Cemetery of the March Fallen

The cemetery of the March fallen is a cemetery in the Volkspark Friedrichshain in the Berlin district of Friedrichshain . It was created for the victims of the March Revolution of March 18, 1848, those who fell in March . In 1925, the Berlin architect Ludwig Hoffmann redesigned the facility and brought it into the existing three-sided form. Further redesigns took place in 1948 and 1957.

After the November Revolution of 1918, the first Berlin fallen soldiers of this uprising were buried here, of which the bronze figure Red Sailor by Hans Kies , erected in 1960 , is intended to commemorate.

In 1948, a memorial stone with the names of those who fell in March was erected to mark the 100th anniversary of the cemetery . Today there are still 18 grave slabs, three iron grave crosses, a stele and two grave monuments made of cast iron . The cemetery of those who fell in March is now a memorial and a garden monument.

history

Preparations and burial 1848

The first buried in the cemetery of the March dead were 183 civilian victims of the barricade fighting of the March Revolution of March 18, 1848. They were buried on March 22, 1848 on the Lindenberg, the then highest elevation of the Volkspark, which was still under construction, popularly known as Kanonenberg was buried.

Based on a motion by City Councilor Daniel Alexander Benda, the Berlin City Council made the decision to build the new cemetery on a 2.3 hectare area the day before the funeral. It stipulated that in addition to the civilian victims, the fallen soldiers should also be buried here. The decision to have a common funeral had already been widely discussed in the population and mostly rejected, but ultimately the military decided by not making the bodies of the dead soldiers available. The two windmills located on the Lindenberg at the time were to be demolished for the construction of the burial site. In addition, a memorial was to be erected on the cemetery, which was not yet part of the Berlin urban area, and another in the city. Despite this decision, only one mill was demolished and the area was therefore considerably smaller. The second mill burned down in 1860. The burial of the soldiers did not take place here either, but only on March 24th at the Invalidenfriedhof in Berlin-Mitte . The planned monuments were also not erected. The cemetery was originally laid out as a square with diagonal paths that led to a circumferential path on which the graves were located. The center of the complex was a roundabout with a summer linden tree .

After a private farewell opportunity on March 21, the funeral took place on March 22. On this day a pageant was prepared and all of Berlin, including the Berlin City Palace and the Scharnhorst and Blücher monument in the city center, were decorated in black, red, gold and black. Helpers decorated the coffins of the fallen with flowers from the royal garden. On the Gendarmenmarkt it came to laying out the March Dead . There were 100,000 people gathered, Adolf Glaßbrenner even spoke of 300,000. In the New Church, the church at the German Cathedral on Gendarmenmarkt, the relatives of the dead gathered for a Protestant service. Those present sang the chant Jesus My Confidence , after which they left the church. The Protestant preacher of the New Church Adolf Sydow , the Catholic chaplain Johann Nepomuk Ruhland from the Sankt-Hedwigs-Kirche and the Rabbi Michael Sachs held a short consecration speech in front of the door, an interreligious meeting which the royal privileged Berlinische Zeitung commented as follows: " it was a historical moment that is as unprecedented in history as this whole solemnity itself ”.

The procession from the New Church to the cemetery consisted of 20,000 participants and 3,000 stewards, was about 7.5 kilometers long and lasted four hours. The royal privileged Berlinische Zeitung (later Vossische Zeitung ), the entire editorial staff of which attended the funeral, remarked that the symbols “seemed to embody the whole history of our fatherland”. The participants carried flags from other cities as well as from individual trades in the city. Medals and uniforms, however, were hardly available. As agreed before , the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV took off his helmet on the balcony on the way across Berlin's Schloßplatz .

Adolf Sydow was the first to preach in the cemetery, followed by Assessor Georg Jung , the spokesman for the Berlin Democrats, who also gave a speech. In the weeks that followed, other victims of the fighting who died from their injuries were interred on the site. The final number of graves rose to 254.

1848-1849

The cemetery of those who fell in March became a symbol of the German democracy movement from 1848 onwards . The facility regularly represented an important memorial and demonstration site.

