Hambach Festival

The Hambach Festival was held from 27 May to 30 May 1832 at the Hambach Castle and near Hambach and in Neustadt an der Haardt (now Neustadt on the Wine Route) in the then to the Kingdom of Bavaria related Rheinpfalz instead. It is considered to be the climax of the bourgeois opposition during the Restoration and at the beginning of the pre-March period . The demands of the festival participants for national unity , freedom and popular sovereignty had their roots in the resistance against the restorative efforts of the German Confederation .

The Hambach Festival should be seen in connection with other events, such as the Wartburg Festival (1817), the French July Revolution (1830), the Polish November Uprising (1830/31), the Belgian Revolution (1830/31), the Gaibacher Festival , which started at the same time ( May 27, 1832), the Sandhof Festival (May 27, 1832), the Nebelhöhlenfest (early June 1832), the Wilhelmsbader Festival (late June 1832), the Frankfurt Wachensturm (1833) and finally the March Revolution (1848 / 49).

prehistory

Political and legal environment

After the conquest of the left bank of German territory by French revolutionary troops in the 1790s, legal protection in 1801, was among today's Palatinate to the French Republic . The Palatinate population was therefore familiar with the ideas of the Revolution, Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité (freedom, equality, brotherhood). With the defeat in the Wars of Liberation , Napoleon Bonaparte's era came to an end. At the Congress of Vienna from 1814 to 1815, the winners divided up Central Europe and drew new borders. The Rhine district was added to the Austrian Empire , and a year later, in the Treaty of Munich , it was again ceded to the Kingdom of Bavaria. Under Bavarian administration, it was later renamed to Rheinpfalz to distinguish it from the Bavarian Upper Palatinate . The civil liberties, which were taken over from the Revolution with the occupation by France , were partially preserved. However, the practical implementation repeatedly led to conflicts between the citizens of the Rhineland Palatinate and the Bavarian central authority. The restorative conditions of the Metternich era from 1815 onwards resulted in a resigned retreat among the population; They mostly avoided conflicts with the authorities and behaved in a conservative manner .

Educational civic aspiration

The rising bourgeoisie could afford education. Better off citizens sent their offspring to grammar schools and then to universities . In addition, the emergence of secondary schools opened up improved education for the less well-off middle class. Many students took part in the wars of liberation against Napoleon. They joined for this in free corps . Instead of the king, the fighters of the Freikorps swore their oath to the fatherland. After the common struggle, some of the returning students founded fraternities because they felt committed to the goal of "freedom and independence of the fatherland" and saw the country teams that had grown according to their regional origin as no longer up to date. The first fraternity to adopt this idea was the original fraternity founded in Jena in 1815 . Launched by the Jena student body aligned Wartburgfest resulted in 1817 in the Thuringian town of Eisenach students from almost all the small states of the German Confederation together. The boys raised on the hard demands, which ranged from national unity, freedom of speech and press freedom on civil rights up to the elimination of tariffs, trade barriers and different weights and measures. The movement was accompanied by the liberal press law of Saxony-Weimar , which allowed the press to convey the thoughts that had arisen to the public.

The Karlovy Vary resolutions of September 20, 1819 formed the basis for the ban. This urged the primitive fraternities to dissolve themselves on November 26, 1819 and led to the persecution of demagogues . As a result, the students joined already existing country teams, founded corps or continued to run the fraternities underground. The students, who have been referred to as “traveling scholars ” since the Middle Ages and who had special rights such as carrying arms because of their wandering, nonetheless spread their demands among the people on their travels between home and the university. After completing their studies, they went into society in the years after 1815 and passed their ideas on to the following generations. The violence and injustice that the youth experienced led to the ideals of unity, freedom and the desire for an arbitrary constitution spreading to the older generation. The co-organizer, speaker and newspaper editor Johann Georg August Wirth had become part of the student movement during his studies, as an example for other participants in the Hambach Festival .

Economic Environment

The beginning of early industrialization increasingly influenced the living conditions of the population and, in part, led to the simultaneously developing pauperism . The authorities from Bavaria disadvantaged the economy of the Palatinate through high customs and tax duties . The taxes were two to four times as high as in "Altbayern". The incorporation into the Bavarian-Württemberg customs union founded in 1828 on December 20, 1829 facilitated cross-border trade within this customs union, but the exchange of goods with small states in other customs associations became more difficult. The tariff surcharges on wine and tobacco, the region's main export products, increased prices. The Frankfurt literary and Hambacher Fest participant Johann Wilhelm Sauerwein wrote in September 1831: “ Germany is still a large forest, but full of barriers, and barriers are the most productive trees for princes. "

In 1829 food prices rose after a bad harvest. The need in the population was exacerbated by the severe winters around 1830 as well as the poor grape harvest and the moderate grain harvest of 1831. As a result, the prices of basic food rose by more than a third between 1829 and 1832. The sufferers were forced, for example, to illegally cut wood in the forest. The scope can be seen in the number of court hearings. The authorities charged almost a fifth of the regional population with forest offenses .

Revolutionary times

The first encouragement to change came from France. At the end of the French July Revolution of 1830 , King Charles X of France abdicated and fled into exile in Great Britain . He was succeeded by Louis Philippe of Orléans , who had received the crown from the hands of Parliament, which earned him the nickname "Citizen King". The establishment of the new king by the people strengthened the liberal movements in Europe. The spark jumped over to the Netherlands in August . In the Belgian Revolution of 1830/31 a provisional bourgeois transitional government proclaimed the sovereignty of Belgium. The national struggle for independence, at the end of which Belgium separated from the Netherlands as an independent kingdom with a liberal constitution and a strengthened parliament, spread from Brussels . Furthermore, in the November uprising of 1830/31, the Poles were pushed towards national unity and independence. Since the Congress of Vienna, part of the country had been given over to Russian authorities. The Russian policy in the so-called “ Congress Poland ” led to violent unrest, which was led by the Polish military. Russia under Tsar Nicholas I intervened militarily. The resistance did not hold up and forced the insurgents abroad, where they asked for asylum and were granted in France.

Overarching enthusiasm

The Poles moved through Germany into French exile. The direct route there led past the Free Federal Capital Frankfurt . The holy alliance between the Tsarist Empire, the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia prevented the German states from becoming involved on the part of the Poles. Prussia and the German Confederation did not intervene in the situation in Poland because they feared that their own Polish subjects might rebel. The main part of the German population was of little interest in the fate of the Poles, but the liberal citizens fraternized with the Polish refugees whom they admired for the "freedom struggle". They committed themselves to the foreigners with monetary and material donations.

The concentration of the population on foreign countries was not least due to press censorship, as reporting on domestic affairs was prevented. The extensive reporting on the neighboring countries increased. This led to interest, rapprochement and approval for the idea of French liberalism and, as in France itself, developed more and more into a radical form. The new elections of the Bavarian state parliament in December 1830 brought the Liberals successes. In Munich the students were enthusiastic about it in public. The joy turned into turmoil. The Bavarian King Ludwig I took this as an opportunity to close the university, carry out arrests and tighten press censorship on January 28, 1831. The opposition in the Chamber then abolished these press regulations. The still valid, more liberal constitutional rights in the Rhineland-Palatinate area caused numerous old Bavarians to relocate at this time .

Due to the aforementioned conditions, an opposition made up of early liberal, educational, property-owning and urban-bourgeois forces formed in Germany as well. The revolutions abroad encouraged them to revolt against the restoration-oriented power structure in the German Confederation.

