Koenigstein Fortress

The Königstein Fortress is one of the largest mountain fortresses in Europe and is located in the middle of the Elbe Sandstone Mountains on the Table Mountain of the same name above the town of Königstein on the left bank of the Elbe in the district of Saxon Switzerland-Eastern Ore Mountains ( Saxony ).

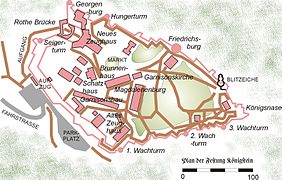

The 9.5 hectare rock plateau , which, according to broken fragments, was discovered as early as the Bronze Age in 1100 BC. Chr. Was inhabited, located 240 meters over the Elbe and testifies with over 50 partly 400 year old buildings from the military and civilian life at the fort. The rampart of the fortress is 1,800 meters long and has walls up to 42 meters high and sandstone walls. In the center of the facility is the 152.5 meters - second deepest castle fountain in Europe after the fountain in the Reichsburg Kyffhausen .

Building history of the fortress

Probably the oldest written mention of a castle on the Königstein can be found in a document from King Wenzel I of Bohemia from 1233, in which a "Burgrave Gebhard vom Stein" is mentioned as a witness. The medieval castle belonged to the Kingdom of Bohemia . The first full name “Königstein” was given in the Upper Lusatian border document of 1241, which Wenzel I sealed “in lapide regis” ( Latin : on the king's stone). In this document, the demarcation between the Slavic Gauen Milska ( Upper Lusatia ), Nisan (Dresden Elbe valley basin ) and Dacena (Tetschner area) was regulated. Since the Königstein was to the left of the Elbe, it was independent of the three districts mentioned. As part of the Kingdom of Bohemia, the more intensively the Elbe was used as a trade route, the more intensively the Elbe was used as a trade route, on behalf of the Bohemian kings, it was expanded into a permanent place dominating the north of their possessions and outpost of the strategically important Dohna Castle in the neighboring Müglitztal .

After the king and later emperor Charles IV had the castle Eulau in Jílové u Děčína, which dominates the southern area, destroyed by citizens from Aussig in 1348 , he stayed on the Königstein from August 5 to 19, 1359 and signed shipping privileges. The castle was pledged several times over the next 50 years, including those of Winterfeld and Donins . Since the latter family belonged to the enemies of the Margrave of Meißen , they finally conquered the castle in 1408 during the Dohna feud, which had been going on since 1385. But it was not until April 25, 1459, with the Treaty of Eger, that the Saxon-Bohemian border and thus the Transfer of the Königstein to the Margraviate of Meißen was determined. In contrast to other rock castles in Saxon Switzerland, the Königstein was still used for military purposes by the Saxon dukes and electors . The Königstein remained an episode as a monastery . Duke George the Bearded , a staunch opponent of the Reformation , founded a Coelestine monastery on the Königstein in 1516 , the monastery of the praise of the miracles Mariae , which was closed again in 1524 - after the death of Duke George, Saxony became Evangelical .

The late medieval castle

There was probably a stone castle on the Königstein as early as the 12th century. The oldest structure still in existence today is the castle chapel built at the turn of the 12th and 13th centuries. The outer walls of a residential tower-like building on a square floor plan, which have been preserved in the main wing of the Georgenburg, date from the 14th century. A courtyard completed the small complex.

This castle from the time of Charles IV was extended to the south by Duke George the Bearded around 1500 with a wing and stair tower, which has also been preserved in the current building.

In the years 1563-1569 the 152.5-meter-deep well was the rock within the castle sunk - until then the occupation of the Kingdom stone was on water from cisterns dependent and rainwater. During the construction of the well, in addition to the sunk rock, an amount of water of eight cubic meters had to be removed from the shaft every day.

