Suffrage

The right to vote of the citizens , their right to vote is one of the pillars of democracy and to ensure that the sovereignty of the people is respected. Citizens entitled to vote are commonly referred to as voters , electorates or colloquially , in Switzerland sometimes officially, as electoral people. The right to vote is one of the basic political rights . A distinction must be made between this and the right to vote .

History of the Suffrage

The history of the right to vote can be traced back to ancient times. In the Middle Ages, the forerunners of modern suffrage can be found primarily in the election of representatives to the state assemblies. However, the right to choose is of little importance as an ordering technique. Continuous use of election as a representative ordering technique is found only in England. In the 15th century, the right to vote in England was given legal form and at the same time linked to property. In the 19th century the parliamentary principle spread further and further. In the French Revolution from 1789 and in the German Revolution in 1848 , all male citizens were entitled to vote. In North America there are traces of universal suffrage as early as the 17th century, but without attaining any lasting significance. With the American Revolution and the subsequent federal constitution universal male suffrage is anchored to the central federal bodies in some states. For a long time, however, the regulation of the right to vote was reserved for the individual states, which sometimes tied the right to vote to income or race. The actual implementation of universal suffrage did not take place until the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Democracy in Switzerland has a different origin than the advisory assemblies in monarchies. Since the Middle Ages, meetings of all men in a community have taken place here, in which the authorities were elected and matters were voted on. Such provincial communities have been attested to since the beginning of the Confederation , in Uri since 1231, in Schwyz since 1294 and in Unterwalden since 1309. Every man capable of military service had access to the provincial community regardless of his status.

Before the 20th century, the right to vote in monarchies was often linked to conditions such as status, property, education or tax payments ( census suffrage ), which reduced the electorate to a small part of the total population. In most states, universal suffrage in particular had to be fought for against the authorities who wanted to defend their privileges. The pioneers in the introduction of universal male suffrage include the USA (since 1830), France (1848) and the German Empire (1871).

Comprehensive suffrage prevailed in Europe, especially from 1918 onwards. Often at the same time, but in some countries much later (e.g. Switzerland), women were given the right to vote . The voting age was mostly linked to the legal age of majority of a citizen, which is originally 24 years, then for a long time 21 years and today in many cases 18 years of age. In Austria, the voting age was last lowered to 16 years, the age of majority remained at 18 years.

Whereas for a long time exercising the right to vote was tied to appearing in person before the responsible electoral commission, today, in many countries, travelers and citizens living abroad also have various forms of voting cards (for voting in front of an electoral commission outside the place of residence of the voter) and the Postal voting (sending the completed voting slip by post) in use.

In the course of the implementation of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, the practice, which was partly abandoned and partly still applied in the 21st century, is being criticized by many states of excluding people from the right to vote who are responsible for all their affairs under legal supervision stand (in Germany according to § 1896 BGB ).

Germany

See also: Right to vote in the individual German states until 1918

The elections to the Frankfurt National Assembly in 1848 are the first to be held in Germany under universal suffrage for men (see Federal Election Act (Frankfurt National Assembly) ). Along with Switzerland and France, Germany is one of the first countries in Europe to introduce universal suffrage, albeit for a short time. Otto von Bismarck introduced universal suffrage (for men) in the North German Confederation in 1867 in order to weaken the liberals. He correctly assumed that the broader rural population would vote more conservatively. In the long term, however, this mass suffrage strengthened the opposition Social Democrats . In the German Reich , which was newly founded in 1871 , there was a male suffrage right from the start.

In Prussia , the most important individual state, weighting was different according to the tax revenue of the individual (see three-tier voting rights ). Other German states also had discriminatory rules.

It must be taken into account that in 1871 34% of the total German population were younger than 15 years old (1933 24%, Federal Republic of 1980 18%; Federal Republic of 2017 13.5%). So a voting age of at least 25 excluded a large percentage of the population . So it happened that in 1871 only 20% of the total population were actually allowed to vote.

After the end of the First World War , the Weimar Republic was proclaimed on November 9, 1918 . On January 19, 1919, the election for the constituent national assembly took place. For the first time, women had the right to vote in Germany. At the same time, the active voting age was reduced to 20 years and universal and equal voting rights were introduced in all individual states. In addition, Germany became a parliamentary democracy at that time, as the Reichstag could (indirectly) determine the composition of the government .

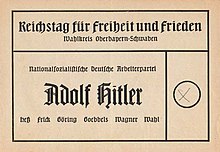

After the establishment of the National Socialist one-party dictatorship , elections no longer had any political significance.

Jews lost their right to vote through the Reich Citizenship Act of September 15, 1935; They were not allowed to participate in the sham election of March 29, 1936 (empty ballot papers were also counted as votes for the NSDAP; the result was 98.8% for Hitler or the NSDAP).

The principles for elections in the Federal Republic of Germany (since 1949) are listed in the Basic Law , details of the election are determined by the Federal Election Act .

- 1945: The age limit for the right to vote is raised from 20 to 21 years.

- 1970: An amendment to Article 38 Paragraph II of the Basic Law reduces the active voting age from 21 to 18 years and the passive voting age to the age of majority; the law amending the federal electoral law of 1972 takes over these adjustments.

- 1974: The age of majority , and thus the age limit for the right to stand, is also reduced to 18 years (in force from January 1, 1975).

- 1995: In Lower Saxony the voting age for local elections is lowered to 16. Other federal states followed.

- 2009: Bremen lowers the voting age for state elections to 16 years. Brandenburg followed in 2011, Hamburg and Schleswig-Holstein in 2013.

Austria

- 1848: Introduction of census voting rights .

