Old town house (Berlin)

| Old town house | |

|---|---|

The old town house in 2016 |

|

| Data | |

| place | Berlin center |

| architect | Ludwig Hoffmann |

| Client |

Magistrate of Berlin (later Magistrate of Greater Berlin) |

| Construction year | From 1902 |

| height | Tower 80 m |

| Floor space | 9990 m² |

| Coordinates | 52 ° 30 '59 " N , 13 ° 24' 39" E |

| particularities | |

| City coat of arms removed from the gable around 1976 | |

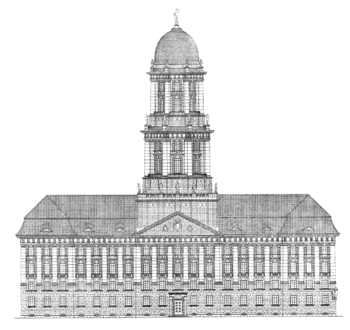

The Old Town House is the name of a representative administration building in Berlin district of Mitte , which the then city government magistrate from Berlin to relieve the Red Town Hall in the years 1902-1911, designed by the City Commissioner of City Planning Hoffmann Ludwig for seven million Goldmark had built (€ 40 million) . It is located on Molkenmarkt between Jüden , Kloster , Parochial and Stralauer Strasse and was initially called the New Town House after its completion in 1911 .

After the Second World War , the town house building, which was less damaged than the Red Town Hall, began to be used for different purposes. Until 1956 it was still an administrative building of the Magistrate of Greater Berlin . This also used a neighboring building on Parochialstrasse , built in the mid-1930s and planned by Kurt Starcks and Franz Arnous as a commercial building for the insurance company Städtische Feuersozietät . The house in Parochialstrasse thus assumed the function of the town house as an extended official seat of various Berlin municipal administrations and thus also the name " New Town House " . The original New Town House , on the other hand, was now called the Old Town House to distinguish it , so that the buildings are repeatedly confused in the literature.

From 1956 until the end of the GDR, the old town house served as the official residence of the first Prime Minister of the GDR Otto Grotewohl and the last Lothar de Maizière . From 1992, two Berlin branch offices of the Bonn federal government were housed here.

A comprehensive renovation began in the mid-1990s and the old town house then served its original use as a building for the city administration, since it has since housed the Berlin Senate Department for the Interior .

history

Search for a "second town hall"

The rapid growth of Berlin since the 1860s by 50,000 people annually also brought about an enormous increase in administrative costs. The capacity of the Red Town Hall, which was only completed in 1869 as Berlin Town Hall, was therefore soon exhausted again, as a comparison shows: when construction began on the Red Town Hall, around 500,000 people lived in the city, and when it was completed, it was already 800,000. As a result, it turned out that the Berlin magistrate would need a second residence, a kind of “second town hall”. An extension to the existing town hall was ruled out by both the municipal authorities and the city council, as an extension of the already structurally closed town hall complex seemed impossible in an architecturally satisfactory way. The construction of the new house was mainly connected with the important questions of how and where .

In 1893 the magistrate proposed a plot of land on the banks of the Spree at the level of the Waisenbrücke ; The Berlin financial administration and the representation of the Social Association of Germany are located at around this point today . The city council rejected the proposed area, however, as they feared that the new building, due to its exposed location, could outperform the existing town hall in terms of effect and shine. Therefore, the question of the new, "second town hall" was postponed for a few years. In the meantime the magistrate approached the MPs again with proposals, but once again neither side found a consensus . In 1898, the then town planning officer Ludwig Hoffmann also intervened in the discussion, who, as Schächse writes, brought about [a] change of opinion among the town councilors through “clever intervention in the debate”. Finally, the Berlin magistrate and the assembly of representatives agreed on the property on Berlin's Molkenmarkt between Jüdenstrasse, Parochialstrasse, Klosterstrasse and Stralauer Strasse. The city gradually bought up the 32 built-up parcels on the planned building site and had the existing buildings demolished.