Expansion into a fortress and an electoral pleasure palace

Between 1589 and 1591/97, Elector Christian I of Saxony and his heirs had the castle expanded into the strongest fortress in Saxony. The electoral kit master Paul Buchner , who also built other court buildings and fortifications for Christian I, was in charge. Table Mountain, which was still quite rugged until then, was closed off all around with high walls with parapets and round observation towers. As a fortress determined by the terrain, the complex was rather untypical for the Renaissance . The Strasbourg fortress building theorist Daniel Specklin was primarily concerned with this type of building .

As a new building, the gatehouse with its three-wing facade receding over the new fortress gate was built on the Königstein, and as a connecting structure between the older Georgenburg and the new gatehouse, the weir to defend the gate. The gatehouse, built from 1589 to 1591, consisted of a central wing over a newly created driveway as the main entrance to the fortress and two angled wings. Two basement levels extended under the gatehouse, the upper one of which was the new entrance gate, which was higher than it is today. The front fortress portal has not been preserved, unlike the rear portal by Paul Buchner with its rustic cushion frame. In 1591 the anti-fire weir was built, which required large substructures to close a crevice in which five casemates with loopholes for cannons were built. The gatehouse and defense weir were to expand the space for accommodating the electoral court on the upper floors. Here rooms were provided for the electoral couple and high officers, which were equipped with chimneys as early as 1590.

Furthermore, from 1589 to 1591 two pleasure houses were built as central buildings. The Christiansburg (today: Friedrichsburg) and the pleasure house on the king's nose. Christian I had both buildings built so that celebrations could also be held here. The Christianusburg has casemates in the basement with notches for the use of firearms and ballrooms on the two upper floors. Today it is preserved as a baroque reconstruction.

For military purposes, Paul Buchner built the old armory in 1594 and the guard house, today the old barracks , in 1598 .

In 1605 the old castle in the north was rebuilt and adapted to the new buildings in the south above the gate. The building received new dwelling houses, vaults on the ground floor and a stone arcade following the older Wendelstein. The building was only inaugurated under Elector Johann Georg I in 1619 and was given the name Johann-Georgenburg.

Behind the gate, the Magdalenenburg was built as a free-standing, larger pleasure palace on an elongated floor plan from 1622 to 1622 , and in 1631 the Johannissaal as a ballroom above the gateway.

The fortress of the baroque period

The time after the Thirty Years' War can be seen as the second construction phase.

To improve the defense, Wolf Caspar von Klengel built the Johann Georgen bastion in front of the Georgenburg from 1667 to 1669 .

On the area of the Romanesque castle chapel, the St. George's Chapel was built under Duke George the Bearded as early as 1515 , next to which a monastery was to be established. It was rebuilt in 1591 by Paul Buchner the Elder and in 1631 by his son (roof cornice) and again changed and refurbished (tower, roof, altar, pulpit) by Wolf Caspar von Klengel from 1671 to 1676.

The fortress entrance, which was lowered between 1729 and 1735, then received the two works presented in order to better protect the entrance.

From 1722 to 1725, at the request of August the Strong , Böttcher and Küfer built the large Königstein wine barrel with a capacity of 249,838 liters in the Magdalenenburg cellar . The cost was 8,230 thalers, 18 groschen and 9 pfennigs. The barrel, which was only once completely filled with country wine from the Meißner Pflege, had to be removed again in 1818 because it was dilapidated.

Adjustments in the 19th century after the court was abandoned

Even after the expansion in these periods of time, conversions and new buildings were made on the spacious plateau . The Johannissaal, built in 1631, was converted into the New Armory in 1816. In 1819 the Magdalenenburg was converted into a provisions magazine that was fortified from being shot at. The old provisions store was set up as a barracks. The treasure house was built from 1854 to 1855. After the fortress was incorporated into the fortress system of the new German Empire in 1871 , battery walls with eight gun emplacements were built between 1870 and 1895 , which should have served as an all-round defense of the fortress in the event of an attack, which never occurred. This was also the last extensive construction work on the fortress.