- 1873: Reichsrat election reform in the Austrian half of the empire of the monarchy ( Kuria suffrage ): The members of the House of Representatives were elected to four curiae (aristocratic landowners, township, trade and industry, rural communities) on the basis of the census suffrage . Only about 6% of the male population aged 24 and over were eligible to vote; the required annual minimum tax payment was regulated differently in different places and was 10 guilders in Vienna. In the large landowner curia there were also "self-sufficient" women, i. H. Women who represented themselves are entitled to vote.

- 1882: Taaffe's reform of the electoral law : the tax payment for voting was reduced to 5 guilders.

- 1896: Baden's electoral reform created a voting class. (The 5th Curia was the class of male voters from the age of 24.) The members of the first 4 Curiae were allowed to vote again in the 5th Curia; the number of mandates per vote was unevenly distributed between the Curiae.

- 1907: Beck's reform of the electoral law : abolition of the curiae suffrage and introduction of a universal male suffrage (active suffrage: 24 years; passive suffrage: 30 years).

- 1919: After the fall of Austria-Hungary and the law of November 12, 1918 on the form of state and government in German-Austria , women also gained the right to vote.

- 1920: A separate electoral law was created for the election of the constituent National Assembly of German Austria on February 16, 1919. Transition to proportional representation (proportional representation), the v. a. was demanded by the Social Democratic Workers' Party (SDAP) .

- 1923: The active voting age is 20 years, the passive voting age is 24 years.

- 1929: With the reform of the federal constitution , there is also a reform of the electoral law (popular election of the Federal President ). The voting age is increased by one year for the right to vote. You can only be elected from the age of 29.

- 1933 to 1938: corporate state , parliament was dissolved and not reinstated

- 1938 to 1945: part of the German Reich through the “ Anschluss ”

- 1945: With the re-establishment (re-establishment) of the Republic of Austria, the voting rights of 1929 apply again. In the first free National Council election after the end of World War II on November 25, 1945, former National Socialists are excluded from the election (see also National Council election in Austria 1945 ).

- 1968: The voting age is reduced to 19 for the active and 25 for the passive.

- In 1970 and 1992 the National Council election regulations (NRWO) were reformed.

- 2003: The minimum age (then 18 years active, 19 years passive) does not have to be reached until election day (Federal Law Gazette I No. 90/2003). Before that, it had to have been reached on January 1st of the year in which the reference date was.

- 2007: Reduction of the active voting age from 18 to 16 years, simplification of postal voting and voting abroad, extension of the electoral period from four to five years, lowering of the passive voting age from 19 to 18 years (Federal Law Gazette I No. 27/2007 and 28 / 2007). Until 2007, postal voting was only possible for Austrians abroad.

Switzerland

There are democratic traditions in Switzerland that go back to before the French Revolution . In contrast to the post-revolutionary understanding of democracy as a natural right for all people, the old confederates viewed democracy as a privilege that was passed on to male descendants. History therefore differentiates between modern and premodern democracy (Suter 2004). The premodern democracy in Swiss municipalities and cantons was an assembly democracy. All men capable of military service were allowed to participate in the rural communities , there were no restrictions on status or wealth. There was elected and voted and originally also judged. The first rural communities are attested in the 13th century. Eight cantons had a rural municipality, which still exists today in the cantons of Glarus and Appenzell Innerrhoden . The old Confederation was a confederation and not a state.

Universal male suffrage was introduced in the Helvetic Republic from 1798 to 1803, whose constitution incorporated the principles of the French Revolution. The Helvetic Republic was a unitary state with representative democracy according to French ideas. In the following mediation and restoration period , federalism and the old balance of power were restored in the cantons. When the state that still exists today was founded in 1848, universal suffrage for men was reintroduced in Switzerland . The extension to the entire adult population with Swiss citizenship took place with the adoption of the draft for federal voting rights for women on February 7, 1971, after it had been rejected in 1959. 621,109 (65.7%) yes - against 323,882 (34.3%) no votes were received with a participation of 57.7%. Besides Liechtenstein, Switzerland is the only country in which men have given women the right to vote in a referendum. At the cantonal level, Vaud was the first canton to introduce women's suffrage (1959), while the Landsgemeindekanton of Appenzell Innerrhoden was the last to introduce it at the behest of the federal court (1990).

In direct democracy , the right to vote goes hand in hand with the right to vote (e.g. referendum against parliamentary decisions). Swiss voters have more political power than citizens in purely representative democracies.

Great Britain

Under Edward I , knights and citizens were elected to parliament for the first time in 1295. But even in the motherland of modern parliamentarianism, only this small part of the total number of men was eligible to vote for a long time. Just as the origins of the federal German parliamentary system derive from the English model, the origins of German electoral law can also be found in part in England (see majority vote ). In Germany, however, universal (men's) suffrage was introduced quite early on, while in England large parts of the population were excluded because of their financial situation for a much longer period (until World War I). By 1918, around 52% of men were allowed to vote.

Greece

Since the end of the Middle Ages, the Greek peoples had lived within the Ottoman Empire with its absolutist structure. Through the Greek Revolution from 1821 a small part of the Greeks liberated themselves and passed a provisional constitution (σύνταγμα) in the First National Assembly of Epidaurus (A 'Eθνοσυνέλευση Επιδαύρου). In the midst of the chaos of war against the Turkish occupiers, the constitution was largely democratically revised at the Third National Assembly in 1827 and Count Ioannis Kapodistrias was appointed the first governor of the young state. Based on the ideals of the two revolutions that led to the founding of the USA and the French Republic, and with a view to the ancient political legacy, the Greek constitution, which was unusually democratic and liberal for Europe at the time, regulated the state separation of powers (into legislative, judicial and executive ), and in particular the right to vote for (male) citizens. In addition, it was defined who - also among foreigners - could acquire civil rights.