Through his intervention in the debate, but also through his increased reputation, it was unquestionably clear that Ludwig Hoffmann was to be the architect for the new, representative building. For example, the then town planning officer received the order, without a tender , to design an administration building with around 1,000 workplaces and two meeting rooms. There were no stipulations or even restrictions regarding the design or urban representation.

As he himself reports in his memoir , Hoffmann did not present drafts for the new building until years later. He got two surprises in that he had the exterior design dominated by a tower and the interior by a large hall. The committee members of the city council were initially critical, but in the subsequent vote, the majority voted in favor of Hoffmann's concept. The financial situation of the city of Berlin was so good at that time that even the city treasurer had no objections to the house itself or to the construction of the tower.

Building description

Hoffmann created a monumental building with five inner courtyards “one day to house the offices of the municipal administrations, which have no space in the town hall; But it should also contain the hall for large public celebrations, which the city lacks, and also represent the Berlin of today and thus be a decidedly monumental pompous building ”(Ludwig Hoffmann 1914).

The representative function is shown to the outside in the approximately 80 meter high tower (the information varies here), which rises on a square base above the central projection on Jüdenstrasse. The tower consists of two drums with a column wreath and is crowned by a domed helmet, which carries a 3.25 meter tall Fortuna figure made of copper by Ignatius Taschner . The tower is a quote from the towers designed by Carl von Gontard of the French and German cathedral on Gendarmenmarkt and is intended to show that "Berlin is developing upwards".

Inside, the three-storey, barrel-vaulted ballroom, the so-called Bärensaal , located in the middle of the building, is particularly representative . Georg Wrba designed the Rosso Verona marble floor, six ornate candelabra and three bronze portal grilles that decorate the hall, among other things. The hall itself, which was neither requested by the magistrate nor by the city council, was supposed to be "a town hall for serious celebrations" according to Hoffmann and offers space for around 1,500 people. On the ceiling of the hall, 18 reliefs with “civic virtues” were placed in verse ; in addition, Georg Wrba created a large, bronze bear that was moved to the end of the room. Wrba even made the bear, the symbol of the city, twice: First in a somewhat large shape, which the artist found too depressing in the 19-meter-high hall, so that he - also made of bronze - has a second, reduced-size figure made.

The ground plan of the building follows the dimensions of the demolished city quarter as an irregular trapezoid . The side wings on Parochialstraße and Stralauer Straße cut through the facades on Jüdenstraße and Klosterstraße as three-axis side projections. The main axis with the entrance hall and the ballroom lies between the five-axis central projections on Jüdenstrasse and Klosterstrasse. Cross wings divide the building complex into five inner courtyards.

The facade structure is based on the forms of Palladianism . The two and a half storeys of Tuscan columns and pilasters rises above the rustic plinth with the ground floor and half of the mezzanine . With this blurring of the border, Hoffmann consciously violated the norms of his role model, the Palazzo Thiene in Vicenza . The facade was made of gray shell limestone . The building is crowned by a mansard roof. The front in the direction of Jüdenstrasse is 82.63 meters long, in the direction of Klosterstrasse 126.93 meters, Parochialstrasse 108.31 meters and Stralauer Strasse 94.46 meters.

The town house is rich in sculptural work , including 19 of the original 21 figures as allegories of civic virtues, which were created by the sculptors Josef Rauch , Ignatius Taschner , Georg Wrba and Wilhelm Widemann . In the gable of the front facade there were originally three Berlin city coats of arms from Josef Rauch's workshop. When it was converted into the House of the Council of Ministers , they were removed and replaced by a GDR state coat of arms . After the fall of the Wall, the GDR coat of arms was removed, but the Berlin coat of arms has not yet been reassembled.