In June 1848 there was a first demonstration of Berlin students at the graves at this location, in which around 100,000 people took part. They wanted to commemorate the dead and at the same time exhort the rulers not to prematurely undo the changes made during the revolution. A letter from the students to the magistrate shows this:

"The tendency of the procession is to respond to the often-mentioned disapproval and hereticization of a revolution to which we owe the completion of our political rights, and to honor the wounded names of the fallen."

As early as March 25, 1848, a public announcement in various Berlin newspapers asked for donations and drafts for a memorial in the cemetery, for which the foundation stone was to be laid on the anniversary of the revolution . This appeal was addressed to the entire German people, pointing out that the March Revolution was of a national nature and that the Berliners alone were not responsible. The money received for the committee for the construction of the monument was administered by the merchant and shoe manufacturer F. H. Bathow. Since this committee was not approved by the authorities, Bathow was police forced to surrender the money. The whereabouts and the sum of the collected money remained unclear, after contradicting reports it was either deposited with the city court in 1854 or was transferred to the pension fund of the policemen.

Because of the confiscation of the money, there was no memorial for the anniversary of the revolution. On this date not even all graves were decorated with simple wooden crosses and the city government did not want to finance them. So the Berliners brought up the missing 60 crosses through a spontaneous collection between March 18 and 22, 1849.

Due to the political developments up to the first anniversary of the revolution, both the magistrate and the city council expected renewed uprisings in Berlin. For this reason the manning of the military and the police was massively increased. The royal privileged Berlinische Zeitung wrote on March 20, 1849:

“As early as the 17th, the city itself presented a completely warlike appearance, and all measures had been taken, as they can only occur in a state of siege. Significant troops were encamped in all the villages and suburbs around Berlin (...). The Friedrichshain in front of the Landsberger Tor was particularly strong. The few buildings at the entrance to Friedrichshain were filled with soldiers down to the smallest rooms (...) Large detachments of dragoons patrolled all roads, and the Friedrichshain was also guarded by a detachment of policemen. "

Despite this presence of the military and police, thousands marched to the graves of those who died in March on March 18. These were mostly workers. The graves had already been decorated with flowers the previous night and employees of the Borsigwerke set up a steel column at each of the four corners of the cemetery , which was equipped with two torches. In the afternoon of the day, the feared clashes between the demonstrators and the protection guards actually took place, but the outcome was relatively minor.

When Otto von Bismarck visited the cemetery in September 1849 , he wrote bitterly to his wife:

“Yesterday I was with Malle [Malwine von Arnim-Kröchlendorff, sister of Bismarck] in Friedrichshain, and I could not even forgive the dead, my heart was full of bitterness over the idolatry with which the graves of these criminals, where every inscription on the cross of "Freedom and Justice" boasted, a mockery of God and people. I tell myself, we are all in sin, and God alone knows how to tempt us; but my heart swells with poison when I see what they have made of my fatherland, these murderers, with whose graves the Berliners still practice idolatry today. "

From 1850 to 1900

In order to avoid riots in the following years, the Prussian State Ministry forbade entering the cemetery on March 18, 1850 and on the anniversaries of the following years. On March 17th, 1850, all entrances were cordoned off by the police. On the same day and the following day, workers arrived at the park and tried to get to the cemetery to lay flowers and wreaths. The commemorative events then took place in the surrounding garden bars, and clashes between the police and the demonstrators continued this year.

On March 20, 1850, the royal privileged Berlinische Zeitung announced that the cemetery of the March dead should be leveled and that the buried should be relocated. The square should give way to a train station . However, this announcement was never realized, and so many workers came to the cemetery on March 18, 1851. This day ended again in riots, which this time did not end without injuries. By March 18, 1852, all paths to the cemetery, with the exception of the main path from Landsberger Tor, were planted with flowers and thus made impassable. In the run-up to the Cologne communist trial , however, 10,000 demonstrators came to the park this year and again the day ended in violence. From 1853 the entire park was cordoned off with a high wooden fence, later a bar fence. In this way, the authorities prevented a meeting at the cemetery that year.