Interior of the fortress church, which was redesigned by Wolf Caspar von Klengel from 1671 to 1676

Military importance of the fortress

The fortress played an important role in the history of Saxony , albeit less through military events. The Saxon dukes and electors used the fortress primarily as a safe haven in times of war, as a hunting and pleasure palace, but also as a feared state prison. The actual military importance was rather minor, although generals like Johann Eberhard von Droste zu Zützen (1662-1726) commanded it. During the Seven Years' War , Elector Friedrich August II was only able to watch helplessly from Königstein as his army surrendered to the Prussian army at the foot of the Lilienstein on the other side of the Elbe right at the beginning of the war in 1756 . The commandant of the fortress had been Lieutenant General Michael Lorenz von Pirch from the Electorate of Saxony since 1753 . The battle at Krietzschwitz took place in front of their gates in August 1813 , an important preliminary decision of the Battle of Kulm and the Battle of the Nations near Leipzig . Later commanders were Lieutenant General Karl (1767–1838) and Konstantin von Nostitz-Drzewiecky (1786–1865).

In October 1866, the Prussian Major General Alexander von Rohrscheidt (1808-1881) was appointed in command of the fortress, and in 1870 the Prussian Major General Louis von Beeren (1811-1899) took over. The Prussians then handed over the command to the Saxon Major General Bernhard von Leonhardi (1817–1902). The military importance was lost with the development of extensive artillery at the end of the 19th century. The last commandant of the Königstein Fortress was Lieutenant Colonel Heinicke until 1913. In times of war the fortress had to house the Saxon state reserves and secret archives. In 1756 and 1813, Dresden's art treasures were also stored on the Königstein. The fort's extensive casemates were also used for such purposes during World War II .

The fortress was never taken, it had too much of a deterrent reputation after the expansion by Elector Christian I. Only the chimney sweep Sebastian Abratzky climbed the vertical sandstone walls in a crevice in 1848. The Abratzky chimney named after him (difficulty level IV according to the Saxon difficulty scale ) can still be climbed today. Since it is forbidden to climb over the wall, you have to abseil again below the closing wall.

The fortress as a prison

Until 1922, the fortress was the most famous state prison in Saxony. During the Franco-Prussian War and both World Wars , the fortress was also used as a prisoner-of-war camp. From 1939 to 1945 Polish, French, British, Dutch and American prisoners of war were interned, with the camp being run as Oflag IV-B. After the Second World War, the Red Army used the fortress as a military hospital . From 1949 to 1955 it was used by youth welfare in the GDR as a so-called youth work center to re-educate offenders who did not fit into the image of socialist society.

Prisoners at Königstein Fortress (selection)

- Nikolaus Krell 1591–1601, Electoral Saxon Chancellor

- Wolf Dietrich von Beichlingen 1703–1709, electoral Saxon grand chancellor and high court marshal, for insulting majesty

- Franz Conrad Romanus 1705–1746, Mayor of Leipzig

- Johann Friedrich Böttger 1706–1707, co-inventor of European porcelain alongside Tschirnhaus

- Johann Reinhold von Patkul 1706–1707, Livonian statesman

- Karl Heinrich Graf von Hoym 1734–1736, Electoral Saxon Cabinet Minister, committed suicide in his cell

- Friedrich Wilhelm Menzel , 1763–1796, Saxon civil servant and betrayer of state secrets

- Bernhard Moßdorf 1831–1833, Saxon lawyer and author of a representative draft constitution

- Michail Alexandrowitsch Bakunin 1849–1850, Russian anarchist and revolutionary

- August Bebel 1872–1874, German politician, SPD chairman

- Thomas Theodor Heine 1899, caricaturist and painter

- Frank Wedekind , 1899–1900, writer and actor

- Henri Giraud 1940–1942, French general, managed to escape from the fortress

- Gustave Mesny 1940–1945, French major general

- Augustín Malár 1944–1945, Slovak general

The fortress as an open-air museum of military history

On May 29, 1955, the Ministry of Culture of the GDR took over the Königstein Fortress and declared it a museum . In the following decades, despite great organizational difficulties, the following buildings could be made usable: Old Armory, New Armory, Brunnenhaus, Treasury, Old Barracks, Georgenburg, Magdalenenburg, Friedrichsburg, ammunition loading systems for batteries VII and VIII as well as war barracks I and III.