Opening after a long wait

The construction work dragged on, so that parts of the administration, including the civil engineering deputation and the city police administration, already moved in in March 1908; Sewer deputation and city fire society followed a few weeks later. The tower itself was built between 1908 and 1911. After more than ten years of planning and construction, Mayor Martin Kirschner opened the building in a festive ceremony on October 29, 1911. The exact construction time was a total of nine years and six months (April 1902 to October 1911).

Ludwig Hoffmann's building was generally considered successful by the population. The “imposing” building placed a focus on the urban environment between Molkenmarkt and Parochialkirche, as did the actual Berlin City Hall, generally known as the Red City Hall , between Alexanderplatz and Nikolaikirche . It was not for nothing that the town house located within walking distance of this was also called the “second town hall”, for which it was predestined with its architecture. From a statistical point of view, the “second” far surpassed the “first town hall”: the town hall offered space for around 1,000 workplaces for civil servants, while the red town hall had just 317. Also in terms of total area, the Hoffmann town hall was around 12,600 square meters as opposed to 9,000 bigger in the old house.

Further events and plans at the time of National Socialism

Nothing significant changed in the townhouse until the 1920s. Neither the First World War nor the subsequent revolution could harm the building. In 1920 the new large municipality of Berlin was formed with the incorporation of many upstream villages and towns such as Spandau , Köpenick , Charlottenburg and Wilmersdorf . This in turn increased the administrative workload considerably, so that some departments and offices had to be outsourced. In 1929, the Berlin magistrate commissioned the building administration to develop a concept for a new administrative building comprising two blocks, which was to simultaneously represent a visual and structural connection between the Berlin town hall and the town hall.

The new administration building should not only create new jobs for civil servants, it should also include the existing main city library and the city savings bank. The construction of the new building was integrated into a large-scale renovation program for the Molkenmarktviertel. Inhumane apartments in the so-called “ Krögel Block” were to be demolished and replaced with new ones. The plans for this program flourished until 1931, but due to the desperate political and economic situation, the implementation could no longer be pursued.

After Hitler took office as Chancellor , the Berlin magistrate and its administration wanted to contribute to the “National Reconstruction Program” - in keeping with the Nazi propaganda - and resumed renovation and new building plans. The plans were particularly good for this program due to the social aspect of the new apartment building in the “Krögel block”.

However, another problem arose: Since the Reich Ministry of Transport ordered the expansion of the Mühlendamm lock in connection with the construction of the Mittelland and Adolf Hitler Canal , the existing Mühlendamm bridge also had to be replaced. As a result, some buildings, including the Ephraim Palace , had to be relocated. A general re-planning of the quarter was welcome, because the Prussian Ministry of Finance also announced the construction of the new Reichsmünze . In the new building with the name "Deutsche Reichsmünze" all existing - at that time six - national coins were to be combined. All of this gave rise to the idea of converting the area around the Molkenmarkt into a kind of “large city and administrative area”, with the town house designed by Ludwig Hoffmann becoming the focus of the new “forum”. Incidentally, the residential construction project of the "Krögel Block" fell out of the plans again.

After the Krögel block with its apartments was demolished in 1936, the new construction of this administrative area could begin. In front of the town house, the new center of the area, a large square was to be created, which was flanked by two identical wing structures on the left and right of the town house. The granite bowl by the stonemason Christian Gottlieb Cantian , which is now in the pleasure garden , was to stand on the square itself, which in turn was to be separated by two large columns, each with an eagle statuette. The new administrative forum also included a so-called “City President's House”, the Reichsmünze and several other administrative buildings. Only a few of these plans were implemented, including the administration building (marked with C and D in the plans) and the house of the fire society, today's “ New Town House ”. In addition to all these urban plans, that is, plans that were actively carried out by the magistrate of the Reich capital, Albert Speer , the general building inspector for the Reich capital , also designed the site of a much larger administrative area for a future " World Capital Germania ".