The planned construction of the station was not reported again until February 1854, after the construction of an orphanage on the edge of the park was rejected in 1853 on the grounds that the sight of the cemetery could remind the youth of the March Revolution of 1848 every day and thus lead to rebellion again. There was no relocation here either, and until 1856 a number of people gathered at the cemetery every year to commemorate the revolution and the fallen. In a letter dated October 22, 1856, the police chief of Berlin requested the city's magistrate to make access to the cemetery impossible by planting a thorny hedge, "with the intention of letting that place fall into oblivion." rejected these plans and again proposed a repositioning of the dead, to which the police chief approved, provided that this should be done without causing a major stir.

In October 1857 the press, and thus the public, became aware of the plans of the magistrate through relatives of the dead, from whom the magistrate wanted to obtain approval for the transfer of the dead against payment of funds. In September 1858, the city council submitted a plan to move the city council as soon as possible, which it also decided. As a result, an unknown number of coffins were also excavated, but a complete relocation did not take place. On May 15, 1861, the Königlich-Privilegierte Zeitung announced that access to the cemetery was again permitted without restriction.

Between 1868 and 1874 the Friedrichshain municipal hospital was built on Landsberger Allee in the immediate vicinity of the cemetery. Since then, the cemetery itself has been located directly on the hospital wall, separated from the rest of the Volkspark by the access road to the main entrance of the hospital. The next important date for the cemetery was March 18, 1873, the 25th anniversary of the revolution. At the same time, this day became a day of remembrance for the Paris Commune of 1871. A large crowd flocked to and in the cemetery of the March fallen, and the anniversary led to renewed clashes between demonstrators and the police. This had the park forcibly evicted in the late afternoon. In the following years the cemetery was visited by thousands of visitors every year, mainly by communist and social democratic workers. Local politicians and the Social Democratic parliamentary group in the Reichstag also repeatedly honored the dead by laying wreaths.

Before the 50th anniversary in 1898 there was a dispute between the city authorities and the Berlin Police Headquarters over the redesign of the cemetery; the historian Helke Rausch calls the behavior on the part of the monarch and the authorities "massive obstruction". In March 1895, the General Workers' Association of Berlin resumed the plans from 1848 in a resolution and called for a memorial to be erected for the "fighters" of 1848. The city council approved the erection of a representative entrance portal with an iron gate in the cemetery, for which Ludwig Hoffmann submitted a draft, while the President of the Province of Brandenburg, Heinrich von Achenbach , expressed concerns if the Berlin magistrate took part in honoring the insurgents . In January 1898, the Berlin magistrate rejected the submission under pressure from the Council of Ministers, against which the city council protested and filed a complaint with the Higher Administrative Court - unsuccessfully, so that the “reactionary” view of the authorities prevailed. The dispute arose again in 1899 when a plaque was proposed to be placed at the entrance portal instead of a memorial. The police headquarters now refused the building permit on the grounds that "... the building is intended to honor those who were buried there in March, i.e. a political demonstration to glorify the revolution, which cannot be permitted for general reasons."

A tribute to those who died in March was still refused, and the cemetery was brought into an "orderly" state without reference to its historical peculiarity. With reference to these disputes over the monument, the inscription on the wreath of the social democratic group of city councilors read:

"You have set your own monument."

The Marxist historian Franz Mehring summarized the history of the cemetery empathically in his History of Social Democracy in 1897/1898 :

“[The bourgeoisie] has betrayed [the work of March 18], and their bad conscience left the cemetery where the fallen people's fighters were laid to rest. The rust gnawed at the letters and numbers on the crosses, and the grass blew together over the sunken burial mounds. But then the day came when the proletariat's awakened class consciousness understood the historical significance of the March Revolution and rededicated the Friedrichshain cemetery. "

1900 to 1945

In 1908, the 60th anniversary of the cemetery, the anniversary coincided with the political dispute over voting rights in Germany. In March, at the graves of those who died in March, the Social Democrats passed their resolution on this subject as a March resolution , in which they called for universal, equal, secret and direct suffrage in Germany. Wreaths were laid in the cemetery and several thousand people had gathered here. The bows on the wreaths in particular pointed to the demands of the people and especially to the demands for the right to vote. For example, on one of the wreaths placed by the editorial staff of the Vorwärts newspaper , the dedication “The first campaigners to vote” was to be read. The police removed around 60 loops based on the labels, which resulted in rioting by visitors against the police.