In the 1960s, the GDR converted a war powder magazine, the Saalkasematte, into a bunker for civil defense : an emergency power generator, ventilation, waterworks and gas-tight doors were installed. The “hall” was structurally divided into work rooms. Between 1967 and 1970, an elevator approved for 42 people was installed at the foot of the access road. This elevator has two intermediate stations (adventure restaurant and casemates) and, as a freight elevator, can transport vehicles up to 4.5 tons.

In 1991 the Königstein Fortress became the property of the Free State of Saxony and has been extensively renovated since then. In 2005, a second elevator was built on a vertical outer wall of the fortress, which transports a maximum of 18 passengers in a panoramic cabin to a height of about 42 meters. There is a covered waiting area at the foot. The state of Saxony provided 1.7 million euros for the construction. The panorama elevator went into operation at Easter 2006. Between 1991 and 2017, the Free State of Saxony invested around 66 million euros in the renovation and expansion of Königstein Fortress.

The museum has been operating as a GmbH since 2000, and has had non-profit status since 2003 . Since it opened, an average of half a million visitors have come to Königstein Fortress every year. In 2019, a third of them came from Poland and the Czech Republic. The fortress presents itself to visitors as a military-historical open-air museum with numerous interior, permanent and special exhibitions. Among other things, the Military History Museum of the Bundeswehr Dresden is present in the two arsenals with exhibitions of military history.

| Year (s) | Visitors |

|---|---|

| 1955-2005 | 25,000,000 |

| 1992 | 467.136 |

| 1993 | 538.066 |

| 1994 | 591.150 |

| 1999 | 592.026 |

| 2000 | 649.021 |

| 2001 | 637,582 |

| 2009 | 487,000 |

| 2010 | 446,000 |

| 2011 | 485,000 |

| 2012 | 478,000 |

| 2013 | 465,000 |

| 2014 | 510,600 |

| 2016 | 493.200 |

| 2017 | 476,500 |

| 2018 | 498,000 |

| 2019 | 507.458 |

In 2018 the western development and in 2019 the Magdalenenburg will be renovated.

A new permanent exhibition has been on view at Königstein Fortress since May 1, 2015. Under the title "In lapide regis - On the King's Stone", it tells the almost 800-year history of the fortress from its beginnings in the Middle Ages to the present for the first time. The exhibition in the gatehouse and the strike weir comprises 33 rooms, some of which are accessible for the first time.

Annual event highlights at Königstein Fortress are the Carcassonne fan meeting in February, the historical spectacle “The Swedes conquer Königstein” in early summer (the occasion is the year 1639 when Swedish troops moved from Pirna via Königstein to Bohemia; 300 uniform groups from different federal states provide on the fortress with around one hundred white tents represents a historical field camp), the sports and outdoor event "Fortress Active!" in summer and the historical-romantic Christmas market in Advent.

literature

- Königstein area, Saxon Switzerland (= values of the German homeland . Volume 1). 1st edition. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 1957.

- Friedrich August Brandner: City and Fortress Königstein. A historical compilation . Lauenstein / Pirna 1842 ( digitized version ).

- Balthasar Friedrich Buchhäuser: The Chur-Saxon fortress Königstein . 1692 ( digitized version ).

- Ingo Busse: The fountain on the Königstein. in: Sächsische Schlösserverwaltung (Ed.): Yearbook 1994. Dresden 1995, pp. 155–170

- Fortress Königstein GmbH (Ed.): In Lapide Regis - On the King's Stone. Catalog edition for the permanent exhibition on the history of the Königstein. Königstein 2017 ISBN 978-3-00-057363-7

- Helmuth Gröger: Castles and palaces in Saxony . Verlag Heimatwerk Sachsen, Dresden, 1940, article on the Königsbrück Fortress with illustration on page 146.

- Christian Heckel: Historical description of the world-famous Vestung Königstein, Worbey at the same time, To explain the same, something from the old Dohna Castle in Meissen is traded . Magdeburg 1737 ( digitized ).