Two years later, on the basis of this constitution, the first democratic election of modern times for the National Assembly was held in Hellas, and thus, contrary to the ideas of the signatory powers England, France and Russia, the First Hellenic Republic was proclaimed and Ioannis Kapodistrias was confirmed in his office as governor. The judiciary was established, and the term βουλή was (re) introduced for the legislative power. It was only through the intervention of the signatory powers in 1832 and the installation of a (German) monarch that the constitution was suspended and absolutism restored. Under popular pressure, a constitution was finally reintroduced in 1844 ( constitutional monarchy ). In contrast, universal suffrage for men was only reintroduced 20 years later.

Netherlands

In the Netherlands, the parliamentary principle had been enforced since about 1866. Those who could show certain “signs of prosperity and ability” were allowed to vote. Under the electoral law of 1896, that was roughly half of the adult male population, and a 1901 change in law and growing wealth made it 68% in the 1913 election. You voted according to constituencies.

In 1917 the constitution was changed and universal male suffrage ( algemeen kiesrecht voor mannen ) was introduced, along with proportional representation. On July 3, 1918, the new electoral law was used for the first time. Women's suffrage followed through a simple change in law in 1919.

restrictions

Historically and currently there are many different restrictions on the right to vote, rules that ensure that residents of a country are not allowed to vote or are not allowed to be elected. Restricting the right to vote to men, which is often history today, as well as allowing only citizens to vote, are fundamental. Likewise, many states do not allow the right to vote abroad. This means that nationals residing abroad will not be allowed to vote.

A guiding principle in discussions on electoral law is the idea that the voter should be "independent". It is common to require a minimum age. In the related discussions, one was often guided by the respective age of majority, even if the development did not always run in parallel. People with certain (intellectual) disabilities, for example if they are under guardianship, are also considered to be not self-employed. Historically, active soldiers and originally even state officials were prohibited from voting or being elected.

Classical-liberal and conservative thinkers understood by an independent voter not least those who had a certain independence through property or education. The right to vote was then linked to property, a certain tax revenue, assets or educational certificates. In the 19th century, some universities were able to appoint MPs.

Some states grant their citizens living abroad the full right to vote, others restrict it (see: Right to vote in the country of origin ).

Some systems refer to a person's behavior when they exclude them from the right to vote. The exclusion can be the result of criminal behavior or, in the narrower sense, politically reprehensible behavior. Convicted offenders cannot or are not allowed to vote for the duration of the sentence or even longer.

Current regulations

A distinction is made between active and passive voting rights: people with active voting rights are allowed to vote, people with passive voting rights can run for candidates and be elected. In public elections in today's democracies, the same group of people usually has both rights at the same time; however, it also happens that the age limit for the right to vote is lower than that for the right to stand as a candidate (see below).

Right to vote

The active right to vote is the right of a person entitled to vote to vote in an election.

The prerequisites for the right to vote are usually:

- Citizenship of the respective country. In local elections, EU foreigners can vote in any EU state.

- Residence in the relevant administrative unit. Citizens living abroad can vote in elections at national level in many countries. Sometimes this is also the case with regional elections, e.g. B. in South Tyrol .

- Minimum age, usually 18 years. In Austria and Malta the minimum age is 16 years, in Greece 17 years. Everywhere else in Europe and in most non-European countries it is 18 years in national parliamentary elections, with exceptions such as B. Indonesia (17 years) and Brazil (16 years).

- The lack of grounds for exclusion. Common grounds for exclusion are certain criminal convictions or some form of care or guardianship that a person is under.

In most countries, voters usually cast their votes at the polling station in the constituency where they are listed on the electoral roll. In Switzerland, over 90% of voters vote by letter. Some countries do not have electoral rolls (e.g. the Netherlands and Latvia). In addition to postal voting, some states have other forms of voting that cannot or do not want to vote in the polling station in their constituency on polling day, such as early voting (common in Scandinavia), voting by a proxy (e.g. in France) or voting in another Polling station (in Germany and Austria possible with a voting slip or voting card, but only in the same constituency in federal and state elections in Germany).

In modern democracies, the principle of universal suffrage is also indispensable. It stipulates that, in principle, every citizen who meets clearly defined minimum requirements (such as voting age) is entitled to vote. Children are not eligible to vote in any state.

According to Art. 29 of the " UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities ", the right to vote must also ensure that people with disabilities have equal opportunities to choose.

Germany

In the Federal Republic of Germany , the elections to the German Bundestag in accordance with Article 38 of the Basic Law (GG) are governed by the democratic electoral principles of a general, direct, free, equal and secret election.

Public elections

The following public political elections are held in Germany:

- the election to the Bundestag (electoral period four years)

- the election to the European Parliament (electoral term five years)

- the election to the state parliament (mostly state parliament) of the respective state (electoral period in Bremen four years, otherwise five years)

- the election to the city council or municipal council , in district municipalities also to the district council , in urban districts usually also to the district council / district parliament (the latter also in the city states), (election period usually five years, in Bavaria six years)

- In most countries there is also the election of the mayor / lord mayor (as well as the district administrator in the case of municipalities belonging to a district ) (election period between five and eight years depending on the country)

- in Bavaria there are district elections

In Germany , the Federal President is not elected by the electorate, but by the Federal Assembly ( Article 54.1 sentence 1 GG).

More choices

There are also elections to the representative assemblies of the social insurance funds ( social elections ).

- In companies and administrations, employees have the right to vote to elect the works council or staff council (if necessary also to represent young people and trainees or represent the severely disabled ).

- Church members are i. d. R. entitled to elect the church bodies ( parish leadership , presbytery).

- Companies in a region elect the general assembly of the regional Chamber of Commerce and Industry and the Chamber of Crafts .

These elections are not “political” elections. The above electoral principles apply, but other conditions may apply. In particular, in elections that do not elect representatives of the population in local authorities , it is often permissible to divide the electorate into status groups. In these cases, one speaks of a functional representative system (example: separate election of student, parent and teacher representatives at school conferences ) in contrast to the egalitarian representative system that is only permitted in “political” elections . In the case of chambers, special electoral rules apply, which lack important democratic principles with election and census voting rights (due to the division of electoral groups with extremely different weights and the chances of success of the votes) (see equality of votes ).