On March 18, 1917, the traditional annual workers' walk to the graves was combined with an expression of solidarity with the February Revolution in Russia .

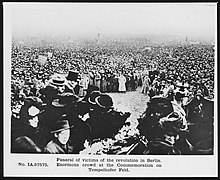

In November of the following year 1918 there was also a revolution in Germany that became known as the November Revolution . On November 20, eight dead from these uprisings were buried in a separate grave area in the cemetery of the March fallen in order to illustrate and underpin the connection between the two revolutions. The funeral, at which some speakers emphasized the parallels between the two revolutions, took place on the Tempelhofer Feld ; Several thousand people took part in it and in the following funeral procession. An honorary company from the Alexander Regiment led the procession, followed by a large number of wreath-bearers, representatives of the Reich, state and city authorities, the Social Democratic Party and the trade unions . Then came the wagons with the coffins and the relatives of the fallen, as well as a special company of sailors . The workers followed with red and black flags. When the first coffin was let into the pit around 3:00 p.m., Emil Barth ( USPD ) held the funeral speech for the people 's representatives for the Council of People's Representatives , Luise Zietz (USPD) and Karl Liebknecht also spoke .

“Let's not be mistaken. Even the political power of the proletariat, insofar as it fell to it on November 9th, has largely melted away today and continues to dissipate from hour to hour (...) Hesitation delays death - the death of the revolution "

From December 6 to 11, 1918, there were conflicts with counter-revolutionary troops in Berlin. In a violent confrontation on December 6th in the area of Invalidenstrasse , 16 revolutionaries were killed, including members of the Red Soldiers' Union (see Red Front Fighter League ). Willi Budich , a leading member of the Spartakusbund and one of the two chairmen of the Soldiers' Union, was wounded. The victims of this attack were also buried in the cemetery on December 21st. On December 24th, there was an attack by government troops on the People's Navy Division, which was stationed in the Berlin City Palace and was considered Spartacist . In the successful defensive battles of the sailors, eleven people were killed, who were buried on December 29th in a third pit in the cemetery of the March dead.

In January 1919, the KPD and USPD applied for the burial of 31 dead from the Spartacus uprising in the cemetery of those who fell in March, including Karl Liebknecht . Since the magistrate refused this honor, these victims of the revolution were buried in the central cemetery in Friedrichsfelde .

In the Weimar Republic , workers, but also representatives of the SPD, the KPD, the trade unions and the Reichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Gold visited the cemetery every year as a memorial .

At the beginning of the 1920s, the Friedrichshain district council meeting decided with a majority of votes from the SPD and KPD to give the cemetery a "dignified appearance". This mainly related to the redesign of the entrance gate based on a model by Ludwig Hoffmann. On October 11, 1925, Hoffmann's new gate was officially inaugurated as his last construction project and with a rally in honor of the "fighters for German freedom" (address by District Mayor Mielitz). According to the newspaper Vorwärts , this took place with the participation of a "large crowd". Before the unveiling of the new portal, 10,000 men of the Berlin comradeship of the Reich Banner passed it with lowered flags and drum rolls. At this point in time, Hoffmann had not been in office as urban planning officer for the city of Berlin for a year. The gate was forged from iron and held on both sides by pillars, on which the figure of the Greek god of death Thanatos leaned on a lowered torch, kneeling and naked . The Forward wrote:

“The simple, almost sparse measuredness of the republican outlook is also expressed in the new gate, which (...) finally opens the entrance to the small cemetery of the March fallen in Friedrichshain in a dignified manner. A simple portal made of hard stone and tough iron, designed by an artist's hand, will be presented to the public. "

In addition, the remaining tombstones and crosses were arranged on three sides of the cemetery in the manner that can still be seen today.