The party

Overview of important festival participants

| Guest of honor: |

|

Carl Ludwig Börne : writer, wrote for the Allgemeine Zeitung and was committed to “Young Germany” ; invited as guest of honor by Johann Georg August Wirth; Participants in the meeting the previous day; the Metternich critical magazine Die Wage was banned |

| Main actors: |

|

Philipp Jakob Siebenpfeiffer : editor of the journals Rheinbayern and Der Bote aus Westen (later: Westbote ); Co-founder of the German Press and Fatherland Association on the “1. School party "; Initiator, author of the invitation to the Hambach Festival; Keynote speaker; Participants of the meeting in the Schoppmanns house |

|

Johann Georg August Wirth : editor of the magazine Deutsche Tribüne ; Co-founder of the German Press and Fatherland Association on the “1. School party "; Keynote speaker; Participants of the meeting in Schoppmann's house; Editor of the festival magazine |

| German Press and Fatherland Association: |

|

Friedrich Schüler : Bavarian Chamber Member; Co-founder of the German Press and Fatherland Association on the “1. School party "; Chairman of the board of the German Press and Fatherland Association; Speaker; Participants of the meeting in the Schoppmanns house |

|

Joseph Savoye : Chairman of the Board of the German Press and Fatherland Association; Speaker; Participants of the meeting in the Schoppmanns house |

| Ferdinand Geib : Chairman of the board of the German Press and Fatherland Association |

|

Daniel Friedrich Ludwig Pistor : author of articles for magazines; Secretary of the German Press and Fatherland Association; Speaker; Participants of the meeting in Schoppmann's house; later in the union of the outlaws |

|

Paul Camille von Denis : Member of the German Press and Fatherland Association; its main financier |

| Contemporary presentation of the Hambach Festival: |

|

Erhard Joseph Brenzinger : was a participant in the Hambach Festival together with his friends Bassermann , Mathy and von Soiron ; made the much varied etching of the Hambach Festival |

| Speakers and other important people who have pictures: |

|

Ernst Ludwig Große : Editor of the Bayerische Blätter and the Bavarian Chronicle ; authored pamphlets and essays critical of the government; Member of the German Press and Fatherland Association; Speaker |

|

Harro Harring : “professional revolutionary” and writer; involved in the meeting the day before |

|

Jacob Venedey : Employee at the Mannheim magazine Wächter am Rhein ; involved in the meeting the day before |

|

Karl Heinrich Brüggemann : Employee at Siebenpfeiffers magazine, formerly editor of Die Zeit ; Member of the German Press and Fatherland Association; Leader of a delegation of around 200 Heidelberg students; Speaker; Participants of the meeting in the Schoppmanns house |

|

Friedrich Deidesheimer : businessman and winery owner; Co-signer of the invitation to the Hambach Festival; Co-organizer; Speaker |

|

Johann Philipp Becker : brush maker and “professional” revolutionary; Founder of the Frankenthal branch committee of the German Press and Fatherland Association; Speaker |

|

Fritz Reuter : writer and publicist; Speaker |

|

Rudolf Lohbauer : editor of the Hochwächter ; Speaker |

|

Gustav Körner : lawyer and bookseller; later governor of Illinois . Member of the German Press and Fatherland Association; Participant in the Frankfurt delegation, which handed Wirth a sword for his services to freedom of the press |

|

Georg Friedrich Kolb : Publicist and publisher of the Neue Speyerer Zeitung ; Member of the German Press and Fatherland Association; as a reporter for the Metternich-critical NSZ at the Hambach Festival |

|

Johann Philipp Abresch : businessman; carried the flag "Germany's rebirth" |

Idea for the party and organization in advance

The authorities blocked the opposition press. The main actors of the Hambach Festival, Philipp Jakob Siebenpfeiffer and Johann Georg August Wirth, were no less affected. State authorities observed Wirth's newspaper Deutsche Tribüne from the first edition. Siebenpfeiffer's newspaper Westbote also harassed the authorities. At the beginning of 1832, the assigned mayor sealed Wirth's printing press because he was still producing his newspaper without permission. The same thing happened to Siebenpfeiffer.

The friends around Wirth, to which the Bavarian member of the Second Chamber Friedrich Schüler belonged, discussed the realization of the freedom of the press. In the July 12, 1831 edition, Wirth proposed an association to promote the free press. In order to honor the efforts of MPs, citizens held festivals during this period - meetings were forbidden by the authorities. One of these celebrations was held by the citizens of the Rhine- Bavarian region in Zweibrücken -Bubenhausen as a banquet on January 29, 1832 for Friedrich Schüler. The participants of this " First Student Festival " saw themselves as patriots . Their demand was that every lawfulness had to be derived from popular sovereignty and could no longer be justified by divine legitimation of kingship. If this change were to take place, it would be the foundation for “Germany's rebirth”. As a continuation of the idea, those present founded the German Fatherland Association to support the free press (German Press and Fatherland Association - PVV). In Wirth's newspaper of the Deutsche Tribüne the article “ Germany's obligations ” appeared on February 3, 1832 , calling for support for the association. The newspaper itself acted as an association organ and reported on current developments. The provisional chairmanship took place on February 21st, together with the two lawyers Joseph Savoye and Ferdinand Geib .

Prince von Metternich urged the German Confederation in March to put an end to the hustle and bustle. The Bavarian government acted accordingly and issued a general association ban on March 1, which also included the press and fatherland association. In addition, they also banned the German tribune . A day later the press commission of the German Confederation also issued a ban on the newspapers Siebenpfeiffers and Wirths. Even Wirth's arrest on the 16th of the month did not break the spirit of the opposition. Rather, other publications filled the gap created, such as the journal Bürgerfreund by Johann Heinrich Hochdörfer . The appellate court (court of appeal) in Zweibrücken acquitted Wirth on April 14th. The verdict led to public sympathy and affirmed that journalists were allowed to defend themselves against the censorship. The acquittal of Wirth and the injustice of the prohibition of associations that it implied brought great popularity to the Press and Patriotic Association.

Siebenpfeiffer suggested organizing a "German National Festival" in what was then "Neustadt an der Haardt". The event was to take place on and near the castle ruins in "May full of prayer" in "Hambach an der Haardt". Siebenpfeiffer wrote the invitation for it. Schoolchildren, Savoye, Geib, the local association of the German Press and Fatherland Association and other people around the town of Neustadt organized the festival. On April 20, 1832, the invitation to the “National Festival of Germans” appeared in the press. The Bavarian government tried to prevent the festival through its representative Andrian-Werburg . He forbade it and on May 8th issued an ordinance that limited access to Neustadt, Winzingen and Hambach, granted the police special rights to close inns, prohibited gatherings of more than five people and the making of speeches in public places. The Neustadt City Council protested, and surrounding towns in the region joined in. The board of directors of the German Press and Fatherland Association also sued. The government had to withdraw the regulation. But in order not to expose Andrian-Werburg, she let the ban on the festival exist. The pros and cons increased interest in the festival and mobilized the public.

Days before and train to the castle

Most of the festival participants arrived on May 26th, with the popular journalist Ludwig Börne , invited by Wirth as guest of honor, arriving on May 24th. Dr. Hepp and Philipp Christmann received him. They showed him the ordinance of the Bavarian authorities, which forbade foreigners apart from Rhine Bavaria to participate. The people of Neustadt sold black, red and gold cockades and song texts for the upcoming train to the castle, for example in the bookstore of Christmann, the later “Scheffelhaus”. In addition to the “German” cockades, they also offered French blue-white-red. The latter created discontent among some such as Wirth. The Press and Fatherland Association Committee disapproved of the sale and insisted on the Palatinate character of the festival.

In the evening journalists and liberals gathered in the Neustadt shooting range . Among them were the prominent German oppositionists Börne, Harro Harring and Jakob Venedey , Lucien Rey, the member of the Strasbourg society La Sociétè des amis du peuple and the representatives of the Polish National Committee from Paris. At this meeting "the great interests of the common fatherland" were discussed. According to one participant, there was a formal vote on the question raised by the student Heinrich Kähler from Itzehoe, "whether you want to chat again or whether you have not come to strike [sic]", in which those present opposed the strike decided. The festivities began that evening. The festival begins with the ringing of bells, the firing of guns and the lighting of bonfires.

On May 27th at 8 a.m., again accompanied by the ringing of bells and gunshots, the train to the castle formed on the market square in Neustadt. This was arranged in the following order: a civil guard with music, women and maidens, among whom an ensign carried the Polish flag, another civil guard, the festival files and below the black-red-gold flag of Abresch with the inscription "Germany's rebirth", followed from the district administrators of Rhine Bavaria, other festival files, delegations from other small states and the festival visitors. Another section of the civil guard completed the pageant. The participants moved from Neustadt to the Hambach Castle ruins, which are four kilometers from the city center and 200 meters higher. Several songs were sung along the way. The winegrowers of the Palatinate drew attention to their economic situation with their flag “The winegrowers must mourn”.

The 20,000 to 30,000 participants gathered around 11 a.m. on the castle ruins. The participants came from all walks of life and from numerous nations - from students to parliamentarians , from French to Poles to English and from 15 small German states . After arriving at the site, the festival committee hoisted the Polish flag on a raised point of the castle ruins and the German flag on the highest battlements with the inscription "Germany's rebirth". Many women also took part, because Siebenpfeiffer's invitation to invite said: "German women and virgins, whose political disregard in the European order is a mistake and a blemish, adorn and enliven the assembly with your presence!"

