Ludwig Hoffmann (architect)

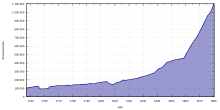

Ludwig Ernst Emil Hoffmann (born July 30, 1852 in Darmstadt ; † November 11, 1932 in Berlin ) was a German architect and from 1896 to 1924 city planner in Berlin. It shaped the architecture of Berlin at a time when the capital was growing rapidly. He was able to plan and realize numerous public administration buildings, schools , bridges , swimming pools , hospitals and other urban buildings. In his memoirs, Hoffmann named 300 buildings in 111 construction sites, in fact he built more. Typical of his work were the establishment of the Virchow Clinic , the sanatoriums in Berlin-Buch , 69 schools and public swimming pools such as the Baerwaldbad . Hoffmann's work as town planning officer included the period of economic upswing and growth in the German Empire , the First World War and the November Revolution of 1918, as well as the years of inflation .

Hoffmann's first building was the Imperial Court in Leipzig . Coming from the late Schinkel School, Hoffmann pursued a style of modern historicism . Hoffmann used historical forms, but often put them together in an unorthodox way. He often adopted these forms from the Italian Renaissance or the Italian Baroque , and later also from the North German Renaissance. Contemporaries praised the clarity and simplicity of his buildings. Hoffmann himself attached great importance to the individual design of each individual building and an artistic and technical penetration of all details. He rejected the formal language of architectural modernism as well as its industrial production methods.

Julius Posener summarized his work as “the most mature and richest expression of the 'official' endeavors of the time. […] Hoffmann was not a man of L'art pour l'art . The beauty of his schools, baths and hospitals was part of the social reform. ” Wolfgang Schächen described him as a bourgeois man of the German Empire. He wanted to pacify the empire through his buildings, not overcome it. During the Weimar Republic , Hoffmann quickly came into conflict with modernist architects and was largely forgotten shortly after his death. Critics accused him of eclecticism and mediocrity. It was not until the late 1970s that it was noticed more strongly again, triggered by Posener and Schächen.

family

Hoffmann was born in Darmstadt as the son of the national liberal Reichstag member Carl Johann Hoffmann and his wife Mathilde. The mother died in childbed when Ludwig Hoffmann was six years old. A year later the father married again. Hoffmann had six siblings, mostly step-siblings. According to Hoffmann, his stepmother prepared "a youth for us as I wish every child." Ludwig's father Carl Johann worked full-time as a lawyer and, in addition to his mandate in the Reichstag, was at times also a member of the Hessian state parliament and president of the second chamber of the state parliament. Hoffmann described his childhood and youth as growing up in civic security. Despite its wealth, the house was characterized by a simple, humble lifestyle. Hoffmann later noted that his parents and grandparents had taught him to make himself useful to society. His stepmother died in 1874 giving birth to their fourth child. The father died of a heart attack eight weeks later.

Ludwig Hoffmann's grandfather Emil Hoffmann came from a humble background and made fortunes as an entrepreneur. In doing so, he supported, among other things, the wars of liberation against Napoleon and the Greek struggle for freedom. Emil Hoffmann was temporarily a member of the second chamber of the Hessian state estates until the Hessian state government had him removed from this chamber.

Youth and education

In his childhood, Hoffmann made friends with the neighbor boy Alfred Messel . Both went to the Schmitzsche School together and later to the Ludwig-Georgs-Gymnasium . While it was clear to Messel early on that he wanted to become an artist, Hoffmann seemed to be undecided for a longer period of time. In his youth he still spoke of possible careers in law or as a chemist. In the end, he and Messel decided to train as an architect after graduating from high school in 1870 and as a one-year volunteer in the military. Hoffmann received his training together with his childhood friend Alfred Messel from 1874 at the Berlin Building Academy . Hoffmann later named Friedrich Adler , Richard Lucae , Julius Raschdorff and Johann Heinrich Strack as important influencing partners there. He passed his exam at Strack's. Hoffmann and Messel were both active in the Academic Association Motiv . They lived together throughout their studies and also worked together on most of the projects.

The training included a year of practical training as a "Baueleve", which Messel and Hoffmann spent in Kassel. There they spent most of the time making transcripts. An activity that neither gave them pleasure nor did they find it particularly instructive. In 1879 Hoffmann passed the first state examination at the building academy on the third attempt . After Messel had won the Schinkel Competition of the Berlin Architects' Association in 1881 , Hoffmann also took part in the Schinkel Competition in 1882 together with Bernhard Sehring and won it with a design for the Berlin Museum Island . With the prize, Messel undertook a trip to Italy for educational purposes, which Hoffmann also completed a short time later when he won the competition.

While Hoffmann and Messel's professional and private careers were the same until the 1890s, they parted ways afterwards. The separate participation in the Schinkel competition was the first point at which both went their own way. While Messel has been working alone since then, Hoffmann continued to get partners like Peter Dybwad and finally decided on a career in civil service. After a brief interlude in science, Messel became one of the first successful private architects .

The two remained closely connected in private. So they lived in the same Berlin house at the turn of the century. It was in this house that Hoffmann met his future wife Maria Weißbach, whom he married in 1895.

First practical experience

In accordance with the study regulations at the time, Hoffmann had to work for four years in order to acquire the second state examination. He joined the Franz Schwechten office in Berlin in 1879 and became government building supervisor there . In this position he was busy with the technical work for the construction of the War Academy in Dorotheenstrasse . On February 21, 1884, Hoffmann passed the second state examination, which qualified him as a government builder . His independent career began in the 1880s when he won the competition for the Imperial Court Building in Leipzig together with Peter Dybwad . The work on this building took ten years.

Imperial Court

Preliminary work

Hoffmann took second place in the Schinkel competition in 1882 with his design for the development of Berlin's Museum Island . The jury particularly praised the clarity of the execution. The award included a grant for a trip to Italy. Hoffmann traveled with Peter Dybwad via France and Switzerland to Naples, Pompeii, Rome, Florence, Siena and Genoa. On their return trip, Hoffmann and Dybwad took a three-month break in Munich, during which they took part in the competition for the newly built Reichsgericht in Leipzig. While Hoffmann's early student theses were still strongly influenced by classicism in the successor to Schinkel , as prevailed at the Berlin Bauakademie, he used a different design for the draft of the Imperial Court. After Paul Wallot had won the competition a little earlier with his plan for the Reichstag building , which was based on the Italian late Renaissance , Hoffmann now also resorted to their repertoire of forms. On the further trip the two learned on May 15, 1885 in Ferrara that, to their great surprise, "in recognition of the simplicity and clarity achieved by the authors" they had won first prize in the competition for the construction of the Imperial Court.

Realization and recognition

Hoffmann was 35 years old, had not yet completed a single building in a managerial capacity and was now entrusted with the construction of one of the most important buildings of the German Empire. In contrast to his previous tasks, he was able to work comparatively freely here. The Prussian Ministry for Public Works, for which Hoffmann was formally active at the time, had restricted his work and gave Hoffmann rigid guidelines. Now he worked for the Reich Justice Office of the German Reich, which granted him more freedom.

Hoffmann changed almost the entire competition entry in the course of construction and undertook various study trips to Italy for further detailed planning. The correct dimensioning of the dome caused him particular difficulties. Hoffmann therefore had a model of the building made in which the dome could be adjusted in height with a crank. Only after months was he able to choose a higher dome than originally planned. Hoffmann later described the 10 years of construction as the “real school of his life”. Nonetheless, both the trade press and the client were impressed by the construction throughout the entire construction period. Kaiser Wilhelm II. , Who shortly before had publicly described Wallot's Reichstag as the “peak of bad taste”, praised the Imperial Court. It also showed Hoffmann's talent as an organizer; because all the cost and time estimates for the construction of the Reichsgericht were kept, and in some cases even undercut.

Hoffmann moved up in the hierarchy of officials. Until the completion of the building of the Imperial Court in 1895, Hoffmann was the Royal Building Officer , which was the second highest title of the German Empire. In 1906 he was awarded the title of Secret Building Councilor - the highest official title he could achieve.