Germans abroad

The Basic Law does not provide any specific regulations for Germans living abroad.

A regulation has been in force since May 3, 2013 ( Federal Law Gazette I p. 962 ), according to which Germans abroad are entitled to vote if they have lived in Germany for at least three consecutive months after reaching the age of 14 and not more than 25 years since moving away have passed. Other Germans abroad may only vote if they “have acquired personal and direct familiarity with the political situation in the Federal Republic of Germany for other reasons and are affected by them”.

Until 1985, Germans living abroad only had the right to vote if they lived abroad as public servants or soldiers on behalf of their employer or if they belonged to the household of such a person. In 1985, the Germans abroad additionally received the right to vote, which continuously at least three months since the enactment of the Basic Law on 23 May 1949 her apartment or other habitual residence in the Federal Republic of Germany had and survived either for less than 10 years abroad, or in a member state of the Council of Europe lived . In 1998 the period was extended from 10 to 25 years and deleted in 2008. Thus, since 2008, all Germans abroad have been actively eligible to vote if they have lived in Germany for at least three months since May 23, 1949. The regulation was declared unconstitutional by the Federal Constitutional Court in July 2012. Since no transitional arrangement was made, there was no legal basis for Germans abroad to vote, which is why they were not eligible to vote from July 2012 to May 2013.

Germans residing in other EU countries can take part in European elections in Germany , provided they do not exercise their right to vote there.

Citizens of other EU countries

In Europe and local elections also citizens of other EU member states who live in Germany are eligible to vote. However, EU citizens are only allowed to cast one vote in European elections, even if they receive two voting notifications (from Germany and from their home country). In accordance with Section 6 (4) of the European Election Act, you may then only exercise the right to vote in one of the two ways. A violation is punishable according to § 107a StGB .

The same applies in other member states due to Article 9 of the Direct Election Act .

Voting age

In most cases, Germans or EU citizens are allowed to take part in elections from the age of 18. The following limits apply:

| area | choice | active | Year of first choice from 16 |

passive | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | Bundestag election | 18th | - | 18th | Until June 9, 1972, the active voting age was 21 and the passive voting age was 25. |

| European elections | 18th | - | 18th | ||

| State of Baden-Württemberg | State election | 18th | - | 18th | |

| Local elections | 16 | 2014 | 18th | ||

| Free State of Bavaria |

State elections District elections Local elections |

18th | - | 18th | |

| State of Berlin | House of Representatives election | 18th | - | 18th | |

| District assembly election | 16 | 2005 | 18th | ||

| State of Brandenburg |

State elections Local elections |

16 | 2014 | 18th | |

| Free Hanseatic City of Bremen |

Citizenship Election City Citizenship Elections |

16 | 2011 | 18th | First election to a state parliament with a reduced voting age. |

| Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg | Citizenship election | 16 | 2015 | 18th | |

| District Assembly Election | 16 | 2015 | 18th | ||

| State of Hesse | State election | 18th | - | 18th | Since 2018, previously the eligibility age was 21 years |

| Local election | 18th | - | 18th | ||

| State of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania | State election | 18th | - | 18th | |

| Local election | 16 | 1999 | 18th | ||

| State of Lower Saxony | State election | 18th | - | 18th | |

| Local election | 16 | 1996 | 18th | ||

| State of North Rhine-Westphalia | State election | 18th | - | 18th | |

| Local election | 16 | 1999 | 18th | ||

| State of Rhineland-Palatinate |

State elections Local elections |

18th | - | 18th | |

| Saarland |

State elections Local elections |

18th | - | 18th | |

| Free State of Saxony |

State elections Local elections |

18th | - | 18th | |

| State of Saxony-Anhalt | State election | 18th | - | 18th | |

| Local election | 16 | 1999 | 18th | ||

| State of Schleswig-Holstein | State election | 16 | 2017 | 18th | It was decided in April 2013 to lower the active voting age to 16. |

| Local election | 16 | 1998 | 18th | ||

| Free State of Thuringia | State election | 18th | - | 18th | |

| Local election | 16 | 2019 | 18th |

SPD, Bündnis90 / Die Grünen and Die LINKE are predominantly in favor of lowering the active voting age to 16 years.

Restrictions and exclusion of voting rights

Every German who has reached the age of 18 and is in possession of the civil rights , which can only be withdrawn as part of a court judgment in serious criminal offenses, is entitled to vote . Exclusion by a judge's verdict can only be granted for life by the Federal Constitutional Court within the framework of the forfeiture of fundamental rights according to Art. 18 sentence 2 GG i. V. m. Section 39 (2) of the Act on the Federal Constitutional Court ( BVerfGG ). This has never happened before in German history.

Illiterate people and people who cannot fill out the ballot paper themselves because of a physical disability, fold it and put it in the ballot box, may use the help of another person for this (Section 33 (2) of the Federal Election Act and Section 57 of the Federal Electoral Regulations, referred to there as an assistant). In this case the voting behavior does not necessarily remain secret. The assistant can also give the affirmation required for postal voting in lieu of an oath . Auxiliary staff are subject to confidentiality. Visually impaired people can also use a voting slip template to fill out the voting slip.

No active (and passive) right to vote in Germany people who

- do not have the right to vote as a result of the judgment,

- are under legal supervision in all matters ( § 1896 BGB ), insofar as a supervisor is not only appointed by interim order to take care of all of their matters ; this also applies if the responsibilities of the supervisor do not include the matters specified in § 1896 Paragraph 4 and § 1905 BGB (postal control and sterilization).,

- in criminal custodial placement in a psychiatric hospital ( § 63 in connection with § 20 of the Criminal Code are located).