During the National Socialist regime , the cemetery was hardly noticed and was forgotten by large parts of the population. Public honoring of those who died in the revolutions could lead to political persecution, and social democratic and communist opponents of the Nazis also stayed away out of fear.

After 1945

After the end of the Second World War , the cemetery also became more popular again. In 1947 the Berlin magistrate drew up a design for the 100th anniversary of the revolution and, above all, for the redesign of the cemetery. The Friedrichshain District Office suggested removing the narrow paths in the cemetery in favor of a central meeting place and placing a memorial stone in the center. The decorated gate based on Hoffmann's template still existed at this time and should be replaced with a simpler variant during this redesign. Instead, however, only the decorative figures were removed for the time being: "Only the entrance gate requires a slight redesign, with the loss of its not very beautiful figural decoration."

On March 18, 1948, at the beginning of the celebrations, the new memorial stone was unveiled in a central location. The area had been planted with lawn, and a narrow path led to the memorial stone. The back of the stone by Peter Steinhoff is inscribed with the names of 249 people who fell in March of 1848. The front of the stone reads:

“The dead 1848/1918. You erected the monument yourself - only a serious warning speaks from this stone / That our people never renounce what you died for - to be united and free. "

The cemetery was redesigned again in 1956/57 in preparation for the 40th anniversary of the November Revolution. Under the direction of Franz Kurth , the western part was equipped with three grave slabs as memorial stones for the victims of 1918. The gate has now also been replaced by a new, four-meter-wide entrance gate to what was then Leninallee . In 1960, the bronze figure Red Sailor , made by the Berlin sculptor Hans Kies , was placed in front of the entrance . Larger than life, she depicts an armed sailor from the November Revolution.

During the entire GDR period, memorial ceremonies and wreath-laying ceremonies took place in the cemetery every year, but these were rarely sensational. Independently of this, since 1979 the West Berlin initiative Aktion 18. March organized an annual wreath-laying ceremony in the cemetery, which the GDR authorities did not like to see but tolerated.

The cemetery since 1990

Since 1992 there have been commemorations organized jointly by the responsible district office and the initiative, at which the President of the Berlin House of Representatives traditionally lays a wreath.

The cemetery of the March fallen is in the southern part of the Volkspark Friedrichshain and, due to its somewhat remote location, is one of its quietest parts. It is separated from the rest of the park by the access road to the hospital, Ernst-Zinna-Weg. This was named on March 18, 2000 after the journeyman locksmith Ernst Zinna , who died on March 19, 1848 as a result of the fighting. The cemetery is rectangular, about 30 × 40 meters in size and is surrounded by a low stone wall. From the original inventory, 18 stone grave slabs, three iron grave crosses, a stele and two grave monuments have been preserved. You are in the three-sided surrounding beds, which are planted with bushes and trees. In the center of the complex is the memorial stone, unveiled in 1948, the back of which bears the names of 249 people who died in March, supplemented by the addition of “an unknown”. Some of the names on the surviving tombstones differ from those on the memorial stone. The three grave slabs for the victims of the November Revolution are in the western part of the complex. While the left is covered with a saying by Karl Liebknecht and the right with a saying by Walter Ulbricht , the middle 33 bears the names of victims of the November Revolution , the most famous of which is Erich Habersaath , who was the first Berlin victim of the November Revolution to be shot on November 9, 1918 has been. On the southwest corner of the wall surrounding the cemetery is the bronze sculpture of the Red Sailor.

Since May 29, 2011 there has been an exhibition on the Berlin March Revolution and the history of the cemetery organized by the Paul Singer Association in front of and on the cemetery. In front of the cemetery a 30-meter-long sea container was set up, which serves as an exhibition pavilion for the March Revolution and as an information office. In the cemetery there are circular information boards about the history of the cemetery.

On September 3, 2018, the first part of a permanent exhibition on the 1918/1919 revolution ( November Revolution ) opened on the occasion of the 100th anniversary .

