users from Germany )

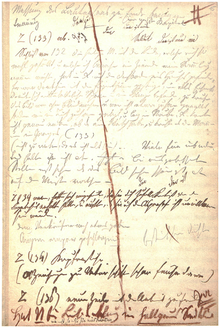

- Adalbert Stifter: The Post-Summer Autograph BSB (Cgm 8072)