Return to Berlin

After the imperial court building was inaugurated in 1896, Hoffmann returned to Berlin. With Marie Weisbach, who had just married, he moved to Potsdamer Strasse 121D in the house where Alfred Messel also lived. In 1901 the couple moved to the Tiergartenviertel on Margaretenstraße, again in close proximity to Messel, who had moved to the nearby Schellingstraße. Marie and Ludwig Hoffmann stayed here and bought the house. After the death of her husband, Marie Hoffmann moved to house number 7, which belonged to the Reichsbund des Deutschen Baugewerbes .

City planning officer in Berlin

Initial situation and choice

After the completion of the courthouse, the design of which the emperor publicly praised, Hoffmann received the offer to move to the Reich Office of the Interior as chief construction engineer and lecturer . Here he would have succeeded the late August Busse . In nominal terms, this was the highest position that a German architect could achieve in the German Empire. Hoffmann, however, refused: Despite her prominent position, this office would have consisted primarily of administrative activities and membership in commissions in architectural competitions. Hoffmann could not have built much himself, since the Reich hardly planned any new buildings. The only building that was in prospect at that time was the Reich Patent Office in the capital. At the same time, Hoffmann decided not to switch to the status of a freelance architect, which would certainly have been the better choice for him financially. But he still wanted to build buildings for the public sector.

At the same time, Ludwig Hoffmann received an oral offer from the Berlin magistrate to succeed Hermann Blankenstein as town planning officer. In 1896 he was appointed city building officer and took up office on October 1 of the same year. In the following 28 years, Hoffmann and his team shaped the city with well over 300 individual urban buildings.

The Berlin city council elected Hoffmann on February 6th with 104 out of 108 votes for a twelve-year term. The condition was that he renounced any private construction activity as well as simultaneous employment with corporations or public companies. That was a time when Berlin developed into a metropolis and the city began to feel responsible for the welfare of its population. This included schools for all residents, adequate care for the sick and the maintenance of public hygiene. Hoffmann, like his predecessor Hermann Blankenstein, tackled these tasks and thus significantly shaped the image of the city of Berlin.

Blankenstein held the office for 24 years from 1872 to 1896. After the founding of the empire in 1871, a building boom developed, which was particularly evident in the new imperial capital Berlin. The city began to develop its own building activity. Blankenstein had a wider field of activity than all of his predecessors. For example, he was responsible for the construction of numerous schools as well as the construction of hospitals, the market hall program and the construction of large slaughterhouses behind the Friedrichshain, which served to introduce compulsory slaughter and public meat inspection. Blankenstein built disinfection facilities and the first two public indoor swimming pools in Berlin in Moabit and Friedrichshain. In the last few years of Blankenstein's term in office, however, the magistrate had postponed important building projects in anticipation of the new building city council. When Hoffmann took up this office, these should be tackled immediately.

Differences to its predecessor Blankenstein

Blankenstein built a uniform brick style , the only accentuation of which was the alternation of light and dark bricks. The technical solution had priority over an ostentatious design. Contemporaries often criticized this unadorned "uniform style". The more the empire strengthened and gained in importance, the more the public wanted more representative buildings than Blankenstein built. Hoffmann should deliver this. Robertzell , then mayor of Berlin, greeted Hoffmann in office with: “But the fact that the city council elected you, the architect with such artistic design, seems to indicate that you are not reluctant to see the practical and useful once in a while a fling into the artistic is dared. "

MPs such as the Social Democrat Paul Singer praised the fact that Hoffmann has turned away from the previous barracks style . Singer and the Social Democrats in particular supported Hoffmann in his early years and stood behind the program to make the public buildings look representative. The aim was to show that the city of Berlin attaches importance to schools, for example. In his buildings, Hoffmann turned away from the previously prevailing facade design using terracotta facing bricks and designed plastered facades. On the one hand for aesthetic reasons, on the other hand because he considered them to be more durable in the long run. At the beginning of his tenure he had to assert himself against numerous opposition, which criticized the higher costs as well as the problems for the local terracotta industry, which had previously produced the facing bricks.

Upcoming construction projects

Hoffmann took over the office of town planning council when it was at its highest level. Although in terms of status it was clearly behind positions in the Reich or the State of Prussia , it still offered an area of activity for an architect that was unimaginable before and after. The state expanded its territory and the professional civil service was a central component. The construction program that lay ahead of Hoffmann was immense. Although he had 69 schools built during his term of office, the number of new buildings was not enough: At the end of his term of office, lessons were still taking place in emergency shelters or makeshift barracks because the growing Berlin needed even more schools. The rise of independent architects was only just beginning, as can be seen in the career of Hoffmann's friend Messel.

At the time of Hoffmann's inauguration, it was already clear which buildings he had to tackle with his building authority. As a condition for his employment, Hoffmann had enforced that he would build attractive large projects himself and that the city of Berlin would refrain from open tenders and competitions. It was foreseeable that Berlin would need a large new hospital as well as a new building for the Märkisches Museum . In addition, the city needed more schools, fire stations and bathing establishments. At that time Hoffmann had successfully managed the construction of the Reichsgericht, but had no practical experience with the smaller functional buildings that are typical for any local government.

By the end of his term in office, Hoffmann had carried out around 150 construction projects for the city of Berlin. No other architect built more buildings in Berlin. In addition to the 69 schools mentioned, there were four large hospitals, two psychiatric institutions, a retirement home, four swimming pools, seven official buildings, four fire stations, five depots and a museum. The buildings were concentrated in the Berlin districts of Prenzlauer Berg and Wedding, which were growing the fastest at the time .

Hoffmann as part of the bureaucracy

As a municipal employee, Hoffmann could not decide on the construction process or its implementation alone. For example, the city council had to approve every design for a building - which often increased the planning time, especially for representative buildings. The Prussian three-tier suffrage of the time also ensured a conservative-liberal majority in the city parliament. Hoffmann, who was himself a member of the magistrate , described the situation in a speech: “[I] am the architect of a building owner with 34 magistrate and 144 municipal councilors, and unfortunately only one of these 178 is mine. And even if the 177 heads - I'm now excluding my own - are the same in outstanding amiability, they are very unequal in their artistic views. "

Even if there were disputes about his construction program in the city council, especially in Hoffmann's early years, he was able to prevail over the long term. He passed the vote on a second term after twelve years in 1908 without any problems, when 77 of the 83 MPs present voted for Hoffmann. After the end of the First World War and the formation of Greater Berlin in 1920 had changed the situation in the city, and for the first time the SPD and USPD had a majority in the city administration, all city councils had to be elected. In addition to the Lord Mayor Adolf Wermuth and the city treasurer Gustav Boess , Hoffmann was the only city councilor who was confirmed in office. The now 68-year-old Hoffmann received 155 of the 158 valid votes cast.

Hoffmann solved initial problems with the building police in his favor by obtaining approval for the buildings directly from the German Kaiser Wilhelm II . Subordinate authorities no longer dared to contradict this.

In the formative part of his term of office (1898 to 1912) Hoffmann worked directly with the Lord Mayor Martin Kirschner . This member of the liberal Liberal People's Party was not only closely connected to Hoffmann personally, both men had similar ideas about the further development of Berlin and the necessary buildings. During Kirschner's tenure, the city budget doubled and he initiated the construction of numerous public buildings.

World War I, inflation period and retirement

After 1914, the First World War and its consequences, as well as the empty public coffers, prevented Hoffmann from getting his work done on the same scale as in previous years. After Greater Berlin was founded in 1920, the task in the city changed in such a way that the corresponding buildings were no longer planned by the city of Berlin and its building department: the planning and implementation of new buildings were now the responsibility of the individual administrative districts; the Berlin building department only had the overall supervision of these buildings. The focus of Hoffmann's work shifted from direct construction to administrative and coordination activities.

