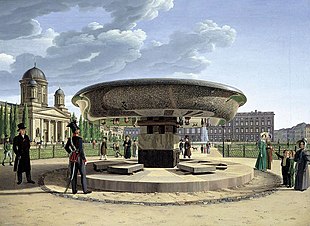

Granite bowl in the pleasure garden

The large granite bowl in the Lustgarten in front of the Altes Museum in Berlin's Lustgarten with a diameter of 6.91 meters and a weight of around 75 tons is also known as the Biedermeier wonder of the world . With a circumference of 69 1 ⁄ 7 feet (about 21.7 meters), it is the largest bowl made from a single stone.

The granite bowl that the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm III. ordered, should first be installed in the rotunda of the museum. Since it was larger than originally planned, it had to be placed in front of the museum. At that time, the bowl was not only a technical marvel that was admired and recognized by the painter Johann Erdmann Hummel in several sketches and paintings, but was also considered a “patriotic symbol”, “cult stone” and “myth”.

history

At the Academy Exhibition in Berlin in 1826, the building inspector and stonemason Christian Gottlieb Cantian showed a circular granite bowl 6 feet (1.83 meters) in diameter and two other smaller bowls made of stone, on which the English ambassador William Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire found favor and prompted him to order such a stone bowl. When the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm III. When he learned this, in 1826 he commissioned Cantian to make such a granite bowl as well. This should surpass the British shell. The king added that "the largest product of the species should remain in the country". Cantian assured the delivery of a 17-foot (5.34-meter) diameter bowl and emphasized that it would be even more impressive than "the magnificent porphyry bowl from Nero's Golden House in the Sala Rotunda of the Vatican". The Prussian regional building officer Karl Friedrich Schinkel then planned to set up this bowl in the rotunda of the Altes Museum, which was under construction, in order to make it “more receptive to enjoyment and knowledge” [sic] of the collection.

Cantian had initially considered a 600-ton granite block at the Neuendorf / Oderberg School Authority to be suitable, but he had already started to split it from 1825. But since the stone had proven to be too brittle, Cantian decided on the Great Margrave Stone , a huge boulder weighing an estimated 700–750 tons and an age of 1420 million years. These existing red Karlshamn granite boulder had the Saale or Weichseleiszeit from Karlshamn in the central southern Sweden up to the Sandberg in Rauen's mountains transported, where a number of other large stones is located.

The blank for the granite bowl was split off from the larger of the two margrave stones in September 1827. After a successful split, Cantian informed the king that, according to initial investigations, a size of the bowl of 22 feet (6.90 meters) was possible, and that he should order how to proceed. The king ordered the height of 22 feet. The bowl of this size no longer fit into the rotunda and put Schinkel in a difficult situation, because on the one hand the bowl should form the center of the rotunda, on the other hand the room aesthetics could be negatively affected by such a large bowl. Schinkel therefore suggested that the bowl be placed in a semicircle in front of the open staircase of the museum and presented the king with drawings of the rotunda with the different sized bowls so that he could make a decision. After several lectures, Schinkel was able to convince the king and he finally approved the installation in the open on February 21, 1829.

Granite as a patriotic symbol, cult rock and myth

With the formation of the nation states in the pre- and post-Napoleonic times, rulers developed publicly visible symbols of power, influence and size. In accordance with this way of thinking, old monuments were dismantled in Egypt and other ancient regions and erected in European metropolises, and if one didn't get anything from them or wanted more, new objects were created; also the Berlin bowl. Sibylle Einholz , who received the order in 1997 to clarify the ownership of the granite bowl, puts the Biedermeier wonder of the world in a more comprehensive context. The previous view of the large granite bowl as a Biedermeier wonder of the world, as a technical marvel of the processing and transport of the bowl by Cantian and its artistic appreciation by the painter Hummel is insufficient. She also evaluates granite as a bearer of meaning in the Biedermeier period , as a "fatherland symbol", "cult stone and myth ". Furthermore, the location of the shell is of particular importance.

Patriotic symbol

In addition to the fascination of the external appearance of granite in its different colors and shiny reflections, human properties were assigned to this rock in the Biedermeier period, says Einholz. Granite was difficult to work with with the methods and tools customary at the time, and to bring it to a polish. Granite was a symbol of strength and steadfastness. This thesis is proven by the fact that Friedrich Wilhelm III. on September 1, 1818, when the decision was made on the design of the Luther monument in Wittenberg, he insisted on a granite base, because only this material would equal Luther's character of unshakable strength.