First day of celebration at the castle

At the opening, “Dr. Hepp ”gave the first speech on the main stand on behalf of the festival stewards. The second speaker was Philipp Jakob Siebenpfeiffer , who made the following statements, among other things:

"... We dedicate our lives to science and art, we measure the stars, test the moon and sun, we depict God and man, hell and heaven in poetic images, we rummage through the world of bodies and spirits: but the impulses of love for the fatherland are unknown to us, the investigation of what is in need of the fatherland is high treason, even the faint wish to strive for a fatherland again, a free human home, is a crime. We help Greece free from the Turkish yoke, we drink to Poland's resurrection, we are angry when the despotism of the kings paralyzes the impetus of the peoples in Spain, in Italy, in France, we fearfully look at the reform bill of England, we praise the strength and the power Wisdom of the sultan, who deals with the rebirth of his peoples, we envy the North American for his happy lot, which he courageously created for himself: but we bow our necks servile under the yoke of our own urges; when despotism sets out to oppress others, we still offer our arms and our possessions; our own reform bill disappears from our powerless hands ... "

Siebenpfeiffer concluded his opening speech with the words: “Long live the free, the united Germany! Long live the Poles, the German allies! Long live the Franks , the German Brothers, who respect our nationality and our independence! Long live every people who break their chains and swear the covenant of freedom with us! Fatherland - national sovereignty - high league of nations! ”Siebenpfeiffer was followed by Johann Georg August Wirth , whose speech ended with the following words:

“That is why, German patriots, let us choose those men who are called by spirit, ardor and character to begin and lead the great work of German reform; we will find them easily and then also move them through our requests to make the holy covenant immediately and to open up their meaningful effectiveness immediately. May this beautiful covenant guide the fate of our people; May he begin the struggle for our highest goods under the umbrella of the law; he may awaken our people in order to generate the strength for Germany's rebirth from within, without external interference; He may also come to an understanding at the same time with the pure patriots of the neighboring countries, and if he has been given guarantees for the integrity of our area, then he may at least seek fraternal union with the patriots of all nations, who stand for freedom, popular sovereignty and national happiness are determined to commit life. High! The united Free States of Germany live three times as high! High! three times high to confederate republican Europe! [sic] "

In recognition of his struggle for freedom of the press, Johann Friedrich Funck from the Frankfurt delegation presented Wirth with a sword with "Dem Wirth / German in Frankfurt" and the slightly changed fraternity motto "Fatherland - Honor - Freedom" engraved on the blade. Like Siebenpfeiffer, Wirth called for the end of absolutism. In addition, the two called for national unity. Siebenpfeiffer called on the Germans to overcome small states through brotherhood and scoffed at the constitutions of those states that were only given to the people to play with as "little constitutions". For Wirth, unity was the means to the freedom of the European peoples, but he warned the French against making claims on the left Rhineland. The main speaker was followed by the representative of the French delegation, Lucien Rey. He criticized Wirth's speech because he emphasized the solidarity of the French to the previous speaker.

Meanwhile it was noon. Since the association law forbade gatherings with more than 20 people, the organizers staged the festival as a banquet in a "closed society". About 1400 people were present for dinner. Dr. Hepp gave the dinner speech, in which he once again dealt with the officials who tried to prevent the festival and who had disparaged those present as a "party of evil-minded creeping in the dark".

The speaker was Johann Heinrich Hochdörfer , who expressed his radical views with these words, among other things:

“Poor people! You stand in amazement and can't believe how you can get through the work sweat of a whole people. But just look at your vaunted constitutional charter and it will solve the gruesome riddle itself. [...] Here, mocked people, you have been told: Create, honestly feed on your hands' work - that, that is [...] bourgeois, but not aristocratic, that defiles, rather robs the nobility. Noble is only, says your constitution, comfortable, rich, elegant, lavish living - from foreign sweat. "

Hochdörfer's speech and others were not printed in the Wirths festival magazine because they were considered too 'seditious'. The Austrian observer noted in 1838 that Friedrich Wilhelm Cornelius' speech was so "dripping with blood that it could not have been printed". 21 speakers are said to have had their say, and the number of about 33 speakers is given for the entire festival. Most of the festival participants were unable to follow the official festival program on the spacious grounds. In order to convey their thoughts to those present, the speakers repeated their statements in other places on the premises. The main demands were national unity , freedom, in particular freedom of assembly , freedom of the press , freedom of expression , civil rights , the reorganization of Europe on the basis of equal peoples, popular sovereignty and religious tolerance .

Second feast day and meeting in Neustadt

On May 28, 1832, senior citizens and students met again in the Neustadt shooting house. About 500 to 600 participants were present at the event, which had been announced the previous evening. The further procedure was available for discussion. In a letter from the same day, the publicist Börne described the turbulent atmosphere in the localities: “Last night the Heidelberg students brought me a vivat with a torchlight procession in front of my apartment, led by the herald . Even before, everything followed me on the streets with shouts: long live Börne, long live the German Börne! ”Siebenpfeiffer asked those present to come together to make decisions about the reforms that appeared necessary. Those present should choose men they trust. These in turn face the Bundestag as a provisional government (as a national convention or as a national representative of the people ).

Subsequently, a meeting of the elected representatives took place that same morning in the apartment of the Schoppmann state estate. Student led the meeting. Those present agreed to organize similar celebrations in other regions of the federal government. In addition, the Press and Fatherland Association should have three press organs. Siebenpfeiffer and Wirth took over the editing of the festival description. Some of those gathered considered a violent overthrow. Others spoke out against it. Several speakers equated armed force with usurpation , which, according to their opinion, was a demand against law and popular sovereignty. The decision was therefore negative. At the same time there was a break between Siebenpfeiffer, Wirth and the Central Committee over the commitment of the German Press and Fatherland Association. Wirth pleaded for the further development of opposition structures by transforming the association into a powerful political organization. However, Schüler blocked all further requests by questioning the competence of those present. In this assembly, at which representatives of the “German Gaue ” were elected, a permanent national convention was almost formed. The final vote on the question of whether a constitution would by itself have the competence to start a revolution in the name of all of Germany, however, let the efforts fail because no agreement was reached.

The following days until the end of the festival

In the following days, many thousands are said to have come to Hambach Castle every day, even if the majority left on May 28th. The celebrations ended on June 1st with the collection of the Polish flag and the flag of “Germany's Rebirth”. The two speakers Franz Grzymala and Zatwarnicki from the Polish delegation gave speeches on the occasion. After this, fixed folders spoke.

Many citizens accompanied the civil guard with the flags on the way from the castle back to Neustadt. The deputy Schopman as senior (elder) of the festival stewards kept the flags handed over to him after the decision. Wirth also noted the following in the festival description:

At the Hambach Festival, a large number of visitors carried black, red and gold tricolors with them and / or wore cockades of the same color, which were supposed to symbolize the striving for national unity. The colors had spread in connection with the fraternity movement as a symbol of the bourgeois-liberal national movement and come from the song " We had built a stately house ", which was created on the occasion of the dissolution of the Jenenser original fraternity in 1819. Contemporary wood and steel engravings show that the color sequence was reversed at the time; it was read from bottom to top.

In contrast to this, Johann Philipp Abresch from Neustadt carried the flag in the department of pageant files, the color sequence of which was black-red-gold, like today, from top to bottom and on which "Germany's rebirth" was written. This original flag from 1832 is kept in the museum of Hambach Castle. The Weimar Republic , the Federal Republic of Germany and also the GDR invoked the color sequence read from above.

consequences

Gustav Körner suspected that

"The wrath of kings and princes would strike many of us."

Immediately after the Hambach Festival, emissaries (emissaries) delivered messages to the members of the Press and Fatherland Association. Von Rauschenplatt had traveled to Heidelberg before the Wilhelmsbad Festival to deliver the news that Schüler, Savoye and Geib had been "reconciled" with Siebenpfeiffer and Wirth. The association encourages people to organize celebrations. Furthermore, von Rauschenplatt inquired about the means for a revolution to break out. Even before the festival, some were in the mood that this letter of February 6, 1832, for example, reproduces: “The effect that the passage of the Poles has on the German minds is enormous, it will certainly not disappear again anytime soon. We have until the end of June to maintain and increase it, but then something decisive must happen under every condition. If the company remains without strong external support until then, Thuringia is the best place on which the fire can be kindled. ”However, the revolution did not materialize. The poet and journalist Heinrich Heine later criticized this apparent inactivity : “During the days of the Hambach Festival, the general upheaval in Germany could have been attempted with some prospect of good success. Those Hambach days were the last appointment that the goddess of freedom granted us ... "

The Hambach Festival generated a response in the German press. Extensive articles and reports appeared in newspapers in the neighboring small states. The returning festival participants set up trees of freedom in their cities to show their solidarity. In contrast to the peaceful course of the Hambach Festival, after May 27, the pent-up discontent about the political and economic circumstances in many communities was released. This led to minor local uprisings. This happened, for example, in Worms and Frankenthal . The main focus of the wave of protests against the government was in St. Wendel . Only after 1,000 Prussian soldiers marched in and a state of emergency was imposed did calm return there. There were consequences in government too; for example, the new general commissioner Carl Freiherr von Stengel followed the recalled Andrian-Werburg .