On April 1, 1924, Hoffmann retired at the age of almost 72. In Prussia, a pension scheme for municipal civil servants came into force, which provided for a retirement age of 65 years. Hoffmann's job description had changed so much in the years since the First World War and the Greater Berlin Act that the magistrate was discussing abolishing the position of the town planning council entirely. Finally, two years later, Hoffmann was succeeded by Martin Wagner , who was able to set similarly strong accents in the city as Hoffmann. How much times had changed can be seen in Wagner's new administration: He designed only one building himself, the Wannsee lido , but acted as the “ director of the cosmopolitan city”. Settlement construction, with which Berlin did not want to have anything to do with Hoffmann's time, had become the responsibility of the City Council. In addition, there were other areas of responsibility such as urban planning and large housing developments. Wagner initiated and coordinated, for example, the construction of the Hufeisensiedlung , the White City and the Siemensstadt housing estate . Hoffmann stayed with his wife in the house at Margaretenstrasse 18, which he had since become the owner.

Buildings as town planning officer

School buildings

Hoffmann took office at a time when Berlin's population was growing explosively. Numerous new schools were urgently needed for the many children . In terms of the crowd, these buildings formed Hoffmann's main field of activity. In addition, the free municipal school was not finally established in Prussia until the 1880s, and compulsory schooling in Prussia was extended from six to eight years in 1902. Not only did the number of children in Hoffmann's time in Berlin steadily increase, more of them also attended school longer. Since at the same time the aim was to reduce the average class size from 70 to 40 children, Berlin would have needed more classrooms even if the total number of students had remained the same. In total, Hoffmann built almost 70 school buildings throughout Berlin during his tenure. True to the demand for schools at the time, it was almost exclusively elementary schools . Total built Hoffmann 47 community Double schools for boys and girls, each with separate entrances, five simple community schools, two high schools, three Realgymnasiums , three upper secondary schools, two high schools, three high schools and six professionally oriented special schools.

When Hoffmann took a few months to familiarize himself with his office, the city councils accused him in 1899, in particular, of the fact that the school buildings were not making progress. While other German cities such as Munich were planning outstanding squares and intersections as locations for schools at that time, Hoffmann had to be content with side streets and hinterland building plots on the basis of the Hobrecht plan . Due to the large number of construction projects, Hoffmann developed, contrary to his other construction program, for the most common school type, the community double school, a standard construction plan with 56 classrooms and a physics room, plus conference rooms, school kitchen, gym, shower bath, which the children had to visit once a week for hygienic reasons, and a large assembly hall. The buildings were laid out symmetrically. Boys 'and girls' wings were alike, while communal facilities such as the gym or auditorium could be used alternately. He made adjustments if the shape of the building plot required it or if other public facilities such as baby welfare centers, control centers or public libraries were to be integrated into the building.

43. Community school , Gesundbrunnen, inner courtyard

Building of the Luisenstädtischen Gymnasium , Prenzlauer Berg

In his buildings, Hoffmann took into account both the land, which was cut differently each time, as well as the buildings in the area, so that hardly any two Hoffmann school buildings are alike. Hoffmann strived for simple, airy forms that seemed appropriate for the children as a counterpoint to the often overloaded neighboring buildings “in this outwardly fluffy and megalomaniac era”. Teachers and principals often praised the space and air that schools gave the children. A rector wrote to Hoffmann: "Since you show as a friend of the children, it will certainly also be of interest to you how beneficial your school buildings are in terms of health." The number of infectious diseases since the move was in the same period of time despite the increased number of students 39 decreased to 2.

Most of the school buildings had only short street fronts due to their location, on which Hoffmann often placed the teachers' houses. The design of their facades followed Hoffmann's other style. He particularly focused on stylistic elements from the Italian Renaissance. After he had dealt more closely with the Northern European Renaissance for the construction of the Märkisches Museum, he also began to make greater use of its stylistic devices and thus created a counterpoint to his historicist buildings in the Italian Renaissance style.

With the school buildings, Hoffmann was even more pressed to save than with his other public buildings, so that almost all of these schools were built with unadorned facades, the structure and shape of which is shaped by the window axes and the mass structure. He worked with different building heights, recessed parts of the building or risalits . Most of the school buildings were built in rapidly growing working-class neighborhoods in the north of the city, where members of the magistrate and city council did not live. Since these were also less representative buildings, they remained the least noticed part of Hoffmann's work.

Hospitals and mental institutions

Rudolf Virchow Clinic Wedding

From 1901 to 1907, under Hoffmann's planning and management, the Rudolf Virchow Hospital in Berlin-Wedding was built for 19.1 million Reichsmarks , which at the time was considered the most expensive and at the same time most modern hospital in Berlin. The construction had been decided before Hoffmann time when the city next to the hospital on Friedrichshain , the Moabit Hospital and Medical Center on Urban urgently needed new facilities for the care of the sick. The house was originally planned to offer 1,000 beds. The cost was estimated to be two and a half times that of the Imperial Court just completed by Hoffmann. The city had already acquired the property in Wedding when Hoffmann took office. Hoffmann's predecessor Blankenstein had started planning.

Hoffmann rejected Blankenstein's plans and submitted his own draft in 1897. The building complex built in the pavilion style according to Rudolf Virchow's ideas and the requirements of the municipal authorities was supposed to be a “garden city for the sick”. A total of over 50 buildings were built. Hoffmann advocated the claim that the patient should feel as welcome as possible and that leaving the home should be made easy for him. The architect wanted a "modest, yet loving construction" and a "pleasant integration of the building into friendly gardens."

The building in its extensive area looks like a park. The central backbone is an avenue. It starts from the main and entrance building, which is based on the baroque palace buildings. The patient traffic should take place over this central axis. Supply buildings have been moved out of the patient's field of vision, are located on the northern edge of the property and are accessed via their own paths. The design of the facility is influenced by the then newly built University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf , which Hoffmann, like all other new hospitals of the time, had visited in preliminary studies.

The clinic was opened in September 1906, but the last buildings were not completed until 1907. Hoffmann received positive comments from the emperor and the press was enthusiastic about the opening. The hospital was also widely noticed abroad and achieved international recognition. During Hoffmann's tenure, the Virchow-Klinikum was his internationally most famous building, with which he was most often associated. As with his other buildings, Hoffmann was mainly criticized by the liberals, who accused him of building too expensively, an accusation taken up by parts of the medical profession.

Sanatoriums Berlin-Buch / Ludwig Hoffmann Hospital

One of Hoffmann's biggest projects was the construction of the sanatoriums in Berlin-Buch . Altogether, during his tenure in Buch, an entire “hospital town” with two lung sanatoriums , an old people's and nursing home and two psychiatric clinics as well as associated administrative and supply buildings such as a residential building with a pharmacy or a post office were built. Another settlement was built after the First World War. Hoffmann built an institution cemetery and began the preparatory work for a second Berlin central cemetery.

The city of Berlin had acquired land there for the construction of clinic complexes, as there was hardly any space for other sanatoriums in the city center. Hoffmann began building a sanatorium for 150 tuberculosis sufferers from 1899 to 1905 . At the beginning of Hoffmann's tenure, tuberculosis had developed into a widespread disease that particularly affected the poorer sections of the population. The construction of the sanatorium followed the widespread sanatorium movement that then covered the entire German Empire. The other buildings used the spacious facilities, which allowed larger buildings for more patients than in the inner city of Berlin. From 1899 to 1906 the III. Municipal insane asylum, which was planned for 1,800 mentally ill people, and from 1902 to 1909 an old people's home for 1,500 residents. In 1907 Hoffmann had the IV Municipal Asylum built. The construction of the second pulmonary hospital began, but he was only able to complete it in parts.