During the Second World War , the building was hit by aerial bombs , so that there was some damage, especially to wings C and D as well as to the corner of Jüden- / Parochialstraße. The building suffered the greatest damage in the last months and weeks of the war from the approaching front and the so-called "final battle". The mansard roof burned down almost completely, considerable water damage did the rest. In addition, the statues on the entrance risalit on the rear facade to Klosterstrasse were destroyed during the war. The city command gave the damage to about 50 percent.

Situation after 1945

Shortly after the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht on May 8, 1945, the Soviet city commander Nikolai Bersarin was looking for capable, anti-fascist people for a new public administration in Berlin. On May 19, Bersarin appointed the 19 members of the magistrate under the leadership of the acting Lord Mayor Arthur Werner . However, the appointment did not take place either in the Rotes Rathaus or in the Stadthaus, as both buildings were relatively badly damaged. It is reported that the seat of the municipal fire society right next to the town hall had the "best preserved hall in the whole city center". For this reason, too, the magistrate of Greater Berlin , which increased its staff in the next few months, moved into the former building of the fire society in Parochialstrasse 1–3, which was quickly given the name “ Neues Stadthaus ”. In order to distinguish it from the actual town house, the Hoffmannsche Bau was given the name "Old Town House", which is still valid today.

The townhouse, now the “third town hall”, temporarily housed the planning and building construction department, the offices for surveying and housing and a few other offices. While the administrative staff had fully occupied the offices and were using them, the ballroom and the tower rooms were empty due to a lack of heating, high levels of humidity and the resulting mold damage, apart from a few planning exhibitions by the Berlin city planning councilor Hans Scharoun .

From the two buildings of the old and new town hall, the magistrate administered the whole of Greater Berlin until 1948 . After the election to the city council of Greater Berlin in early December 1948, the 14 West Berlin district administrations moved out at the end of 1948. Until the restoration of the Red City Hall in 1956, only the administration for the then eight East Berlin districts worked here.

Changes in the GDR

The damage to the old town house could be reduced to 45 percent by 1950 by a few small construction measures, including an emergency roof covering. The personnel, material and financial resources still existed for smaller jobs, larger construction works could not be tackled in the first post-war years.

The building construction department drew up initial proposals for a reconstruction of the house as early as 1948. Specifically, the main focus was on the roof to be rebuilt. Little by little, two variants emerged: Either a construction of the mansard roof true to the original or the construction of a flat saddle roof . The most important criterion was the required amount of sawn timber , which was neither then nor later in the GDR in sufficient quantities. Therefore, the decision was made in favor of a gable roof with 214 m² of sawn timber, whereas a mansard roof construction would have required 930 m². Monument protection considerations hardly played a role. With both variants it was planned to expand the attic floor for office space.

The reconstruction of the old town house was to take place in five separate phases between 1950 and 1955. The first phase of construction is said to have primarily dealt with the increase in the courtyard wing in the direction of Stralauer Straße (no precise information is available on this). In the second part, the reconstruction work concerned the Stralauer Strasse / Jüdenstrasse wing, with the city council, as the client, having additional offices and a 300-person dining room including a kitchen built in on the fourth floor. These measures were completed by early 1952. For several reasons, however, the subsequent construction phases could not be implemented; Probably the most serious was that the town house was not the official seat of the mayor, and the construction of old, “Wilhelmine” architectural buildings was not a high priority - the construction of living space was much more urgent at the time, so this investment was not included in the national economic plan.

After years of reconstruction, the Red City Hall was completed in 1955 and fully functional again. This enabled many departments of the East Berlin magistrate , which continued to call itself the Magistrate of Greater Berlin , to move from the two townhouses and other more remote administrative buildings back to the Red City Hall.

At the beginning of the same year it became known that the old town house was to be transferred from the now East Berlin magistrate to the GDR Council of Ministers . Since its founding in 1949, this state body had expanded considerably in terms of personnel and needed new rooms, whereby the old town hall was only intended to be an interim solution.