A resolution of the Council of Europe of February 22, 2017 speaks out against the practice of excluding people with disabilities from voting . In June 2016, the states of North Rhine-Westphalia and Schleswig-Holstein removed the exclusion of the right to vote because of “support in all matters” from their state and local electoral laws, and in July 2018 the state of Brandenburg followed suit. In Thuringia , the ban is to be overturned in 2019, in Berlin in 2021. In a ruling of February 21, 2019, the Federal Constitutional Court declared the exclusion from the right to vote for people with care in all matters as well as for criminals placed because of incapacity to be unconstitutional.

Austria

Suffrage

In Austria, due to the general, equal, free, direct, secret and personal right to vote, citizens have the opportunity to participate in the following elections if they have reached the age of 16 on election day at the latest ( Art. 26 Para. 1 B-VG , last amended by Federal Law Gazette I No. 27/2007):

- to the state parliament , the parliament of the state of residence,

- to the National Council , the state parliament,

- to the Federal President (§ 4 BPäsWG),

- to the municipal council in accordance with provisions analogous to Art. 26 Para. 1 B-VG ( Art. 95 Para. 2 B-VG); Here, the precise regulation is incumbent on the state laws (see Art. 117 Paragraph 2 B-VG), whereby the explanations may not be drawn more narrowly than in the case of the state election (so-called “homogeneity requirement under the law of elections ”); citizens of other EU member states who live in the municipality are also entitled to vote here;

- in Vienna also on the election of the district representatives for the 23 districts; Citizens of other EU member states living in Vienna are also entitled to vote here, but not in the Viennese municipal council election, because this is also the state election here;

- to the European Parliament for persons who have reached the age of 16 at the latest by the end of the day of the election and who meet certain requirements (§ 10 EuWO in conjunction with § 2 EuWEG)

- to the mayor analogous to the respective municipal electoral law in the federal states in which the mayor is elected directly and not by the municipal council. These are currently Vorarlberg, Burgenland, Tyrol, Upper Austria and Salzburg.

Exclusion from the right to vote

Only a judicial conviction may lead to exclusion from the right to vote or from being eligible for election ( Art. 26 Para. 5 B-VG). Section 22 of the National Council Election Regulations (NRWO) specified the loss of civil rights : "Anyone who has been legally sentenced to more than one year imprisonment by a domestic court for one or more deliberate criminal acts is excluded from the right to vote. This exclusion ends after six months. ... "

In 2007, the provision of § 22 NRWO was examined by the Constitutional Court and found to be constitutional. According to the VfGH, § 22 NRWO is also compatible with the case law of the ECHR on Article 3 of the 1st Additional Protocol to the ECHR (Hirst case): Unlike the provision of British law examined by the ECHR in the Hirst case, § 22 NRWO does not see a general withdrawal of the The right to vote for all convicted prisoners - regardless of the length of the imprisonment imposed and regardless of the type or gravity of the crimes they have committed or their personal circumstances. Convictions of fines, convictions of imprisonment of less than a year and convictions of conditional prison sentences do not result in the exclusion of the right to vote. In addition, Section 44 (2) of the Criminal Code gives the judge the opportunity to conditionally examine the exclusion from voting rights ; to this extent, the Austrian legal system also allows personal circumstances to be taken into account by law. The ECHR, however, saw Article 3 of the 1st additional protocol to the ECHR in the Frodl case violated in 2010 with the provision in § 22 NRWO . As a result of the decision of the ECHR, § 22 NRWO was amended in 2011 so that the range of penalties leading to exclusion from the right to vote was restricted. Only convictions based on certain criminal offenses (e.g. attacks against the state and its supreme organs, criminal acts in elections, criminal acts according to the Prohibition Act) can lead to exclusion from the right to vote if a conviction leads to an unconditional imprisonment of at least one year , Convictions on the basis of other criminal offenses can only lead to exclusion from the right to vote if a conviction leads to an unconditional imprisonment of more than 5 years. In addition, the court must always take into account the circumstances of the individual case when issuing the exclusion from voting rights. A qualified conviction therefore no longer automatically leads to exclusion from voting rights. The exclusion from the right to vote now only ends once the sentence has been carried out.

Section 22 (1) NRWO now reads:

“Anyone who is

criminally punishable by a domestic court on account of a 1st offense after the 14th, 15th, 16th, 17th, 18th, 24th or 25th section of the Special Part of the Criminal Code - StGB;

2. criminal act according to §§ 278a to 278e StGB;

3. criminal act under the Prohibition Act 1947;

4. In connection with an election, a referendum, a referendum or a referendum, a criminal offense committed according to Section 22 of the Special Part of the Criminal Code

to an unconditional imprisonment sentence of at least one year or due to another criminal offense committed with intent If a custodial sentence of more than five years is not conditionally convicted, the court (§ 446a StPO) can exclude the right to vote on the basis of the circumstances of the individual case. "

The mentally ill and mentally handicapped (people with guardians ) are no longer excluded since Section 24 NRWO in 1971 by the VfGH.

Compulsory elective

In Austria there is no compulsory voting in national council, federal presidential and European elections. From 1949 to April 30, 1992, due to the version of Art. 26 Para. 1 of the Federal Constitutional Law (B-VG), elections to the National Council were compulsory due to state laws in the states of Styria, Tyrol and Vorarlberg. From the National Council election in 1986, voting was also compulsory in Carinthia.

In 1992, an amendment to the B-VG abolished the state legislature's ability to order compulsory voting. Thus, for the first time in the 1994 National Council election, voting was no longer compulsory.

In federal presidential elections , voting was compulsory in all federal states until 1982. This compulsory vote was repealed by two changes to the B-VG and to the Federal Presidential Election Act with effect from October 1, 1982. However, Article 60 (1) of the Federal Constitutional Act in conjunction with Article 23 (1) of the Federal Presidential Election Act 1971 allowed the federal states to impose compulsory voting through state law. This meant that voting was compulsory in Carinthia and Styria in 1986 and 1992, in Vorarlberg until 1998 and in Tyrol until 2004. The first federal presidential election without mandatory voting in the entire federal territory took place in 2010.