As with previous construction projects, the city council and especially the Liberal parliamentary group criticized the construction costs. The dispute in the Buchs case was unusually fierce, so that the city council intervened directly in the architecture several times. Multiple resolutions of the assembly demanded, among other things, a "simplified facade" and later a "most possible simplification of the design of the facade". Hoffmann argued with the medical requirements that made a friendly design of the building necessary, which also included a somewhat articulated and lively facade. When building the old people's home, the city council demanded multi-storey buildings, which they considered cheaper, while Hoffmann rejected them for aesthetic and medical reasons. Ultimately, he was able to enforce his design with flat buildings, but at the price that the number of home places was reduced for cost reasons. The cause of the dispute was less the specific design by Hoffmann than generally such a large expense for a social institution that was far from the actual city.

Märkisches Museum

The Märkisches Museum goes back to the middle of the 19th century. The association founded in 1865 for the history of Berlin and the collection of the magistrate, which the city councilor Ernst Friedel had founded, were important. From 1874 there was the Museum for the City and Regional History of Berlin and the Mark Brandenburg , which initially exhibited its collections in different locations. From 1893 they were moved to the former Cölln town hall on the Spree island for a longer period of time. This was the result of the museum's wishes to have its own building from the 1880s.

The construction of its own museum showed the growing self-confidence of the city of Berlin also towards the ruler. The museum was created with a different focus than the royal museums on Museum Island . Nevertheless, the operators of the Museum Island felt attacked and expressed clear criticism of the project of a Berlin city museum. Wilhelm von Bode spoke of an "unnecessary chamber of curiosities" that did not justify a new building. At the time of Hoffmann, the city had already started a competition to build the museum and in 1893 decided on a neo-Gothic design. However, this draft encountered various difficulties and when Hoffmann took office it was finally finished. Hoffmann designed the museum himself. The city council decided on Hoffmann's completely new design on March 3, 1898. Construction work began in 1899. The construction and opening dragged on until 1908, mainly due to the conflicts with the museum management regarding interior fittings. While the operators wanted to ensure an unadorned, factual collection of the objects, Hoffmann's plan was that of a "mood museum", the visitor "should feel like in old Berlin ". Hoffmann prevailed.

In contrast to his other buildings, which were mostly based on the Renaissance and Baroque styles of Italy and southern Germany, Hoffmann planned this building to be based on the North German and Brandenburg brick Gothic from the start . In contrast to the rest of Hoffmann's work, in which he put together set pieces and details in an unorthodox way in order to do justice to the building, he wanted to remain “true to style” at the Märkisches Museum. The museum was supposed to show "on the outside the use of individual particularly interesting parts of old Brandenburg buildings from different centuries" and thus make the building itself “a museum of Brandenburg architecture”. The tour around the museum shows a chronological sequence of the architectural styles from the simple Romanesque tower to a medieval-inspired field stone base to the chapel and its high-Gothic choir, until the second part of the building takes up motifs from the brick renaissance . Opposite the building is the state insurance company designed by Alfred Messel, which picks up on the chronological thread and continues to weave it with its baroque facade. The Märkisches Museum is also the only one of Hoffmann's larger buildings that shows a brick facade.

True to his commitment to tailor buildings precisely to their purpose and to treat them individually, Hoffmann carefully planned the interiors with reference to the collections that were to be exhibited there. He asked the museum management to measure the large exhibits himself so that he could adapt the building to them. According to Hoffmann's concept, prehistory and early history were to be exhibited in the basement, the natural history collection on the first floor and cultural-historical pieces on the top floor. Below that, the chapel room was intended for pieces on church affairs. However, this also meant that the building made any change in use, any significant change in the collection or a change in the exhibition concept more difficult, as it was not prepared for this. During the construction of the museum, there were disputes between Hoffmann and the museum management about the implementation of the construction planning. In retrospect, it was precisely this inflexibility that has been criticized almost consistently in construction since the 1920s. From 1925 onwards, the museum director Walter Stengel made this particularly pointed and formative .

Swimming pools

The implementation of the program for the construction of public swimming pools in Berlin , which was decided in 1895 before Hoffmann took office, also fell during Hoffmann's term of office . From 1891 to 1895, Hermann Blankenstein had two simple baths, and thus the first communal swimming pools in Berlin, in Moabit and in the Stralau district . But that was also controversial: up until the 19th century, the city limited itself to building pure hygiene facilities with only showers and bathtubs. Compared to other major German cities, Berlin began building swimming pools late. This was encouraged by the high number of visitors in the previous buildings, but always controversial in the city because of the costs. The additional construction of swimming pools in closed rooms was also criticized because of the resistance of the operators of private swimming pools. Some city councilors spoke of palaces for bathing establishments . A part of the Liberals did not follow Hoffmann and the city administration, while the Social Democrats spoke out in favor of building these public baths. On these points, Hoffmann only implemented the program that was decided before he took office. The fact that the bathrooms were more complex than the previous pure bath tubs was the trend of the time, since around 1900 bathing establishments with real swimming pools were built all over Germany.

Hoffmann's design for the Stadtbad Kreuzberg in Baerwaldstrasse was one of the first tasks that the new town planning council tackled. As with many early buildings, it was based on the example of the Italian Renaissance. At first glance, the bathroom looks like an Italian palazzo. However, Hoffmann consciously uses stylistic devices that would never have existed in this one: the frieze of hatches between the ground floor and main floor, behind which the baths were located, would have been inconceivable in a palazzo of the time. The hard transition from the rustication , the protruding natural stones, in the lower part of the building to the smooth facade in the upper part was unusual . While all the building details were found in historical models, their arrangement and orientation towards the rest of the building was more original and original Hoffmann. Just like in the second building, Stadtbad Prenzlauer Berg , the baths were built in a building complex with a school, whereby the bath got the street front and the school, like other Hoffmann schools, was mainly located in the rear part of the property.

The Stadtbad Dennewitzstrasse, then in Kreuzberg, was built under his leadership. This was hidden near the Gleisdreieck in the hinterland and on the property and was visually superimposed by the railway systems, so that its facade was hardly designed. Hoffmann's last bath, the Stadtbad Wedding , was built on a larger property than the previous baths, so there was more space for the building and was the first bath in Berlin to have two swimming pools - one for men and one for women. The ongoing fundamental criticism of the finished swimming pools prevented further new swimming pools being built before the First World War. Hoffmann designed the bathrooms differently. In the case of the Baerwaldbad, as in the case of the imperial court or the town hall, it was based on the Italian Renaissance.

Hoffmann's last project that he had planned himself was the Wannsee lido . It wasn't completed until after he retired. His successor Martin Wagner replaced the buildings there less than ten years later with a larger and more modern facility.

Townhouse

The Red City Hall was not completed until 1869. In view of the growing city and the growing tasks of the administration, it soon turned out to be too small. When Hoffmann took office, the decision for another administrative building had already been taken. With the town hall , the magistrate wanted a building that, for practical reasons, should have a central inner city location and be larger than the Red Town Hall, but without competing with it in the cityscape.

Hoffmann designed a building for 1000 civil servants and with two small meeting rooms. Although the building was not intended to serve as a representative building, Hoffmann planned a tower from the start to highlight the building in the area. In response to criticism from the city council of this tower, Hoffmann referred to the tradition of city administration houses, which were made visible by towers. In contrast to the initial requirements, Hoffmann succeeded in establishing a centrally located, large and representative hall inside the building.

The construction was approved in 1901 and completed in 1911. Hoffmann designed a building on an irregularly cut plot of land that simulates a great symmetry that neither the plot nor the building have. Hoffmann strived for a facade that expressed "strength and calm" and chose shell limestone as the building material , which filled a facade system influenced by the Renaissance. He was based on Palladio's Palazzo Thiene and the Palazzo del Tè in Mantua.

In fact, after completion, this hybrid position often led to criticism. On the one hand, it was an office building that had hardly any representative rooms inside and was only used for day-to-day administration. In fact, however, it was larger, with a more valuable-looking facade and more elaborately designed than the actual town hall. Contemporaries, however, held Hoffmann less responsible for this than his clients, who could not clearly decide what kind of building they wanted.