It was remarkable that a number of moderate liberals stayed away from the Hambach Festival. They included the editors of the Staats-Lexikons Karl von Rotteck and Carl Theodor Welcker , the Marburg constitutional lawyer Sylvester Jordan , the landowner Johann Adam von Itzstein and the Göttingen historian Friedrich Christoph Dahlmann . With the exception of Dahlmann's, these were nevertheless depicted on the Hambach cloth from 1832.

For conservative representatives, the festival was an "exception". Metternich spoke of the “Hambach scandal” and the Austrian envoy in Stuttgart even saw “the grinning features of anarchy and civil war”. The direct consequence for the organizers and speakers at the festival was prosecution . The extraordinary Assisengericht (jury court), which met in Landau and met from July 29 to August 16, 1833, brought charges against 13 accused. The proceedings ended with the acquittal of the main defendants, but then new trials started in Zweibrücken and Frankenthal on account of alleged libelous offenses. The negotiating breeding police courts then produced the convictions expected by the government. Some fled to Switzerland, such as Siebenpfeiffer and Wirth. Student settled down to France. From exile they kept in contact with fellow campaigners in Germany through their connections to members of the German Press and Fatherland Association, Young Germany in Switzerland, or the League of Outlaws in France.

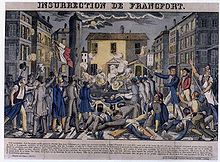

Some of the participants in the Hambach Festival sounded like they were in favor of the violent coup. The amateurish Frankfurt Wachensturm of 1833 confirmed this, although it is not directly related to the Hambach Festival, according to sources, but rather there were only personal overlaps. The courts convicted several participants in the guard tower, such as the Hambach speakers Karl Heinrich Brüggemann , before the king to death highest of all pardoned to years of stringent penal servitude. Other parties wanted in wanted letters, such as Gustav Körner, escaped the proceedings through emigration. His later life remained political and he rose to lieutenant governor of Illinois in the new adopted home USA , which earned him the trust of Abraham Lincoln, who was supported in the election campaign . The so-called " thirties " like grains, who saw themselves forced into illegality, left the territory of the German Confederation.

In general, the German Confederation reacted in the years after 1832 with increased repression . He had people from the bourgeoisie who were suspected of sympathizing with revolutionary ideas arrested, restricted freedom of assembly and the freedom of the press, and monitored universities. The reactionary measures, which meant a drastic tightening of the Karlsbad resolutions of 1819, brought the republican movement to a standstill for the time being. On July 5, 1832, the Federal Assembly passed ten articles "to maintain the legal order and calm in the German Confederation", which supplemented the six articles of June 28, 1832 and are a reaction to the Hambach Festival. Not least because of the festival, the guard tower and the related Franckh-Koseritz conspiracy , the federal government created the federal central authority based in Frankfurt on June 30, 1833. This inquisition body investigated more than 2,000 suspects until it was dissolved in 1842 and registered them in the "Black Book". Many withdrew from political life, the so-called Biedermeier lifestyle intensified. Denunciations and informers contributed significantly to this. Nevertheless, the bourgeoisie expressed their striving for a unified Germany, for liberality and popular rule by purchasing and using appropriate handicrafts. Among other things, crockery depicting the Hambach Castle was very popular. The government confiscated these souvenirs as they were supposed to bear witness to revolutionary sentiments.

During the March Revolution of 1848/49 the republican movement revived and was initially able to partially implement its goals. Schoolchildren , Wirth , Venedey and other participants in the Hambach Festival returned from exile. The population elected some of them to the Frankfurt National Assembly . Its approximately 585 members came from all German-speaking areas including Austria and mostly had professions such as senior civil servants, judges or professors, which is why there was also talk of the “professors' parliament”. The elected drew up the Paulskirche constitution .

The suppression of the March Revolution led to another wave of opposition emigrants, particularly to the United States of America . The so-called Forty-Eighters continued to support their ideals there. You are committed to the implementation of the Confederate Republic , civil rights and the abolition of slavery . Because of their military experience from the revolution, Germans were also represented in high officer ranks in the Civil War and provided entire regiments.

Only after the restoration phase and the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71 came to a " small German " unification in the German Confederation - albeit brought about from above . With the exclusion of Austria and with reference to the “Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation”, the Prussian Prime Minister and later Chancellor Otto von Bismarck initiated the German Empire under Kaiser Wilhelm I.

Memory of the feast

The Hambach cloth reminded of 16 men who were closely connected to the Hambach Festival.

Reception and memory history in representations of German school books

The Hambach Festival was and is continuously present in school education through its imprint in German school books. This makes it an essential part of the collective memory of many generations. However, the representations and interpretations of the Hambach Festival are very different depending on the historical context in German textbooks in the flow of time.

The German Imperium

The textbook on the Hambach Festival was written by Friedrich Nösselt and is an excerpt from the book World History for Daughter Schools and for Private Use by Adolescent Girls and was published in Stuttgart in 1880.

In school books at the time of the German Empire, the Hambach Festival was interpreted in such a way that the people are represented as a whole and individual people who have participated are not named, such as B. Siebenpfeiffer . In the empire the people had few rights of participation. Therefore this text was written from the perspective of the government, used as a textbook; and it intends that the government tried to convey to the people only the values of the empire or the constitutional monarchy, but not the liberal values that were represented at the Hambach Festival. Since the text does not explicitly mention Siebenpfeiffer's speech, the learners are not informed exactly why the fraternities and journalists celebrated the Hambach Festival, initially announced as the “Constitution Festival”. This ensures that the students who read this text did not get to know the reasons and causes for the celebration of the Hambach Festival. The author gives imprecise mention of which parts of society took part. Other groups of participants, such as B. According to the text of the textbook, the participating students were manipulated by followers of Siebenpfeiffer.

The demand for the unity of the Hambach Festival has already been met by the German Empire. Other events are only mentioned vaguely, so that the people cannot understand that democracy, freedom and equality were also demanded at the Hambach Festival, which did not exist in the German Empire in the sense of liberal ideas.

Weimar Republic

In the textbook for the Hambach Festival published in 1922 in From the History of the Nations , the Hambach Festival is presented as a glorious and important event. The text mainly mentions the speakers, the foreign allies and the participants of the festival, especially women, journalists, students and writers. It is invariably described as a positive event. It is also played as a retelling, which does not describe the event neutrally.

The authors evaluate some speeches, such as that of Johann Georg August Wirth. In addition to evaluating some of the speeches, they present the claim to Alsace-Lorraine, mentioned by Karl Brüggemann, as problematic. This is a provocative claim, since both Germany and France are claiming the country for themselves.

They generally call the festival a great success in which the basic values were demanded on which the first parliamentary democracy in Germany was based.

time of the nationalsocialism

The history book for German youth, which appeared in Leipzig in 1940, deals, among other things, with the National Liberal Movement of the Hambach Festival from a National Socialist perspective. The national liberal movement at the time of the Hambach Festival in 1832 is limited to the national idea and liberalism is criticized. According to the national idea, there would be an ideal man who “devotes all his energy to the state”, who works for a united people and, contrary to this, Judaism is represented, which is the embodiment of liberalism. Liberalism wants to disempower the state and therefore represents a danger. Judaism is assumed to be instrumentalizing the movement in order to gain power themselves. France is also seen as a predatory enemy, whose defeat was celebrated at the Wartburg Festival . In contrast to the Wartburg Festival, which was shaped purely by national ideas, the Hambach Festival also expressed liberal ideas. This stands above the national idea and should therefore be interpreted as a danger.

GDR

In the textbook textbook for the history lesson of a collective of authors from the Volk und Wissen Verlag from 1952 in East Berlin, the ideas of the Hambach Festival were interpreted as progressive and positive. Above all, workers are represented as groups of people who played an important role in the GDR. Only German speakers are quoted, such as Dr. Wirth or Siebenpfeiffer. In addition, words such as “passionate” or “cheering” are used, which also illustrates the positive attitude.

The longing for German unity becomes clear through the quote “the day will come”, since Germany was divided into two blocks at the time of the GDR. The constitutional movement and liberalism were supported as the people were marked by the previous dictatorship .