Voting age

Until 2007, the voting age in Austria was mostly tied to the age of majority . Like the age for them, the voting age has been lowered several times over the decades. All Austrian men and women who have reached the age of 16 on election day and who are not excluded from the right to vote (the age of majority remained at 18) now have the active right to vote in the National Council. This is determined in the Electoral Law Amendment Act 2007, which came into force on July 1, 2007. Austria was the first country in the European Union to introduce this voting age (also for the elections to the EU Parliament) . (Furthermore, this law extended the legislative period of the National Council from four to five years and simplified postal voting.)

Switzerland

In the national elections, every person with Swiss citizenship who has reached the age of 18 is entitled to vote and vote, provided they are not incapacitated due to illness or mental weakness. The women's suffrage was introduced in the 1971st In 1991 the age was lowered from 20 to 18.

Most cantons have a corresponding regulation for cantonal elections . Foreigners who have been settled in Switzerland for a certain period of time have the right to vote at the cantonal level in the cantons of Neuchâtel and Jura , and at the municipal level in all political communities in the cantons of Friborg , Vaud , Neuchâtel and Jura. In the cantons of Basel-Stadt , Appenzell Ausserrhoden and Graubünden , the cantonal legislature leaves the municipalities free to give settled foreigners the right to vote. See also the article on the right to vote for foreigners .

In almost all cantons, the right to vote applies from the age of 18. In 2007, the Landsgemeinde in the canton of Glarus introduced the right to vote for people aged 16 and over. The passive right to vote remains at 18 years of age. In some municipalities there is also a different minimum age for the right to vote.

Both the right to vote for foreigners and the right to vote for minors are viewed as problematic by some political parties, as they do not involve the exercise of civic duties.

See also

Passive suffrage

The passive right to vote (also called eligibility ) is the right to be elected in an election.

Usually the right to stand as a candidate is more strictly regulated than the active right to vote, that is, not everyone who is allowed to vote is allowed to be elected: For example, a voting age of 18 does not necessarily count as a criterion for eligibility.

There are also restrictions, for example, in the event of unsuitability for an office or for re-candidatures (maximum duration of an office). The right to stand for election can be withdrawn from legally convicted offenders (so-called grounds for exclusion ). Corresponding facts can be high treason or treason .

Europe

According to Art. 20 TFEU , every EU citizen has the right to stand as a candidate in local and European elections in his country of residence, if it is not his country of citizenship . This means that EU citizens from other countries can be elected to a local parliament or local authority in both Germany and Austria.

Germany

In Germany, all citizens over the age of 18 enjoy the right to stand as a candidate at local and federal level ( Article 38 (2) sentence 1 of the Basic Law). The age on election day is decisive. At the state level, the age for eligibility is also 18 years. Most recently, in 2018 , Hessen lowered the eligibility age from 21 to 18 years.

In the Federal Republic of Germany, the minimum and maximum age are stipulated for the following offices :

- Federal President : At least 40 years

- Judge at the Federal Constitutional Court : Between 40 and 68 years

- District Administrator : Different regulations in the federal states. In Schleswig-Holstein, for example, at least 27 years on election day . In Bavaria a maximum of 65 years at the beginning of the term of office.

- Mayor : Different regulations in the countries. In Baden-Württemberg, for example, between the ages of 25 and 68 on election day

- For Chancellor can be chosen from 18 years.

- For Bavarian prime minister can be elected from 40 years.

Reasons for exclusion:

- Anyone who has been sentenced to imprisonment of at least one year for a crime by a domestic court automatically loses the right to stand as a candidate for five years ( Section 45 StGB)

- In the case of certain other “political” crimes (for example high treason or treason , election fraud and electoral coercion) , active and passive voting rights can also be withdrawn for two to five years.

Further reasons for exclusion can be found in the article "Exclusion of voting rights ".

Austria

In Austria there is a fundamental right to stand as a candidate with the basic requirement of having the right to vote:

- to the municipal council from the age of 18. Citizens of other EU countries who have been in Austria for more than 5 years (with the exception of Vienna) have the right to stand for election at the municipal level; in Vienna at the district level

- to the district representation (only in Vienna)

- to the Landtag from the age of 18,

- to the Federal Council - sent by the state parliament , therefore also from the age of 18 ( Art. 35 para. 1 B-VG)

- to the National Council from the age of 18 ( Art. 26 Para. 4 B-VG and § 41 NRWO )

- to the Federal President , provided that one has the right to vote for the National Council and has reached the age of 35 at the latest on the day of the election ( Art. 60 Para. 3 B-VG)

- to the European Parliament from the age of 18 ( Art. 23a para. 4 B-VG)

Reasons for exclusion (see also exclusion from voting rights ):

- Anyone who has been legally sentenced by a domestic court for one or more criminal acts to a custodial sentence of more than one year or more than five years (depending on the offense) not conditionally waived; This exclusion from voting ends as soon as the sentence has been carried out (Section 22 NRWO and Section 3 EuWEG ). The previous legal situation was criticized by the European Court of Human Rights as a violation of the European Convention on Human Rights

- Persons who carried out certain activities during the Nazi era (Section 17 in conjunction with Section 18 lit. k Prohibition Act)

Switzerland

In the national elections, every person with Swiss citizenship who has reached the age of 18 is entitled to vote, provided they are not incapacitated due to illness or mental weakness.

Most cantons have a corresponding regulation for cantonal elections . A passive voting rights for foreigners who have settled in Switzerland for a while, know at municipal level, the cantons of Friborg , Vaud , Neuchâtel and Jura . In the cantons of Basel-Stadt , Appenzell Ausserrhoden and Graubünden , the cantonal legislature leaves the municipalities free to give settled foreigners the right to vote. See also the article Right to vote for foreigners .