More buildings

Hoffmann was able to realize some of the most famous buildings in the city with the help of art deputation . After he was repeatedly exposed to critical inquiries from city councilors in his everyday life, who found his buildings too expensive and wanted simpler buildings, the means of the art deputation were intended exclusively to promote culture and art in Berlin. From this fund, for example, the decorations on individual school buildings , in the children's asylum or the wedding room in the Fischerinsel registry office were paid for. Hoffmann also used these funds to create public fountains such as the Herkulesbrunnen on Lützowplatz . The most elaborate work that took up a large part of the budget of the art deputation was the fairy tale fountain in Volkspark Friedrichshain .

The Märchenbrunnen was a special building in Hoffmann's work. It was planned to decorate the entrance to the Volkspark even before Hoffmann took office. To design this jewelry especially for children and to use the motif of fairy tales came from Hoffmann's ideas. The Volkspark Friedrichshain was the only green space in the densely built-up working-class district of Friedrichshain. It was used extensively by the workers' children. To implement this decoration of the park entrance not as representative ostentatious architecture, but rather through fairy tale characters, was an absolute novelty for Berlin. The building became one of the most politically controversial Hoffmanns. Kaiser Wilhelm II endorsed the idea, but rejected the specific design and had this communicated in 1901 by the building police, who rejected the design for artistic reasons. The magistrate of the city of Berlin, however, insisted that this was a purely urban matter in which no imperial approval was required. The case boiled up in the press and the city council.

Hoffmann, however, was able to understand many of the Emperor's criticisms and was not even satisfied with the design. Both found the figures too high for children. The originally planned three-part system did not result in any internal cohesion. The positions converged, also because Hoffmann and the Emperor had a comparatively good and close relationship with one another since the building of the Imperial Court. Nevertheless, it was not until 1913 that the fountain was actually built. In the end, the fountain came back into the press, but this time as the slowest building in the city. The fountain uses the gradient that the Volkspark has at this point. Hoffmann finally created a large fountain in which the water flows down from the highest point in four terraces. The highest point of the cascade is bounded by an arcade architecture . The well-known characters from Grimm's fairy tales are at children's height on the edge of the largest pool. In the fountain itself there are figures of frogs. Clear echoes of the water features of the Italian early baroque can be seen throughout the design of the complex. In particular, he oriented himself to the water theater in the Villa Mondragone .

At the beginning of his tenure, Hoffmann built several bridges in cooperation with the city's civil engineering department. As a result, the building department, which Hoffmann was in charge of, and the civil engineering department were separated. After Friedrich Krause became head of the Berlin Civil Engineering Office in 1897, it quickly became apparent that the ideas of the two heads of office were not compatible. After Krause took office, Hoffmann only designed the Lessing Bridge in Moabit and the Adalbert Bridge in Mitte. During this building there was a final rift between Hoffmann and Krause. In the last 20 years of his tenure, Hoffmann was only able to build the Inselbrücke in Berlin-Mitte. Krause awarded other contracts for bridge construction almost exclusively to independent architects. In his memoirs, published later, Hoffmann regretted the strict separation between civil engineering and civil engineering.

Further work as town planning officer

Local statute for Berlin

The organizational and personal circumstances of the Berlin administration at the time did not allow Hoffmann to extend his activity to urban planning. He limited himself to individual buildings, while street alignment, civil engineering and the distribution of public buildings remained outside of his jurisdiction. He saw the announcement of a public competition for development plans for Greater Berlin in 1908/1909 as an outbreak of this restriction. Hoffmann was also on the jury for this competition, which had no practical impact. The First World War, which began in 1914, then made other questions appear more urgent.

One of Hoffmann's special tasks was to maintain the local status to protect the cityscape. The rapidly growing cities of the time gave rise to the first statutes to protect the cityscape; In 1907 the state of Prussia passed a law against the defacing of localities , which the Berlin administration joined. This ordinance subsequently protected the important parts of the urban area such as Unter den Linden or Wilhelmstrasse from inappropriately redesigning and reduced advertising there. The new law also protected three Hoffmann buildings, the Rudolf Virchow Hospital , the Märkisches Museum and the town hall. Hoffmann was the chairman of an expert council that was supposed to decide in cases of doubt whether a building was appropriate. After Greater Berlin had been formed with the surrounding communities in 1920 , Hoffmann led efforts to create a common status for historic Berlin and the newly added surrounding communities. The local statute for the protection of the city of Berlin against defacement came into force in 1923.

Crown Prince Silver

Hoffmann had developed a special reputation for representative design in the city: He became the head of a commission to supervise the work of twelve art and silversmiths , which was given as a wedding present for Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm and Cecilie zu Mecklenburg on June 5, 1905 made intended table silver . The ensemble, a gift decided by the Prussian Association of Cities in 1905, comprised 2,700 individual parts and was designed for 50 people.

Manufacture of festive decorations

Hoffmann was representative in other respects, as he was also responsible for the production of special festival decorations in the city. He made a total of eleven festival decorations here. The most elaborate one was when Franz Joseph I visited the German Emperor in 1900. Hoffmann had a triumphal arch built on Pariser Platz and ensured a continuous design from Pariser Platz to the Berlin City Palace.

As a jury member

Hoffmann soon gained some influence on the entire German building industry, for example as a jury member in many architecture competitions. He supported the design by Hugo Lederer and German Bestelmeyer for the memorial for the fallen of Berlin University in 1920 (inauguration 1926).

Late buildings and designs

Completion of the Pergamon Museum

Despite opposing careers, Messel as a freelance architect and Hoffmann as a construction clerk, they kept building together. When Empress Auguste Viktoria insisted on commissioning Hoffmann as the architect for the Kaiserin-Auguste-Viktoria-Haus to combat infant mortality , he felt professionally overloaded at the time. He brought Alfred Messel in. The Empress insisted on Hoffmann's participation and so they both built the hospital in Berlin-Charlottenburg together. After Messel became seriously ill in the early 1900s, Hoffmann continued his building projects and supervised them, for example the construction of the Lettehaus in Berlin-Schöneberg, the Palais Cohn-Oppenheim in Dessau and the Hessian State Museum in Hoffmann's and Messel's hometown Darmstadt.

As early as 1908, after Messel's stroke, Hoffmann had become an important point of contact for Wilhelm von Bode and the site management, and after Messel's early death in 1909, he took over the building at the request of the Emperor and on behalf of the Ministry of Culture. With von Bode and Hoffmann, there were now two strong personalities who both enjoyed the Kaiser's favor and were politically well connected. However, the completion of the building turned into a permanent conflict between Hoffmann and von Bode. Until his own death in 1932, Hoffmann carried out further alterations and additions to the Pergamon Museum .

Design for a New Royal Opera House

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Prussian State and Wilhelm II favored the construction of a new opera house to replace the Unter den Linden State Opera . This seemed too small for the time, and there were concerns about its fire safety. The construction of the New Royal Opera House in Berlin developed into a story of spectacular failures, which journalist Paul Westheim described as the “grotesquest architectural comedy of all time”. Hoffmann was asked early on whether he wanted to work here. He saw his task, however, in the construction of social and not representative buildings. In addition, he had not had good experiences with the responsible authorities when he finished building the Pergamon Museum with them after Messel's death.

Only after three failed architecture competitions, when Kaiser Wilhelm II and Berlin Mayor Adolf Wermuth both personally valued a design by Hoffmann in 1913, did he start working on it. This last request came at a time when Hoffmann's large buildings in Berlin had all been completed and he was only actively involved in the Pergamon Museum and the routine program of school buildings. The final decision in favor of Hoffmann as master builder of the opera was made in May 1913.