She points out that granite boulders were not only endowed with human characteristics, but also given the attribute "patriotic". In 1818 Johann Gottfried Schadow wrote to Goethe about the planned Blücher monument in Rostock that "the pedestal of nine feet (2.82 meters) made of native granite" could only be made in Mecklenburg granite for him. Goethe saw his old thesis confirmed in his essay “Granite Work in Berlin” (1828) that the huge boulders did not come from afar, but “they remained in place, as remains of large masses of rock that had crumbled into itself ". Cantian himself presented his work in the academy's exhibition catalogs as being made of “patriotic granite”. The motto or the “national index” was the “largest bowl from the largest granite find”, according to Einholz. Comparable monumentalism failed at the planned Blücher mausoleum, which was to be covered by a dome with a diameter of 4.25 meters based on the model of the Theodoric's tomb in Ravenna made from a granite boulder called "Blücherstein" from the Silesian Zobtenberg . That failed entirely because the 650-ton granite block could not be transported due to technical difficulties.

The granite boulders that can be found regionally were elevated to national symbols in the Biedermeier period. The transfiguration of the granite was shown, among other things, by the fact that the King of Prussia bought granite without specifying a purpose. All parts of the Margrave Stone found prominent uses.

Cult rock, myth and place of installation

For Einholz, the reason why granite was stylized as a “cult stone” at the beginning of the 19th century is that there was a noticeable ambivalence to traditional cults in the Biedermeier period. The two porphyry tubs from the ruins of the Diocletian Baths , which Wilhelm von Humboldt had acquired for the museum in Rome in 1810 , were intended to serve as sarcophagi for the royal family. The connection to the burial traditions of Roman antiquity and the Florentine Medici was intended. This thesis is confirmed elsewhere:

“Both the stone porphyry and the color purple were relatively rare and thus already reserved for the emperors by the Romans (for example for sarcophagi made of porphyry). This tradition has been inherited in many later cultures, e.g. B. Byzantium , German Empire under the Hohenstaufen , z. B. Bishops of chr. Church and, perhaps last, with the Medici in Florence . "

Furthermore, granite and porphyry have an identical mineral composition and are both reddish in color. The parallels are obvious, and the Cantian porphyry bowl was also known, which, as is well known, wanted to make an even more “wonderful” one.

In addition, the "Holy Mountain of Silesia", the Zobtenberg , was proposed as the site of the Blücher monument, on which Celtic and Germanic places of worship had been located since the 5th century. Schadow had made a design for this that could not be realized. Einholz derives from Goethe's writing on granite from 1828,

“That the granite is to be understood as a nucleus, as a carrier of original information about the design rules of the earth. The poet speaks of the dignity of the rock, which is not only the foundation of our planet, but also the highest and the lowest. The noble stone - gemstone - is only suitable for processing into an exquisite solitaire. "

Initially, it was planned to set up the bowl at the most exposed point within the museum and the change directly in front of the entrance to the museum suggests that there is a deep connection to this place. The shell is not only part of the museum's architecture, it also transfers content. Goethe interprets Einholz as

"That in another place he understood the museum as a kind of new sanctuary to which people go on pilgrimage like a pilgrim, we have to attribute a special aura to the exhibited objects."

In addition, she sees a timely connection:

"The cycle of pictures planned in the entrance hall, literature on the development of life on earth [...] would correspond to the basic idea, set in a granite solitaire, about the shape of the earth as a geological quintessence - whether in the rotunda or in front of the outside staircase, remains the same."

Manufacture of the granite bowl

The processing of the blank, the transport and the grinding in Berlin were followed with great interest by the public. The painter Johann Erdmann Hummel , who created several oil paintings and sketches, was commissioned with the documentation . Some have been preserved, a picture of the turning of the half-finished bowl in Berlin burned in the Märkisches Museum during World War II . Hummel was not interested in the symbolism of the bowl. In addition to the precision of the painted picture in the representation of the perspective and the reflections on the underside of the bowl, it is noteworthy that Cantian, the man with the top hat, and Hummel's sons and their cousins are in the picture.

Stone cleavage

Work on the bowl began in May 1827. 20 stonemasons were employed every working day. One or two blacksmiths were employed on the margrave stones with shapes and hardening of the stone cutting tools.

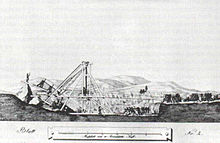

First of all, the Große Markgrafenstein weighing around 700 to 750 tons (dimensions: length 7.8 m, width 7.5 m, height 7.5 m) was turned by around 90 degrees for the first time by the middle of June using ten winches (Fig. : from S to N). This process was the prerequisite for splitting off a correspondingly large piece of stone on August 24, 1827 by using 95 iron wedges .

The first split did not work optimally and larger protruding stones had to be laboriously removed with hand tools. The second split at the beginning of November was also not optimal. Once again, additional stone protruding had to be removed by wedging large pieces of stone and using stonemasonry with a hammer and chisel. It took until December 23, 1827 to turn the 5 foot (1.57 meters) thick stone slab (Fig .: bd-ac) to work on the underside of the shell (Fig .: ba downwards). After completing the underside, the 225-ton slab had to be turned again with 23 hoists and with the help of 100 employees. This operation was completed on April 26, 1828; then the shell was hollowed out by August 4th.