Some municipalities have a different minimum age for the right to stand for election.

Both the right to vote for foreigners and the right to vote for minors are viewed as problematic by some political parties, as they do not involve the exercise of civic duties.

See also

- Women's suffrage , children's suffrage , family suffrage , felony disenfranchisement

- Voting and voting rights for foreigners

- Election and voting system

- History of the right to vote in Germany

literature

- Margaret Lavinia Anderson: Apprenticeship in Democracy. Elections and Political Culture in the German Empire . Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-515-09031-5 .

- Hedwig Richter : Modern Elections. A history of democracy in Prussia and the USA in the 19th century. Hamburg: Hamburger Edition, 2017.

- Wilhelm Brauneder (ed.): Elections and suffrage . Conference of the Association for Constitutional History in Hofgeismar 1997. (= The State ; Supplement; Booklet. 14). Duncker and Humblot, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-428-10479-X .

- Udo Hermann: The right to vote from an economic point of view in: WISU - das Wirtschaftsstudium Heft 8–9 / 2017, S. 967–973.

- Georg Lutz, Dirk Strohmann: Right to vote and vote in the cantons. Droits politiques in the cantons . Haupt, Bern 1998, ISBN 3-258-05844-X .

- Dieter Nohlen: Suffrage and the party system . (= UTB, vol. 1527). 3. Edition. Leske and Budrich, Opladen 2000, ISBN 3-8252-1527-X .

- Wolfgang Schreiber: Handbook of the right to vote in the German Bundestag. Comment . 7th edition. Heymanns, Cologne inter alia 2002, ISBN 3-452-25141-1 .

- Gustav Strakosch-Graßmann: The universal suffrage in Austria since 1848 . Deuticke, Leipzig and Vienna 1906 ( digitized, PDF )

- Andreas Suter: Premodern and modern democracy in Switzerland . Journal of Historical Research, Vol. 31, No. 2, pp. 231-254. 2004.

- Michael Wild: Equality of choice. Dogma historical and systematic presentation . Duncker and Humblot, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-428-10421-8

- Karl Ucakar : Democracy and the right to vote in Austria. For the development of political participation and state legitimation politics . Publishing house for social criticism, Vienna 1985, ISBN 978-3-900351-47-2 .

Web links

- Information on the right to vote without age limit

- Elections, suffrage and voting systems (private side)

- Text of the Federal Election Act (Germany)

- Tomas Poledna: Right to vote and be elected. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Swiss electoral law regulations

- Austrian Federal Ministry of the Interior: elections and referendums

- Women's suffrage in Germany - January 19, 1919 - First active and passive suffrage for women in Germany

- Comprehensible overview of the electoral system in Switzerland

- Petra Sorge: Not all foreigners are alike. The SPD and the Greens are calling for uniform voting rights. In: Berliner Zeitung . September 29, 2007, accessed June 10, 2015 .

- Brandenburg State Center for Political Education, Who can participate in elections?

Individual evidence

- ↑ ZB: Constitution of the Canton of Valais, Art. 87. VII. Title: Mode of election, eligibility conditions, duration of public office. In: The portal of the Swiss government. Swiss Confederation , March 8, 1907, accessed on November 4, 2019 (as of December 5, 2017).

- ^ Peter Marschalck: Population history of Germany in the 19th and 20th centuries , Frankfurt am Main 1984, p. 173.

- ↑ https://www.destatis.de/DE/ZahlenFakten/GesellschaftStaat/Bevoelkerung/Bevoelkerungsstand/Tabellen/AltersgruppenFamilienstandZensus.html

- ^ In July 1933 the law against the formation of new political parties was promulgated (entry into force in Austria after the Anschluss in March 1938). Thus, for the November 1933 Reichstag election there was only the NSDAP's unified list.

- ↑ a b Kristin Lenz: Bundestag allows 18 to 20 year olds to vote. German Bundestag, accessed December 15, 2018 .

- ↑ Official Gazette Part 1, number 87. In: www.bgbl.de . Bundesanzeiger Verlag GmbH, August 8, 1974, accessed December 15, 2018 .

- ↑ Local electoral rights in Germany: http://www.wahlrecht.de/kommunal/index.htm

- ↑ § 1 Electoral Law. Transparency portal Bremen, accessed on April 15, 2016 .

- ↑ Development of electoral law in Austria from 1848 to today , accessed on January 29, 2018.

- ↑ a b c 2007 electoral reform passed by the Federal Council , Parliamentary Correspondence No. 510, June 21, 2007.

- ^ First democratic constitution of Greece from May 1, 1827.

- ↑ England, France and Russia signed the London Treaty in 1827 as guarantor powers for Greece's independence.

- ↑ Martin Kirsch: Monarch and Parliament in the 19th Century, Monarchical Constitutionalism as a European Constitution - France in Comparison . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1999, ISBN 978-3-525-35465-0 , p. 335 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ JJ Woltjer: Recent verleden , Amsterdam 1992, p. 34.

- ↑ See also Dutch Wikipedia

- ↑ JJ Woltjer: Recent verleden , Amsterdam 1992, pp. 79/81.

- ↑ On the arguments put forward in Liechtenstein for and against the international electoral law, see: Marxer, Wilfried / Sele, Sebastian (2012): International Electoral Law - Pros and Cons and Attitudes of Liechtenstein Citizens Abroad . Working papers Liechtenstein Institute No. 38, Bendern 2012.