In accordance with the requirements, Hoffmann designed the building as a court and state theater and dealt intensively with the court buildings that had been created in the first half of the 19th century. In doing so, he designed a compact structure that is usual for classicism. Hoffmann rejected developments of the late 19th century such as sweeping side wings (as in the Semperoper or the Vienna Burgtheater ) or the prominent roof structure of the Paris Opera . Hoffmann's plans were announced in January 1914. Sharp criticism came from the Free Architects, who took it particularly badly that, after three competitions, a municipal building official was supposed to carry out the construction. The commission responsible finally approved the funds for the construction in May 1914. The New Royal Opera House was never built. The First World War prevented the start of construction. The Weimar Republic set different priorities in planning than royal opera houses.

style

Hoffmann was influenced by his travels to Italy and oriented himself towards the architecture of the Italian Renaissance. In particular , he repeatedly highlights Andrea Palladio and Michele Sanmicheli as exemplary - whereby Hoffmann does not address individual formal elements, but rather the overall well thought-out effect of the building and its relationship to the environment. Hoffmann meticulously prepared his study trips to Italy, made sketches on site and based his buildings in Germany on them. Hoffmann read both the architectural and the art-historical works about this period. He was particularly influenced by Jacob Burckhardt , who triggered this enthusiasm for Italy in Hoffmann throughout his life. Hoffmann placed particular emphasis on the artistic interplay of the elements and opposed only adopting individual design elements.

In addition, he emphasized that a building should adapt to its surroundings, be individually designed and have a well thought-out floor plan. Hoffmann favored careful construction and thus implicitly turned against architecture, which pursued a certain style regardless of purpose and surroundings and always resembled itself. In private conversations, Hoffmann characterized many buildings of his time as overloaded, senseless and thoughtless architecture that does not relate to its spatial surroundings. Hoffmann's buildings often appear eclectic at first glance . This is mainly due to the attempted adaptation to the purpose and environment. Hoffmann tried to find a middle way between the exuberant historicism of the time and the simultaneously emerging industrial mass construction, the first effects of which began to show in the 19th century. He observed that the two were often connected, since the most monotonous and most simply built houses were often decorated with the most overloaded jewelry.

He tried to give the buildings an individuality in harmony with their surroundings, which nevertheless did not appear overloaded. Hoffmann moved with the times when it came to the tasks he had chosen, building schools and other public buildings, which at the time seemed necessary in the course of industrialization and urban growth. Stylistically, however, he was attached to tradition. His model was the old Berlin Schinkel and Lennés . Hoffmann stood between the ages: in his building projects and their friendly, bright design for the often poor users, he prepared the emerging metropolis of Berlin for the future. His style and his way of working were often still rooted in the 19th century and were often enough seen as a statement against modernity. He turned against the industrially manufactured construction, relied on artisanal construction, which was close to a moderate historicism and homeland style. He spoke out against the modern “in its external form”, but tried to give children, the sick and others “friendly impressions” or “a home away from home” with his buildings, which they needed in the modern era that was breaking in around them. When he took office, he described his program as "putting me in the soul of the person who will buy the building and asking me whether the pupil, the fireman, the judge or the sufferer can feel comfortable in such walls."

aftermath

After Hoffmann was able to count on the backing and support of the Kaiser, the liberal Berlin mayors and the Social Democrats in the city council, this changed quickly after the First World War and his resignation from office in 1924. The first strong criticism was already evident in the draft for the New royal opera house by the independent architects and the construction of the Pergamon Museum, which led Hoffmann into an ongoing conflict with Wilhelm von Bode . But this was not yet a fundamental criticism of Hoffmann's style. When he left office, the evaluation of his work in the press was largely positive. The restriction that he was “a child of his time” implies that another time would come now.

The criticism of Hoffmann escalated because of his work in the commission to uphold the local statute. It was first violently ignited by Hoffmann's rejection of Max Taut's printing house. Here, the Association of German Architects, led by Erich Mendelsohn and Hans Poelzig, wrote a statement that was directed against “unilateral and patronizing decisions by the authorities”. This was generally understood as an attack on Hoffmann and was meant to be. In the further argument, Hoffmann was attacked personally. From the group of architects who came into conflict with Hoffmann in particular, the anti-Hoffmann architectural association Der Ring later formed .

The criticism was increasingly severe, also with Hoffmann's earlier work. In Das Kunstblatt, Paul Westheim attested an architectural weightlessness to his buildings, which he interpreted as cultivated eclecticism and which identified him as a mediocre architect of temperate progress. Adolf Behne judged even more harshly in the Weltbühne , who reviled the buildings as drawing facades while neglecting reality. As in the conflict with the town planning council, the younger, up-and-coming architects of the modern age defended themselves against Hoffmann, who was still influential in the town and who had become one of the last representatives of the classic building officials. There is only a good relationship with Bruno Taut ; the other architects of the new generation wanted to break away from Hoffmann and his influence as far as possible.

Hoffmann died in 1932, shortly after his 80th birthday, largely withdrawn from the public. The extent to which he has already disappeared from memory is shown by the fact that only eight years after his resignation from the office of town planning council hardly any necrologists appeared in the newspapers. Even Adolf Behne stated that the Berlin press treated the death of Ludwig Hoffmann with a striking indifference, who built more in this city than all Schlüter , Eosander , Knobelsdorff , Gontard , Langhans and Schinkel put together.

In works that dealt with him, the perspective of the conflicts of the 1920s often shone through, and less of the master builder of the 1900s, in which Hoffmann's most formative and style-typical buildings were created. In the public consciousness, it was the prestigious buildings in prominent positions in the city such as the town hall or the Märkisches Museum, not the much more typical social buildings such as hospitals, schools or swimming pools. The work of Ludwig Hoffmann - like the entire architecture of Historicism - was widely criticized for a long time.

A small renaissance did not begin until later. 1956 declared Ludwig Mies van der Rohe , itself a leading member of the Association of Ring: "Yes, yes, of Hoffmann, which we have all done wrong!" . Julius Posener made his first efforts to bring Hoffmann back into the public eye in the 1970s. He described Hoffmann as the “most mature and richest expression of the official endeavors of the time.” In 1977, on the initiative of Posener, the Berlin Academy of the Arts organized a ceremony to mark Hoffmann's 125th birthday. In 1987, the West Berlin State Archives organized the first exhibition on Hoffmann under the title Rediscovery of an Architect .

Hoffmann came more into the public eye after the political change . The Imperial Court building was used as a courthouse again for the first time since World War II in the 1990s. In view of the centenary of its inauguration in 1995/1996, an exhibition was held. The Märkisches Museum was rebuilt and renovated in 1999 and has been better perceived by the public since then. In view of Hoffmann's 150th birthday and 70th anniversary of his death in 2002, the Architecture and Engineers' Association and the Berlin State Archives organized the Ludwig Hoffmann exhibition . City Planning Council of the municipal Berlin. 1896-1924 . The Academy of the Arts closed in the same year with an exhibition in the Künstlerhof Buch Stadtbaurat Ludwig Hoffmann, 1852–1952. Grow in Berlin and Buch . In Berlin to this day (as of 2019) only the bridge shown above over the Westhafen Canal , the Ludwig-Hoffmann-Grundschule in Berlin-Friedrichshain and the Ludwig-Hoffmann-Quartier (formerly part of the Buch Clinic) in Berlin-Buch bears his name. In view of his fame as a star architect, which Hoffmann had during his active time, there are hardly any memories or honors for Hoffmann in the city compared to other important architects of the time.

Ludwig Hoffmann was buried in the old cemetery in Darmstadt (grave site: I Wall 27). His estate has been in the Berlin State Archives since 1989.

Awards

Honors were initially limited to the time during and directly after Hoffmann's work. In 1901 he received a small gold medal at the Great Berlin Art Exhibition and in 1909 a large gold medal . In 1906 he received the title of Privy Building Councilor . Together with his close friend Alfred Messel, he received an honorary doctorate from the Technical University of Darmstadt in 1906 . In the same year the Prussian Academy of the Arts appointed him as a full member. In 1913 he was elected a member of the Knight of the Order Pour le Mérite . Hoffmann received numerous Prussian and German medals. In 1917 he received another honorary doctorate from the Vienna University of Technology . When Ludwig Hoffmann retired in 1924, the city of Berlin made him an honorary citizen . On July 30, 1932, the city of Darmstadt followed with an honorary citizenship.