- Gabriele Hoffmann: Constantia von Cosel and August the Strong, the story of a maitress . Verlag Bastei Lübbe ISBN 3-404-61118-7

- Albert Klemm: History of the mountain community of the Königstein Fortress . Leipzig 2014.

- Manfred Kobuch: When did the first documentary mention of the Königstein in Saxon Switzerland date? In: Castle research in Saxony. Special issue for the 75th birthday of Karlheinz Blaschke . Beier & Beran, Langenweißbach 2004.

- Richard Steche, Cornelius Gurlitt : Descriptive representation of the older architectural and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony . Meinhold, Dresden 1882–1923. Booklet: Pirna Official Authority. 1882, pp. 34–43 ( digitized version )

- Angelika Taube: Königstein Fortress . Edition Leipzig, 2014, ISBN 978-3-361-00698-0 .

- Angelika Taube: Königstein Fortress . In: Saxony's most beautiful palaces, castles and gardens . tape 3 . Edition Leipzig, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-361-00510-8 .

See also

Web links

- Internet presence of the Königstein Fortress gGmbH

- Königstein Fortress Association

- Military History Museum of the Bundeswehr, Königstein Fortress branch

- The ascent of the Königstein Fortress by Sebastian Abratzky - told by himself , comment on this

- Service regulations for the Königstein Fortress from 1828

- Reconstruction drawing (not scientifically proven)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Sensation on the Königstein, Sächsische Zeitung, Pirna edition, April 15, 2016.

- ↑ a b The results of the building research in the years 2012–2014 in: Hartmut Olbrich: Die Westbauung auf dem Königstein. Building and functional history in transition. In: In Lapide Regis - On the King's Stone. Catalog edition for the permanent exhibition on the history of the Königstein. Königstein 2017, pp. 37–47.

- ↑ Olbrich 2017, pp. 37–39.

- ↑ Sebastian Fitzner: Memory, memory value and building instructions. The architectural representations of Daniel Specklin in the context of fortress construction in the early modern period. In: Jülicher Geschichtsblätter 74/75 (2006/07), pp. 65–92.

- ↑ Olbrich 2017, pp. 39–41.

- ↑ The new dating based on dendrochronological studies according to: Olbrich 2017, p. 42.

- ↑ Rehabilitation of the fortress is expensive , Sächsische Zeitung (Pirna edition) from February 15, 2018.

- ↑ Visitor magnet and building site . Dresdner Latest News from January 11, 2011.

- ↑ a b Sächsische Schlösserverwaltung (Ed.): Yearbook 1993. , Dresden 1994, p. 50

- ↑ Sächsische Schlösserverwaltung (Ed.) Yearbook 1994. , Dresden 1995, p. 51

- ↑ a b Sächsische Schlösserverwaltung (Ed.) Yearbook Volume 8 (2000). , Dresden 2001, p. 156

- ^ Sächsische Schlösserverwaltung (Ed.) Yearbook Volume 9 (2001). , Dresden 2002, p. 135

- ↑ a b Fewer and fewer visitors to Königstein Fortress. In: Free Press. February 10, 2011

- ↑ Königstein Fortress wants to renovate the gatehouse. In: Saxon newspaper. (Pirna edition) February 10, 2012.

- ↑ The fortress is reloading. In: Saxon newspaper. (Edition Pirna) 2/3 February 2013.

- ↑ Fortress takes Pirna under fire. In: Saxon newspaper. (Edition Pirna) February 13, 2014.

- ↑ Königstein Fortress shows its history from May - visitor growth in 2014. In: Dresdner Latest News. February 6, 2015.

- ↑ a b Fortress loses visitors. In: Saxon newspaper. (Edition Pirna) February 13, 2018.

- ↑ a b Dresdner Latest News from January 25, 2019 p. 22

- ↑ Plus visitor numbers at Königstein Fortress . In: Free Press . February 6, 2020 ( online [accessed February 7, 2020]).

Coordinates: 50 ° 55 ′ 8.5 ″ N , 14 ° 3 ′ 24.2 ″ E