In the fall of 1955, the Prime Minister of the GDR Otto Grotewohl moved into the house. Before that, renovation work took place in order to meet the demands of the Prime Minister and his office management. This included the furnishings in the various ministerial rooms, the previously planned increase of the fourth floor, reorganization of the stairwells, ventilation systems and electrical equipment. Corridors and hallways were given long red carpets; Furthermore, the ballroom was changed considerably in 1960/61, which after the renovation only held 300 instead of 1,500 people. Construction workers also put in new wooden wall panels and a lower false ceiling was hung under the vaulted ceiling. Splendid candelabra , bronze portal bars and the marble floor were also lost. The bear sculpture created by Georg Wrba was placed in the Friedrichsfelde zoo in 1959 .

From 1960 the building became the official seat of the entire Council of Ministers of the GDR . A safety and special zone was set up in the front area, and public access to the “House of the Council of Ministers” was now on Klosterstrasse. The entrance portal to Jüdenstrasse, on which the state coat of arms of the GDR was attached, was only open in exceptional cases.

These changes should also represent the negative attitude towards the “Wilhelmine” character of the town hall, which did not correspond to the ideal socialist image, because, as Schächen writes, Hoffmann's interior design was “pompous, pompous, gloomy and no longer in keeping with the times”. The renovation work cost a total of two million GDR marks .

The Fortuna statue did not survive the construction work either: it was removed during the first reconstruction measures in 1951 and replaced with a 13 meter high radio antenna. After the television tower was put into operation in 1969, it was exchanged for a GDR flag . The Fortuna was stored in the dome until the 1960s , after which it was melted down. The other statues were in the town hall until 1974, after which they were also removed and stored in Friedrichsfelde and other depots, as they had suffered considerable damage from rain and frost.

In general, however, the importance of the town hall in the state apparatus of the GDR decreased. Important events, celebrations and ceremonies took place in the Rotes Rathaus, in the Palace of the Republic or in the State Council building .

The only historical high point was in the late phase of the GDR, when the first and only freely elected GDR government under the leadership of Lothar de Maizière took up office here. So the terms of the Unification Treaty were negotiated in the town hall.

Turning time, complete renovation and new use

- The old town house, photographed between 2005 and 2009

Statue of the goddess Fortuna on the dome

Rear facade in Klosterstrasse

The outer facade is decorated with allegories of the virtues of the citizen

Already in the year of reunification in 1990, the coat of arms of the GDR with a hammer and compass disappeared from the entrance of the building - only a dark stain remained. After reunification, the Berlin branch of the Federal Chancellery and the branch of the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs of the Federal Republic of Germany moved into the building. After a legal dispute, the federal government handed the building back to the State of Berlin as temporary owner in 1993, which wanted to use the house again for its original purpose as an administration building. Before that, however, the town house needed urgent renovation, as statues had been removed and the Bear Hall rebuilt in GDR times, but otherwise little was done to preserve it: some of the sanitary facilities were from the 1920s.

The renovation, which began in 1994 under the direction of Gerhard Spangenberg , aimed to restore the original condition as far as possible, but nevertheless to reveal enough "GDR sins" to point out the acts of the past. First and foremost, the removal of iron girders, cardboard and chipboard was in the foreground. GDR relics worth preserving were either brought to the armory or to the House of History in Bonn. This was followed by the restoration of the original wall paintings and reliefs , which had been whitewashed in the GDR era. At the same time, the outer facade was repaired. In the years 1998/1999, the historic mansard roof was also reconstructed so that it has its original shape again today. The expansion of the fourth floor was left with, but the offices there also received the urgently needed renovation.

The Greek-style statues were restored and distributed to the various locations around the house in December 2005.

The 300 kilogram Fortuna figure, newly made by the restorer Bernd-Michael Helmich, was also placed on the dome on September 2, 2004 using a large crane . Art patron and entrepreneur Peter Dussmann financed the restoration of the figure with 125,000 euros.