A street in Leipzig- Sellerhausen is named after him.

The Ludwig-Hoffmann-Grundschule he built on Lasdehner Strasse in Berlin-Friedrichshain , the Ludwig-Hoffmann-Quartier on the hospital grounds in Berlin-Buch and the Ludwig-Hoffmann-Brücke in Berlin-Moabit bear his name in the 21st century .

Work overview

Buildings (selection)

Hoffmann was responsible for around 150 public construction projects during his time as a building city councilor. 69 of them were schools alone. In the Berlin districts of Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg, Mitte and Pankow there are still around 100 Hoffmann buildings, most of which are listed .

- 1887–1895: Imperial Court Building in Leipzig (together with Peter Dybwad )

- 1897–1901: Alsenbrücke in Berlin-Moabit ( demolished for the expansion of the Humboldthafen )

- 1898–1901: Volksbadeanstalt Baerwaldstrasse in Berlin-Kreuzberg

- 1898–1900: Community dual school Wilmsstraße with public library, first school he completed.

- 1898–1901: Dennewitzstrasse bathing establishment (destroyed)

- 1899–1901: Residential building Dennewitzstraße (formerly with entrance to the bathing establishment)

- 1899–1907: Rudolf Virchow Hospital in Berlin-Wedding

- 1899–1902: Volksbadeanstalt Oderberger Strasse in Berlin-Prenzlauer Berg

- 1900-1907: III. Urban madhouse

- 1901–1907: Märkisches Museum in Berlin, Am Köllnischen Park 5

- 1902–1911: Old town house

- 1902: Fire station , Berlin-Kreuzberg

- 1904–1907: Administration building and two nursing homes for the Moabit hospital

- 1905–1908: Volksbadeanstalt Richtstrasse

- 1905–1909: Old people home book

- 1907–1908: 239th and 296th Community School Christburger Strasse in Berlin-Prenzlauer Berg

- 1907–1909: Administration building for the municipal gas works in Berlin-Mitte (today the seat of the higher commercial school BEST- Sabel )

- 1907–1909: Kaiserin-Auguste-Viktoria-Haus , Berlin-Charlottenburg , Heubnerweg 6/10 (today ESCP Europe Business School Berlin )

- 1907–1913: Märchenbrunnen in Volkspark Friedrichshain

- 1908–1910: Zeppelinplatz school complex : Community dual technical secondary school, XIV. Realschule

- 1908–1910: Albrechtstrasse official building , today the Ukrainian embassy in Germany

- 1909–1910: Schillerpark fire station

- 1909–1914: IV Municipal Madhouse

- 1909–1914: Higher Web School Berlin, Warschauer Platz (moved in 1919 as Higher Technical School for Textile and Clothing Industry )

- 1910–1930: Execution of the Pergamon Museum in Berlin based on a design by Alfred Messel . The architect Wilhelm Wille was also involved .

- 1911: Paul Singer's tomb

- 1911–1915: Building trade school Kurfürstenstrasse

- 1912–1913: Inselbrücke in Berlin-Mitte

- 1912–1915: Stockholmer Strasse fire station

- 1924–1925: Wannsee lido

In the architecture museum of the Technical University of Berlin there are more than 1100 representations (status 11/2016) of Ludwig Hoffmann.

A fairly complete list of Ludwig Hoffmann's buildings can be found at www.bildindex.de (art and architecture).

drafts

In 1884 a joint competition design by Hoffmann and Emanuel Heimann for the development of the Berlin Museum Island was purchased.

Fonts

- The Imperial Court Building in Leipzig. Overall views and details based on the original drawings of the facades and interiors, as well as nature photographs of the most remarkable parts of this building, which was erected between 1887 and 1895. 2 volumes, Verlag Bruno Hessling, Berlin 1898.

- Hoffmann took up the idea and form of the publication on the Leipzig courthouse during his time as Berlin City Planning Director and published the series Neubauten der Stadt Berlin . Eleven volumes were published between 1902 and 1912, covering almost all of Hoffmann's buildings up to 1912. In addition to smaller sections of text, the volumes mainly contained picture panels. The volumes were published by Verlag Bruno Hessling until 1904, and from 1904 by Verlag Ernst Wassmuth.

- New buildings in the city of Berlin. Overall views and details based on the original drawings of the facades and interiors, as well as nature photographs of the most remarkable parts of the urban buildings built in Berlin since 1897. Volumes 1–11, Bruno Hessling, Berlin / New York 1902–1912.

- The GDR Bauakademie published an extended reprint of the font by Ludwig Hoffmann Neubauten der Stadt Berlin , Bruno Hessling, Berlin 1902:

- Architecture by Ludwig Hoffmann (1852-1932) in Berlin. Reprint with a foreword by the President of the GDR Building Academy, Hans Fritsche . Introduction: Hans-Joachim Kadatz, editor: Building Academy of the German Democratic Republic, Verlag Bauinformation, Berlin 1987.

- Hoffmann left a record of his memoirs. With the permission of his widow, an excerpt from the 241-page manuscript was published in 1960:

- Islands of taste in Berlin. From the memoirs of the Berlin City Planning Council. In: Landesgeschichtliche Vereinigung für die Mark Brandenburg (Ed.): Yearbook for Brandenburg State History ( ISSN 0447-2683 ), Volume 11 (1960), pp. 14–46; edoc.hu-berlin.de (PDF; 20 MB)

- The full text, with the exception of a few family passages, was published by Wolfgang Schächen with the support of Ludwig Hoffmann's daughter Annamarie Mommsen (1903–2000) in 1983. A second edition appeared in 1996:

- Life memories of an architect. Edited and edited from the estate by Wolfgang Schächen. With a foreword by Julius Posener . The buildings and art monuments of Berlin. Supplement 10, Gebr. Mann Verlag Berlin 1983, ISBN 3-7861-1388-2 .

- Further texts by Hoffman:

- Architectural effects . In Wasmuth's monthly magazine for architecture 1, 1914, pp. 3–13.

- A look to Alt-Berlin, In: Wasmuths MONTHS for Baukunst 2, 1915/16, pp. 261–307.

- Higher weaving school on Warschauer Platz. In: Wasmuthsmonthshefte für Baukunst 2, 1915/16, pp. 481–485.

- The convalescent home in Buch. In: Wasmuthsmonthshefte für Baukunst 6, 1921, pp. 327–374.

- In 1981, Julius Posener recorded Hoffmann's celebratory speech at the Schinkel Festival in the Architects' Association in Berlin on March 13, 1898 in his volume Festreden, Schinkel in honor of Schinkel .

- About the study and working methods of the masters of the Italian Renaissance. In: Festreden, Schinkel in honor, 1846–1980, selected and introduced by Julius Posener, published by the Architects and Engineers Association of Berlin, Berlin 1981, pp. 236–248.

literature

in alphabetical order by authors / editors

- Building Academy of the German Democratic Republic (ed.): Architecture by Ludwig Hoffmann (1852–1932) in Berlin. Building information GDR, Berlin 1987.

- Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann: Building for Berlin 1896-1924 . Ernst Wasmuth, Tübingen 2004, ISBN 3-8030-0629-5 .

- Thomas G. Dorsch: The imperial court building in Leipzig. Demand and reality of a state architecture. Frankfurt am Main 1999, ISBN 3-631-35060-0 . (also dissertation, University of Marburg, 1998.)

- Jan Feustel : Wilhelmine smile. Buildings by Hoffmann and Messel in the Friedrichshain district. Heimatmuseum Berlin-Friedrichshain, Berlin 1994.

- Hans-Jürgen Mende , Kurt Wernicke (ed.): Berlin district lexicon Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg. Haude & Spener, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-7759-0474-3 .

- Max Osborn : Ludwig Hoffmann. In: Velhagen & Klasing's MONTHS , Volume 27, 1912/1913, Volume I, p. 189 ff. (With numerous illustrations)

- HJ Reichhardt, Wolfgang Schächen : Ludwig Hoffmann in Berlin. Transit, Berlin 1987.