See also

literature

- Heike Abraham: The Friedrichshain. The history of a Berlin park from 1840 to the present (= miniatures on the history, culture and preservation of Berlin monuments. Volume 27). Kulturbund der DDR, Berlin 1988.

- Kathrin Chod, Herbert Schwenk, Hainer Weißpflug: Berlin district lexicon Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg. Haude & Spener, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-7759-0474-3 .

- Hans Czihak: The struggle for the design of the cemetery of the March fallen in Berlin's Friedrichshain. In: Walter Schmidt (Ed.): Democracy, Liberalism and Counterrevolution. Studies on the German Revolution of 1848/49. Berlin 1998, pp. 549-561.

- Jan Feustel : Vanished Friedrichshain. Buildings and monuments in the east of Berlin. Edited by the Heimatmuseum Friedrichshain. Agit-Druck, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-935810-01-6 .

- Manfred Hettling: Cult of the dead instead of revolution. 1848 and its victims. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1998, ISBN 3-10-029409-2 .

- Kurt Laser, Norbert Podewin , Werner Ruch, Heinz Warnecke: The cemetery of the March fallen in Berlin's Friedrichshain - the burial place of the victims of two revolutions. trafo, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-86464-096-4 .

- Heike Naumann: The Friedrichshain. History of a Berlin park. Heimatmuseum Friedrichshain, Berlin 1994.

- Heinz Warnecke: Commemoration of the revolutionary victims of 1848 and 1918. On the culture of remembrance at the March fallen cemetery in Friedrichshain since 1918. In: Christoph Hamann, Volker Schröder (ed.): Democratic tradition and revolutionary spirit. Remembering 1848 in Berlin (= History. Volume 56). Centaurus, Herbolzheim 2010, ISBN 978-3-8255-0762-6 , pp. 104-119.

- Folkwin Wendland: Berlin's gardens and parks. From the foundation of the city to the end of the nineteenth century. Propylaea, Frankfurt am Main u. a. 1979, ISBN 3-549-06645-7 .

- Christine Strotmann: Forgotten Revolutionaries. The cemetery of the March fallen . Military history 1/2018, pp. 10–13.

Web links

- Cemetery of those who fell in March andSculpture "Red Sailor" . Entries in the Berlin State Monument List with further information.

- Heinz Warnecke: Cemetery of the March Fallen. In: Berlin.de , November 17, 2015.

- 1848: Cemetery of those who fell in March , project to develop a national memorial for the Paul Singer Association in cooperation with the Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg district office.

- Elegy to those who fell on March 18 and 19, 1848. March 22, 1848, urn : nbn: de: kobv: 109-1-5256283

Individual evidence

- ^ Dorlis Blume: March 1848 - Revolution in Berlin. In: Lebendiges Museum Online , March 2012.

- ↑ Bathow, FH In: General housing gazette for Berlin, Charlottenburg and surroundings , 1848, part 1, p. 18. “Merchant and shoe manufacturer”.

- ↑ Königlich privilegirte Berlinische Zeitung , No. 67, March 20, 1849, p. 2 f.

- ↑ Herbert von Bismarck : Prince Bismarck's letters to his bride and wife . Stuttgart 1919, pp. 143-144 (September 16, 1849).

- ↑ Helke Rausch: cult figure and nation. Public monuments in Paris, Berlin and London 1848–1914. Oldenbourg, Munich 2006, p. 93 .

- ↑ Quoted from Franz Mehring: Historical essays on Prussian-German history. Berlin 1946, p. 181 f.

- ↑ Karena Kalmbach: Ebert and December 6th. In: Novemberrevolution.de , 2002.

- ↑ On the cornerstone of democracy. The revolution of 1848 and the cemetery of the March dead. Exhibition by the Paul Singer Association, accessed on April 28, 2015.

- ^ District office Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg . ( focus.de [accessed on August 31, 2018]).

Coordinates: 52 ° 31 ′ 28 " N , 13 ° 26 ′ 11" E