The Hambach Festival was seen as a model for the subsequent reunification efforts during the GDR era. That is why one recognizes in the source again and again a positive attitude towards the demands of the Hambach Festival.

Anniversaries

In the run-up to the 50th anniversary in 1882, quarrels arose because a dispute broke out between social democrats, liberals and monarchists over the classification of the festival. The Neustadt District Office then banned all events in concern for public order. The raising of a red flag on Hambach Castle by the Social Democrat Franz Josef Ehrhart , which was prevented by the gendarmerie , met with a public response .

The centenary celebrations in 1932 were organized by the Neustadt Tourist Office and the Palatinate Press Working Group. Protestants from the Palatinate National Socialists disrupted the event. They defamed the guest of honor at the Hambach Festival, Carl Ludwig Börne, with anti-Semitic slogans. The speech on the day of remembrance was given by the later Federal President Theodor Heuss , as the originally planned Karl Alexander von Müller was ill.

The young Federal Republic of Germany used the 125th anniversary in 1957 to emphasize democratic principles. The state government of Rhineland-Palatinate organized a memorial hour on May 26, 1957, during which the politicians August Wolters , Peter Altmeier , Max Becker and Carlo Schmid spoke. In 1969, the latter campaigned for the palace to be converted into a “monument to German democracy”.

Before the celebrations for the 150th anniversary in 1982, the Rhineland-Palatinate state government excluded all other political forces from the planning. At the instigation of Prime Minister Bernhard Vogel (CDU), the castle ruins were to be turned into a "documentation center for the history of the Hambach Festival" at a cost of millions. For this purpose, the castle was restored and expanded, and the outside area on the Schlossberg was prepared.

The Federal Republic of Germany brought on 5 May in 1982 by the German Federal Post Office a special stamp 150 years Hambach 50 penny out ( Michel number 1130). This corresponded to the postage for a postcard at that time .

The start of the celebrations for the 175th anniversary of the festival included the Hambach Castle Marathon for the first time on April 1, 2007 , which led from Neustadt up to the castle and via various wine villages back to Neustadt with 2200 participants. The main speaker at the ceremony on May 27, 2007 was the former Federal President Richard von Weizsäcker . Already on May 11, 2007, the poem by Albert H. Keil Nuffuff's Castle ( Palatine for “up to the castle”) was awarded a prize at the dialect competition Dannstadter Höhe . On June 19, 2007, more than 11,000 students from the Palatinate region took the traditional route from Neustadt or Kirrweiler up to the castle and celebrated the Hambach Festival of Youth, organized by the Palatinate District Association .

In his speech on the occasion of the 180th anniversary in 2012, the President of the European Parliament , Martin Schulz (SPD), emphasized the importance of the Hambach Festival for freedom of speech and the press and against censorship. He described the participants at the time as dreamers of a “confederate Europe”, a “Europe of the peoples”, and with the demand “Freedom, Unity and Europe” referred to the wording of the banners. These were "already" worn at the pageant in 1832.

Societies, foundations and award ceremonies

In 1986 the "Hambach Society for Historical Research and Political Education e. V. ”with the aim of promoting the memory of the Hambach Festival. It publishes yearbooks and organizes lectures, panel discussions, exhibitions, artistic performances and excursions.

In addition to this, the Hambach Castle Foundation has been preserving the memory since 2002. Its task is to preserve and maintain the Hambach Castle as an “important site for the development of democracy in Germany and European cooperation”. The donors were the state of Rhineland-Palatinate , the district association of the Palatinate , the district of Bad Dürkheim , the city of Neustadt an der Weinstrasse and the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and Media of the German Bundestag .

In recognition of the achievements of people who were also participants in the Hambach Festival, various organizations donated three prizes:

- Since 1987, the Philipp-Jakob-Siebenpfeiffer-Stiftung has awarded the Siebenpfeiffer Prize to journalists who - regardless of their career or financial advantages - have achieved merit through publications in the press, radio and television.

- Since 1993, the Ludwig Börne Foundation has awarded the Ludwig Börne Prize annually in the Paulskirche in Frankfurt to German-speaking authors who have achieved outstanding results in the field of essays, criticism and reportage.

- Since 2009 the Academy for New Media in Kulmbach has been awarding the Johann-Georg-August-Wirth-Prize to people who have made a special contribution to the education and training of young journalists.

present

As a German symbol of freedom, the castle is a stop on the Straße der Demokratie , established in 2007 , which leads from Frankfurt to Lörrach . It is a museum and conference venue with around 200,000 visitors a year. Events and receptions from the state of Rhineland-Palatinate, the Bad Dürkheim district and the city of Neustadt an der Weinstrasse take place in the castle all year round.

In a permanent exhibition in the castle, flags, a printing press and contemporary documents can be viewed. One of the black, red and gold flags of the Hambach Festival hangs in the plenary hall of the Rhineland-Palatinate state parliament in the Deutschhaus in Mainz . Another hung in the large conference room of the Federal Constitutional Court in Karlsruhe ; it was preserved and replaced by a new flag.

In May 2018 and June 2019 events took place on site under the name Neues Hambacher Fest , which were supposed to tie in with the tradition of the Hambacher Festival of 1832. They were organized by Max Otte , the chairman of the board of trustees of the AfD- affiliated Desiderius Erasmus Foundation . The events are socially controversial.

swell

- Johann Georg August Wirth: The national festival of the Germans in Hambach . Philipp Christmann, Neustadt 1832 ( preview in Google book search).

- Ludwig Hoffmann (ed.): Complete negotiations before the king. Bayer. Appeal courts against Dr. Wirth, Siebenpfeifer, Stockdörfer… G. Ritter, Zweibrücken 1832 ( digitized version ).

- Franz Xaver Remling: The Maxburg near Hambach . Schwan and Götz'sche Hofbuchhandlung, Mannheim 1844, p. 130 ff. (§ 43) ( limited preview in the Google book search).

literature

Overarching

- Hans-Werner Hahn, Helmut Berding: Handbook of German History / Reforms, Restoration and Revolution 1806–1848 / 49 . tape 14 . Klett-Cotta, 2009, ISBN 978-3-608-60014-8 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society 1815–1845 / 49 . Fourth edition 2005. CH Beck'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung (Oscar Beck), Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-32262-X ( limited preview in the Google book search).

Representations

- Lutz Frisch: Germany's rebirth. Neustadt citizens and the Hambach Festival in 1832 . District group Neustadt in the Historical Association of the Palatinate, Neustadt an der Weinstr. 2012, ISBN 978-3-00-037610-8 .

- Joachim Kermann, Gerhard Nestler, Dieter Schiffmann (eds.): Freedom, Unity and Europe. The Hambach Festival of 1832 - causes, goals and effects . Pro Message publishing house, Ludwigshafen 2006, ISBN 3-934845-22-3 .

- Helmut Gembries: 175 years of the Hambach Festival . Ed .: Hambach Society for Historical Research and Political Education e. V. Hambach-Ges. for historical research and political education, Neustadt an der Weinstrasse 2006.

- Joachim Kermann: Harro Harring, the fraternities and the Hambach Festival. The fraternity motif in his drama “Der deutsche Mai” . In: Helmut Asmus (Ed.): Student fraternities and civil upheaval . For the 175th anniversary of the Wartburg Festival. Akademieverlag, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-05-001889-5 , p. 197-217 .

- Cornelia Foerster: The Press and Fatherland Association of 1832/33. Social structure and organizational forms of the bourgeois movement during the Hambach Festival (= Trier historical research . Volume 3 ). Trier 1982.

- Hedwig Brüchert, Hambach Castle Foundation: Up, up to the castle! The Hambach Festival 1832. Book accompanying the exhibition in Hambach Castle . Neustadt an der Weinstrasse 2008, ISBN 978-3-00-026772-7 .

- Ministry of Culture Rhineland-Palatinate (Ed.): 1832–1982. Hambach Festival. Freedom and Unity, Germany and Europe . Neustadt an der Weinstrasse 1982, ISBN 3-87524-034-0 (Catalog for the exhibition by the State of Rhineland-Palatinate on the 150th anniversary of the Hambach Festival. Hambach Castle, May 18 to September 19, 1982).

- Adam Sahrmann : Contributions to the history of the Hambach Festival in 1832 . Landau in der Pfalz 1930 (new edition Vaduz 1978).

- Veit Valentin : The Hambach National Festival . Berlin 1932 (new edition Vaduz 1977).