Transport and finishing

The production of the profiled shell outside and further work on the shell, as well as special transport preparations, for example the construction of a wooden beam frame, were completed in mid-September 1828. During the work, 44 workers could find space for breakfast on the edge of the bowl.

The bowl, which at that time weighed between 70 and 75 tons, was transported to the Spree with the help of wooden rollers . A plank railway and a road through the forest to the Spree were laid; the route can still be seen today (as of 2008). The transport took six weeks; Daily progress was 600 feet (188 m). 54 people were needed to load the shell onto a wooden ship specially stiffened for this purpose.

When it was completely polished, the shell would have had to be secured against scratches and other damage during the long transport route with great effort. That is why it was initially only finished according to its external shape and transported with a rough surface. On the way to Berlin, the Grünstraßenbrücke had to be severely demolished.

The bowl reached Berlin on November 6, 1828. Not far from the site at the Altes Museum, it was brought to a specially constructed building at the Packhof. Inside was a steam engine with ten horsepower (HP), with the help of which the shell was rounded and smoothed to a high gloss in two and a half years of grinding and polishing processes.

It was the first time in Germany that such hard rock was polished with the help of a machine, with the polishing of curves and cavities being an additional difficulty.

During grinding, it turned out that the shell had three cracks. These cracks were either of natural origin or formed when splitting in the Rauenschen Mountains. Well-known naturalists of the time, such as von Klöden and Wöhler, examined the bowl in 1831, and at Cantian's insistence it was placed under a protective roof in winter. Presumably one of these cracks, which were deepened by the effects of frost over time, caused the shell to break in 1981.

Lineup

The museum opened in 1830. Cantian wanted to put the bowl on high pillars. Schinkel contradicted this, who wanted to set up the bowl close to the floor in front of the museum stairs on simple granite plinths. The king granted Schinkel's request. The free installation on three bases made it possible to see inside the bowl. The bowl was initially set up temporarily on November 14, 1831 and officially handed over to the Royal Museum on November 10, 1834. The price for the bowl was estimated at 12,000 thalers and was ultimately 33,386 thalers. This sum was only officially approved after a revision.

Lithograph of the Great Margrave Stone by Julius Schoppe , as it was still to be seen at Pentecost 1827 (Cantian at the bottom right with cylinder).

State and naming

Since the bowl could not be set up at its originally planned location in the rotunda within the Altes Museum due to its size , it was on the one hand exposed to weathering and on the other hand was also affected because this place was also the site of numerous rallies in the Weimar Republic and there was marches. The shell was stepped on as a viewing platform and the surface was scratched. In 1934 the bowl was moved north of the cathedral because it was in the way of the Nazis for their marches and they paved the square. During the Second World War it was damaged by shell hits, and after the war the pleasure garden was part of the newly created Marx-Engels-Platz. It was stored between the barracks of the Berlin Dombauhütte until it was put back in its previous location in 1981 on the occasion of Schinkel's 200th birthday. It had a crack that was cemented and is now clearly visible. A larger defect on the edge of the bowl, which was caused by the war, was repaired with a so-called crossing made of red granite (see pictures). On the occasion of the redesign of the pleasure garden from 1997 to 1999, the base made of gray Lusatian granite was replaced by the reddish French granite Rose de Clarité .

After around 190 years in the open, the shell's polish has suffered. The oil painting of the finished bowl by Johann Erdmann Hummel from 1831 shows the originally mirror-smooth surface. The shell is now a listed building .

The Berliners nicknamed the bowl “soup bowl”. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe mentioned the polishing of granite, admired the granite bowl measuring 22 feet (6.9 meters) and called it "granite basin".

- Repair of damage to the granite bowl

Replacement piece ( crossing ), a repaired war damage

Rock material used

The granite bowl and the three bowl bases are made of southern Swedish Karlshamn granite ( Precambrian ); the base frame made of French Rose de la Clarté granite ( carbon ). The pavement surrounding the shell consists of Oberdorlaer Muschelkalk ( Triassic ) from the town of Oberdorla in Thuringia and of Chinese greywacke .

More large stone bowls

The Berlin bowl in the Lustgarten is by no means a solitaire from that time.

- In the Hermitage in Saint Petersburg, an oval bowl made of Revnev jasper , measuring 5.04 mx 3.22 m, rests on a base about two meters high. The production of the jasper bowl lasted from 1820 to 1843. What is remarkable about this bowl is that it was made from the world's largest piece of jasper, a gemstone from which other jewelry items are made. The circumference of the bowl is 12.55 meters (just under 40 feet ).