- ↑ https://www.maltatoday.com.mt/news/national/85054/vote_16_unanimously_approved#.XUnNL-gzZPY Maltese parliament extends voting suffrage to 16-year-olds

- ↑ https://www.youthforum.org/greece-lowers-voting-age-17 Greece lowers voting age to 17

- ↑ https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/legal-voting-age-by-country.html Legal Voting Age by Country

- ↑ Law of March 8, 1985 (Federal Law Gazette I p. 521)

- ↑ Law of April 20, 1998 (Federal Law Gazette I p. 706 and Law of March 17, 2008 (Federal Law Gazette I p. 394))

- ^ Decision of the Federal Constitutional Court of July 4, 2012 (Ref .: 2 BvC 1/11, 2 BvC 2/11 - decision of July 4, 2012)

- ^ The Federal Returning Officer : Message from the Federal Returning Officer. (PDF) (No longer available online.) In: www.bundeswahlleiter.de . Federal Statistical Office, September 4, 2012, archived from the original on February 27, 2016 ; Retrieved May 13, 2013 .

- ↑ a b German Bundestag, 19th electoral term (ed.): Printed matter 19/8139 - Double voting in the European elections on May 26, 2019 . S. 2 ( bundestag.de [PDF]).

- ↑ Decision (EU, Euratom) 2018/994 of the Council of 13 July 2018 amending the act attached to Decision 76/787 / ECSC, EEC, Euratom of the Council of 20 September 1976 to introduce universal direct elections for members of the European Parliament . 32018D0994, July 16, 2018 ( europa.eu [accessed on September 21, 2019]).

- ↑ http://www.service-bw.de/zfinder-bw-web/deeplink.do?typ=ll&id=1223054&sprachid=deu

- ↑ https://www.kas.de/einzeltitel/-/content/wahlrecht-volljaehrigkeit-und-politikinteresse-1

- ↑ http://www.bravors.brandenburg.de/sixcms/detail.php?gsid=land_bb_bravors_01.c.13807.de

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ http://www.ndr.de/regional/hamburg/buergerschaft253.html ( Memento from February 14, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b The State Returning Officer for Hesse: Results of the 15 referendums in Hesse on October 28, 2018. In: www.statistik-hessen.de . Hessian State Statistical Office , November 1, 2018, accessed on November 11, 2018 .

- ↑ a b Landtag mandate from the age of 18 - amendment of Article 75. In: Hessischer Landtag. Retrieved March 4, 2019 .

- ↑ https://www.kas.de/einzeltitel/-/content/wahlrecht-volljaehrigkeit-und-politikinteresse-1

- ↑ https://www.kas.de/einzeltitel/-/content/wahlrecht-volljaehrigkeit-und-politikinteresse-1

- ↑ Schleswig-Holsteinischer Landtag : Law and Ordinance Gazette for Schleswig-Holstein. (PDF) In: State Parliament Information System Schleswig-Holstein . May 30, 2013, p. 8 , accessed on November 30, 2018 (amendment 1562/2013): “ In § 5 Paragraph 1 [LWahlG Schleswig-Holstein, note d. Ed.] The words "18th year of life" are replaced by the words "16. Year of life " "

- ↑ http://landesrecht.thueringen.de/jportal/?quelle=jlink&query=KomWG+TH+%C2%A7+1&psml=bsthueprod.psml&max=true

- ↑ Leander Palleit: Equal suffrage for everyone? People with disabilities and the right to vote in Germany . German Institute for Human Rights . November 2011, p. 8

- ↑ Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs (BAMS): Study on active and passive voting rights of people with disabilities . July 2016

- ^ Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe: “The political rights of persons with disabilities: a democratic issue”. Document 14268 . 22nd February 2017

- ^ Brandenburg abolishes the exclusion of voting rights. Bundesanzeiger Verlag GmbH, July 4, 2018, accessed on February 22, 2019 .

- ↑ Federal Anti-Discrimination Agency: Exclusion of the right to vote ( Memento from December 6, 2017 in the Internet Archive ). August 9, 2017

- ↑ Press release of the Federal Constitutional Court :: Exclusions from voting rights for those under care in all matters and criminals placed because of incapacity to vote unconstitutional. Retrieved February 21, 2019 .

- ↑ a b VfGH September 27, 2007, B1842 / 06.

- ↑ Hirst v. The United Kingdom (No. 2), judgment of October 6, 2005.

- ↑ a b Frodl v. Austria , EGMR 20201/04

- ↑ Electoral Law Amendment Act 2011 - adopted changes Help.gv.at, accessed on June 23, 2017

- ↑ Decree of September 28, 2011 on the 2011 Electoral Rights Amendment Act and the Act on the Amendment of the Criminal Records Act 1968 BMJ 90022S / 2 / IV / 11

- ↑ VfGH Slg 11.489 / 1987

- ↑ a b c Home Office FAQ

- ↑ Federal Law Gazette No. 470/1992

- ↑ Federal Law Gazette No. 354/1982 , Article IZ 2

- ↑ Federal Law Gazette No. 355/1982 , Article IZ 23

- ^ Austrian National Council : Federal Law Gazette for the Republic of Austria. (PDF (signed)) Article 1, point 7. In: Rechtsinformationssystem des Bundes . Federal Ministry for Digitization and Business Location , June 29, 2007, p. 3 , accessed on November 30, 2018 (Electoral Rights Amendment Act 2007 (NR: GP XXIII RV 88 AB 130 p. 24. BR: 7686 AB 7697 p. 746.)): " All men and women who are Austrian citizens, have reached the age of 16 on the day of the election and are not excluded from the right to vote are entitled to vote. "

- ↑ Federal Constitution of the Swiss Confederation

- ↑ Passive suffrage. German Bundestag (bundestag.de), accessed on August 27, 2017 .

- ↑ Art. 54.1 sentence 2 GG

- ↑ §§ 3 Paragraph 1 and 4 Paragraph 3 BVerfGG

- ↑ Section 46 (1) of the municipal code for Baden-Württemberg

- ↑ Art. 44, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution of the Free State of Bavaria . In: www.gesetze-bayern.de . Bavarian State Chancellery, December 15, 1998, accessed January 25, 2019 .