Web links

- Literature on the Hambach Festival in the catalog of the German National Library

- Wilhelm Kreutz: Hambach 1832 - German freedom festival and harbinger of the European springtime. (PDF; 783 kB; approx. 100 undefined pages) State Center for Political Education Rhineland-Palatinate, Mainz 2007

- Portal of the permanent exhibition (since 2007) at Hambach Castle

- Exhibition for the Hambach Festival . hambacher-schloss.de

- Hambach Festival. Downloads (PDF). Institute for Historical Regional Studies at the University of Mainz, 2007

- The Hambach Festival. The cradle of German democracy. (No longer available online.) In: deutsche-heimat.de. Stadt Neustadt, 1998, archived from the original on May 3, 2001 .

- Johann August Wirth at the Hambach Festival (May 1832). Speech by Johann August Wirth at the Hambach Festival

Remarks

- ↑ See resolutions at the Wartburg Festival

- ↑ Example of an unjust judgment: "Karl Stahr - 5 years in prison as a former fraternity member because of his collection of Aristotelian works on Politien (needed for his philosophical studies) and the possession of a lady's hat ribbon with forbidden colors that was wrapped around a packet of poems" in Max von Boehn, Biedermeier - Germany from 1815–1847 , Paderborn, 2012, p. 55 f

- ↑ From 1936 to 1945 and since 1950 Neustadt an der Weinstrasse

- ↑ Today, like Neustadt, Hambach an der Weinstrasse, an independent village until 1969

- ↑ In particular: Ph. Abresch (Economics); S. Baader (Economist); S. Baader (wine merchant); Blaufus (businessman); Ph. Christmann (bookseller); F. Deidesheimer (businessman); G. Frey (economist); F. Gies (Economist); Göttheim (businessman); Lh. Heckel (Economist); Dr. Hepp (doctor); G. Helfferich (businessman); C. Hornig (wine merchant); I. Hornig (Economist); Käscler (businessman); F. Klein (Gerber); G. Klein (landowner); H. Klein (Economist); K. Klein (Economics); I. I. Lederle (businessman); Lembert (notary); Ch. Mattil (economist); W. Michel (Economist); Müller (notary); I. Racy (businessman); Sneeze (tailor); Schimpf (mayor); I. Schopmann (country estate); I. Umbstätter (Oekonom); F. Brod (businessman); Walther (Kaufmann) in Johann Georg August Wirth: The national festival of the Germans in Hambach. Neustadt 1832, p. 5 ff.

- Jump up to the protest Neustadts - Zweibrücken , Frankenthal , Kaiserslautern , Landau and Speyer in Johann Georg August Wirth: The National Festival of the Germans in Hambach. Neustadt 1832, p. 7 f.

- ^ 9 a.m. in Wilhelm Kreutz, Hambach 1832 - German Freedom Festival and Harbinger of the European Spring of Nations, Mainz, 2007, p. 22.

- ↑ Songs: “Up, Patriots! to the castle, to the castle! ”by Siebenpfeiffer; Song for the May Festival by Christian Scharpff; What is the German Fatherland from Ernst Moritz Arndt ; Songs by Theodor Körner ; Winzerlied and others see Wirth & in Wilhelm Kreutz's festival magazine : Hambach 1832. German freedom festival and harbinger of the European springtime. Mainz 2007, p. 23 f.

-

↑ Participants:

20,000 participants as stated in Die Maxburg bei Hambach , p. 134 of the per F # 243 p. 130 f. " Sine ira et studio " written work Die Maxburg bei Hambach , Schwan and Götz'sche Hofbuchhandlung, 1844, by pastor and school inspector Franz Xaver Remling

30,000 participants as information from the festival committee in Wirth's festival magazine

25,000 to 30,000 participants as information in reports from the investigative commission of the Deutsche Bunds

60,000 participants as information at Siebenpfeiffer for testimony before the investigative commission of the German Bund - ^ "Francs" German for "French"

- ↑ See those named as speakers in the list of participants at the Hambach Festival : Dr. Hepp , Siebenpfeiffer , Wirth , Hallauer , Fitz , Barth , Brüggemann , Deidesheimer , Becker , Frey , Hochdörfer , Lohbauer , Stromeyer , Widmann , Schoppmann , Große , Scharpff , Cornelius , Schüler , Savoye , Reuter , Funck , Pistor , Franz Grzymala (Polish Delegation), Oranski (Polish delegation), Zatwarnicki (Polish delegation), Rey (“La Sociétè des amis du peuple”), Eduard Müller and Michael Müller

- ↑ Herald as leading messenger ; "Vivat" as a student tradition Hochruf see " vivat, crescat, floreat " - "live, bloom and prosper"

- ↑ Present were: Siebenpfeiffer , Wirth , Schüler , Savoye , Brüggemann , Georg Strecker, Hütlin (Mayor of Konstanz ), Delisle (City Council of Konstanz), Cornelius, Funck , von Rauschenplatt , Stromeyer , Hallauer , Meyer, Huda, Berchelmann, Venedey and more Coincidence Benjamin Ferdinand von Schachtmeyer (Rittmeister ret.) In Benjamin Krebs: Presentation of the main results from the investigations carried out in Germany because of the revolutionary plot of recent times. Frankfurt am Main, 1838, p. 26 books.google.de & in Dr. Anton Bauer: Criminal Law Cases. Göttingen, 1837, p. 286.

- ↑ The Mannheim Guard on the Rhine were intended as the press organs ; the Volkstribüne and a new newspaper, The Rebirth of the Fatherland , which was to emerge from Siebenpfeiffer's Westbote and Wirth's German Tribune . see in Wilhelm Kreutz, Hambach 1832. German freedom festival and harbinger of the European springtime. Mainz, 2007, p. 32

- ↑ Von Rauschenplatt , for example, spoke out in favor of an immediate formation of the national convention and the determination of a day on which the flag of rebellion should be raised and thrown out. in Benjamin Krebs: Presentation of the main results from the investigations carried out in Germany because of the revolutionary plots of recent times. Frankfurt am Main 1838, p. 26.

- ↑ Funck said at the meeting: "Either they wanted to go ahead and then they had to stay, or they did not want to go ahead, what he thought was appropriate, then one had to go." Later he published in his magazine Eulenspiegel : "One must definitely say that that one must oppose mere judgments of power with solemn custody, but that one cannot counter the open violence, which dares to overturn law and justice, other than with arms. ”In Benjamin Krebs: Presentation of the main results from the revolutionary plot recent investigations conducted in Germany. Frankfurt am Main 1838, p. 26.

- ^ Panner as a banner in Albert Schiffner: General German Subject Dictionary , Volume 11, Meissen, 1836 Banner = Panner

- ↑ Cities with trees of freedom : Neustadt, Frankenthal, Rockenhausen , Grünstadt , Freinsheim , Oggersheim , Dürkheim , Alsenborn , Steinwend , Kirrweiler , Mörzheim , Wollmesheim , Eschbach , Arzheim , Annweiler , Münchweiler , Leimen , Contwig , Blieskastel and Lautzkirchen in the Rhineland-Palatinate Ministry of Culture: 1832-1982. Hambach Festival. Freedom and Unity, Germany and Europe. Neustadt an der Weinstrasse 1982 (catalog for the exhibition by the state of Rhineland-Palatinate on the 150th anniversary of the Hambach Festival. Hambach Castle, May 18 to September 19, 1982). Lostermann, Vittorio, 1975, p. 168.

- ↑ Cf. “The Federal Central Authority / the President of the Federal Central Authority (signed) by the federal resolution of June 20, 1833, Frhr. v. Wagemann ", in: Presentation of the main results from the investigations carried out in Germany because of the revolutionary plots of recent times , 1838, p. 75 ( limited preview in the Google book search)

Original sources

- ↑ Heinrich Remigius Sauerländer: The sincere and well-mannered Swiss messenger . tape 29 . Heinrich Remigius Sauerländer, Aarau 1832, p. 91 ( in Der Bayrische Volksfreund ).