- The one-piece porphyry bowl in the Vatican Museum , probably from Nero's Golden House , is 13.97 meters (44.5 feet) around a third smaller than the granite bowl in Berlin's Lustgarten.

See also

literature

- Sybille Einholz: The large granite bowl in the pleasure garden. On the importance of a Berlin solitaire. In: The Bear of Berlin. Yearbook of the History Association for Berlin 46, 1997, pp. 41–62.

- Dominik Bartmann , Peter Krieger, Elke Ostländer: Gallery of Romanticism . Ed .: National Gallery Berlin State Museums Prussian Cultural Heritage. Nicolai Verlag, Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-87584-188-3 , p. 148-150 .

- Ludwig Scherhag: The stonemason and his material. Natural stone work in Germany. Example Berlin . Exhibition catalog. Ed .: Federal Association of German Stonemasons, Stone and Wood Carving Crafts. Ebner, Ulm 1978.

- Ludwig Friedrich Wolfram: Doctrine of the building materials. First division. From the natural building blocks . In: Complete textbook of all architecture . Hoffmann, Stuttgart / Vienna (1833–1835).

Web links

- Entry in the Berlin State Monument List

- Illustration of the turning of the bowl ( Memento from December 16, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- Figure of Karlshamn granite

- The margrave stones on literaturport.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ History of the Berlin Lustgarten. DHM

- ↑ Volker Koop: Not a fight for Berlin? In: Berlin monthly magazine ( Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein ) . Issue 11, 1998, ISSN 0944-5560 , p. 109–115, here p. 115 ( luise-berlin.de ).

- ^ Berlin 1237 ( Memento of February 7, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ However, it is not known whether Cantian carried out the Englishman's order and whether an additional bowl was made.

- ↑ a b Einholz 1997, p. 41.

- ↑ Acta Go. Prussia. State Archives No. 20471, pag. 1. Quotation from Einholz 1997, p. 41.

- ↑ Schinkel's confirmation on November 25, 1826; he also suggested placing the bowl on bronze lions in the center of the room. Quoted from Einholz 1997, p. 58, note 5.

- ↑ Michael Niedermeier : Goethe and the stony path of scientific knowledge. In: Counterwords. Journal for the dispute about knowledge. Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences, Volume 9, Spring 2002, p. 84.

- ↑ “Schuddebeurs & Zwenger (1992) identified the rock as Karlshamn granite. This comes from central southern Sweden and is around 1240 million years old. Its purpose has meanwhile been confirmed several times. "Quoted from Ferdinand Damaschun, Uwe Jekosch, J. H. Schroeder: The large granite bowl in the pleasure garden . S. 119, Guide to the Geology of Berlin and Brandenburg, No. 6., ed. v. J. H. Schroeder, self-published geoscientists in Berlin and Brandenburg e. V., Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-928651-12-9 .

- ↑ Acta No. 20471, pag. 46. Quotation from Einholz 1997, p. 58, note 6.

- ↑ Schinkel's drawing in Acta No. 20471, pag, 13 of September 4, 1827. Quoted in Einholz 1997, p. 58, note 7.

- ↑ Einholz 1997, p. 43.

- ↑ a b Einholz 1997, p. 52.

- ↑ cit. based on: Niedermeier 2002, p. 82.

- ↑ Einholz 1997, p. 59, notes 21 and 22.

- ↑ Einholz 1997, p. 59, note 22.

- ↑ Acta No. 20471, pag. 145. Quoted from Einholz 1997, p. 59, note 23.

- ↑ Dietmar Reinsch: Natural stone studies. An introduction for civil engineers, architects, preservationists and stonemasons. Enke, Stuttgart 1991, ISBN 3-432-99461-3 , p. 124.

- ↑ Einholz 1997, p. 53.

- ↑ Einholz 1997, p. 55.

- ↑ Einholz 1997, p. 56.

- ↑ Comparison of the mirror gloss of a granite bowl in Berlin and a porphyry bowl in Rome ( Memento of the original from December 29, 2009 in the Internet Archive ; PDF; 1.3 MB) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Einholz 1997, p. 51.

- ^ Exhibition catalog History in Stein , pp. 57–58.

- ↑ Einholz 1997, pp. 45-46.

- ↑ Acta No. 20471, pag. 126. Quoted from Einholz 1997, p. 59, note 17.

- ↑ Einholz 1997, p. 41.

- ↑ Damaschun et al. : Large granite bowl. P. 119

- ↑ Entry in the Berlin State Monument List

- ^ Johann Wolfgang von Goethe : About art and antiquity . Sixth volume, second issue. Cotta, Stuttgart 1828.

Coordinates: 52 ° 31 '8.78 " N , 13 ° 23' 56.99" E