- Hans Reuther : Hoffmann, Ludwig. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 9, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1972, ISBN 3-428-00190-7 , p. 397 ( digitized version ).

- Volker Viergutz: We wouldn't have dreamed of that either - remarks on the friendship between Ludwig Hoffmann and Alfred Messel . In: Jürgen Wetzel (Ed.): Berlin in past and present. Yearbook of the Berlin State Archives 2001 . Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin 2001, pp. 73–124.

- Phillip Wagner: Demands and Reality of Ludwig Hoffmann's Municipal Architecture. Berlin 2009. (at the same time academic term paper within the First State Examination for the Office of the Academic Council, Humboldt University Berlin 2008.) ( kobv.de )

- Paul Westheim : Ludwig Hoffmann. In: Illustrated Universum-Jahrbuch 1912. Reclam, Leipzig 1912, pp. 384–389.

- Kathrin Wittschieben-Kück: The use of the column arrangements in Ludwig Hoffmann (1852-1932) . In: INSITU 2020/1, pp. 119–130.

Web links

- Literature by and about Ludwig Hoffmann in the catalog of the German National Library

- City Planning Officer Dr. techn. hc Ludwig (Ernst) (Emil) Hoffmann. In: arch INFORM .

- Projects, sketches and construction plans by Ludwig Hoffmann ( Architecture Museum of the Technical University of Berlin )

- Biography, Hoffmann's buildings in Berlin via archive.org [1]

Notes and individual references

- ^ A b Hans J. Reichardt: Walk through the exhibition . In: Reichardt, Schächen (Ed.): Ludwig Hoffmann in Berlin , p. 45.

- ^ Reichardt, Schächen (Ed.): Ludwig Hoffmann in Berlin , p. 6.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann… , p. 10.

- ↑ Volker Viergutz: We would have ... , p. 76.

- ^ A b Hans J. Reichardt: Walk through the exhibition . In: Reichardt, Schächen (Ed.): Ludwig Hoffmann in Berlin , p. 46.

- ↑ a b c Volker Viergutz: We would have ... , p. 74.

- ↑ a b Volker Viergutz: We would have ... p. 75.

- ^ Wolfgang Schächte : Ludwig Hoffmann between historicism and modernity . In: Reichardt, Schächen (Ed.): Ludwig Hoffmann in Berlin , p. 9.

- ↑ The Black Ring. Membership directory. Darmstadt 1930, p. 32.

- ↑ Volker Viergutz: We would have ... , p. 77.

- ^ Directory of the award-winning competition designs for the Schinkel Prize. In: Wochenschrift des Architekten-Verein zu Berlin , 6th year 1911, No. 10 (from March 11, 1911), p. 54, accessed on January 11, 2020.

- ↑ Volker Viergutz: We would have ... p. 80.

- ↑ a b c d e f Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 11.

- ↑ a b c d Wolfgang Schächen : Ludwig Hoffmann between historicism and modernity . In: Reichardt, Schächen (ed.): Ludwig Hoffmann in Berlin p. 13.

- ^ Hans J. Reichardt: Walk through the exhibition . In: Reichardt, Schächen (Ed.): Ludwig Hoffmann in Berlin , pp. 51–52.

- ↑ Potsdamer Str. 121d> Hoffmann, L., Kgl. Baurath and Messel, A., Prof. In: Address book for Berlin and its suburbs , 1900, III, p. 482.

- ↑ Margartenstr. 18> Hoffmann, L., Royal Building Councilor . In: Berliner Adreßbuch , 1905, III, p. 490.

- ^ Margaretenstrasse 18> Hoffmann, M .; Owner . In: Berliner Adreßbuch , 1935, II, p. 534 (The name is misspelled: Instead of H u ffmann, M., it has to be correctly called H o ffmann).

- ↑ a b Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 25.

- ↑ a b c Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 26.

- ↑ Ludwig Hoffmann. bverwg.de, accessed on November 9, 2016 .

- ↑ a b Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 8.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 23.

- ^ Hans J. Reichardt: Walk through the exhibition . In: Reichardt, Schächen (ed.): Ludwig Hoffmann in Berlin , p. 54.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 24.

- ↑ a b c Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 38.

- ↑ a b Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 40.

- ↑ a b Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 32.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 27.

- ↑ a b c Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 35.

- ↑ a b c Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 41.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 49.

- ↑ a b Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 34.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 36.

- ↑ a b Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann… , 50.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , pp. 55–57.

- ↑ Hoffmann, Ludwig . In: Berliner Adreßbuch , 1927, I, p. 1327 ((E) means owner).

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 116.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 39.

- ↑ a b c Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 117.

- ^ Hans J. Reichardt: Walk through the exhibition . In: Reichardt, Schächen (Ed.): Ludwig Hoffmann in Berlin , p. 79.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 119.

- ^ Hans J. Reichardt: Walk through the exhibition . In: Reichardt, Schächen (Ed.): Ludwig Hoffmann in Berlin , p. 80.

- ↑ a b Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 67.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 60.

- ^ Bernhard Meyer: A garden city for the sick. In 1906 the Virchow Hospital was opened . In: Berlin monthly magazine ( Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein ) . Issue 4, 2000, ISSN 0944-5560 , p. 118-123 ( luise-berlin.de ).

- ↑ a b Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 70

- ↑ a b Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 74.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 76.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 77.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 84.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 85.

- ↑ a b c d e f Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann… , pp. 86–87.

- ^ Wolfgang Schächte : Ludwig Hoffmann between historicism and modernity . In: Reichhardt, Schächen (Ed.): Ludwig Hoffmann in Berlin , p. 26.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 90.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 101.

- ↑ a b Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 124.

- ^ Wolfgang Schächte : Ludwig Hoffmann between historicism and modernity . In: Reichhardt, Schächen (Ed.): Ludwig Hoffmann in Berlin , p. 19.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 125.

- ↑ a b c Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann… , pp. 104-105.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 106.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 114.

- ↑ a b Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 44.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 137.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 138.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 139.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 141.

- ^ Wolfgang Schächte : Ludwig Hoffmann between historicism and modernity . In: Reichardt, Schächen (Ed.): Ludwig Hoffmann in Berlin , p. 33.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 43.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 46.

- ^ Christian Saehrendt: Anti-Semitism at the Berlin Friedrich Wilhelms University. Zukunft-bendet-erinnerung.de, January 19, 2010, accessed on November 9, 2016 .

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 134.

- ↑ Volker Viergutz: We would have ... p. 85.

- ↑ Volker Viergutz: We would have ... p. 107.

- ↑ a b Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 157.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 167.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 175.

- ↑ a b c Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 61.

- ↑ a b Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 62.

- ↑ a b Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann… , pp. 64–65.

- ↑ a b Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 179.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 179.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 195.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 196.

- ^ Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 198.

- ↑ Volker Viergutz: We would have ... , p. 73.

- ^ A b Hans J. Reichhardt: Foreword . In: Reichardt, Schächen (ed.): Ludwig Hoffmann in Berlin , p. 7.

- ↑ a b Dörte Döhl: Ludwig Hoffmann ... , p. 9.

- ^ Ludwig-Hoffmann-Quartier

- ↑ One of the facilities was called Ludwig-Hoffmann-Hospital 1933–1950 and Ludwig-Hoffmann-Hospital from 1950–1963 (a bus stop of the same name still exists), see Berlin book - hospital tradition - old people home - history of the site .

- ^ Works by Hoffmann in the Architekturmuseum der TU Berlin

- ↑ Image index of art & architecture. In: bildindex.de. Retrieved March 6, 2019 .

- ^ Centralblatt der Bauverwaltung , Volume 4, 1884, No. 15 (from April 12, 1884), p. 143 ( zlb.de ).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hoffmann, Ludwig |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Hoffmann, Ludwig Ernst Emil (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German architect and city planner in Berlin |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 30, 1852 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Darmstadt |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 11, 1932 |

| Place of death | Berlin |