- ^ A b Johann Georg August Wirth: The national festival of the Germans in Hambach . Neustadt 1832, p. 4 ( Preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ Johann Georg August Wirth: The national festival of the Germans in Hambach . Neustadt 1832, p. 5 ff . ( Preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ A b Johann Georg August Wirth: The national festival of the Germans in Hambach . Neustadt 1832, p. 7th f . ( Preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Benjamin Krebs: Presentation of the main results from the investigations carried out in Germany because of the revolutionary plots of recent times . Federal President's Printing Office, Frankfurt am Main 1838, p. 23 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ A b Johann Georg August Wirth: The national festival of the Germans in Hambach . Neustadt 1832, p. 11 f . ( Preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Benjamin Krebs: Presentation of the main results from the investigations carried out in Germany because of the revolutionary plots of recent times . Federal President's Printing Office, Frankfurt am Main 1838, p. 23 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Johann Georg August Wirth: The national festival of the Germans in Hambach . Neustadt 1832, p. 14 ( Preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ Johann Georg August Wirth: The national festival of the Germans in Hambach . Neustadt 1832, p. 29 ( Preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ Johann Georg August Wirth: The national festival of the Germans in Hambach . Neustadt 1832, p. 34 ( Preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ Johann Georg August Wirth: The national festival of the Germans in Hambach . Neustadt 1832, p. 41 ( Preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ A b Johann Georg August Wirth: The national festival of the Germans in Hambach . Neustadt 1832, p. 48 ( preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Johann Georg August Wirth: The national festival of the Germans in Hambach . Neustadt 1832, p. 54 ( Preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Benjamin Krebs: Presentation of the main results from the investigations carried out in Germany because of the revolutionary plots of recent times . Federal President's Printing Office, Frankfurt am Main 1838, p. 25 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Benjamin Krebs: Presentation of the main results from the investigations carried out in Germany because of the revolutionary plots of recent times . Federal President's Printing Office, Frankfurt am Main 1838, p. 26 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ A b Johann Georg August Wirth: The national festival of the Germans in Hambach . Neustadt 1832, p. 94 ( preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Benjamin Krebs: Presentation of the main results from the investigations carried out in Germany because of the revolutionary plots of recent times . Federal President's Printing Office, Frankfurt am Main 1838, p. 23 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Benjamin Krebs: Presentation of the main results from the investigations carried out in Germany because of the revolutionary plots of recent times . Federal President's Printing Office, Frankfurt am Main 1838, p. 26 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Franz Xaver Remling: The Maxburg near Hambach . Schwan and Götz'sche Hofbuchhandlung, Mannheim 1844, p. 137 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

Individual evidence

- ^ Richard Schwemer, Historical Commission of the City of Frankfurt a. M .: History of the free city of Frankfurt a. M. (1814-1866) . tape 2 . J. Baer, o.r. 1912, p. 512 ff . ( Text archive - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Rüdiger Hachtmann: Reutlingen in the revolutionary years 1848/49 . Ed .: Heinz Alfred Gemeinhardt, Hermann Bausinger (= Reutlinger Geschichtsblätter . Volume 38 ). Stadtarchiv Reutlingen, Reutlinger Geschichtsverein, Reutlingen 2000 ( library.fes.de [accessed on January 25, 2013] Reviews from the archive for social history February 2002).

- ↑ Cf. Dieter Lent: Finding aid for the holdings of the estate of the democrat Georg Fein (1803–1869) and the Fein family (1737–) approx. 1772–1924 . Lower Saxony archive administration, Wolfenbüttel 1991, ISBN 3-927495-02-6 , p. 80 .

- ↑ Mathias Schmoeckel: In search of the lost order. 2000 years of law in Europe. Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar 2006, p. 597.

- ^ A b Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society 1815-1845 / 49 . IV edition. CH Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-32262-X , p. 363 ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Dieter Langewiesche: On the survival of the Old Empire in the 19th century. The composite state tradition . In: Andreas Klinger, Hans-Werner Hahn, Georg Schmidt (eds.): The year 1806 in a European context . Balance, hegemony and political cultures. Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2008, ISBN 978-3-412-19206-8 , pp. 126-128 .

- ^ Wiener Congreß – Acte, Paris Peace Treaties: Definitely – treatise between His Majesty the Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary and Bohemia, and Highest Allies on the one hand, then, His Majesty the King of France and Navarra on the other. Retrieved March 14, 2013 .

- ↑ GM Kletke (Ed.): The State Treaties of the Kingdom of Bavaria from 1806 up to and including 1858 . Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 1860, p. 310 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Ilja Mieck: Handbook of Prussian History. The 19th century and major themes in the history of Prussia . Ed .: Otto Büsch. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-11-008322-1 , p. 179 f . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society 1815–1845 / 49 . IV edition. CH Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-32262-X , p. 210 ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Hans-Werner Hahn, Helmut Berding: Handbook of German History / Reforms, Restoration and Revolution 1806–1848 / 49 . tape 14 . Klett-Cotta, 2009, ISBN 978-3-608-60014-8 , pp. 347 ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Thomas Nipperdey: German History 1800–1866. Citizen world and strong state . CH Beck, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-406-09354-X , p. 83 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Constitutional document of the Jena fraternity. In: Herman Haupt (Hrsg.): The constitution document of the Jenaische Burschenschaft of June 12, 1815 (= sources and representations on the history of the fraternity and the German unity movement. Volume 1). 2nd Edition. Heidelberg 1966, DNB 457866659 , pp. 114-161 (1st edition. Heidelberg 1910, OCLC 867829450 ).

- ↑ Max von Boehn: Biedermeier. Germany from 1815–1847 . European History Publishing House, Paderborn 2012, ISBN 978-3-86382-475-4 , pp. 21st ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society 1815–1845 / 49 . IV edition. CH Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-32262-X , p. 332 f . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Rudolf Stöber: German press history . II edition. UVK Verlagsgesellschaft, Konstanz 2005, ISBN 3-8252-2716-2 , p. 230 f . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ a b Max von Boehn: Biedermeier. Germany from 1815–1847 . European History Publishing House, Paderborn 2012, ISBN 978-3-86382-475-4 , pp. 48 ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society 1815–1845 / 49 . IV edition. CH Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-32262-X , p. 336 ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Erich Bauer : Schimmer book for young corps students. 4th edition. o. O., 1971, p. 7 ff.

- ^ Robert Gramsch: Erfurt - The oldest university in Germany: From general studies to university . Sutton Verlag, Erfurt 2012, ISBN 978-3-95400-062-3 , p. 17 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Wolfram Siemann: Deutsche Tribüne (1831-1832) . KG Saur, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-598-11543-1 , p. 457 f . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society 1815–1845 / 49 . IV edition. CH Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-32262-X , p. 64 ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Reinhard Rürup: Germany in the 19th Century, 1815-1871 . tape 8 . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1992, ISBN 3-525-33584-9 , pp. 164 f . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Wilhelm von Weber: The German customs union (history of its formation and development) . 2nd Edition. Veit & Comp, Leipzig 1871, p. 50 f . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Wilhelm Kreutz: Hambach 1832. German festival of freedom and harbinger of the European springtime . Ed .: State Center for Political Education Rhineland-Palatinate. Mainz 2007, p. 17 ( political-bildung-rlp.de [PDF; 783 kB ; accessed on January 12, 2013]).

- ^ Richard Schwemer, Historical Commission of the City of Frankfurt a. M .: History of the free city of Frankfurt a. M. (1814-1866) . tape 2 . J. Baer, o.r. 1912, p. 426 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive - further statements on Sauerwein on pp. 425-428, p. 520, p. 536, p. 603, p. 740).

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society 1815–1845 / 49 . IV edition. CH Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-32262-X , p. 348 f., p. 363 ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Wilhelm Kreutz: Hambach 1832. German festival of freedom and harbinger of the European springtime . Ed .: State Center for Political Education Rhineland-Palatinate. Mainz 2007, p. 12–14 ( political-bildung-rlp.de [PDF; 783 kB ; accessed on January 12, 2013]).

- ^ Wilhelm Kreutz: Hambach 1832. German festival of freedom and harbinger of the European springtime . Ed .: State Center for Political Education Rhineland-Palatinate. Mainz 2007, p. 18 ( political-bildung-rlp.de [PDF; 783 kB ; accessed on January 12, 2013]).

- ^ Wilhelm Kreutz: Hambach 1832. German festival of freedom and harbinger of the European springtime . Ed .: State Center for Political Education Rhineland-Palatinate. Mainz 2007, p. 8 ( political-bildung-rlp.de [PDF; accessed on January 12, 2013]).

- ^ Wilhelm Kreutz: Hambach 1832. German festival of freedom and harbinger of the European springtime . Ed .: State Center for Political Education Rhineland-Palatinate. Mainz 2007, p. 9 ( Politik-bildung-rlp.de [PDF; accessed on January 12, 2013]).

- ^ Wilhelm Kreutz: Hambach 1832. German festival of freedom and harbinger of the European springtime . Ed .: State Center for Political Education Rhineland-Palatinate. Mainz 2007, p. 9 f . ( political-bildung-rlp.de [PDF; accessed on January 12, 2013]).

- ^ A b Richard Schwemer, Historical Commission of the City of Frankfurt a. M .: History of the free city of Frankfurt a. M. (1814-1866) . tape 2 . J. Baer, o.r. 1912, p. 491 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive - further statements on Sauerwein on pp. 425-428, p. 520, p. 536, p. 603, p. 740).