However, the renovation also included the construction of the old ballroom, also known as the “Bear Hall”, which was reopened on June 21, 1999. The showpiece of the town house, the bear statue that has now been in the Friedrichsfelde zoo, was brought back to the town house after a complicated transport and "inaugurated" on June 18, 2001. Technical systems were also renovated, including a ventilation system, elevators, lighting and sanitary facilities. The restoration of the old state is largely complete today. It was largely paid for by the federal and state governments. A huge advertising poster for a British cell phone company covered the scaffolding around the tower of the building for a year, thereby helping to fund the project.

Today the Senate Department for the Interior resides in the town house and moved into the building in 1997. The registry office in Mitte was temporarily located here, but it has swapped its seat with the state monument office. In addition, the Office for the Protection of the Constitution of the Interior Administration moved into the building after 2005 .

See also

literature

- Antje Hansen: The old town house in Berlin. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-422-02029-0 .

- Ludwig Hoffmann : New town house, Berlin . In: Neubauten der Stadt Berlin , Vol. 10. Wasmuth, Berlin 1911. (In the online archive of the Architekturmuseum der TU Berlin , contains 50 panels with interior, exterior and detailed views, floor plans and sectional drawings.)

- Heinrich Trost (Red.), Institute for Monument Preservation (Hrsg.): The architectural and art monuments of the GDR. Capital Berlin. Vol. I. Henschelverlag, Berlin 1983, 1990; Beck, Munich 1979, 1983, ISBN 3-362-00497-0

- Wolfgang Schächen (Ed.): The town house. History, existence and change of an architectural monument . Jovis Verlag, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-931321-36-3 .

- F. Schultze: The new town house in Berlin . In: Zeitschrift für Bauwesen , Volume 62 (1912), Col. 1–26, 351–378, Table 1–11. Digitized in the holdings of the Central and State Library Berlin .

Newspaper articles

- Claudia Fuchs: Fortuna's return . In: Berliner Zeitung , August 17, 2002.

- Uwe Aulich: Tower with a new goddess of luck . In: Berliner Zeitung , October 14, 2002.

- Helmut Caspar: New tasks for the old town house . In: Berliner Zeitung , February 21, 1995.

- The giants return to the old town house. In: Berliner Morgenpost , June 12, 2005.

- Rainer L. Hein: Fortuna is returning. In: Berliner Morgenpost , August 31, 2004.

- Hajo Eckert: The renovation of the town house is delayed by months. In: Berliner Morgenpost , February 1, 2004.

- Peter Schubert: Fortuna should bring luck to Stadthaus. In: Berliner Morgenpost , August 20, 2002.

- Hans Hauser: Fortuna on the dome . In: Berlin monthly magazine ( Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein ) . Issue 5, 2000, ISSN 0944-5560 , p. 63-65 ( luise-berlin.de ).

- Kathrin Chod, Herbert Schwenk, Hainer Weisspflug: Old town house . In: Hans-Jürgen Mende , Kurt Wernicke (ed.): Berliner Bezirkslexikon, Mitte . Luisenstadt educational association . tape 1 : A-N . Haude and Spener / Edition Luisenstadt, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-89542-111-1 ( luise-berlin.de - as of October 7, 2009).

Web links

- Entry in the Berlin State Monument List with further information

- Image of the Fortuna figure in the workshop

- Festschrift of the Senate Interior Administration for the reopening of the Bärensaal in June 1999 (PDF; 800 kB) with floor plans and historical pictures

Individual evidence

- ↑ Kathrin Chod, Herbert Schwenk, Hainer Weisspflug: New town house . In: Hans-Jürgen Mende , Kurt Wernicke (ed.): Berliner Bezirkslexikon, Mitte . Luisenstadt educational association . tape 1 : A-N . Haude and Spener / Edition Luisenstadt, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-89542-111-1 ( luise-berlin.de - as of October 7, 2009).

- ↑ berlin.de