- ↑ a b Wilhelm Kreutz: Hambach 1832. German freedom festival and harbinger of the European spring of nations . Ed .: State Center for Political Education Rhineland-Palatinate. Mainz 2007, p. 10 f . ( political-bildung-rlp.de [PDF; 783 kB ; accessed on January 12, 2013]).

- ↑ The Miracle on the Oder Lived European Neighborhood in Past and Present. ( MS Word ; 541 kB) Andrzej Stach, bpb, p. 23 , accessed on January 12, 2013 .

- ↑ Max von Boehn: Biedermeier. Germany from 1815–1847 . European History Publishing House, Paderborn 2012, ISBN 978-3-86382-475-4 , pp. 80 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ a b Wilhelm Kreutz: Hambach 1832. German freedom festival and harbinger of the European spring of nations . Ed .: State Center for Political Education Rhineland-Palatinate. Mainz 2007, p. 13 ( political-bildung-rlp.de [PDF; 783 kB ; accessed on January 12, 2013]).

- ^ A b Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society 1815-1845 / 49 . IV edition. CH Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-32262-X , p. 362 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society 1815–1845 / 49 . IV edition. CH Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-32262-X , p. 357 f . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Elisabeth Hüls: The German Tribune 1831/32. Political press and censorship . In: Nils Freytag, Dominik Petzold (Ed.): The 'long' 19th century. Old questions and new perspectives (= Munich contact study history. Münchner Universitätsschriften . Volume X ). Herbert Utze Verlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-8316-0725-9 , pp. 35 ( Preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Elisabeth Hüls and Hedwig Herold Schmidt: Volume 2: Presentation, commentary, glossary, register, documents, by Elisabeth Hüls and Hedwig Herold-Schimdt (new version of the original with extensive commentary volume) . In: new ed. by Wolfram Siemann and Christof Müller-Wirth, Johann Georg August Wirth (eds.): Deutsche Tribüne (1831–1832) . KG Saur, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-11-095402-9 , p. 40-64 .

- ↑ a b Elisabeth Hüls and Hedwig Herold Schmidt: Volume 2: Presentation, commentary, glossary, register, documents, by Elisabeth Hüls and Hedwig Herold-Schimdt (new version of the original with extensive commentary volume) . In: new ed. by Wolfram Siemann and Christof Müller-Wirth, Johann Georg August Wirth (eds.): Deutsche Tribüne (1831–1832) . KG Saur, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-11-095402-9 , p. 48 f .

- ↑ Eike Wolgast : Festivals as an expression of national and democratic opposition - Wartburg Festival 1817 and Hambach Festival 1832. (PDF; 139 kB) (No longer available online.) P. 7 , archived from the original on February 4, 2014 ; Retrieved on March 18, 2013 ([annual edition] of the Society for Burschenschaftliche [historical research] 1980/81/1982, edited by Horst Bernhardi and Ernst Wilhelm Wreden , o. O./o. J., pp. 41-71).

- ↑ a b Wilhelm Kreutz: Hambach 1832. German freedom festival and harbinger of the European spring of nations . Ed .: State Center for Political Education Rhineland-Palatinate. Mainz 2007, p. 19 ( political-bildung-rlp.de [PDF; 783 kB ; accessed on January 12, 2013]).

- ↑ Elisabeth Fehrenbach: Constitutional State and Nation-Building 1815–1871 . Encyclopedia of German History. tape 22 . Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-486-58217-8 , p. 14 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Elisabeth Hüls: The German Tribune 1831/32. Political press and censorship . In: Nils Freytag, Dominik Petzold (Ed.): The ›long‹ 19th century . Old questions and new perspectives (= Munich contact study history. Münchner Universitätsschriften . Volume X ). Herbert Utze Verlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-8316-0725-9 , pp. 34 ( Preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Hans-Werner Hahn, Helmut Berding: Handbook of German History / Reforms, Restoration and Revolution 1806–1848 / 49 . tape 14 . Klett-Cotta, 2009, ISBN 978-3-608-60014-8 , pp. 446 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Hans-Werner Hahn, Helmut Berding: Handbook of German History / Reforms, Restoration and Revolution 1806–1848 / 49 . tape 14 . Klett-Cotta, 2009, ISBN 978-3-608-60014-8 , pp. 447 ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Wilhelm Kreutz: Hambach 1832. German festival of freedom and harbinger of the European springtime . Ed .: State Center for Political Education Rhineland-Palatinate. Mainz 2007, p. 19th f . ( political-bildung-rlp.de [PDF; 783 kB ; accessed on January 12, 2013]).

- ^ Wilhelm Kreutz: Hambach 1832. German festival of freedom and harbinger of the European springtime . Ed .: State Center for Political Education Rhineland-Palatinate. Mainz 2007, p. 20 ( political-bildung-rlp.de [PDF; 783 kB ; accessed on January 12, 2013]).

- ^ Wilhelm Kreutz: Hambach 1832. German festival of freedom and harbinger of the European springtime . Ed .: State Center for Political Education Rhineland-Palatinate. Mainz 2007, p. 21st f . ( political-bildung-rlp.de [PDF; 783 kB ; accessed on January 12, 2013]).

- ^ Ludwig Börne: All writings. Volume 5, p. 249 ff .: Ludwig Börne letters. Retrieved December 11, 2012 .

- ↑ Cockade 150th anniversary. Stadt Neustadt, accessed on December 14, 2012 .

- ^ Sale of cockades in 1832. (No longer available online.) In: strasse-der-demokratie.eu. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015 ; Retrieved December 13, 2012 .

- ↑ a b c Wilhelm Kreutz: Hambach 1832. German festival of freedom and harbinger of the European spring of nations . Ed .: State Center for Political Education Rhineland-Palatinate. Mainz 2007, p. 23 ( political-bildung-rlp.de [PDF; 783 kB ; accessed on January 12, 2013]).

- ↑ a b c Wilhelm Kreutz: Hambach 1832. German festival of freedom and harbinger of the European spring of nations . Ed .: State Center for Political Education Rhineland-Palatinate. Mainz 2007, p. 22 ( political-bildung-rlp.de [PDF; 783 kB ; accessed on January 12, 2013]).

- ^ Wilhelm Kreutz: Hambach 1832. German festival of freedom and harbinger of the European springtime . Ed .: State Center for Political Education Rhineland-Palatinate. Mainz 2007, p. 22nd f . ( political-bildung-rlp.de [PDF; 783 kB ; accessed on January 12, 2013]).

- ^ Johann Georg Krünitz: economic-technological encyclopedia . tape 195 . Paulische Buchhandlung, Berlin 1848, p. 89 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ a b c d Wilhelm Kreutz: Hambach 1832. German festival of freedom and harbinger of the European spring of nations . Ed .: State Center for Political Education Rhineland-Palatinate. Mainz 2007, p. 24 ( political-bildung-rlp.de [PDF; 783 kB ; accessed on January 12, 2013]).

- ↑ Hubert Freilinger: "The Hambachers". Participants and sympathizers of the near revolution of 1832 . In: ZBLG . tape 41 , 1978, p. 712 ( periodika.digitale-sammlungen.de ).

- ↑ a b c Wilhelm Kreutz: Hambach 1832. German festival of freedom and harbinger of the European spring of nations . Ed .: State Center for Political Education Rhineland-Palatinate. Mainz 2007, p. 30 ( political-bildung-rlp.de [PDF; 783 kB ; accessed on January 12, 2013]).

- ↑ Elisabeth Fehrenbach: Constitutional State and Nation-Building 1815–1871. Encyclopedia of German History . tape 22 . Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-486-58217-8 , p. 14 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society 1815–1845 / 49 . 4th edition. Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-32262-X , p. 365 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Hubert Freilinger: "The Hambachers". Participants and sympathizers of the near revolution of 1832 . In: Journal for Bavarian State History . tape 41 , 1978, p. 713 ( periodika.digitale-sammlungen.de ).

- ↑ Hans-Werner Hahn, Helmut Berding: Handbook of German History / Reforms, Restoration and Revolution 1806–1848 / 49 . tape 14 . Klett-Cotta, 2009, ISBN 978-3-608-60014-8 , pp. 447 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Hubert Freilinger: "The Hambachers". Participants and sympathizers of the near revolution of 1832 . In: Journal for Bavarian State History . tape 41 , 1978, p. 721 ( periodika.digitale-sammlungen.de ).

- ↑ a b c Harald Lönnecker : 175 years of the Hambach Festival. Retrieved November 29, 2012 .